CHAPTER 9

LONG-RANGE FINANCIAL PLANNING AND CAPITAL BUDGETING

- 9.1 INTRODUCTION

- 9.2 PLANNING FOR THE FUTURE

- (a) Importance of Long-Range Financial Planning

- (b) CFO’s Role in Financial Planning and Capital Budgeting

- (c) Deferred Maintenance: A Cautionary Tale

- (d) Long-Range Financial Planning Process

- (e) Financial Planning Basics

- (f) Develop a Financial Model

- (g) Project and Reevaluate Target Liquidity

- (h) Based on Our Financial Policies and Structure, How Fast Can We Grow?

- 9.3 FINANCIAL EVALUATION OF NEW AND EXISTING PROGRAMS

- 9.4 CAPITAL BUDGETING: FINANCIAL EVALUATION OF PROJECTS THAT ARISE FROM EXISTING PROGRAMS

- 9.5 FINANCIAL EVALUATION OF MERGERS, JOINT VENTURES, AND STRATEGIC ALLIANCES

- 9.6 FINANCIAL PLANNING AND CAPITAL BUDGETING IN PRACTICE

- 9.7 CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX 9A: CASE STUDY: KIAWAH ISLAND COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION

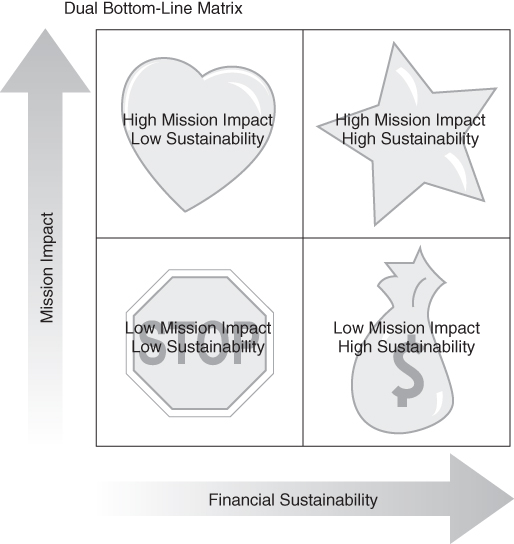

- APPENDIX 9B: EVALUATING SOCIAL ENTERPRISES

9.1 INTRODUCTION

If we consider that nonprofit boards carry a primary responsibility for the fiscal life of the organizations that they govern, then it follows that long-range financial planning is a primary method for carrying out that responsibility.1 Very often, the fiscal responsibility role is viewed within the frame of the annual budget but we postulate that nonprofit organizations need to reframe this to incorporate long-range planning.2 This chapter outlines the financial leaders' role in the long-range financial planning and capital allocation processes. Managing growth is one of the reasons organizations plan and do financial evaluations. The chapter begins by developing the financial plan for existing and already approved programs, then shows how the financial evaluation of new program alternatives such as new ventures are made. We then demonstrate how you may evaluate individual capital expenditures made as part of program implementation. A financial approach to evaluating mergers and acquisitions, partnerships, joint ventures, and strategic alliances follows. We conclude with a survey of actual practices in the areas of long-range financial planning and capital budgeting, to help you see what your peer organizations are doing.

Rhode Islanders Sponsoring Education (RISE) learned the value of long-range financial and program planning when its service demands outstripped its ability to meet those demands. A private nonprofit agency established in Rhode Island to educate the children of imprisoned women as a means of attacking the intergenerational cycle of poverty and violence, it established an 8-member committee (from its 25-member board of directors) to revisit its mission, vision statement, and goals. Then the committee established a long-range plan, which included goals, objectives, and action plans for RISE's future finances, as well as for its evaluation strategies, its role in the network of local nonprofit service providers, its public relations, and its staff and board structure. The six-page long-range plan specifies a cap on how many new students can be admitted each year to the program, with the cap based on the amount of funds raised from sponsors.

Before developing the plan, RISE (as would many nonprofits) took as many students as applied and hoped to later raise the needed funds. Equally important, the plan specified what would and would not be its core services. One of its board members, whose school also partners with RISE, praises it: “One of the beautiful things about RISE is that it doesn't try to be all things to all people.”3 Notice from this example that the strategic plan and the long-range financial plan should be consistent. As a side note, RISE also created a new associate director position, hiring an experienced Salvation Army manager who professionalized the agency by installing new systems and procedures.

Despite such success stories, some nonprofit managers and board members continue to devalue the planning process, perhaps because of (1) a philosophy that planning techniques are corporate-world methods that do not fit the values and philosophies of the nonprofit sector, (2) the often-changing nature of the environment within which they operate, (3) ignorance, or (4) a simple breakdown in their implementation of planning and evaluation techniques. Many nonprofit organizations create strategic plans but do not incorporate long-range financial planning along with program and fundraising plans. Faith-based organizations, for example, devalued planning skills in the early 1990s, partly because these techniques appeared to go against biblical admonitions to have faith and not be overly concerned about the future. Recent evidence, however, indicates this is changing, as more churches and other ministries are using long-range planning techniques.4

Executive directors/chief executive officers (EDs/CEOs) from a broad range of nonprofits indicate that, after fundraising, grant writing, and volunteer administration, the areas that they rate the highest for training needed are planning – which would include program and financial planning – and cooperative ventures.5 We address both of these topics in this chapter. Partly to deal with these sorts of knowledge/skill gaps, the Panel on the Nonprofit Sector (convened by the Independent Sector) recommends that organizations have individuals with some financial literacy on their boards.

Nonprofit financial planning was formerly limited mostly to the single-year budgeting process. This is neither strategic nor wise, but mere “bean counting.” To plan successfully, an organization must have a strategic thinker at its helm and an environment in which it infuses strategic, long-range thinking into all of its endeavors. Regardless of line and staff relations, everyone from the executive director down – and especially the chief financial officer (CFO) – must reframe their understanding of financial leadership and adopt a planning philosophy.

Planning is not just an extension of the budgeting process. It starts with good strategic planning, which identifies the key issues to which the appropriate numbers can later be attached, as we noted in Chapter 3.

We focus on formal planning, in that most business-sector studies have documented that organizations using formal plans tend to outperform those using informal plans. In the nonprofit arena, a recent study of churches indicates that those engaging in formal planning experienced greater growth in both attendance and finances.6

As nonprofits begin contracting with governmental agencies, they find that government oversight places emphasis on planning and reporting. Yet, as noted in the Indiana nonprofit survey done by Grønbjerg and colleagues, 30 percent of nonprofits refer to strategic planning as a major challenge, and 43 percent say that obtaining adequate funding is a major challenge.7 Considering these results, it is no surprise that long-range financial planning is a difficult task, one that many nonprofits choose not to undertake. But it is a vital part of proficient financial management. With that backdrop, let's turn to the long-range financial planning and capital project evaluation techniques.

