Chapter 18

Milne Bay

‘If you were going to give the world an enema—you’d push it in at Milne Bay’

—Pilot Officer B.E. ‘Buster’ Brown

‘Of all the allies, it was the Australians who first broke the invincibility of the Japanese army’

—Field Marshal Sir William Slim, Defeat Into Victory

There is a quiet sort of Australian man who, in obscurity, achieves great things for which a few people are eternally grateful; he then fades away unsung and is soon forgotten.You can see him on weekends tinkering in his shed, or sanding a little boat, or pursuing an odd hobby. He does his duty, fails with dignity and, when he succeeds, succeeds without trumpeting his success. He is remote, and self-absorbed, and is liked by his grandchildren. His life is one of ceaseless curiosity within his chosen field, of which he is a supreme expert. He is scarcely comprehensible to women—one of whom, tolerating his self-absorption, rewards his devotion and loyalty with her unstinting love.

‘Silent’ Cyril Clowes, the Australian commander at Milne Bay, seems to have been such a man. No biography exists of this extraordinary commander; few Australians will have heard of him. After Duntroon Military College, where his classmates were Rowell and Brigadier George Wootten, he pursued a long and successful career as a professional soldier and rose to the rank of major-general. He won a swag of medals and decorations (CBE, DSO and MC) in both world wars, and earned the reputation of being oblivious to personal danger.

A brilliant artilleryman—some say the finest the Australian army has produced—Clowes was a decisive, steadfast, pipe-smoking general with a conspicuous personal trait: he rarely spoke. Even his best friends called him Silent Cyril. ‘He was a very good commander in my book,’ observed Colonel Fred Chilton, his staff officer, ‘but he wasn’t a good communicator.’

Yet Clowes’s friends saw the value of this honest soldier in a world of incipient spin: ‘The only thing I think he can be criticised for,’ added Chilton, ‘is his lack of public relations—for not sending back phoney reports about what a wonderful job he was doing and how many Japs they’d killed…he didn’t give the boys [in GHQ] what they wanted…’1

Clowes quietly led the first land defeat of the Japanese, in any war. He deployed 4000 infantry troops, two squadrons of Kittyhawks and few words against 2400 Japanese naval commandos armed with tanks.2

The Battle of Milne Bay was a complete Australian victory. This statement is not intended to be crudely triumphalist; it is meant simply to distinguish the battle from MacArthur’s boast of another ‘Allied’ triumph on this semi-elliptical bay at the eastern tip of Papua. Undeniably the Americans offered logistical and engineering troops (fourteen of whom were killed). But the infantry blood spilt at Milne Bay—as in the Owen Stanleys—was Australian.

The victory came at a critical moment: just after the battle of Isurava, from which Potts had been forced to withdraw. The effect on morale was incalculable: Milne Bay is said to have broken the spell of Japanese invincibility, no less. It is not churlish to point out, however, that the Japanese were outnumbered two to one and lacked airpower; yet they did have tanks.Australia’s 75 and 76 Squadrons were crucial to this victory: early in the battle their pilots did irreparable damage to the Japanese supply lines. Even so, the infantry largely won land wars in those days, and the Australian infantryman at Milne Bay fought with phenomenal courage.

A lesser-known fact about Milne Bay is the unspeakable cruelty the Japanese unleashed against the native people and Australian prisoners, as later documented by the Webb Report on Japanese war crimes.

Both sides saw this vile waterway at the eastern end of the New Guinea mainland as strategically crucial. Blamey and MacArthur were determined to hold Milne Bay. Not for nothing had the Allies built two narrow, steel-matted runways here. The Japanese similarly valued it as a crucial air base, from which their Zeros could fan out over northern Australia, encircle Port Moresby and link up with the Nankai Shitai, which were then fighting in the Owen Stanleys.

From a distance it seemed like paradise. Up close, in 1942, Milne Bay was a disease-ridden basket case of interminable rain and steaming heat, and the most malarial region on earth. All the troops caught malaria or dysentery or both.

The bay is a natural deepwater harbour. The entrance is seven miles wide, and the depth westwards, about twenty miles. Steep, jungle-covered mountains rise to 3500 feet on three sides, leaving only a narrow strip of mangrove swamps, coconut groves and boggy tracks to which the few human inhabitants clung.

