The presence in the United States of many forms of Buddhism has provided unprecedented opportunities for practitioners from a wide range of schools and traditions to engage in the creative exchange of ideas. Sometimes intra-Buddhist dialogue results in greater mutual understanding and cooperative ventures. But it also has led to the development of new and eclectic forms of philosophy and practice that are uniquely American. At the same time, interfaith dialogue has been proceeding among Buddhists, Christians, and Jews. These conversations are introducing elements of the dharma to people in America’s churches and synagogues and have inspired some Christians and Jews to draw selectively upon them as a source of religious renewal.

Intra-Buddhist Dialogue

One kind of intra-Buddhist dialogue occurs in regional or metropolitan associations formed by Buddhists, both immigrants and converts, from a variety of traditions and ethnic groups. These include organizations such as the Buddhist Association of Southwest Michigan, the Texas Buddhist Council, and the Buddhist Council of the Midwest that promote Buddhism through education, mediate local disputes, or organize celebrations of the Buddha’s birthday. Buddhists often come to a greater degree of understanding and respect for each other’s traditions as an indirect consequence of such practical efforts at local and regional cooperation.

In another, more formal kind of intra-Buddhist dialogue, representatives of different traditions meet in an effort to formulate doctrines and convictions to which they can collectively assent. The Buddhist Sangha Council of Southern California and the American Buddhist Congress were at the forefront of this kind of dialogue in the 1990s. Under their sponsorship, Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana Buddhists from a wide range of ethnic and national groups, both converts and immigrants, met at Hsi Lai Temple in 1997. Their goal was to articulate a vision of the “unity in diversity of Buddhism as a world religion” and to lay out “a set of principles which would reflect our common stand and mission.”1

In a document resulting from the meeting, representatives reviewed major steps in a process of intra-Buddhist dialogue that began in Asia in 1891, when Henry Steel Olcott, the American Theosophist, drafted a “Common Platform Upon Which All Buddhists Can Agree.” By gaining the approval of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhists from Sri Lanka, Burma, and Japan, Olcott helped to set in motion a pan-Asian Buddhist ecumenical movement. This movement was advanced in 1945 when Christmas Humphries, a Buddhist convert in Britain, drafted a similar document that was approved by the Supreme Patriarch of Buddhism in Thailand, prominent Buddhists in Sri Lanka, Burma, China, and Tibet, and leaders from a wide range of Japanese traditions. Subsequent meetings advancing this process were held in Sri Lanka in 1950 by the World Fellowship of Buddhists and at the Conference on World Buddhism in North America in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1987.

The Hsi Lai meeting established guidelines for intra-Buddhist consensus in the United States, while underscoring the importance of respecting communities’ differences. For instance, the delegates collectively recognized Gautama as the historical source of the dharma, an important point for Theravada Buddhists. But in keeping with the less historical perspective of the Mahayana tradition, they affirmed there have been in the past and will be in the future many other arhats, buddhas, and bodhisattvas. They acknowledged their common aspiration to attain liberation for themselves and for all beings, as well as their shared commitment to the Triple Gem, and they reaffirmed key doctrines such as karma and samsara, which many modern, particularly western, Buddhists have openly called into question. However, the representatives emphasized the continuing importance of “deferring to inter-traditional differences,” recognizing doctrinal, institutional, and ritual distinctiveness, as well as what they called the Buddha’s “guidelines for an open-minded and tolerant quest for Ultimate Truth.”2

More informal kinds of dialogue are ongoing at the grassroots level, particularly in convert communities, resulting in what Jack Kornfield has called “shared practice,” a process in which Zen leaders might investigate Theravada sutras or Insight meditation teachers study with Tibetan Buddhists.3 This kind of exchange has also fostered the emergence of what Don Morreale has called “non-sectarian” and “mixed tradition” Buddhism, innovative forms of the dharma that defy categorization in terms of Asian precedents.4 Such sharing and mixing of traditions suits many American centers, where Buddhists with long-term commitments to specific traditions often practice together in an ecumenical setting on a daily basis. It is also well suited to the fluidity that characterizes many Americans’ practice commitments. Quite often, converts spend years cultivating Zen, vipassana, or Tibetan meditation only to change their practice and their institutional affiliation. This eclectic and pragmatic approach comes naturally to Americans who, as a general rule, value personal religious experience highly but have little use for doctrinal consistency or patience with traditional orthodoxy.

