Soka Gakkai International-USA (SGI-USA) is the American branch of a worldwide Nichiren Buddhist movement that has its origins in Japan. For the past half century, its own unique path toward Americanization has been deeply influenced by tensions between a highly traditional Nichiren priesthood and the innovative spirit of the laity. During these decades, priests and laypeople together formed an organization called Nichiren Shoshu of America (NSA). But long-standing conflicts of interest between the two parties erupted in 1991 into a formal schism. Since then, the movement has split into two organizations, the smaller Nichiren Shoshu Temple (NST) led by the priesthood and Soka Gakkai International-USA, a much larger, wholly lay movement. The lay nature of SGI-USA, the energy its members displayed in the wake of the schism, and liberal elements it inherited from its prewar Japanese origins have helped to transform it into one of the most innovative forms of Buddhism on the current American landscape.

There are, however, other variables at work in Soka Gakkai that contribute to its uniqueness. Nichiren Shoshu of America first began to flourish in this country in the 1960s when many Americans embraced Asian religions, but was never as intimately identified with the counterculture as Zen. As SGI-USA, it is primarily a form of convert Buddhism, although there are in it many immigrants, from both Japan and elsewhere in Asia. Japanese immigrants, moreover, played a pivotal role in laying its foundations in this country. But as a result of its successful propagation in American cities, SGI-USA also has a larger proportion of African American and Hispanic American members than other convert Buddhist groups. Many people know that Tina Turner, the dynamic African American entertainer, is a Buddhist, but most do not understand that she is a Nichiren Buddhist, having embraced the dharma during the heyday of the NSA.

Nichiren is a uniquely Japanese form of Buddhism, named for the thirteenth-century reformer Nichiren, who gave shape to it as a distinct religion. Nichiren’s doctrine and practice, however, stand well within the broad Mahayana tradition that is dominant throughout east Asia. Like many other forms of Mahayana Buddhism, it takes its inspiration from the Lotus Sutra. Over the centuries, more than thirty Nichiren sects and movements arose in Japan, but Soka Gakkai’s most unique characteristics are rooted in mid-twentieth-century Japanese religious history.

SGI-USA currently claims between 100,000 and 300,000 members, the wide margin of error being partially attributable to the home-based nature of the movement. It is a well-organized institution, but many members freely move in and out at the grassroots. Soka Gakkai has little in common with Zen and other traditions embraced by other convert Buddhists, partly due to Nichiren doctrine, which in the past has tended to be strongly sectarian, and to the style of Nichiren proselytizing, which until recently was highly evangelistic. Attitudes among other convert Buddhists also play a part in this separation. Many of them see Nichiren Buddhists as too devotional in their orientation to practice and too prone to see the dharma as a vehicle for achieving material, as well as spiritual, well-being. They distrust Nichiren’s evangelical tendencies and assume its high degree of institutionalization implies authoritarianism. In some respects, however, the gulf that separates Zen and Nichiren Buddhists in this country is based on a mutual lack of understanding and reflects an antagonism between the two groups that has a long history in Japan.

SGI-USA has a highly articulated institutional structure, but the daily ritual of chanting in a home-based setting forms the foundation for members’ dharma practice. These people in a Los Angeles–area home are chanting before an altar that contains a gohonzon, a replica of a mandalalike scroll first inscribed by Nichiren in the thirteenth century.

SOKA GAKKAI INTERNATIONAL

Japanese Historical Background

Many of the underlying forces at work in the Americanization of Nichiren Buddhism today can be traced back to the progressive ideas of Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, the founder of Soka Gakkai. Makiguchi was born in 1871, into a poor family in a small village in northwestern Japan. Little is known about his early life, but by 1893, when he accepted a position as a supervising teacher in a primary school in Sapporo, his lifelong passion for progressive education had already taken shape. Japanese education was at the time highly regimented, having been designed to train loyal citizens to aid in the industrialization and modernization of Japan. But earlier in the century, Japanese intellectuals and educators had exhibited a great deal of interest in progressive and humanistic theories of education imported from the United States, England, and Germany. As a result of his teaching experience, Makiguchi became highly critical of the Japanese educational system and turned for inspiration to these progressive theories.

In 1901, Makiguchi moved to Tokyo where, despite his lack of university training, he hoped to publish in order to gain a scholarly reputation that would enable him to work for education reform. Despite well-received publications on Japanese cultural geography and folk societies, he remained outside the university establishment, working in a variety of editorial positions. In 1913, he returned to education as a primary-school principal in Tokyo. For the next two decades, he was a teacher and administrator in the Tokyo schools, during which time he gathered material for a four-volume collection, Soka Kyoikugaku Taikei (System of Value-Creating Pedagogy), published in the early 1930s, in which he developed his progressive educational theories.

