Chapter 41

Oivi–Gorari

‘Japan did not lose the ground war in the South Pacific in any single place. There was no equivalent of Waterloo or Stalingrad…Yet if I were to pick one place where the war turned irrevocably against the Japanese, it was at Oivi–Gorari…The [Australians] inflicted a massive defeat on crack Japanese troops at small cost to themselves’

—Eric Bergerud, Touched With Fire

Fed up with the insinuations that he was somehow Allen’s caretaker, Vasey now meant to impose his formidable will on the campaign. He had the comfort of a secure air base and the mountains behind him; the Japanese, on the other hand, were digging in with their backs to the Kumusi River. This knowledge made up his mind: Vasey would deploy his entire division in a single, crushing blow.

He planned to attack on a scale as yet unprecedented in the Pacific War. No Allied army—in Burma, Malaya or Guadalcanal—had yet committed two brigades or greater in offensive action. Vasey prepared to surround and cut off the Japanese with no less than seven Australian battalions—a force of about 4000 men.* He risked ‘having no backstop’; the first time in the Pacific an Allied commander had deployed all his reserve troops in one stroke.

He was racing against time—and not just MacArthur’s and Blamey’s time. Vasey’s army were racked by disease, of which there were more virulent strains near the coast. Every day the sickness rate rose. As they neared the coastal plain, the incidence of malaria shot up (soon it would reach hyperendemic levels). The Australian losses since Myola, ‘exclusive of killed’, were more than a thousand, Vasey wired Herring in Port Moresby. Companies were amalgamated, they were so thin. Dysentery was endemic, especially in Cullen’s battalion as they made their way east.

Ever conscious of the challenge of the terrain, Vasey adopted innovative techniques to get his officers moving—and thinking: ‘One cannot accelerate speed of the individual in this climate,’ he told Herring. Instead, he asked his officers to accelerate their ‘speed of thought and decision’** and ‘to take the route where the Jap is not’.1

The speed of Vasey’s thought alarmed his more cautious staff. When one staff officer wondered whether the huge manoeuvre wasn’t a bit risky, Vasey jabbed a finger at the officer’s chest and replied, ‘I will do anything that [the enemy] will allow me to do.’2 Vasey knew his own mind, and was superb at thinking on the hop. The staff officer soon came around to Bloody George’s way of thinking:‘He knew exactly what he wanted to do. He was quick off the mark, and the clarity of his thought was terrific.’

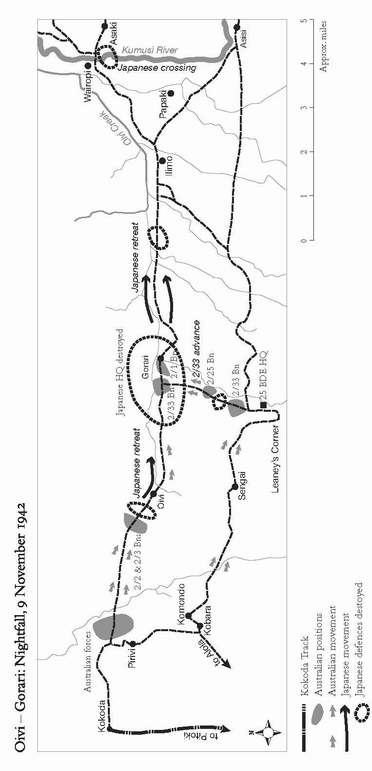

The combat zone was a rectangular area of grassland, rubber trees and clumps of jungle about three miles long and a mile wide, east to west. On the western end, on higher ground, was the village of Oivi; about a mile to the east was Gorari, the Japanese hub, linked to Oivi by the Kokoda–Wairopi track. About seven miles further east was the Kumusi River. There were perhaps 2500 to 3000 Japanese troops heavily dug in between Oivi and Gorari. Palm-log reinforced foxholes similar to those at Templeton’s Crossing pocked the field.

Vasey had sent one brigade3 and Cullen’s battalion along a track parallel to the Kokoda–Wairopi route, as the southern prong of his vast flanking manoeuvre. The rest of his men were ordered to attack Oivi, to the east. For the first time, the Australians had the numbers and the manoeuvrability to attack effectively on the front and the flanks.

