The Buddhist Churches of America (BCA) is the oldest major institutional form of Buddhism in the United States. Its Japanese American members are among the nation’s Buddhist pioneers, who have the most experience with the challenges involved in creating American forms of the dharma. For over a century, BCA Buddhists followed classic patterns of religious adaptation by immigrants. They brought received philosophies, institutions, ritual practices, and customs to the New World, where they selectively retained, abandoned, and adjusted them to make them work in a new culture. As was the case among Catholics and Jews, their course was determined largely by trial and error and was driven by perennial forces such as Anglicization, generational change, and the gradual movement up from the margins of society into the middle-class mainstream.

However, there have been important variables at work in their version of the immigrant saga, related to Buddhist history in Japan, Americans’ preoccupation with race, and long-standing tensions in Japanese-American international relations. The name Buddhist Churches of America was suggested during World War II by Japanese Americans in an internment camp in Topaz, Utah. It was adopted shortly thereafter at a conference in Salt Lake City, in an effort to blunt associations with America’s wartime enemy across the Pacific and to emphasize the institution’s Americanness. There was no Buddhist vogue in this country during World War II; that would only come later. Nor was there much of a precedent for being both Buddhist and American.

The Buddhism of the BCA is part of a broad stream of Pure Land doctrine and practice that runs from India throughout China, Vietnam, and Korea to Japan, where it is called Shin Buddhism. There it became a discrete movement in the thirteenth century, and subsequently one of the most popular forms of Japanese Buddhism. The BCA is in a specific school of Pure Land founded by Shinran and known as Jodo Shinshu, the True Pure Land School. More particularly, it is a branch of Nishi Hongwanji, the Western School of the Original Vow, a form of Jodo Shinshu that was prevalent in the region of Japan from which many Japanese Americans originally migrated. For about fifty years it was called the Buddhist Mission to North America (BMNA), a name that reflected both its status as subordinate to its headquarters in Kyoto and its original missionary character.

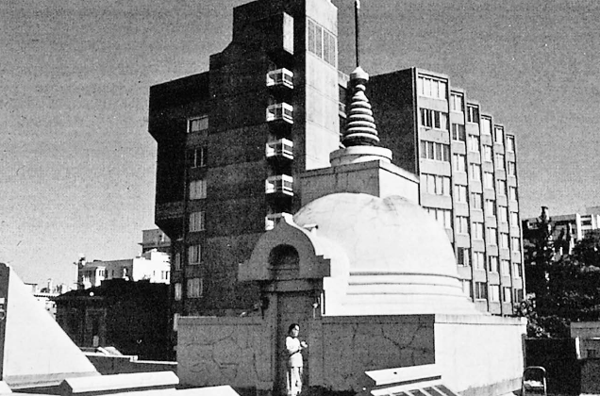

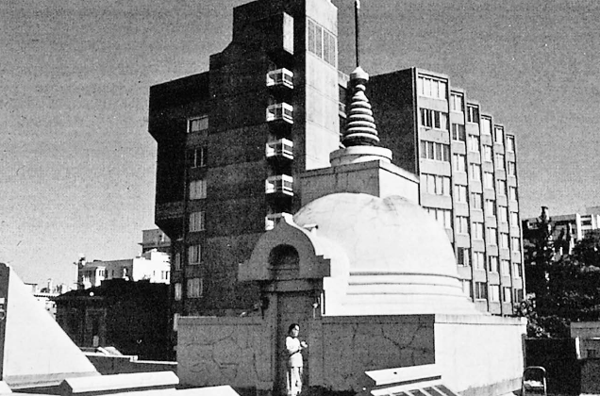

As the oldest major institutionalized form of American Buddhism, the BCA has been a pioneer in transplanting and adapting the dharma to the culture and society of the United States. This stupa, a devotional reliquary mound, is located on the roof of BCA head-quarters in San Francisco and is reputed to be the oldest of the many stupas now found in America.

THE PLURALISM PROJECT AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY

The members of the BCA are America’s old-line, ethnic Buddhists, but they do not comprise a large community. One estimate placed BCA membership at roughly 20,000 adults in 1996. Nor do they wield a great deal of influence in the broader American Buddhist community. They are, however, seasoned veterans of the American experience and have negotiated many of the pitfalls in the process of assimilation for over a century. They not only have paid a high price for being Japanese but also have had to articulate and defend their distinct brand of Pure Land Buddhism, which has been easily and often confused with Christian theism. In the current landscape of American Buddhism, they are in between categories, neither convert nor immigrant. But their sensitivity to the issues involved in the Americanization of the dharma may, in the long term, enable them to help broker relations between the two much larger groups that currently dominate discussions about the future of Buddhism in the United States.