9.2 PLANNING FOR THE FUTURE

(a) IMPORTANCE OF LONG-RANGE FINANCIAL PLANNING. A best practices study of community associations documented the importance of long-term financial planning, listing both a plan for major assets (long-term financial plan) and for revenues and expenses (long-term operating budget) in its profile of best planning practices:

- Establish a long-term financial plan for the association's assets (cash, accounts receivable, replacement fund, investments, etc.) that is reviewed and revised annually.

- Develop written, board-approved investment policies and procedures.

- Commission a reserve study and/or update current reserve study at least every three years and review the report annually.

- Prepare a long-term operating budget covering the next three to five years.

- Include reasonable reserves for future major repairs and replacement of common facilities in assessments as determined by the association's most recent reserve study.8

Businesses call the plan for major assets a pro forma balance sheet, and the long-term operating budget is a pro forma income statement. Think of pro forma as “projected”; its literal meaning is “as a matter of form.”

One financial policy that should be addressed periodically, as a best practice, is the specification of the levels of cash reserves held as operating reserves and as strategic reserves. Operating reserves represent money for a rainy day, and buffer against revenue shortfalls or unanticipated expense spikes. Strategic reserves may be called a building reserve in your organization – 44 percent of surveyed Denver-area nonprofits have a building reserve, for example.9 We highlight the needed total cash reserves in our discussion of the target liquidity level, one of the outputs of a well-constructed financial plan.

In addition to helping you establish the appropriate level for your target liquidity level, consisting primarily as cash reserves (including short-term investments), we see at least four other advantages for organizations that engage in long-range financial planning:

- It enables them to better determine the appropriate amount of net assets, or equity, in the organization's capital structure (which also implies how much debt the organization may carry; see Chapter 10).10

- They more fully benefit from strategic planning, and are able to mesh the strategic plan with financial policies and decisions and with yearly operating budgets. This is key in producing plans that are achievable and can lead to sustainability.

- It enables them to portray themselves as well-managed organizations to banks, bond investors, and foundations and agencies providing government grants; in fact, one consultant counsels philanthropists that one way to reduce the risk of their investment in nonprofits is to ensure that recipient organizations are implementing “financial plans for the long-term health of the organization.”11

- These organizations are better able to determine a reasonable growth rate for the organization's activities.

A late 2005 survey of Oregon-based nonprofits found that, even though fundraising efforts were deemed successful, 30 percent of the nonprofits were forced to reduce services to meet operational costs, and most nonprofits were concerned about rising healthcare costs for employees, increased costs of other insurance, and increased regulation for nonprofits.12 Anticipating negative trends such as these, by including their likely effect on the organization's financial position, would not only cause the nonprofit to hold a higher target liquidity level (to avert service cutbacks), but also help the organization prepare itself for the possible cost increases that lie ahead. The financial plan helps your organization see the effects of these trends on its financial position.

(b) CFO'S ROLE IN FINANCIAL PLANNING AND CAPITAL BUDGETING. In his classic article “Strategy for Financial Emergencies,” Gordon Donaldson declares, “[T]he financial executive's primary managerial responsibility is to preserve the continuity of the flow of funds so that no essential decision of top management is frustrated for lack of corporate purchasing power.” Although written for business financial executives, Donaldson's assertion applies equally to nonprofit finance officers. The board treasurer and the organization's CFO share responsibility for ensuring that the nonprofit plans its financial future and allocates scarce capital to the best uses. Regardless of whether the treasurer is the CFO, he or she retains ultimate responsibility for these processes, so at a minimum the treasurer must oversee this important aspect of proficient financial management. As we have emphasized, doing this includes projecting the organization's liquidity and accumulation of or maintenance of the target liquidity level. It also entails working closely with your chief development officer, assuming your revenues include annual or deferred giving. Beyond this, there are several key components to the CFO's responsibility:

The CFO's role seems to be threefold. First, as part of the senior management team, the CFO contributes fully in overall strategic planning for the organization, always with an eye on the financial ramifications. The second role is to drive the capital planning process, maintain the rigor around assessment, keep everyone honest, and serve as “quarterback” of the capital planning team. The third role is the quantitative role: understand debt capacity, provide a consistent methodology for assessing return on individual projects, and generally support the decision-making process.13

We developed the strategic planning role in Chapter 3, and we shall return to evaluating debt capacity in the next chapter. Our focus in this chapter is to spell out the long-range financial planning process and the capital budgeting process.

(c) DEFERRED MAINTENANCE: A CAUTIONARY TALE. Before entering into the long-range planning process, the CFO should evaluate the issue of deferred maintenance. The pressure on annual budgets to reduce costs often creates conditions where the organization decides to continue to operate aging assets while deferring maintenance costs and investments in new assets. This deferral may provide short-term budget relief, but an assessment of the risk involved in such a deferral should be undertaken in order to understand the long-term implications.14 The financial evaluation of risk looks at the annual operating costs as well as the potential fixed asset investment all within the more strategic context. In any case, deferred maintenance can have a detrimental outcome that must be carefully evaluated before such a decision is made.

(d) LONG-RANGE FINANCIAL PLANNING PROCESS. Financial projections covering the next five years are developed in an exercise called long-range financial planning. These projections should be done periodically as part of the organization's strategic planning process. The main financial planning document should be based on all current programs as well as those future programs already approved. Later, planning scenarios can be developed to bring possible new programs or ventures into the picture. The purposes of the long-range financial plan are:

- To tie financial resource requirements to the strategic plan (recalling both the enabling and constricting functions of finance)

- To identify any future period with fund surpluses or, much more commonly, fund shortfalls

- To determine approximate funding needs for the shortfall periods, which is the essential information the executive needs for planning capital campaigns, other special fundraising appeals, and endowment building

- To identify the seasonal and cyclical aspects of the organization's cash flows

- To bring together in one place all the interacting sources and uses of funds experienced by the nonprofit organization: operating, investing, and financing cash flows (which reflect your organization's “business model” – refer back to Chapter 3)

- To build a financial contingency plan, or what Donaldson terms “a strategy for financial mobility”

We cannot emphasize too strongly the importance of doing a long-range financial plan. Not only will such a plan help a strong organization to become stronger, but it may spell the difference between survival and financial failure and dissolution for your organization. Often nonprofit organizations do a good job of selecting programs, but then fail to plan for the financial requirements of implementing those programs, leading a number of these organizations – especially private colleges – to fail.15

Averting a financial crisis from too-rapid or ill-advised expansion is well worth the expense and effort of long-range financial planning. An example to emulate here is Cedarville University (Cedarville, Ohio), which uses its strategic planning process to implement “managed growth.” Our chapter-opening vignette of RISE is another positive example.

Further, where programs are vital to the organization's mission but the financial plan indicates significant shortfalls, the ED/CEO is stimulated to search for other organizations to help share the load. Resource sharing may take place through a merger, acquisition, joint venture, or strategic alliance.

