CHAPTER 13

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

- 13.1 INTRODUCTION

- 13.2 HOW MUCH TECHNOLOGY AND WHICH TO CHOOSE?

- 13.3 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

- 13.4 INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IN TODAY’S NONPROFITS

- 13.5 WHAT SHOULD I KNOW/DO BEFORE INVESTING IN TECHNOLOGY TOOLS?

- 13.6 SOFTWARE: DESIGN INTERNALLY OR PURCHASE?

- 13.7 DISCLOSURE, THE LAW, AND SECURITY

- 13.8 NEEDS ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS

- 13.9 POLICIES AND PRACTICES IN KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

- APPENDIX 13A: GLOSSARY OF BASIC TECHNICAL TERMS

- APPENDIX 13B: FRAMEWORK FOR AN IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY

- APPENDIX 13C: CASE STUDY: USING TECHNOLOGY TO IMPROVE CASH AND TREASURY MANAGEMENT

13.1 INTRODUCTION

Chief financial officers in the business sector are convinced they should be more involved with the financial and operational data they have available: “Improving reporting analysis functions … is a top improvement goal. … More than 70 percent of over 380 finance executives polled [by consulting firm Kaufman Hall] say supporting decision-making is their number-one goal for 2017, a divergence from the more traditional finance and accounting roles. Over 90 percent say they need to do more with the financial and operations data at hand to help top management make critical decisions.”1 That ability depends heavily on the information technology, both hardware and software, available to them. Andy Bryant, chief financial officer (CFO) of Intel, leads Intel's human resources, information technology (IT), and procurement, and is heavily involved in strategic decision making. He sees this expansive role as the trend for the future in businesses. For many nonprofit CFOs, such a multifaceted role is normal, not exceptional. Additionally, Bryant believes that Intel's IT is better managed now that it is under finance, and he thinks the finance office acts more appropriately toward the IT staff due to having the reporting relationship.2 According to survey data from NTEN: The Nonprofit Technology Network, the IT area is housed within the finance department in about 15 out of 259 surveyed nonprofits (see Exhibit 13.1). The most commonly seen organizational structure for the nonprofit IT function is to have it set up as a separate IT department, a relatively recent development.

Source: Robert Hulshof-Schmidt, “NTEN: The Tenth Annual Nonprofit Technology Network Nonprofit Technology Staffing and Investments Report,” May 2017. Used by permission.

Exhibit 13.1 Organizational Structure of IT in Nonprofits

Information technology has been the buzzword for the past three decades. The rush to automate and implement new technologies and better harness data for improved performance and greater effectiveness has yet to slow down. Technology has been seen as the solution to increase productivity, reduce errors, keep up with the increasing demands for more and more information, and improve performance. Information technology is “concerned with all aspects of managing and processing information,”3 and may be defined as “… the use of hardware, software, services, and supporting infrastructure to manage and deliver information using voice, data, and video.”4 Consider how the Information Technology Department of the State of North Dakota frames IT and the budget implications for its agencies (see Exhibit 13.2).

The top priorities as we enter and move through the third decade in the new millennium are answering questions such as the following:5

- Do you have the right technology to help you manage multiple revenue sources?

- Do you have technology to help mitigate fraud?

- Do you have technology to help make the audit process run more smoothly?

Nonprofit board members list cybersecurity (protecting against the criminal or unauthorized use of electronic data; 18 percent) and changing technology (17 percent) as two of their top seven concerns.6 Your technology acquisition, maintenance, and funding plan will likely be of major interest to your board.

Source: Adapted from listing at http://www.nd.gov/. Used by permission.

Exhibit 13.2 Information Technology Explanation and Examples

Finance staff is in a key role in regard to IT spending, both because IT spending is largely made at management's discretion and because of the large financial impact of IT expenditures. Notes Michael Blake, a financial officer at nonprofit healthcare services firm Kaiser Permanente, “Finance has to play both an oversight and a consultative role, and play them both well … finance has to be discerning about budget decisions or risk thwarting strategic growth [such as ordering an across-the-board reduction in IT expenses].”7 About 3 in 10 corporate CFOs believe the IT area should report to the finance area, about 6 in 10 believe IT should not report to finance but that they should work closely together, and the remainder are evenly split on having them collaborate only on matters of spending or work entirely independent of each other.8 Finance staff should push for adequate technology to assist it in its critical role as risk management captain – with proper data, overall risk exposure to all the different risks the organization faces may be assessed, monitored, and managed.9 (See Chapter 14 for coverage of risk management and Appendix 14A for coverage of derivatives.)

To properly evaluate the need for technology tools and how to implement them, it is necessary to explore what each can offer and attempt to forecast the future capabilities, direction, and growth of each industry. These tools improve and expand rapidly. They are out of date the moment the purchase order is issued; however, finding some stability in this arena is both possible and necessary before their introduction into the workplace.

When many people hear the term “information technology,” the computer is the first tool that comes to mind; however, technology tools have been with us in the workplace since the first abacus was introduced to accounting. The migration to advanced technology tools – personal computers (PCs) that can do just about anything one might wish to do on a computer, tablets, mobile applications, networks, banking and purchasing over the Internet, electronic payments and donation collections (including those made from payors' or donors' digital wallets), e-mail with documents attached, voice mail, and so forth – has been thought to alter radically how we work, when actually it has simply improved on what is familiar by repackaging these tasks and workflow to be smarter, faster, and more efficient.

13.2 HOW MUCH TECHNOLOGY AND WHICH TO CHOOSE?

IT tools can dramatically improve performance if they are used appropriately and wisely. They can also be used inappropriately and damage a smooth-running operation. For example, many companies are opting for the use of electronic receptionists, offering their customers a series of questions to direct their calls. This technology can be very useful in the right environment, such as a highly technical customer base; however, if the customer base is nontechnical (more service based) or if the service is not highly dependable, the selection of this technology may damage customer or client relations.

The same is also true with the use of computers, whether tablets, laptops, or desktop PCs. There should be a good, sound reason to automate a task or process, not just a desire to jump on the technology bandwagon. To analyze your organization's need for automation using technology, use the checklist in Exhibit 13.3.

Exhibit 13.3 Technology Checklist

(a) WHAT TYPES OF TECHNOLOGY TOOLS SHOULD I CONSIDER? Before deciding on a specific platform (e.g., PCs or Macs), six questions should be answered:

- What software is available for this system that the business will require? Traditionally, Macs have been used in businesses that produce graphics (e.g., advertising, marketing) and PCs have been used for number crunching (e.g., accounting, forecasting). While the differences between the two platforms are diminishing rapidly, the majority of accounting applications, for example, are available only for the PC, and some design packages are available only on Macs.