On the 7th, Australian mortars and American bombers pounded the Japanese bunkers at Oivi, followed by a failed attack that claimed 47 Australian casualties. The next morning low-flying American fighters strafed the Japanese bunkers at Oivi and along the track, and dropped eight 20-pound bombs on their bunker fields. The Australian troops noted with relief that the fighters ‘didn’t hit us on this occasion’.4

Vasey had no intention of sending costly ‘ram-like thrusts’ towards the Japanese front line. His trump card was the wide flanking march of the 25th Brigade and Cullen’s battalion. The open terrain helped—this was easier country than Eora Creek. Yet many were sick, and the speed of movement exhausted them. On the 4th, Cullen’s men camped on the edge of a razorback, before descending into the Oivi valley: ‘That night,’ wrote Cecil Traise, ‘I was lying across the razorback with part of my legs hanging in space, rain simply pelted down and the smell of rotting leaves gave the impression that I had fallen into a cesspit.’5

The next day they entered the village of Sengai, and made a bitterly sad discovery: the skeletons of five Australians dead in their stretchers, with two others, including Metson, lying nearby—final proof of the fate of Fletcher’s party.

On the 8th, having gone too far and then been forced to retrace their steps, Cullen’s men regrouped at Leaney’s Corner with troops of the 25th Brigade. The combined Australian force prepared to encircle the Japanese at Gorari.

Patrols had already clashed for days between Leaney’s Corner and Gorari, under sheeting rain, with heavy casualties. These were exceptionally savage. One battalion suffered 37 casualties while fighting along the track to Gorari on the 9th, its costliest day.6

But slowly the Australian trap was being set. To the west, one battalion had wedged itself between the enemy positions at Oivi and Gorari; to the south-east, another blocked any retreat to the Kumusi River; and to the south two more closed in from Leaney’s Corner. The Australian troops began to squeeze the Japanese in a three-way vice, from the east, south and west. ‘It was clear that the next day or two must bring forth a slugging match. Desperate Japanese would try to fight out of the trap…’7

The first slugging began at Oivi. The Japanese realised they were cut off from their Gorari HQ—by the Australians sandwiched between the two—and hemmed in by the Australians to the west. Reminiscent of Potts’s experience at Brigade Hill—though on a larger scale—Japanese patrols tried to smash through to Gorari. They failed to breach the wall of Australian machine-guns.

Lieutenant Sakomoto, who’d inflicted such damage on the Australian withdrawal at Brigade Hill, sat in his dugout and prepared to face battle. ‘The Australian offensive has begun,’ he wrote on 9 November. ‘They have encircled us, while all morning, their planes bombed and strafed us.’

On the 10th he made his last entry: ‘The 1st battalion is leaving Ilimo at 2 o’clock to cover our retreat. Decided to withdraw from this position at 10pm. The Yazawa Butai will be our cover Tai. Situation in the rear is not clear.’8

Sakomoto died fighting—a true example of the ‘warrior spirit’.

Meanwhile, the Japanese trapped in Gorari tried to blast their way out of the Australian cordon, and wheeled up a mountain gun to the western edge of their perimeter, 400 yards from the Australian dugouts.

Shelled for three hours, the Australian 2/33rd Battalion was almost blown apart. ‘With only log cover or bayonet scratched holes, this grim experience shattered nearly all in D company.’9 Some abandoned their positions—at which the commanding officer pulled his revolver and threatened to shoot the fleeing troops, who were forced back to the front. Eventually the shelling ceased.

On the night of the 11th the Australians ‘were gathering themselves for the kill’, in the official historian’s vivid phrase.10 The two armies met on that moonless night in pouring rain across a landscape of splintered rubber trees, jungle copses and muddy grass. The Australians crept across the field towards the Japanese perimeter at Gorari village, their main camp. Cullen’s men wheeled round to the north of the enemy—utterly confusing them. The other units pressed in from all sides.

Suddenly hundreds of Japanese tried to break out. They rushed for escape routes; suicidal officers ran yelling at Australian guns. Others attempted to bayonet charge their way out. Medieval scenes of hand-to-hand combat flared in the darkness. Tracer fire and exploding grenades flashed on the running shapes. Hunched figures squatted in the mud, clasping wounds; some crawled back to their bunkers. Medics scrambled about to locate the cries of the wounded.

Just as suddenly, the breakout ceased, offering a few hours’ respite. The Australians troops waited in the mud for the resumption, ‘…few slept. Throughout the dark hours fire was heard on all sides, occasionally flaring up to a crescendo. Japanese were heard and seen moving about on all sides.’11

Runners sent back with messages lost their way. Often they ran headlong into roaming Japanese. Private George Gates, sent back to his brigade HQ, was later found, bayoneted by wandering Japanese.12 Another runner, Lance-Corporal Cyril Daniels, was shot dead after walking twenty paces into the scrub. Company commander, Captain Brinkley, lay in the open ground with a gaping stomach wound. Hauled back to safety, he died a short time later.

