Mid-Sunday morning in Los Angeles, drumbeats and the ringing of a bell open a service in a temple of the Buddhist Churches of America (BCA), the oldest institutional form of Buddhism in the United States. Despite the drum and bell, commentators have often observed that BCA services, with their hymn singing and sermons, resemble those of American Protestantism, which is taken to be evidence of the assimilation of the BCA into mainstream American society. To a great degree this is true. After more than a century in the United States, the Japanese Americans who compose the bulk of the BCA membership have wrestled in many ways with the Americanization issues faced by racial and religious minorities. But even the most casual observer will note substantial differences between the temple and a Protestant church, the most conspicuous being the altar, with its centrally located, burnished image of Amida Buddha.

Close attention to elements of the service that are familiar—readings from scripture, remembrances for deceased members of the congregation, and birthday congratulations for children—reveals some further, more important differences of a philosophical or, as a Christian might say, theological nature. Most conspicuously, the first of three congregational chants, which are led by the priest and followed by the people sitting in the pews in soft, monotone chant, is called the Three Respectful Invitations:

We respectfully call upon Tathagatha Amida to enter this dojo.

We respectfully call upon Shakyamuni to enter this dojo.

Among the most venerable of the buddhas and bodhisattvas, Amida Buddha is central to the Pure Land tradition of which the Buddhist Churches of America is a part. This Amida image and altar are found in the Midwest Buddhist Temple in Chicago, Illinois, one of a network of temples established by Japanese Americans since the end of the nineteenth century.

PAUL NUMRICH

We respectfully call upon the Tathagathas of the ten directions to enter this dojo.1

This is followed by additional recitations, including the phrase Namo Amida Butsu, a key element in BCA practice, referred to as the Nembutsu.

Rituals are seen by scholars of religion as windows into the larger religious worldview of a community. This ritual is a glimpse into the landscape of Buddhism in America, but only into one of its many traditions, Jodo Shinshu, the True Pure Land school, founded by the religious reformer Shinran in the thirteenth century. There are many forms of American Buddhism and many different Buddhist rituals, most of which have their origins in Asia but are being transplanted and adapted to the United States.

Later that Sunday night, in the living room of an apartment in Los Angeles’s Wilshire district, a group of about twenty people, mostly Anglos but also several Latinos and African Americans, sit cross-legged with their shoes off on the living-room floor. They are grouped before an altar that appears to be a small version of the altar in the BCA temple. But instead of a statue of Amida Buddha, this altar contains a scroll called a gohonzon inscribed with Japanese characters. These people are members of Soka Gakkai International, a group of lay Buddhist practitioners in the Nichiren tradition of Japan, which has flourished in this country since the 1960s.

No priest leads the chant, but the woman hosting the meeting begins by ringing a small bell and intoning the phrase Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo while facing the gohonzon. A moment later, those assembled join in and the entire group bursts into a rapid, highly energetic recitation of passages from the Lotus Sutra, one of the most important texts of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition in east Asia. After about a half hour of chanting, one member leads the rest in studying an aspect of Nichiren’s philosophy, much of which is contained in his letters, or Gosho. Afterward, a number of members make informal testimonies about how Nichiren practice has transformed their lives.

Whether they take place in a public temple or before a home altar, rituals such as these are basic expressions of the Buddha dharma, the teachings of the Buddha, and have been for many centuries. Many Buddhists refer to them as their practice, a term that conveys both their repetitive character and, more important, that these techniques are practiced, often for many hours and on a daily basis. This is particularly the case with sitting meditation practice, which is used to cultivate a state of awakening many Buddhists call Buddha mind or Buddha nature.

Sitting meditation is central to all Buddhist traditions that have a strong monastic component, such as Zen, Tibetan Vajrayana, and the Theravada tradition of southeast Asia. But if one were to observe Buddhists from each of these traditions meditating side by side, there would be few differences to note, aside from small details like the color and shape or presence or absence of their meditation cushions. Meditation practices are designed to transform consciousness, and most of them are based on close attention to the intake and outflow of breath. All are used to cultivate the state of consciousness the Buddha attained some 2,500 years ago in India. All look more or less the same from the outside, but significant matters of technique and style differentiate them.