- Who will need to access the information? Will a network need to be established linking the computers? If so, there may be a need to standardize around a certain type of architecture and possibly compromise on the financial management needs with that of the rest of the business. If not, a diversity of platforms will not hinder or interfere with your specific needs in the financial management arena. It is also possible to establish two different networks – one for the administrative/business needs of the organization and one for the creative aspects. System compatibility continues to improve, making this less of a concern than it was formerly. There are still issues connecting financial/accounting software with fundraising/donor management software when they come from different vendors.

- Are there sufficient resources (financial and staff) to implement a new technology? It is easy to budget the costs of the equipment, but the less obvious costs of down time, training, installation, maintenance, new supplies, and other factors are not as easy to predict, manage, or forecast.

- What does the research of others in a similar industry suggest? With noncompeting organizations, it is often possible to develop strategic alliances to share expertise and reduce development costs and the risks associated with the implementation of new technologies. Also, TechSoup (http://www.techsoup.org/nonprofitsoftwaresem) and Good360 (www.good360.org) have been valuable sources of free or inexpensive computers, printers, and software (in Good360's case, for 57,000 prequalified nonprofits). Furthermore, Microsoft Office 365 is available to nonprofits for a donation (single user) or small fee (e.g., $10 per user per month) for the full-featured version.

- Is there a suitable software product available on the market, or will a customized product be required to meet the need? Operating system and equipment advancements occur almost annually. If a nonstandard software or hardware is selected, these systems will become obsolete (nonupgradable) almost immediately. Most organizations learned this lesson too late and are faced with the task of reintroducing automation. To avoid this obsolescence, an off-the-shelf package, moderately customized to meet the organization's needs, should be selected by most small and midsized organizations. Selecting the appropriate software package should be done carefully and after checking with staff at organizations similar to your own.

- Have the findings and decisions been reviewed carefully? All decisions, assumptions, and recommendations should be discussed with peers. If possible, a consultant with expertise in this specific area should be contracted to review the plans.

All but the very smallest organizations will also require a computer network to allow data and possibly software sharing. If yours is one of the many one-person nonprofit organizations, you should consider the need for a network as you begin to make plans for onsite volunteers and additional staff. The key items to consider in designing and purchasing your network are:

- Know what you need and what you don't need – get input from staff.

- Consider new functionalities that are available, such as remote access via the Internet to your network (for telecommuters and staff as they travel) and cloud-based applications. Determine responsibilities for various aspects of the new equipment and software (and consider whether having extra features available for in-house use is cost-effective).

- Obtain multiple bids.

- Get referrals from trusted sources, possibly utilizing a freelance technology expert to help with your decision making.9

(b) ARE THEY REQUIRED? If a task or process can be effectively performed manually, technology tools may not be required; however, the ability to communicate with or pass data to other businesses or individuals may require automation or the introduction of technologies.

If there is a need to communicate and share information with other organizations, businesses, government agencies, bureaus, or the like, technologies should be introduced that will enable compliance with these demands. Implementation strategies should include the immediate need(s) as well as long-term strategies for applying new technology in other areas of the organization.

(c) DO I NEED THEM? In a nonprofit organization, technology may not be required for all applications. In the financial arena, however, the capabilities provided by new technologies will dramatically improve the quality of work or at least streamline or simplify the process. The migration from “counting beans” to “analyzing trends and forecasting needs” is the major thrust of automating the process of financial management.

The major focus of financial management is the ability to: review financial information to make decisions; forecast needs, especially cash requirements and the resulting cash position; evaluate performance; and assess progress. The quality of financial management is based on the integrity and timeliness of the information reviewed and evaluated. The manual process of accounting has provided a level of accuracy and quality that for many years was acceptable. The introduction of technology and the automation of the process provide a higher quality of data than can be provided by a manual accounting process. The removal of as much human error as possible from the process is the single most important reason to automate.

(d) WHAT WILL THEY DO FOR ME? Many financial software programs on the market resemble easy-to-use checkbooks. While some organization's financial management needs may be much more sophisticated, one of these programs can provide all that is needed to automate the financial operation of many businesses. These software programs, if set up properly, will enable individuals to enter information in a format and style that is easy to understand and use. The ability to produce reports and retrieve information from these systems is quite remarkable. With most of these off-the-shelf programs, a balance sheet can be produced as swiftly and easily as a transaction record.

(e) WHAT WILL THEY NOT DO FOR ME? Technology cannot solve the organization's problems that are caused by human resources conflicts, poor organizational structure, or complex or ineffective policies or procedures. In fact, the introduction of technology will bring these problems to the surface and, in many cases, magnify their impacts on the organization. It is not uncommon, when technology implementations are under way, for the technology to be blamed for crippling the organization, when in fact the organization was already crippled by these other factors.

It is important to remember that technology tools automate a predefined task or process. Technology does not define the process. If there are existing problems with the processes, there will be problems in the automation of the process.

(f) CAN I AFFORD THEM? Software and hardware technologies can be expensive. The initial costs of the equipment and software are only the beginning of the expenditure requirements. With any decision to purchase, there must be a justification for the expenditure. Exhibit 13.4 illustrates one method of determining if there is a justification for the introduction of a new technology.

| One-time costs: | ||

| Typical PC configuration | $1,250 | |

| Software | 750 | |

| Printer | 250 | |

| Other | 250 | |

| Total setup costs | 2,500 | |

| Annual costs (recurring): | ||

| Training | 500 | |

| Supplies | 300 | |

| Maintenance | 200 | |

| Total Annual Costs | 1,000 | |

| $3,500 | ||

| Average | Productivity | |

| Annual | Increases | Annual |

| Staff | (% of Positions | Net |

| Salary | Eliminated) | Savings |

| $35,000 | 5% | $1,750 |

| $35,000 | 10% | $3,500 |

| $35,000 | 15% | $5,250 |

| $35,000 | 20% | $7,000 |

| $35,000 | 25% | $8,750 |

| $35,000 | 30% | $10,500 |

| $35,000 | 35% | $12,250 |

Exhibit 13.4 Determination of Expenditure Need

Exhibit 13.4 assumes the cost of a typical PC configuration at $3,500. At Line 2 of the data in the bottom panel, a 10 percent increase in productivity (or elimination of an extra position at that percentage) recovers the costs of the typical configuration in the first year. Each subsequent year, a savings of $2,500 ($3,500–$1,000) can be achieved.

The chart ends at 35 percent. However, if one staff person or the need to hire an additional staff member can be eliminated, the costs of the technology are assuredly justifiable.

(g) WHAT CHANGES WILL THEY INTRODUCE TO MY ORGANIZATION? All change is dramatic to an organization. Managing the change is the only way to assure that the introduction of new technologies will provide a desired and positive outcome. Accepting that all change is challenging, the introduction of technology has its own set of change issues and concerns. Many of these issues and concerns are unfounded and are based on myths about technology, but they still need to be addressed and discussed.

Assimilating the new technology will not be automatic. Depending on the level of change, new workflows, diagrams, work rules, policies, and procedures will need to be reviewed and, in most cases, revised or rewritten. Putting a computer on someone's desk will not automatically provide increases in productivity. In most cases, the transition process will yield a decrease in productivity until the training and assimilation process is complete. All support systems and processes need to be reviewed, and your staff members need to be retrained.