A Century of Adaptation

The history of the BCA has been largely shaped by a long-term conflict between Japanese and American national interests. The origins of American Jodo Shinshu can be traced to the 1870s, when Japanese began to arrive on the West Coast, where they often worked as agricultural laborers. At this early date, most immigrants assumed they would return to Japan, so transplanting their religious and cultural traditions was not an issue. But by 1900, the community had grown to over 24,000, a substantial enough number to warrant establishing the Buddhist Mission to North America. At about this time, Pure Land, Nichiren, and Zen Buddhism were also being introduced to the United States at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago. The two developments are not wholly unrelated; both Japanese immigration and the Parliament were a part of a larger sequence of events as Japan and the United States explored each other and their political, economic, and military interests in the Pacific basin. Eventually, American Jodo Shinshu Buddhists would be caught between the two countries.

Hindsight reveals perennial tensions in BCA history, dating back to small events of the first year it began to set down roots in this country. The first missionary priests arrived in San Francisco to serve the Japanese community in 1898, the same year the United States went to war with Spain and annexed Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, an inauspicious conjunction of events that would lead to a wartime disaster for the community in the middle of the next century. There was also a hint of how religious innovation and traditionalism would both come to play a role in the community. During their brief stay, these priests founded a Bukkyo Seinen Kai, a Young Men’s Buddhist Association (YMBA), an innovative form of lay Buddhist organization inspired by Christian institutions in Japan. The following year, the first Hanamatsuri and Gotan-E ceremonies, honoring the birthdays of the Buddha and Shinran respectively, were held in the community. YMBA members soon sent a formal petition to the Kyoto headquarters of Nishi Hongwanji to request the posting of a permanent missionary in America, a move the Japanese consul to the United States disapproved of as politically imprudent and potentially inflammatory.

The formal history of the BCA is usually dated from 1899 and the arrival of the first permanent Jodo Shinshu missionaries, Shuye Sonoda and Kakuryo Nishijima. The following decades were marked by the kind of institution building normally undertaken by the pioneering generation in an immigrant community. Young Men’s Buddhist Associations and temples were founded along the West Coast from Seattle to San Diego. A newsletter was established to facilitate communications between isolated communities, many of which were located in rural, agricultural areas. The Fujinkai, or Buddhist Women’s Association, was established, and would subsequently play an important role in the development of Jodo Shinshu. Throughout this period, BMNA religious activities were conducted primarily in Japanese.

In the early 1900s, the first anti-Japanese agitation gripped the West Coast, resulting in attacks on Japanese businesses and buildings and the formation of the Asiatic Exclusion League, based in San Francisco, in 1905. This agitation resulted in the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, legislation that restricted immigration to the wives and children of Japanese men already residing in this country. On one hand, this limited the growth of the BMNA. On the other, it fostered the emergence of stable, family-oriented Japanese communities in which the Jodo Shinshu temples came to play an increasingly important part. Unlike in Japan, temples in America became the site of a wide range of religious and social functions—bazaars, dance parties, baseball games, and movies; funerals, weddings, memorial ceremonies, and Sunday services. In rural areas, temples became especially strong because they had a virtual monopoly on the social life of the community.

During this period, relations were also normalized with the Nishi Hongwanji temple in Kyoto. The leader of the BMNA was first called a kantoku, or director, but in 1918 was elevated to socho, a chancellor or bishop, and headquartered in the San Francisco temple. By 1914, the BMNA had constructed a new building from which the socho directed an institution with about twenty-five branches and temples. Until World War II, these North American institutions remained under the spiritual direction of the Monshu, the abbot of Nishi Hongwanji, who by tradition was always selected from among the direct descendants of Shinran. The more routine management was carried out by various Kyoto legislative and administrative bodies. Despite continuing anti-Asian sentiments, the BMNA was sufficiently confident to host a World Buddhist Conference in 1915 at the Panama Canal Exposition in San Francisco, during which BMNA leaders decided to create missionary programs for youth and to open Sunday schools, and began to draft a formal constitution.

The BMNA entered another phase around 1920, which continued up to the start of World War II. It was marked by increasing anti-Japanese and anti-Buddhist pressure from the dominant society and, with the coming of age of Japanese American youth, the emergence of second-generation issues.

State and national legal initiatives began to effectively isolate Japanese Americans several decades before their wartime internment. In the early 1920s, with increased concerns about the influence of Japan in the Pacific, a number of western states passed alien land laws aimed at limiting Japanese ownership of property. In 1922, the Supreme Court reviewed a long-standing case that bore on naturalization, ruling that American citizenship was a privilege reserved for “free white Americans” and people of African descent. The Oriental Exclusion Act was passed in 1924. It included a provision that no Japanese who were not already citizens or who had not been born in the United States would be granted citizenship. Immigration quotas were subsequently set that overwhelmingly favored Europeans.

