At least three interrelated forces have been at work in the transmission and adaptation of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition to America over the course of the last several decades. All were set in motion by the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1950 and by the creation of a Tibetan community in exile in 1959, after the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s political and spiritual leader, escaped to India, eventually followed by about a million Tibetans. Given Tibet’s unique circumstances, the cross-cultural transmission of its religious traditions has been particularly dramatic, as elements of an entire civilization that was suddenly shattered were selectively transplanted into the vastly different society and culture of the United States.

One of these forces, the campaign for a free Tibet, became a celebrated cause in America’s human rights and entertainment communities, a development that brought all things Tibetan to the attention of the American mainstream. What Alan Watts, D. T. Suzuki, and the Beat poets did for Zen in the 1950s, political activists and Hollywood filmmakers and stars did for Tibetan Buddhism in the 1990s. A second, less noticed, but highly significant development was a concerted effort on the part of Asian and western Buddhist scholars and publishers to preserve Tibetan religious texts and disseminate them in the West. This cause was taken up with urgency due to China’s determination to eradicate Tibet’s religious traditions and institutions. A third force, crosscut by political and preservation concerns, was the establishment of an extensive network of practice centers by lamas and their students, beginning in the 1960s.

Additional factors have helped to create a uniquely Tibetan milieu in this country. Tibetan Buddhism arrived largely untouched by the kind of wholesale modernization processes that transformed Buddhism in Japan. As a result, its religious worldview remains, for lack of better terms, traditional or pre-modern. Complex mythologies and ritualism are at the center of Tibetan Buddhism, as is an unapologetic, devotional regard for lamas, many of whom are considered reincarnations of highly realized beings. Another factor is the demographics of Tibetan Buddhism in this country. There are only about ten thousand Tibetan exiles and immigrants in America. As a result, Tibetan Buddhism here is largely a community of discourse that includes lamas living both in this country and in Asia, committed scholars and political leaders, a small clutch of exiles, and practicing converts, who form the largest part of the community. No figures are available on how many Americans are Buddhists in the Tibetan tradition, but since the 1970s they have been a prominent and very distinctive feature of American Buddhism.

There are differences among Tibetan Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism, and Vajrayana, but the terms are used more or less synonymously in this country. They are part of a broad stream of Buddhism that originated in India but traveled with the Mahayana tradition through China to Japan, taking on a unique form in the Tibetan region of central Asia, where it fused centuries ago with local shamanic traditions. Tibetan Buddhism is structured by a complex and sophisticated set of organizations in this country. Its major schools all have budding flagship organizations and are represented by many highly regarded teachers, a few of whom we will come to presently. The trauma resulting from the Chinese invasion of Tibet and the resulting emphasis on the preservation of its traditions in exile have given much of the religious activity in the community a conservative slant. At the same time, however, a number of its leaders and teachers, both Asian and American, are regarded as brilliant innovators.

Politics and Celebrity on the Road to Americanization

Serious interest in the practice of Tibetan Buddhism has been on the rise in the United States since the 1970s, but Tibet momentarily seized the spotlight in America in the 1990s. Much of the fascination with Tibet at that time was infused with romantic idealism, which often obscured the complexity of Tibetan society and its religious traditions. But through a powerful alliance between Tibet support groups and Hollywood, Americans’ awareness of Tibet was greatly heightened, a phenomenon that was also a peculiarly American moment in the history of the cross-cultural translation of the dharma.

At the heart of it all was Tenzin Gyatso, the fourteenth Dalai Lama. His high public profile is based in part on his dedication, charm, and commitment to principles of nonviolence, which have elevated him to Gandhi-like status in the eyes of many Americans. It is also based on the fact that he has been a tireless worker for the Tibetan people since his exile and an assiduous traveler since his first trip to the West in 1973. Both his personal commitment and his work on behalf of his people won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989.

The Dalai Lama is seen as a spiritual leader with authority and expertise that appeal to a varied constituency. During a two-week stay in Los Angeles in 1989, for instance, he spoke before a Chinese American audience at Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights, the largest Buddhist monastic complex in the West, where he addressed the assembled as his Chinese brothers and sisters. He spoke to a gathering of American convert and immigrant Buddhists from communities in southern California and gave a public, general-interest lecture to 5,000 in the Shrine Auditorium on the topic of inner peace. In a more practice-oriented vein, he also performed a mass Kalachakra initiation, one of a large number of Tibetan Buddhist empowerment ceremonies, for 3,000 Buddhists and any others who cared to attend. He then addressed medical doctors, scientists, and philosophers, who had requested him to speak on the nature of human consciousness and mind/body relations.

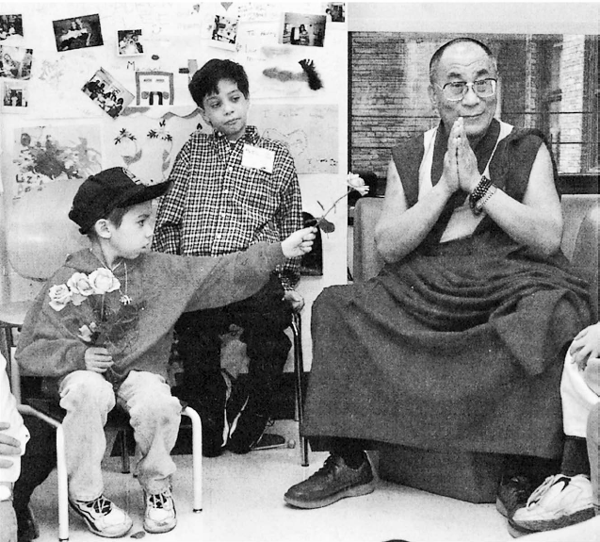

Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, is a Gelugpa monk and the political and spiritual leader of the Tibetan people. His dedication to the cause of Tibet, his religious integrity, and his personal warmth made him among the most popular and charismatic Buddhist leaders in the West in the 1990s. AP PHOTO

Because the Dalai Lama is also the political leader of his country and an astute statesman, his tours usually balance politics with religion. During a 1997 tour to Washington, D.C., he was particularly concerned with courting the American political establishment, where sympathies for Tibet were warming. He met with President Clinton and Vice President Al Gore at the White House and was hosted by members of Congress, including the chairs of both the House and Senate committees on foreign relations. He was introduced to Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, Speaker Newt Gingrich, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, and other congressional leaders. But he also met with American Jewish and Christian leaders, joined an Interfaith Prayer Gathering for Religious Freedom at the Washington National Cathedral, and attended the inaugural Passover ritual held by a movement called Seders for Tibet.