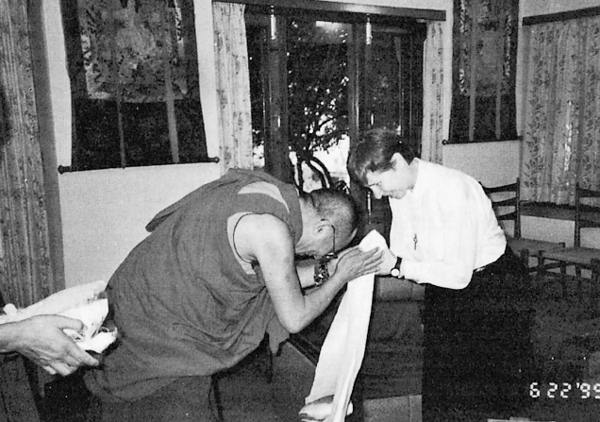

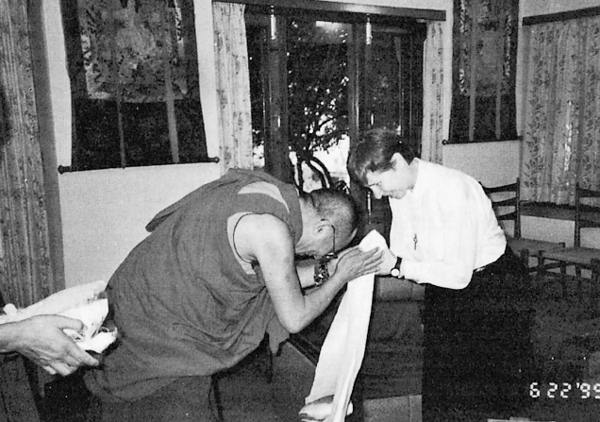

As the many traditions of Buddhism set down roots in the United States, religious dialogue is proceeding both among Buddhists and with those in other religions, particularly Christians and Jews. Here the Dalai Lama and Mary Margaret Funk, a Benedictine nun, express their mutual respect during a 1996 gathering at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, part of an extended dialogue between Buddhist and Christian monastics.

OUR LADY OF GRACE MONASTERY

Shared-practice and mixed-tradition Buddhism tends to be developed in an ad hoc fashion in response to particular communities’ needs or as converts begin to create new rites and ceremonies. In some cases, traditions are more formally integrated, such as in Shambhala International, where Tibetan Buddhism and Zen are combined as an expression of the diverse interests of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

A British teacher, Sangharakshita, the founder of Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO), has developed a nonsectarian form of the dharma on a more systematic basis. FWBO is among the most important Buddhist movements in the United Kingdom and Australia, but it also has centers in Europe and in the United States in Boston, Seattle, San Francisco, Montana, New Hampshire, and Maine. Sangharakshita founded the FWBO in 1967 after returning from a lengthy sojourn in Asia. His goal was to establish a new Buddhist path suited to the needs of western Buddhists, drawing inspiration from traditions across Asia. FWBO practice currently includes elements drawn from Zen and vipassana meditation, Tibetan-style visualizations, and physical disciplines such as yoga, ta’i chi, and massage therapy.

The creation of new forms of western Buddhism is a complex undertaking, and during the 1990s, Buddhist teachers held a number of consultations in an effort to develop a common understanding of the challenges they faced. In 1993, more than twenty Zen, Vajrayana, and vipassana teachers from America and Europe met with the Dalai Lama at his monastery in Dharamsala, India. Participants included Americans Thubten Chodron, Surya Das, Robert Thurman, and Jack Kornfield, and Britain’s Stephen and Martine Batchelor and Ajahn Amaro. During preliminary meetings, a number of issues emerged as central concerns, including the integration of the dharma with western psychology, gender equity, the future of monasticism in the West, the relationship between the dharma and Asian culture, and ethical norms for students and teachers.