The degree of sophistication and level of detail in nonprofit organizations' financial planning varies. Many small organizations, and quite a few larger ones, do no formal long-range financial planning; this situation tends to indicate an organization whose overall financial administration process is poorly managed. Our Lilly study found that organizations not using “present and anticipated financial positions” to guide programmatic decisions tended to be those deficient in overall financial management.

Some of these organizations may even engage in strategic planning, but are in the dark about the funding feasibility of these plans and whether they need to begin arranging financing now or whether they can self-finance the program. Capital campaigns cannot be initiated and executed quickly. Other organizations have sophisticated, computerized financial models. Mostly these are larger organizations that can afford to devote staff and computer resources to the task or hire an outside consultant to develop the model. Many organizations, even those otherwise proficient in their financial management processes, fail to anticipate key events that could alter the future financial position of the organization. As a result, these organizations have no strategy for dealing with those events if and when they occur and no financial model with which to project cash flow. At bottom, proficient financial managers anticipate what could be, not merely what they think is the most likely financial future.

(e) FINANCIAL PLANNING BASICS. Here's a simple approach to use to get started in financial planning. It is based on three vital inputs:

- The most recent three years of financial statements

- The capital budgets for the next five years, insofar as they are known. This should also include a lease-versus-purchase analysis for all assets under consideration. Leasing and alternative financing sources are covered in Chapter 10.

- Management and board financial policies regarding investments, debt, and minimum necessary liquidity

How might your organization assess its future capital spending needs? The best general approach is to first specify several categories of the external environment that will affect your organization's future (e.g., competition or regulations), then identify the specific external drivers that will be at work within those categories and that have relevance to your industry (e.g., youth services or performance arts). Then specify the internal goals that will best suit your organization to meet those anticipated developments in the external environment. Finally, detail the capital responses that your organization will have to make to achieve those internal goals: new or refurbished plant or equipment, enhanced information technology, renovation, expansion, upgrades to systems, training investments, increased research and development expenditures, multiyear brand- and image-building investments, and so on. Consult Exhibit 9.1 for a filled-out schematic for the hospital industry. The “shifting regulated and negotiated payment incentives” fits in the Technology/Regulation section as well, particularly regarding the dynamics around Medicaid.

Responses to External Drivers of Capital Need

| Category | External Drivers | Internal Goals | Capital Responses |

| Competition |

|

|

|

| Technology/Regulation |

|

|

|

| Consumers |

|

|

|

Source: Financing the Future, Healthcare Financial Management Association, Used by permission.

Exhibit 9.1 Capital Planning Example Using the Hospital Industry

Armed with these inputs, the financial manager can obtain or develop operating forecasts that will enable the formulation of simple long-range financial plans. Although the next year may be somewhat detailed (depending on whether the operating budget has been developed yet), years 2 to 5 will show little detail – possibly only total revenue and total expense of operations.

The example that follows illustrates the long-range financial plan and the fact that the planning process, when used properly, takes at least two passes or iterations. The first pass takes the strategic plan and preexisting funding strategies as givens and determines each future year's funding surplus or shortfall. The feedback from this exercise provides the organization's managers and board with needed input for possible revisions of the strategic plan and/or the funding strategy, which is the second pass.

To the extent surpluses appear in forward years, the management team can choose whether to:

- Develop program initiatives (expand present programs or add new ones)

- Reduce debt

- Increase investment in existing staff or technology

- Build liquidity (if appropriate, based on financial policies)

Where shortfalls appear, organizations can choose whether to

- If they have large cash reserves, draw these down

- Reduce discretionary expenses

- Redirect funds from noncore to core (essential to mission) programs

- Sell investment securities from portfolio

- Initiate capital campaign (if capital spending is the reason for the shortfall)

- Increase interest revenue through the use of appropriate investment vehicles and/or building of endowment

- Increase rental and/or unrelated business income revenue

- Increase investment in fundraising for operations – annual campaign

If there are perpetual problems with shortfalls, permanently reduce expenses and work to initiate or increase investment in planned giving fundraising or make other business model changes.

At a minimum, do a projection of the statement of cash flows (SCF) (you may wish to refer to Chapter 6 for a review of this statement). To keep things even simpler, enter the last five or six years of statement of activities data into a computer spreadsheet. Then let the spreadsheet program do a straight-line projection of total revenue (income) and expenses. Exhibit 9.2 shows such a projection using the actual financials of an anonymous ministry organization.

| Statements of Activities of a Nonprofit Organization | |||||||||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Projected 2018 | Projected 2019 |

Projected 2020 |

Projected 2021 |

Projected 2022 | |

| Income: | |||||||||||

| Contributions | $5,121,652 | $5,088,913 | $5,721,854 | $5,725,263 | $5,852,144 | $6,618,502 | $6,665,790 | $6,945,143 | $7,224,496 | $7,503,849 | $7,783,202 |

| Net gain on disposal of fixed assets | 29,733 | 214,717 | 85,714 | 34,816 | 42,641 | 78,749 | |||||

| Investment income | 193,319 | 194,318 | 227,973 | 275,187 | 279,756 | 364,352 | |||||

| Sales less cost of goods sold | — | — | — | 128,116 | 142,991 | 149,530 | |||||

| Total Revenue & Support | $5,344,704 | $5,497,948 | $6,035,541 | $6,163,382 | $6,317,532 | $7,211,133 | $7,286,914 | $7,627,449 | $7,967,985 | $8,308,520 | $8,649,055 |

| Expenses: | |||||||||||

| Program Activities: | |||||||||||

| Church growth, evangelism | $1,618,616 | $ 1,409,014 | $ 1,526,571 | $ 1,678,493 | $ 1,873,124 | $ 2,456,467 | |||||

| Media, translation | 548,411 | 469,713 | 575,519 | 697,491 | 875,791 | 785,726 | |||||

| Theological, church leadership training | 404,940 | 356,640 | 414,600 | 410,305 | 360,691 | 289,019 | |||||

| Education | 272,770 | 199,141 | 217,979 | 246,747 | 334,175 | 302,764 | |||||

| Field administration | 207,196 | 192,317 | 228,145 | 297,591 | 347,325 | 291,803 | |||||

| Appointees | 206,719 | 209,831 | 133,666 | 108,690 | 108,726 | 94,001 | |||||

| Homeland ministries, furlough | 671,830 | 760,737 | 726,156 | 615,136 | 743,129 | 866,198 | |||||

| Relief | 96,276 | 44,915 | 118,758 | 192,541 | 133,910 | 434,442 | |||||

| Service to missionaries | 71,872 | 59,049 | 137,027 | 135,292 | 182,386 | 137,644 | |||||

| Medical | 40,448 | 41,616 | 38,114 | 27,428 | 57,871 | 40,639 | |||||

| Subtotal: | |||||||||||

| Program exps. | $4,139,078 | $ 3,742,973 | $ 4,116,535 | $ 4,409,714 | $ 5,017,128 | $ 5,698,703 | $ 5,712,065 | $6,052,459 | $ 6,392,852 | $ 6,733,246 | $7,073,639 |

