Immigration and the complex social forces associated with it gave rise to the Japanese Jodo Shinshu community, which through the trials and errors of successive generations has struck a balance between being ethnic Buddhist and mainstream American. Immigrants formed the original Nichiren groups in this country, and they still contribute to the rich multiculturalism of Nichiren Shoshu Temple and SGI-USA. Tibetan lamas, whether as alien residents, exiles, or new citizens, are essential to the practice of Tibetan Buddhism and Vajrayana in the United States. And despite the impact of literature in generating interest in Zen in this country, Japanese immigrants were the first practice-oriented teachers. The importance of immigration to Theravada Buddhism in this country cannot be overstated.

Migration has also been the driving force behind the formation of Korean, Vietnamese, and Chinese American communities, which are contributing a variety of elements to the American Buddhist mix. Koreans and Vietnamese have been in the United States in large numbers only since the 1970s. Chinese Buddhists have been part of the religious life of this country since the mid-1800s, although they did not form large, enduring religious institutions until more recently. Korean, Vietnamese, and Chinese Buddhism are all in the Mahayana tradition and thus have much in common, but each draws inspiration from its own regional traditions and folkways.

Historians have yet to focus sustained attention on the religious lives of these groups, so it is difficult to do more than sketch some of the ways they are adapting Buddhism to American society. Buddhism plays an integral role in the formation of personal and social identity. It provides many immigrants and their children with emotional stability and a sense of continuity. As a result, religion in these communities is intimately linked to broader patterns of social and cultural adaptation, generational change, and Anglicization. However, some religious leaders within each of these traditions have reached beyond their respective ethnic groups to make vital connections with American Buddhist converts and contributions to the general development of Buddhism in American society.

Chinese Diaspora Communities

Buddhism has been practiced by Chinese in America since the middle of the nineteenth century, when immigrants from the mainland first arrived in California, or Gold Mountain as it was called in China, drawn by the Gold Rush of 1848. The first social organizations formed by the Chinese were based on kinship and linguistic groups and mutual aid societies. In the absence of regularized diplomatic ties between the United States and China’s Manchu government, these voluntary associations, later consolidated into merchant organizations called the Six (or Seven) Companies, became influential, particularly when anti-Chinese violence flared up on the West Coast in the post–Civil War decades.

For much of Chinese American history, these merchant groups were the primary sponsors of the community’s religious life. The first Buddhist temple in San Francisco was founded by the Sze Yap Company in 1853. A rival company founded the second a year later. Each temple was housed on the top floor of the company’s headquarters, a pattern that can still be observed in older Chinatown temples today. By 1875, there were eight temples in San Francisco. By one generous estimate, there were more than four hundred Chinese temples, often small shacks or home temples, at the end of the nineteenth century across the western states, only a few of which still exist today. The religion practiced in these temples was a complex mixture of Confucian ancestor veneration, popular Taoism, and Pure Land Buddhism that typified Chinese popular religion. Devotion to Amitabha, Kuan Yin, and other bodhisattvas was introduced to this country by Chinese Buddhist pioneers.

Most Chinese Buddhism in this country today is of more recent origin. Chinese immigration was drastically curtailed in the late nineteenth century, and as a result, estimates of the population in the twentieth century have run as low as 150,000 in 1950. But changes in immigration law in the 1950s and ’60s encouraged a dramatic increase. By the mid-1990s, there were well over three quarters of a million ethnic Chinese immigrants in this country, from mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and other centers in the Chinese diaspora around the Asian Pacific Rim. Many arrived as Christians, and some no doubt are nonreligious. But many are Buddhist, and there is no question that they are adding considerably to the complex cultural profile of Buddhism in America.

Some scholars estimate that by the 1990s there were more than 150 Chinese Buddhist organizations in this country, some very small, others extensive. In contrast to the sectarian model prevalent in Japan, most share the tendency of Chinese Buddhism toward doctrinal and ritual eclecticism. A form of practice in most groups is nien-fo, devotional recitation of the names and attributes of the buddhas and bodhisattvas, especially that of Amitabha, who in Japan is known as Amida. In many of these organizations, the taking of bodhisattva vows and the cultivation of compassion are of central importance, and this encourages altruistic social action that can include charity and disaster relief work, maintaining a vegetarian diet, and practicing the ritual release of captive animals. Most groups also practice sutra study and chanting. Few give exclusive emphasis to the kind of sitting meditation associated with Zen.

Aside from these general characteristics, it is clear from the available data that Chinese American Buddhism is also highly diverse. Most organizations serve ethnic Chinese exclusively, but a few have a significant number of other members and participants. Some are monastic in orientation, while others, to give free rein to the religious aspirations of laity, have no monastic sangha at all. A considerable variety is found within Chinese American Buddhism today, with varying elements drawn from the national traditions of Burma, Vietnam, and Tibet. There are also important class variables at work. Some temples serve working-class Chinese living in urban Chinatowns, while others address the needs of doctors, engineers, entrepreneurs, computer programmers, and other professionals who are more likely to live in suburban communities. A number of Chinese temples and associations are directed by nuns, whose constituencies are largely composed of laywomen. Brief sketches of a few organizations can only suggest the richness and complexity of the forms of Chinese Buddhism currently thriving in this country.

Eastern States Buddhist Temple of America

Located in the heart of New York’s Chinatown, Eastern States temple was founded by James Ying (My Ying Hsin-jiu) and his wife Jin Yu-tang. In 1963, it became the first New York Chinese American organization with a monk in attendance, and it subsequently played an important role in bringing to this country many of the Chinese monks currently presiding over temples in New York City. The temple is also familiar to many tourists because its street-level shrine room, bookstore, and museum are a frequent stop on the city’s guided bus tours. Other areas of the temple remain closed to visitors. In 1971, Eastern States opened Temple Mahayana as a retreat in the Catskill Mountains north of the city. Several monks live in residence at the Temple and laypeople use it as a retreat facility. On special festival days, buses shuttle hundreds of pilgrims to Temple Mahayana from New York City.