The Dalai Lama’s political work in the 1990s received critical support from a wide range of Tibet support groups working both in the upper echelons of American society and at the grassroots. The U.S. Tibet Committee in New York, an independent human rights organization of Tibetan and American volunteers, promoted public awareness of Tibet through lectures, demonstrations, and letter-writing campaigns. The International Campaign for Tibet, located in Washington, D.C., worked primarily with elected officials, but also provided assistance to grassroots groups such as Los Angeles Friends of Tibet (LAFT). LAFT is primarily devoted to public education in Los Angeles, but has been a consultant to the Hollywood studios and coordinated publicity for the Dalai Lama’s southern California tours. It is one of many independent, community-based organizations loosely affiliated as Friends of Tibet.

Other support groups used a range of strategies to educate the public about Tibetan issues. Students for a Free Tibet, the leading group on campuses, tapped into the student activism once devoted to the movement to end apartheid in South Africa. It began in 1994 with 45 chapters nationwide, and by 1997 had 350. Students played a key role in helping the London-based Free Tibet Campaign persuade Holiday Inn to pull out of Lhasa, Tibet’s capital city. Rangzen, the International Tibet Independence Movement, is headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. One of its major activities was to sponsor marches for Tibet’s independence. Its 1997 march was a 600-mile, three-month-long trek from Toronto to New York City. In 1998, another went from Portland, Oregon to British Columbia, concluding at the consulate of the People’s Republic of China in Vancouver. Both marches were led by Thubten J. Norbu, the elder brother of the Dalai Lama and President of the Tibetan Cultural Center in Bloomington, Indiana.

Other organizations dedicated to Tibet operated across the spectrum of American culture. At the pop end, the Milarepa Fund, founded by Adam Yauch of the rap/hip-hop group Beastie Boys, was best known for its sponsorship of Concerts for a Free Tibet, a series of performances by cutting-edge rock groups designed to introduce Tibetan issues to pop music fans. “For the most part the fans have been really cool and fascinated by the monks, blown away,” Yauch noted. “They just emanate so much love and compassion that everyone on the tour and the other bands are drawn to them.”1 A self-identified Buddhist, Yauch was largely responsible for introducing the dharma to a generation more or less untouched by the 1960s-era enthusiasm for Buddhism. At the more establishment end of the spectrum was Tibet House in New York. Founded in 1987 at the request of the Dalai Lama, this cultural center and art gallery educates the public with exhibits, lectures, and workshops about Tibet’s living culture and distinctive spirit. Its co-founder and current president is Robert Thurman, the Jey Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University, a former Tibetan monk, author, and outspoken American Buddhist leader.

Hollywood added both the luster of celebrity and a powerful dose of publicity to the campaign for Tibet, which reached a critical mass in 1997, the annus mirabilis for Tibetan issues. Between October and December of that year, Hollywood propelled Tibet into the public eye with the release of Red Corner, a movie trashing the Chinese justice system, starring Richard Gere, one of America’s long-time, high-profile Buddhists; Seven Years in Tibet, starring box-office idol Brad Pitt; and Kundun, a story about the childhood of the Dalai Lama directed by the eminent filmmaker Martin Scorsese. Each premiere served as the occasion for interviews, protests, nationwide campaigns, and Tibet-related appearances by celebrities.

The release of Seven Years in Tibet also prompted Time magazine to run a cover story, “America’s Fascination with Buddhism,” that despite its glibness (“All over the country, pop goes the dharma”) and star-struck tone (“Bodhisattva Brad?”) signaled a resurgent Buddhist vogue reminiscent of the ’50s Zen boom. In the same year, moreover, Penor Rinpoche, head of the Nyingma school, announced that he had recognized Steven Seagal, the action-adventure film hero, to be a tulku, the reincarnation of a seventeenth-century monk and lama whose teachings had been destroyed by the Chinese. This elicited so much cynical commentary about celebrity Buddhists in general and Seagal in particular (one journalist dubbed him “the homicidal tulku”2) that Penor Rinpoche soon issued a press release to clarify issues. “Some people think that because Steven Seagal is always acting in violent movies, how can he be a true Buddhist,” he wrote from Namdroling Monastery in India.