| Supporting activities: Management | |||||||||||

| and general | $ 814,414 | $ 996,659 | $ 864,530 | $ 1,046,032 | $ 1,149,552 | $ 1,210,873 | |||||

| Fundraising Subtotal: | 81,585 | 140,880 | 193,685 | 188,453 | 199,089 | 172,759 | |||||

| Support exps. | 895,999 | 1,137,539 | 1,058,215 | 1,234,485 | 1,348,641 | 1,383,632 | $ 1,501,193 | $1,593,985 | $ 1,686,778 | $ 1,779,570 | $1,872,363 |

| Total expenses | $5,035,077 | 4,880,512 | 5,174,750 | 5,644,199 | 6,365,769 | 7,082,335 | 7,213,258 | 7,646,444 | 8,079,630 | 8,512,816 | 8,946,002 |

|

Excess (deficiency) of income over expenses |

309,627 | 617,436, | 860 791 | 519,183 | −48.237 | 128.798 | 73.656 | (18,995) | (11 1,6 451) | (204,296) | (296,947) |

| Unadjusted net assets — end of year* | $4,388,295 | $ 5,005,731 | $ 5,866,522 | $ 6,385,705 | $ 6,337,468 | $ 6,466,266 | $ 6,539,922 | $6,520,927 | $ 6,409,282 | $ 6,204,985 | $5,908,039 |

* Shows what net assets would be without adjustments or transfers.

Source: This table uses actual data for a ministry organization, but the organization's name has been withheld and the years changed. Projections were done by author using Microsoft Excel. This is done by simply entering the numbers shown for contributions, then highlighting the range, and clicking and holding down the drag handle on the bottom right of the range and dragging it to the right over several cells.

Exhibit 9.2 Financial Projection Providing Early Warning of Financial Deterioration

Notice the deteriorating trend; if the trend had continued, the organization would have ended up out of business. Simply knowing that this is what will occur if corrective action is not taken is well worth the time and effort of the entire planning exercise. If you were the CFO of this organization, and its financial policies rule out the use of short-term debt, how might you close the gap in future periods?

As you reflect on the situation, you will likely identify three situational factors that generally act as constraints on your actions:

- You cannot draw down liquidity without violating the minimum liquidity financial policy (target liquidity level).

- Short-term debt is forbidden (not uniformly but commonly, in nonprofits).

- All programs are core (so no program may be eliminated or severely curtailed).

The financial manager might recommend these possible courses of action to the ED/CEO and the board:

- Reduce discretionary expenses.

- Increase the investment in fundraising.

- Increase rental and unrelated business income.

- To the extent possible, shift investment portfolio to higher-yield investment vehicles (within risk parameters) and/or, once you get large enough, build endowment.

- Revisit the minimum liquidity target to see if it should be set higher in the future.

The planning exercise is valuable because when shortfalls are projected, they provide early warning of impending financial shortages, and when surpluses are expected, we may consider opportunities to expand or enhance the mission or build endowment. Furthermore, as noted earlier, you may engage in contingency planning, selecting for further study events that are not expected. Although they are not considered “most likely,” and therefore are not incorporated into your normal financial plan, these events may still be quite probable and they could have a significant impact on your revenues, expenses, assets, or liabilities. High-profile natural disasters would be a prime example. These typically siphon off significant donation funding from many non-relief US nonprofits, especially food banks, homeless shelters, and after-school programs.16

(f) DEVELOP A FINANCIAL MODEL. The next phase in your financial planning process is to develop a full-blown financial model of your organization, its operations, its asset requirements, and how these will be financed. A financial model may be defined as “the financial representation or model of how an organization works and functions, created in such a way that it can productively be used as a means to simulate the real world.”17 This more complete portrait of your organization's financial future adds significant value to the simple forecast we profiled earlier by:

- Showing asset requirements of growth (or scale-backs), along with the need for financing those asset requirements, by projecting key aspects of the statement of financial position (SFP).

- Incorporating relationships between the various financial accounts into cause-and-effect relationships, which is easily done even in a financial spreadsheet model.

- Showing the true effects of revenue, expense, liability, and net asset changes on the target liquidity level, by backing out noncash effects of depreciation, amortization, and other accounting adjustments such as losses on discontinued operations or restructuring charges.

- Identifying knowledge and information gaps that must be addressed for the organization to have a better understanding of its financial interrelationships and cash flows – some of which will be discovered in the processes of modeling points 1, 2, and 3. Others will be unveiled as banking, payment system, and regulatory policies and constraints (Chapter 11) are built into the model and as loan covenants (Chapter 10) and restricted cash and other restricted net assets are identified in the model.

- Allowing a view of the financial position, funding need, and revenue coverage of expense changes when any single input to the model changes in value. This what-if scenario analysis function is the most valuable feature of a financial model, in the view of most users. See Appendix 9A for an example.

It is beyond our scope to go into detail on the hows of financial modeling, and there are print and Internet sources to help you to develop a model.18 We use a publicly available financial planning model developed by PricewaterhouseCoopers for service businesses to show you the level of detail and interaction between your forward-year projections.19