The mountains drew 200 inches of rain a year, which splashed down the sides and drenched the coastal villages. The Australians complained endlessly of their discomfort. One wrote:‘Even without the war Milne Bay would have been a hell hole…The sun hardly ever shined and it rained all the time. It was stinking hot and…very marshy, boggy country…It was a disease-ridden place—it was terrible.’ Not only that, coconuts tended to fall on them from high palms; the men were told to wear steel helmets in the plantations after one coconut broke an officer’s collarbone.

Allied intelligence was vital. FRUMEL decoders in Melbourne intercepted Japanese signals3 that detailed the enemy’s invasion plan, in response to which MacArthur and Blamey sent up the 18th Brigade to hold the bay. Militia units had garrisoned Milne Bay since early August; on the 21st, the last of the AIF reinforcements landed there aboard little fishing luggers—Milne Bay had no wharf.They negotiated the reefs in tiny dinghies, one of which sank under the weight, and a soldier drowned. Ashore, the men drew lots for the best tents; these were of little use. On the first night, six to eight inches of rain fell.

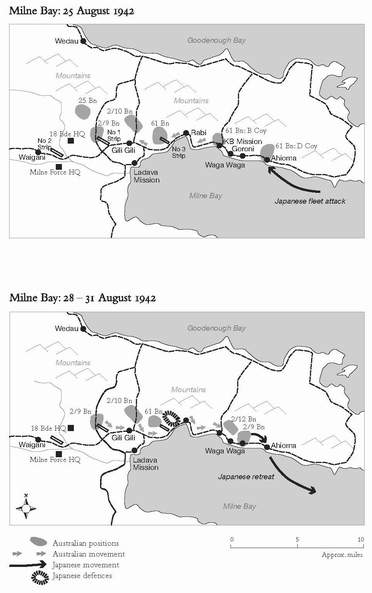

Clowes established his HQ near the village of Gili Gili, on the northwestern corner of the bay where the coastal plain is widest (facilitating the construction of the two airstrips). From here a twelve-foot wide, mud-gorged track—previously covered in soft coral and contemptuously described as a road—ran several miles along the north shore through creeks and swamp. It linked the settlements of Rabi and KB Mission to Ahioma, where the Japanese landed.

They landed by moonlight on 25 and 26 August. Their orders, from Rear Admiral Matsuyama, were uncompromising. They must ‘strike the white soldiers without remorse. Unitedly smash to pieces the enemy lines and take the aerodrome by storm’.4

Some 2400 Japanese leapt ashore and ran up the beach into the shelter of jungle. Most were commando-style troops of the notorious special naval landing parties—but not all. Sakaki Minoru, First Class Seaman of the Kure 5 Special Naval Landing Party, had no jungle training and scarcely any rifle practice. He carried two days’ rations, of biscuits and ‘bento’.5 A bank clerk in civilian life, married with two sons, then aged four and five, he seemed thoroughly disinterested in the whole exercise.

Most showed greater determination than Sakaki. The navy, arch rivals of the army, needed to redeem their failure to capture Port Moresby at the Battle of the Coral Sea. Milne Bay afforded them that chance. ‘Milne Bay would make a good jumping-off point for an attack along the south coast,’ according to war historian Peter Londey.6

The stakes were extremely high. By landing at Milne Bay, the Japanese hoped to open a second front in their attack on Port Moresby. Already they had met severe setbacks: 350 Japanese troops died when Australian Kittyhawks strafed their landing barges at Goodenough Island.And on two mornings after they disembarked at Milne Bay, Australian pilots destroyed their barges and most of their supplies. Instead of moving down the shoreline by barge—as they’d planned—they were forced to march along the swampy coastal strip.

Clowes did not know how many Japanese had landed on those gloomy tropical shores; his staff estimated 5000. In fact, the enemy numbered half that. For their part, the Japanese fatally underestimated the size of the Australian garrison. And yet, Keith Hinchcliffe, part of an Australian radar unit, was not alone in feeling premonitions of doom the night the Japanese convoy entered Milne Bay: ‘…there was no future for us at Milne Bay. Singapore had fallen. The Japs had landed at Buna and occupied Gona and Lae and were fighting their way towards Moresby…We had our bags packed and were anticipating a walk…along the coast to Port Moresby. Our mood changed within 36 hours…’7

Though outnumbered, the Japanese had one advantage: tanks. Their tanks were light, high-turreted machines vaguely reminiscent of a Dalek, the tottering robots from Dr Who. At night on the 27th several Daleks—the spearhead of clusters of creeping troops—trundled along the coast over streams and through deep mud towards the Australian lines.