Such movies are for temporary entertainment and do not relate to what is real and important. It is the view of the Great Vehicle of Buddhism that compassionate beings take rebirth in all walks of life to help others. Any life condition can be used to serve beings and thus, from this point of view, it is possible to be both a popular movie star and a tulku. There is no inherent contradiction in this possibility.3

All the publicity evoked cautious responses from much of the convert Buddhist establishment, where many people who had been practicing the dharma for thirty years seemed put off by all the attention. Tricycle, a respected Buddhist review, asked in a cover story: “Hollywood: Can It Save Tibet?” In a piece on the image of Tibet in films from Frank Capra’s 1937 classic Lost Horizon to the present, one author concluded Hollywood was “relevant—maybe even critical” to the outcome of Tibet’s political struggle.4 Similarly cautious applause came from Stephen Batchelor, an influential British Buddhist who was in New York for a forum with Philip Glass, the avant-garde composer and long-time Buddhist who wrote the score for Kundun. “Perhaps it doesn’t matter how Buddhism—the dharma—filters into the culture,” Batchelor told the New York Times. “What matters is whether people take it up and change their lives.”5

Tibet support groups made use of all the coverage but considered it both temporary and superficial, and they anticipated that corporate America, with eyes to China’s vast markets, would soon put a lid on the media’s pro-Tibet sympathies. But as Larry Gerstein, co-founder of Rangzen with Thubten J. Norbu, noted in the midst of it all, the media attention had some positive effects: “We’ll have to see whether all this publicity translates into broad-based, public support. But at least people now know why we are marching. A few years ago a lot of folks asked, ‘What’s Ty-bet?’” 6

Preservation and Dissemination of Texts

A second, very different avenue for the transmission of Tibetan Buddhism to the United States has been the effort of many people to preserve Tibetan religious texts and disseminate them in this country. When refugees fled Tibet for India, they left behind great works of art, ritual paraphernalia, and a vast number of Mahayana and Vajrayana texts, all of great importance to the study and practice of Buddhism, and a great many unknown in the West. Over the next twenty years, an estimated 6,000 monasteries, plus temples and other landmarks, were demolished. Art was destroyed and monastic libraries were burned. Monks and nuns were tortured and imprisoned, and hundreds of thousands of Tibetans were killed in the course of a campaign aimed at the extinction of a civilization. China’s policies gave the work of preservation and transmission of the Tibetan tradition a particular urgency. If Tibet were destroyed, its traditions would live on only in religious texts and in a generation, perhaps two, of exiled Tibetans.

The arduous task of collecting, preserving, translating, and disseminating Tibetan texts was first taken up in this country in the 1960s by lamas in exile and their students. More than teachers from other traditions, these lamas encouraged their students to take advanced degrees in Buddhist Studies and to seek jobs in the academy. Among the most influential of these students-turned-academicians is Jeffrey Hopkins, whose writing, research, and teaching in the Buddhist Studies program he founded at the University of Virginia have been critical in advancing the study of Tibetan Buddhism in this country. The rise of Tibetan studies helped to change the evaluation of Tibetan Buddhism in the West, where it had been dismissed by many scholars as a corrupt form of the dharma. In the 1970s, a range of Buddhist presses became selectively engaged in the distribution end of the preservation and translation work. Whereas in 1960, only a few older translations of classic texts such as The Tibetan Book of the Dead were readily available in American bookstores, by the mid-’90s a wide range of philosophical and liturgical texts were on the open market, many of which had been considered secret teachings for centuries.

A number of publishing concerns, all with strong links to the American Vajrayana practice communities, played a central role in this activity. Wisdom Publications is a nonprofit organization associated with the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), an international network of practice centers founded in the 1970s by Lamas Thubten Yeshe and Thubten Zopa Rinpoche. Wisdom is dedicated to the publishing of the work of the FPMT founders as well as translations of sutras, tantras, other Tibetan texts, and a range of general Buddhist literature.

The premiere English-language publisher of scholarly and trade books about Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism is Snow Lion Publications, located in Ithaca, New York. Formed in 1980, Snow Lion is closely associated with the Gelugpa tradition and its spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, whose North American monastic headquarters, Namgyal Monastery, is also located in Ithaca. Since 1984, Snow Lion has published fourteen books by or about the Dalai Lama. But its extensive Tibetan material also includes translations of philosophical, ritual, and devotional texts, and books devoted to Tibetan history, art, and culture. Snow Lion has been instrumental in distributing the work of a pioneering generation of scholars of Tibetan Buddhism, but it maintains a popular profile as well by distributing Vajrayana-related audiovisual material, T-shirts, posters, and ritual and decorative paraphernalia.

Shambhala Publications is the foremost general-interest publisher in the American Buddhist community. Founded in 1969, it has been a part of the Buddhist phenomenon among the baby-boom generation almost from the start and, together with Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, it is a significant public voice of the convert community. Among its most successful titles are The Tassajara Bread Book, now a Zen standard from the counterculture era, and Fritjof Capra’s Tao of Physics, a pioneering popular book about the interface between science and Asian religion. Shambhala is also well known as the publisher of the works of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a teacher who played a key role in the Tibetan part of the convert community throughout the 1970s and into the ’80s. Its first publication was Trungpa’s Meditation in Action, released while he was still in England. In 1973, it published his Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, a path-breaking book at the time and now an American Buddhist classic. Shambhala continues to maintain a full line of Trungpa’s work in print, but it also has a history of publishing a broad range of Asian and western spiritual texts in a variety of paperback and pocket-sized editions. Since 1974, its distribution agreement with Random House has enabled it to make an unusually significant contribution to the introduction of Buddhism into mainstream America.

In contrast, Dharma Publishing, founded by Lama Tarthang Tulku in Berkeley, California in 1971, is run by the lama’s nonsalaried, long-time students and takes a quasi-monastic approach to texts. Dharma Publishing has many projects, but one ongoing effort has been the creation and distribution of a limited edition, 128-volume collection of the Kangyur and Tengyur, the canonical scripture of Tibetan Buddhism. Each atlas-sized volume weighs ten pounds, is hand bound, and is printed on acid-free paper to ensure its survival for centuries. Each contains about 400 gilded pages of photocopied block print texts, a Tibetan sacred painting called a thangka, line drawings of a founder of one of the Tibetan schools or lineages, historical maps, and an image of one of Tibet’s many buddhas, all selected to honor the wisdom contained within the text and to delight readers. This attention to detail reflects the devotional regard in which the Kangyur and Tengyur are held by Tibetans, who display the volumes above the central altars in shrine rooms and prostrate themselves before them as a devotional exercise. Dharma Publishing is now located at Odiyan, an extraordinary monastic complex in northern California designed by Tarthang Tulku, which serves as a study and retreat center for his practice community.