In the course of the meetings, the Dalai Lama maintained his reputation for unimpeachable integrity and orthodoxy, which he balanced with a call for western teachers to proceed with the adaptation of Buddhism to the West. “The past is past,” Batchelor reported him saying on the last day. “What is important? The future. We are the creators. The future is in our hands. Even if we fail, no regrets—we have to make the effort.”5 Surya Das wrote that “One hour after the final meeting, while discussing the conference with two observers, His Holiness himself slapped his knee and exclaimed happily, ‘We have started a revolution.’”6

Western teachers took the opportunity to express their personal frustrations, including problems they had experienced with their own Asian teachers. For instance, one American Zen teacher recalled that after completing koan study and receiving dharma transmission and authority to teach, he remained unsatisfied and unhappy. He eventually parted company with his roshi, who could not tolerate his going into psychotherapy. Others raised questions about the ethics of Buddhist teachers. What was to be done about alcohol abuse, sexual harassment, egotism, and arrogance in teachers who claimed to be enlightened beings? Are realized teachers above ethical norms? How are legitimate limits to be established for American Buddhist communities, many of which came into being during the free-wheeling decades of the 1960s and ’70s?

Western teachers also explored the possibility of creating new Buddhist institutions. Some expressed the need for teacher training courses that amounted to more than years of sitting meditation under the direction of teachers. Others advocated the formation of a Sangha Council of Buddhist Elders to nurture monastics, redress inequities, and field questions about adapting the dharma to western lifestyles. There was consensus about the need for greater attention to the precepts, to ground Buddhist meditative practice in tradition-based morality and ethics to avoid the kind of scandals that erupted in the 1980s. According to Batchelor, the Dalai Lama had few concerns about whether or not westerners adapt Asian dharma names, wear clerical dress, or perform traditional ceremonies. He is also reported to have expressed a willingness to abandon Buddhist beliefs rooted in cosmological ideas that have been invalidated by scientific inquiry. He remained adamant, however, about the importance of observing the precepts and following the guidelines for monastic ordination as outlined in the vinaya.

Commentators recall the meeting as a transforming experience. One participant said it “had a bone-deep sense of rightness.”7 Another likened his encounter with the Dalai Lama to a Vajrayana empowerment, one that renewed his confidence in the mission to transmit the dharma to the West. Surya Das hit a visionary note often heard among Americans:

I myself felt that there was an incredible, instantaneous synergy which all the participants definitely experienced; a spontaneous energy now being felt all over the world, both within and beyond the Buddhist community—perhaps best summed up as an emerging American Buddhism, or a Western Buddhism, or perhaps even a New World Buddhism.8

Stephen Batchelor was more guarded and somewhat amused:

For the Americans, the Buddhist future unfolded as a kind of hi-tech Walden Pond peopled by dharma-intoxicated bodhisattvas. The disquieting features—institutions, sectarianism, scandal (the things we were here to talk about)—had conveniently evaporated. The Europeans were more cautious.9

Afterward, many western teachers signed an “Open Letter to the Buddhist Community,” in which they summed up lessons they took from the meeting. In the name of adapting the dharma, western Buddhists should freely draw upon the insights of other religious traditions and secular forms of thought and practice such as psychotherapy. To guard the integrity of the dharma, however, the student-teacher relationship must be understood to be one of mutual responsibility and respect. Teachers cannot stand above ethical norms; students must be encouraged to take care in selecting teachers. Sectarianism can be countered by dialogue, study, and shared practice, but teachers must learn to discern the difference between the dharma and its cultural expression. Their first priority is not to establish Buddhism per se in the West, but to cultivate a way of life in keeping with the essentials of the Buddha’s teachings.

Our first responsibility as Buddhists is to work towards creating a better world for all forms of life. The promotion of Buddhism as a religion is a secondary concern. Kindness and compassion, the furthering of peace and harmony, as well as tolerance and respect for other religions, should be the three guiding principles of our actions.10

Christians and Buddhists

The mood of the dialogue among Christians and Buddhists was captured in a review of Thich Nhat Hanh’s book Living Buddha, Living Christ in 1996 in Christian Century, a leading publication of American Protestantism. “A Zen Buddhist teacher sets a statue of Jesus on an altar alongside the Buddha and lights incense to both. A Catholic priest sits cross-legged in meditation and attends to his breathing as he has been instructed by Zen teachers.” The reviewer further observed that “Increasingly Buddhists and Christians are borrowing from each other’s traditions, and the results present new opportunities and new questions for both religions.”11

For many decades, Buddhist-Christian dialogue tended to focus on doctrinal and philosophical difficulties. Christians proclaim faith in God, while Buddhists are nontheistic. Christian theology is cast in terms of sin and redemption, while Buddhism teaches liberation from ignorance. Most Christian practice takes the form of prayer to a supreme being, while Buddhists who meditate do so to realize Buddha mind or Buddha nature. Christians consider Jesus a uniquely divine son of God, while Gautama was a mortal teacher. A great deal of effort has been devoted to exploring the consequences of these and other differences, a process of subtle theological and philosophical study and deep reflection by both Christians and Buddhists over the course of several generations.

