Chapter 45

Gona

‘You will tie a bayonet on a pole. Those without bayonets will…carry a wooden spear’

—Yokoyama Hospital Bulletin, order to the sick and wounded, Gona–Sanananda, November 1942

In November 1942 the war spilled onto the northern coastal plain of Papua. The littoral dictated a different kind of fighting. The predatory manhunt, the war of stealth, became a pitched battle across swampland, coconut groves, beaches and coarse grassland.

The Allies prepared for a campaign of total annihilation: ‘an exercise in extermination’, as decreed by Allied High Command.1 The Imperial Japanese Army dictated this outcome: the enemy refused to surrender and would fight to the last man. Their sick and wounded were ordered to join the coming battles.

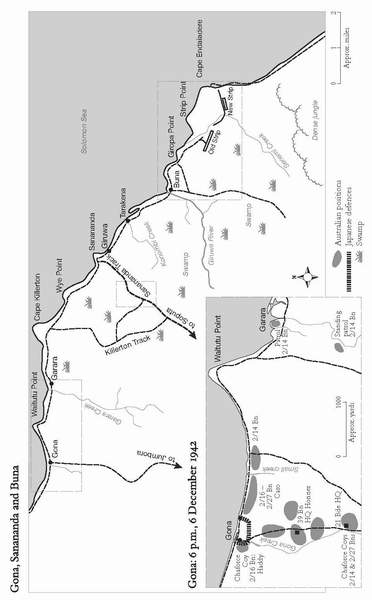

The battlefield was a rough semi-circle about ten miles wide and five deep stretching from Gona in the west to Buna/Cape Endaiaere in the east, and inland as far as the village of Soputa. At the centre, on the coast, was Sanananda/Giruwa, site of the Japanese headquarters and main hospital. War had scarred the landscape beyond recognition; air raids had ripped apart the forests and strewn the area with craters. Reverend Benson’s Garden of Eden was a wasteland.

The paradise that had bewitched the missionary held little allure for the Australian army. Blamey described the Gona–Buna shoreline as ‘about as vile a country as any that exists’.2 Scraggy jungle and coarse kunai patches; fetid swamps, awash with tidal rivers; pouring rain, steaming heat and nightly mosquitoes—none of these was conducive to human habitation. There were no roads; the tracks that existed were mud, and seemed to empty into swamps, or disappear into tall grassland.

Diseases of the most virulent kind infested the area. In 1942 the swamps were malarial cesspits and the grasslands were home to tiny mites, carriers of scrub typhus. ‘It was the edge of the known world,’ remarked Frank Taylor, who regularly visits the region today.

The Japanese saw the Papuan beachhead as supremely important to their overall plan. They were determined to hold the Allies there while they fought the American marines at Guadalcanal, an island they vainly hoped to recapture. In early November Tojo personally informed General Imamura, supreme commander of the South East Area Armies, that ‘the welfare of our nation depends on this operation, so important is it. Therefore I hope you will make your plans well and ease the Emperor’s mind.’3

Vasey’s ‘tiger’ was immobilised. The Japanese had their backs to the sea but were extremely well dug in. They had built a coastal fortress of interlocking bunkers, stretching from Gona in the west to Buna in the east. This network of little underground forts locked up the firmer ground. Like clams stuck to a rock pool, hundreds of foxholes pocked the soggy coastal plain. They were an extraordinary feat of engineering. Their frames were of foot-thick palm trunks supported by steel and oil drums packed with sand, and virtually impregnable to mortar, rifle and machine-gun fire. Only a direct hit from artillery or tank shells, or a grenade thrown in through the fire slits, was likely to destroy the occupants. A flamethrower might have roasted the enemy alive, but none was available until later in the war. Air bombardment repeatedly tried, but usually failed, to find its targets.