(i) Example 1: Slow Integration. In one organization, the use of the computer was widely accepted, and staff learned quickly how to enter the information into the system. Reports were produced, data appeared to be of higher quality, and the staff should have had more time for analysis; however, the support structure for the system had not been redesigned. Staff members were still maintaining all of the paper documents in cross-filed indexes and logs, as they always had. They had learned to provide others with the information they needed but had not yet learned how to use the information themselves, nor did they believe it was their place to make major changes in the way they maintained their records.

(ii) Example 2: Flawed Integration. In another organization, a request was made of one staff member to provide historical information about spending on an item type. The staff member went immediately to her paper files rather than the computer. When questioned about it later, she stated that the individual wanted a specific item rather than information on one of the categories of expenditures. When reminded that this person bought only that item, so that item matched up one-to-one to a single category, she realized she could have retrieved the information from the computer system.

In many other implementation situations, the biggest problem is the dramatic cultural change regarding what is valued in the organization. Rules and regulations that had taken decades to learn and memorize were suddenly programmed into the system. Individuals who had spent so much time learning these rules were suddenly no more qualified or valued than the newest person in the organization. So, in addition to new workflows, ways of positively rewarding and recognizing tenure need to be established in the organization.

Another challenge to the introduction of technology is fear: fear of a machine, fear of losing one's job, fear of not being able to use the software or other technology. The greatest pacifier is open communication.

To introduce technology into an organization:

- Determine what impacts the new technology will have on the organization.

- Develop a strategy for communicating the plan and the change to the staff within the organization.

(Also refer to Appendix 13B for guidance on your implementation strategy.)

The strategy should include:

- Why and how the need for technology was determined

- Management's commitment to the change

- How the technology will be introduced, who will be affected, what it will do

- How training will be handled

- The timeline (schedule) for the implementation

- The support systems that will be available

- How future communication about this change will be administered

- How this technology will be applied within the organization, what manual process or previous technology it will replace, what policies or procedures will be altered, and so forth

13.3 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

(a) HOW CRITICAL IS DATA? “Bad data, bad decisions.” Many nonprofits make poor decisions because they do not have the information available, do not know how to process or analyze the information, or do not have the time to carefully consider the decision alternatives and the information related to each of those alternatives. Furthermore, our Lilly study documented that the use of IT (particularly PC technology) was closely correlated with the proficiency of the organization's overall financial management. Using the information processing power of the basic financial spreadsheet, in particular, is essential to your organization's financial decision making. Facing complex environments and scarce resources, nonprofits must manage the knowledge resource effectively and efficiently.

(b) KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT. Many nonprofits use knowledge intensively – a prime example is philanthropic foundations. Identifying cutting-edge grantees or grant ideas, evaluating grant proposals, processing grant progress reports, and publishing policy reports are all knowledge-based activities. However, if these organizations do not invest in the proper systems, people, and organizational infrastructure, they will be hampered in their efforts. One foundation, the Casey Foundation, went to the extent of having a team classify everything the foundation had ever learned from the studies it had funded, so this knowledge could be accessed quickly and efficiently.10

One of the most exciting prospects for your organization is to begin to teach (or enable the learning of for) your employees and volunteers, as well as your board, the linkages between your organization's activities and its hoped-for outcomes. Researcher Natalie Buckminster11 argues that this activity-outcome instruction is a tremendous way to promote organization learning; we concur.

(i) Is Yours a Learning Organization? Peter Senge, probably the leading world expert on organizational learning, defines a learning organization as one in which “people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together.”12 How are your staff members' capacities being expanded? Do those with innovative ideas, or who challenge the conventional wisdom, get their ideas dismissed abruptly or shot down by the leaders? Do leaders help team members “see the big picture”? In particular, effective businesses have a “value culture,” in which all employees are guided toward the likely effects of their activities and decisions on the company's stock price, or value. In nonprofits, the effect of activities and decisions on mission attainment and the value propositions for clients and donors and other funders are key, but so too is the likely effect on the liquidity position of the organization. Constant training, mostly done informally in “teachable moments,” helps your employees see the connection of their tasks to cash inflow and outflow timing, amount, and risk. Working to model the type of culture you wish to create is essential, as noted by Gard Meserve, chief information officer (CIO) of Clarkson University.13

(ii) Steps Toward Building a Learning Culture. Senge identified five disciplines that must be harnessed for your organization to become a learning organization:

- Systems thinking: Look at your organization as a whole, including how it fits into its environment, and recognize how all of its parts work together and not independently.

- Personal mastery: There is no way your organization can be a learning organization if individuals are not learning individuals.

- Mental models: Understand or picture how the world works in some specific arena.

- Development of a shared vision: How will the world be different if our organization succeeds in achieving its mission?

- Team learning: Team members must learn to exchange ideas, which necessitates suspending assumptions and regarding others as colleagues, and stimulating this dialogue often requires a facilitator to help the process.14

(iii) Managing Intellectual Capital. The more knowledge-based your organization (think educational institution), the more important it is to recruit, select, retain, and tap into your human resources. Beyond that, shepherding great ideas and processes, learning from successes as well as failures, learning from others in similar organizations, protecting unique ideas from theft or piracy, and maintaining a usable “knowledge database” are all key features to effective management of intellectual capital.15

13.4 INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IN TODAY'S NONPROFITS

(a) ELECTRONIC COMMERCE. Electronic commerce, or e-commerce, is the electronic exchange of information and/or payment flows. It could be between organizations or involve individuals. Some label this process as “e-business,” not e-commerce.16

(i) Doing Business Electronically. There are many functions that your organization may carry out electronically. Doing business electronically offers the possibility of doing things faster, with less human involvement, and more accurately. We shall expand on specific processes and functions later in the chapter.

(ii) Your Organization's Website. A key component of your IT is your organization's website. Potential board members, employees, volunteers, clients, and donors and other funders all gather information and build an image of your organization from your website. This is also a perfect spot to post annual reports and annual financial statements. Fundraising potential through your website is high, too; we return to this topic in a later section.

(b) SPREADSHEETS AND BEYOND FOR DATA AND DECISIONS.

(i) Spreadsheets. Flexible, easy to use, and yet prone to error – this is the way most users view spreadsheets. Almost all businesses and nonprofits find some use for spreadsheets, including their function as a basic database. Because of the almost universal access of Microsoft Excel, it is easy to share data with other staff as well as with your stakeholders using a spreadsheet.