As a consequence of these legal initiatives, Japanese often encountered difficulty securing land for new temples. Sometimes Caucasian Christians aided them, but at other times blocked them by whipping up local anti-Japanese sentiments. In the 1920s, a number of Japanese religious groups in Los Angeles, both Buddhist and Christian, were prevented from founding new temples and churches.

The unjust nature of this legislation actually helped to increase the number of American Buddhists. Many Japanese Americans had been hesitant to identify themselves as Buddhist, but exclusion encouraged them to band together for welfare and security. As a result, the temple also became increasingly important, as the headquarters for a range of social and cultural services from Japanese-language schools to rotating credit systems, and as a center in which continuity with Japanese culture could be maintained. Many Caucasians viewed this inward turn on the part of the Japanese as evidence of chauvinism, but the temples actually served as vehicles for Americanization by sponsoring athletic leagues, Boy Scout troops, and American-style dances. This double function of the religious center—providing both cultural and religious continuity and mechanisms for adaptation and change—is a phenomenon also found in Jewish and Catholic immigration history.

This period also marked the beginning of a rift between the first, immigrant generation, the Issei, and the second, American-born generation, the Nisei, a type of generation gap unique to immigrant communities. Anglicization is a primary second-generation issue, and the way in which it is resolved has a long-term impact on the religious life of a community. The Japanese language was used by the Issei and BMNA ministers, and it structured the religious life of the entire community well into the 1920s. Questions about how to translate Jodo Shinshu doctrine and practice into English surfaced in 1926, when the BMNA began to train Nisei as instructors for its Sunday schools. As the numbers and importance of the Nisei grew over the next decades, it became necessary to selectively retain, translate, and abandon religious language that had long played a central role in defining the community. In the short term, changes made in religious language posed a threat of unintended Christianization. In the long term, however, they helped to create a fluid vocabulary, part Japanese, part English, that continues today to give a distinct ethnic and religious character to the Jodo Shinshu community.

Anglicization gave what some have seen as a Protestant cast to the Jodo Shinshu religious worldview. Socho became “bishop,” gatha “hymn,” and kaikyoshi or jushoku, “minister.” Bukkyokai and otera were translated as “church” or “temple,” dana as “gift,” and sangha as “brotherhood of Buddhists.” Countervailing trends also emerged. Terms associated with religious service—shoko, the offering of incense; juzu or nenju, rosarylike beads; and koromo, the robe worn by the priest—were retained. Complex abstract and historical terms—karma, nirvana, Mahayana, and Hinayana—gained expression in Anglicized forms of ancient Indian Sanskrit. At the same time, other ancient south Asian terminology that began to come into vogue among early convert Buddhists, such as the use of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis to describe individuals committed to the dharma, were rejected as alien to the religious spirit of a Japanese lay community.

More fundamental institutional shifts underway also were expressed in the shifting use of language. There were varied ministerial ranks in the Nishi Hongwanji sect in Japan—tokudo, soryo, jushoku, kyoshi, fukyoshi, and others—that reflected degrees of formal education, residential status, and level of ordination and certification. All the nuances of office conveyed by such terms vanished when translated into rough English equivalents, “priest,” “minister,” or “reverend.” Similar shifts had consequences on a highly practical level. Most Jodo Shinshu temples in Japan are owned by families and are passed on to eldest sons on a hereditary basis. In contrast, Jodo Shinshu ministers in the United States became personnel hired by the BMNA to serve congregations.

Despite the BMNA’s strong move toward Americanization, many Nisei began to drift away from Buddhism, without necessarily converting to Christianity. At the same time, Issei began to recognize the permanent character of their stay in the United States. The older generation did not necessarily feel at home or at ease in America, which had often given them little reason to do so. But their commitment to the new country had become manifest in their work, their emotional ties with other Japanese Americans, and in the lives of their Nisei children who had become thoroughly American.

This situation was radically altered at the onset of World War II. The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 resulted in an immediate roundup of Issei businessmen, religious and community leaders, and martial-arts teachers. Despite formal statements of loyalty issued by BMNA leadership, the Federal Bureau of Investigation began to investigate all Japanese Americans, but especially those in the Buddhist community. For most of the summer of 1942, the community was under suspicion, which led many BMNA members to burn sutras and conceal family altars. In February of 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which designated the West Coast as a military district from which all alien Germans, Italians, and persons of Japanese ancestry were to be removed. Subsequently, 111,170 Japanese—Buddhist, Catholic, and Protestant—were interned in about a dozen camps located in several states across the nation. Of these, 61,719 were Buddhist, the majority of them Jodo Shinshu.

