8

Structuring Successful Projects

8.1 Introduction

Projects go through several stages during their life, from concept to practical completion and handover for operations. There are many activities to be undertaken in order to create a successful project and it is essential that these success factors are properly planned and detailed and then efficiently implemented throughout the process, with constant reviews along the way.

8.2 So What Happens on Successful Projects? What Are the Key Factors that Create Success?

Before looking at this, we need to first define ‘success’. We should aim to achieve the following:

- Build a quality project that meets the aesthetic, technical and functional requirements of the client.

- Delivery on time and on budget.

- Acceptable operating margins for all stakeholders. (Negotiating these requires a reasonable approach by both the client and the contractor, as covered in other chapters of this book and which can be quite difficult at times.)

- Good communications, collaboration and respectful relationships.

- Issues and claims resolved by sensible negotiation; no formal disputes.

- Job satisfaction and adequate remuneration for all stakeholder employees.

- Strong team spirit amongst the stakeholders, with a common objective to deliver a successful project.

- Smooth facility operations after completion of construction.

- Clients and end‐users who are very pleased with their new facilities in all respects.

The following elements for success are fundamental, but it should be remembered that they all have potential for risk; this must be kept in mind and they should be reviewed on a constant basis.

- Competent leadership and professional teams for the client and contractor.

- Clear project objectives that are realistic and achievable – including design, budgets, and programmes.

- Professional consultants, and efficient subcontractors and suppliers that deliver quality work and products on time.

- Efficient contract management platforms and processes – it is important to document everything diligently so that the project history is retained and easily transferable when staff leave. Issues commonly arise when this is not done and staff turnover occurs.

- Careful planning and programming. Do not rush this, because the end result is invariably a direct reflection of the effort put into the planning (see Chapter 24 on the significance of the S‐Curve). So‐called ‘fast tracking’ and/or making an early start on site to impress the client rarely works, and generally ends up costing more and taking longer.

- Realistic and achievable cost plan; contract pricing with a realistic build‐up (do not ‘buy’ work, because if you do then Murphy's Law is bound to apply).

- Appropriately detailed specifications and contract documents (spend extra time on this – it is really worth it).

- Design development running in close parallel with cost planning.

- Healthy project cash flows, with head contractor and supply chain payments in line with programme milestones.

- All parties having a detailed knowledge of their contract documents and contractual obligations (Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) in particular).

- Robust risk management throughout the life of the project, with the key methodology being early warning through constant monitoring and anticipation, together with an inclusive stakeholder communication process.

You will note that all of the above areas have a strong human element, and it is almost taken for granted that the teams involved should be right on top of the technical aspects.

If any of these areas are badly structured or handled, then the effect on the overall project can be serious.

8.3 The Different Activities and Responsibilities, from Concept to Completion of Construction

8.3.1 Building Effective Teams

This is essential for both corporate management and for successful project delivery, and the CEO should be just as much a team member as the site manager. The human behavioural element of all personnel should be a prime consideration for the CEO and senior management when assembling effective teams.

In Chapter 10, Tony Llewellyn outlines the challenge of building teams and puts forward that there are three essential elements required to make a project work, these being technical intelligence, commercial intelligence, and social intelligence. The industry puts a lot of training and value on the first two, and largely ignores the third. The return from these values and the hard work of diligent and efficient team members is seriously diminished if the corporate management is not competent, sometimes with disastrous results for supply chain stakeholders as well as for the projects, and not least the people on site running the projects.

Most people in construction and associated industries devote their lives to it and after even 5 years, let alone 20 or more, it can be devastating to see your company collapsing around you because an incompetent CEO and dysfunctional Board have got it all wrong at the strategic and financial level, with flow‐on effects on projects. At worst your pension might go down the drain, even though the incompetents at the top still take their million dollar salaries and bonuses; rewards for failure are all too common.

This is not being too dramatic. Unfortunately it is just summarising what happens all too often.

However there is a lot to be positive about, as there is clearly a new push by progressive construction companies to greatly improve the quality of their business management, their risk management, and the competency of their site management in order to increase overall efficiency, obtain the budgeted margins, and reduce the incidence of cost and programme over‐runs.

This is taking place through placing more emphasis on having suitably qualified people in the team, all the way up from the site manager to the Board, and through everyone understanding the benefits of better collaboration and communication. Hopefully, the days of employing the ‘dominant yelling sledge hammer’ manager that the industry has been renowned for are nearly over.

All of the above issues are very important considerations in building effective teams. In Chapter 11 we discuss these human resources aspects in greater detail.

8.3.2 Understanding the Bigger Picture

It is important that managers at all levels understand the bigger picture of how their projects are structured so that they are aware of the danger areas. There is nothing more frustrating for a conscientious manager on site or in the head office than to be treated like a ‘mushroom’ and not know the bigger picture. This indicates poor senior management, who cannot work out the difference between essential general information for their staff and confidential higher level information.