(ii) Data Warehouse. A data warehouse is “a collection of data gathered and organized so that it can easily be analyzed, extracted, synthesized, and otherwise used for purposes of further understanding the data.”17 This warehouse is created by indexing transactions data and setting up a table of contents, chapters, and then paragraphs. Make it available to others in your organization, with password protection, and place it on your network.18

(iii) Bank/Financial Service Provider Online Services. We most often think of bank portals or other websites when we consider online services. These are extremely useful for looking up account balances, seeing if items have cleared, finding out if electronic transactions were executed, and viewing the front and back of images of checks that were presented to see if there might be fraudulent activity. However, larger organizations are now moving to the next generation of services, consistent with the outsourcing issue we covered earlier. For example, consider the possibility of outsourcing your disbursements using a form of EDI. “EDI” refers to electronic data interchange, which involves “the electronic transfer of information or data between trading partners and to communications between the company and its bank.”19 An example of a bank's comprehensive disbursements system and how it links to your organization and your payment file is presented in Exhibit 13.5. You may wish to refer to Chapter 11 for greater detail on automated clearinghouses (ACH), wire, and check payment methods.

Source: Comerica Bank. (https://www.comerica.com/business/treasury-management/payables/integrated-payables.html). Used by permission.

Exhibit 13.5 Outsourced Disbursements

The most recent survey of banks' commercial payments capabilities finds:20

- Almost all banks offer paper checks, wires, and debit cards;

- Sixty-one percent offer web-based cash management solutions and credit cards;

- More than 54 percent of respondents indicate that their bank offers same day ACH origination; yet

- Only a small minority of institutions offer mobile B2B (business-to-business) and B2P (business-to-person) payments capabilities.

(iv) Application Service Provider. Rather than purchase software, why not “rent” software that is hosted on the vendor's website? This is the idea behind application service provider offerings. For example, SunGard offers its AvantGard application service provider (ASP), which is oriented to businesses with between $250 million and $1 billion in sales. Selkirk Financial Technologies, Inc., has a web-based service (Treasury Anywhere) that it sells through banks.21 We believe that in the near future these platforms will migrate to smaller businesses and to small-to-midsize nonprofits.

(v) Treasury Workstation or Treasury Management System. For midsize and large organizations, there is treasury workstation (TWS) or Treasury Management System (TMS) software. Most large businesses use TWS or TMS software to assist in the treasury function. There are now PC-based systems that may work for midsize or smaller organizations. These enable the user to get detail on changes to cash positions and initiate multibank, multicurrency operations. Add-on modules include an interface to the general ledger, a foreign exchange trading module, and an investment and debt management module.22 Businesses report that the implementation of a treasury workstation software solution takes between 6 and 11 months, with those having less than $250 million in revenues averaging over 8 months.23 You should consider the pros and cons of a TWS or TMS software investment. Fully 31 percent of businesses are not convinced that the benefits of such a system are worth the cost.24 One in three companies indicate they still use Microsoft Excel for their treasury-related tasks. A major concern is the less-than-acceptable TWS or TMS forecasting module, which users deem as “not working properly” or “ineffective.”25 Offsetting advantages of using a TMS include (1) auto-updates to the forecast based on actual data brought into the system each month, (2) integration of bank statement activity, (3) 90%-plus cash visibility on a daily basis coupled with much-simpler and perhaps automated integration of forecast data from ERP systems, financial planning and analysis systems, or internal data warehouses, and (4) inclusion of investment, debt, and currency derivative flows – both principal and interest payments – automatically incorporated in the forecast.26

Now for a little help with the jargon. The development of treasury software has generally proceeded from treasury workstations (TWS) to Treasury Management Systems (TMS) to Treasury and Risk Management (TRM) cloud-based platforms. The distinctions are not as clear as we draw here, but generally TWS was software loaded on the desktop PC that tracked cash and investments transactions (and available only to the person(s) using that desktop PC), TMS uses client server technology and focuses more on cash management and helps automate the treasury operation (and is available, potentially, to anyone in the organization), and TRM enables one to manage both cash and risk for the entire organization and can be used by all organization units and be connected to the organization's banks and other third-party systems. The software vendor hosts the TRM software “in the cloud,” meaning you no longer absorb the cost and spend time trying to maintain the TWS or TMS software, interfaces, security, and software updates nor the hardware on which these are loaded.27 Because these terms are not universally used in the way we have presented them, you will still need to clarify with your vendors what the potential software does and how it is made available to your organization. Some in the field use the descriptor TMS to refer to all treasury-related software, including TWS software.

(vi) Enterprise Resource Planning System. Here is a good definition of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems: “… the systems and software packages used by organizations to manage day-to-day business activities, such as accounting, procurement, project management and manufacturing. ERP systems tie together and define a plethora of business processes and enable the flow of data between them. By collecting an organization's shared transactional data from multiple sources, ERP systems eliminate data duplication and provide data integrity with a “single source of truth.”28 As noted earlier, there is a trend toward hosted ERP systems following the ASP model of software delivery or “pay per user” web-based multiuser offerings known as “Software as a Service” (SaaS), which allows multiple users via one website and usually has been developed as an Internet software application.29 Cloud-based ERP software, in which the Internet is used to store and access files, is now available and experiencing rapid growth in use. Two large vendors are Oracle and NetSuite. Cloud-based ERP systems are much less expensive compared to the cost when “legacy” ERP systems were first introduced, so cloud-based “SaaS” ERP systems should be considered by some small and all midsize as well as large nonprofits.30

(c) DEDICATED SOFTWARE. Consider single-purpose software as another option in your IT toolbox. We will briefly discuss five forms of this: dashboards, fundraising, purchasing/e-billing/e-payment, budgeting and planning, and human resource management.

(i) Dashboards. A dashboard is a single interface that gives your management access to “key performance indicators,” which are action-oriented measures that help monitor and trigger corrective actions.31 Your balanced scorecard may have a number of metrics that are monitored via your dashboard, for example. Dashboard design includes these steps, according to Daryl Orts, now executive vice-president of Magnitude Software:

- Refine the user interface and control flow.

- Confirm the data sources for each data element.

- Determine how to “persist” data when historical trending information is desired but unavailable from the transaction database.

- Define the queries needed to retrieve each data element.

- Determine drill paths.32

Nonprofits are now finding dashboard functionality in ERP systems as well.33

(ii) Fundraising Software. Software from vendors such as Blackbaud (Raiser's Edge)34 are popular applications in the nonprofit world. What excites most nonprofits, though, is the potential to raise funds via their website. Consider these survey statistics:

- A majority (58 percent) of donor participants reported they use the Internet to search for information, volunteer, donate, and sign petitions for causes or organizations they want to support.