Millions of Americans who know little about Buddhism are familiar with Zen and the idea of Zen meditation, if only in a very general sense. Like Jodo Shinshu and Nichiren Buddhism, Zen is a Japanese tradition, and it shares with these other traditions many details of liturgy—altars, images, bells, and chanting. But the tenor of Zen is quite different. For most of its history in Asia, Zen meditation was practiced primarily by monastics, while the practices of Jodo Shinshu and Nichiren Buddhism have been more associated with the religious life of the laity. Only in the past century have zazen and other monastic meditative practices been widely taken up by laypeople in Asia, Europe, and the United States.

Many Americans think that Zen is a Buddhist tradition without formal ritual, which is not really the case. Zen was first introduced into this country in books that led many Americans to think of it as a philosophy rather than a religious tradition. People also tend not to think of Zen sitting meditation, or zazen, when a practitioner might face a wall or sit with downcast eyes for hours, as ritual activity. But daily or even twice-daily stints of Zen sitting meditation, during which a practitioner notes the movement of his or her mind, help to structure the lives of many American Buddhists, one of the primary functions of ritual. Zazen is also embedded in other, smaller rituals such as gassho, or bowing, and the making of offerings of water, food, or incense to an image of the Buddha.

Zen meditation also takes other forms such as oryoki, in which contemplation is combined with communal eating in a ritual form that requires the skillful use of wooden utensils, nested bowls, and carefully folded napkins. To do oryoki well requires practice. Note the bemused discomfort expressed by Lawrence Shainberg, a long-time American Zen practitioner, when he first encountered eating oryoki-style at an American monastery in the Catskill Mountains outside New York City. “Clumsy with my bowls, I make more noise, it seems to me, than everyone else in the room combined. I have completely forgotten the elaborate methods of folding, unfolding, unstacking and stacking.… The harder I try, the clumsier I get. Rational it may be, but the ritual seems a nightmare now, one more example of Zen’s infinite capacity to complicate the ordinary.”2

In contrast, many Tibetan Vajrayana meditative practices are based on visualizations, which is a very different meditation technique. During a visualization, a practitioner, who to an observer might appear to be simply watching the breath, is engaged in conforming his or her body, speech, and mind to an image of one of the many buddhas found in the Tibetan tradition. Visualizing a buddha entails sustained concentration, whether it is done in a richly decorated dharma center in Vermont, a simple retreat hut in the Rocky Mountains, a rented conference room in a hotel in Atlanta, or at home. But in any case, a Tibetan visualization is a rigorous form of meditation that may take a number of years to do well, which is one of the reasons Buddhists call it a practice.

Theravada meditation techniques are also practiced by many American Buddhists. In the excerpt below, Mahasi Sayadaw, an Asian teacher who taught a number of Americans vipassana or insight meditation, describes how to develop insight using a technique often called noting, naming, or labeling, a basic practice in dharma centers across the United States. The point of this meditation is to heighten one’s insight into mental processes such as thinking, intending, and knowing and into unconscious physical movement, in an effort to cultivate detachment from the mind’s incessant activity and bodily instincts. Sayadaw is describing how a practitioner, thirsty after many hours of sitting, can continue to develop insight even as he or she gets up to take a drink.

When you look at the water faucet, or water pot, on arriving at the place where you are to take a drink, be sure to make a mental note looking, seeing.

When you stop walking, stopping.

When you stretch the hand, stretching.

When the hand touches the cup, touching.

When the hand takes the cup, taking.

When the hand brings the cup to the lips, bringing.

When the cup touches the lips, touching.

Should you feel cold at the touch, cold.

When you swallow, swallowing.