Cheng Chio Buddhist Temple

This temple in the Pure Land tradition was founded in 1976 by Fa Hsing, a Buddhist nun from mainland China who had been forcibly laicized by the communist government in 1956 and put to work in a factory. She eventually emigrated to Hong Kong, where she remained for seventeen years before moving to Canada. At the invitation of the Eastern States Buddhist Temple, she came to New York City in 1973. Despite the objections of some area monks, she soon established her own temple in a rented apartment, which she later moved after raising funds to purchase a three-story building. By the early 1990s, Cheng Chio temple had more than a hundred members, including five resident nuns. About 80 percent of the members are women. Each Sunday they gather to chant, then share a vegetarian lunch. Once a month they celebrate a liturgy for Bhaisajyaguru, the Medicine Buddha. The temple also conducts ancestral rites, weddings, and funerals.

Buddhist Association of Wisdom and Compassion

This lay association in Akron, Ohio was founded in the late 1980s by Ted He Tang, a medical doctor born in Taiwan who has lived in the United States for many years. The group has about fifty members in the Akron area, with branches in Detroit, Columbus, and Cleveland, and between 400 and 500 participating members nationwide. It has no ties to a monastic sangha and no formal temple organization. Members consider these to be distortions of the original teaching of the Buddha, which they understand to be the cultivation of wisdom and compassion and social service. Meetings are held either in private homes or in rented spaces. Members engage primarily in the Pure Land practice of chanting the names of Amitabha. Their social service consists of making donations of money and goods and providing health care for area poor and needy. They also chant sutras for the ill and deceased in members’ families, which in case of serious illness is done on a twenty-four-hour basis.

Tzu Chi Foundation

The Buddhist Compassion Relief or Tzu Chi Foundation was founded in Taiwan in 1966 by Master Cheng Yen, her followers, and five disciples. They began their charitable work with daily donations from members and the proceeds from the sale of baby shoes sewed by the disciples. Like many other charities, Tzu Chi channels religious sentiments into philanthropic work, the spirit of which is captured in its slogan, “To relieve with compassion, to give with joy.” Since its founding, the movement has attracted more than 4 million members located in Chinese diaspora communities worldwide. There are about 16,000 members in the United States, affiliated with chapters located in 11 states. The Tzu Chi Foundation has done extensive disaster relief work around the world. In this country, it runs an academy, a publishing concern, and a free clinic in Alhambra, California. It also actively promotes bone marrow transplants and recruits donors for patients in need. Since 1993, it has maintained the Taiwan Marrow Donor Registry, which is now the third largest registry in the world and the largest in Asia. In Canada, Tzu Chi joined forces with the Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre in developing a clinical facility devoted to research and public education in alternative and complementary medical care.

Most Chinese Buddhist organizations operate within the boundaries of their ethnic groups, but a number are also active in the broader Buddhist community. Most convert practitioners seem not to be aware of the many contributions these groups are making to the creation of American forms of the dharma. The work of some of them is carried on at the leadership level of different ethnic and national immigrant Buddhist communities. But they all, in one way or another, have been building bridges between American Buddhists and Buddhist communities overseas.

Ch’an Meditation Center

The Ch’an Meditation Center is part of a network of organizations founded by Sheng-yen, a Ch’an master who is currently the abbot of Nung Ch’an Monastery and the founder of the Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies and the International Foundation of Dharma Drum Mountain, all in Taiwan. It operates both as a small monastery where fully ordained monks and nuns live in accord with the vinaya and as a public study and practice center. Its constituency consists largely of Chinese Americans, but includes other ethnic groups as well, among these many European Americans who attend classes and lectures on Buddhist scriptures and philosophy and engage in chanting, liturgy, and sitting meditation.

Sheng-yen was born in rural mainland China in 1931 and became a monk at the age of thirteen. In 1949, he fled the mainland for Taiwan, where he continued to practice and study. He eventually earned a Ph.D. in Buddhist literature from a Japanese university and received dharma transmission in the 1970s. He started the Ch’an Meditation Center in 1976 as a meditation group at the Temple of Great Enlightenment in the Bronx, where the Buddhist Association of the United States (see below) has its headquarters. Within two years, the group established its own center, which is now located in Elmhurst, New York. Sheng-yen frequently travels between Taiwan and the United States, but also has students in the United Kingdom. He is highly regarded in international Ch’an/Zen circles and is the author of a number of books and a translator of sutras. His stature is such that he was invited to engage in a public dialogue with the Dalai Lama in New York during the latter’s spring 1998 American tour.

Fo Kuang Buddhism

Fo Kuang Buddhism is perhaps the largest Chinese Buddhist movement in this country. It was founded in 1967 by Master Hsing Yun, a prominent figure in the ongoing revival of Buddhism in Taiwan. Born in Chiangsu province on the mainland in 1926, Hsing Yun became a monk at the age of twelve and was fully ordained in 1941. Seven years later, he followed the Nationalist government to Taiwan. There he witnessed the emergence of a booming economy and experienced firsthand the kind of social transformation that accompanies rapid economic progress. This prompted him to redefine elements of the Chinese tradition to address the needs of daily life in an increasingly consumer-driven, urban, and industrial society. Hsing Yun’s philosophy has been described as “humanistic Buddhism,” in which the Pure Land tradition has been recast as an optimistic vision for the betterment of human society. The tenor of these ideals is expressed in the name by which the movement is known in this country, the International Buddhist Progress Society.

The international headquarters of the society is at Fo Kuang Shan (“Buddha’s Light Mountain”), a monastery in Taiwan, where the movement also has sixteen other affiliated temples. Temples or associations are also found in South Africa, France, Germany, Canada, and in Asian countries around the Pacific Rim. Buddha’s Light International Association, the lay wing of Fo Kuang Buddhism, was inaugurated in 1991 and reports one million members, mostly ethnic Chinese, in fifty-one countries.