- Three out of four [donor] respondents take some additional action – on-line or off-line – after visiting a charity-oriented website. Some 60 percent stated that had they not visited the charity site, they either definitely would not have taken further action or were unsure that they would have taken additional action. The nonprofits use the Internet to provide information on their missions, goals, issues, achievements, financial data, and to gather support by encouraging website visitors to become members, donate, volunteer, sign a petition, or buy a product.35

Your nonprofit will also want to tap the potential for communicating and raising funds through mobile interfaces. More and more donors are giving from their smartphones, including texting amounts to dedicated third-party numbers or clicking through on e-mails they read on their phones. E-mails are now accessed on smartphones or tablet PCs more frequently than on desktop or laptop PCs. E-mails should include a payment button that the reader can tap to donate. Nonprofits send an average of 69 e-mails annually to each e-mail list subscriber, get one donation per 2,000 e-mails sent, and receive an average of $36 in donations per 1,000 e-mails sent, according to M + R Benchmarks.36 Social media sites (Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and others) offer growth potential as your organization can accept payments through this source: in Snapchat, your donors can send digital payments to “Snapchat Friends,” and YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter have “donate now” functionality.37 Your donors may also have and use mobile wallets, by which they store credit card or debit card information in a digital form. They can then initiate donations or payments using their smartphone, tablet, or smartwatch.

(iii) Purchasing, E-Billing, and E-Payment Software. In the business sector, when companies embrace web-based applications, they experience a reduction in total financial transaction costs of as much as 40 percent compared to average firms.38 Even more impressive, companies that move from paper to electronics in payables areas, including supplier invoicing to vendor payments, experience costs reductions of up to 90 percent, according to Hackett Group research. Comparing top-quartile cost to bottom-quartile cost companies, and factoring in their sizes, this constitutes a $590,000 savings per $1 billion in sales.39

(iv) Budgeting and Planning Software. As we discuss in Chapter 8, planning and forecasting software (sometimes called business performance management software) is touted by some as offering a significant analytical advantage. This software is offered by vendors such as Hyperion (now part of Oracle Software), Adaptive Insights, Centage, Prophix, and PowerPlan.40 Red Cross, Feeding America, and other nonprofits use this software to automate and streamline processes and tasks such as budgeting, forecasting, financial reporting, financial analysis, and project planning.41 Not only does this increase the efficiency of the budgeting process, but it adds to the flexibility of the process by enabling long-term forecasting while reducing the amount of human error in the budgeting process.42 Other than financial spreadsheets, budgeting, forecasting/planning, and business intelligence software represent the primary financial (nonaccounting) software tools used by businesses.43 A Financial Planning and Analysis survey of large businesses and their budgeting processes revealed the following:

- 37 percent of CFOs and finance leaders said that their organizations' budgeting processes needed improvement.

- 25 percent said their companies' budgets quickly become obsolete.

- Only 40 percent described their current financial planning and analysis system as effective.

- 62 percent claimed their staff was too busy in basic duties to make the changes needed to keep their budgets up to date.

Perhaps most important, many companies simply do not rely on technology solutions to make the budgeting and forecasting process more efficient even with the potential to do so.44

Of course, the percentages would likely be somewhat different for nonprofits, but we are also aware that coming up with budget estimates is considered to be one of the most difficult tasks in the nonprofit finance function.

(v) Human Resource Management Software. The very first ERP software applications were focused in the area of human resource planning and management. Oracle, SAP, Microsoft, Epicor, and Incor are five of the largest vendors in the marketplace of 100+ vendors. At a minimum, consider having a human resource information system (HRIS) to keep track of your workforce. Most midsized and large organizations now provide all of their benefits information and forms online, often through an employee portal. Self-service not only allows 24/7/365 access but also minimizes human resource staff forms-related request handling.

13.5 WHAT SHOULD I KNOW/DO BEFORE INVESTING IN TECHNOLOGY TOOLS?

With the introduction of any new technology, there will be changes and unexpected delays and costs; plan for them. If no other method of allowing for hidden expenditures is possible, an extra line item should be added to the budget for “Unforeseen Expenditures” as a percentage of the total budget.

If a vendor or a contractor promises to deliver a product by a certain date, rewards or penalties for meeting or missing the deadline should be included in the contract.

In addition:

- Budget time for planning the implementation as well as for needed staff training.

- Recognize that not all staff members will agree with the decisions, and some will try to stop or sabotage the implementation, either directly or indirectly.

- Accept that some staff members may not be able to deal with the changes and may leave on their own, or they may need to be removed from the organization or retrained for other positions.

- Seek advice from colleagues and peers from other organizations. Pay careful attention to their experiences, and assume that any problems or obstacles they faced will occur in your organization, no matter how well the implementation plans and strategies are carried out.

- Realize that mistakes will be made along the way.

(a) PLANNING FOR GROWTH. The biggest challenge of any new venture is predicting future needs. With technology, this predicting activity can be especially critical. Many technologies are sold in blocks, accommodating a specific number of users, telephones, connections, and the like. While it is never wise to overpurchase, it is also imprudent to replace existing equipment unnecessarily or too quickly.

Predicting future growth does not have to be limited to arbitrary guesswork; however, an accurate prediction of future needs should not be expected. Projections should be conservative, either in terms of growth or investment. The best measurements begin with an analysis of historical growth, plus or minus contributing factors.

Exhibit 13.6 lists the total number of employees for a given organization over a previous 10-year period, with an average of 61 employees. Predicting that the organization will have an average of 61 employees per year would be a misinterpretation of the data. Examining the data more closely shows that a greater pattern of growth occurred during the first five years, with a steady but slower growth in the second five years.

| No. of Employees | |

| 2009 | 15 |

| 2010 | 30 |

| 2011 | 45 |

| 2012 | 47 |

| 2013 | 49 |

| 2014 | 55 |

| 2015 | 89 |

| 2016 | 92 |

| 2017 | 92 |

| 2018 | 97 |

| Average: | 61 |

Exhibit 13.6 Growth Analysis Using Historical Figures

Microsoft Excel includes a handy built-in formula for calculating the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of a data series. This function, RATE, uses this format for our entire 10 years of observations (9 years of growth):

The first item is the number of years of growth, which is nine in our example. The second number is the payment per period, which is 0 in our example. (As an aside, if you also use this function for a loan payment, enter the payment per period.) The third number is the starting value, or “present value” in the series, which is $15 in our case. (You must put a negative sign in front of it.) The fourth number, 97, is the ending value, or future value. The following 0 indicates that the employee numbers are at the end of the respective periods. The 10 is a starting guess for the percent growth rate – if you don't have any idea, 10 is a good number to use.

Excel gives us a result of 23.05 percent for the entire period. However, just as your visual examination of the data suggested, when we use only the first five years or only the last five years (each of which spans four years of growth) in the growth calculation, we get very different growth rates:

| 2009–2013 | 34.44% |

| 2014–2018 | 15.24% |

Clearly, a new trend better characterizes later years, and to the extent “nothing significant has changed” for the future, we would want to extend the data at a 15.24 percent rate of growth, not a 23.05 percent rate of growth. Watch for pattern or trend changes in your organization's revenues and costs, and capture these when doing your projections.