Makiguchi’s theories are one foundation for Soka Gakkai International, and three different secular sources inspired his ideas about soka or value creation. One was cultural geography, a scholarly field that had a number of prominent Japanese interpreters around the turn of the century. Makiguchi drew upon their ideas about the reciprocal relation between culture and environment and its influence on the development of the individual. Another was the work of the American pragmatist John Dewey, who was widely hailed in the United States for his ideas about progressive education. The third source of inspiration was modern sociology, particularly the ideas of Lester Ward, from whom Makiguchi derived basic ideas related to values and their creation. Makiguchi envisioned an educational system in which the pursuit of individual happiness, personal gain, and a sense of social responsibility could all work together to foster the development of a harmonious community. The details of his ideas and the soundness of his theories are not important here. Some have dismissed him as a naive idealist, while others have praised him as a visionary.

Nichiren Buddhism became a second foundation for Soka Gakkai International in 1928, when Makiguchi joined Nichiren Shoshu or “The True Sect of Nichiren,” apparently sensing a need for a religious dimension to value-creation education. There was little evidence of the impact of religion on his ideas until 1937, when he published a pamphlet entitled “Practical Experimentation in Value-Creation Education Methods Through Science and Supreme Religion.” As its title suggests, he began about this time to explicitly link value creation to the Buddhism of Nichiren. The same year also saw the formation of Soka Kyoiku Gakkai (Value-Creation Education Society), the forerunner of today’s Soka Gakkai International, with Makiguchi as its first president. Until it was disbanded by the Japanese government in 1943, the Value-Creation Education Society grew increasingly preoccupied with religion. Kachi Sozo (The Creation of Value), the group’s monthly periodical, published Makiguchi’s ideas about value creation alongside testimonials from its members as to how Nichiren religious practices had brought them material and spiritual benefits.

In July 1943, Makiguchi and the entire leadership echelon of the Value-Creation Education Society were imprisoned. The Japanese government accused them of treason for their resistance to wartime efforts to consolidate Nichiren Shoshu with other Nichiren sects and for their militant opposition to State Shintoism. In November 1944, Makiguchi died of malnutrition in prison at the age of 73, having refused throughout his incarceration to recant his dual allegiance to the Value-Creation Education Society and Nichiren Buddhism.

The link between value creation and Nichiren Shoshu was strengthened in the postwar decades by Makiguchi’s successor, Josei Toda, a long-time aide and friend who was also incarcerated. In his cell in Sugamo prison, Toda chanted the daimoku, a central practice of Nichiren Buddhism, more than two million times, which became the basis for a powerful religious experience that subsequently informed his life’s work. After the war, Toda revived the movement under the name Soka Gakkai (Value-Creation Society), dropping the term kyoiku, “education,” which suggests how he would steer the organization away from secular concerns toward a more profoundly religious emphasis. As Toda worked to revive Soka Gakkai, he also became convinced that the movement had faltered in the prewar years because it lacked doctrinal clarity and discipline, so he began to teach the Lotus Sutra and the writings of Nichiren. Toda became the second president of Soka Gakkai in 1951. By his death in 1958, he had transformed it into one of postwar Japan’s most vital and vibrant new religious movements, claiming a membership of more than 750,000 families.

Toda’s success rested on his skill in implementing shakubuku, a form of proselytizing, preaching, and teaching long associated with Nichiren Buddhism, as a way to address the postwar social chaos in Japan, which he likened to the turmoil in Nichiren’s day. His religious vision was also informed by Nichiren’s idea of kosen-rufu, a term that connotes both the conversion of the world to true Buddhism and a utopian vision of world peace and harmony. Toda linked these practices and ideas to value creation in a way that gave meaning both to the personal lives of individuals and to their proselytizing activities. “You carry on shakubuku with conviction,” Toda told his followers in 1951. “If you don’t do it now, let me tell you, you will never be happy.”1 This kind of exhortation to evangelize in order to achieve personal happiness was central in Soka Gakkai in Japan throughout the 1950s, as it would be later in the United States. “Let me tell you why you must conduct shakubuku,” Toda told his followers in Japan.

This is not to make Soka Gakkai larger but for you to become happier.… There are many people in the world who are suffering from poverty and disease. The only way to make them really happy is to shakubuku them. You might say it is sufficient for you to pray at home, but unless you carry out shakubuku you will not receive any divine benefit. A believer who has forgotten shakubuku will receive no such benefit.2

Toda’s religious convictions played an immense role in shaping the movement, even as he unintentionally laid the groundwork for the later schism. Toda consolidated the institutional relationship between Soka Gakkai and Nichiren Shoshu, which under Makiguchi had proceeded on a more personal level. In 1951, he petitioned to have Soka Gakkai formally incorporated as a religious group. According to its charter, Soka Gakkai and its members became subject to the sacramental authority of the Nichiren priesthood, who were empowered to perform weddings, funerals, coming-of-age rites, and memorial services, and, most important, to issue the gohonzon, a religious scroll that is an essential element in Nichiren Shoshu worship. Soka Gakkai also took on the responsibility of registering its members at local Nichiren Shoshu temples and of observing the doctrines as defined by the traditions of the priesthood. Toda also made tozan, the pilgrimage to Taisekiji, the head Nichiren Shoshu temple near Mount Fuji, a central element in Soka Gakkai practice.

