Chapter 23

Butcher’s Hill

‘You’d have to be a qualified mountain goat to be able to do physically what they did’

—Private Bert Ward, 2/27th Battalion, on the Japanese at Efogi

That night the Australians dug in high above Efogi saw an extraordinary sight in the valley below: a line of twinkling Japanese lanterns seemed to be guiding the enemy down the steep slope from Myola, bobbing along in a macabre suggestion of festivity. In truth the ‘lanterns’ were flaming lengths of rubber-coated signal wire, abandoned by the Australians.

‘Conceited bastards!’ grunted the intelligence officer, Ray Watson. The lanterns were within range of a Vickers machine-gun, but these had not been brought up—a source of intense frustration for Potts. He wired Port Moresby for air attacks: ‘Quiet night but lights observed coming down MYOLA track into EFOGI from 1830 on 6 Sep to 0200 this morning…Turn all you’ve got from air on EFOGI and MYOLA at earliest tomorrow morning…’1

At dawn eight bombers and four Kittyhawks bombed and strafed the Japanese positions. A suspiciously exact 100 Japanese were said to have died in the raids; but both sides confirm the figure.* Australian satisfaction was short-lived. The jungle canopy offered protection from air raids, and the Allies could not defeat Horii by air power alone. Scorning the bombardment, some 1500 Japanese troops occupied the deserted village of Efogi later that day, and Horii moved his HQ there.

All night the Japanese consigned their dead to funeral pyres that burned in the hills near Efogi. About this time, Colonel Kusunose Masao, the much-admired commander of the 144th Regiment and Horii’s second-incommand, succumbed to severe illness. That day his men had been selected to lead the pursuit, and Kusunose was forced to issue orders from his stretcher, carried forward like a sultan aboard a palanquin.

Fifteen hundred miles away General MacArthur strode about his Brisbane headquarters in high dudgeon. The Allied supreme commander railed at the Australians between puffs on his corncob pipe. MacArthur and the ‘Bataan Gang’ of Americans were forming a bleak assessment of the antipodean army.**

MacArthur persisted in presenting the Japanese land invasion as a sideshow, an irritating irrelevance, as if a junior demon had merely dared to spoil the handiwork of Zeus. The enemy would never succeed over the mountains.2 Privately, MacArthur saw the enormity of what was happening, and not only to the Australian forces: the Japanese advance threatened his career. The flipside of MacArthur’s self-aggrandisement was a gnawing preoccupation with personal failure. To be forced out of the Philippines only to lose Papua and New Guinea would cause irreparable damage to the American general’s tightly coiled ambition.

Skilled at engineering a scapegoat, MacArthur latched onto the Australian officers. On 6 September, he told General George C. Marshall: ‘The Australians have proved themselves unable to match the enemy in jungle fighting. Aggressive leadership is lacking.’3

In this judgment MacArthur cast a dangerous hostage to fortune. The withdrawal from Myola can be directly traced to errors beyond Potts’s control: the catastrophic supply failure; the insistent denial of Japanese land invasion plans (despite Ultra’s warning); the underestimation of enemy strength; and the gross ignorance of the terrain. This trail of incompetence led ultimately to GHQ in Brisbane.

The fall of Kokoda, Isurava and now Myola were admittedly disturbing, MacArthur allowed. From his perspective, the enemy seemed able to conquer at will. The mood at GHQ swung ‘like a bloody barometer in a cyclone’, quipped Major-General Vasey, as an element of panic gripped the command structure. MacArthur’s press-release writing team were put on full alert.

‘[GHQ] is like the militia—they need to be blooded,’4 Vasey remarked. In Blamey’s absence (on another interstate troop inspection), Vasey had the job of relaying MacArthur’s concerns to Port Moresby. He did not relish the task; he and Rowell were old friends. Veterans of the Great War, the two Australian generals had fought three campaigns in the Middle East. They were bemused, to say the least, at the inexperienced Americans’ handling of the situation.

That day Vasey signalled Rowell of the ‘grave fear’ felt by GHQ that the Japanese may capture the Port Moresby airfield. MacArthur ‘feels that present withdrawal policy is wrong and I know it is against your instructions. He urges greater offensive actions against Japs.’5 Rowell was instructed to ‘energise combat action’.6

Amid his tentage on the scorched hills above Port Moresby, Rowell, commander of New Guinea Force, needed no such reminders. Nor did it help to be told that Potts’s withdrawal technically went against orders. Rowell knew better than any in Brisbane the seriousness of the situation.7 He was, after all, defending three fronts in Papua and New Guinea: at Milne Bay, in the Owen Stanleys, and at Lae–Salamaua.