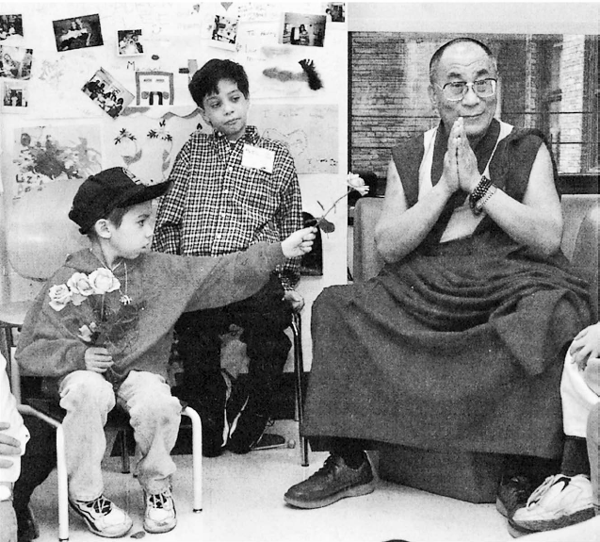

Chogyam Trungpa, whose book Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism is an American Buddhist classic, was one of the most innovative of the many Tibetan lamas to come to the United States during the Buddhist boom of the 1960s. He is shown here teaching at Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, one of the institutions that are part of his legacy in this country. SHAMBHALA SUN

A monastic spirit also infuses the Asian Classics Input Project (ACIP) directed by Geshe Michael Roach, a Gelugpa monk and the first American to receive the geshe degree, the Tibetan equivalent of a doctorate in philosophy. But ACIP is working to produce a scholarly edition of the Kangyur and Tengyur, together with philosophical commentaries and dictionaries related to them, in a searchable format on CD-ROMs, which are made available at a nominal cost to scholars, research institutions, and practice communities. For more than twenty years, Roach studied with Geshe Lobsang Tharchin, the abbot of Sera Mey monastery, once located in Lhasa but rebuilt in south India after the Chinese occupation of Tibet. Young monks in exile now perform data entry for ACIP at Sera Mey, a task that helps to support the impoverished monastic community. The marriage of ancient wisdom and high technology epitomized in the work of ACIP is captured in the poem “In Praise of the ACIP CD-ROM: Woodblock to Laser,” by Gelek Rinpoche, another tulku who is a highly regarded teacher and the founder of Jewel Heart, a network of Buddhist centers in half a dozen cities here and abroad.

A hundred thousand

Mirrors of the disk

Hold the great classics

Of authors

Beyond counting.

No longer

Do we need

To wander aimlessly

In the pages of catalogs

Beyond counting.

.......................................

With a single push

Of our finger

On a button

We pull up shining gems

Of citations,

Of text and commentary,

This is something

Fantastic,

The Vajrayana Practice Network

The campaign to free Tibet and the preservation and dissemination of texts have been central to the transmission of Tibetan Buddhism to America, but the living heart of the process is found in a practice network built by lamas and their American students. By and large, Tibetan centers in this country are not highly politicized, although the issues surrounding Tibet in exile necessarily pervade the community. But the unique circumstances created by the need to preserve Tibet’s religious life have given a traditional cast to much of their activity. Prayer flags, prayer wheels, thangkas, butter lamps, and the cultivation of Vajrayana meditative practices in gemlike shrine rooms help to re-create a uniquely Tibetan ethos in the West that is devotional, highly festive, and contemplative.

The first lamas in exile began to arrive in America in the late 1950s, but Tibetan Buddhism became popular only in the late ’60s and ’70s. At that time, pioneering teachers such as Kalu Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche began to draw large numbers of students both in America and in Europe. For many westerners, the discovery of these lamas was a transforming experience, much like that of Americans who first encountered Japanese Zen teachers. For many in an older generation of American practitioners, these lamas retain a legendary aura and status, as is suggested in this poem by a student of Kalu Rinpoche written in 1997:

Kalu in ’72

sat still,

spoke Tibetan quietly,

and I of course didn’t

understand a word.

exotic melodious sounds

filled my body.

translation wove itself in

voices and color …

dark red robes, small thin body,

occasional slight smile on the calm

weathered face.

the unforgettable face …

I didn’t know then how many times

Kalu would appear in dreams of

golds and deep reds,

that decades later in another city

I would echo the ancient bodhisattva vows,

Kalu again before the room,

even more gaunt now,

old thin yogi wrapped in folds of red.8

Throughout the 1970s, the foundations of the Vajrayana practice network were laid as students gathered around teachers, rented temporary dharma halls, and began to purchase property, a process much like that in American Zen, only a few years later. Like American Zen, Tibetan Buddhism in this country has no central administration. Its practice centers are organized as schools and along the spiritual lines of specific teaching and practice lineages. There are four main schools in Tibetan Buddhism, the Gelugpa, Kagyu, Nyingma, and Sakya, but within these are many different lamas who run centers more or less in accord with the traditions of their teacher and his or her lineage. While one can speak of an American Vajrayana community as a whole, it is really more a patchwork of small sub-communities often quite separate from each other, but all maintaining living links through their teachers to the broader Tibetan community in exile.

A brief look at the Kagyu, a school with well-developed American institutions, suggests the organization of this network in all its fascinating complexity. The Kagyu school is a cluster of teaching and practice lineages associated with the tenth-century Indian king Tilopa, the Tibetan master Marpa, and his great student, the ascetic Milarepa. Kalu Rinpoche was among the earliest and most important Kagyu lamas to teach in America, during a number of tours he made between 1971 and his death in 1989. He first gathered students around him for teachings on a temporary basis in a number of American cities.