Toda’s linking of Makiguchi’s progressive ideals and Nichiren Shoshu institutions created an immensely effective, if inherently unstable, alliance, which resulted in periodic outbreaks of tension between the priesthood and laity. But it was left to Toda’s successor as Soka Gakkai president, Daisaku Ikeda, to oversee the tensions result in an outright schism.

Daisaku Ikeda, who is still president of Soka Gakkai International, is considered by many to be among the greatest modern Buddhist leaders, although he has his share of detractors and critics. He converted to Soka Gakkai in his late teens, and for a long time served as the Youth Division Chief. He was prominent in the shakubuku campaigns under Toda, who designated Ikeda as his successor. In 1960, Ikeda became president of Soka Gakkai and, through a succession of terms in office, he has remained the most powerful figure in the lay movement for almost forty years.

During this long tenure, Ikeda has reshaped Soka Gakkai into a more moderate and avowedly humanistic Buddhist movement through a process that seems to have been largely trial and error. From the start, he continued to emphasize the importance of shakubuku, although he gradually modified both the tone and techniques of proselytization. He recast the idea of kosen-rufu to mean the broad dissemination of, rather than the conversion of the world to, Nichiren Buddhism. During this time, Ikeda also transformed Soka Gakkai from a domestic new religion, a term generally used to refer to postwar religious movements in Japan, into a worldwide movement with national organizations on every continent.

Ikeda consistently praises Toda as his chief inspiration, but he also returned Soka Gakkai to Makiguchi’s emphasis on progressive education. In 1961, he created the Soka Gakkai Culture Bureau, with Economic, Speech, Education, and Art departments that foster value formation. He founded Soka High School in 1968 and Soka University in 1971, both of which are meant to showcase value-creation pedagogy. Ikeda led Soka Gakkai into politics in Japan with the founding in 1964 of Komeito, the “Clean Government Party.” Its electoral success led to widespread concerns about the influence of a new religious group on the government and about the violation of the postwar separation of church and state, which in 1970 led Soka Gakkai and the Komeito to legally separate. No comparable effort to directly connect religion and politics has been made in SGI-USA.

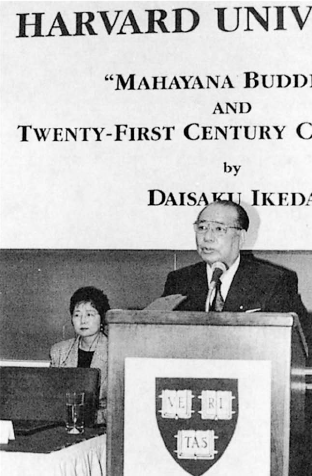

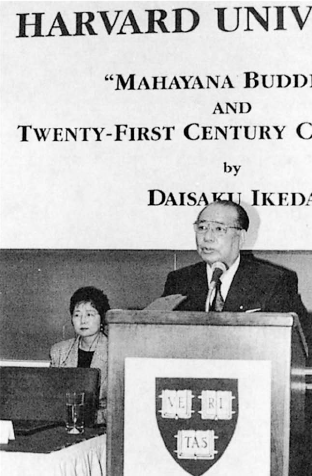

Under the leadership of Daisaku Ikeda, Soka Gakkai retained SGI’s religious foundations in Nichiren Buddhism while reemphasizing the humanistic ideas of its first president, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi. The dynamic leadership of Ikeda, shown here at Harvard University, helped to transform what had been a “new religion” in postwar Japan into a worldwide Buddhist movement.

SOKA GAKKAI INTERNATIONAL

Despite his deep commitment to the Lotus Sutra and Nichiren’s teachings, there is little doubt that Ikeda’s brilliance and success helped to precipitate the break between Soka Gakkai and Nichiren Shoshu. Ikeda has long been regarded by his followers as a great sensei or teacher. His charisma is such that many have likened him to a new Nichiren, which did not sit well with the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood. On a more fundamental level, however, the rupture occurred because the dynamic growth of Soka Gakkai simply began to outrun the authority, power, and imagination of the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood, particularly once Soka Gakkai began to flourish as an international movement.

Early Developments in the United States

The gradual changes in Soka Gakkai under Ikeda’s leadership are reflected in the evolution of the American movement. Shortly after his installation as its third president in 1960, Ikeda made his first trip to the United States, one stop on an initial worldwide mission to set in motion global shakubuku. In a speech he delivered in San Francisco, Ikeda invoked Christopher Columbus and likened his arrival in the New World to the inauguration in the United States of shakubuku. “We have now made the first footprint on this continent as did Christopher Columbus,” Ikeda noted. “Yet we face even a greater task than he in driving home the wedge on this tour. Twenty or fifty years from now this day will be marked with great importance.”3

At about this time, there were in the United States about 300 members of Soka Gakkai, mostly Japanese immigrants, many of them Japanese wives of American servicemen. Stories about the early efforts of these pioneering women have now taken on legendary proportions. But it does seem that much of the diversity now found in the ranks of SGI-USA can be attributed to the audacity of these women, who engaged in shakubuku in a wide range of American neighborhoods.