During the past few decades, however, greater emphasis has been given to the new opportunities presented by interreligious dialogue. Many Christians have worked to move past problems in the dialogue process, but few are as well known as the late Thomas Merton, a Catholic monk and priest who played a key role in introducing Buddhism to American Christians. Born in France in 1915, Merton was the son of a New Zealander father and an American mother. Raised by them in a secular household, he underwent conversion in 1938 while studying in America, entered the Roman Catholic Church, and several years later joined the Trappist monastic community in Kentucky at the Abbey of Gethsemani. While in his early thirties, Merton wrote his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, which was published in 1948. It became a best-seller and helped to establish Merton as one of the most influential American writers on spiritual issues in the decades after the Second World War.

Over the next twenty years, Merton developed an unusually high public profile for a religious contemplative. While submitting to the rigorous monastic regime of Gethsemani, he also published on a wide range of topics from prayer and contemplation to literature and poetry. He strove to balance his life as a monk, hermit, and priest with his commitment to social justice, developing ideas about Christian responsibility as he reflected on nuclear arms, ecumenism, race issues, and the war in southeast Asia. When he died in Bangkok in 1968 at the age of fifty-three, Merton had a complex reputation as a public personality; a partner in dialogue with artists, poets, existential philosophers, and secular atheists; and a solitary mystic.

Merton was drawn to the religions of Asia in the late 1950s, but developed a particular interest in the similarities between Zen and Christian mysticism. He stood in a long line of Christian mystics who emphasized that God transcended all human concepts and language. They characterized knowledge of God as poverty of mind, a wilderness, the dissolution of self, and a state of unknowing, emphases Merton found echoed in the enigmatic wisdom of Zen koans and, above all, in the Mahayana idea of shunyata or emptiness. Merton’s interest in Zen led to a correspondence with D. T. Suzuki, the results of which were published in Merton’s Zen and the Birds of Appetite in 1968.

In that same year, Merton was granted permission by his abbot to make a journey to Bangkok, Thailand to participate in a meeting among Benedictines heading Catholic monasteries in Asia. But he took the opportunity to meet a range of Buddhist leaders such as Walpola Rahula, a leading authority on Theravada doctrine, Chogyam Trungpa, and Chatral Rinpoche, a highly respected lama in exile. Merton also journeyed to Dharamsala to meet with the Dalai Lama, with whom he established such cordial relations that their interview, during which they discussed their respective monastic traditions, was extended for three days.

Merton was not interested in conflating Buddhism and Christianity but in furthering conversations between practitioners of each faith, which led him to emphasize the importance of tradition. Speaking at the Spiritual Summit Conference sponsored by the Temple of Understanding, an international group of religious liberals, he made a passionate plea for Asian monks and nuns to maintain their traditions, even as they became more engaged with the western world and its complexities. Referring to the confusion that swept through the Catholic Church in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, Merton noted that “much that is of undying value is being thrown away irresponsibly, foolishly, in favor of things that are superficial and showy, that have no ultimate value.… I say as a brother from the West to Eastern monks, be a little careful. The time is coming when you may face the same situation and your fidelity to your ancient traditions will stand you in good stead. Do not be afraid of that fidelity.”12

Merton gave his last public address in Bangkok, a controversial one in which he explored the possibilities for dialogue between Christians and Marxists. Back in his room a short time later, he stepped from the shower, turned on a room fan with faulty wiring, and died by electrocution. His death occurred at about the time Buddhism was becoming a broadly popular religious movement in America, but his life and writing inspired numerous Christians to begin to explore Asian religions while remaining faithful to their own heritage.

In 1996, Merton’s memory was honored at an event that brought Christian and Buddhist monastics and lay practitioners together at the Abbey of Gethsemani. At the 1993 centennial of the World’s Parliament of Religions, the Dalai Lama had suggested a dialogue in a setting where he would be able to speak as a monk to other monastics. His suggestion was taken up by the Monastic Interreligious Dialogue, a Benedictine group established in 1978 to spearhead conversations between Christians and practitioners of Asian religions. Abbot Timothy Kelly and the monastic community in Kentucky quickly offered to host such an event, and in June 1996, more than 200 people gathered for “the Gethsemani Encounter.”