(b) OUTSOURCING? Outsourcing of IT comes in various forms. You may outsource your entire IT department, outsource software by using hosted software on a vendor's computer system or through the cloud, or merely outsource certain functions such as payroll processing (many organizations do the latter through ADP or Paychex). It is always a consideration in any IT-related decision that you make.45 Three “IT Service Models” are available for your consideration: in-house IT staff, hourly services, and managed services. The in-house approach is attractive due to fast response time and familiarity with your organization's workflow and process, but potentially suffers from expense, lack of training and/or oversight, and the minimal amount of redundancy. The hourly service model means you pay only for the time you need, but again might bring a limited skill set, is reactive (a system or service is broken, so call them in), and it is challenging to know how much to allocate in the budget. Managed services contracts are for a flat fee and easy to plan/budget, typically bring a strong skill set, and might proactively bring insightful (and even pro bono) consulting about new/better ways to do things. Downsides for managed services include that they might be more expensive than hourly services and the service personnel are not onsite 40 hours per week like in-house staff would be.46

13.6 SOFTWARE: DESIGN INTERNALLY OR PURCHASE?

Many software companies are now working with clients to allow them to use the software under a service contract or lease/finance software. Software as a service (SaaS) is defined as “… a software distribution model in which a third-party provider hosts applications and makes them available to customers over the Internet. SaaS is one of three main categories of cloud computing, alongside infrastructure as a service (IaaS) and platform as a service (PaaS).”47 Paying fees for SaaS or leasing software may cost more than buying but these options are often worth it in the longer term. A typical approach in many organizations who need to purchase computer technology (hardware and software) is to engage in a lengthy process of identifying needs, shopping vendors, and so forth. After identifying the needs, they prepare a request for proposal including all the specifications they want and need.

A shortcut many take is to network with other similar organizations and approach a vendor to design a system that works for everyone. The vendor maintains the right to sell the product to similar organizations. The end result is that the development costs are spread among a greater number of users.

Most nonprofits choose to purchase existing software and tweak it to meet unique needs rather than design their own software. In most cases, at least three major vendors, in any given application area, provide software for a specific task or process. It is easier, cheaper, and safer to purchase (or use for a period based on a service contract) one of these products than to design a new one. In addition, these vendors will also provide (generally free of charge) hardware specifications for the application.

Changing technology requires the technology manager to constantly review what the organization's systems do and do not do, and to modify needs based on current procedures and task flows.

13.7 DISCLOSURE, THE LAW, AND SECURITY

There are many laws regarding the disclosure of information. A public institution's financial records may be public record; however, in many instances a portion of the data does not need to be disclosed, and in some cases, disclosure of certain pieces of information is illegal. It is imperative that a thorough investigation of the laws and policies pertaining to the types of data maintained be reviewed (see Chapter 15 for additional resources on maintaining data).

(a) A COMPANY DATA POLICY. Establishing a policy regarding the use of company data will also provide a mechanism for training staff about the security requirements of the data.

Exhibit 13.7 provides a sample policy that pertains to maintaining sensitive and/or confidential information. Exhibit 13.8 provides a sample communication policy checklist, which guides you in setting policy governing the increasingly sensitive area of electronic communications, especially e-mail. While written for associations, it generalizes nicely to all nonprofits. We emphasize that this sample policy and the wording therein is not to be construed as legal advice, and you are advised to consult with legal counsel for policy wording based on current state and federal regulations and legislation. Exhibit 13.9 provides a checklist of items to include in your “Acceptable Use” policy regarding use of your organization's computers, e-mail, and Internet access. Because Internet issues are so prevalent and potentially devastating, we also provide in Exhibit 13.10 a checklist of items to include in your employee “Internet Policy.”

Exhibit 13.7 Guidelines for Using Personal Information on Individuals

Source: Victoria L. Donati and Jennifer A. Hardgrove, “The Importance of Being E-Conscious,” Association Management (June 2002): 59–63. Used by permission.

Exhibit 13.8 Sample Communications Policy Checklist

Source: Eric Gunderson, “The Importance of Acceptable Use Policies,” July 19, 2017. http://www.howardtechadvisors.com/better-together-newsletter/acceptable-use-policies/. Used by permission. Eric W. Gunderson is an attorney and partner at Farrell & Gunderson, LLC. This information is not to be construed as legal advice, and readers are urged to consult with legal counsel before finalizing this type of policy.

Exhibit 13.9 Checklist for Acceptable Use Policy for Computer, Internet, and E-Mail Use

Source: Authored by Michelle Pelszynski. Published in Jason Maeser, “Creating Internet Policies for Employees,” July 11, 2017. http://www.howardtechadvisors.com/better-together-newsletter/acceptable-use-policies/. Used by permission.

Exhibit 13.10 Checklist for Employee Internet Use Policy

(b) SECURITY ISSUES AND TRENDS. It is hard to overemphasize the importance of security for your IT area. Not only is the number of security breaches growing rapidly, but also the loss of productivity and time involved in correcting problems is a serious issue. Spyware, instant messenger, and peer-to-peer (P2P) threats, as much as 60–80 percent of incoming e-mail being spam or having viruses attached, and “phishing” attacks (e.g., phony bank inquiries that attempt to get employees to divulge sensitive personal or organizational information) are some of the trends organizations grapple with.48 Losses per company of security breaches are estimated by the companies at about $204,000. A large-scale survey finds that the top three causes of loss are (1) viruses, (2) unauthorized access, and (3) theft of proprietary data. To try to combat these attempts, businesses spend an average of about 6 percent (with a range of 1 to 13 percent) of their IT budgets for IT security and risk management, according to the Gartner Inc. IT Key Metrics Data study.49 “Best practice organizations” spend between 4 and 7 percent of the IT budget on IT security and risk management, but more important than the allocation is the organization's focus on spending for “IT operations and security that reduce the overall complexity of the IT infrastructure and work toward reducing the number of security vulnerabilities.” One of the biggest issues, in our judgment, is the ultimate effect of the privacy and data security concerns of individual donors on their online giving.

One issue requires special attention for healthcare organizations: Electronic records management. Sarbanes-Oxley legislation and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) both stipulate fines and/or prison sentences for the mishandling of certain kinds of records.50 HIPAA also requires that healthcare organizations maintain customer information for six years. E-security and retention are consequently vitally important for healthcare organizations.

13.8 NEEDS ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS

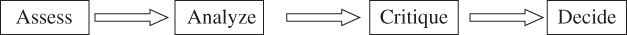

Before deciding on the type of technology, needs and requirements must be determined. The tool the experts use for seeking out this information is a needs assessment. There are as many ways to conduct a needs assessment as there are technologies from which to choose. After completion of the assessment, an analysis of the information is performed to evaluate the results. The steps involved in conducting a needs assessment are shown in Exhibit 13.11.

Exhibit 13.11 Needs Assessment Flowchart

(a) ASSESS. In the first portion of the process, after determining what information is needed and choosing a method for gathering the information, the assessment is conducted. The broader the sampling (meaning, the greater the number of people contacted for the assessment), the more accurate the results. Methods of assessment include the following four data collection techniques:

- One-on-one interview. The most effective method of gathering information is using an interview technique. The most important steps with this technique are to develop a pre-established list of questions and to conduct the interview without judgment. The art of interviewing for a needs assessment is not dissimilar to playing poker: wearing a poker face, never letting on what information the interviewer hopes to prove or disprove.