Hsi Lai, or “Coming to the West,” temple is an extensive monastic compound in the Los Angeles metropolitan area that serves as the American headquarters for Fo Kuang Buddhism and its affiliates in San Francisco, San Diego, Dallas, Houston, Austin, Las Vegas, Kansas City, and New York. In addition to religious programs and retreats, these centers offer classes in Chinese language and literature, martial arts, painting, and singing. Most members are ethnic Chinese, but Caucasians, African Americans, and others are encouraged to participate and become members. Some have taken lay precepts. Hsi Lai temple also plays a role in American Buddhist ecumenism by frequently helping to organize events such as the 1997 Buddhism Across Cultures conference, co-sponsored by the Buddhist Sangha Council of Southern California and the American Buddhist Congress.

In late 1996, Hsi Lai became embroiled in scandal after hosting an event that set off a controversy about fund-raising by the Democratic National Committee. Many Asian Americans saw in the press reactions—which included sly, winking references to Charlie Chan and hand-wringing about Asian money on the Potomac—a renewal of the “yellow peril” rhetoric of the last century. Others expressed bewilderment about the confusing ways Americans juggle courtesy, good will, political support, and money. The Los Angeles Times quoted one Hsi Lai temple nun who dismissed the affair as “a storm in a teacup,” but Hsing Yun himself took a darker view. “How could something that is a good thing turn into something that is a bad thing?” he asked. “The more we Asians try to participate, the more we get criticized.… We asked ourselves, ‘What is our mistake?’” he told one reporter. “The only mistake I can think of is that we were Asian.”1 The cast of characters involved in the controversy, their varied motives, and the details of the Senate investigations are not of the essence here. But for Fo Kuang Buddhists, the funding controversy was a powerful, if painful, wake-up call to how race, religion, money, and power can be a volatile mix in the American political mainstream.

Dharma Realm Buddhist Association (DRBA)

The Dharma Realm Buddhist Association is the Chinese Buddhist group most intimately connected to the broader convert Buddhist community. It was founded by Master Hsuan Hua, who was born in Manchuria and taught in Hong Kong before coming to the United States. He arrived here in 1962 at the invitation of several of his Chinese disciples living in San Francisco. Like Shunryu Suzuki and Taizan Maezumi, he soon began to reach beyond his immediate circle to teach European American students interested in Buddhism in the late 1960s. But from the outset, Hsuan Hua emphasized the importance of the monastic precepts as the foundation for spiritual life, which appealed to many students who were disaffected with the excesses of the counterculture. In 1968, five of his American disciples, three men and two women, received full ordination at Haihui monastery in Taiwan, forming the core of what would later become DRBA. Over the next two decades, full ordinations were held in this country at DRBA centers, first at Gold Mountain Dhyana Monastery in San Francisco and later at its new headquarters at the Sagely City of Ten Thousand Buddhas in northern California.

Hsuan Hua, who died in 1995, charged DRBA with a fourfold mission. A first priority was to build a properly instituted monastic sangha of fully ordained, precept-holding monks and nuns. A second was to develop a body of able translators to make the entire Buddhist canon available in English and other western languages. Hsuan Hua was also an educational reformer. His vision of fusing traditional Buddhist values with innovative education has inspired the DRBA to build schools and produce educators to serve both Buddhists and the broader American community. Hsuan Hua also placed a strong emphasis on interfaith dialogue, a goal that DRBA now pursues with people of other religious faiths and with critical thinkers in the natural sciences.

Throughout his long teaching career, Hsuan Hua drew disciples from both West and East. Students from a wide range of cultural and religious backgrounds now live and work together in DRBA’s institutions, which include ten monasteries in the United States and Canada, an elementary and secondary school, Dharma Realm Buddhist University, and the Institute for World Religions in Berkeley, California. At the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, there are about 350 full-time residents, including 150 precept-holding monks and nuns, families, and live-in students from America, Europe, and the Asian Pacific Rim. This environment fosters face-to-face relations and creative exchanges between Asians and westerners, monastics and laypeople. Dharma Realm Buddhist Association holds a unique place in American Buddhism and in the vibrant, polyglot Buddhist community of the San Francisco Bay area.

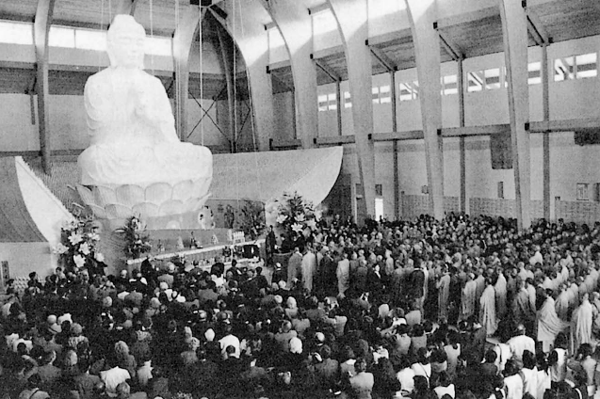

Under the leadership of C. T. Shen, the Buddhist Association of the United States has developed an extensive complex for practice and scholarship at Chuang Yen monastery north of New York City. The Great Buddha Hall, pictured above, was formally dedicated in the spring of 1997 by the Dalai Lama in the course of a three-day-long ceremony.

BUDDHIST ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES

Buddhist Association of the United States (BAUS)

BAUS is the largest Chinese Buddhist organization in metropolitan New York, founded in 1964. Its approximately 700 members tend to be well-educated, Mandarin-speaking Chinese, most of them first-generation immigrants from Taiwan. The headquarters of BAUS is at the Temple of Enlightenment in the Bronx, but the organization also maintains Chuang Yen monastery in rural Kent, New York, about an hour north of the city. Construction of the 225-acre monastery began in 1981. It now includes residences for monastics and lay guests, dining facilities, an extensive library of Buddhist texts, and practice halls situated around Seven Jewels Lake, a small body of water in which stands a 12-foot-high statue of Kuan Yin. The centerpiece of Chuang Yen is the Hall of Ten Thousand Buddhas Encircling Buddha Vairochana, which has a seating capacity of 2,000 and a 37-foot statue of a seated Buddha, the largest in the western hemisphere. It was formally dedicated by the Dalai Lama in three days of ceremonies in May 1997, after which His Holiness conducted several days of teachings for the Buddhist community.