Participants included monks and nuns from thirty-nine Catholic monasteries worldwide; Tibetan, Zen, and Theravada monks, nuns, and teachers; heads of Catholic religious orders from Rome; and representatives of other Christian traditions. American Buddhists included Joseph Goldstein and Sharon Salzberg of IMS, Judith Simmer-Brown of the Naropa Institute, and Zoketsu Norman Fischer and Zenkai Blanche Hartman of the San Francisco Zen Center. Havanpola Ratanasara, Samu Sunim, and Yifa, a nun associated with Hsi Lai temple, were among the Asian teachers working in American Buddhist communities who attended. Prominent Christians included Margaret Mary Funk, a leading figure in the Christian “centering prayer” movement; David Steindl-Rast, a long-time Zen practitioner and senior member of the Benedictine Monastery of Mount Savior in New York; and Basil Pennington, a leading author on Christian mysticism serving at Our Lady of Joy Monastery in Hong Kong.

Participants delivered brief papers, but the heart of the meeting was personal and experiential rather than formal and academic. People engaged in sitting meditation on a daily basis, experienced each others’ religious rituals, and explored what was distinct to each particular tradition and what they shared. They discussed the relation between contemplation and social action and the significance of Christ and Buddha in a cross-traditional frame of reference. In the course of the proceedings, Maha Ghosananda, a Cambodian monk and peace activist, led a spontaneous walking meditation to Merton’s grave. Pierre François de Béthune, a Belgian Benedictine, later wrote that the Gethsemani Encounter marked “a new climate of openness” and a “profound change in thinking.” Buddhists and Christians could now see themselves together “as forerunners of a spiritual unity that is prophetic of all humankind.”13

Many Buddhists have also been working independently to further the conversation between the two traditions. Zen Master Soeng Hyang (Barbara Rhodes) and other senior teachers are engaged in various facets of Buddhist-Christian dialogue led by the Kwan Um School of Zen. Ruben Habito, a dharma heir of Yasutani Koun Roshi and student of Yasutani Roshi before his death, leads the Maria Kannon Zen Center in Dallas, formed in 1991 as a place for people of various faiths to practice Zen. Like most others engaged in Buddhist-Christian dialogue, Habito sees no conflict between Christian faith and Buddhist practice, and in a 1997 interview addressed what for many Christians remains an important question. “I would like to assure everyone concerned that Zen does not threaten a healthy faith in the ultimate as expressed in the Christian tradition,” Habito noted. Zen is “an invitation to a direct experience, and the only thing that is required is a willingness to engage in that journey of self-discovery.” Whether one is Christian, Jew, or Muslim, Zen can “affect their own faith understanding creatively or positively.”14

Robert E. Kennedy, a Jesuit priest, a professor of theology, a Japanese language instructor, and a psychotherapist with a private practice, began to study in Japan in the mid-1970s but received dharma transmission from Bernard Glassman in 1991, becoming one of the first American Catholic priests authorized to teach Zen. In his book Zen Spirit, Christian Spirit: The Place of Zen in Christian Life, Kennedy demonstrates how Buddhist and Christian scripture, practice, and concepts illuminate each other, while remaining distinct. But by way of introduction, he makes it clear that “I never have thought of myself as anything but Catholic and I certainly have never thought of myself as a Buddhist.… What I looked for in Zen was not a new faith, but a new way of being Catholic that grew out of my own lived experience.” Recalling his first teacher, Kennedy writes:

Yamada Roshi told me several times he did not want to make me a Buddhist but rather he wanted to empty me in imitation of “Christ your Lord” who emptied himself, poured himself out, and clung to nothing. Whenever Yamada Roshi instructed me in this way, I thought that this Buddhist might make a Christian of me yet.15

Jews, Buddhists, and Jewish Buddhists

The dialogue between Jews and Buddhists has taken on its own distinct character, due in part to the important role played by Jewish Buddhists in the introduction and adaptation of the Buddha’s teachings to America. American Jews have a long history of exploring the dharma. Charles Strauss, among the earliest American Buddhists, took refuge following the World’s Parliament of 1893. Allen Ginsberg, one of the most passionate and powerful voices of the Beat generation, drew much of the force for his poetry from being both Buddhist and Jewish. But other issues have also strengthened this connection, including the similarities and differences between traditional Jewish mysticism and Tibetan Buddhism and the experience shared by Jews and Tibetans of living in diaspora communities.