When returning the cup, returning.3

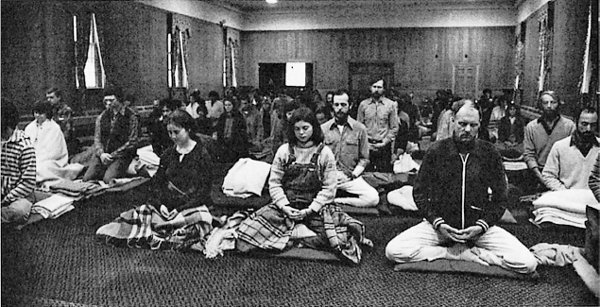

Sitting meditation is a central ritual in many Buddhist traditions and is of particular importance among converts in the United States. At the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts in the 1970s, a group of Americans are engaged in vipassana meditation, a form most closely associated with the Theravada tradition of south and southeast Asia.

INSIGHT MEDITATION SOCIETY

In an effort to Americanize the dharma, some converts advocate divorcing meditation from other rituals that play a part in Buddhism in Asia, viewing them as unnecessary elements of Asian culture. Others, however, maintain and adapt them to American settings. In a monastery in California, a small group of people, both Asian immigrants and Anglo converts, can be found most mornings re-creating a ritual whose origins date from the earliest days of Buddhism. Just after sunrise, they bustle about in a small, informal kitchen preparing breakfast for the monks of the monastery. As laypeople, they have little intention of taking up monastic discipline, but express their devotion to the dharma by providing support for monks who have chosen to devote their lives to study, teaching, and meditation. A half hour or so later, four men, one American and three Asians, file down from their retreats to the kitchen, dressed in the ochre robes of Theravada monks of southeast Asia. There the laity serve them a few spoonfuls of rice, a symbol of the meal and a form of religious offering. Shortly thereafter, the monks eat the breakfast prepared for them in the temple up on the hill. Afterward, the laypeople and monks may gather together for chanting or to engage in consultations, after which the laity consume the remainder of the meal.

This kind of activity can often be observed in many Buddhist temples in most major American cities. Such rituals play a particularly important role among Asian American Buddhist immigrants, who are re-creating their received religious traditions in immigrant communities. Ritual acts such as making prostrations, doing Buddha puja, celebrating Vesak, and taking refuge (all of which will be discussed in the following chapters) are the bread and butter of the religious life of many American Buddhists, as familiar to them as baptism and Sunday churchgoing are to American Christians. But there are also new rituals only now taking form here as the result of religious experimentation. Some Buddhists, both European American and Asian American, are beginning to mix elements of practice drawn from the different traditions of Asia that are now found in this country. Others, primarily European American, are experimenting with creating new Buddhist rituals by adding elements to dharma practice drawn from other religions, be these wicca (western witchcraft), ancient goddess spirituality, the shamanic practices of Native Americans, Judaism, or Christianity.

All these rituals, whether chanting the Nembutsu, sitting zazen, or feeding monks, provide the observer with glimpses into the landscape of American Buddhism. By many Americans’ standards, it is an exotic terrain of unfamiliar religious convictions and foreign practices, but it is all a part of America’s multicultural and religiously pluralistic society in the making. From a historical perspective, American Buddhism is also an epoch-making undertaking. One of the great religious traditions of Asia is moving west. For about four hundred years, western missionaries, explorers, scholars, and seekers probed Asia, wondered about Buddhism, and studied it. A few even practiced it. The groundwork for the transmission of the dharma to the West was prepared by many people over many years, but the emergence of the dharma as an important element in American religion is a development that by comparison occurred only very recently.

What is American Buddhism? During the 1980s and ’90s, many Americans were debating among themselves what Buddhism was in this country and what they wanted it to be. They came up with many different ideas about how to create American forms of the dharma, so there is not a single answer to that question, nor is there likely ever to be. There is not one American Buddhism, any more than there is one American Judaism, Islam, or Christianity.

Who are American Buddhists? That question can be answered, but only quite generally. On the one hand, there is no Buddhist “type” in America. Buddhists come from a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds, and there are white collar Buddhists; Buddhist cab drivers, mechanics, and chefs; and Buddhist artists and musicians. Some Americans are highly self-conscious about being Buddhist, while others take the fact that they are Buddhist for granted. At the outset, it should be assumed that there are many different kinds of Americans who, in one way or another, identify themselves as Buddhist.