Chia Theng Shen is the major force behind BAUS. Born in Chekiang, China in 1913, Shen spent many years in manufacturing and international trade in Asia. He moved with his family to the United States in 1951 and started a shipping business. In 1972, he became the chairman and CEO of American Steamship Company until his retirement in 1980. Since arriving in this country, the Shens have been important philanthropists in the Buddhist community, donating land in the Bronx and Kent to BAUS and acreage in Woodstock, New York to Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, the monastery that is the North American seat of the Gyalwa Karmapa. C. T. Shen also donated the land for the Buddhist Text Translation Society in San Francisco, whose work is carried on by the monastic community of the DRBA.

Shen is also a scholar, public lecturer, and authority on the Diamond Sutra, an important text in east Asian Buddhism known for its penetrating analysis of nondualism, impermanence, and emptiness. His understanding of Buddhism’s contribution to America is suggested in the address “Mayflower,” which he gave on a number of occasions to commemorate the bicentennial in 1976. In the speech, he likens the Mayflower crossing, a charter event in American history, to a verse from the Diamond Sutra, which he considers the charter of the American Buddhist community.

All the world’s phenomena and ideas

Are unreal, like a dream,

Like magic, and like a reflected image.

All the world’s phenomena and ideas

Are impermanent, like a water bubble,

Like dew and lightning.

Thus should one observe and understand

All the world’s phenomena and ideas.

For Shen, the power of the Diamond Sutra as what he called “our Mayflower” is in the wisdom it teaches about realizing a luminous and compassionate state of mind unlimited by the dualistic thinking that gives rise to confusion, hatred, and strife. “This service will soon be over. It is impermanent. Tomorrow your recollection of this occasion will be nothing more than a dream. It is unreal,” he told a New Hampshire audience.

But I hope my message has boarded you onto your own Mayflower. Please carry this message to your family, friends, and the whole nation. Let us sincerely hope that in the tricentennial year, your children and your children’s children will meet here again in a society where lovingkindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity prevail.2

A Korean Buddhist Minority

Korean Buddhism is entering this country in two distinct but familiar ways. The first is through the establishment of traditional temples in Korean immigrant communities in major cities—New York, Chicago, Atlanta, and, most prominently, Los Angeles, where there is an extensive Koreatown in the center of the city. The second is through Korean immigrants, who have been teaching for over three decades in the convert community.

Most Korean immigrants have arrived in this country as Christians. Of the approximately 150,000 Koreans in the Los Angeles area in 1988, only an estimated 10 to 15 percent identified themselves as Buddhist. At this time, there were about 15 Korean Buddhist temples in southern California, but an estimated 400 Christian churches serving the immigrant community. In the late ’80s, the abbot of the Kwan Um Sa temple in Los Angeles estimated that there were 67 Korean Buddhist temples nationwide with an active membership of 25,000. Most of these temples conducted services in Korean and were devoted to addressing the needs of first-generation Korean immigrants.

Korean temples began to appear in major American cities as immigration from Korea rapidly increased in the early 1970s. The first temple, Dahl Ma Sa, was established in Los Angeles in 1973. Most temple practice centers around pophoe, a Sunday service that consists of scripture reading, ceremonies, chanting, and a sermon. Services are not considered obligatory, so attendance, which tends to run from fifty to one hundred people each Sunday, reflects only a small portion, perhaps as little as a fifth, of a temple’s formal membership. Greater numbers regularly attend special festivals such as the Buddha’s birthday. In contrast to Christian church services, Korean congregational worship is quite informal, with people entering and leaving throughout. Most temples focus on devotional rather than meditative practices because the latter do not appeal to their lay constituency. Some offer members a range of social services such as marriage and youth counseling, hospital visitations, and assistance with negotiating government bureaucracies.

The future of these Korean temples depends a great deal on how they negotiate many problems typical of immigrant religious communities. As of 1990, Korean temples lacked an effective administrative structure in this country. Most were loosely affiliated with the Chogye order, the major monastic organization in Korea. Others were Won Buddhist temples, part of a sectarian movement that began in the first part of this century. Many temple leaders lacked English language skills, which put them at a particular disadvantage in dealing with second-generation issues. Clergy often faced financial difficulties. Lacking the kind of institutional support found in Korea, many needed to work outside the temple, a practice that was often viewed with suspicion by many laypeople. Once in this country, many monks chose to leave the clerical profession to pursue other vocations, a phenomenon that is fairly common in American immigration history.

As is the case with other groups, the links between immigrants in this country and the homeland play a powerful role in shaping the life of the community. The large Korean immigrant community in southern California has experienced a number of peaks and valleys as it has attempted to balance strong attachments to Korea with pursuit of the American dream. Hopes of quick success vanished for many in the mid-1980s with a severe downturn in the Los Angeles real estate market, which effectively trapped many Koreans in this country. At the same time, South Korea rose as an economic tiger, which became for Korean Americans a source of both pride and envy. In the early 1990s, the Northridge earthquake and then the Los Angeles riots, in which Koreatown was severely damaged by arson and looting, left many in the community reeling, questioning the wisdom of ever having left Korea. But by the late ’90s, the tide turned once again as the Korean economy, along with those of the other southeast Asian tigers, went into a tailspin. Katherine Kim, a Korean American journalist, reflects on what she calls the emotional roller-coaster ride experienced by Korean Americans during the 1997 currency crisis. “Sadness rolls in with the loss of pride. It affects ethnic Koreans—whether in America or in Korea—for it is happening to our country, ‘woori nada.’” 3