The publication of Rodger Kamenetz’s The Jew in the Lotus: A Poet’s Rediscovery of Jewish Identity in Buddhist India in 1994 drew attention to the growth of the Jewish-Buddhist dialogue movement. Kamenetz explored the phenomenon of Jewish Buddhists, which many people had noted but few had directly addressed. He cited surveys that indicated the proportion of Jews in Buddhist groups was up to twelve times that of Jews in the population of the United States. Moreover, many Jews held prominent positions in American Buddhist communities. Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, Jacqueline Schwartz, and Sharon Salzberg co-founded the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts. Sam Bercholz, founder of Shambhala Publications, and Rick Fields, a chronicler of American Buddhism, both studied under Chogyam Trungpa at the Naropa Institute. Bernard Glassman of the Zen Peacemaker Order and Norman Fischer of the San Francisco Zen Center are two of a number of leaders from Jewish backgrounds in the Zen community. Kamenetz also popularized the term Jubu, which since the 1960s had gained a degree of currency among Jews in American Buddhism communities.

In The Jew in the Lotus, Kamenetz also familiarized general readers with a process of exchange between Jews and Buddhists that had been set in motion at the instigation of the Dalai Lama. During the 1980s, the American Jewish World Service gave assistance to Tibetan exiles in south Asia. Grateful for aid and aware that many Buddhists in America came from Jewish backgrounds, the Dalai Lama told agency leaders of his desire to learn more about Jews and Judaism. This request eventually led to a meeting between Jewish rabbis and scholars and the Dalai Lama in the course of his 1989 America tour, which in turn led to a more ambitious meeting in Dharamsala in 1990, recorded in Kamenetz’s illuminating and engaging book.

The delegates to Dharamsala represented a wide range of positions in Judaism, but tended to be liberals in their respective communities. Among them was Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, a charismatic rabbi known for his upbeat interpretation of Kabbalistic mysticism, and Irving and Blu Greenberg, a couple well known as representing the progressive wing of Orthodoxy. Also present were Reform Rabbi Joy Levitt, Jonathan Omer-Man, founder and president of a Jewish religious center in Los Angeles, and Moshe Waldoks, a spiritual renewal leader well known for his Big Book of Jewish Humor. Nathan Katz represented Jewish scholars in Buddhist Studies and Paul Mendes-Flohr, secular academics in Jewish Studies. A portion of The Jew in the Lotus is devoted to their debates about the religious protocol appropriate to their meeting with the Dalai Lama, which makes the book an intimate introduction to religious sensibilities in contemporary Judaism.

Kamenetz focuses much of his account on a comparison of Jewish mysticism and Tibetan Buddhism. The discussion of mysticism arose one afternoon when Schachter, who had come to Dharamsala with charts outlining the similarities and differences between Kabbalistic and tantric mysticism, fell into a one-on-one conversation with the Dalai Lama, who became fascinated by the way Kabbalists correlate levels of creation with the Hebrew alphabet and emotional states. He soon was asking Schachter probing questions about angels in the Kabbalah and how they compared to Tibetan dharma protectors and bodhisattvas. Their conversation then turned to a comparison of what Kabbalists term ain sof and Mahayana Buddhists call shunyata, both of which convey ideas about the boundless quality of ultimate reality.

The Dalai Lama then initiated a discussion about strategies used by Jews to keep their tradition alive in the two thousand years of the diaspora. Levitt spoke of how the synagogue became a community and cultural center, a place of prayer and learning, and a source of communal values. Blu Greenberg talked about how the family was the center of Jewish religious life for many centuries. Kamenetz reports that this was new information to the Dalai Lama who, despite the fact that he was the leader of the Tibetan people, was most familiar with life among celibate clergy. He also tended to view religion as distinct from culture, so he found it of particular interest that one could be both secular and Jewish. Waldoks and others were frank in expressing their pain at losing Jews to Buddhism, so the Dalai Lama’s views on conversion were met with general approval. “In my public teaching I always tell people who are interested that changing religions is not an easy task. So therefore it’s better not to change, better to follow one’s own traditional religion, since basically the same message, the same potential is there.”16

The Dalai Lama also offered the delegates insights he had gained as the leader of a society thrust into the modern world almost overnight. He urged Jews to revive mystical teachings that, much like tantra, had been kept in secrecy for many centuries. He had also learned that there was nothing to be gained by attempting to limit people’s right to choose. Tibetans were also exploring other traditions and he found it best to be prepared to find something of value in every religion. Finally, he had learned to be realistic about the challenges to tradition posed by modernity. “If we try to isolate ourselves from modernity, this is self-destruction,” he noted. “You have to face reality. If you have reason, sufficient reason to practice a religion, sufficient value in that religion, there is no need to fear. If you have no sufficient reason, no value—then there’s no reason to hold on to it. Really. I feel that.”

