CHAPTER 3

MANAGING MISSION, STRATEGY, AND FINANCIAL LEADERSHIP

- 3.1 VALUE OF STRATEGIC PLANNING

- 3.2 WHAT IS STRATEGIC PLANNING?

- 3.3 WHAT ARE THE ORGANIZATION’S MISSION, VISION, AND GOALS/OBJECTIVES?

- 3.4 STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT PROCESS

- 3.5 IMPLEMENTING THE STRATEGIC PLAN

- 3.6 PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

- 3.7 STRATEGIC PLANNING PRACTICES: WHAT DOES THE EVIDENCE SHOW?

- 3.8 CONCLUSION

Thirty years ago a nonprofit financial management guide would have scarcely mentioned strategy or strategic management. In their expanded roles as strategic business partners, however, financial managers and board finance committees are increasingly involved in strategy development, evaluation, and implementation. According to the Association for Financial Professionals' 2016 benchmark survey of high-level corporate finance professionals regarding financial planning and analysis (FP&A):

FP&A is becoming a forward-looking operation. What began as a function that reported merely on past events is now transforming into one that focuses on why those events occurred as well as what is likely to happen next. FP&A is working hand in hand with business units to create realistic business plans. Consequently, it must stay tuned in to the organization's overall strategic objectives, assess risks and identify growth opportunities. FP&A is evolving into the analytics hub at an increasing number of companies – becoming the “brains” of the organization.1

This ongoing development requires that financial professionals are in fact an integral part of planning and strategy development, regardless of the sector in which they work.

This chapter first develops an understanding of mission, vision, and strategy. It then profiles a major shortcoming of management practices: failure to implement strategic decisions properly. Using information from some of the best available sources, the chapter next provides an overview of strategic planning. The last part of the chapter presents some of the performance management systems that may be used to diagnose current strategies and how well they are being executed by the organization. The balanced scorecard, which is being used by more organizations each year, is prominent within these performance management systems. However, several portfolio models are also available to use, and both types of models offer great promise to financial managers and boards wishing to make better strategic decisions and better meet the mission, vision, and goals of their organizations. We also advocate the use of dashboard reports to monitor the achievement of key metrics. Finally, this chapter places financial leadership in a more prominent place in strategic planning.

3.1 VALUE OF STRATEGIC PLANNING

Before delving into the specifics of strategic planning, let us consider some motives for engaging in planning. The process of strategic planning and evaluation is as important, or more important, than the plan itself. Expect your organization to glean these benefits from the planning process. Successful strategic planning:

- Leads to action

- Builds a shared vision that is values-based

- Is an inclusive, participatory process in which board and staff take on a shared ownership

- Accepts accountability to the community

- Is externally focused and sensitive to the organization's environment

- Is based on quality data

- Requires an openness to questioning the status quo

- Is a key part of effective management2

Regrettably, while almost all nonprofits say that they are involved in strategic planning when asked, too often the planning that is practiced is mired in the budgeting process. This is not strategic thinking; it is merely bean counting. To plan successfully, an organization must have a strategic thinker at its helm and an environment that infuses strategic thinking into all of its endeavors. Regardless of line and staff relations, everyone from the executive director down must adopt a planning philosophy. Planning is not merely an extension of the budgeting process; good planning identifies the key issues to which the appropriate numbers can later be attached.

Being strategic, rather than simply devising a strategic plan, is the key to effectively reaching the organization's mission. We concur with the findings of the “Strategy Counts” initiative conducted by the Kresge Foundation, and this chapter is framed in the following context:3

An early observation suggests that there is no lack of compelling vision or of worthy aspirations by nonprofits. More often, the challenge is in the effective deployment of strategy…While multiyear strategic plans remain useful, the value diminishes if organizations take an episodic approach to strategy. Instead, strategy leaders, from the [20] pilot sites and beyond, are taking a more continual approach to strategy in which the strategy is aligned with and guides daily operations.

In your role as strategic business consultant and financial educator, we encourage you to see yourself as an essential part of the team that aligns strategy and ensures that the strategy is implemented.

3.2 WHAT IS STRATEGIC PLANNING?

“Strategic Planning is a systematic process through which an organization agrees on and builds key stakeholder commitment to priorities that are essential to its mission and responsive to the organizational environment. Strategic planning guides the acquisition and allocation of resources to achieve these priorities.”4

Strategic planning involves deciding how to combine and employ resources. It is not a one-time exercise but rather an ongoing process and finance managers play a prominent role. The numerous objectives and customers in the strategic decision-making environment of a nonprofit often disorient business professionals who join nonprofit boards.

Why do nonprofit organizations present unique managerial problems? Six complex factors affect decision making in nonprofit organizations:

- Intangibility of services

- Weak customer influence

- Strong professional rather than organizational commitment by employees

- Management intrusion by resource contributors

- Restraints on the use of rewards and punishments

- The influence of a charismatic leader and/or organizational mystique on choices5

Nonprofit decision-making complexity certainly contributes to the primary cause of failure in at least one-half of strategic decisions: poor decision-making processes.6 Together these six influences weaken decision making and augur inefficiency and ineffectiveness for the nonprofit. Financial managers and finance-oriented board members may improve decision making by ensuring that, at a minimum, financial aspects of decisions are included and properly appraised. Less obvious is the tendency for some nonprofits to lose their program focus and overemphasize revenue generation: The joint effect of (1) constantly needing to seek resources, (2) not having a profit motive, and (3) not being able to accurately measure service quality is to make nonprofit organization managers concentrate more on fundraising than on the needs of service users.7 It is a struggle that the typical organization with too little liquidity will constantly have to grapple with. That tendency is compounded when the vision and mission of the organization are unclear, unfocused, or forgotten.

3.3 WHAT ARE THE ORGANIZATION'S MISSION, VISION, AND GOALS/OBJECTIVES?

We will use these definitions of mission, vision, and goals/objectives:8

- Mission communicates purpose (why the organization exists, the end result the organization is striving to accomplish), the “business” the organization is in as it tries to achieve its purpose, and possibly a statement of guiding values or beliefs; this is captured in the “mission statement.”

- Vision is a mental image of what successful attainment of the mission would look like or how the world would be different if and when the organization's mission is accomplished.

- Goals/Objectives are either (1) program goals/objectives – program-by-program statements of the organization's plan of action, telling what it intends to do over a several-year period; or (2) management goals/objectives – organization development plan of action for each function or area within the organization for which there is a strategic initiative being implemented.

An organization's mission statement should clearly communicate what it is that it does. Many mission statements succumb to an overuse of words in general, but especially of jargon. Good mission statements should be clear, memorable, and concise. Some examples of concise mission statements are:9

- TED: Spreading ideas.

- The Humane Society: Celebrating animals, confronting cruelty.

- Smithsonian: The increase and diffusion of knowledge.

- Wounded Warrior Project: To honor and empower wounded warriors.

- Public Broadcasting System (PBS): To create content that educates, informs and inspires.

- USO: Lifts the spirits of America's troops and their families.

Vision statement (Desired End-State): A one-sentence statement describing the clear and inspirational long-term desired change resulting from an organization or program's work. Some examples are:

- Oxfam: A just world without poverty.

- Feeding America: A hunger-free America.