A number of Korean immigrant teachers have also made an impact in the broader American Buddhist community. Kyungbo Sunim (sunim is Korean for “monk”) is often cited as the first Korean teacher in this country. He visited Columbia University in 1964 and stayed in America for six years, moving from one city to another and lecturing on Korean Buddhism in temporary temples located in rented houses. Upon his return to Korea, one of his disciples, Kosung Sunim, came to America and founded Korean-style meditation centers along the East Coast. Kusan Sunim, an influential Korean Buddhist leader, made his first trip to the United States to inaugurate the Sambo Sa temple in Carmel, California in 1972, a visit that served as the occasion for him to cultivate an American following. Students he gathered on that trip returned with him to Korea to form the core of what later became the International Zen Center at Songgwang Sa temple, an organization that subsequently trained a number of western students, among them Stephen and Martine Batchelor, two Buddhist leaders who primarily work in the United Kingdom but are influential in America.

Two teachers, Samu Sunim and Seung Sahn Sunim, achieved particular prominence in this country in the 1980s and ’90s. Both teach the dharma in the Korean Son Buddhist tradition, a stream of practice related to Ch’an and Zen but often noted as having an earthiness, informality, and humor characteristic of the Korean national tradition. While the teachings and organizations of Samu and Seung Sahn are in some ways quite distinct from those of classical Zen, they and their students are generally seen as a part of the broader Zen movement in this country.

Samu Sunim emigrated to Montreal, Canada in the late 1960s. In 1972, he relocated to Toronto, where he “lived in a basement apartment on Markham Street. It was dark, damp, and cool, but the place was as quiet and as secluded as a mountain cave.” He lived there for seven years, spending much of his time alone, engaged in meditation. During an illness, he was “discovered” by older immigrant women, most of whom had migrated to Canada from the Korean countryside. They cared for him, while he began to hold service for them on Sundays. “Occasionally, I took them to visit other temples in Toronto in order to help them understand the different aspects of world Buddhism,” he recalls. “Buddhism is an endless journey. Buddhists are pilgrims on this endless journey toward the liberation of all. The journey is endless because sentient beings are innumerable.” At some point, however, “it dawned on me that I was on a pilgrimage to the contemporary Buddhist movement in North America.”

Samu Sunim then began in earnest to visit many Buddhist centers while traveling throughout Canada and the United States.

I had a special feeling for every Buddhist place I visited and each Buddhist I met. Their struggle and difficulties in establishing new temples and spreading dharma in the foreign land naturally evoked a great respect and deep appreciation in me. I felt grateful and indebted to them for their dharma work. In those days, I had no particular ambition. I thought I would be living in the basement permanently. Looking back, I feel I was like a humble servant who knelt before a Buddhist monument in the making and enjoyed himself with meditation and prayer.4

Shortly thereafter, he moved from the basement and, together with other Buddhists, purchased a “flophouse” in Toronto, which they converted into a teaching center.

In subsequent years, additional centers were established in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Chicago, and Mexico City, linked together in a modest-sized but vibrant organization called the Zen Lotus Society, today the Buddhist Society for Compassionate Wisdom. Samu Sunim’s interests prompted him to host the Conference on World Buddhism in North America at his temple in Ann Arbor in 1987, at which many prominent leaders, both converts and immigrants, gathered to discuss the challenges they faced in propagating the dharma in the West. He also served on the International Advisory Board for the Council for a Parliament of the World’s Religions held in Chicago in 1993.

Seung Sahn Sunim was born in North Korea in 1927, of parents who were Protestant Christians. During World War II, he was in the underground working for Korean independence from Japan. After the war, he became interested in Buddhism when a friend of his, a monk in a small mountain temple, gave him a copy of the Diamond Sutra. In 1948, he was ordained as a monk and practiced on his own until meeting Ko Bong, a master in the Korean tradition who became his teacher and later gave him dharma transmission. When Seung Sahn came to the United States in 1972, he began to teach in an apartment in the inner city of Providence, Rhode Island, slowly developing a dynamic style by combining sitting meditation, koans, dharma talks, chanting, and prostrations. His fledgling organization soon drew the attention of students at Brown University. In the course of a few years it grew rapidly, and by the early 1980s he was said to be training as many as 1,000 students both in the United States and overseas.

In 1983, Seung Sahn founded the Kwan Um School of Zen. As of 1998, it claimed more than sixty practice centers worldwide, most of them in the United States and Europe, loosely overseen from its headquarters in Cumberland, Rhode Island. As of that date, Seung Sahn had given dharma transmission to seven students, who are now Zen masters in the Kwan Um school. He has also authorized about fifteen senior students, who in the movement are called Ji Do Poep Sa Nims or Guides to the Way, to teach. Among Seung Sahn’s best known works are Ten Gates, which treats the ten koans most frequently used in teaching in the Kwan Um school; Dropping Ashes on the Buddha: The Teaching of Zen Master Seung Sahn, which contains material related to his biography; and The Compass of Zen, an engaging presentation of the Buddhist tradition from the perspective of Zen.

Seung Sahn’s charismatic teaching style has great appeal for many Americans. He has called his enigmatic method of teaching “Don’t Know Zen,” which evokes the example of Bodhidharma, the first Chinese patriarch in the Ch’an tradition of China. In one ancient tale, Emperor Wu of Liang, who was affronted by Bodhidharma’s apparent impudence, angrily demanded to know who he was. Interpreters of Ch’an have long taken Bodhidharma’s reply, “Don’t Know,” to be a reference to the Buddha mind that exists prior to all thinking and is luminous in its emptiness. Seung Sahn has also encouraged experimentation in Americanizing Buddhism, a liberty that many of his students value highly and find to be a source of genuine creativity. “Many people have fixed ideas about what is American,” he noted in an address at the second annual congress of the Kwan Um school in 1984, “but in fact there are countless ideas.”