So you see, the time is changing. Nobody can stop it. Whether God created it—or nature is behind it, nobody knows. It is a fact. It is reality. So we have to follow the time, and live according to reality. What we need, ourselves, as religious leaders, is to do more research, find more practices to make tradition something more beneficial in today’s life.17

Several years later, Kamenetz was instrumental in starting another Jewish-Buddhist collaboration called Seders for Tibet. Seder, the Passover meal commemorating the ancient Hebrews’ release from slavery in Egypt, has been important in maintaining Jewish intergenerational memory and collective identity. The idea to recast the ritual to include the plight of Tibet in exile came to Kamenetz in 1996 upon his return from another trip to Dharamsala, when he sought to find a way to foster Jewish-Tibetan solidarity. Sponsorship of Seders for Tibet was soon taken up by The International Campaign for Tibet, leaders in different Jewish denominations, and Jewish students on campus. In a surprise move, the Dalai Lama expressed his desire to attend a seder during a visit to Washington, D.C. in 1997.

As he recalls in Stalking Elijah: Adventures With Today’s Jewish Mystical Masters, Kamenetz found himself in April of that year gathered with Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys, and the Dalai Lama at a seder hosted by Rabbi David Saperstein of Washington’s Religious Action Center. “At one point,” he writes, “the fifty of us crowded in a small room grew silent as we listened to a recording smuggled out of Tibet.”

We heard the quavering voice of Phuntsok Nyidron, a nineteen-year-old nun serving seventeen years in Drapchi prison. From far away, she sang to our seder about the meaning of freedom. Together we read the translation of her lyric, “We the captured friends in spirit … no matter how hard we are beaten/Our linked arms cannot be separated.”18

At the closing of the seder, they recited the traditional Passover prayer of hope—“L’Shana Haba-ah B’Yerushalayim, next year in Jerusalem”—but added, “L’Shana Haba-ah B’Lhasa. Next year in Lhasa.”19

The Dharamsala meeting in 1990 and Seders for Tibet in 1997 are only two landmarks in a broader process of dialogue among Jews and Buddhists. Tikkun, a progressive journal of contemporary Judaism, noted in 1998 that “for more than a generation Jewish seekers have hit the enlightenment road and have traveled every path. Now we are hitting middle age and are producing a literature, a Jewish literature, describing our peregrinations.… Of particular interest is the eruption of new material dealing with Judaism and Eastern religions.” Among the books cited were Kamenetz’s The Jew in the Lotus, Norman Fischer’s Jerusalem Moonlight, Judith Linzer’s Torah and Dharma: Jewish Seekers in Eastern Religions, and Sylvia Boorstein’s That’s Funny, You Don’t Look Buddhist: On Being a Faithful Jew and a Passionate Buddhist.

Boorstein’s book is an intimate and accessible account of her successful attempt to reconcile a dual religious identity. She was raised in Brooklyn, New York, but eventually drifted away from a strong sense of Jewish religious identity. After earning a Master’s of Social Work at the University of California and a Ph.D. in psychology from the Saybrook Institute, she practiced as a psychotherapist. In the mid-1970s, she took up vipassana meditation and later became a teacher at Insight Meditation Society. In the 1980s, she was among the Buddhist representatives at a major Buddhist-Christian dialogue hosted by the Naropa Institute. By about the mid-1990s, however, she also began to describe herself as an observant and prayerful Jew.

In That’s Funny, You Don’t Look Buddhist, Boorstein recalls the discomfort she once experienced trying to be both Jewish and Buddhist. When teaching Jews meditation, she feared but did not experience disapproval. Among Buddhists, she was reluctant to identify herself as Jewish. The issue came to a head at the meeting of western Buddhist teachers with the Dalai Lama in 1993, after a question was asked in a preliminary meeting: What is the greatest current spiritual challenge in your practice and teaching? Boorstein recalls thinking to herself, “‘Okay, this is it! These are major teachers in all lineages, these are people I respect and who I hope will respect me.’ And I said my truth”:

I am a Jew. These days I spend a lot of my time teaching Buddhist meditation to Jews. It gives me special pleasure to teach Jews, and sometimes special problems. I feel it’s my calling, though, something I’m supposed to do. And I’m worried that someone here will think I’m doing something wrong. Someone will say, “You’re not a real Buddhist.”