- Human Rights Campaign: Equality for everyone.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society: A World Free of MS.

- Alzheimer's Association: Our vision is a world without Alzheimer's.

- Habitat for Humanity: A world where everyone has a decent place to live.10

Peter Drucker indicates that there are three “musts” when you develop your organization's mission; consider whether your organization has incorporated these items into its mission development:

- Study your organization's strengths and its past performance. The idea is to do better those things you already do well – if those are the right things to do. The belief that your organization can do everything is just plain wrong. When you violate your organization's values, you are likely to do a poor job.

- Look outside at the opportunities and needs. With the limited resources you have (including people, money, and competence), where can you really make a difference? Once you know, create a high level of performance in that arena.

- Determine what your organization really believes in. Drucker notes that he has never seen anything being done well unless people were committed. One reason why the Edsel failed was that nobody at Ford believed in it.11

We will cover some specifics of strengths-weaknesses-opportunities-threats (SWOT) analysis later in the chapter. In implementing your organization's mission, you should ask several questions when viewing possible activities and programs to get involved with. Determine what the opportunities and needs are. Then ask if they fit your organization. Are you likely to do a good job at meeting them? Is there organizational competence in these areas? Do the opportunities and needs match the organization's strengths? Do the board, the staff, and the volunteer contingent really believe in this?

(a) STRATEGY AND THE “BOTTOM LINE”. Historically, nonprofit organizations have not considered themselves to have a “bottom line.” They seem to consider everything they do to be righteous and to serve a cause, and so they are not willing to insist that if a program does not produce results, then perhaps resources should be redirected. Nonprofits need the discipline of organized abandonment and the critical choices that are involved. Organized abandonment involves a carefully planned reevaluation of programs and activities, with a pruning process applied to certain of those programs in order to free up resources for reapplication. Later in the chapter we provide a tool to guide these organized abandonment decisions.

In addition to overall strategic direction, functional, area-specific strategies are necessary. In his studies of nonprofit organizations, Drucker noted a critical missing ingredient: the lack of a fund development strategy. He notes that the source of money is probably the greatest single difference between the nonprofit sector and business and government. The nonprofit institution has to raise money from donors. It raises its money – at least, a large portion of it – from people who want to participate in the cause but who are not beneficiaries or clients. Money is scarce in nonprofits. In fact, many nonprofit managers seem to believe that their difficulties would be solved if only they had more money. Drucker mentions that some of them come close to believing that raising money is really their mission! As an example, he cites the presidents of private colleges and universities who are so totally preoccupied with raising money that they have neither the time nor the thought for leading their organizations. What happens then? In his words:

But a nonprofit institution that becomes a prisoner of money-raising is in serious trouble and in a serious identity crisis. The purpose of a strategy for raising money is precisely to enable the nonprofit institution to carry out its mission without subordinating that mission to fund-raising. This is why nonprofit people have now changed the term they use from “fund-raising” to “fund development.” Fund-raising is going around with a begging bowl, asking for money because the need is so great. Fund development is creating a constituency which supports the organization because it deserves it. It means developing what I call a membership that participates through giving.12

Innovative organizations, both businesses and nonprofits, generally look outside and inside for ideas about new opportunities. A primary example, cited by Drucker, is the megachurch. The pastoral megachurch looks at changes in demographics, at all the young, professional, educated people who have been cut off from their roots and need a community, assistance, encouragement, and spiritual strength. The change seen outside is an opportunity for organizations that are observant. Look within the organization and identify the most important clue pointing the way to strategic venturing: Generally, it will be the unexpected success. Most organizations feel that they somehow deserve the unforeseen major successes and engage in self-congratulation. What they should be doing is seeing a call to greater outreach and action. As an example, Drucker references how The Girl Scout Association discovered that the social phenomenon of “latchkey kids” became a tremendous opportunity, which spawned the Daisy Scouts.

When doing anything new, do not leap directly from “idea stage” to “fully operational stage.” Test the idea, possibly with a limited rollout (often called the pilot stage). A great idea can be labeled a failure when tiny and easily correctable flaws destroy the confidence of your clients, volunteers, or employees.

As a final note, Drucker has noted how persistence can breed improved performance and yet sometimes the best thing to do is cut your losses:

When a strategy or an action doesn't seem to be working, the rule is, “If at first you don't succeed, try once more. Then do something else.” The first time around, a new strategy very often doesn't work. Then one must sit down and ask what has been learned. “Maybe we pushed too hard when we had success. Or we thought we had won and slackened our efforts.” Or maybe the service isn't quite right. Try to improve it, to change it and make another major effort. Maybe, though I am reluctant to encourage that, you should make a third effort. After that, go to work where the results are. There is only so much time and so many resources, and there is so much work to be done.13

(b) WHAT ARE STRATEGIC DECISIONS? Examples of strategic decisions are:

- Deciding to offer a new product line or service

- Deciding to serve a new clientele

- Deciding to deliver services abroad for the first time

- Deciding to affiliate with another organization

Whenever organizations significantly alter their activities, the strategic management process is at work.

Three factors distinguish strategic decisions:

- Strategic decisions deal with concerns that are essential to the livelihood and survival of the entire organization and usually involve a major portion of the organization's resources.

- Strategic decisions involve new initiatives or areas of concern and usually address issues that are unusual for the organization rather than issues that are easily handled with routine decision making.

- Strategic decisions could have major implications for the way other, lower-level decisions in the organization are made.

Henry Mintzberg, one of the great management thinkers of our day, views strategy as a pattern in a stream of decisions.14 There are two ramifications for the organization:

- Strategy is not one decision but must be viewed in the context of a number of decisions and the consistency among them.

- The organization must be constantly aware of decision alternatives.

Think about strategy as the reasoning that guides the organization's choices among its alternatives.

Is an organization's strategy always the result of a planned, conscious effort toward goals that results in a pattern, termed a deliberate strategy? Not at all. Many times, emergent strategy emerges from the bottom levels of the organization as a result of its activities. Or it may come out of the implementation process – in which changes in goals and “reorienting” may produce strategies that are quite different from what the organization originally intended. As a starting point in diagnosing an organization, study the decisions themselves and infer strategy from the strategic decisions.

3.4 STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT PROCESS

Strategic management refers to the entire scope of strategic decision making in an organization; as it can be defined as the “set of managerial decisions that relates the organization to its environment, guides internal activities, and determines the long-term performance of the organization.”15

There are three steps in the strategic management process; thus far in this chapter, the first step has been our focus:16

- Step 1. Strategy formulation. The set of decisions that determine the organization's mission and establishes its goals/objectives, strategies, and policies

- Step 2. Strategy implementation. Decisions that are made to put a new strategy in place or to reinforce an existing strategy; includes motivating people, arranging the right structure and systems (see Chapter 4), establishing cross-functional teams, establishing policies, and maintaining the right organizational culture to make the strategy work

- Step 3. Evaluation and control. Activities and decisions that keep the process on track; include following up on goal accomplishment and feeding back the results to decision makers.