- Telephone interview. This method can be very successful, especially if the questions asked are of a personal nature. The lack of face-to-face contact with individuals may make it easier to ask personal questions. However, it also precludes the interviewer from reading facial clues or gestures that are very valuable in changing the interview's tone to probe further on a particular question.

- Meeting. A meeting can be a very effective forum for gathering information for an assessment, although it can be extremely challenging and taxing for the facilitator. Often a round-table discussion will develop as attendees hear how other people answer the questions. This method is also useful in that it immediately identifies where there is consensus and where there will be conflict.

- Questionnaire. The least effective of the four methods, this is the most commonly used because it efficiently allows a broader audience to be contacted. The ability to survey a larger group can often outweigh the benefits of the time-consuming task of one-on-one interviews.

(b) ANALYZE. In this portion of the process, the information collected is evaluated, tabulated, and summarized. You may use a weighting table to give greater emphasis to certain questions in the needs assessment, and you may use return-on-investment analysis to evaluate some investment proposals.

(i) Weighting Table Analysis. Weighting the questions for relevance and applicability to a specific respondent can be very important. For example, if an assessment was conducted with order takers, the response of a person who takes many orders each day or whose only responsibility is to take orders, as opposed to someone who took fewer orders, would have greater relevance. This person's opinions would be more valuable than another's.

When using the weighting table (Exhibit 13.12), answers given by someone who took 1 to 10 orders per day would count one time, whereas the answers of someone who took 51 to 60 orders per day would be counted six times (as if six people had taken the survey).

| No. of Orders Taken per Day | Weight Factor |

| 1–10 | 1 |

| 11–20 | 2 |

| 21–30 | 3 |

| 31–40 | 4 |

| 41–50 | 5 |

| 51–60 | 6 |

Exhibit 13.12 Weighting Table to Determine Relevancy of Answers

Another set of criteria is to weight the answers based on the relevancy of the question itself. Some questions may be much more critical than others. A similar weighting method should be used for each question.

Finally, there may be questions that need to be evaluated against another question, or a combination of questions. For example, if one was asked, “How proficient are you with Microsoft Windows: Excellent, Good, Fair, or Novice?” the question should be balanced with a series of questions specific to Microsoft Windows (e.g., asking specific questions of skills or tasks the person could perform in the program, such as saving a file, opening a file, cutting and pasting). If an individual stated that he or she had excellent skills with Microsoft Windows but answered “no” to the question “Can you open a file in Microsoft Windows?” one could logically assume that the person inaccurately answered the question about proficiency.

(ii) Return on Investment or Benefit-Cost Analysis. To illustrate return on investment (ROI) analysis, or benefit-cost analysis, consider an investment in a treasury management system. There are six treasury information management “value drivers”:51

- Information availability

- Information accuracy

- Information timeliness

- Information system cost

- Automation of information generation, transmission, analysis, and decision making

- “Electronification” of information and payment systems

If someone in the organization proposes an investment in IT, automation, or moving to electronic data or payment transmission, evaluate this proposal using one or more of the value drivers. Then compare the value added by one or more of these items to the overall costs of the proposal to see if it should be implemented.

More formally, you can calculate ROI, net present value (NPV), or internal rate of return (IRR) on IT projects (see Chapter 9 for more on these calculations). A survey found that evaluating computer security software and services is done with ROI (38 percent of respondents), NPV (18 percent), or IRR (19 percent). However, many respondents also note that IT security is a “must-do” item that is implemented regardless of immediate financial impact.52

(c) CRITIQUE. After analyzing the information, it should be determined whether there are results that may be in conflict. In this step, an evaluation of the results is made to verify whether they are as expected or completely off the scale as compared to the original assumptions. Do not assume that the original assumptions were incorrect; but also, do not assume that the results of the survey are correct. Following up with a few respondents may determine that they misunderstood the question or had other reasons (sometimes personal or political) for answering in the manner they did. As a general rule, obscure or irregular results may be disregarded. At a minimum, obscure survey answers should be investigated vigorously. It is possible that the person being surveyed misunderstood the question, but that should never be assumed. It is more likely that there is something unique about the individual's work or assignments that caused the obscure answer. It is just these types of issues that the needs assessment attempts to flesh out. If possible, contact the individuals who provided the answers for a follow-up assessment to gather more information to clarify the issue.

(d) DECIDE. The last step is to make a decision by reviewing the information collected, so an educated nonbiased decision can be made.

(e) IMPLEMENT: GETTING PEOPLE TO USE THE NEW TOOL. It does not matter how wisely the information was evaluated, how successfully the purchase contract was negotiated, or how accurately the needs of the organization were determined, if the staff cannot be trained and motivated to use the tool. If it is not used, the implementation and the tool is a failure. Before making the final decision to purchase or implement, the purpose of the new tool and the willingness or ability of the staff to be trained on it and use it need to be reevaluated. One common complaint of nonprofits regarding technology is that they lack the funds for proper training for staff.

There can be hundreds of reasons why staff in an organization will refuse to use a new tool. Each person may have his or her own specific reasons; however, in general, the reasons a new tool is not used fall into one of the categories described in Exhibit 13.13.

| Reason | Description | Solution |

| ”I don't know how to use it.” | The biggest reason why people will not use a new tool is the most obvious one: They just don't know how to use it. | Provide training in the new tool or system. |

| “I went to the training, but I still don't know how to use it.” | After training is conducted, it is likely that staff will not immediately begin using the system, unless a schedule or an assimilation plan for each individual or group has been created. So often in organizations, staff learn to ignore change as a way of making it go away. | Develop an implementation strategy that includes post-training follow-up. Monitor the progress of each individual or group, setting goals or milestones that need to be achieved by a specific time. Establish rewards (or punishments, if necessary) to encourage meeting these targets. |

| “Training was bad.” | A common complaint about any new system or tool not being used is that the training was ineffective. While it may be considered as a viable reason, it is more likely that there are other causes or reasons besides the training the individual received. |

Evaluate the effectiveness of the training as part of the training process. Avoid the use of “smile sheets” (measurement tools that evaluate only how some liked or felt about the training) as opposed to good measurements that evaluate what they knew before they attended training and what they knew immediately after training. Another important factor in the training program is the relevance to the person's job. If the training examples used are too vague or general, the individual will not be able to assimilate the information. The closer the examples are to the real-life situations or tasks the individual will perform, the more likely the individual will be able to remember (assimilate) the information. |

| “I forgot what I learned.” | Individuals may report that they found the training useful, but it was so long ago that they forgot what they learned. | It is possible that the training was ineffective and the step above should be employed in this example as well. More likely the reason will be that the training occurred too early, before the tool was available. Training should occur no earlier than one month before the tool is available. It is best if the tool is in place before the training is received. |

| “This isn't as good as the old way.” | Looking at information or performing a task in a new way may cause some individuals to judge the process as ineffective. This comment should be interpreted not as a judgment but as a request for clarity about why things needed to change. |