The internment camps accelerated both the processes of Anglicization and Americanization and the emergence of the Nisei as the leaders of the Jodo Shinshu community. For a time, religious services in the camps were required to be in English, which marked the beginning of the use of the English language in worship. People from a range of Buddhist traditions also found themselves interned together, which fostered the growth of an ecumenical dimension within the larger Japanese American Buddhist community. Nyogen Senzaki, the Zen pioneer who led his floating zendos in San Francisco and Los Angeles, left a poetic record of this defining moment in American Buddhist history. “Thus I have heard,” begins one poem written in 1942, echoing the opening lines of many a Mahayana sutra, “The army ordered / All Japanese faces to be evacuated / from the city of Los Angeles.” Other poems convey a sense of the collective religious life of Buddhists in camps such as Heart Mountain, Wyoming, where Senzaki was interned.

An evacuee artist carved the statue of baby Buddha.

Each of us pours the perfumed warm water

Over the head of the newly born Buddha.

The cold spell may come to an end after this.

A few grasses try to raise their heads in the tardy spring,

While the mountain peaks put on and off

Their veils of white cloud.

Or again:

Sons and daughters of the Sun are interned

In a desert plateau, an outskirt of Heart Mountain,

Which they rendered the Mountain of Compassion or Loving-Kindness.

They made paper flowers to celebrate Vesak, the birthday of the Buddha.1

Internment also pushed Nisei ministers, of whom there were only four at the time, to the forefront of the community, due to their ability to negotiate with authorities in English. Nisei also rose to prominence as a result of a questionnaire issued by the War Relocation Authority in 1943 in an attempt to determine Japanese American loyalties. Two questions in particular served to drive a wedge between the Issei and Nisei, one about the willingness of those interned to serve in the United States armed forces, the other about renouncing all allegiances to Japan. These questions posed few problems for Nisei, who were native-born, English-speaking, American citizens. But for Issei, who were legally excluded from citizenship, they proved more problematic. Those Issei who answered no were considered high risk by the government. They were isolated together in a camp at Tule Lake, California. Those who answered yes to both questions were moved elsewhere and eventually granted early release if they did not return to the West Coast, a development that led to the establishment of temples in the east.

The camps also played a decisive role in reshaping and Americanizing the Jodo Shinshu institutions. Ministers met in February of 1944 at the camp in Topaz, Utah, where Ryotai Matsukage, the current socho, was interned. There they first proposed to change their name to Buddhist Churches of America. Later the same year, they voted to reincorporate as the BCA, repudiate all ties to Japan, redefine their relation to Nishi Hongwanji in Kyoto, and redesign the organizational structure of the BCA to shift more power to the Nisei. They also made the position of BCA bishop an elective office.

The history of the BCA after the war is a Japanese American and Buddhist version of the return to normalcy. Temples that had been closed during the war needed to be reopened. Businesses had to be rebuilt and wartime financial reversals overcome. New temples in the east founded by those released early from the camps had to be integrated into the institutional life of the BCA. Soon the Sansei, or third generation, began to come of age in postwar America.

This period of reconstruction came to an end in 1966 with the founding of the Institute of Buddhist Studies (IBS) in Berkeley, California, an event that is often cited as the symbolic culmination of earlier Americanizing tendencies. BCA ministerial candidates, who previously had gone to Kyoto for Japanese language-based religious education, were now able to receive English-language education in their native land. New Issei candidates, who continued to play an important role in the BCA, were expected to arrive in this country with English fluency and to attend IBS for intensive study and training. In 1968, a Canadian-born Nisei was selected as bishop and, for the first time in the history of American Jodo Shinshu, the inaugural ceremony was held not at Nishi Hongwanji in Kyoto but in the United States.

Mainstreaming Jodo Shinshu

Despite the trauma and humiliation of internment, the Japanese Americans in the BCA emerged in the 1960s as a small, ethnically and religiously distinct minority group that was part of the broader American middle class. With renewed confidence, they began to play a role in political and religious debates in the secular arena. The BCA was influential in California debates over public-school curricula during the 1980s and ’90s, which tested the strength of the nation’s commitment to multicultural education.

The BCA Ministerial Research Committee also helped to successfully challenge the use of a grade-school textbook that contained racial stereotypes about Japanese Americans and displayed a pro-Christian, anti-Buddhist bias. The BCA publicly adopted a strong “wall of separation” position against the teaching of creationism and prayer in the public schools and thus joined in a long tradition of appeals to the Constitution by ethnic and religious minorities. Its position, however, contains a Buddhist twist, as evidenced in several key paragraphs in a document entitled “BCA Resolution Opposing the School Prayer Amendment.”