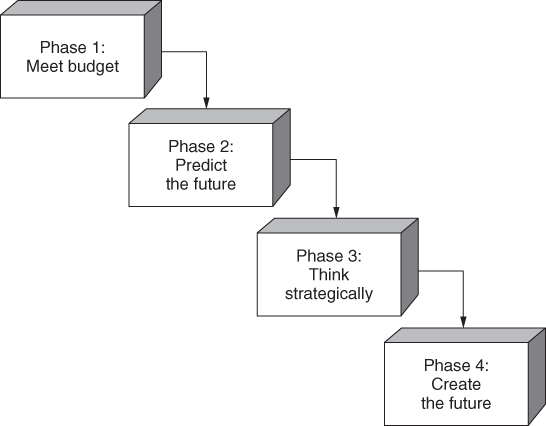

In their studies of organizational development, Stahl and Grigsby have noted regularities that help us understand the progression of strategic management. The organization will likely have to go through the phases, with each one showing increasing effectiveness, shown in Exhibit 3.1.

Source: Adapted and reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. From “Strategic Management for Competitive Advantage,” by Frederick Gluck, Stephen Kaufman, and A. Steven Walleck, July–Aug. #58 1980 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

Exhibit 3.1 Strategic Management Phases

- Phase 1: Basic Financial Planning: Meet Budget

- Controlling operations

- Setting annual budget

- Focusing on the various functional areas (such as development) in the organization

- Phase 2: Forecast-Based Planning: Predict the Future

- Improved planning for growth

- Environmental analysis

- Multiyear forecasts

- Static resource allocation

- Phase 3: Externally Oriented Planning: Think Strategically

- More responsive to markets and competition

- Better analysis of situations and assessment of competition

- Evaluate strategic alternatives

- Dynamic resource allocation

- Phase 4: Strategic Management: Create the Future

- Create competitive advantage using all resources as a group

- Strategically select planning framework

- Planning process is creative and flexible

- Value system and culture support planning and plans

You may immediately apply this framework to your organization in two ways:

- In which phase do you find your organization? Based on where your organization is, how will this help or hinder strategic decision making?

- What step(s) might you take to help move your organization and its leadership to the next phase?

(a) SWOT ANALYSIS. When formulating your organization's strategic plan, the board and management team must analyze conditions inside the organization as well as conditions in the external environment. This analysis is now so conventional in strategic management that it is referred to as analysis of internal strengths and weaknesses and external opportunities and threats (or challenges) – in a word, SWOT. Exhibit 3.2 provides the worksheet that includes all components of SWOT analysis. You may wish to duplicate it and use it to diagnose your organization's present situation.

Exhibit 3.2 Worksheet for Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, and Threat (SWOT) Analysis

(b) WHAT ARE INTERNAL STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES? Issues that are within the organization and usually under your management's control are internal strengths and weaknesses. A strength is anything internal to the organization that may lead to an advantage relative to your funding or service competitors and a benefit relative to your clients. A weakness is anything internal that may lead to a disadvantage relative to those competitors and clients. These internal items may have been inherited from past management teams or were operational in the past but are currently less relevant.

A talented and experienced top management team is a great internal asset, especially when the organization is in a rapidly changing or very competitive environment. If your board brings a fresh and questioning perspective to strategic issues, instead of rubber-stamping management's ideas, as so many boards do, count your board as an internal strength.

Financial management is an area in which possessing strength can advance most decisions management might implement. But a weak financial position (usually signaled by very low levels of liquidity and/or very high levels of debt) severely hampers the organization. A weak financial position can prevent an organization from responding to even the most attractive, mission-enhancing external opportunities.17 Weaknesses often give rise to functional (management) strategies.

(c) USING ENVIRONMENTAL SCANNING TO DETECT EXTERNAL OPPORTUNITIES AND THREATS. External opportunities and threats (or challenges) are social, economic, technological, and political/regulatory trends and developments that have implications for your services, your clients, your donors, or other key parts of your organization.

Your organization should be continually engaging in environmental scanning to recognize these trends and developments and how they will affect revenues and expenses as well as risks. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, meant a significant decline in donations for many organizations, as monies were donor-directed to the rescue effort and organizations like the American Red Cross. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 and, to a lesser extent, hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria in 2017 had much the same effect, with the Salvation Army, World Vision, and the American Red Cross seeing revenues and expenses shift upward, while many organizations experienced donation declines. The “Great Recession” that began in late 2007 had a negative effect on many nonprofits, especially those human services organizations whose donations and grants did not keep pace with exploding demand for their services. Organizations holding larger liquidity were very glad they had built up their liquidity positions above those levels of most organizations and above the commonly given advice of only three months of operating expenses. (Refer to Chapter 2 for reasons to hold larger cash reserves and operating reserves and Chapter 14 on development of risk reserves.)

(d) STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT IS AN ONGOING PROCESS. Strategic management is a process, not just a one-time product of some long meetings. It is more of a management philosophy than a simple methodology. Yesterday's ideal plan will sometimes become substandard due to some changed or just-discovered internal factor (a strength or weakness, possibly a technological innovation helping you in a key service area) or by a difference in the external environment (such as a new service provider moving into a key service arena or changing funding requirements). A good manager not only plans but also continually reassesses those plans while maintaining openness to opportunities. The manager then evaluates these opportunities evaluated against the manager's honest appraisal of the company's strengths and weaknesses, resulting in a well-founded decision on whether to pursue the opportunity or not, and, if so, in what time span. Do not even begin this procedure until you have asked yourself this basic question: What is our organization?

(e) FINANCIAL LEADERSHIP, SUSTAINABILITY, AND THE BUSINESS MODEL. Kate Barr and Jeanne Bell identify an important distinction regarding financial leadership.18 They describe financial management as collecting data and producing reports. They state that financial leadership is guiding the nonprofit to sustainability. This is a key distinction, as many people simply ignore finances as something that is performed by experts. The financial management element requires specialized education and experience, but financial leadership is an element of fiduciary responsibility that cannot be delegated to an expert.

They go on to list eight guiding principles:

- Activate the Annual Budget. This is where the annual budget process is aligned with the annual plan (which in turn is the current element of the strategic plan). This aspect involves a desired financial outcome and engaging staff in taking responsibility for that outcome. Budget variance is emphasized and future focus is the hallmark; rather than simply hitting the current year target, recognize that the current budget is an artifice, a slice of a longer financial horizon. Use rolling forecasts as a way to shift into a future focus. Engagement and financial literacy is at the core of this principle.

- Income Diversification. The authors emphasize that income diversification needs will differ based on the type of funding streams that are already in place and that a risk determination should be made on any particular revenue stream. Will a particular revenue stream yield a surplus, or produce a deficit? The organization's capacity needs to be analyzed. Multiple payers of the same type might be a better approach than payers of different types.19 This alternate view of income diversification provides the opportunity for the nonprofit organization to sharpen its focus on core competencies and capacity and decide more strategically on funding development efforts. We shall return to this important element of an organization's “business model” later.