Shortly after, resident lamas arrived to lead these ad hoc groups and to continue teaching. In San Francisco, for example, Lodru Rinpoche, a lama who had studied under Kalu and a number of other Kagyu teachers, was appointed by the head of the school to develop a group that now goes by the name of Kagyu Droden Kunchab (KDK). It occupies an apartment building in San Francisco where local members practice daily, but Lama Lodru also maintains satellite centers in Marin Country, Arcata, Sacramento, and Palo Alto, in part by means of teleconferencing. These five groups constitute the KDK teaching and practice community, a small portion of the Kagyu network, which itself is but one component of the larger American Vajrayana community.

Other Kagyu communities have a more complex structure, such as Karma Triyana Dharmachakra (KTD) in Woodstock, New York. It was founded in 1979 by the sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa, traditional head of the Karma Kagyus, a prominent lineage within the Kagyu school. At the highest level of organization, KTD is the North American seat of the Gyalwa Karmapa, an office occupied by a succession of reincarnated lamas. It is therefore closely affiliated with Rumtek monastery in Sikkim, the home of the Gyalwa Karmapa in exile, and with Tsurphu monastery in Tibet, the ancient monastic center of the Kagyus. At the same time, however, KTD operates as an American monastery, and its grounds include solitary retreat cabins, staff quarters in a rambling wood-frame farmhouse, and a monastery building constructed in the 1980s, which contains a residence for the Gyalwa Karmapa and two community shrine rooms. Under the direction of its khenpo or abbot, Karthar Rinpoche, and Bardor Tulku Rinpoche, KTD maintains a daily practice schedule for staff and guests and regularly offers both introductory and advanced classes.

But the lamas of KTD also lead more than two dozen meditation centers in about nineteen different states (as well as a number overseas), where small groups of American students practice Kagyu teachings, sometimes with a resident Tibetan instructor but more often independently. For them, KTD is a kind of continuing-education home base, which they may visit from time to time to take instruction during a weekend or week-long retreat. KTD also maintains a rural center for the three-year, three-month-long instructional and practice retreat that is a fundamental rite of passage for the advanced student. Its network also includes a stupa, a Buddhist reliquary mound and pilgrimage site, at Karma Thegsum Tashi Gomang in Crestone, Colorado, where the community plans to build an institute for the study and practice of traditional Tibetan medicine and monastic retreat facilities.

Shambhala International, another institution primarily associated with the Kagyu school, is organized similarly to KTD, but has a more complicated relationship to the Tibetan lineages. The headquarters of its far-flung network of North American and European practice centers is in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Its major retreat facility is at Rocky Mountain Shambhala Center in Colorado, where the community is creating one of the wonders of the American Buddhist world, the Great Stupa of Dharmakaya. Thanks to its founder, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Shambhala is a unique blend of Vajrayana traditionalism and American innovation. Trungpa was a tulku of the Trungpa lineage of teachers within the Kagyu school, but he was also trained in the Nyingma tradition and was an adherent of the rimed (pronounced re-may) movement, a modern ecumenical or nonsectarian form of Tibetan Buddhism. As a result, Shambhala is considered to be in both the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages and draws upon a wide range of Tibetan traditions.

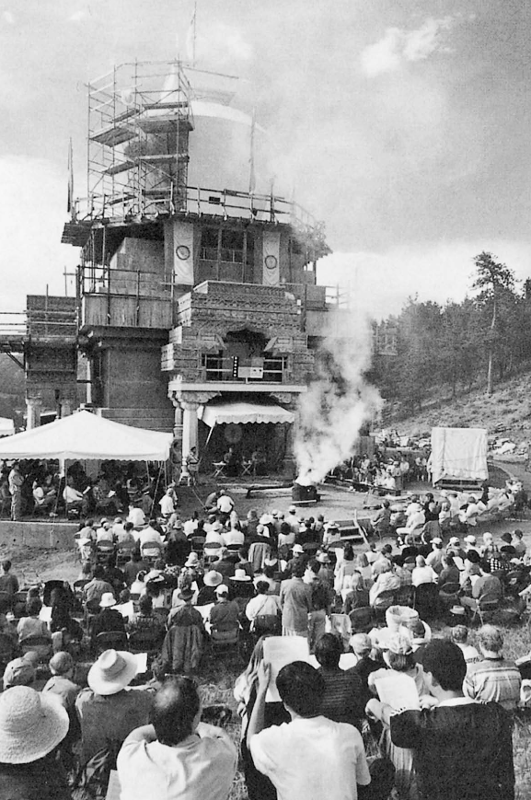

The Great Stupa of Dharmakaya at Rocky Mountain Shambhala Center represents both the high regard for tradition and the willingness to innovate found in much of Tibetan Buddhism in America. Its design is in accord with Tibetan precedents and its construction was marked by elaborate rituals, but the Americans who have dedicated years to building it have also adapted selected elements, such as cutting-edge concrete technology and a ground-floor public space, for contemporary uses.

GREAT STUPA OF DHARMAKAYA

Shambhala’s uniqueness also owes much to Trungpa’s brilliance as an innovator and interpreter of Tibetan Buddhism. Trungpa arrived in America in 1970 after studying at Oxford in England, where he relinquished his monastic vows and married. Throughout the ’70s, he was deeply involved with the countercultural movement, first in Vermont and then in Colorado, and his capacity to combine the cultivation of enlightenment with the outrageousness favored in that decade became legendary. During this period of intense activity, Trungpa laid the foundation for a range of educational, arts, and practice institutions that would eventually evolve into Shambhala International. In the 1980s, however, he shifted his base of operations to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and many of his students followed him there. His death in Halifax in 1987 led to a period of strife and confusion for his students. But the many developments in Trungpa’s community during these decades—the founding of the Jack Kerouac Chair of Disembodied Poetics in 1974; Trungpa’s cremation at Karme Choling, the Vermont center where he started his movement, in 1987; and the death of his regent Osel Tendzin (a convert named Thomas Rich) from AIDS in 1990—were among the most dramatic moments in the cross-cultural transmission of the Tibetan dharma to the United States.