These formidable structures were expertly camouflaged and well supplied—at least in early November—with enough food and ammunition for weeks of resistance. The bunkers were indiscernible, even at close range; only tiny rectangular fire slits revealed their locations. They were ‘so well camouflaged with earth, rocks, palm fronds, and quick-growing vegetation that they could not be detected even from a distance of a few yards’.4 Bunkers in kunai grass were festooned with bundles of grass; those in palm groves were ‘covered with coconut leaves and fallen coconut husks’.5 Palm fronds obscured the fire slits, and advancing troops often overlooked the pillboxes until they were right on top of them.

The holes were mutually supporting, connected by lateral fire trenches along which, under attack, the Japanese raced to adopt new firing positions. This confused approaching troops who, upon entering the bunker fields, found themselves suddenly trapped by enfilading fire. The approaches were invariably across open grassland, river bank, or through swampland.

The defensive shield was not all underground. In the treetops, heavily camouflaged sharpshooters sat wedged between palm fronds and coconut clusters. Snipers strapped themselves to the trees, and slept there. Caught in this patchwork of invisible artillery and aerial sniper fire, an unsuspecting Allied platoon had little chance of survival.

The Japanese gunners lived in these underground hives for three months; they ate, defecated and slept in the bunkers. The heat was intolerable, the mud floors awash with seeping swamp water. Troops emerged for night attacks, supplies, and to meet reinforcements. Standards of personal hygiene rapidly deteriorated; when forced into daylight, the Imperial Army was barely recognisable as human.

Thousands lay in wait for the Allied armies in such conditions, all along the coast. Estimates of their total strength varied from 5000 to 13,000. Most were fresh troops, landed during the Owen Stanleys campaign. Their actual numbers varied during the three months of coastal fighting. A US army intelligence report, dated 18 November, placed total Japanese strength in New Guinea at the time at 8000.6 Assuming many of these were at Wau, Salamaua and Lae, the forces at Gona–Buna at that time were probably at the lower end of the range. * But they were being steadily reinforced: on 17 November a new commander, Colonel Yamamoto, arrived to lead a fresh battalion and reinforcements for the 144th Regiment.

In the Gona–Buna region the Allies slightly outnumbered the Japanese: the Australians fielded four, albeit severely depleted, brigades; the Americans, three regiments. There were in total about 7000 Allied troops.

The enemy lacked air cover; Japanese aircraft in New Guinea numbered just 32 fighters and ten bombers in late November. This made reinforcing the coast extremely difficult; Japanese barges full of fresh troops were sitting ducks for Allied strafing raids.

US intelligence warned, however, of the immense pool of Japanese manpower in the region: they could deploy thirteen divisions to the southwest Pacific without weakening their grip on Manchuria and North China. Some 80,000 men were available to reinforce New Guinea—but only if they regained air supremacy. Hence, it was crucial for the Allies to protect their air bases at Kokoda, Popondetta and elsewhere.

Partly for this reason, MacArthur decided not to bypass the Japanese and let them wither on the vine—‘rot and starve’, as one Australian politician later put it.7 While Blamey favoured ‘starving out’ small pockets of the enemy,8 he fully backed the plan to clear the beaches of enemy resistance. The lingering Japanese threat endangered Allied air bases at Kokoda and those under construction at Dobodura.9 The Allied thrust north depended on unhindered air power, as General Kenney reiterated.10 The Japanese must be ‘destroyed in detail’—and no one better understood this than Vasey, who drove his men with the resolve of a big game hunter.

At Gona, the bunkers formed a perimeter around Reverend Benson’s old mission, and ran along the beachfront to Gona Creek, over a distance of about three hundred yards.

In mid-November, flush with their victory at Gorari, the Australian army drew up a few miles south of the coast. It was a dangerous zone. Japanese stragglers were desperately hungry, and at least one Australian soldier was found garrotted in the scrub, with his rations and rifle stolen.

The first to arrive were the advance troops of the 25th Brigade. They encountered a strip of jungle interspersed with palm groves and kunai grass clearings. To the west of the village a swamp of sago palms and mangroves merged with Gona Creek, which emptied into the sea.