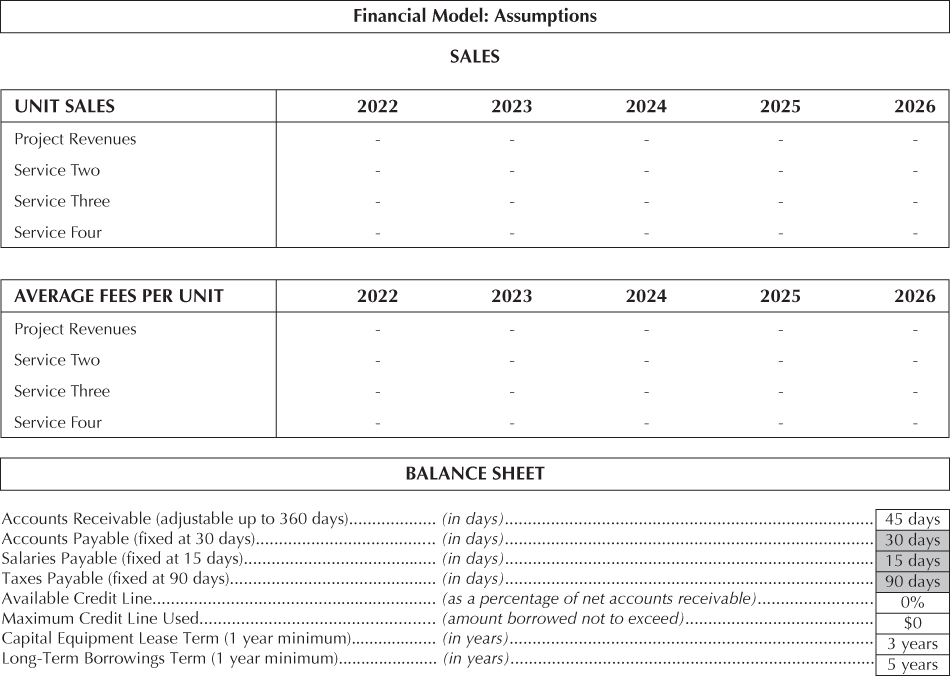

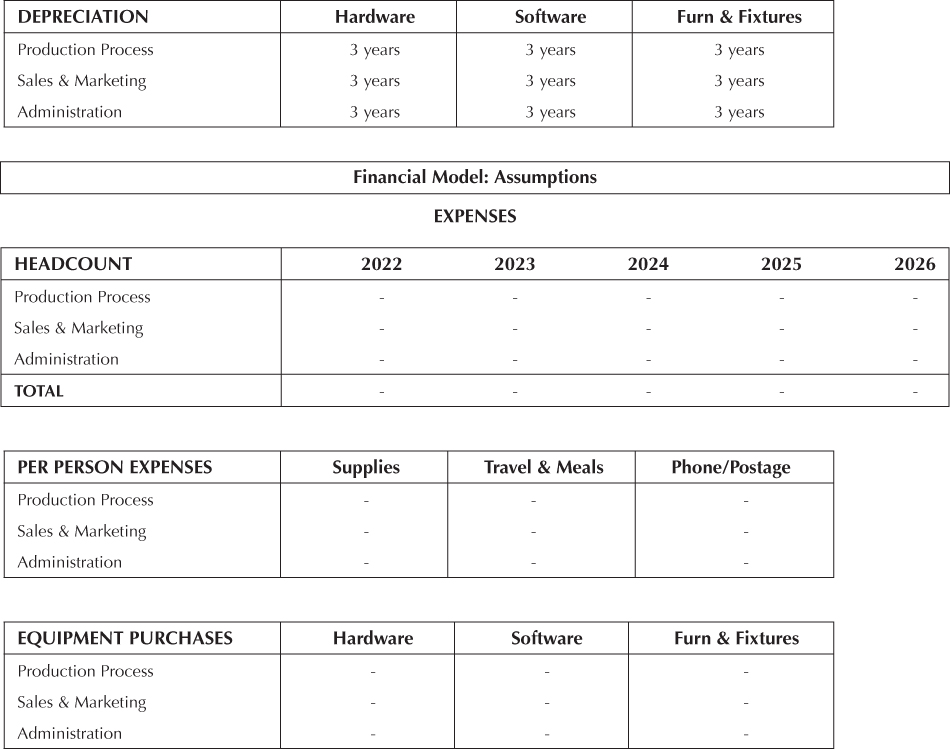

Exhibit 9.3 shows the set of assumptions that go into the financial model. Many items are computed as a percent of sales, or total revenues.

Exhibit 9.3 Financial Model Assumptions – Service Business Example

Next we see our first projected financial statement, the Income Statement (Exhibit 9.4). It is similar to the nonprofit statement of activities. As you study it, note the level of detail that is appropriate for your long-range financial plan. You may wish to customize it with your organization's Statement of Activities captions, or use it as is if you are projecting for a for-profit subsidiary that is involved in generating unrelated business income.

Income Statement (SA) ($)

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | |

|

Revenue Project Revenues |

$0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Total Revenues | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

|

Operating Expenses Production Process |

$0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| % of Revenues | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Sales & Marketing | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| % of Revenues | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Administration | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| % of Revenue | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Total Operating Expenses | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| % of Revenue | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Interest Expense | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Interest Revenue | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Income Before Taxes | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Tax Expense | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Net Income (or Surplus) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| % of Revenue | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers. © 2005 PricewaterhouseCoopers. All rights reserved. PricewaterhouseCoopers refers to the network of member firms of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each of which is a separate and independent legal entity. Downloaded from: www.pwcv2rform.com. Accessed 1/2/06. Used by permission.

Exhibit 9.4 Projected Revenues and Expenses – Service Business Example

Note that the Net Income would be the Change in Net Assets for a nonprofit organization and that tax expense (Tax Exp) will most likely be zero for tax-exempt nonprofits (unless they have to pay some use or excise taxes or taxes on unrelated business income).

Next, we need to project the SFP, or balance sheet. Notice in Exhibit 9.5 the service business projected balance sheet developed by PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Again, you would modify it to the account categories for your organization, including a breakdown in “Cash” for unrestricted cash and restricted cash. The caption “A/R” is an abbreviation for accounts receivable, which would fit commercial nonprofits but might instead be pledges receivable for the donative nonprofit or grants receivable for other nonprofits.

Balance Sheet (SFP) ($)

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | |

|

ASSETS Current Assets: |

|||||

| Cash | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Net Accounts Recv | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Total Current Assets | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Gross Fixed Assets | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Less Accum Depreciation | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Net Fixed Assets | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| TOTAL ASSETS | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

|

LIABILITIES Current Liabilities: |

|||||

| Accounts Payable (30 days) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Salaries Payable (15 days) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Taxes Payable (90 days) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Line of Credit (X% of net A/R) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Current Portion of Cap Equip Lease | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Current Portion of Long-Term Debt | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Total Current Liabilities | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Long-Term Liabilities: | |||||

| Capital Equipment Lease (3 years) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Long-Term Debt (5 years) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Total Long-Term Liabilities | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| TOTAL LIABILITIES | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Net Assets | |||||

| Without Donor Restriction | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| With Donor Restriction | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Total Net Assets | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| LIABILITIES & NET ASSETS | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers. © 2005 Pricewaterhouse Coopers. All rights reserved. PricewaterhouseCoopers refers to the network of member firms of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each of which is a separate and independent legal entity. Downloaded from www.pwcv2rform.com. Accessed 1/2/06. Used by permission.

Exhibit 9.5 Projected Assets, Liabilities, and Net Assets —Service Business Example

We modified the business format slightly. For Equity, we use Net Assets, and you may also wish to split out Unrestricted Net Assets, Temporarily Restricted Net Assets, and Permanently Restricted Net Assets rather than Net Assets with Donor Restrictions and Net Assets without Donor Restrictions.

Finally, and for many organizations possibly the most important projection, is the sources and uses of funds projection. It is similar to a projected SCF, and you may opt to use your SCF format rather than the sources/uses template shown in Exhibit 9.6. Regardless, study it carefully, noting how the financial plan details the needs for funds and the anticipated funding sources. You may leave one category in the latter blank (zero value), using this as the “plug figure” for your projected long-range financial plan. Then strategize on how to meet that shortfall as you view the first-pass projection of your sources and uses. That leads us directly to the target liquidity level assessment, our next topic.

Statement of Sources & Uses ($)

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | |

| BEGINNING CASH | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Sources of Cash | |||||

| Net Income | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Add Depr/Amort | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Accounts Payable (30 days) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Salaries Payable (15 days) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Taxes Payable (90 days) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Additions to Line of Credit | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Additions to Cap Equip Lease | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Additions to Long-Term Debt | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Total Sources of Cash | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Uses of Cash Less Changes In: | |||||

| Net Accounts Rec | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Gross Fixed Assets | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Reductions to Line of Credit | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Reductions to Cap Equip Lease | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Reductions to Long-Term Debt | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Total Uses | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| CHANGES IN CASH | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| ENDING CASH | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers. © 2005 PricewaterhouseCoopers. All rights reserved. PricewaterhouseCoopers refers to the network of member firms of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each of which is a separate and independent legal entity. Downloaded from: www.pwcv2rform.com. Accessed 1/2/06. Used by permission.