8.3.3 Know and Manage the Contract Diligently

It is fundamental that everyone who has management responsibility should have a basic knowledge of how contracts are structured and written, fully understand their terms and conditions in respect of the obligations and liabilities of the parties, and how to apply the contract terms to project management. How this is done will have a huge impact on the progress and efficient delivery of a construction project.

Project managers cannot implement the contract efficiently if they do not fully understand all the terms, conditions and specifications and the rights and obligations flowing from them. They need to know and understand the terms of contract so well that they know immediately where to look in any given situation.

It is then equally important that they carefully comply with the documentation requirements of the contract, as distinct from the technical delivery of the specifications. They must carefully comply with the processes related to administration, such as with the content and time limits for notices, variations and extensions of time. Failure to do so can be a very expensive oversight.

Unfortunately it is quite common to find project managers that do not understand how their contracts work in detail in respect of both the rights and obligations and also the administrative processes, and who rarely look at contracts until they are in trouble. For the majority of the time this trouble might well have been avoided or mitigated if they were on top of their contract and managing it efficiently. It is senior management's responsibility to ensure that their project managers are properly briefed and have the experience and capacity to manage the project efficiently.

In regard to writing the terms of contract, it is amazing how people can take a relatively straight‐forward contract document and turn it into one that contains terms that are ambiguous and difficult to understand, and has grey areas or gaping black holes in respect of the rights and obligations of the parties. It is important to minimise this area of risk when drafting contracts and during the subsequent due diligence prior to signing. The parties to the contract normally work closely in conjunction with their lawyers during the drafting phase.

(Refer to Chapter 12.)

During the drafting, due diligence and checking stages of a contract it is essential to have reviews carried out by experienced ‘seasoned’ project managers to test the contract with some difficult hypothetical situations.

It is really helpful to project managers and others administering the contract, such as the quantity surveyors, if the terms of contract are written as much as possible in layman's language and not in convoluted ‘lawyer‐speak’. Fortunately there has been considerable improvement in this direction in recent years. Likewise, there has been considerable improvement in the general format of contracts.

It is also important to not have too many cross‐references in the terms, both within the main contract and between related contracts, as with PPPs where you have a suite of contracts, such as the Project Agreement, the Finance Agreement, the Construction Contract and the Facilities Management Contract. Some contracts have so many cross‐references that you have to flowchart your way through the documents to find out whom is responsible for what in respect of the rights and obligations of the parties. A simple clause in the Construction Contract may just refer to the Project Agreement, but that particular term may have serious ramifications for the contractor in regard to pass‐through obligations to provide facilities and be responsible for the costs thereof. The facilities manager and their obligations down the track could be affected in the same way.

Contracts that are well drafted will be beneficial for both parties and provide the framework for smooth project delivery, with minimal extra costs and disputed issues, subject to each party managing the contract efficiently and complying with their obligations.

8.3.4 Performance Bonds, Payment Terms, Retentions, and Pricing of Variations and Back Charges

Far too many contractors, subcontractors and suppliers enter into contracts that contain unreasonable and unacceptable terms and conditions and then get badly exploited by their clients.

There must be a level playing field. Clients obviously want their project delivered successfully in all respects, but success is not only dependent on the performance of the head contractor, subcontractors and the suppliers. The client also has to perform efficiently and responsibly. This means being willing to sign a contract that has fair and reasonable specific terms of contract, including the specifications, programme, financial requirements (performance bonds, etc.), payment terms, dispute processes, etc., and the general conditions of contract.

The author was managing director of a tier‐two construction company with a steel fabrication division that operated as both head contractor and as a subcontractor to tier‐one contractors, so we had two types of clients. From my experience there are a few basic rules to stick to, but the basic principle in regard to your clients is that ‘we are builders, not your bankers’.

We used the following terms as the basis for contract negotiations after we had been bitten badly a few times by unscrupulous clients and tier‐one head contractors.

Each client and contract is different and the terms you negotiate will vary accordingly. Our best clients and head contractors had no problem with fair and reasonable contract finance and payment terms because what they really wanted was performance and we were first‐class performers in meeting programmes and delivering quality.

If we were concerned about a client then we insisted on most of the following terms. If they objected, then most likely it was an indication of their intentions towards payments and/or a bullying attitude, in which case we did not want their business anyway. We were also fortunate that we had plenty of work available.

- The terms by which performance bonds can be redeemed are extremely important and must be carefully drafted in quite specific terms in respect of how they can be called upon.

- There should be an upfront establishment payment on signing of the contract to cover advance purchase of materials and site establishment. Depending on the type of contract and the work involved, this can be in the range of 10–20%.