Whereas, Prayer, the key religion component [of the amendment], is not applicable in Jodo Shin Buddhism which does not prescribe to a Supreme Being or God (as defined in the Judeo-Christian tradition) to petition or solicit; and

Whereas, Allowing any form of prayer in schools and public institutions would create a state sanction of a type of religion which believes in prayer and “The Supreme Being,” would have the effect of establishing a national religion and, therefore, would be an assault of religious freedom of Buddhists;

Resolved, That the Buddhist Churches of America and its members strongly oppose any form of organized prayer or other religious observances in public schools and public institutions, which are organized, supervised, or sanctioned by any public entity, except as permitted by the current constitutional law.2

These efforts reflect the sensitivity of the leaders of the BCA to the kind of pressures they had experienced in this country over the course of a century as both a racial and a religious minority group. Minority immigrant communities face special challenges because the ideas, customary modes of thought, and even sentiments of the dominant group take on a normative character in any society and exert a great deal of pressure, both subtle and gross, on all immigrants. The ways in which they both conform and resist conformity give a unique dynamism to the religious life of the community.

Some outside pressures brought to bear upon Japanese Americans in the BCA have been extraordinary—racism, the rising competition between the United States and Japan, World War II, and the internment camps. But much subtler forces have also been at work in the past and still are today, from norms of decorum to the theistic religious ideas presumed by most Americans.

Two examples illustrate the intimate ways in which the sensibilities of the dominant culture affected Jodo Shinshu Buddhists in subtle but concrete ways. The first is drawn from an interview conducted with an Issei kaikyoshi (a distinct type of Japanese missionary minister) in the early 1970s, reproduced here with the definitions and clarification of the interviewer.3

INT: What is the difference between Issei Buddhism and Nisei Buddhism, and then Sansei Buddhism?

RESP: That definition would be based on majority membership, and so, of course, [on the] accompanying psychological or other cultural differences.

INT: But are they all Buddhists?

RESP: All Buddhists, yes.

INT: Now, is Jodo Shinshu Buddhism different between the Issei, Nisei, and Sansei?

RESP: I don’t think so, and the doctrine, of course, never changes. Buddhism you know consists of the triple jewels: [the Buddha], the teachings of the Buddha, and the Sangha [brotherhood of Buddhists].… The Sangha may be changing. Even the vocabularies must be carefully used. This is a funny example, but the lady’s breast is a symbol of mother’s love in Japan. So we often refer to Ochichi o nomaseru [literally: to allow someone to drink from the breast], but some Issei ministers came to this country and explained [this concept] pointing [to the breast region] causing laughter among the [non-Japanese speaking] audience. So we have to adapt ourselves to this particular situation even linguistically. So from that standpoint, maybe our way of presentation must be changed.

INT: But not the doctrine.

RESP: Not the doctrine.

A second example comes from “The Point of Being Buddhist, Christian or Whatever in America,” an article by Evelyn Yoshimura first published in 1995 in Rafu Shimpo, the oldest and largest Japanese American daily newspaper in the United States.4 But it soon found its way into Hou-o: Dharma Rain, the online community newsletter of the Vista Buddhist Temple in southern California. The article is about how peer pressure from Christian friends can have an impact on teenage Buddhists.

One part is devoted to recounting events that took place at a local Baptist church sponsoring Friday-night socials for area youth. Buddhist teenagers in attendance found themselves confronted with an inspirational talk that reiterated simplistic and, for many people in Christian circles, old-fashioned ideas about Buddhism. Christianity was promoted as the only true religion, while Buddhism was characterized as the “‘worship of suffering’ and the quick ticket to hell.” Some Baptist children later began to aggressively evangelize Buddhist students at school. This religious zeal, Yoshimura noted, was experienced by Buddhists as “the pressure to ‘fit in.’” Some Buddhist teenagers reportedly converted to Protestantism. A second part of the story was about a Buddhist girl who had hosted a party at her home, where she was cornered by Christian students who urged her to convert. She was so angry and upset that she left her own party.

The upshot of all this, however, was that a number of Buddhist children began to explore the Buddhist tradition more deeply. As Yoshimura recounts it:

The Buddhist kids began talking to each other and their parents and other temple adults about this pressure they were feeling. And during the course of these discussions, they realized that Buddhism is harder to explain than Christianity because there’s a lot of ambiguity, and it’s not based on “belief.” Rather, it focused on seeking the “truth” and trying to be honest with others and especially yourself. There is no supreme being. No soul. Only actions [karma] and what remains from them. Hard to explain in 25 words-or-less.

Yoshimura went on to report that teenagers from temples in other areas in southern California subsequently participated in a Saturday-night Buddhist discussion group.