While he insisted later that he never believed the Japanese would capture Port Moresby, the possibility they might get close to the Seven-Mile drome focused his mind. Rowell had the authority to order the destruction of Port Moresby, the airstrip and all unwanted supplies, and head for the hills, as it were, in the event the Japanese reached the coast. He dismissed such a course. He would not countenance a policy that conceded defeat in advance. He resolved, if the Japanese broke through, to ‘drive [the enemy] back by offensive action…the guns must be fought to the muzzle’.8

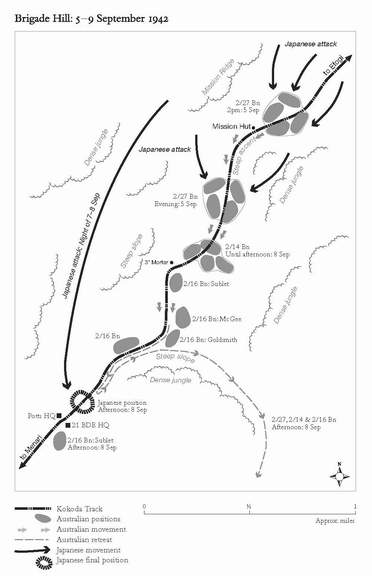

Brigade Hill is a natural citadel, apparently inviolable, at the summit of Mission Ridge, just south of Efogi. The summit and jungle-clad flanks command a strong defensive position. Seeing this, Potts installed his HQ below the knoll at the southern end of the summit, seemingly suspended in the clouds.9 To the west is a steep, thickly forested slope, a near-cliff, the kind of natural barrier to which any commander might feel comfortable turning his back. Across the clearing, like the ancient sentinel of a forgotten creed, stood the ruin of a wooden shack that once housed a Christian mission.

Potts’s troops were strung out ahead, between the summit and the ridge’s north-facing foothills, overlooking old Efogi, a distance of about one mile or so along the track. The fresh 2/27th Battalion was the vanguard, on the hills near the approaches to the enemy-held village.

Potts was in the habit of writing to his wife on the eve of battle. ‘Sweetheart,’ he addressed her on the 6th, ‘Have I neglected you so very badly?…Sorry I can’t talk more…but the main thing is I love you always…Did I comment on the possibility of bringing back a grass skirt? Judy would look ripping in one, and so would her mother…It rains every day…with the little yellow devil being a perfect nuisance…’10

He grabbed a few hours’ fitful sleep. The guns were silent, and the clear night moonless and cool. The alpine air carried the smell of smoke and wet vegetation. Across the valley burned the fires of battle, bombed villages, and Japanese funeral pyres.

Well before dawn on the 8th, Cooper’s troops above Efogi were on the alert for a powerful Japanese offensive. His men were destined for an especially nasty war. Already, he’d lost dozens in two days of fighting, during which they’d held off sporadic Japanese attacks by rolling grenades down the slopes: ‘I don’t know to this day how many thousands of grenades went down that hillside,’ wrote Corporal Frank McLean, MM.11 In fact, during those two days, the battalion had fired 100 rounds of ammunition per man and thrown 1200 grenades, almost exhausting their entire supply.

Grenading the enemy in the darkness was a precise business. The troops used grenades with seven-second fuses. They pulled the pins, counted to four, and then tossed them down the slope. The bombs were meant to explode at the bottom of the valley, after three seconds. It didn’t always work out that way, said one soldier: ‘It was like Russian Roulette in the dark hoping there weren’t any four-second grenades among them.’12

All that night, they heard the Japanese chopping at the vegetation and yelling to each other in the valley below. Suddenly, just before dawn, five enemy companies charged up the hill towards the Australians. This tremendous barrage was, in fact, a diversion from Horii’s real plan—another wide-flanking movement, this time, one of exceptional audacity.

It began the night before. At sunset on the 7th Horii had sent a company led by Lieutenant Sakomoto13 on a wide encircling march to the west. At about midnight, the patrol were halfway up the apparently unassailable western slope to Brigade Hill—site of Potts’s HQ—laden with a Juki heavy machine-gun. ‘Started to climb a steep mountain which takes 11 hours. Detoured in order to come out at enemy’s rear,’ Sakomoto wrote. ‘Slashed through the jungle aided by engineer Tai.’

Without seeing the terrain, it is hard to imagine what happened there. In sum, Sakomoto led about ninety men up a near 45-degree incline, with a machine-gun, through thick forest. It took them most of the night.

Understandably it never occurred to Potts that an attack would come from this direction.

At 5.30 a.m., Sakomoto’s men reached the summit. Potts was returning from the latrine—a pit dug on the far side of the clearing—when he heard a crack, and saw Private Gill, a sentry, slump forward with a bullet in the head. The sniper reportedly just missed the brigadier, who dashed back to his HQ. There was a moment of silence—then suddenly the Japanese were pouring over the threshold. They slammed their machine-gun into place on the summit, and attacked the Australians on both sides—the rear guard of the 2/16th Battalion to the north and Potts’s HQ to the south.

A Dads’ Army of Potts’s staff—cooks, signallers, clerks and batmen, whose average age was over 30—ran forward with revolvers, rifles and grenades, and fired at a range of fifteen yards. One officer rustled up a mortar, and fired it in a near-vertical trajectory.14 But they were forced back by the intensity of the machine-gun fire.