- Prioritize Cash Flow. In order to look forward, cash flow projections can provide a future focus, keeping the seasonality of cash flow in mind as well as the target liquidity that the organization has already set. This function may be beyond the knowledge base of the accounting department and the authors recommend that executive leadership should engage in this process. Timing of shortfalls is critical in order to control payments and in obtaining lines of credit. And, we would add, cyclical changes (changes that are multi-year in nature, ebbing and flowing with the business cycle changes of recession, trough, expansion, and peak) also require additional liquidity planning

- Plan for Reserves. The authors note that organizations that had a cushion of reserves during the recession had options and opportunities and could operate more in line with their strategic intent. Creating a reserve goal, budgeting for surpluses, and proactive planning for reserves is key. While there are rules of thumb about how much a reserve should be (we note here, formerly three-six months of expenses, but now as much as one year of expenses held in “liquid unrestricted net assets”),20 a more analytical approach is to take the organization's particular variables into account. Reserves should be used to solve temporary problems, not to fix structural deficits. Otherwise, each year's deficits are funded with amounts held in reserve, draining reserves down until they are wholly inadequate.

- Rethink Restricted Funding. There is a false dichotomy built into the idea of focusing on unrestricted funding. If restricted funding covers cost for programs that are central to your organization's mission, that funding stream acts as unrestricted funding; it is funding the core. When grant proposals are created, care should be taken to include costs that are critical to the outcome of the program and enter into a dialogue or negotiations about inclusion of those costs.

- Staffing the Finance Function. The authors describe three functional aspects of the finance function: transactional (clerical, attention to detail, knowledge of basic accounting principles); operational (range of accounting functions such as paying bills, producing financial reports, etc. – this might require a strong foundation in nonprofit accounting); and strategic (systems development, analysis and planning and communications – all CFO-level skills). Staffing might include not only employees but also contractors for organizations that have limited resources.

- Board Involvement. Provide the board with the right level of reports and analysis to keep the board high level and strategic in their thinking about finances. This includes report design (covered in Chapter 7 of this book), and creating reports that help the board with their fiduciary responsibility as well as planning and evaluation of the finance component of the organization (covered in Chapter 15).

- Managing the Right Risks. Risk assessment (covered in Chapter 14) is a critical part of financial leadership. This incorporates the idea that risk is endemic and should be prioritized by leaders. The authors advocate using an Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) system to determine current and strategic risks to the organization, looking at them from a whole systems perspective.

(f) SUSTAINABILITY. Our emphasis on target liquidity is underpinned by our belief that setting this as the primary financial objective will inevitably lead your organization to make decisions that will foster financial sustainability. At this point, it is useful to define financial sustainability since it is the essential outcome of our primary financial objective.

In their book Nonprofit Sustainability, Bell, Masaoka, and Zimmerman define financial sustainability as the ability “to ensure that the organization has adequate working capital; that is, its financial goal is to have enough money to do its work over the long term.”21 In their model, financial outcomes and mission impact form a matrix for decision making and strategic development. They describe sustainability as having two aspects: “financial sustainability (the ability to generate resources to meet the needs of the present without compromising the future) and programmatic sustainability (the ability to develop, mature, and cycle out programs to be responsive to constituencies over time).”22 This dual emphasis aligns with the notion of developing strategic directions that will ensure financial viability over time while continually assuring that the mission is being fulfilled and modified for maximum impact. The second component, programmatic sustainability, is closely tied to how sustainable the organization's business model is, in our view.

This methodology calls for a concerted effort in the planning process to engage top management and program managers with financial managers in an effort to collaborate in order to set strategic directions that align the programmatic needs of the organization with the financial requirement of ongoing liquidity (assuring cash flow over time) with maximum mission impact. This engagement strategy, if well executed, can lead to the avoidance of silos and it can result in financial leadership exercised across the organization, and not solely in the hands of financial managers.23 In many nonprofits the ED/CEO is also the functioning CFO, but even where this is not a joint function the ED/CEO must grapple with the financial and programmatic sustainability of the organization's business model.

(g) BUSINESS MODEL. We welcome the increased focus on organizational business models seen in many nonprofits. The goal is to achieve and maintain a business model that is financially and programmatically sustainable. Pursuing the primary financial objective of maintaining an approximate liquidity target is the key element of managing toward financial sustainability. Need motivation to dive in here? Consider this pitch from three former nonprofit CFOs, which links the business model together with the underlying strategy:24

Develop an explicit nonprofit business model statement. Every nonprofit has a business model, whether or not it has articulated its strategy as such. Each program and fundraising line must be managed individually, but this must be done in the context of an overall integrated business strategy. Leadership's role is to develop and communicate that overall strategy as one that brings together all the activities – which will have different financial goals – into a viable business model.

We define business model broadly and include several factors that are not normally considered in business model presentations we have seen. In a business, “…business model refers to the logic of the firm, the way it operates and how it creates value for its stakeholders. Strategy refers to the choice of business model through which the firm will compete in the marketplace. Tactics refers to the residual choices open to a firm by virtue of the business model that it employs.”25 We propose a more specific and usable definition for a nonprofit. Your business model is comprised of your organization's:

- revenue and support amounts, mix (donations, grants, fees, other earned income, dues, investment income) trend, autonomy, reliability/variability (including length and certainty of contracts and whether these are protected by an insurance or future/option/swap contract), and cash yield;

- expense amounts (which relates to your infrastructure), trend, nature (program-by-program breakdown and whether each program has revenues or support to fully cover its expenses, fixed or variable, controllable or uncontrollable, management/general/fundraising26or program-related), variability (degree of fluctuation within years and across years, hedging) and cash drain;

- asset amount, mix (liquid versus illiquid, current versus noncurrent, financial versus physical) intensity (whether growth in your operation and outreach necessitates investing in significantly more working capital, such as receivables and inventories, or fixed assets, such as buildings, equipment, and land), riskiness (environmental hazards, property and casualty risk, interest rate risk and default risk on financial assets), and cash flow implications;

- liability (loans, bonds, leases, and other forms of borrowing) amount, mix (short-term versus long-term, variable rate versus fixed rate), flexibility (early retirement or repayment without penalty, additional borrowings under agreements, presence or absence of overly restrictive covenants), riskiness (overlaps with mix factor, including interest rate risk, ability to protect against adverse developments via guarantees or a future/option/swap contract), and cash flow implications; and

- customer/client/funder value proposition. (You might consider a sixth dimension, capacity, which is defined as “the resources, skills, and functions… organization needs to fulfill its mission across multiple domains.”27 This is a subjective but important dimension.)

Every one of these five dimensions of your business model implies either a stronger, more financially sustainable organization or a weaker, more financially vulnerable organization. Correspondingly, each has implications about the ability of your organization to achieve and maintain its target liquidity level. We are not able to drill down into detail on each of these dimensions, but since we are offering two new terms not normally used in business model presentations we will define “cash yield” and “cash drain.” Think of cash yield as the amount of cash coming from your revenues, support, and gains. Cash drain would be the amount of cash that is absorbed or drained from your expenses. A great way to see the combined effects of cash yield and cash drain is to compare the operating cash flow amount from your Statement of Cash Flows to the change in net assets or change in unrestricted net assets from your Statement of Activities (see Chapters 6 and 7). The customer/client/funder value proposition is what your service or product offers to a customer or client or funder that is valued by them and that, ideally, is unique to your organization relative to other organizations with which the customer, client, or funder might contract.