Clowes had sent one AIF battalion8 into the coconut plantation at KB Mission, a tiny settlement halfway along the north shore. The first tank advanced with its dazzling headlights shining through the pouring rain, at which one Australian soldier shouted, ‘Put out that fucking light!’9 Alas, it was not an Australian torch.

Then, from behind the tanks, came an extraordinary sound: the choir-like note of a single voice—‘and a beautiful voice it was’—in Japanese. Hundreds of others soon joined in, singing ‘in sonorous unison’.10 The war chant rose to a crescendo, and then the Japanese charged. The tanks drove straight into the Australian lines, floodlighting each other’s sides for protection from grenade runners. ‘The enemy tanks were fitted with brilliant headlights, with the aid of which they cruised around amongst our troops inflicting many casualties,’ wrote Clowes.11

Bayonets flashed, and dreadful screams could be heard in the darkness. The adrenalin of hand-to-hand combat shut out the peripheral noise in the troops’ ears. One group of grappling bodies spilled into the sea, so narrow was the battlefield. The tanks charged into small parties of troops, trying to flatten them. The Australians leapt out of the way and hurled ‘sticky bombs’—anti-tank grenades packed with nitroglycerine. Most bombs rolled off or, damaged by damp, failed to explode. ‘From close range they threw them but they did not stick,’ wrote Frank Allchin, a battalion commander.12

The Japanese forced the Australians back beyond Gama River, where militia units13 held the line—a rare instance of the militia covering the withdrawal of the AIF.

GHQ peered into the glass darkly. Blamey and MacArthur couldn’t abide a Japanese presence on the eastern Papuan seaboard, and pressed Clowes to clear the enemy from Milne Bay immediately.

Urgent cables tapped back and forth between Clowes’s tent, Port Moresby and Brisbane. GHQ demanded news from Silent Cyril, whose silence, at this time, was due rather to the genuine dearth of information on Japanese strength than to his natural reticence. Clowes’s apparent lack of offensive activity agitated MacArthur extremely. Nor were the Americans pleased with Clowes’s laconic sitreps, which lacked the tendentious verbosity of their own battle reports written in what George Vasey smilingly called ‘Americanese’.

Vasey—then Deputy Chief of the General Staff—meanwhile warned his friend Rowell of the ‘wrong impression’ the troops at Milne Bay were creating ‘in the minds of the great’. In fact, Milne Bay exposed gathering fault lines in the minds of the great, which was epitomised by Vasey’s arch question: who, he breezily wondered, in a private letter to Rowell, was commanding the Australian army—MacArthur or TAB (Blamey)?14

For three days sporadic skirmishes—a neat military euphemism for bloody lunges by hate-filled enemies staggering through mud in pouring rain—seemed to confirm MacArthur’s poor opinion of the Australian troops. He felt he must explain the causes of the delay to Washington, in case of doubt about who was responsible. He alerted Roosevelt, ‘I…am not yet convinced of the efficiency of the Australians.’15

Vasey anxiously awaited good news. As the first to see Clowes’s sitreps cabled in morse to Brisbane,Vasey longed for a breakthrough to throw in MacArthur’s face. He told Clowes:‘I’m dying to go back to those bastards [at GHQ] and say “I told you so—we’ve killed the bloody lot.”’16

Slowly,Vasey’s wishes materialised. On 29 August Clowes sent in two battalions of the 18th Brigade—the crack formation that would inflict such misery on the Japanese at Buna. By day, Australian pilots strafed Japanese positions on the north shore, as the infantry gradually forced the Japanese back over their occupied ground towards KB Mission.

The gruff, thickset Brigadier George Wootten—soon to lead his men with awesome finality at the battle of the beaches—sent up reinforcements. Bit by bit the Australians clawed their way along the muddy track. They inflicted hundreds of Japanese casualties. At the night battle of Gama River, a Japanese unit came jogging along the track straight into Australian machine-gunners, who were alerted by a lookout perched in a coconut tree. Within minutes, 92 Japanese were killed and hundreds wounded.Aerial bombardment meanwhile cratered the shoreline in readiness for the final clearance.