- Progress payments should be geared to milestones, signed off by an independent project Engineer, whose appointment is agreed to by both parties at the outset. We always asked for, and mostly agreed on, payment 14 days after certification by the engineer, but in any case payments should not exceed 30 days after certification, which is normally accepted by government departments and credible clients.

- Retentions should go into an independently managed trust fund, with clear terms and conditions for their release, to be signed off by the independent Engineer;

- Variations – the contract should contain a methodology whereby potential variations must be priced in advance by the contractor and be approved in writing in advance by the client before any work commences. The contract should include a schedule of rates for valuing the variations, or if not applicable then a reference to the use of the going market rate. This protects both parties. In case of disputes the contract should nominate an independent third party empowered to make a decision on the values.

- Back charges by the client – the contract should spell out the methodology and means of valuation in a similar way as with the variations.

- Delay and disruption costs for delays caused by the client – the contract should nominate the methodology for dealing with these, including a schedule of holding costs and ‘Preliminaries’ to be applied.

- In the event of progress payments not being made on time, the contract should stipulate that the contractor has the right to stop work seven (7) days after giving notice in writing, with no penalties applicable and with nominated holding costs payable (as in point (7) above) until work restarts or is formally terminated by the client. Note that we never had to invoke this clause.

- Liquidated damages – most contracts included provisions for LDs, but we never incurred any.

- Penalty/bonus, in lieu of LD's. This is not a common arrangement, but we really liked it. The general rule is that you cannot have one without the other, so typically you might enter into a contract that has a fixed completion date, subject to any agreed EOT's under the terms of the contract, and fix the penalty/bonus at say $3000 per day either way. The largest that we had was US$10000 per day;

- Final payment – if you are really concerned about the financial standing and intentions of the client/head contractor you could ask for the final 10% to be lodged as a bond with a third party, e.g. lawyers or bank, to be released on final certification by the independent Engineer. We only ever asked for this with new clients that we were unsure about.

In summary, the main objective is to structure your cash flow so that it is always positive in terms of receiving more than your own costs to date and what you owe creditors, at every stage in the programme, so that if the project stops for some reason or other, including the client going bust, then you will not be ‘out of pocket’. Realistically, this can be difficult to achieve on some contracts, but you should only allow yourself to get into a negative cash flow position if you have absolute faith in the client's solid financial situation and integrity.

8.4 Checklist for Structuring Successful Projects

The following processes and procedures can be used as a checklist for most construction projects. They will nearly all apply to PPPs, but to a much lesser extent with D&C or construction‐only projects.

The parties responsible for the following processes are identified in italics (client, contractor, user/operator, facilities manager (FM)):

8.4.1 Structuring the Project (Client)

- Concept – the schematic design and the business case

- Client financing – concept stage and whole of project

- Site acquisition

- Planning and other authority approvals

- Feasibility studies

- Preparation for tender – assessing the overall project; the common sense of the concept

- Assessing the degree of readiness to proceed

- The client's own resources and competency

- The political situation

- Calling for expressions of interest (EOI's) and planning the tender.

8.4.2 Tendering and Bidding Activities (Client, Contractor, User/Operator, FM)

With traditional contracts it is essentially the responsibility of the client to manage the process, but with D&C and PPP projects there is also substantial involvement from the contractor, the future operator (end‐users, e.g. National Health Service) and the facilities manager.

- Preparing the tender documents – drawings, specifications, special terms and conditions

- Design development and cost planning in parallel for D&C and PPP projects

- Establishing the risk management processes

- Consideration of operational items – end‐user requirements, O&M, life cycle replacement

- D&C planning and programming

- Firming up prices – subcontractors and suppliers

- Bid qualifications

- Due diligence on contract documents

- Client check of financial strength and experience of all participants in the Bid (should have occurred during assessment of EOI).

8.4.3 Establishing the Risk Management Process (Each Party is Responsible for their own Risk Management)

The extent to which this is done will depend on the size of the project, but at the very least a risk management schedule should be prepared that covers all areas of the project. Large projects should appoint a specific Risk Manager whose task it will be to consolidate and monitor all of the potential risks that are nominated up‐front by the different section managers. Refer to Chapter 17 for further elaboration on this point and a typical team structure and flowchart for controlling risks.

8.4.4 Finalising the Financing and the Contract

- Establish realistic and carefully prepared budgets and cash flow projections for progress claims and milestone payments (client, contractor).

- Have a realistic contract sum analysis and scheduled rates for overheads, preliminaries and margins (contractor).

- Agree fixed margins in the contract for modifications/variations for the contractor, facilities manager and equity partner in the case of PPPs, so that arguments over future variations are minimised (client, contractor).

- Ensure the financial structure has some flexibility and headroom for variations (client).

- When preparing PPP contracts, place heavy concentration on the services scope and obligations in the contracts (client).

- Test the contract as much as possible to eliminate black holes, grey areas and ambiguities (client, contractor).