The size and type of your organization and presence or absence of a sizable endowment all influence your organization's financial sustainability and health. While donative nonprofits are rightly concerned about the increased difficulty of raising funds, commercial nonprofits are not immune to threats to sustainability. A survey of private nonprofit 501(c)(3) college and university presidents finds that 73 percent of the presidents strongly agreed that the business models of the elite private universities offering doctoral and/or master's programs and having an endowment in excess of $1 billion are sustainable over the next 10 years.28 The percentage of presidents strongly agreeing with this statement for elite private liberal arts colleges having an endowment in excess of $500 million dropped to 51 percent. When asked about “other private four-year institutions,” the percentage strongly agreeing with ongoing sustainability dropped to zero (and was also zero when asked about ongoing sustainability for baccalaureate-only “other private four-year institutions”). When asked about their own college's situation, only 16 percent of presidents of baccalaureate-only private nonprofit colleges and only 24 percent of doctoral/master's private nonprofit colleges strongly agreed with the statement, “I am confident my institution will be financially stable over the next 10 years” (30 and 37 percent agreed, respectively). How do you view your organization's business model? A great topic for your next finance committee meeting, with your top paid finance staffer (if you have paid finance staff), would be to delve into the effect of your organization's size, type, and reserves and endowment levels on the financial and programmatic sustainability of its ongoing operations.

To apply the business model concept, we urge that you devote a finance committee meeting to fleshing out the five dimensions of your organization's business model. Have this exercise conducted by your organization's management team, and possibly separately by the overall board as part of your next board retreat, then compare notes. Some preliminary work needs to be done before you do the deep dive into these dimensions and their various elements. Have each finance committee member and each senior management team member answer the question, “What is our business model?”29 Then, after feeding back those statements to each participant, have them answer this question: “What is our organization's strategy for financial sustainability?” We believe that having your ED/CEO craft a “business model statement” for internal use is also a valuable exercise. We quote below three statements that focus mostly on revenues and expenses that have been crafted by Jan Masaoka:30

- Latino Theater: We produce Spanish and English plays supported by ticket sales and foundation grants, and supplemented by net income from youth workshops and an annual gala.

- Childcare Center: We provide high-quality child care for children with diverse racial, cultural, and economic backgrounds, by combining government subsidies for low-income children with full-pay tuitions, supplemented with some parent fundraising.

- Food Bank: We obtain donated food from businesses (85 percent) and individuals (15 percent), sorted and distributed largely by volunteers, and financially supported by individual donors and the community foundation.

After doing the preliminary thinking about your business model and its financial and programmatic sustainability, you will be ready to apply our five-element framework. Have your finance committee and management team try to rate each of the elements within our five dimensions as to whether that is a positive or negative factor. Agree on a summary statement for each of the five dimensions (for example, “The asset dimension represents a financially sustainable and programmatically sustainable business model because…”) for your organization. Have the finance committee chairperson and someone from your management team present their thoughts to the board for discussion and deliberation.

Once your organization's managers and board members are aware of and in agreement with the business model statement and the profile that comes out of addressing the five elements above, use the framework to assist in evaluating any proposed new program. Pose these two questions to decision makers: “Would this program help drive the delivery of our mission? Does investing in this project strengthen the success of our business model?”31 In doing so, consider whether your organization has built risk capital (for funding new product/service extensions, significant growth, new audience-broadening marketing campaigns, earned income ventures, or a new strategic direction) and whether this program is facility-intensive and therefore requires more permanent capital for funding.32 Also, measure the present organizational financial health and anticipate the after-implementation organizational financial health of the proposal.33

3.5 IMPLEMENTING THE STRATEGIC PLAN

(a) THREE STEPS IN IMPLEMENTATION. Many nonprofit organizations plan but very few excel when it comes to the implementation of those plans. Many times politics or board–chief executive dynamics, which may be disguised as “organizational realities,” get in the way. Three vital ingredients increase the likelihood of working the plan:

- Unqualified and vocal top management and board support

- Communication

- Teamwork

Both top management and the board must continue their overt support of the plan. Change is almost always resisted, so any plan that alters the status quo must be championed and the reasons for change clearly articulated.

Communication of the plan and its related program initiatives and related support elements is also essential. Most important, all volunteers, staff, donors, and regulatory authorities must remain confident that strategic initiatives are consistent with the mission and the organization's tax-exempt purpose. Also, service delivery and staff personnel must be aware of both continuing and new program directives. Gaining a sense of relative importance of the various program activities will enable people to concentrate their efforts on the key areas.

Teamwork is fostered by top management and board support as well as careful and consistent communication. In addition, teamwork can be bolstered by setting up teams. Effective use of project teams and use of employee suggestions for continuous service delivery improvement are illustrative of what can be done to harness the best elements of teamwork.

(b) CUTBACK STRATEGIES. Many times, often as a result of having set an inadequate target liquidity level, organization revenues decline and/or expenses increase, and a cash crunch occurs. Or perhaps a major funding source stops supporting the organization permanently, triggering a cash crisis – an ongoing imbalance between revenues and expenses. Either event spurs the financial management team (chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and board) to initiate cutback strategies. Illustrating, one would think that 2014, being five years beyond the “Great Recession,” would be a good year for nonprofits, right? In fact, the Nonprofit Finance Fund finds that the single greatest challenge nonprofit executives say that they are facing is “achieving long-term financial sustainability (32 percent), and documents the following financial outcomes for 2014 in its broad-based survey of nonprofits:34

- Service demand increased for 76 percent of organizations and 52% of organizations could not meet the demand with services provided;

- Almost one-half (47 percent) of organizations had a surplus (revenues and support exceeded expenses), while about one in four (24 percent) had a deficit;

- Regarding “months of expenses held in cash,” 12 percent had less than one-month worth, 35 percent had less than the minimal benchmark amount of three months' worth, and only 36 percent had the standard benchmark amount of six months' worth or more;

- For organizations selecting only one method of dealing with delays in government payments (grants or contracts), 39 percent used their own cash (reserves), 20 percent budgeted for delays in advance, and one in six organizations (17 percent) used a loan or line of credit.

Exhibit 3.3 profiles numerous strategies for coping with either a temporary cash crunch or more serious ongoing cash crisis. Notice that many of these are functional strategies – such as purchasing, facilities-related, or fundraising – rather than changes in product or service strategies.

Exhibit 3.3 Cutback Strategies

Next we examine the areas in which financial managers and financially oriented board members may contribute to strategic decision making and implementation.

3.6 PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

Managers need techniques to enable them to diagnose the fit and appropriateness of programs and service offerings. Organizational inertia in many nonprofits, particularly educational institutions and hospitals, means that programs take on a life of their own, which necessitates a disciplined method for diagnostic evaluation. As Peter Drucker notes:

All organizations need a discipline that makes them face up to reality… All organizations need to know that virtually no program or activity will perform effectively for a long time without modification and redesign. Eventually every activity becomes obsolete… Hospitals and universities are only a little better than government in getting rid of yesterday… All organizations must be capable of change. We need concepts and measurements that give to other kinds of organizations what the market test and profitability yardstick give to business. Those tests and yardsticks will be quite different.35

Action point: Make sure your nonprofit organization has rigorous tests and yardsticks to measure performance. A performance management system (such as the balanced scorecard, which is the most popular one) or strategic management system consists of “ongoing organizational mechanisms or arrangements for strategically managing the implementation of agreed-upon strategies, assessing the performance of those strategies, and formulating new or revised strategies.”36

We first provide several performance tests and yardsticks, especially financial ones, in our presentation of the balanced scorecard. We then introduce measurement tools to assist in your evaluation of service and program offerings. These tools go under various names: portfolio model, matrix, or grid. The financial manager should have a central role in helping to apply and interpret a scorecard or diagnostic model and to integrate either into the organization's strategic decision making.