At this moment, Clowes received an oddly peremptory message. It was 7.00 p.m. on 1 September, and he was preparing for a final thrust (in battle, it seems, the next thrust is usually final). Instead, GHQ warned: ‘Expect attack JAP ground forces on Milne aerodromes from West and North-west, supported by destroyer fire. Take immediate stations. MACARTHUR.’

This intelligence had the smack of Ultra-decoded authenticity; it wanted to be taken seriously. So Clowes put his eastern offensive on hold.All that night the Australians kept watch for an attack from the most unlikely direction, over the mountains behind them. Nothing happened. The intelligence was baseless, and the delay, immensely frustrating. Clowes questioned whether MacArthur’s decoders had translated accurately. Later he wrote that these ‘decodes of “most secret” Jap signals were of little use to us and served merely to hinder and hamper the development of our counter-attack…’17At dawn the men resumed the grinding battle eastwards, along the north shore.

Hideous, flyblown atrocities formed before their astonished eyes. In the villages and along the track appeared the first signs of the enemy’s gruesome handiwork. One Australian captain found the body of a native boy, bound with wire, a bayonet up his anus and half his head burnt off with a flamethrower; nearby a native woman lay bound by her hands and legs, with her left breast cut off. Both victims, mercifully, were dead. Nor did the Japanese spare two Australian militia troops, on whom they had practised bayonet attacks; one, tied to a tree, had deep bayonet wounds in both arms, and a bayonet jutting from his stomach. They were the first in a revolting catalogue of Milne Bay war crimes.

Revulsion turned to anger; anger to cold fury. News of the atrocities put the Australians in a mood of murderous rage. No prisoners would be taken. A measure of this attitude were the bullet wounds found in the body of a Japanese sniper, dangling from a tree: every time an Australian platoon came up the track and saw the hanging corpse, they riddled it; 500 bullet holes were later found in the body.

In coming attacks, dozens of men on both sides died fighting in conditions of ghastly proximity. On one especially dark night, Sergeant Jim Hosier, on a mine-laying patrol, felt a Japanese hand run over his face.

The Australian 18th Brigade soon recaptured KB Mission. They walked through clearings strewn with Japanese bodies. One sergeant, concerned about fakers, told his platoon, ‘Look—I want you all to make sure these Japs are dead. As you go through, stick them.’ A rather quiet, introspective soldier refused. He was told, ‘It’s for all our safety’—and he was reminded of an incident when an apparently dead Japanese had shot a passing Australian. The quiet soldier said ‘Okay’, and lunged his bayonet into the nearest Japanese body, which groaned and crawled forward. The Japanese had been hiding his rifle. The Australian shook with revulsion and never quite recovered from the incident. He died later in the campaign.18

In the jungle nearby the Australians found the burnt-out shell of a Kittyhawk and the body of the legendary pilot, Squadron Leader Peter Turnbull, who had flown dozens of air raids against Japanese positions. The sight brought home to the infantry the reality of the air battle. Their reliance on air power at Milne Bay cannot be overstated, as Blamey said.*

The man largely responsible for the air victory was Group Captain William Henry Garing, the RAAF’s commander at Milne Bay. He had won the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in Europe, for engaging five German bombers. Garing was a brave and forceful officer, whose nickname ‘Bull’ accurately described his personality. The historian Dr Alan Stephens praised Garing’s ‘expert planning and inspirational leadership at Milne Bay and the Bismarck Sea’.19

Into the melee beyond KB Mission crept ten Australian troops led by ‘the quietest and most unassuming man you could ever see’,20 an apprentice hairdresser from Crows Nest, Queensland, named John French. On 4 September, this 27-year-old veteran of the Siege of Tobruk stopped his men short of three enemy machine-guns. If they rushed in together they would surely all die. So, ‘as their leader’, French decided, ‘it was his duty to attack on his own’.21

French ordered his men to take cover, then advanced on one of the machine-guns and silenced it with grenades. He then killed the second machine-gunner with his Tommy gun. Badly wounded, he stumbled forward and fell in front of the third gun pit; later all three enemy gun crews were found dead.

French saved the lives of his section, cleared the path for the Australian advance, and won a posthumous Victoria Cross, the second on Australian territory. He and Private Bruce Kingsbury are buried at Bomana Cemetery in Port Moresby.