In 1995, Shambhala came under the leadership of Trungpa’s eldest son, who was enthroned as the movement’s leader and is now generally referred to as the Sakyong, or earth protector. Shambhala has since then clarified its institutional structure and mission by developing three distinct gates or paths to practice, which reflect different aspects of Trungpa’s lifelong passion for the cultivation of awakened living. Nalanda is a path for the cultivation of wisdom through the integration of art and culture, which can be pursued through a range of disciplines from photography and dance to archery, poetry, and the medical arts. Nalanda is most closely associated with Shambhala’s educational activities, such as its Sea School and elementary schools in Nova Scotia and Naropa Institute, a fully accredited liberal arts college in Boulder, Colorado. A second path, Vajradhatu, is the most traditionally Tibetan, but it also reflects Trungpa’s interests in Zen and Theravada Buddhism and his concern with adapting Vajrayana to the needs of western students. This path is cultivated in a network of local practice centers called Shambhala Meditation Centers. A third, more thoroughly innovative path is Shambhala Training, which will be discussed below.

Shambhala International is among America’s most complex and innovative Buddhist institutions, but it remains intimately linked to the broader Tibetan ethos and community. The Sakyong is referred to as Mipham Rinpoche because he was recognized by Penor Rinpoche, head of the Nyingma school, to be an incarnation of Mipham Jamyang Namgyal, a revered meditation master and scholar. Thrangu Rinpoche, the abbot of Shambhala’s Gampo Abbey in Nova Scotia since 1986, is a highly trained Kagyu tulku and teacher who also heads a convent in Nepal as well as Buddhist study centers in Benares, India, and at Rumtek monastery in Sikkim. He is currently rebuilding the monastery of the Thrangu lineage in Tibet and leads a network of his own centers in America, Asia, and Europe. At the same time, however, Pema Chodron, an American student of Trungpa, a mother and grandmother, and director and resident teacher at Gampo Abbey, is both a fully ordained Kagyu nun and a highly respected and popular teacher in the broader American convert community.

These three institutions give only a small picture of the larger Kagyu network in this country, one that is more or less replicated among the Nyingma, Gelugpa, and Sakya schools. All together they form the institutional foundations for American Tibetan Buddhism and the means by which teachings and practices are being transplanted to this country, by Tibetan lamas in exile, American students, and a rising generation of American-born lamas.

Tibetan Buddhist Practice and Worldview

On a popular level, Americans are engaged with the religious traditions of Tibet in a wide variety of ways. Some are casual visitors to culture and practice centers, where they partake of the spiritual aura of Tibetan Buddhism. Others take refuge and identify themselves with the community, but limit their activities to basic meditative practices. Many hold Tibetan lamas in the highest regard and find being in their presence both inspiring and edifying, a lay devotional attitude with a long history in Tibet. The disciplined core of the community in this country, however, is made up of those students and teachers who make a serious and sustained commitment to meditation, which requires a great deal of diligence, energy, and years of practice. The variety and complexity of these practices are such that it is best to say too little about them rather than too much. But the basic practice vocabulary, understood by all the members of the community, gives a sense of the unique quality of American Vajrayana.

Shamatha and Tonglen Meditation

Shamatha, or shamatha-vipashyana, meditation is a basic element in Tibetan practice. It resembles zazen in form, with similar postures and attention to the breath, but its specific goal is the cultivation of tranquility of mind. Shamatha meditation is usually set within a ritual framework that opens with taking refuge and reciting the bodhisattva vow and concludes with a dedication of the merit accrued from the practice to all sentient beings. The cultivation of openness, healthy-mindedness, and calm make shamatha an essential introduction to higher practices, whether visualizations or higher kinds of meditation such as Dzogchen and Mahamudra, which are often compared to Zen. However, shamatha meditation can also be the central, lifelong practice of Americans who consider themselves Buddhists in the Tibetan tradition.

Tonglen, or sending and receiving practice, is a particular method of meditation in which the altruism intrinsic to shamatha is made more explicit. In tonglen, the practitioner takes in the confusion, paranoia, and suffering of the world with each inhalation and neutralizes them in mind and spirit. With each exhalation, he or she concentrates on sending goodness, health, wholesomeness, and sanity into the world. Tonglen meditation is taught by many Tibetan lamas, but it has also been made familiar to Americans by Pema Chodron in her book Start Where You Are: A Guide to Compassionate Living and other writings.

Empowerments

Abhisheka is a Sanskrit term translated as “initiation” or, more frequently, “empowerment.” It refers to a ritual process in which a lama introduces students to a particular teaching and empowers them to practice it. In traditional Tibet, such empowerments were essential to studying or practicing secret tantric teachings and they remain so in serious practice circles today.

The secrecy and strict procedures that once surrounded empowerments were relaxed in the nineteenth century, when lamas began to encourage laity to cultivate selected monastic practices. The current boom in publishing esoteric Tibetan texts has further contributed to this openness, which seems to trouble some lamas a great deal but others not at all. As a result of these changed circumstances, however, the importance placed on empowerments seems to be in flux. The Asian Classics Input Project has agreed to release some texts on computer disk only to those who have been appropriately empowered to study them. But the Kalachakra empowerment, which was formerly meant for experienced practitioners and in Tibet was held only infrequently, has become a large-scale, public event promoted by the Dalai Lama as a meritorious experience for everyone in attendance. Some Americans receive a number of empowerments from lamas but have little expectation of diligently practicing the teaching. This collection of empowerments often draws criticism from serious students, but others consider it a form of meritorious activity, one particularly well suited to the religious needs of the laity.