(a) BALANCED SCORECARD AND DASHBOARD. The balanced scorecard is a strategic planning and management system used extensively in business and industry, government, and nonprofit organizations worldwide to align business activities to the vision and strategy of the organization, improve internal and external communications, and monitor organization performance against strategic goals. It was originated by Robert Kaplan (Harvard Business School) and David Norton as a performance measurement framework that added strategic nonfinancial performance measures to traditional financial metrics to give managers and executives a more “balanced” view of organizational performance.37 Strategies need to be reassessed from time to time for one of four main reasons:

- Even though the strategy was originally sound, insufficient resources were allocated to its implementation, so the goal/objective has not been achieved.

- The problem being addressed by a strategy has changed, necessitating a revised strategy

- The policies and strategies being implemented by this and other organizations may be interacting in unanticipated ways, prompting a review and possible revision of strategies.

- The political and cultural environment may change, causing a loss of stakeholder support and/or loss of leadership support and zeal in strategy implementation.38

In addition, we cannot manage strategies by simply reviewing past financial results. We need a method that enables us to monitor and manage the financial and nonfinancial indicators that together will drive our future operating and financial results. In short, we need a performance management system – and the balanced scorecard fits the bill.

(i) What is a Balanced Scorecard?. Businesses face the dilemma of how to manage to produce tomorrow's desired operating and financial results. Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton developed the balanced scorecard in response to this need. Kaplan revised the corporate balanced scorecard to meet the needs of nonprofit and public sector organizations that have only slightly different operating and financing objectives.

The essential principle behind the balanced scorecard system is this: Only by maintaining organizational focus on four perspectives can the organization survive and thrive in the future. These four perspectives, in turn, must have measures or metrics that are monitored and managed by decision makers to ensure that the organization stays on course.

The four perspectives are: customer, internal business systems and processes, employee learning and growth, and financial. Each of these is tied to the others by the vision and strategy of the organization, and each addresses a different question:

- Customer: “How can we create value for our donors and clients?”

- Internal Business Processes: “To satisfy our donors and customers, which business processes must we excel at?”

- Innovation and Learning: “How can we improve and change to better meet our mission?”

- Financial (or Stewardship): “How do we add value for our clients and donors while controlling costs?”39

We would rephrase the financial/stewardship perspective as: “How do we accomplish revenue enhancement and cost control while achieving our target liquidity?” Any organization that does so clearly adds value for both clients and donors.

Exhibit 3.4 illustrates a nonprofit balanced scorecard with a human services organization. The scorecard shows the objectives that this organization attached to each of the four perspectives. Beyond this, and not shown in the exhibit, the management team should develop measures, targets, and initiatives for each of the four perspectives. Paul Niven, whose book serves as the standard source for nonprofit balanced scorecards, recommends no more than 8 to 10 objectives and no more than about 20 measures.40

Source: “Vinfen Corporation's Strategy Map as Part of the Organization's Balanced Scorecard.” http://www.balancedscorecard.org/portals/0/pdf/vinfen_fy06_scorecard.pdf. Accessed: 1.4.2018. Vinfen is a leading human services nonprofit headquartered in Cambridge, MA. For related objectives, measures, and targets, see http://www.balancedscorecard.org/Portals/0/PDF/Vinfen_FY06_Map.pdf.

Exhibit 3.4 Example of Human Services Organization Balanced Scorecard

(ii) Financial Objectives and Measures/Metrics Useful for a Balanced Scorecard. The financial team's primary area of balanced scorecard development is selection and communication of the financial objectives and measures, or metrics, to gauge progress in reaching those objectives. As Robert Anderson, balanced scorecard consultant and former chief financial/chief operating officer of Prison Fellowship Ministries, notes: “Properly communicated measurements that support the [strategic] plan become powerful tools to achieve dramatic results in bringing organizational alignment, motivation and greater customer satisfaction.”41 Before developing or revisiting your organization's financial objectives and measures, collect or construct records of your organization's cash flows, reserves, financial position statements, revenue-expense statements, and endowment. Then compile a brief history of budgets, income growth, key events (including capital campaigns and large one-time gifts), and liquidity levels.42 These items will provide a backdrop for financial objective and measure development or refinement.

While some of the nonprofit scorecards or dashboards do include a liquidity target, many do not, and this is probably the single largest deficiency in scorecard implementation to date. In arts organizations, for example, the push by executive directors to achieve the artistic mission has caused some organizations to deplete almost all available liquid funds to finance short-term artistic thrusts, threatening the survival of their organizations.43 Significantly, this problem is compounded by the fact that many non-profits are very illiquid. Most nonprofit professional theaters, for example, have little endowment or cash reserves.44 Not having adequate liquid resources puts added pressure on the CEO who is already facing funding concerns:

…the most fundamental problem facing many of the leaders of nonprofit organizations is the continuing effort needed to fund and sustain financial resources sufficient to carry out the mission of the organization during a time of declining government support and intensifying competition for available funds.45

Financial objectives indicate what your organization must do well, related to finances and financial management, in order to implement your strategy. Financial measures or metrics are specific indicators that track or measure strategic success related to these financial objectives. We have already seen a social service agency's objectives; Exhibit 3.5 provides seven additional examples of scorecard financial objectives of nonprofits.

| Naval Undersea Warfare Center Newport |

|

| Dallas Family Access Network |

|

| United Way of Southeastern New England |

|

| Duke Children's Hospital |

|

| New Profit Inc. (a venture capital philanthropic fund) |

|

| Hood College |

|

| American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) |

|

Exhibit 3.5 Nonprofit Scorecard Financial Objectives

We include the first organization shown in Exhibit 3.5 to illustrate a public sector, not private nonprofit, agency. The slightly different management environment and objectives of public sector agencies possibly justifies the balanced budget target as an objective.

As far as specific measures/metrics go, here is the set of measures articulated by the fifth organization shown in Exhibit 3.5, New Profit Inc.:

- Raise $4.5 million.

- Maintain operating cash flow with 3-month surplus.

The second measure used by New Profit is clearly an approximate liquidity target (refer to Chapter 2 for more on this). Regardless of the ebb and flow of operating cash flows, the organization strives to achieve a liquidity level of three months of expenses. For many nonprofits, six months or more is ideal, depending on prefunding of maintenance expenses or new programs.

Hood College, the sixth organization portrayed in Exhibit 3.5, had these progressively aspirational measures to monitor achievement of its general objectives:

- Survive: Budget excess (deficit) as a percent of total revenues.

- Succeed: Percent increase in enrollment of students.

- Prosper: Percent increase in the quality of students of students (as measured by a quality index).