The terrain did the job the sticky bombs couldn’t: tanks got bogged in deep, treacly mud and torrential rain, or ran off the road, where they were easier prey to Australian firepower.

The cooperation between the Australian army and the air force delivered the coup de grâce at Milne Bay. ‘Australian fighters forced the Japanese to move entirely at night.’22 Kittyhawk pilots strafed any visible Japanese activity: ‘Palm fronds, bullets and dead Japanese snipers were pouring down with the rain,’ one witness remarked.23

The wounded died where they fell, or dragged themselves back to the beachhead, half a mile to the east.Another Japanese convoy sailed into Milne Bay on the night of 6 September to evacuate the troops—some 1400 of them escaped. The fleet bombed and sank the Anshun, an Allied supply ship and twice bathed another Allied vessel, the hospital ship Manunda, in searchlight, and spared it—a rare example of restraint.

Many Japanese troops fled into the mountains, doomed to long excursions through the bush before starvation, disease or Australian patrols claimed them. An anonymous Japanese diary, captured at Milne Bay, tells of one soldier’s end: ‘Hid and lived on the ground for about 25 days. Ate coconuts, papayas, apples and mountain potatoes…Even though I am lost I cannot give myself up…it is hard to believe I am still alive…’

The diarist escaped a machine-gun attack, but wrote that he had lost ‘my helmet, canteen and my mess gear’. ‘In case I am killed please forward my pass-book number to [a Japan address].’ His last entry was: ‘Received a bullet in my back. Have live ammunition in my back…’24

The aftermath of Milne Bay brought home the extremity of the Pacific War. Japanese ground troops left a trail of cruelty, ‘such as to shock and dismay the feelings of every decent human being’, observed Evatt, Australia’s wartime Minister for External Affairs.25 Of the 95 atrocities documented by the Webb Royal Commission on war crimes, 59 were perpetrated against native people and 36 against Australian troops. Justice Webb conceded that, in a few instances, the same case may have been described several times. That did not diminish the horror. To say the Japanese flouted The Hague Convention at Milne Bay is a cruel understatement. The prolonged torture and apparent pleasure with which they dispatched their victims suggests the Australians were fighting, not soldiers, but a criminally insane mob of serial murderers and rapists. The Japanese at Milne Bay demonstrated none of the restraint of trained professional soldiers, but rather the barbarity of rampant Visigoths.

Cynics and pacifists may scorn the notion of ‘civilised war’ implicit in the rules of war drawn up at The Hague. Indeed, the cumulative horror of the twentieth century consigned the notion of a ‘gentleman’s war’ to its deserved dustbin. But there are clearly boundaries. If not, who were the rules devised at The Hague aimed at? The atrocities at Milne Bay help to answer this question, which is the only case for describing them here.

The Japanese bound and bayoneted dozens of tribesmen who refused to cooperate with them.Women were raped, sometimes with bayonets. One native woman was pegged down and slit from her throat to her vagina; a teenage girl was nailed to the ground with a bamboo stake through her chest. The genitals and anuses of several native men and women were mutilated; the breasts of several women were chopped off and left on or beside their bodies. One woman was disembowelled, and one man’s buttocks were hacked off. At Moteo the Japanese tied a man’s hands with signal wire and shot and bayoneted him several times.At Wanadela, three young women were bound, raped and mutilated. Near Waga Waga, two hundred yards from where the Japanese landed, two men and a young girl were found tied up and bayoneted; the girl had been raped.Australian sworn affidavits describe a dead native woman tied by her hands and legs to a hut, with 70 condoms lying around her.

Webb listed 36 atrocities against Australians troops. Many were the victims of bayonet practice, repeating the outrage of Tol Plantation. Several soldiers were bound to trees and repeatedly stabbed. At least two were disembowelled, one decapitated, and one bayoneted in the rectum. The heads of several were crushed in. One soldier’s fingers were cut off.Another soldier was tied by a long rope and used as a running target, as shown by his torn shirt and stab wounds in the back. Two men were bound, one on the ground, one to a tree, and slowly mutilated. In Justice Webb’s unsparing language, ‘The man on the ground had his hands tied in front of his chest below his throat…He had wounds each side of his chest and on his forearms. His arms were cut as though he had been trying to protect himself. His buttocks and genitals were cut to ribbons. The tops of his ears were cut off. His eye sockets were missing. He had about twenty knife or bayonet wounds in his body.’26

The victims died slowly, dimly conscious of the use to which their bodies were being put. ‘It took them a long time to die,’ said a sign placed on the bayoneted bodies of Australian troops in New Britain; the same could be said of the victims at Milne Bay.