The first American organization, named Soka Gakkai of America and only later Nichiren Shoshu of America, was founded by Ikeda in 1960. The first English-language meeting was held in 1963, as was the first All-America General Meeting with 1,000 people in attendance. Between 1960 and 1965, tozan or pilgrimage to Taisekiji, the priesthood’s temple near Mount Fuji, was made four times by American members. By the middle of the decade, the World Tribune, the NSA newspaper, was being published. Throughout this period, NSA operated without a formal leader but grew under the informal direction of Masayasu Sadanaga, a Korean-born immigrant who was raised in Japan but migrated to the United States in 1957. In 1968, Sadanaga was appointed by Ikeda as American General Chapter Chief. Soon afterward, he changed his name to George Williams, apparently at the suggestion of Ikeda, as a way to emphasize the degree to which NSA was committed to Americanization.

As the unrest of the 1960s neared its peak, a growing number of Nichiren Buddhists, both Japanese and non-Japanese, who were committed to shakubuku and energized by the vision of kosen-rufu, could be found along with Hare Krishnas and other spiritual enthusiasts on America’s city streets. NSA’s effort to Americanize, however, encouraged a style of proselytizing that was a unique synthesis of shakubuku, American patriotism, and value creation.

The basic form of shakubuku was street solicitation—going out into the streets and inviting people to a Buddhist meeting. This created the opportunity to introduce new people to chanting, which is the basic element of Nichiren practice. In an ensuing discussion, seasoned Nichiren Buddhists would testify to how their practice brought “benefits.” These benefits could range from concrete concerns such as financial gain, good health, and good grades to more spiritual matters bearing on insight into the meaning of life. The major thrust of all these testimonials was, however, that Nichiren practice helped people to take charge of their lives and responsibility for their destinies. In Buddhist terms, they enabled practitioners to change poison into medicine, to transform negative elements in life into positive benefits.

Public ceremonies called “culture festivals” were another important part of these early shakubuku campaigns, and gave expression to the more communal element in value creation. They also were strategic devices for Americanization. For a decade and a half, NSA leaders identified Nichiren Buddhism with American values through a series of youth pageants and parades, culminating in highly publicized patriotic celebrations during the American bicentennial.

In 1976, just after NSA’s Bicentennial Convention, the organization entered into what was called Phase II. This marked a departure from the highly activist and public phase of the shakubuku campaigns. Street proselytizing was discouraged. The frenetic pace maintained by Soka Gakkai members for a decade slackened. The spirit of the organization began to shift from a collectivism driven by the energy generated by shakubuku, becoming more individualistic and inner directed. Many NSA members turned their attention to the study of the writings of Nichiren and the Lotus Sutra, personal growth, and the development of Buddhist families. A number of reasons have been put forward for these changes—a growing fear that NSA was perceived to be a cult; a response to concerns about the number of conversions dropping off; the end of the cultural upheavals of the 1960s. Whatever the case, Phase II was also in keeping with a gradual, broad moderating effect of Ikeda’s leadership since 1960.

NSA entered the 1980s claiming a membership of some 500,000, a figure most now concede was inflated. At about this time, NSA also estimated that roughly 25 percent of its members were Asian, 40 percent Caucasian, 19 percent African American, and around five percent Hispanic.4 In the late 1980s, however, long-standing tensions between the priesthood and the laity reopened, ultimately leading in 1991 to the excommunication of Soka Gakkai from Nichiren Shoshu. At that time, the lay organization adopted its current name, Soka Gakkai International. Those who renounced their ties to Soka Gakkai and allied themselves with the priests took the name Nichiren Shoshu Temple.

Sources of Schism in the Nichiren Practice and Worldview

The alliance between Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai had been mutually beneficial since its formal establishment under Josei Toda. Soka Gakkai gave to Nichiren Shoshu, a largely moribund sect in postwar Japan, a vital and international new constituency, substantial financial resources, and influence and visibility. Nichiren Shoshu gave SGI legitimacy, cultural authority, and a body of traditional religious texts, doctrines, and rituals that helped it to stand out from the pack of new religious movements that flourished in postwar Japan.

Despite the benefits each gained, there were tensions in the alliance almost from the beginning. But since the early 1990s, relatively minor events in the past have been recast by both parties in often highly dramatic terms. Given the acrimonious charges and countercharges about greedy priests and blaspheming laity, rampant egoism, and scheming power plays, it would seem to outside observers that the final break must have come as something of a relief. The often convoluted and gratuitous nature of these charges, however, should not obscure the fact that at the heart of the conflict was a fundamental dispute about the teaching of Nichiren and that for both parties a great deal was at stake. It is not without reason that the split between the two groups has been likened to the Reformation in sixteenth-century Christian Europe.

The two groups shared and continue to share many essential elements of traditional practice and a religious worldview, much like Protestants and Catholics. But as Soka Gakkai moved with increasing confidence onto the world stage, conflicts of interpretation with the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood inevitably arose over a number of issues discussed below.