Ngondro

Ngondro (pronounced nundro) means “something that precedes” and refers to practices used to clear away negativity and accumulate merit in preparation for higher Vajrayana practices, and to cultivate right view. Ngondros vary from lineage to lineage, but usually consist of a series of four practices that include rituals, prayers, and physical and mental methods of purifying body, speech, and mind. The first ngondro is taking refuge in the form of full-body prostrations before an image, altar, or painting to discipline the body and heart. The second is the visualization of Vajrasattva, a buddha associated with purification of thoughts and actions, and the recitation of his hundred-syllable mantra. The third is a mandala offering, a sequence of ritualized offerings of saffron rice ornamented with coins, jewels, and semiprecious stones arranged on a round plate. These are visualized by the practitioner as containing the universe and all its most desirable things, which are offered to the buddhas and bodhisattvas. The fourth ngondro is called guru yoga. In this practice, a student visualizes their teacher as an embodiment of the Buddha and the wisdom of all the teachers in a practice lineage, a process that involves the memorization and recitation of lengthy litanies.

Ngondros are considered only preliminary, but even so, they are not for the faint of heart. Depending on the lineage, the first three are performed 100,000, 108,000, or 111,000 times, and guru yoga is done in 1,000,000, 1,080,000, or 1,110,000 repetitions. Needless to say, not all Americans in the Tibetan Buddhist community take up ngondro practices, or may do so only sporadically. Ngondros are, however, fundamental for students who want to advance to the primary forms of Vajrayana practice. Over the course of several years, students will routinely “work on their ngondro.” Those Americans who become lamas repeat ngondros periodically in the course of their lifetime practice.

Sadhana

Sadhana, or “means of accomplishing,” is a form of Vajrayana meditative practice based on visualizations. It is a ritual procedure during which a practitioner visualizes one or another fully realized buddha or bodhisattva, the choice depending on his or her teacher and lineage. All sadhanas serve as tools to accomplish the same end—the cultivation of total liberation or fully enlightened consciousness by identifying body, speech, and mind with the attributes of a fully realized being.

The procedures in performing a sadhana can be summarized in three basic steps. The first is the taking of refuge and the dedication of merit resulting from the performance of the sadhana to the enlightenment of all beings. The second step, which is the core of the practice, is the visualization of a buddha or bodhisattva in detail—the palace or mandala in which they reside; their apparel and ornaments; and their posture and characteristic gestures, which are called mudras. Throughout a visualization, a practitioner also chants mantras identified with the buddha or bodhisattva in question.

One can get a sense of the visualization process in the following excerpts taken from a Medicine Buddha sadhana offered at an empowerment by Geshe Khenrab Gajam at Osel Shen Phen Ling, a Gelugpa center in Missoula, Montana, in 1990.

In the space in front of you is the divine

form of Guru Medicine Buddha. He is seated

on a lotus and moon cushion. His body is

in the nature of deep blue light, the color of lapis lazuli.

He is very serene and adorned with silk robes and magnificent

jewel ornaments.

Guru Medicine Buddha’s right hand rests on his right knee,

palm outward in the gesture of giving realizations. His left

hand rests in his lap, holding a nectar bowl of medicine that

cures all ills, hindrances and obstacles.

Later in the sadhana, the visualization process continues, but with an emphasis on the purification of all obstacles on the path to enlightenment and a vision of the clarity of fully awakened consciousness.

From the heart and holy body of the

King of Medicine, infinite rays of light pour down completely

filling your body from head to toe. They purify all your

diseases and afflictions due to spirits and their causes, all

your negative karma and mental obscurations. In the nature of

light, your body becomes clean and clear as crystal.

......................................................

At the heart of Medicine Buddha appears a lotus and moon

disc. Standing at the center of the moon disc, is the blue

seed-syllable OM surrounded by the syllables of the mantra.

As you recite the mantra, visualize rays of light radiating

out in all directions from the syllables at his heart. The

light rays pervade the sentient beings of the six realms.

Through your great love wishing them to have happiness, and

through your great compassion wishing them to be free from

all sufferings, they are purified of all diseases,

afflictions due to spirits and their causes, all their

negative karma and mental obscurations.9

The third and concluding step is sometimes referred to as the “carryover practices.” In this step, the practitioner dissolves the visualization completely, rests in the awakened state evoked in the course of practice, and prepares to carry the insight into everyday life. To conclude the sadhana, he or she dedicates the merit accrued from performing it to all living beings.

There are a relatively small number of Americans, several thousand perhaps but certainly not more than ten thousand, who routinely perform this kind of sadhana expertly. The ngondros and the three-year, three-month retreat are daunting disciplines that tend to select out all but the most committed. Those Americans who have become accomplished at performing them, however, hold the distinction of being among the first generation of native-born teachers of Tibetan Buddhism in this country.

The process of establishing Tibetan Buddhism in America has been undertaken by numerous teachers, both Tibetan and American. Most are religious teachers at work within particular communities, in dharma centers or monasteries, or in more public educational facilities like Naropa Institute. A number of them are also academics, some of whom work as scholars and professors in research universities. Given the circumstances that surround Tibet, much of their work is traditional in character, if not conservative, devoted to the collection, preservation, and interpretation of texts and to perpetuating the teachings. Some have taken up work that is more directly political. A number of teachers, however, have made a conscious attempt to cast Tibetan Buddhism in western terms and are among the communities’ most prominent innovators.

For instance, Tarthang Tulku was among the first of the pioneering generation of lamas to recast elements of the Tibetan tradition, including its visualization techniques, into essentially secular terms. His Time, Space, Knowledge Association, which was founded in the 1970s, has its own body of texts and a small but dedicated following.