Webb described the perpetrators as ‘sadists’ and ‘fiends’ who had committed ‘savage’ war crimes in breach of Article 46 of The Hague Convention. Judges rarely seem able to find the language to fit the crime. In this case, perhaps words were unavailable. Four Special Naval Landing Parties—Sasebo 5, Yokosuka 5, Kure 3 and 5—and 10 Pioneer Unit were held responsible for the atrocities.

Those who are determined to hate the Japanese no doubt relish evidence of behaviour that seems to support the most vicious racial stereotype. They are wrong. Most of the Japanese army did not mutilate natives and prisoners, and many ordinary Japanese soldiers were revolted by the cruelty of officers. It is, however, a lame response of revisionist Japanese academics and military historians—who refuse to acknowledge that the rape of Nanking happened, for example*—to bundle up the cruelties of war with the dismissive, ‘all sides committed atrocities’.This won’t do. No doubt the Allies took very few prisoners and, on occasions, committed massacres. But there is no evidence that they subjected individual prisoners—and civilians—to a slow, deliberate and agonising death.

The perpetrators were the navy’s advance landing parties, shock troops brutally trained to subdue any resistance using methods designed to terrify and demoralise the enemy and their suspected native collaborators. What can be said of these men? What can be said of the people who trained them? One searches in vain amid the atrocities of Milne Bay for some sort of explanation. In the absence of any from the Japanese Government, one is left to agree with Evatt:‘[Webb] reveals not only individual and isolated acts of barbarity but also practices which are beyond the pale of accepted human conduct, and which could not have become general without connivance, encouragement and direction of superior officers up to the highest.’

‘If those responsible,’ Evatt added, ‘for these outrages are allowed to escape punishment, it will be the grossest defeat of justice and a travesty of principles for which the war has been fought.’27 Most of those responsible died in coming battles; meanwhile, no Japanese government has officially acknowledged the war crimes or apologised to or compensated the victims’ families.

Of the 2400 Japanese troops at Milne Bay, 612 were reported dead—most of whom the Australians buried—and 535 wounded, a total of 1147. Of the Australian casualties, 161 troops were killed and 212 wounded.

There were very few prisoners. The Australians took a handful. A footnote to a letter appended to the Clowes Report states, ‘The reference to “no prisoners” is not true as eight or nine were captured.’ The Japanese killed all prisoners at Milne Bay.

Of those eight or nine—in a battle involving 6500 troops—one was Sakaki Minoru, a family man and reluctant soldier, who was captured on 6 September suffering from ‘foot trouble’.28 He had lost touch with his unit. He told the Australians that he expected them to kill him. He said he did not mind dying, and would have preferred to commit suicide ‘but had no weapons available to him’. His greatest concern was for his wife.

Months after the fighting ended, unburied Japanese bodies were still rising from the swamps, or bobbing along the banks of the creeks. Many skeletons were found in coral caves along the coast.

A fitting epitaph to this disastrous Japanese affray is the image of two troops found wandering the grasslands by Papuan natives, who pelted them with rocks whenever they tried to rest. At dusk the two soldiers hanged themselves from a tree.29

The Milne Bay defeat had wider ramifications. It was considered extremely hazardous for Horii to attack Port Moresby unsupported by air power from Milne Bay, and on 28 August 1942, Rabaul ordered him to halt ‘at a strategic line south of the Owen Stanley Range’ and await further orders.30 Horii sensed his growing isolation, but pressed on into the mountains.

Victory was sweet for Silent Cyril, to whom ‘the great’ offered grudging congratulations—then later relieved him of his field command. Clowes’s star had risen high enough in the firmament. High-ranking military officers seemed inordinately jealous of each other’s success. Clowes reported on the battle with generous understatement: ‘The troops performed admirably in the face of very adverse conditions.’31

Had the battle for Milne Bay not ended, an enemy deadlier than either side, the anopheles mosquito, would soon easily have exceeded the capacity of men to kill one another. Up to a thousand Australian troops per week caught malaria in the month after the battle, according to Colonel Speight, OBE. By the end of October, virtually the entire Australian garrison at Milne Bay had symptoms of the disease.