Three Great Secret Laws

Nichiren Shoshu Temple and Soka Gakkai International both appeal to what Nichiren called the Three Great Secret Laws of Buddhism, as they are expressed in an age he understood to be mappo, marked by the degeneration of the dharma. These three laws are considered by both groups to be the framework of Nichiren’s Buddhism. The first law pertains to the gohonzon, a scroll that is considered the chief or supreme object of worship. The second pertains to the kaidan, or the high sanctuary of Buddhism, which Nichiren prophesied was to be built in the age of mappo. The third pertains to the daimoku, the true chant or invocation that is the most characteristic practice of Nichiren Buddhism. A consideration of each of these helps to highlight the fundamental conflict between Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai over the interpretation of basic doctrinal, ritual, and institutional issues.

DAIMOKU There is little at issue between the two groups pertaining to the daimoku, although NST and SGI have different ways of transliterating it, a point of disagreement that some observers have magnified to an extraordinary degree. In one variant, the invocation or chant consists of the words Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo, which literally mean “hail to the wonderful dharma Lotus Sutra.” Congregational chanting of the daimoku, whether in a public temple, at a community center, or before a home altar, is the most basic element in both groups. It is chanted rapidly in unison, sometimes to the accompaniment of drums, creating a dynamic and highly charged atmosphere. In most situations, the daimoku is chanted for fifteen to twenty minutes, after which the chant may change to what is called gongyo, the recitation of selected passages from the Lotus Sutra. The word gongyo means “assiduous practice,” and an assiduous practitioner might spend two hours a day chanting, with morning and evening variations in the liturgy.

The daimoku is subject to a variety of interpretations. At its most literal level, it affirms the centrality of the Lotus Sutra in the thought of Nichiren. On a more esoteric level, it is thought to be the essence of the dharma, which Nichiren Buddhists often refer to as the “mystic law,” as it is manifest in the age of mappo. Nichiren called daimoku the king of all sutras, seeing in it the explanation of the interdependence of all phenomena. Some modern interpreters have likened it to Albert Einstein’s formula for relativity, E = mc2. Others see each syllable of the daimoku as revealing rich and diverse depths of religious meaning, one reason why a small variation can become a source of great controversy.

Like the Nembutsu of Jodo Shinshu, the daimoku had a long history of use in Mahayana Buddhism before it gained prominence through its use by a particular sect of Japanese Buddhism. But the daimoku is not chanted out of gratitude and has no relationship to Amida Buddha. Nichiren Buddhists consider it a most effective practice, essential to the attainment of enlightenment.

GOHONZON Very serious matters, however, are at stake in regard to the gohonzon, the subject of Nichiren’s second Great Secret Law for the age of mappo. The gohonzon, a term often translated as the true or supreme object of worship, plays a central role in the religious life of the members of both SGI-USA and Nichiren Shoshu Temple. The typical gohonzon in the possession of a lay believer is a small paper scroll that is a consecrated replica of ones originally inscribed by Nichiren. The daimoku is printed on it in Japanese characters, surrounded by the signs of buddhas and bodhisattvas prominent in the Lotus Sutra. The gohonzon is enshrined in a home altar and treated with great care. It is thought to embody the dharma and also to embody Nichiren, who, as an incarnation of the eternal Buddha, infused his enlightenment into his original gohonzons. Facing the gohonzon while chanting daimoku, a practice referred to as shodai, is considered to be highly efficacious for the realization of one’s own true nature and for the attainment of supreme enlightenment.

The gohonzon is also a point of great contention between the priesthood and Soka Gakkai. Under pre-schism arrangements, the high priest at Taisekiji had the ritual authority to consecrate new gohonzons, thereby enabling their mystical dharma nature to come forth. Priests also had the authority to issue gohonzons to all new practitioners through gojukai ceremonies conducted at local or regional temples. Nichiren Shoshu doctrine taught, moreover, that the power of all gohonzons flowed from the dai-gohonzon, the camphor wood original carved by Nichiren himself, which is housed in the temple at Taisekiji. This meant that not only the authority but also the transformative power and symbolic heart of the religion were in the hands of the priests at Taisekiji. After the schism, the Nichiren priesthood withheld all new gohonzons from members of SGI. It has also vociferously denounced gohonzons acquired from other sources as blasphemous counterfeits. These esoteric issues may seem alien, but they are directly comparable to similar controversies about authority and ritual efficacy that deeply preoccupied Protestants and Catholics in Reformation Europe.