Posing the question in an atmosphere charged with such creative potential, however, provided the solution. “I never did ask the Dalai Lama if what I am doing is okay,” she later wrote. “It had become, for me, a nonquestion by the time we got to our meeting.”20

As Boorstein describes it, she came to understand that she is a Jew because her parents provided her with a loving upbringing and being Jewish is a fundamental part of her personal identity. Yet she became a religious Jew once again because of her experience with Buddhism. From the first day of her first Buddhist retreat, she recalls being captivated by the Buddha’s teaching on the cessation of suffering, which gave her a way to pursue a life devoted to cultivating compassion and contentment. This happiness with herself, in turn, led her back to Judaism. “I am a prayerful Jew because I am a Buddhist,” she wrote. “As the meditation practice that I learned from my Buddhist teachers made me less fearful and allowed me to fall in love with life, I discovered the prayer language of ‘thank you’ that I knew from my childhood returned, spontaneously and to my great delight.”21

Boorstein devotes much of her book to teasing out parallels between the traditions of Judaism and Buddhism. She identifies the V’ahavta prayer in Judaism—“And you shall love the Lord Your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength”—as Judaism’s form of metta, or lovingkindness, practice. She sees Abraham’s saying “Hineyni” or “Here I am” to God in the Book of Genesis as an expression of the mindfulness Buddhists cultivate in meditation. The author of the Book of Job who spoke of the Voice from the Whirlwind was alluding to an experience of God she understands in terms of emptiness. Boorstein conveys how she has come to think religiously on a number of levels when she discusses her understanding of Buddhist ideas about karma and the interdependence of all beings.

To myself, I say, “God reigns, God reigned. God will reign forever.”

To my grandchildren, I say, “Everything, no matter what, is okay. And we’ll try as hard as we can to fix anything that is broken.”

To Buddhist students, I say: “The cosmos is lawful. Karma is true. Everything evolves from a single interconnected source. Nothing is disconnected from anything else. Future events are dependent on our actions now. Virtue is mandated; we are responsible for one another. Everything matters.”22

Intra- and interreligious dialogue is a complex, multifaceted undertaking with great philosophical and theological implications that lie beyond the scope of this book. But these selected developments suggest how the dharma is being reshaped in new and challenging ways as it sets down roots in this country. There are both problems and creative possibilities in this process. On one hand, many view religious traditions as having developed internal consistency over centuries, with scripture, doctrine, and ritual practices working together to shape a path that enables practitioners and communities to cultivate both spirituality and personal and collective identities. On the other hand, all living traditions are more or less in a constant state of change, even if only very cautious, and the movement of the dharma to America will require significant adaptations and innovations.

Buddhism in America is in a state of creative ferment, in which the forces of tradition and innovation are at work both within and among a wide range of religious traditions. The fundamental teachings of the Buddha, which are themselves subject to a variety of traditional interpretations, have been introduced into a new cultural environment, setting in motion processes of revitalization and re-creation. Scholars routinely use a kind of shorthand to describe comparable processes that took place in Buddhist Asia. Ancient Theravada Buddhism absorbed the animistic traditions of rural Sri Lanka, for instance, and Indian Tantric Buddhism fused with the shamanic religion of central Asia. In the United States there is as yet no comparable shorthand; however, it is clear that intra-Buddhist dialogue and interreligious dialogue among Buddhists, Christians, and Jews is helping to develop distinct forms of Buddhism that reflect the uniqueness of a new, North American setting.

Thus it is no surprise that some leaders of particular traditions, schools, and lineages stand guard over boundaries that give them their coherence and consistency. Some may dismiss this as sectarian rivalry, as no doubt it sometimes is, but the instinct to defend tradition can be healthy and deserves to be encouraged. On the other hand, there is no question that the United States presents a perhaps unprecedented opportunity for creative interaction. Cross-fertilization among different traditions is occurring in many different quarters and in a wide variety of ways. That some of this will, in the long term, help to shape uniquely American forms of the dharma can be considered inevitable.