About midnight a piercing scream stunned an Australian platoon. A Japanese soldier had infiltrated and tried to bayonet Private Bowen, an immensely strong bushman nicknamed ‘Yippee’. Yippee grabbed the blade, wrenched both bayonet and rifle out of the Japanese soldier’s hand, and hurled it like a spear at his fleeing attacker. The rifle stabbed the Japanese infiltrator in the back.13 Bowen received deep wounds in his hands.*

The slaughter continued all the next day, beginning with a wave of Australian bayonet charges. At dawn on the 11th, they surprised a group of Japanese troops sitting down for a breakfast of rice and milk. ‘It’s apparently not etiquette to fight [at] mealtime,’ wrote one Australian. ‘They were… eating their breakfast at the critical moment. The attack became a slaughter and the Japanese were wiped out to a man, with amazingly light casualties to our side.’

The enemy dead were believed to be members of 144th Kuwada Battalion, the unit responsible for the massacre of the Australians at Rabaul. ‘So justice was done,’ concluded Bert Kienzle, years later, in an address to the 39th Battalion Association Pilgrimage.14

Gorari became a mass killing ground. The stupefied Japanese were shot, bayoneted or grenaded without restraint. The scale and fury of the Australian assault shocked even the enemy. Three Australian battalions poured ceaseless automatic fire into the Gorari dugouts. In a cleared hollow, a hundred yards from the main battle, a large enemy group were eating dinner, resigned to death and apparently careless of the battle raging around them. All died where they sat.

Many Japanese refused to surrender. Bullet-riddled soldiers kept running at the Australian guns, brandishing their swords or revolvers:‘I didn’t think he would ever fall, and he got within five yards of me before he dropped,’ said one machine-gunner. Corporal Harrowby St George-Ryder was changing his magazine when a Japanese officer, waving a flashing sword, charged, knocked off the Australian’s steel helmet, and slashed his face and head. In reply, St George-Ryder kneed the Japanese in the groin and the pair wrestled on the ground until another Australian dispatched the swordsman.

The fighting ceased on the night of the 11th, and dawn revealed the extent of the slaughter: 580 Japanese bodies were counted. ‘In the jungle area near Gorari,’ Blamey informed the Australian Government, ‘the enemy left no less than 500 dead. A pleasing feature is that in spite of the closeness of the fighting, our casualties are very much less than the enemy’s and our men are definitely superior to them in jungle fighting…’15

Australian casualties were remarkably light. In the final battle, on the 11th, one battalion16 suffered just seven dead and seven wounded. The build-up to the entrapment was costlier, with 123 officers and men wounded and 48 killed between 8 and 10 November.

A handful of prisoners were taken. A few starving waifs fell into Allied hands—or awoke to find themselves in captivity. Private Yamamoto Kiyoshi, who was caught south of Gorari on 9 November, had acute malaria. He was captured, sleeping at noon. He wept and broke down under interrogation, stating that he’d spent a month in hospital after which he was carried forward on a stretcher to fight.

Of his capture he said he felt ‘nothing but the feeling of shame to the Emperor, to the country and to one’s family’. He preferred to die rather than return to Japan, ‘but if your customs do not permit this I will be a model prisoner’.17

Another was Tsuno Keishin, a superior private, knocked out when a bullet struck his helmet. He said he enjoyed listening to Australian radio broadcasts, even though they were officially dismissed as Dema Hoso (demagogism).

Australian battalion histories mention only one prisoner, ‘a boy, short and dumpy, with a round fat face’. The boy sat on the ground in a daze after ‘a terrific thump’ to the side of the head from an Australian rifle butt. He was tied to a tree, given a groundsheet and a portion of rice, and left to die.18

A trawl through Japanese bodies yielded Australian letters, photos and documents. Captain Sanderson’s pay book and his German Mauser were found on one body. The most valuable find was a Japanese plan to inflict the same encircle-and-destroy tactic on the Australians; it delighted Vasey that his speed of thought had outpaced Horii’s by a matter of hours.

Milne Bay was the first land defeat of the Japanese. But Oivi–Gorari was the first decisive strategic land victory in the Pacific War. It broke the Japanese hold on the track and forced them back to the coast. One brave American historian dared to suggest it was a ‘turning point’ in the Pacific War:

Japan did not lose the ground war in the South Pacific in any single place. There was no equivalent of Waterloo or Stalingrad…Yet if I were to pick one place where the war turned irrevocably against the Japanese, it was at Oivi–Gorari on November 5, 1942…The [Australians] inflicted a massive defeat on crack Japanese troops at small cost to themselves. Rarely would the Japanese fight Australian troops in open battle in the future. When they did the result was defeat.19

The Australian victory drew rapturous praise from Port Moresby. Vasey had delivered the coup de théâtre. On the 14th Blamey acknowledged, ‘The greatest factor in pressing the continuous advance has been General Vasey’s drive and personality.’20 Herring declared that Vasey had made ‘the Japanese dance to his tune’.

Vasey generously passed on their congratulations to his officers and men, and resumed the pursuit. His motto became ‘Buna or Bust…and we will not bust!’