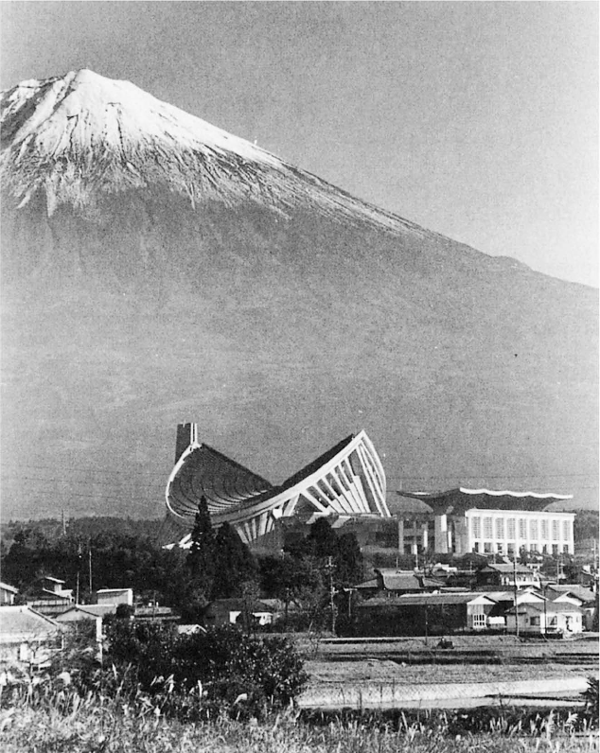

The Sho-Hondo was built with contributions from the laity to house the dai-gohonzon at the Nichiren Shoshu temple complex at Taisekiji, on the flanks of Mount Fuji in Japan. In the wake of the schism, the Nichiren Shosho high priest ordered its demolition, which was carried out in 1998 amid protests from the international architectural community.

SOKA GAKKAI INTERNATIONAL

KAIDAN Religious conflicts are also raised by doctrines concerning the third of Nichiren’s Great Secret Laws, the establishment of the kaidan or highest, most holy sanctuary of Nichiren Buddhism. In its most elementary sense, kaidan means “ordination platform,” the place where a Buddhist formally takes the precepts. But in Nichiren’s thought, the kaidan took on a greater importance because he sought for his movement an authority independent of all other Buddhist religious institutions in Japan. In the course of Nichiren’s life, the two other Great Secret Laws—the daimoku and the gohonzon—had been established, but he prophesied the kaidan would be established later, in the age of mappo.

As a result, the kaidan in the Nichiren Shoshu tradition has taken on a mystical, sometimes apocalyptic significance. Its establishment is seen as playing a central role in kosen-rufu, the dissemination of true Buddhism, peace, and harmony throughout the world. The orthodox Nichiren Shoshu interpretation of kaidan identifies it as Taisekiji, the temple founded in the thirteenth century by high priest Nikko Shonin, which has since then housed the dai-gohonzon. Tozan, pilgrimage to Taisekiji to venerate the dai-gohonzon, is seen as an important means of enhancing the efficacy of practice before the household gohonzon.

For Soka Gakkai, the orthodox understanding of kaidan took on a special twist. In 1972, a new, modern sanctuary to house the dai-gohozon, called the Sho-Hondo, constructed largely by the efforts and at the expense of Soka Gakkai, was completed at Taisekiji. Ikeda and others saw it as a sign of a pivotal role to be played by Soka Gakkai in kosen-rufu, one related to its global mission. For Nichiren Shoshu traditionalists, however, this understanding of kaidan was a bald-faced attempt on the part of Ikeda and Soka Gakkai to usurp the traditional and orthodox prerogatives of the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood. After the schism in 1991, SGI loyalists were denied the right to make tozan and were barred from entering Taisekiji. In 1998, the high priest of Nichiren Shoshu expressed his determination to demolish the Sho-Hondo, a noteworthy piece of modern Japanese architecture, in order to erase the memory of Soka Gakkai from Taisekiji. At this writing, demolition is complete, despite an international protest by architects with little invested in the doctrinal conflict between SGI and NST.

The potential for doctrinal conflict between the Taisekiji priesthood and Soka Gakkai laity is nowhere more apparent than in the Nichiren Shoshu understanding of triple refuge. In most Buddhist traditions, triple refuge refers to the Buddha, the dharma or law, and the sangha or community. Nichiren Shoshu, however, understands the Buddha to be Nichiren himself, whose teachings in the age of mappo supplanted those of Shakyamuni. The dharma or law is thought to rest in Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo—in the daimoku or chant—but especially in the gohonzon. On both these points, Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai remain in fundamental agreement.

The Nichiren Shoshu doctrine on the sangha is where the two groups naturally part company. According to Nichiren Shoshu, the sangha is exclusively identified with the priesthood, more particularly with the lineage and person of the high priest at Taisekiji. The integrity of this exclusive lineage is seen as essential to the maintenance of orthodoxy, Nichiren’s teachings, the attainment of enlightenment, and the future of kosen-rufu. Despite Ikeda’s earlier statements to the contrary, this became an untenable position for Soka Gakkai and its lay members, especially in the United States, as Nichiren Buddhism and value creation came to be increasingly shaped by the ideals of egalitarian democracy.