Exhibit 9.6 Projected Sources and Uses of Funds – Service Business Example

What is the bottom line on the sources and uses of funds projection? Ending cash. If the total of the anticipated sources of cash are inadequate to cover anticipated uses of cash, your ending cash will be eroded over time. Move now to arrange additional sources of funds or reduce anticipated uses of funds to bridge the gap between sources and uses. Furthermore, many organizations will want to intentionally plan to have a smaller total-uses-of-cash figure, in order to build toward higher values of ending cash as it targets a higher liquidity level.

(g) PROJECT AND REEVALUATE TARGET LIQUIDITY. Earlier in this book we profiled evaluating the necessary level of liquidity (Chapters 2, 5 , and 8) and how to measure liquidity (Chapters 2 and 7). Equally valuable is an analysis of the target liquidity level that is based also on the projected financial position several years in the future. In this way, we not only know what level of operating reserves to hold, but also the level of strategic reserves to hold. Strategic reserves include amounts accumulated to prefund capital expenditures, funds for unanticipated strategic options (such as new programs or large one-time service needs that may arise), and funds for a board-designated endowment, or quasi-endowment, the income from which may help fund program expenses. These additional funds are necessary because nonprofits typically do not earn enough of a surplus (“profit”) of revenues over expenses to self-fund such expenditures on a timely basis.20

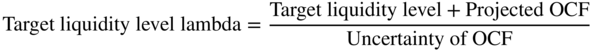

The beginning point for this analysis is the Ending Cash projection we looked at in our sources and uses projection (refer to Exhibit 9.6). Recall, from our ratios presentation in Chapter 7, the definition of target liquidity level and also a related ratio, target liquidity level lambda:

Total amount of credit line is the ceiling amount approved for the bank, or the maxi- mum amount that may be borrowed at any one time. It is similar to the credit limit on a credit card.

where:

| Projected OCF is the operating cash flow amount for the next year |

| Uncertainty of OCF is the standard deviation of the organization's historical operating cash flows (OCFs) for at least the past three years |

The first thing we add to Ending Cash is the amount held in short-term investments. Notice on our projected balance sheets (refer to Exhibit 9.5) that no line item was listed for short-term investments. If your organization has short-term investments (beyond cash and cash equivalents, with cash equivalents being very short-term investments with a maturity at the time of purchase of three months or less), you should list those on your projected balance sheet immediately below the cash row. Then determine the total amount of your organization's negotiated credit line, if any, and add this to the total you had for (Ending Cash + Short-term investments). This amount will not be shown on your projected balance sheet except in the special case in which you plan to have borrowed up to the limit of that credit line at the balance sheet date, say, 12/31/2022. Your organization will find that one of the primary benefits of projecting a balance sheet is to know how much of a credit line to request from a bank. For comparison purposes, if you need to determine what another peer organization has arranged in a past year for its credit line you would have to search the notes that accompany the financial statements to find the total amount of the credit line. Finally, subtract also from your projected balance sheet any amount shown under current liabilities for “Credit line” or an equivalent current liability entry, normally “Notes payable.” This represents amounts borrowed under a credit line or similar short-term borrowing arrangement with a bank or other short-term lender.

For example, let's say you project Ending Cash of $5,000, short-term investments of $15,500, have arranged a credit line for $100,000, and project a borrowed amount of $45,000. Your projected target liquidity level would be $75,500 (= $5,000 + $15,500 + $100,000 − $45,000).

If your organization typically has significant across-year variability in its operating cash flows (consult your last five SCFs to check this), you will also want to calculate the projected TLLL, or projected target liquidity level lambda, which involves two modifications to the formula: (1) add the next year's projected operating cash flow to projected TLL and then (2) divide the sum from step 1 by the standard deviation of your organization's historical operating cash flows.

Revisiting our previous example, let's say your organization expects an operating cash flow for the next year of −$35,000 and has these historical operating cash flows for the past five years:

| PAST YEARS | OPERATING CASH FLOW |

| 1 | $45,000 |

| 2 | −25,000 |

| 3 | 5,000 |

| 4 | −15,000 |

| 5 | 10,000 |

Clearly, your organization has experienced significant variability in its OCFs. We need to calculate the standard deviation of this sample of cash flows to use in our calculation of projected TLLL. Let's illustrate that calculation by using Microsoft Excel and the built-in function for sample standard deviation:

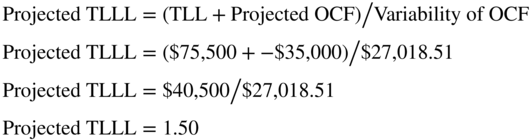

Using this sample estimate for our OCF variability, we get this projected TLLL:

If your organization's OCFs are approximately normally distributed (appearing as an almost symmetrical, bell-shaped curve when graphed), we can use this information to estimate our probability of running out of cash.

First, let's assume that “out of cash” is a negative cash balance. This implies we exhaust our Ending Cash, then exhaust our short-term investments, then use up any previously unused credit line availability, and finally burn through any positive OCF that comes in the next period.

Second, in our illustration, next year's projected OCF is forecasted to be a negative $35,000, which we noted should drop our TLL to $40,500. Based on historical OCF variability (a standard deviation of $27,000 plus), what is the chance we will drop below $0 in cash next year? We take the difference between $0 and our forecast of $40,500 (= TLL + Projected OCF), and divide that by $27,018.51. This gives us how many standard deviations $0 falls below our $40,500 forecast, which is actually called a “z score” in statistics:

Notice that this figure is exactly the same as our projected TLLL.

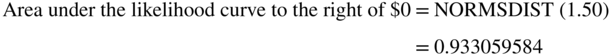

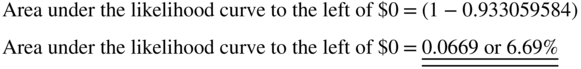

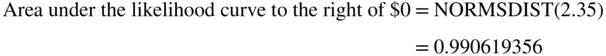

The question is now: What is the probability of our liquidity dropping not just below $40,500, but below $0, in the forthcoming period? The TLLL number of 1.50 tells us that $0 is 1.5 standard deviations below the expected value of $40,500. Visually, looking at Exhibit 9.7, one-half of the possible outcomes fall above $40,500, so these would represent 50 percent of the outcomes, or a 50 percent likelihood. To determine how likely an outcome below $0 is, we need to determine the likelihood of an outcome falling between $0 and $40,500, then add that to the 50 percent likelihood of an “above $40,500” outcome, and finally subtract this sum from 100 percent. We can consult a standard normal table to get the likelihood of the $0 to $40,500 outcome, or use the NORMSDIST function to do this for us, using Excel. We start by getting the probability of getting an outcome above $0:

Therefore:

Exhibit 9.7 Distribution of Target Liquidity Level Outcomes Using Hypothetical Example

Interpretation: This calculated value for the area suggests that the chance of our organization running out of cash is less than 7 percent for the upcoming year.