On the other hand, there are at least three broadly defined groups within American Buddhism. One group consists of a mixed bag of native-born Americans who, over the course of the last fifty or so years, have embraced the teachings of the Buddha. They are part of a broad movement that had its origins in the 1940s and ’50s, took off in the 1960s, and then continued to gain momentum through the end of the century. They are often referred to as western or European American Buddhists, but they include Asian, African, and Native Americans. I will generally refer to them as convert Buddhists to distinguish them from other Americans, mostly from Asian backgrounds, who were raised and educated in Buddhist communities. By convert I mean not so much a person who has embraced an entire religious system, but, in keeping with the original meaning of the term, someone who has turned their heart and mind toward a set of religious teachings, in this case the teachings of the Buddha.

A second group is composed of immigrant and refugee Buddhists from a range of Asian nations who are in the process of transplanting and adapting their received traditions to this country. This development is also linked to the 1960s; legislative reforms passed in Washington in 1965 made possible a dramatic increase in the number of immigrants arriving from Asia. Most American Buddhists are in the nation’s Asian communities, and they are generally referred to as immigrant or ethnic Buddhists to distinguish them from converts. But for well over fifty years, Buddhist immigrants taught native-born Americans, and many of the founders of convert Buddhist communities were Asian immigrants.

A third group is composed of Asian Americans, primarily from Chinese and Japanese backgrounds, who have practiced Buddhism in this country for four or five generations. The most well-known institutional form of religion in this group is the Buddhist Churches of America, Japanese Jodo Shinshu Buddhism. As a group, BCA Buddhists do not share with converts the heady sense that comes from having discovered the teachings of the Buddha only recently. Nor are they preoccupied with building the foundations of their community, as are recent immigrants and refugees. They are America’s old-line Buddhists who, in the landscape of late twentieth-century Buddhism, were neither fish nor fowl, neither convert nor immigrant.

During the last decades of the twentieth century, converts and immigrants have held center stage in American Buddhism, and they have given the dharma in this country much of its vibrancy and complexity. But their approaches to adapting Asian traditions differ radically due to the nature of their relationship to Buddhism and their location in American society. Many converts first discovered Buddhism in books. Some then traveled to Asia to learn more about it, while others set out to find Buddhist teachers in America, something that only three or four decades ago was not easy to do. By the 1980s, convert Buddhists began to speak in their own voices when a generation of native-born Americans moved into prominence as scholars, dharma teachers, and community leaders. At about that time, converts began to explore in earnest ways to create indigenous forms of the dharma suited to those born and bred in the cultural mainstream of the United States.

During these same years, immigrant Buddhists were also creating forms of the dharma suited to America, but out of a different social location. Like Jews and Catholics a century or two before, they approached developing forms of American Buddhism as part of the immigrant experience, in which questions about adapting religion to America were intimately related to a broad range of economic, cultural, and linguistic issues. The first generation needed to find work, re-create their traditional religious life, and explain their religion to their rapidly Americanizing children. The long-term contribution of immigrants to Buddhism in America is very hard to assess, because the nature of the immigrant experience is such that adaptation occurs only over the course of several generations.

A few statistics on American Buddhism are available, but they vary considerably. One source put the total number of practicing Buddhists at a round one million in 1990, but another at 5 or 6 million only a few years later. A more recent estimate must be considered rough, but appears to be the best available. Martin Baumann of Germany suggested in 1997 that there were 3 or 4 million Buddhists in the United States, the most in any western country. In contrast, he estimated that there were 650,000 Buddhists in France and 180,000 Buddhists in Great Britain. His estimates also suggest that converts consistently are outnumbered by immigrants. In the same year, France had roughly 150,000 converts and 500,000 immigrants, Great Britain 50,000 and 130,000 respectively. In the United States, he estimated there were 800,000 converts and between 2.2 and 3.2 million Buddhists in immigrant communities.4

These figures, however, need to be treated with caution. In the same year, 1997, Time magazine suggested there were “some 100,000” American Buddhist converts. It did not even venture to estimate the number of Buddhist immigrants.5 As a result, we must proceed without definite information regarding the actual number of American Buddhists. Suffice it to say, there are a great many and, more important, they are engaged in practicing the dharma in a wide variety of fascinating ways.