Some of these ideas lead to difficulty, and some may help people. If we cling to one idea of what is American, we become narrow minded and the world of opposites will appear.… The true American idea is no idea. The true American situation is no situation. The true American condition is no condition.… The direction and meaning of our school is to let go of your opinion, your condition, your situation. Practice together, become harmonious with each other, and find our true human nature.”5

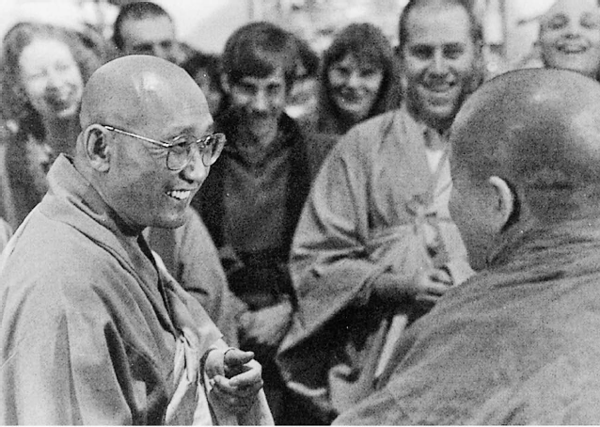

Seung Sahn, pictured here with students from his Kwan Um School based in Rhode Island, is among several influential Korean Buddhist teachers who have been at work in the convert community since the early 1970s. A distinct tradition in the Ch’an school of Buddhism, Korean Buddhism as taught by Seung Sahn is considered part of the multifaceted Zen tradition flourishing in the United States. KWAN UM SCHOOL OF ZEN

By the late 1980s, Seung Sahn had begun to turn over much of the teaching in the Kwan Um school in this country to his students as a way to foster Americanization. “Before, everybody was my student,” he noted in 1989, “but now the Ji Do Poep Sa Nims have their own students. Now the Ji Do Poep Sa Nims will decide the Kwan Um School of Zen’s direction; they understand American mind better than me. I taught only Korean style Buddhism; now the Ji Do Poep Sa Nims are teaching American style Buddhism.”6

Vietnamese Exile Communities

In the years after the defeat of the United States in Vietnam and the fall of Saigon in 1975, well over a half million Vietnamese arrived in America. Most came as part of an “acute” rather than “anticipatory” refugee movement, meaning that their flight was unplanned and chaotic, a response to the rapid collapse of American military power in southeast Asia. A few were airlifted by helicopter from the roof of the besieged American embassy in Saigon. The vast majority, however, began long, often tortuous journeys to this country through squalid refugee camps in southeast Asia and by sea as boat people in overcrowded floating death traps.

Andrew Lam, a Vietnamese American author and journalist who arrived in this country as a young boy, recalls the sense of tragedy and loss that for decades pervaded Vietnamese exile communities. “The saddest date in the Vietnamese exile calendar was, of course, April 30, 1975, known as ‘Ngay mat nuoc’—the day of national loss.”7 The Vietnamese exile narrative “tells of families torn apart; fathers lost in communist gulags, children drowned at sea, sons executed by Viet Cong in front of distraught fathers, wives and daughters raped by Thai pirates on crowded boats, sons and daughters abandoning senile mothers and now wracked by sadness and guilt.” In Vietnamese coffee shops in San Francisco and other exile communities in this country, “songs with titles like ‘Mother Vietnam, We Are Still Here,’ and ‘Those Golden Days in Vietnam’ still echo nostalgically on the speakers.”

Despite the trauma of defeat and the refugee experience, the Vietnamese have been successful at negotiating the obstacles on their path to Americanization. A new era in the Vietnamese community began in 1995 when President Clinton normalized relations between the United States and Vietnam. At about the same time, a second generation began to come of age for whom Vietnam represented less a tragic element in the past and more a future opportunity. The 1990s saw the emergence of a new phenomenon Lam calls “a reverse exodus.” “The gap between father and son, between generations, grows wider,” Lam writes. “Ironically, while my father’s generation find it harder to return home, we children have returned many times, searching for ways to help and influence the future of our homeland.” Despite continued political and religious repression in the homeland, “Vietnam and America, the two divergent ideas, are converging. I see an old legacy ending and the hyphen of my identity stretching like a bridge across the deep blue sea.”

The new era in the Vietnamese American community is also reflected in the maturation of Vietnamese religious institutions, some Roman Catholic, most Buddhist. As in Theravada ethnic communities, many Vietnamese temples were first established in suburban homes or small storefronts and mini-malls across the country. More recently, grand new edifices that reflect the social and economic confidence of the community have been erected in many places, from Minneapolis to Oklahoma City. By one count, there are now more than 150 Vietnamese Buddhist temples in this country.

Most Vietnamese settled in California, where they have become an integral part of a new Pacific Rim ethnic, racial, and religious mosaic in the making. Many are located in northern California and have found the computer industry of Silicon Valley, which many Vietnamese refer to as “the Valley of Golden Flowers,” to be an excellent vehicle for upward mobility.

Thanh Cat temple, located close to Stanford University and affluent Palo Alto, and in the midst of the freeways of Silicon Valley, epitomizes in its history the saga of this country’s Vietnamese. Thich Giac Minh, abbot of the temple, arrived in the United States just after the war ended. Working as a licensed acupuncturist, he donated his earnings, as did others in his community, to aid refugees. Construction of Thanh Cat temple was repeatedly deferred so that surplus funds could be used to sponsor boat people to come to this country. After a few years, however, the situation had stabilized and construction could begin. Thanh Cat was completed in 1983, and is now one of a number of temples in the area offering a range of religious services—Sunday gatherings, daily chanting sessions, meditation, and ceremonies to commemorate ancestors. But Mrs. Luong Nguyen, who with her husband is a long-time lay supporter of the monks and nuns of Thanh Cat, also notes that “The temple is more than a place of worship.… We come here to feel anchored. We share news about our lives and we support each other … and if possible, we get our children married.”8 Thanh Cat also serves as the headquarters and training center for monks and nuns affiliated with the Vietnamese Buddhists of America, an organization of about one hundred ethnic temples scattered across the country.