The temples of the BCA have long served both as religious organizations and as cultural centers in which traditional language and folkways can be maintained as a vital part of community life. Taiko, a form of ceremonial drumming, is practiced by young people in many Jodo Shinshu temples, as at Senshin Buddhist temple in Los Angeles, pictured here.

THE PLURALISM PROJECT AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY

Given its century of experience, the BCA now approaches such pressures with both confidence and self-consciousness. Renewed attention is being paid to the priorities and sensibilities of the youngest generations, those who are now the third, fourth (Yonsei), or even the fifth (Gosei) in line from the founding one. Sectarian doctrine and traditionalism remain important in American Jodo Shinshu, but the BCA is by no means monolithic. BCA leaders advocate renewal of a dharma-centered church, temple, or sangha, in a range of conservative and progressive modes. Others emphasize the cultural dimensions of the life of the temple and the importance of the Japanese language to the maintenance of religious sentiments and ethnic identity.

As is often the case in the histories of American immigrant communities, there is a movement in the third and subsequent generations to return to tradition. Masao Kodani, a prominent Sansei minister in Los Angeles, wrote in the mid-1990s that a “renewed emphasis on traditional ritual allowed many Jodo Shinshu Buddhist temples to remove many of the Congregational Christian elements of service worship that found their way into the Sunday service, while maintaining the ‘Sunday go to meeting’ custom of American religion.”5 This also meant that temple-sponsored basketball leagues, an important element in contemporary temple life, flourished side by side with Japanese cultural traditions such as taiko (folk drumming), Bon Odori (an annual ceremonial dance), and Mochi-tsuki (the making of rice cakes).

There was, however, a downside to the mainstreaming of the BCA. Like the mainstream Protestant churches, it has problems such as institutional inertia, financial shortfalls, and declining membership. Like ethnic Jews and Catholics, BCA members discovered that their arrival in the mainstream often resulted in the loss of ethnic and religious identity. Declining membership, together with a high rate of outmarriage, has encouraged renewed attention to adult education and to developing international exchanges with Japanese Jodo Shinshu and other Pure Land groups. At the same time, some temples and study groups have attracted more non-Japanese, who despite their long presence as both members and ministers in the BCA have always formed a very small percentage of the total community. One minister has included zazen groups in the temples he leads, a move that conservatives consider controversial for doctrinal reasons that will be considered shortly. A number of Jodo Shinshu leaders have also worked to set up lines of communication among converts and new immigrants within the broader American Buddhist community.

American Jodo Shinshu Practice and Worldview

Most American convert Buddhists identify the dharma with sitting meditation, tend to dismiss Jodo Shinshu as a form of lay devotional Buddhism, and have little understanding of its traditions. But over the course of four or five generations, Jodo Shinshu has been Anglicized, modernized, and adapted to the culture of the United States. Despite its minority status in the Buddhist community today, the BCA is in the forefront of Americanization. Pure Land Buddhism is, moreover, one of the most popular dharma traditions in Japan and it is of major importance in other Asian American Buddhist communities, most prominently the Vietnamese and Chinese. Thus, while the BCA is itself a small and distinctive sect outside the ken of most converts, its philosophy, doctrine, and practice resonate with the traditions of other immigrant communities.

The Pure Land

Jodo Shinshu means literally the “True” (Shin) “School” (shu) of the “Pure Land” (Jodo). For many centuries, Pure Land practice in east Asia took the form of chants, visualizations, and vows, many of which are still used in Chinese Buddhism. They have been used to gain a temporary rebirth in the Pure Land, which is thought to provide an ideal environment in which to prepare for the attainment of enlightenment in another life. Ancient sutra literature describes the Pure Land in lavish language meant to convey its transcendental nature—golden trees, jeweled terraces, delightful music, scented winds, and beautiful birds whose singing calls to mind the Buddha, dharma, and sangha. The Pure Land is an environment wholly designed to foster one’s ability to ultimately achieve liberation.

Over the centuries, many Buddhists have thought of the Pure Land as a distinct, otherworldly location, and many westerners have likened it to popular ideas of Christian heaven. But other interpreters have long understood the Pure Land to be more a transcendent state of being than a location. Ancient sutras portray the Buddha as passing into samadhi, a deep trance state, before he preached on the Pure Land, which suggests it is best understood as a reflection of his awakened consciousness. His descriptions of the Pure Land are often considered an expression of the Buddha’s skill in using symbols to communicate with unenlightened beings. Today some Jodo Shinshu Buddhists describe the Pure Land as a liberating realm into which one passes after death, later returning to the world of samsara to carry on the bodhisattva’s task of helping all beings achieve enlightenment. Others talk of it more as a sense of joy, peace, and delight experienced within the conflicts and contradictions of this life.