We may decide this probability of running out of cash is too high. If we were to plan based on a slightly larger credit line, say $123,000 instead of $100,000, our TLL jumps $23,000 to $63,500. That gives us a TLLL of 2.35 = $63,500/$27,018.51.

Let's see how this revised credit line amount affects our probability of running short on cash.

Therefore:

The board and CFO may find a probability of less than 1 percent to be acceptable. We see here the value of iterative and interactive financial planning, whereby different values can be plugged in for target liquidity and the preferred policy decision selected. In this case, the organization decided its original TLL was too low and bumped it up by $23,000. It would not have necessarily done this by increasing the credit line amount, however, and may have (given sufficient lead time in the planning process) built up the level of short-term investments instead.

(i) Scenario Analysis and Sensitivity Analysis. Running various scenarios through your financial model to see their likely effect on revenues, expenses, assets, liabilities, and the target liquidity level is very helpful. If you are not prepared to do this scenario analysis, at least vary your revenues up and down by 5, 10, and 15 percent to see the effect on your financials, and do the same with expenses. You may wish to develop or use an Excel revenue scenario template to help you see the results of varying revenue and support levels.21

We agree with Donaldson that an organization needs a database for a strategy of funds mobility in order to cope with unexpected changes. The advice of consultant Hilda Polanco is on point: “Discuss and develop plans for mitigating any financial risks demonstrated by the scenarios, including specifying “triggers” for implementing plans.”22 In Exhibit 9.8 we present a template modified from Donaldson's business template. It lists items as uncommitted reserves, reduction of planned outflows, and liquidation of assets. This template is related to the tiers of liquidity that we presented in Exhibit 2.2 in Chapter 2; you may wish to review that diagram before going any further. In Exhibit 9.8, we see an estimate of funds that could be made available from both internal and external sources. Note that these are funds that have not already been committed for use in the next three years. These include:

| Available for use within: | |||

| Resources | Three months | One year | Three years |

|

I. Uncommitted reserves Instant reserves Surplus unrestricted cash Unused line of credit Negotiable reserves Additional bank loans Unsecured (no collateral) Secured (have collateral) Additional long-term debt Additional funds raised* II. Reduction of planned outflows Volume-related Change in production or service schedule Scale-related Marketing/promotion program R&D/New program development budget Administrative overhead** Capital expenditures Value-related Fundraising expenditure** Capital campaign** Endowment campaign** III. Liquidity of assets Shutdown (temporary) Sale/divestiture of unit SUBTOTAL TOTAL RESOURCES |

$ $ $ $ $ $ |

$ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ |

$ $ $ $ $ $ |

* It is unusual to be able to raise more funds the same fiscal year when increasing fundraising efforts, although some organizations (especially faith-based organizations) are able to do this at times.

** Generally, pare back or defer, but do not eliminate entirely. If “Additional funds raised” is a Level I objective, this will preclude cost reductions in one or more of the fundraising categories.

Source: Adapted from Exhibit I in Gordon Donaldson, “Strategy for Financial Emergencies,” Harvard Business Review (November/December 1969): 67–79. Used by permission.

Exhibit 9.8 Inventory of Resources for Financial Mobility—a Template

- Uncommitted reserves. This includes instant reserves and negotiable reserves:

- Instant reserves (unrestricted cash balances, unrestricted short-term marketable securities, and the unused portion of the bank credit line, if any) are instantly available for any purpose. Buy time for the organization in order that it can mobilize other resources – implying that the size of the instant reserves should be larger the larger an unexpected cash deficit might be and the longer it takes the organization to tap other resources.

- Negotiable reserves (new short-term bank loans, new long-term debt issues, new fundraising approaches or intensity) involve some form of negotiation and are therefore less certain. Also, the amounts depend on the degree and type of previous use of these items (long-term debt issues depend on previous use of long-term debt and short-term debt). Consider the sequencing and interrelationships in this category of funding sources.

- Collateral for short-term loans is typically inventory and accounts receivable (ruling out this form of borrowing for many nonprofits), although at times grants and contracts receivable may serve as security for loans.

- Reduction of outflows. Here the view is toward what existing commitments to planned outflows may be reduced and a consideration of whether an unexpected need that arises might better be met through one of these reductions rather than drawing on uncommitted reserves – the wisdom of which depends on how large and pressing the need is, the size and accessibility of the organization's reserves, and the special circumstances related to the unexpected need.

- Value-related expenditures are not directly related to the organization's services, but do affect the donor franchise and donors' perceived value (such as expenditures on an ongoing capital campaign).

- The largest potential fund source here is usually the scale-related outflows, in that they offer the most flexibility regarding expenditure timing.

- Volume-related cuts are best done if service demands are also declining.

- New and unexpected needs are golden opportunities to revisit the organization's priorities, which is a reason that selective budget cuts may be appropriate as an organizational response.

- “Defending the remaining financial reserves may be more important than defending the budget” – so keep these intact to protect against future totally unexpected and urgent needs whenever possible.23

- If your organization is already very lean, and few if any cutbacks are possible without causing service provision cutbacks, rely more on a larger instant reserves level and less on reduced outflows for meeting unexpected needs.

- At times reductions or deferrals in annual campaigns or deferred giving campaigns may be necessary, but recognize the effect on this on your donors and their perceptions, including the loss of additional opportunities to solidify your organization's value proposition in their minds.

- Liquidation of assets. Temporary suspension of the use of property or eventual sale of property, facilities and plant, equipment, and land.

- Recognize that there is a great deal of uncertainty here if assets are sold off, both with respect to amount and length of time to consummate the disposal.

- This requires an estimate of “liquidation value.” What amount would you realize if you had to sell the assets quickly?

- It is best to identify in advance which operations are least “mission-central” and which would have the smallest effect on the organization's revenue stream.

Even more valuable, once you have completed Exhibit 9.8, is to do a second inventory of funding resources based on a projection of what you think they are likely to be a year from now. Especially important in that second inventory is the anticipated change in instant reserves: If an erosion in instant reserves is anticipated, take action now to tap negotiable reserves and/or a reduction planned outflows in order to restore your instant reserves. Remember that your primary financial objective as a nonprofit is to maintain your target liquidity level.