While Kaplan asserts that financial perspective items are almost always constraints rather than objectives, we believe that the two most essential financial perspective objectives are funding the mission – however stated – and achieving target liquidity levels. We agree with Kaplan that balancing the budget and achieving a slight surplus are not true effectiveness measures. Anderson documents how a short-term budget focus tends to spawn incremental thinking by staff and tends to put a ceiling on growth hopes and a floor under cost reductions.46 The Capital Care Group, one of the largest public continuing care organizations in Canada, adopted four “Healthy Finances” and “Donor Commitment” organization-level measures embodying both a short-term and long-term perspective: Sustainability, computed as ((building costs – depreciation)/annual amortization), Total cost per resident day (long-term care only), staff overtime hours, and number of donors contributing annually for the past three years.47 It then established the following Healthy finances and Donor commitment measures for each care center: total cost per day for long-term care, drug costs per day, and occupancy (in percent), total donations to sites (number, excluding corporate campaigns).48 Finance staff and board finance committee members are uniquely positioned to champion adoption of a scorecard and the appropriate financial objectives and long-term and short-term measures for it.

(iii) What Is a Dashboard?. Dashboard reports provide a one-page, graphical, usually colorful, “early warning device” for senior staff and the board, including key performance indicators and other measures of the organization's status.49 Compared to the balanced scorecard, dashboards are more user-centered (less high-level), compiling data based on organizational problems, important functions (such as development), or critical operational or business processes.50 They might be designed to deal with a single problem, may display a large number of detailed or summary measures, and might be updated hourly, daily, weekly, or monthly.51 For example, an organization's balanced scorecard could include measures such as percent donations increase and percent of development budget spent on direct mail, with the dashboard report having a development “homepage” dashboard giving a pie chart showing the percent of development budget spent on direct mail and another direct mail dashboard page with a graph on quarterly direct mail campaigns as well as percentage of premiums responded to per direct mail in each quarter. Many of the operational measures on your dashboard will not be strategic items, and therefore not show up on your balanced scorecard. That said, we have seen many of the same measures show up on dashboards as show up on balanced scorecards. You might craft, say, 20 to 35 different measures for a given balanced scorecard objective, put one or two of those measures in your balanced scorecard, then place the rest for a set of dashboards.52

To get a mental picture of a dashboard report, think of how your car dashboard provides important indicators such as gas level, speed, engine temperature, and warning lights. Indicator values are usually compared to previous values, highest and lowest values over a time period, and/or goal or benchmark (perhaps desired) values of the indicators. Arrows or traffic-signal colors (red means act now, yellow means continue to monitor, green means celebrate, you're doing great) highlight the most important changes or over- or underperformance areas. Indicators shown on your dashboard might include:

- Financial indicators such as liquidity target (maybe expressed as days of cash on hand), revenues and expenses (or maybe net surplus or deficit year-to-date compared with year-to-date budget figure), cash flow, budget projections and contributions, and days from end of month to your financial statement is completed

- Program indicators such as client/customer involvement, satisfaction measures, client progression/graduation

- Quality control indicators such as number of accidents, complaints, or mistakes

- Human resources indicators such as turnover rate, staff size and growth, and compensation53

For a college, one might include applications, campus visits, enrollments, retention, new majors or programs started, student body profile, academic quality measures, overall college financial position (cost coverage, liquidity, debt, and endowment), and development results.54 The dashboard report is a conversation starter for your executive team and board, and so needs to be inclusive of the right indicators55 (organizations use, on average, 29 indicators on their dashboards),56 present reliable and up-to-date data, and be supplemented with a brief interpretive narrative to help in sense-making.57 Develop the indicator set based on your strategic plan and unique organizational characteristics.58

(b) PORTFOLIO APPROACHES. Because of their multiple, often conflicting, objectives, nonprofits benefit greatly from diagnostic tools that help them map their programs or services in a rows-and-column format. It could be something as simple as the “BSC SWOT Analysis” grid, developed by Patricia Bush and her colleagues at the Balanced Scorecard Collaborative. Exhibit 3.6 shows the grid, as used by Niven in his consulting work. Niven contends that it highlights many potential issues and opportunities that may be translated into balanced scorecard objectives. Furthermore, by having to place each strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat into one of the four perspective boxes, the exercise provides real-time learning regarding the differences as well as overlap between the perspectives on the scorecard. The fifth column, termed “wild card,” is for any item that does not appear to fall neatly into one of the SWOT categories but is an important strategic issue.

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats | Wild Card | |

| Customer | |||||

| Internal | |||||

| Learning & Growth | |||||

| Financial | |||||

Source: Adapted from Exhibit 8.7, BSC SWOT Analysis, in Paul R. Niven, Balanced Scorecard Step-By-Step for Government and Nonprofit Agencies (Hoboken: Wiley, 2003): 173.

Exhibit 3.6 Balanced Scorecard SWOT Analysis Grid

(i) Generic Portfolio Modeling. Using some type of grid of rows and columns to visually compare an organization's various services is especially helpful for any organization that operates multiple programs or two or more earned income ventures or “businesses.” In general terms, one can place programs or services into a grid that has contribution to the mission on the vertical axis and contribution to financial viability on the horizontal axis. An example of a basic type of product portfolio map is provided by Sharon Oster in her nonprofit strategic management textbook.59 Two others that we recommend are Allen Proctor's Linking Money to Mission® Grid and The Matrix Map developed by Steve Zimmerman and Jeanne Bell.

(ii) Diagnosing the Services Portfolio. Chris Lovelock and Charles Weinberg were the first to take the concept of business product portfolios and modify them to make them useful for service strategy evaluation.60 Their model is useful for commercially oriented nonprofits, such as hospitals and universities. Every service program can be placed in one of four categories:

- Raise more funds or cut costs to support it.

- Maintain the program or spin it off as a for-profit corporation.

- Phase out the program in total.

- Phase out parts of the program.

One factor is “profitability” or cost coverage. Revenues from general fundraising campaigns are not included here, as they help offset nonspecific overhead (fixed) costs. If a cost can be linked to a specific service program, even if it is a fixed cost, it is included in the cost for purposes of this analysis. The other indicator is the extent to which the service offering contributes to the advancement of the organization's mission.

To help classify products or services as to their degree of mission advancement, it is helpful to distinguish among three distinct types: core products, supplementary products, and resource-attraction products.

Core products or services are those that have been created to advance the organization's mission. Supplementary products are often added to either enhance the appeal of the core products or to facilitate their use. A restaurant in a children's museum illustrates this.

Resource-attraction products may be developed to foster the organization's ability to attract added funds, volunteers, and other donated resources. These products are started and developed to contribute to the organization's financial solvency or liquidity. Sometimes these are called social ventures or social enterprises, or comprise activities that go under the heading “social entrepreneurship.” If an organization opens a food stand in a location other than one of its normal facilities, with the goal of making a significant amount of net revenue, this would be a resource-attraction “product.”

If an organization is operating with persistent deficits, it would try to add a venture that would support the mission at the same time that it brings in adequate revenues so that costs are covered to a greater degree. Quite often, the dual achievement of these objectives is not so easily accomplished.

(iii) Financial Return and Financial Coverage Matrix. The Financial Return and Financial Coverage Matrix (FRFCM) that we have developed is another portfolio approach. It is primarily useful for diagnosing the financial dimensions of new earned income ventures and their likely effect on the organization's liquidity target.61 For any organization having or considering adding social entrepreneurship ventures that may be mission-related and will add net revenue financially, this framework may prove helpful. As it involves financial calculations in support of capital allocation decision making, we cover it in Chapter 9, on capital project analysis. At this point, we simply note that other portfolio models share a common deficiency: None specifically incorporates the effect of programs or services on the organization's liquidity. Because liquidity is the critical component of sustainability, this is a serious deficiency that you will want to address subjectively if you use one of these models.