Amida

Amida Buddha has often been understood by non-Buddhists to be a direct parallel to the western idea of a personal God. Some American Jodo Shinshu Buddhists have been known to equate the two—one result of the linguistic pitfalls that have come with Anglicization. In some forms of Buddhism there are many gods, but Amida is not one of them. He is rather among the greatest of the cosmic buddhas of the Mahayana tradition.

As told in the sutra literature, Amida was originally a man named Dharmakara who renounced the world and set out to attain enlightenment. After meditating for many ages, he announced his intention to create the most perfect Pure Land, the character of which he described in forty-eight vows. By fulfilling these vows through rigorous devotion and practice, he eventually became a fully realized buddha. From the great storehouse of merit he accumulated, he created the Pure Land, where he took up residence as Amida. Amida means infinite life and light, and connotes the boundless wisdom and compassion of all the buddhas and bodhisattvas.

This story has inspired philosophical reflection and undergone doctrinal elaboration over the centuries. Since the time of Shinran, the Jodo Shinshu tradition has emphasized Dharmakara’s vows, particularly the eighteenth. In this vow, Dharmakara stated that he would forego total liberation if rebirth into his Pure Land lay beyond the reach of people “who sincerely and joyfully entrust themselves to me, desire to be born in my land, and contemplate on my name even as many as ten times.”6 Because Dharmakara eventually gained liberation and took up residence in the Pure Land, this vow is taken to mean that all can enter there by calling on Amida.

Amida is somewhat like the Christian God insofar as they are both considered to be other than mere humans. God and Amida are also both considered the source of love and mercy. Jodo Shinshu is a tariki or “other power” path, in contrast to paths characterized by the term jiriki, which means “one’s own efforts.” In this context, “other power” means that realization comes through the power and grace of Amida. Practices such as zazen are considered to be jiriki, and it is a point of Jodo Shinshu doctrine that all such paths are fruitless activities. Unlike the Christian God, however, Amida is not understood to be an omnipotent creator, judge, and law-giver. Nor is Amida considered a being distinct from the created universe. He is rather a manifestation of “oneness” or “suchness,” terms used in the Mahayana tradition to denote the Buddha nature (or mind) innate in the universe.

Shinjin

Shinjin is often translated as “faith,” but is also used without translation, such as in the phrase “shinjin consciousness.” It refers to a spiritual transformation that takes place within this life, which simultaneously involves understanding, awareness, and insight. It is an awakening to an entirely new mode of being in the world, becoming aware of one’s own limited human nature and the oneness of all being. This transformation is brought about not by self-initiated acts such as rituals or zazen, but through the grace and compassion, the other power, of Amida. Shinran equated shinjin with the initial state of enlightenment referred to by Theravada Buddhists as that of “the stream-winner,” who has not overcome all defilements but can be assured of eventually attaining total liberation. Shinjin also implies insight into Mahayana teachings about the interdependence and interconnectedness of all things in the universe. Jodo Shinshu Buddhists understand the transformative power of shinjin as resting on the merit of the vows fulfilled by Dharmakara and bestowed on people by Amida.

Nembutsu

The term Nembutsu refers to the phrase Namo Amida Butsu, or “Name of Amida Buddha,” which plays a particularly important role in Jodo Shinshu Buddhism. As a chant or recitation, the phrase has a long history of use in Pure Land Buddhist traditions, but it was elevated to its central position in Japanese Pure Land schools in about the twelfth century. One Japanese reformer, Honen, emphasized the oral repetition of the Nembutsu as a way to attain rebirth in the Pure Land. Shinran, who was his disciple, recast his understanding of the phrase in a small but important way. He taught that the Nembutsu should be chanted not to attain the Pure Land, but out of thanks to Amida for already having granted one entrance into it. By doing this, Shinran moved the other power of Amida into the foreground of Pure Land philosophy.

In Jodo Shinshu, the Nembutsu is understood to be an expression of joy and gratitude to Amida, a call to him naturally arising from shinjin consciousness. On a more modern and colloquial level, chanting the Nembutsu is a way to entrust oneself to Amida, who will buoy one up in the face of inner and outer turmoil and confusion. Jodo Shinshu Buddhists do not consider the Nembutsu a mantra to be used to evoke awakening or to invoke Amida, as a Vajrayana Buddhist might. Chanting mantras, like doing zazen, is a jiriki practice that Jodo Shinshu Buddhists consider ineffectual.