Chogyam Trungpa’s Shambhala Training is a more well-known secular path for the cultivation of contemplative living. The inspiration for Shambhala Training came to Trungpa in a series of dreams and visions in the early 1980s. As a result, they are considered terma, a form of teachings thought to be hidden centuries ago by the great sage Padmasambhava, only to be revealed at a later date that was determined by karma. Thus Trungpa is considered to be a terton or treasure-finder, who discovers and reveals hidden teachings. The details of Shambhala Training are closely held by the practice community, but its basic elements are outlined in Trungpa’s book, Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior, published in the 1980s. Shambhala Training is currently cultivated in classes offered by Shambhala teachers in various locations across the country. It is considered a path in its own right, but many Shambalians go on to study Vajradhatu, the more traditional form of practice offered in Shambhala International.

Two Americans, Lama Surya Das and Robert Thurman, have also emerged as innovative voices in the Tibet community. Surya Das (Jeffrey Miller) is a religious teacher primarily associated with the Nyingma tradition, but, like Chogyam Trungpa, he was also ordained in the nonsectarian rimed movement. He first encountered Tibetan Buddhism when traveling in India in the 1960s and ’70s. He studied with lamas there for a number of years. Then in 1980 he traveled to France, where he completed two three-year, three-month retreats under the guidance of Dudjom Rinpoche and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, renowned lamas of the Nyingma lineage.

Over the course of the 1990s, Surya Das joined other leading native-born teachers from a range of traditions at the forefront of a movement to consciously forge American forms of the dharma. He was instrumental in organizing the Western Buddhist Teachers Network, a loose affiliation of Vajrayana, Zen, and Theravada teachers from America and Europe who are wrestling with the challenges of adapting Buddhism to the West. In 1991, he established the Dzogchen Foundation in Cambridge, Massachusetts to serve as his home base. Dzogchen, which means “natural innate perfection,” is a Zenlike form of meditation considered the highest form of practice in the Nyingma tradition. In the late ’90s, he published Awakening the Buddha Within: Tibetan Wisdom for the Western World, which is among the most accessible in a new generation of books designed to introduce Buddhism to Americans.

Robert Thurman, co-founder of Tibet House and professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University, probably has the highest public profile of any American Buddhist, other than celebrities such as Richard Gere. In 1997, Time magazine named him one of the twenty-five most influential Americans. Like Surya Das, Thurman traveled to Asia in the early ’60s, when he was ordained a Buddhist monk by the Dalai Lama. After four years of practice and a return to the United States, he relinquished his vows and entered the academic field of Buddhist Studies. Like others in his generation whose personal commitment to monasticism waned, he married and began to raise a family, seeing lay life as a way to follow the bodhisattva path. “I didn’t make that much progress as a monk,” he told the Utne Reader in 1997. “I learned a lot more after coming back and having to deal with the nitty-gritty. It’s comparatively easy to be a monk in a quiet monastery, but the bodhisattva tries to engage with all the noise of the world.”10

In most respects, Thurman is in a class of his own—a well-respected scholar, confidante of the Dalai Lama, and provocative public Buddhist intellectual. Despite his own decision to leave the Gelugpa order, he is an outspoken defender of monasticism who sees the establishment of the monastic traditions of Asia in the West as a prerequisite for the successful transmission of the dharma. He is also a well-known advocate for what he calls “the politics of enlightenment,” which he outlined in his 1998 book, Inner Revolution: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Real Happiness.

As its title suggests, Inner Revolution is a manifesto for an exuberantly American Buddhism. Much of its power comes from Thurman’s ability to tap into an idealistic strand in American culture that can be traced back to the revolutionary period and to link it to ’60s-era politics, giving them both a distinctly Mahayana Buddhist twist. Much of the book’s appeal for American readers is its activist, democratic, social agenda and its affirmation of the importance of the individual. “History’s enlightenment movements tell us we can transform ourselves and our world,” Thurman writes.

We can start by allowing that it might be possible to make an enlightened society, one individual at a time, starting with the obvious: ourselves. If, once we enter into the process of enlightening ourselves, we find it possible to help other people move in the same direction, so much the better.… If we don’t see the whole move into a buddhaverse manifestation in our lifetimes, at least we will have been part of the potential solution rather than of the problem.11

But in his sweeping interpretation of global history, Thurman also envisions the twenty-first century as a time when the “outer modernity” of the West can be transformed by the “inner modernity” of Buddhist Asia. Ultimately, he suggests nothing less than that a path of enlightenment first discovered by America’s founding fathers in their revolt against the British can be fulfilled by the dharma, which was brought to its highest development in Tibet as a science of spirit and a model for enlightened society. Presenting the idea that the American revolution invested kingly power in the individual, Thurman concludes that:

We must reaffirm the democratic mission to restore a piece of the jewel crown of the natural royalty of every individual to every person on this planet, letting the authoritarian personalities of dictators and dictated melt in the glow of the human beauty and creativity released by freedom.12

The idealism expressed by Thurman and others played an important role in raising the public profile of Tibet in America in the 1990s. But the future of Tibetan Buddhism in this country depends on its lamas in exile and its American teachers, the dedication of their students, and, in large part, the future of Tibet. Some lamas express the conviction that the invasion by China was determined by karma to disseminate the dharma worldwide. By the 1990s many had lived and taught in the West for most of their lives. However, a new generation of Tibetan teachers were moving into prominence, who did not share with their elders the experience of living in old Tibet and were more in tune with the West. If Tibet becomes free once again, many lamas and other Tibetans in exile will no doubt be drawn home to build a new society. But even if that occurs, Tibetan Buddhism will remain a permanent part of the American Buddhist landscape, with its uniquely rich and highly distinctive forms of philosophy and practice.