Perhaps Porter’s words resounded in some soldiers’ minds, as they surveyed this paludal land. ‘It is possible,’ he wrote earlier, ‘to brave mosquitoes, leeches and mites while wading through them; but there is a limit to the endurance powers of troops, particularly if the swamp is unbroken with dry land on which to rest.’11

The battle of the beaches erupted across the whole front on 19–20 November. Japanese positions at Buna, Gona and Sanananda were bombed from the air, and ‘softened up’ with long-range artillery.

Along the coast to the east a fresh American regiment, dubbed Warren Force, and an Australian independent company, attacked Buna; Sanananda and Gona were left largely to the Australians. For the first time, American troops fought alongside the Australians in a joint Allied action. The troops went into battle expecting a frail adversary, starving and sick.

At the allotted time, a heavily reduced battalion of the 25th Brigade—weary after weeks of fighting in the Owen Stanleys—rose and charged the Gona bunkers. They ‘cheered and yelled’ as they advanced; and suddenly found themselves enveloped by ‘a most intense fire from the front and flank’.12 Twenty-four men were killed and 42 wounded in that single charge.

It set a depressingly familiar pattern. The Japanese machine-guns repulsed wave after wave. After their victories over the mountains, the Australians ‘passed from elation to a sobered…assessment of the [enemy’s] unexpected strength…to exhausted impotence’.13

Within two weeks, the rising Australian casualties drew no less than seven battalions into the Gona maw. They were thrown piece-meal into frontal attacks as they arrived. Brigadier Eather, commander of the 25th Brigade, ordered another attack on 23 November. It, too, was repelled, with 64 casualties. And on the 29th, two ‘fresh’ units (including the 2/27th, the ‘lost’ battalion that had been forced into the jungle at Efogi) sustained 87 casualties, for little gain.

Behind these statistics were scores of young men who, on orders to charge, stood up and ran across no-man’s-land or waded through swamps into enemy machine-guns. The dead and wounded lay on open ground, within dozens of yards of the enemy. Their bodies could not be retrieved until nightfall; the wounded groaned through the days, a constant reminder of Allied impotence against hidden machine-guns.

Brigadier Eather realised he didn’t have the strength to dislodge the Japanese. He decided to contain them, until reinforcements arrived. This didn’t always work; the Japanese were prone to creep out of their bunkers at night and launch bayonet charges.

The enemy clung to their positions at Gona with their usual, dogged will. They had little food—less than a handful of rice per day. They scratched crabs and mussels from the beach, and cooked the occasional octopus.

Their bunkers shook and sometimes collapsed under daily air and artillery bombardment. Aerial photos show the bunker fields strewn with bomb craters. Inside these caverns human life somehow persisted. There was a bench, a hurricane lamp—rarely used—dirty piles of rice, if available, and ammunition. The Japanese rotated the manning of the guns, 24 hours a day; sentries sat with field glasses in the fire trenches.

Hysterical orders inveighed against any thought of capitulation. On 19 November, for example, the commander of the Yazawa Butai at Gona told his men: ‘It is not permissible to retreat even a step from each unit’s original defensive position. I demand that each man fight to the last. As previously instructed, those without firearms or sabres must be prepared to fight with sharp weapons such as knives or bayonets tied to sticks, or with clubs.’14

The sick and wounded were ordered to take up arms. Medical officers, incredibly, were given explicit instructions to fight. Yokoyama ordered his medical corps on the day the bombardment began to ‘make combat preparations and make up your mind to stick with our patients to the very end. You must not retreat…Do not be fooled by rumours. Do not give way to hardships…I pray that you will go down fighting to the last man.’15

A field doctor dutifully relayed this order to hundreds of sick and wounded men lying on the ground at Giruwa on 21 November: ‘I am filled with sympathy for you who are sick in bed but remember, you are glorious Imperial Japanese soldiers. I pray that you will not be fooled by rumours and that you will not give way to hardships…The hospital staff will stick with you to the very end.’16 Later that day the doctor wrote in his log: ‘Heavy bombing since dawn. Instructed the patients and staff to expect the worst.’17