The importance of fine doctrinal considerations such as these should not obscure the fact that the religious life of the BCA is also rich in traditional ritual and ceremony—Hanamatsuri, the commemoration of Gautama’s birth; Gotan-E, Shinran’s birthday; and Jodo-E, the celebration of Buddha’s enlightenment. Home altars, which are used both to call Amida to mind and to honor ancestors, have long played an important role in Jodo Shinshu piety and still do today. Funerary rites and periodic memorial services for ancestors remain an integral part of BCA religious life, inherited from the many centuries in Japan during which Buddhism became associated with death and the next life. Forms of temple etiquette—gassho, a small bow made with hands pressed together as a sign of respect; the carrying of the juzu, a rosarylike string of beads used in chanting; the precise ways in which to burn incense on different occasions; the reception of a homyo, or dharma name—continue to influence Jodo Shinshu identity, sensibilities, and piety.

But despite the importance of tradition, doctrine, and ceremony, America’s Jodo Shinshu Buddhists are in many ways much like parish Christians. There are “bazaar Buddhists” who are rarely seen at temple services, but turn out to work at annual socials that are big events in the communal life of the BCA. There are “board Buddhists,” whose chief contribution to religious life is helping to administer the temple. There are also Buddhist “basketball moms,” who devote a good deal of their time to shuttling children in minivans from one temple activity to the next. The Fujinkai, or Buddhist Women’s Association, has been a mainstay of Jodo Shinshu since its earliest days, and in the past few decades women have also joined the ministerial ranks of the BCA.

However much Jodo Shinshu Buddhists may resemble many middle-class Christians in these and other regards, there are noteworthy differences. The BCA community has over its relatively long history in the United States negotiated ways to live in two worlds—a Buddhist world rooted in east Asia and a European American world shaped largely by western Christianity. In one of his writings, Masao Kodani of the Los Angeles Senshin temple notes that “the way in which we absorbed these two seemingly incompatible traditions, the Far Eastern and American, is what makes us unique. We are not Japanese as in Japan, we are not American as in apple pie, nor are we the best of both.” Most times BCA Buddhists move easily between these overlapping worlds “but with periodic moments of anguish when we try to resolve the contradictions.”7

Some of the anguished moments to which Kodani refers are undoubtedly related to religion. BCA Buddhists often criticize themselves for what they see as their passivity, their unwillingness to identify the pursuit of happiness as success, and their reluctance to engage in extroverted, American-style positive thinking. But Kodani sees these same traits as an introspective Buddhist value orientation that is to be cultivated and cherished. “The truth about ourselves is more important than positive self-image and positive-thinking. The joy of the dharma is because one has been moved to the truth of oneself, not because one gets what he wants. Getting what one wants is happiness, being guided to what is true is Joy. Happiness and Joy in this context are two unrelated words.”8

Kodani further developed this line of Buddhist religious thinking in Becoming the Buddha in L.A., a 1993 documentary produced by Boston’s WGBH Educational Foundation.9 His remarks reflect the confidence and collective wisdom of a religious and racial minority community that, over the course of a number of generations, negotiated its way from the margins to the American mainstream. “If you came from western Europe, you share a tradition,” Kodani told the interviewer, Diana Eck of Harvard University.

Ours is very much different. It is based on a very different view, that you do not press upon somebody else what fundamentally may not be real anyway—yourself, or your idea of who you are. If you come from a Buddhist tradition, a mature person is someone who learns to be quiet, not to speak out. Which is quite different from an American tradition. If you come from a Buddhist tradition, someone who says he knows who he is is rather suspect. A mature person is someone who says that he doesn’t know who he is.

Referring to an idea central to traditional Christianity and implicit in many Americans’ ideas about themselves, Kodani added that “our religion says that there is no such thing as a soul. Not only that, the impulse to believe in one is what causes suffering. This is fairly, radically different, I think, and it affects how you look at everything.”

In his view, however, such fundamental divergence of religious beliefs need not be a source of antagonism and conflict. “We need to understand, I think, that unity does not mean unanimity,” Kodani noted.

The Buddhist experience is based on this. Oneness does not mean agreement. It means everybody is different and that is the reason why we can get along.… I don’t think that it is true you have to agree—on pretty much anything—to get along. I mean if you don’t believe that there’s no such thing as a soul that doesn’t impinge on me. It doesn’t ruin my day, you know. Why should my insistence on a nonsoul ruin yours? Right? That position is very important for America because more than any other country, the whole world is here.

Largely due to its small size and its collective sense of decorum, the BCA is often overlooked in the current debates about immigrants, converts, and the future of Buddhism in the United States. But its members have paid substantial dues in the past, and have justly secured status as the trail-blazers of the American dharma. However the BCA negotiates its current challenges, Jodo Shinshu Buddhists share with a relatively small number of other Japanese and Chinese Americans the unique place of an old-line, middle-class Buddhist ethnic group in the American Buddhist mosaic currently in the making.