Chua Vietnam, which occupies an apartment building in central Los Angeles, was founded in the wake of the fall of Saigon as a refugee center. It is the oldest of the Vietnamese Buddhist temples in California, but many more are now found to the north in the San Francisco Bay area and to the south in Orange County, as well as elsewhere around the country. DON FARBER

In nearby San Jose, Chua (Temple) Duc Vien is among a number of temples in this country run by Vietnamese nuns. Dam Luu, its head, operated a home for war orphans in Vietnam before the fall of Saigon. After the communist takeover, she eventually escaped on a small boat with 200 other people, making a grueling six-day trip, with no food or water, to Malaysia. By 1980, Dam had found her way to San Jose, where she rented a small house to serve as a temple. Over the course of the next decade, she accumulated $400,000, earned from recycling newspapers, cans, bottles, and cardboard and from donations made by laity, which she used to make a down payment on a new temple. In the early 1990s, Chua Duc Vien, a million-dollar, 9,000-square-foot temple, opened with nine resident nuns who live in a very modest wood-frame house next door.

One of the most vibrant Vietnamese communities in this country is in Orange Country, California, about twenty miles south of Los Angeles. As recently as 1975, this area of Westminster and Garden Grove was little more than a cluster of aging mobile home parks and auto repair shops set in the midst of strawberry fields. But in the past two decades it has been transformed by the Vietnamese, many of whom arrived in this country through a refugee center at Camp Pendleton, about thirty miles to the southeast. The area of settlement “literally exploded,” Westminster Mayor Chuck Smith told an Asian Week reporter in 1996. “The development there was just unbelievable. It’s been very positive for the city.”9

In the early 1990s, local entrepreneurs began to develop this thriving business district into Little Saigon, which they envision both as a national showcase for Vietnamese culture and as a tourist attraction to draw crowds that visit nearby Disneyland and Knott’s Berry Farm. “The Asian Garden Mall is a mall like no other,” the reporter observed. “On a concrete pedestal near the entrance of the two-story building, a statue of a Happy Buddha extends its arms in warm welcome. Behind it are stone statues of the gods of Longevity, Prosperity, and Fortune.… Saigon, once known as the Paris of the Orient, is, in a sense, thriving here in Westminster.” Tony Lam, a member of the Westminster City Council and a Little Saigon pioneer, is quoted as saying, “Old Saigon is no more, the Communists have seen to that.… We wanted to create something here in America to remind us who we are.”10 Little Saigon’s many restaurants and shopping arcades, its Confucian-culture court and Buddhist-themed mall architecture, reflect a newfound public optimism and confidence among the largest concentration of Vietnamese Americans in this country.

Moreover, tucked within the sprawl of the surrounding communities are at least fourteen temples that reflect stages of development in Vietnamese American Buddhist history. Chua (Temple) Truc Lam Yen Tu, reportedly the oldest temple in the area, is housed in a small, neat brick cottage whose attached garage has been renovated to serve as an intimate shrine room. Chua Hue Quang and its monastic community are housed in a cluster of wood-frame cottages that once sheltered migrant workers. The temple complex contains Little Saigon’s oldest and largest bodhi tree, at the foot of which devotees place incense, fruit, water, and other offerings. By 1997, however, fund-raising efforts for a new temple, including a gala concert featuring Vietnamese pop stars at the Anaheim Coliseum, were underway.

Chua Lien Hoa began as a home temple. After protracted litigation over local zoning ordinances, Dao Van Bach, the monk who heads the temple, converted the original ranch house into a monastic residence. He constructed a new shrine room in a small backyard that also serves as a social space for afternoon tea and a garden for contemplation. During the installation of a fifteen-foot statue of Kuan Yin, a female bodhisattva of compassion, Bach compared her to the Statue of Liberty. “Both are international symbols of love, peace, and democracy,” he noted. “It is this unity of thought that establishes the unbreakable tie between America and her Vietnamese inhabitants.”11 Less than a half mile across town, Chua Vietnam and Chua Duoc Su, the latter run by Vietnamese nuns, are multimillion-dollar edifices completed in the mid-1990s. They serve Orange County Buddhists both as vital religious centers and as testimonies to the accomplishments of the entire community.

The civic boosterism that is a part of the Vietnamese coming-of-age in America can, however, disguise persistent tensions within the community. Emotions still run very high about a wide range of homeland issues. Political, religious, and economic relations between Vietnamese Americans and Vietnam are likely to remain complex, sometimes volatile, for years to come, like the continuing passionate concerns of Cuban exiles in Miami about issues in the Caribbean. On the domestic scene, many elderly Vietnamese suffer deeply from the emotional scars of their exile, never having adjusted to the freeways and suburban sprawl of California.

It also remains to be seen how Vietnamese Buddhism will fare among the younger generation for whom the American way of life is second nature. Reports of temple life are often studies in contrast. The Los Angeles Times reported on a 1991 ceremony for members of Vietnamese families held at Chua Vietnam. While eight monks in saffron and yellow robes prayed, young people milled about eating box lunches and listening to soft rock music. Many elders are concerned about how America’s free-wheeling, consumer-driven lifestyle is eroding the deference and respect Vietnamese children have traditionally held for their elders. Ton-That Niem, a Cerritos, California psychiatrist, notes, “The older generation is trying their best to keep traditional values going.… There’s always a kind of conflict. We try our best and be flexible. I believe with love we can do it.”12