(ii) Other Financial Goals and the Organization's Life Cycle. If yours is a commercial nonprofit (can price its services to more than cover costs), you may also adopt some profitability goals for some of your lines of business. Or your organization may be at the point in its life cycle to start or build your endowment fund. For example, the University of North Florida planned a new student union (cost: $30 to $35 million) but is also building its endowment to $100 million by a certain point in time in order to (1) increase operations funding with a more predictable annual income, (2) improve its standing in the academic community, and (3) decrease its dependence on the state legislature's funding allocations.24 Stevens notes that different stages in your organization's life cycle may occasion different financial priorities; we quote here only the ones that are part of your financial planning objectives.25

| STAGE IN LIFE CYCLE | FINANCIAL CHALLENGE |

| Idea Stage | Obtain funding or financing |

| Start-Up Stage |

Create a breakeven budget Manage cash flow |

| Growth Stage |

Diversify program revenues Obtain line of credit or working capital loan Recognize that each program has different costs; some will produce surpluses, some will not Thoroughly understand and budget administrative costs Budget depreciation as an operating expense Set aside cash surpluses for working capital reserves |

| Maturity Stage |

Develop net asset (equity) balances Create operating reserves from unrestricted income Continue to develop working capital reserves to internally finance cash flow and growth Set up “repair and replacement” reserves, funded by depreciation allowances Possibly develop an endowment, take on a mortgage, or consider other forms of permanent capital |

| Decline Stage |

Use reserves only for regenerating activities, not for deficit spending Examine the budget for top-heavy administrative expenses |

| Turnaround Stage |

Create a financial plan to pay off creditors and restore organizational credibility Consider and obtain a debt reconsolidation loan to allow you to focus on the future while responsibly handling past debts Cut back to minimal expense levels Train on new mindset: “Just because it's in the budget doesn't mean there's cash available” |

| Terminal Stage | Establish an orderly way to go out of business |

Smaller organizations, especially those with $1 million in annual revenues and support or less, will find this life-cycle framework valuable for prioritizing their financial strategies and long-term financial plans. A key concern that we have not yet addressed, however, is how fast our organization can grow.

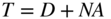

(h) BASED ON OUR FINANCIAL POLICIES AND STRUCTURE, HOW FAST CAN WE GROW? If you make some simplifying assumptions, you can determine the approximate rate of growth of activity for your nonprofit organization. This framework works much better for a commercial nonprofit (in which revenues tend to bear a direct, causal link to asset investment) than for a donative nonprofit, but it will give insight in either case. The nonprofit version of this “sustainable growth model” was developed by Marc Jegers.26 We base our presentation on his model, beginning with the data inputs needed to estimate the maximum growth rate in service provision. Your organization's maximum rate of growth in service provision jointly depends on its profitability (degree to which revenues more than cover expenses), capital structure (relative use of debt financing), and efficiency. There are two sets of inputs: operating variables and financing variables.

(i) Operating Variables. The operating variables in this model are the year-beginning and year-ending service levels, the growth rate of that service provision, the efficiency of service delivery, and profitability relative to asset investment.

- Level of service provision at the beginning of the year, X0.

- Level of service provision at the end of the year, X1.

- Growth rate in service provision, g = (X1 − X0)/X0.

The efficiency (labeled as α) with which the organization “produces” X, relative to total assets, which we represent as T: α = X/T, and the change in α (labeled as  ) is:

) is:

The profitability of the organization, or the change in net assets, is represented by P. Your organization might normally refer to this as your surplus. P would be equal to total revenues (whether restricted or unrestricted, whether gathered through fees, dues, donations, grants, or sales) less total expenses. Express this profit in relation to total assets (with the ratio labeled as m):

(ii) Financing Variables. On the statement of financial position (SFP) every dollar of assets must be financed by either debt (borrowed money, liabilities) or net assets. Therefore, we have the SFP identity:

The capital structure is the relative use of net assets (what some call equity or used to call fund balance) and debt in financing assets, with d being the ratio of debt to net assets:

For consecutive years, just include the year as the subscript:

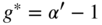

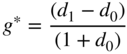

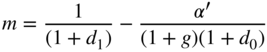

(iii) Projection Model. What we wish to determine is g*, the maximum growth rate in service provision. If you calculate this model using your year-end numerical values, it will tell you the ability to grow your service levels for the upcoming year. (For example, if you do it at the end of 2022, you will see what your maximum growth rate is projected to be for 2023.) You will have to specify, as an input to the model, how your relative use of debt financing will change during the year (d1) compared to the beginning-of-year (which is, of course, the end of the last year) relative use of debt financing (d0). The model calculates the maximum growth rate of service provision to be:

Your growth rate is limited by the use of debt financing for this year and next year (d0 and d1), the relative efficiency from this year to next year ( = α1/α0), and the “return on assets” (m).

= α1/α0), and the “return on assets” (m).

For example, let's say that our charity has a 0.50 debt-to-net-assets ratio that will not change during the upcoming year; its ratio of service provision to total assets is 0.70 and is expected to increase to 0.75; and its ratio of profit (or surplus) to total assets is 0.05. The maximum growth rate of service provision for the upcoming year is:

(iv) Interpretation. The level of service provision for our charity can grow during the upcoming year at a maximum rate of 15.83 percent unless one or more of these events occur: (1) it uses more debt for each dollar of net assets; (2) it increases its efficiency more than the 7.143 percent increase in efficiency already projected (which was based on increasing X/T from a 70 to 75 percent ratio); or (3) it increases its “profit” (change in net assets) as a percent of assets.

(v) Special cases. Three special cases allow you to simplify this formula:

Case 1: Capital structure and efficiency do not change. In this case, the formula simplifies to show the effect of financing growth strictly through profits and just enough additional debt to keep the D/NA ratio unchanged:

Case 2: Capital structure does not change and there are no profits (m = 0). In this case, the formula simplifies to show the effect of a change in efficiency on growth:

Here the growth rate simplifies to being the rate of growth in efficiency.

Case 3: Efficiency does not change and there are no profits (m = 0). In this case, the formula simplifies to show the effect of a change in the capital structure on growth:

(vi) Minimum required profitability. A very helpful planning formula can be developed from the sustainable growth model. For starters, we know the growth rate in service provision that we desire. We project our anticipated capital structure and efficiency level. The question is: What rate of profit (as a percent of assets) must we generate in order to grow at our desired growth rate? We can solve for that profit ratio with this formula:

(vii) Cautions. We offer four cautions as you apply this sustainable growth model:

- If you use revenues as your measure of service provision, make sure to subtract any “in-kind gifts,” because these will distort the revenue to assets relationship for planning purposes.

- Because of the permanently restricted nature of endowments, we recommend that you subtract any endowment-related amounts from revenues, expenses, assets, and net assets.

- Because of the long-term restrictions on most trusts, either modify your trust- related revenues, expenses, assets, liabilities, and net assets, or subtract any trust-related amounts from these accounts.

- Related to point 3, a messy issue for nonprofits is the degree to which revenues and net assets are restricted versus unrestricted. Particularly, to what degree your organization's gifts restricted versus unrestricted, and what are the revenue implications of this?

If these amounts are insignificant for your organization, you may ignore them in your growth calculations. If any of them are significant, you may either modify your numbers as recommended or ignore these issues but consider the sustainable growth rate as only a very rough approximation of the true sustainable growth rate.