Worse came on 28 November. The Japanese deemed unfit for combat were ordered to sell their ‘pistols, swords and binoculars’ to the men of the Nankai Shitai and Yazawa Butai returning from the Kumusi River (many survivors of Horii’s retreat had lost their weapons during the river crossing). The wounded were told that their weapons should go to the front ‘to take the place of you not being able to go there yourself. You would be doing this for the sake of your country.’18

Weaponless and starving, the walking wounded would, if worst came to the worst, ‘take up arms and go into combat’.19 The request defied the realms of medical possibility. At Gona and Giruwa, the troops were to rise, as by a miracle, and fight—their commanders had decreed that the Japanese spirit would triumph over terrible wounds and debilitating sickness. They were told to ‘tie a bayonet on a pole. Those without bayonets will…carry a wooden spear. Everyone must carry a spear and be ready for an attack.’20 The next page of the Yokoyama Hospital Bulletin is appropriately blank.

Thus the most disciplined army in the world was reduced to carrying primitives weapons. It brings to mind the Nazi panzerfausts—boys on bicycles—sent into battle against Russian tanks at the fall of Berlin.

Repeated failure exasperated MacArthur, who showed signs of impulsive, even eccentric behaviour. One of the supreme commander’s most erratic moments came in early December, when late at night he sent a message to Blamey via the latter’s adjutant, Norman Carlyon.

‘One night at Moresby,’ recalls Carlyon, ‘I was wakened about midnight…by a despatch rider from MacArthur’s HQ about seven miles away. It stated: “Gona will be captured at dawn.” I went across to Blamey’s tent and woke him.’

A bleary-eyed Blamey shone his torch on the message and exploded: ‘Bloody rubbish!’ he said. ‘I wonder if MacArthur knows what it takes to mount a battle.’21 Blamey promptly switched off his torch and went back to sleep.

In late November the Japanese blew apart the Allies’ rosy scenario. In pouring rain they landed hundreds of reinforcements at Kumusi, bringing their total combat strength in the Gona–Sanananda region to more than 5000.*

On the 29th, with strong air support, four enemy destroyers replete with 800 troops, including a complete battalion22 and HQ unit, tried to land, but were forced back. Five hundred troops then landed successfully in early December. A new leader, Major-General Yamagata Tsuyuo, was sent on the orders of General Adachi, commander of the Eighteenth Army, in Rabaul.

Yamagata had told his men they were headed for a ‘lightning attack’ in a battlefield of great hardship. ‘The health situation is extremely bad,’ he advised. Nonetheless, ‘I have not the slightest doubt that you will conquer hardships…and that with one blow you will annihilate the blue-eyed enemy and their black slaves.’ The war in the South Seas, he added, ‘will be determined by the success or failure of this operation…carry this struggle to the end.’23

The Japanese moved swiftly along the beach from the west towards Gona Creek. A few volunteers of Chaforce (a unit intended for guerrilla-style activity), led by Lieutenant Alan Haddy, were the only Australians blocking their path. They were based at Haddy’s HQ, nicknamed Haddy’s village, on the west bank of Gona Creek. His men had held this isolated flank for two weeks; 64 of Haddy’s 109 men had already died. Friendly fire hadn’t helped; on several occasions Allied aircraft mistook Haddy’s village for the enemy, and strafed them; even Allied artillery fired a few shells at him in error.

On 5 December Haddy and his remaining twenty volunteers prepared to face the first 200 Japanese reinforcements then advancing along the coast. Sitting in his dugout under one of the beach huts, Haddy knew the situation was hopeless. If he stayed, he and his men would die. So he sent the sickest back to Brigade HQ, and organised the phased withdrawal of the rest.

Only he and a sentry remained when the Japanese overran Haddy’s village. A grenade killed the sentry; Haddy fought on, and died in a hail of bullets. Later, when the Allies recaptured the position, they found a ring of Japanese corpses around Haddy’s beach hut, with his body beneath it. A battalion diary noted, ‘[He] ordered the withdrawal stating that he would stay to the last…Haddy was always placing himself in such positions to enable his men to get out…’24