Within moments, the Australian army was cut in half. Potts and his HQ were severed from their forward infantry. Hearing the fire behind them, the Australian rear companies rushed back down the track, and tried to break through the Japanese blockade. The attempt failed. ‘They encircled us at Efogi in an area like that…Well, you’d have to be a qualified mountain goat to be able to do physically what they did’, said Private Bert Ward.15

A saving grace was that Potts’s radio worked (though the Japanese had quickly slashed the telephone line to his forward troops). He alerted his battalion commanders to the encirclement; they ran back down the track. Potts guessed he was probably doomed, and issued what he thought would be his last order: in the event that the enemy ‘wiped out’ Brigade HQ, Albert Caro was to take charge, he said.16

Three Australian companies, led by Nye, Captain Douglas Goldsmith and Sublet, returned to Brigade Hill determined to breach the Japanese positions. Nye’s men burst from the jungle straight into Sakomoto’s machine-gunner, who had trained the weapon on the point where the track broke from the forest. The ‘jungle seemed to vibrate hotly from the…hail of machine-gun fire’.17 Dozens of Australians fell dead across the grass. Further attacks were thought to be suicidal.

On the HQ side of the summit, Captain Bret Langridge, one of Potts’s staff, volunteered to lead a counterattack. Knowing he was going to die, he handed in his identity disc and paybook. He then dashed out, and was shot in the chest within a few yards. As he fell to his knees, he ‘yelled encouragement to his men’.18

The Australians suddenly found themselves sandwiched between Sakomoto’s gun on the summit, and thousands of Japanese troops who were advancing along the track from Efogi. The Australians had two choices: to die in the enclosing vice, or pitch into the jungle. They chose the latter. Elements of three battalions—about 300 men—spilled down the eastern sides of Mission Ridge. The wounded were dragged and piggybacked into virgin rainforest. They included Private Kevin Tonkin, a golf coach from Western Australia. Tonkin was ‘my saddest sight’, said Blue Steward, the 2/16th Battalion’s medical officer: ‘He had a ghastly, gaping wound of the throat, and although my eyes could see only darkness and death, he saw light and hope. They were asking me something with all the mute urgency that eyes can convey…the hardest thing is not to flinch from the gaze of the man you know is going to die.’19 There was neither helicopter nor donkey to spirit Tonkin away. He was carried to safety on the shoulders of his mates, and died four days later on a stretcher, lost in unmapped country.

Seventy-five Australians died in the battles of Efogi and Brigade Hill that day. Japanese losses were 200 killed, and 150 wounded. ‘Corpses were piled high…it was a tragic sight,’ wrote Sakomoto.20 The last diary entry of company commander Lieutenant Noda noted hopefully: ‘Death is a fate. It is no use being pessimistic.’21

Potts’s fighting withdrawal had become a rout. The Australian troops were ‘no longer of any importance as the vital ground in the defence of the brigade position had been captured,’ said one battalion history.22 Their supply and signal lines were severed, and their commander cut adrift from his troops. ‘No orders from [Potts] could be received.’23 No ammunition or rations could get through. The defeated battalions were, ‘cut off without certainty of getting out at all’.24 The lost troops embarked on a wide detour to the east in the hope of reuniting with their commander.

Meanwhile, Potts and his few surviving staff—plus some forty troops who had breached the Japanese positions—retreated down the trail to Menari, from where he sent a bleak message to Port Moresby (the telephone line was still linked south of Brigade Hill): ‘9 Sep: No communications with Battalions since attempted breakthroughs…Attempt failed…CARO previously instructed if BRIGADE HQ wiped out to assume command.’25

Back in Port Moresby Rowell was fully apprised of the catastrophe, and summed up his feelings in an intensely personal letter to his friend, Vasey: ‘Today,’ he wrote on 8 September, ‘has been my blackest since we came…Potts said yesterday “I intend to bash him here”…yet he does nothing except get bottled up…I have thought over my own position in the past few days…I think I must have killed a black cat without knowing it. If I felt I’d mucked things up I would not hesitate to say so, but I feel any decisions I’ve made on major problems have been right & I’ve been knocked back by natural difficulties, by failures in leadership or fighting capacity or by a superior enemy…’

Rowell could be murkily self-indulgent. Yet from the earliest he had consistently argued that Horii would not capture Port Moresby: ‘I hope I’m not wrong this time in saying I’m confident the enemy has no hope of getting MORESBY from the North. His difficulties will now start and I trust we can get him on the rebound…’26

The bad news went straight to the top. Vasey duly informed Blamey on the 9th that Potts’s situation ‘took most serious turn yesterday morning’. The Japanese had succeeded in planting themselves on the track between ‘BATTALIONS and BRIGADES HQ’.27

Rowell readily imagined the groan issuing from Brisbane.

That evening, high in the Owen Stanleys, the Japanese hero of the day, Sakomoto, sat eating a plate of rice. It was the first time he’d eaten rice in three days, he wrote. He rested his triumphant troops at Brigade Hill, later dubbed Butcher’s Hill, and at 4.20 a.m. the next day set off in pursuit of the Australian army, ‘climbing breath-taking cliffs and wading through muddy swamps’.28