The schism between Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai, though involving money, power, and egotism, ultimately rests on fundamental religious issues as they relate to the mission and character of two very different kinds of institutions. To a limited degree, the analogy to the Reformation in Europe is useful. Nichiren Shoshu, like the Roman church, had a centuries-long history during which it came to understand itself as the guardian of orthodoxy. Its doctrines and practices reflected that understanding. To stretch the analogy, all Nichiren Shoshu roads led and lead to Taisekiji. In and of itself, this is no particular problem, as is evidenced by the fact that many individuals, both Japanese and western, remain loyal and fervent practitioners in the Nichiren Shoshu tradition of Taisekiji. But the Nichiren priesthood’s lock on doctrine and authority became increasingly problematic as Soka Gakkai developed into a confident and highly dynamic mass movement. Tensions that could be swept aside under Josei Toda, when the organization remained exclusively Japanese, became increasingly unmanageable as Soka Gakkai, under the leadership of Daisaku Ikeda, became a global movement.

Most observers of the schism suggest that the vast majority of American Nichiren Buddhists remained within SGI. Some Nichiren Shoshu Temple members seem to have distanced themselves from the more extreme expressions of emotions that the conflict occasioned, but the pain is such that anti-SGI invective is often found on Nichiren Shoshu websites and in its literature. Rank and file in both camps sometimes seem confused about the issues and dismayed about the break—reminders that many aspects of the controversy make sense in Japan but have little resonance in this country.

It appears that the general response by the Nichiren Shoshu Temple members has been a kind of retrenchment and inward turning. But orthodox Nichiren Shoshu has not lost its religious appeal for some American laity. One stalwart posted an account of a tozan he made in the late 1990s, which conveys the enduring appeal of Taisekiji. Here he describes his first visit to the Sho-Hondo, before it was marked for demolition:

As the High Priest entered and began to chant Daimoku, the air became filled with electricity once again. I realized at that time that the High Priest is an expert at the practice of Buddhism. We were in awe as the 65 foot high Butsudan doors opened, revealing the golden house of the Dai-Gohonzon. A priest climbed the stairs and reverently flung open the doors, exposing the Supreme Object of The Law.

The daimoku being led by the High Priest felt like a fine-tuned, high performance engine, but it was not raw power, but a gentle yet profound form of energy one could never imagine, and cannot be put into words. The compassion emanating from the Voice of the High Priest was totally unexpected by me as well as most others. It was obvious that the power of the Dai-Gohonzon is absolute. It is we who choose to deviate and cause ourselves needless suffering. That 30 minute span we spent before the Dai-Gohonzon … is frozen in time, embedded in my life.… I thank the High Priest and the priesthood from the depths of my life for preserving the Dai-Gohonzon, as well as the formalities and doctrines of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism.5

For its part, SGI emerged from the schism energized by freedom from the restraints of the priesthood to face a promising future in the United States. New and old members alike note that the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood never played a particularly important part in their religious lives. Aside from the gojukai ceremony to receive the gohonzon, which was often quite perfunctory, priests had little contact with laypeople. At the peak of its development, Nichiren Shoshu of America had only six regional temples to serve several hundred thousand members spread across the country. Members’ homes have always been the movement’s central gathering places. Its district organizations have always been organized and run by lay members, who have always occupied every office in SGI-USA, from its headquarters in Santa Monica, California to its many regional and local organizations.

New initiatives inaugurated by Daisaku Ikeda continue to lead SGI-USA in progressive directions. Beginning in the 1990s, he acted as a catalyst for a thorough rethinking of all SGI-USA organizations, urging across-the-board democratization in an effort to dismantle a hierarchical mentality inherited from the earlier era. Sacramental roles are now played by volunteers in nonpaying ministerial offices that are filled on a rotating basis. New initiatives have been put in place to enhance the ethnic and racial diversity of SGI-USA and to give women, who have always played a critical role, a higher profile at the top of the national leadership. Religious dialogue, both interreligious and inter-Buddhist, is now on the SGI agenda, which would not have been the case under the sectarian leadership of the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood. All of these initiatives have contributed to an opening up of Soka Gakkai. A frequent statement in leadership circles is that a new, egalitarian SGI is “a work in progress.”

New institutions have also been established that, while infused with the religious spirit of Nichiren Buddhism, are devoted to the kind of progressive and humanistic value creation first outlined by Tsunesaburo Makiguchi. Nonsectarian Soka University of America in southern California was founded by Ikeda in 1987 with a mission to educate an international student body for leadership positions around the Pacific rim. The Boston Research Center for the Twenty-first Century, located in Cambridge, Massachusetts next to Harvard University, is devoted to fostering humanistic values across cultural and religious lines. Since it was founded by Ikeda in 1993, it has sponsored a wide range of conferences, symposia, and research initiatives on such topics as the world’s religions and the ethics of ecology, global citizenship and human rights, and development of leadership initiatives among women.

The innovations in SGI since the schism have had different impacts in different countries, but in the United States have helped to transform SGI-USA into a form of lay Buddhism quite in keeping with the tenor and values of a moderate moral and religious current in the American mainstream. Discussion with SGI-USA members reveals that to a striking degree, many American values are also Nichiren Buddhist values. Some members emphasize how Nichiren practice helped them gain control of their lives and brought great material benefits. Others stress increased emotional and physical well-being. But they also repeatedly refer to the importance of Buddhist practice in building character and fostering personal responsibility.