(iv) Three-Dimensional Portfolio Model. A recent modification and extension of the Lovelock and Weinberg services portfolio model is the Three-Dimensional Portfolio developed by Krug and Weinberg.62 Shown in Exhibit 3.7, this is an elaborate and fascinating model of nonprofit program effectiveness. In addition to the mission and financial contributions of a program, the model assesses a third dimension of “merit” – how well our organization does at performing the program.

The first dimension, at the left of the diagram, is “Contribution to Mission” – or: Is the organization doing the right things? The second dimension, on the horizontal axis at the bottom of the diagram, is “Contribution to Money,” or the degree to which a program covers all direct and indirect expenses associated with it. This is also termed “revenue/cost coverage.” Finally, the third dimension, shown extending toward the back directionally, on the far right of the diagram, is “Contribution to Merit.” This measures whether the program is high quality, with failing assigned a zero score, satisfactory a score of 5, and outstanding a score of 10. The size of the bubbles for the various programs reflects the amount of cost, or resources invested, in the program. The star that appears near the middle of the diagram is an overall composite measure encompassing all programs for this hypothetical museum.

The model's developers have interpreted it in their account of actual field experience.63

Ideally, the more programs that are located toward the back, top, and right of the cube, the better off the organization (although it is very unlikely that a program would be in this location). In organizations observed by the model's developers, subjectivity among program staff and managers regarding likely revenues and costs was an issue, and the CFO had the authority to overrule the estimates made by program staff of revenues and costs. The dialogue engendered by the application of this model to an actual museum proved valuable, as differing perceptions were brought to light.

(v) Organized Abandonment Grid® (Boschee). A final tool for enabling disciplined evaluation of ongoing programs is provided by social entrepreneurship pioneer Jerr Boschee. This Organized Abandonment Grid® is motivated by Peter Drucker's observation of inertia and the need to “sunset” obsolete programs. Exhibit 3.8 shows the grid.

For each product or service, the management team must ask two questions:

- Regardless of who pays for it or whether anyone can pay for it, how many clients in the community truly need the product or service, and how critical is their need? A “critical need” is scored a 5, “significant need” is a 4, “some need” is a 3, “minimal need” is a 2, and “no need” is a 1.

- What are the financial implications of offering this product or service? Will it result in losses, or can it be profitable?64

The grid does allow for some judgment call decisions regarding whether more resources should be allocated to the program, less resources, or none at all (eliminate the program). For those boxes labeled “probably,” for example, these programs probably deserve more resources because they are high on either their social purpose or their financial impact scale. Boschee notes that more nonprofits are now looking to earned income ventures as a primary funding source for the overall organization.

3.7 STRATEGIC PLANNING PRACTICES: WHAT DOES THE EVIDENCE SHOW?

There have been several studies of actual strategic planning practices in the nonprofit sector. A brief survey of their key findings follows.

Melissa M. Stone, Barbara Bigelow, and William Crittenden synthesized the nonprofit strategic management literature from 1977 to 1998, focusing on any real-life findings (sometimes called empirically based research studies).65 Here are their findings, beginning with the adoption and usage of formal strategic planning methods:

- Many nonprofits have not adopted formal strategic planning.

- Organizational size, board and management characteristics, prior agreement on organizational goals, and funder requirements regarding planning all correlate with whether the organization does formal strategic planning.

- Mission, structure, and board and management roles may change after formal planning occurs.

- The relationship between formal planning and organizational performance is not clear but is often associated with who takes part in the planning process (board, CEO, and possibly others) and with the occurrence of growth.

Regarding strategy content, the real-world findings were:

- Resource environments and existing funder relationships had much to do with strategic plan content.

- Nonprofits engage in cooperative and competitive strategies, with varying outcomes.

Regarding strategy implementation, Stone, Bigelow, and Crittenden found evidence that:

- External shocks cause the organizational structure to change.

- Leader behavior, the structure of authority, values, and the interaction among these items affected implementation activities.

- Interorganizational networking was important for gaining good implementation outcomes

William Crittenden also studied the strategic processes, funding sources, and growth and financial strategies used by 31 nonprofit social service organizations.66 He noted that most of these organizations were very small and very resource-constrained. His findings included:

- Organizations typified by the use of marketing and high competitor awareness tended to do better at gaining increased funding.

- Formal planning processes tend to coincide with high levels of donation funding.

- Organizations balancing their budgets and reaching their funding goals tended to also have strong marketing and financial orientations (the latter evidenced by evaluation of sources and uses of funds, revenue and expense forecasting, and predecision detailed financial projections).

- Organizations with no clear funding strategy and without strategic direction tended to falter financially.

- Nonprofit founders play an important role in an organization's strategic decisions.

- Staying focused in product/service offerings and avoiding the addition of many related or unrelated offerings are both strategically important, as was a willingness to move away from the past as direction became refocused.

More recently, Crittenden, Crittenden, Stone, and Robertson surveyed 303 nonprofit organizations to determine the linkage, if any, between strategic planning and various measures of performance. Strong relationships were not evident in the data, but the study did come out with two significant findings:

The findings also have implications for board members and executives. First, governing bodies can foster management satisfaction by formalizing the processes involved with forecasting, objective-setting, and evaluation and ensuring that the executive director is involved with these activities. Providing latitude for executives to utilize their personal leadership and decision-making style regarding non-strategic issues will also enhance management satisfaction. However, broad participation by external constituencies is needed for strategic issues involving expanding the volunteer base or adding programs. Managers can deal with external interdependence issues by using planning boards to gather and share information among outside agencies and clients. Such boards provide a buffer between managers and what might be perceived as undue intervention.67

Finally, LeRoux and Wright surveyed several hundred nonprofit social service organizations in the United States to assess the extent to which relying on various performance measures improves strategic decision making. They found evidence of a positive relationship between the range of performance measures used by nonprofits and the organization's level of effectiveness in strategic decision making. Strategic decision making was also found to be enhanced by effective governance, funding diversity, and the education level of the executive director.68

3.8 CONCLUSION

Strategic planning is a vital part of ensuring a prosperous and mission-achieving future for your organization. We have focused on the role of financial staff in the development, evaluation, and implementation of these plans. Financial personnel will stand as the first line of defense to avert financial catastrophes when the organization attempts to move too quickly or when necessary funds do not come in on a timely basis. Equally important, financial strategies and policies can be developed or revised by the finance staff. In addition, while finance staff play a central role in financial management, financial leadership incorporates the board, executive leadership, and line staff. It requires a concerted effort and an open dialogue across the organization to assure mission achievement as well as sustainable financial practices.

We conclude with a warning about balancing the role of financial position in strategic planning:

Nonprofits must resist as much as possible the tendency to make the financial situation the most important determinant of the organization's capabilities. Financial matters are an important element of the strategic plan, but they need to be balanced with other elements. At times, this may mean narrowing the scope of operations. Fulfillment of the mission is of primary importance. If the organization is on a constant treadmill of financial crises, it can easily compromise the mission in the interests of survival. But survival is meaningless if the mission is forgotten. Nonprofits should not hesitate to use the mission to say no.69