Nam Nguyen, editor-in-chief of Viet Magazine, a San Jose-based bilingual publication often called the Vietnamese Newsweek, expressed concerns about both the erosion of traditional values and the loss of ethnic identity. “The way I see it, we’ve passed the survival phase and we’re now a thriving overseas community entering our entrepreneurial age,” Nguyen told Andrew Lam of Jinn, the online magazine of the Pacific News Service. “What I worry about is the second-generation Vietnamese Americans who are both smarter and more privileged than their parents but may not be driven in the same way. I wonder whether they will simply meld into American life or retain their ethnicity.… We need artists, writers, social scientists to balance out our preoccupation with the high tech field. Maybe the new generation will fulfill this need.”13

Over the course of several decades, a number of Vietnamese Buddhist leaders have reached beyond their ethnic group to make a significant impact on the broader American Buddhist community. Among the earliest was Thich Thien-An, a monk in the Vietnamese tradition who also received training in the Rinzai tradition of Japan. He arrived in southern California in 1966 as an exchange professor at the University of California at Los Angeles. His students there encouraged him to teach Buddhist meditation, which led him to found the International Buddhist Meditation Center (IBMC) in Los Angeles in 1971. After the fall of Saigon, when Vietnamese began to enter the United States in large numbers, IBMC devoted much of its energy to refugee issues. As a result of his twofold interests, Thich Thien-An was instrumental early on in building bridges between the American convert and Vietnamese Buddhist communities. He died in 1980, but his progressive legacy continues in the meditation center he founded, now under the direction of Karuna Dharma, said to be the first American woman to be fully ordained as a bhikkhuni. IBMC remains at the center of the complex, multiethnic, multinational Buddhist world unfolding in Los Angeles today.

Thich Nhat Hanh, another Vietnamese monk, has a stature in the American Buddhist community comparable only to that of the Dalai Lama. A progressive poet, spiritual teacher, and political leader, he is among the few figures to have wide recognition in both the convert and the immigrant Buddhist communities. He has had tremendous influence in this country first as an advocate for peace in Vietnam and later as a central figure in the emergence of Buddhist social activism, which will be dealt with in chapter 12.

Despite Nhat Hanh’s importance in this country, he is more the patriot in exile familiar from the anticolonial struggles of European history than an Americanizing Buddhist leader. Born in central Vietnam in 1926, he entered a Zen monastery in Hue at the age of seventeen, where he studied Zen and Pure Land Buddhism. He was fully ordained in 1949 and shortly thereafter began to take up a range of progressive causes in the monastic community in Saigon, formulating ideas that would later emerge as socially engaged Buddhism. In 1961, he made his first trip to the United States, during which he studied religion at Princeton and lectured on contemporary Buddhism at Columbia. He returned to Vietnam in 1964, shortly after the fall of Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime, and became deeply involved with the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam, a religious organization attempting to find peaceful solutions to the struggle between north and south. In 1965, he founded the Tiep Hien Order, the Order of Interbeing, an organization embracing laity, monks, and nuns that in subsequent years grew into an international movement.

In 1966, in an effort to encourage a peaceful resolution to the war, Thich Nhat Hanh began a nineteen-nation tour during which he met with numerous political and religious leaders. This tour prompted him to write Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire, a book that was significant in shaping the American public’s increasingly critical view of the war. Warned not to return to Vietnam due to the danger of assassination, Nhat Hanh went into permanent exile in France. In 1969, he formed the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation, a group that worked behind the scenes during the Paris Peace Talks, while also working and teaching at the Sorbonne.

After the fall of Saigon, Thich Nhat Hanh rededicated his monastic vocation to Vietnamese refugee work, the plight of political prisoners, and rebuilding relations between Vietnam and the West. In 1982, he established Plum Village, an international residential community dedicated to spiritual and social transformation, located on eighty acres of land in the Bordeaux region. Since that time, his influence in the United States has grown steadily. In the early 1980s, a number of western Buddhists began to be ordained in the Order of Interbeing. In 1983, the Community of Mindful Living, a Berkeley, California-based nonprofit organization, was formed to support the practice of mindfulness by conducting retreats, developing programs, and encouraging the establishment of residential retreat centers. There are now more than two hundred Communities of Mindful Living worldwide, the majority in the United States. Thich Nhat Hanh also pioneered mindfulness retreats as a way to address suffering caused by war, especially among Vietnam-era veterans still wrestling with the legacy of the conflict in southeast Asia.

Over the past three decades, Nhat Hanh has published sixty books that range from scholarship to poetry. These include The Miracle of Mindfulness, a wartime book he wrote for his students in Vietnam, and Being Peace, which introduced the principles of socially engaged Buddhism to western peace activists. More recently he published Living Buddha, Living Christ, a reflection on the ways of holiness and compassion as expressed in the two great contemplative religious traditions. The Mahayana principles informing Thich Nhat Hanh’s work are the interrelatedness of all living things and the nonjudgmental expression of universal compassion. One of his frequently cited poems, “Please Call Me By My True Names,” expresses these ideals powerfully and succinctly. It reads in part:

I am a member of the politburo, with

plenty of power in my hands,

I am the man who has to pay his

‘debt of blood’ to my people,

dying slowly in a forced labor camp.

My joy is like spring, so warm it makes

flowers bloom in all walks of life.

My pain is like a river of tears, so full it

fills up the four oceans.

Please call me by my true names,

so I can hear all my cries and my laughs

at once,

so I can see that my joy and pain are one.

Please call me by my true names,

so I can wake up,

and so the door of my heart can be left open,

the door of compassion.14

It is easy to say that the influx of Chinese, Koreans, and Vietnamese Buddhists into the United States over the past thirty years, whether as immigrants, refugees, or exiles, is contributing a great deal to American Buddhism. But, as is the case with Theravada immigrants, it is far more difficult to determine precisely what, in the long term, these contributions will turn out to be. The religious life of immigrant communities typically stabilizes in the third generation, after a pioneering generation has laid down traditional institutions, a second generation has rejected them, and a third begins to look back appreciatively to the accomplishments of their grandparents. By the end of the 1990s, it was clear that whatever Buddhism in this country is to become in the twenty-first century will be significantly shaped by the contributions of multicultural sanghas from China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Korea.