Linda Johnson, a long-time practitioner who is a supervisor in the Criminal Division of the California Attorney General’s Office, is among the many SGI members who are articulate about how Nichiren Buddhism has changed their life and given it meaning. Raised a Methodist in the 1950s in an extended family that included Caucasians, Native Americans, and African Americans, Johnson was first drawn to Soka Gakkai in the 1970s, while in law school at the University of Southern California. She was impressed by SGI’s ethnic diversity but even more so by the genuine bonds among the people within it. She recalls that the gohonzon and chanting daimoku first struck her as strange, but “I trusted my gut and felt there was something real about these people. They were not faking their happiness. They had something in their life that I knew I wanted and did not have.”6

One turning point in her practice came during her bar examination several years later, when chanting helped her to focus her mind, control her fears, and tap into her deepest potential, which she refers to as her “Buddha nature.” Another, more important turning point came around 1980, when she first met Daisaku Ikeda. As with many others in SGI, his example led her deeper into practice and the study of Nichiren’s teachings. “Here was this short Japanese man with a life force that made it seem like he was ten feet tall. He had the most positive energy and was, at the same time, the warmest and most magnanimous human being I had ever experienced. The practice had to be right because of the qualities this man had.”

Johnson considers Nichiren Buddhism to be a “difficult practice.” She tries to chant daimoku two hours a day, in addition to morning and evening gongyo, saying that it enables her “to meet life head on, moment to moment, to constantly work at overcoming fear, doubt, and negativity, and to plug into the enlightened nature.” In her work in the State Attorney General’s Office, she often prosecutes death penalty cases before the California Supreme Court. Given the gravity of her work, she finds that chanting helps her maintain clarity of mind and purpose. She understands her role is to enforce the laws of the state of California. But she also knows that the law of cause and effect as taught by the Buddha is also at work in all these cases, unfolding in complex ways among the accused and the victim, families and friends, in ways she is unable to determine. “The mystic law is infinitely more profound than my brain is,” Johnson notes, “so I try to suspend my own mental judgment, not figure out how I think the effect should come about, and trust that the higher law will determine the right thing for each person.”

During her more than twenty years of practice, Johnson has served in a succession of leadership positions from Junior Hancho (han means “group” and cho, “leader”), to Hancho and District Leader. She is currently Vice Women’s Leader in the L.A. #1 Region and in the Women’s Secretariat, where she assists the national head of the women’s division. She also heads the Legal Division in the SGI-USA Culture Department, which means that she acts as a kind of spiritual adviser to other lawyers who practice Nichiren Buddhism. Before the schism in 1991, Johnson traveled to Japan at least eight times to meet with other leaders and to see the dai-gohonzon at Taisekiji, which she considered a powerful experience. “But for me the cause at work in chanting before the dai-gohonzon was pure heart and sincerity of prayer, not the high priest,” she recalls. She also thinks that the break, however difficult it may have been for some people, “was a great thing. It enabled us, sometimes forced us, to face issues, to see Nichiren’s Buddhism for ourselves. It has enabled the organization to make the equality of all people, our common Buddha nature, more real and concrete.”

Ikeda’s writings convey the same ardor for character found among members of SGI like Johnson, together with a strong commitment to Nichiren Buddhism. He has written widely and in depth on Mahayana Buddhism, Nichiren, and the Lotus Sutra, and has undoubtedly recast many of the doctrines central to the orthodoxy of Nichiren Shoshu. But in his writings and speeches designed for the broader world, Ikeda has called, in very plain language, for nothing less than a new Buddhist humanism that can revolutionize the twenty-first century through the inner transformation of the individual and the reordering of an increasingly interdependent global society. This call is a modern restatement of Nichiren’s visions of kosen-rufu, which he first articulated in the thirteenth century. But it also reflects Ikeda’s vision of world peace, Josei Toda’s commitment to shakubuku, and Tsunesaburo Makiguchi’s passion for progressive education.

As the dust settles from the break between NST and SGI-USA, the latter appears to be in a very good position to play an important, ongoing role in the creation of American Buddhism. The Nichiren tradition provides a rich foundation for philosophical reflection and practice. The tenor and tone of the movement are very much in keeping with mainstream American values, while its varied membership gives it a multicultural and multiracial dimension that ought to be an asset in the next century. As a result of adjustments the organization has made since 1991, SGI has a very unambiguous lay orientation, unlike American Zen, for instance, which has lingering unresolved issues related to the monastic character of its practice traditions. At the same time, SGI-USA maintains strong links to its origins in Japan which, as in the case of Zen, can be a source of some tension in the organization. But the connection can also be considered an asset. SGI-USA is in many respects a thoroughly Americanized form of Buddhism, and this could easily lead to a dissipation of its unique energy; the need to be alert to developments in Japan may well serve to maintain the movement as a distinct feature of the American religious landscape.