Make sure that staff have the prerequisite knowledge to successfully use the new tool or complete the training course. If a new computer system is being introduced, and staff have never used a computer before, basic computer training must be provided before beginning training on a specific application or system. This prerequisite training does not need to be time consuming or detailed, but provide a basic level of understanding from which the individual can build his or her knowledge of the new tool. |

Exhibit 13.13 Reasons/Solutions for Refusal to Use a New IT Tool

13.9 POLICIES AND PRACTICES IN KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Howard Tech Advisors (HTA) works with numerous businesses and nonprofits regarding their use of technology. Ananta Hejeebu of HTA notes the following three categories of “top IT mistakes” made by nonprofits:53

- Information Security

- Disaster Recovery & Backups

- IT Strategy

Regarding information security, recognize that your organization has confidential data regarding employees, clients, donors, board members, and volunteers. You also have files and photos, intellectual property, bank account data, credit card numbers, passwords, and confidential e-mails that criminals would like to access. Deception comes through fake and/or phishing e-mails, phone calls, access to your laptop when using public wi-fi, or any or your organization's or another party's websites. Security breaches then occur through wire transfers, ransomware (such as Wannacry; ransomware locks down files on your computer and demands that you pay a ransom in Bitcoin before permitting you to regain access to those files), keystroke logging, or data theft with the purpose of selling the data. Consider what data you have, where each type of data is stored, who has access to what data and how might they access that data, and how you can protect your data and reduce your risk.54 Try to draw the appropriate balance between security and convenience of data access. Since people are your biggest risk (and the biggest growth in data loss or theft is from compromises in insider accounts – commonly due to how many of an organization's employees who have unnecessary access to sensitive or confidential data),55 it is essential to limit information so that only those who need to know have access to confidential data and there is a “group policy” configuration to enforce that limit. Password change and secrecy policies are also important, as are an employee termination IT process, limit to company data on personal devices, employee training (security, e-mail best practices, performance reviews, paper document shredding), as well as consideration of cyber insurance coverage.56

Regarding disaster recovery and backups, consider first the incidents of harm: (1) system failure (hardware, servers, cabling, switches, firewall, phone system or handsets); (2) software or data compromise (applications, ransomware, e-mail, and cloud services); (3) theft or catastrophe (people threats, whether internal or external, loss or theft of computer or mobile device, fire, flood); and (4) loss of connectivity or power (Internet services, cloud services, phone services, office/building electricity). Determine which one(s) of these four incident classes are most important regarding cost and risk, then create a plan to deal with it (them). Data protection can come through eliminating local storage (use server or cloud), laptop hard drive encryption, phone wipe policy for lost/stolen devices, determination and assessment of the disaster recovery plans for your cloud vendors, and gaining a greater understanding of the key backup issues.57 Know what is being backed up, where it is saved (local? cloud? both?), whether the process is automatic or manual, whether files, images, or both are being backed up, how far back can you restore from a backup, the last time data was restored or tested, and the expectations for restoring a backup.58

Finally, your IT strategy should begin with a recognition that your technology systems are “mission-critical,” and poor performance may have severe repercussions. View technology as an enabler, not simply a commodity. Strategic thinking entails answers to the following questions:59

- Who in your organization is responsible for technology and is s/he the right person?

- Does your strategic plan include a section addressing IT? (Survey data indicates that just over one-half of nonprofits always or usually do so.)60

- Might technology be used in new/better ways to increase effectiveness, efficiency (automate tasks), or increase contributions and foundation grants?

- Is your organization appropriately leveraging IT tools?

- Might your organization gain more value from its vendors and partners?

Illustrating, in response to #3 you might decide to determine if a cloud offering might be a good fit for your organization. Regarding #5, you might schedule “Tech Business Reviews” every three years with your vendors/partners to review software, your IT plan and goals, your IT budget, and any new capabilities that may have become available.

Regarding budgets and benchmarking, NTEN conducts an annual survey that informs us on nonprofit IT budget amounts for organizations of various sizes. In Exhibit 13.14 we see the results of the most recent NTEN survey. You can compare your organization's IT spending with the spending of similarly sized nonprofits. We caution that “average” does not imply “best practice.”

Source: Robert Hulshof-Schmidt, “NTEN: The Tenth Annual Nonprofit Technology Network Nonprofit Technology Staffing and Investments Report,” May 2017. Used by permission.

Exhibit 13.14 Organizational Spending on IT by Size of Organization

With regard to treasury use of technology, the landscape of available solutions is changing rapidly. As well, there is considerable turnover in nonprofit finance staff. Consequently, expert Dan Carmody offers three key items to implement on an ongoing basis:61

- Create and regularly test a comprehensive treasury disaster recovery plan.

- Benchmark current treasury technology against other marketplace options.

- Review treasury technology user permissions (treasury workstations, bank websites, etc.).

Your nonprofit may gain much from surveying the IT trends faced by businesses along with how they empower and challenge the business CFO and others on the finance team. Exhibit 13.15 profiles these trends. We believe that large nonprofits already face these same issues, and smaller nonprofits will deal with them in the foreseeable future.

Source: Estelle Lagorce, “CFO Primer: 8 Emerging IT Trends That Will Redefine Finance.” D!gitalist Magazine by SAP (May 3, 2017). http://www.digitalistmag.com/finance/2017/05/03/2017-cfo-primer-8-emerging-it-trends-redefine-finance-05062986. Accessed: 7/27/17. Used by permission.

Exhibit 13.15 Technology Trends and Their Impact on Corporate Finance

The 2016 Abila Nonprofit Finance and Accounting Study also unearthed valuable information related to your job and your use of technology. Two of the recommendations that Abila gleaned for us from the survey of nonprofit finance professionals are relevant to IT:62

- Reduce interruptions. These often come from staff in other departments that are requesting bits of information for their planning, budgeting, and reports. You might provide specific times during which they can interrupt your work schedule or provide self-service of often-requested information via customized, role-based dashboards for different departments. You might also consider, especially if you are a part-time finance manager, working from home by using cloud-based fund accounting software.

- Look more closely at the cloud. Respondents mostly agreed that cloud-based technology is superior with respect to cost-effectiveness, efficiency, and ease-of-use. Cloud-based accounting software may enable you to make the most of the small and lean finance staff that is prevalent in nonprofits.

If you would like to learn more and stay up-to-date regarding technology deployment in nonprofits, a great resource is NTEN (the Nonprofit Technology Network; www.nten.org). NTEN hosts an annual nonprofit technology conference and also has an e-mail newsletter, a listserv, and informal interest groups that meet in numerous cities in the United States.63