8.4.5 Establishing the Project Leadership and Team Spirit

Early appointment of a top‐line project director by each of the main stakeholders.

Establish and demonstrate real leadership from the outset, through a stakeholder workshop held immediately after signing the contract, or financial close for PPPs (client):

- To establish relationships, relationship management and guiding behaviours

- Commence building trust and respect

- Understand the needs and success factors of all stakeholders

- Establish common goals; agree key objectives and mission statements; e.g. ‘a world model PPP’ and ‘no disputes’

- Generate positive attitudes and create team spirit.

Run Review Workshops at least every four to six months – the main things that will need ‘renewal’ will be relationships, communications protocols, and project objectives – remember that staff changes are always happening (client).

8.4.6 Agree the Key Processes with All Stakeholders at the Outset

- Control and reporting requirements and procedures – client, project or SPC manager, contractor, design consultants, FM.

- Management and document control platforms with different levels of access, e.g. Affinitext, Team Binder, Incite, SharePoint, etc.

- Communications protocols – establish clear rules – no side‐plays.

- Meetings and working groups – strict rules – with timetables, mandatory attendances, agendas, delivery times for minutes – chaired and proactively led by project directors.

- HS&E regimes.

- Crisis management planning (see more detail at the end of this chapter).

8.4.7 Construction Phase (Contractor, FM)

- Financing, staffing and allocation of resources

- Org charts and job descriptions

- Planning and programming

- Detailed design development, again in parallel with the cost plan

- Full involvement of the FM from day‐1 – ‘whole of life’; O&M practicality and optimisation; ‘granite can be cheaper than bricks over 25 years’.

8.4.8 Commissioning, Completion and Transition to Operations (Client, Contractor, User/Operator, FM)

- Ensure enough time is allowed for commissioning and provide adequate resources – PPPs can take far more time and resources than normal D&C projects, which traditionally might only be 95% finished at practical completion and the remainder is completed during the defects liability period (see Chapter 15 on PPPs).

- It is a common error to cut short on resources and the time allowed when budgeting, but this can prove expensive in the long run.

- Programme the activities carefully, with participation and agreement from all stakeholders, particularly the client, user/operator and the facilities manager, who will take over full control during the transition period.

- Do not confuse completion, commissioning, and transition. Treat them as entirely separate activities and plan, programme and resource them accordingly

- Experienced commissioning and transition managers should be engaged – the transition manager's role is to liaise with and coordinate the activities of all stakeholders and is not the same as the commissioning manager, who comes from the contractor

8.4.9 Defects Liability Period (Client, Contractor, FM)

- Plan and programme the management and resourcing for the rectification of the defects in conjunction with the relevant subcontractors.

- PPP projects, hospitals and prisons in particular, are more difficult than traditional construction or D&C projects as it is necessary to be 99.9% defect free at project completion, for two reasons:

- The independent tester will require it under the contract

- Access for fixing defects will be restricted as soon as the facility goes into the operations phase.

- Form subcontractor ‘task teams’ for an efficient rectification process, comprising a skilled tradesperson from each specialist subcontractor involved with defect rectification (snagging in the UK), probably four or five of them in total, and have them work together as a team, e.g. in a hospital, room by room down a corridor, securing each as they are signed off defect free. Note: this is the most practical, efficient and cheapest method.

- An interface agreement should be in place between the contractor and the facilities manager, with the FM being responsible for all but major items involving warranties, such as large equipment breakdown.

- It can also be cost effective for the contractor to subcontract the management and completion of the defects to the FM after the bulk of them have been fixed.

8.4.10 Claims and Disputes (All Parties)

- Establish clear methodologies in the contract and in the early stakeholder working sessions for reviewing and processing claims. Stick to strict time schedules for processing claims, because they only get harder the longer they are left.

- Ensure that the contract includes a workable dispute resolution section. All too often this is left to the last minute and something is included in a rush without proper thought.

- In structuring the dispute resolution process, ensure that there is an emphasis on negotiated settlements, with plenty of opportunity for this to take place.

- In D&C and PPP projects, encourage the parties to adopt value engineering ‘trade‐offs’ when design and equipment changes take place during design development, with the objective being a cost neutral result. This is a good way of minimising potential future disputes over variations.

8.4.11 Crisis Management Planning (All Parties)

A crisis on a construction site is very much a human behavioural situation and you can never be sure how people will react under the stress of a crisis. It is important that each project establishes procedures at the outset for crisis management and crisis communications and that everyone working on the site or connected with the project through one of the stakeholders is inducted into the procedures.

The two crisis procedures, management and communications, are equally important; e.g. if there is a serious accident on a site the treatment and evacuation of the injured person has paramount importance, but at the same time it is essential to communicate details of the incident promptly and in the right manner to the family of the injured person and to the CEOs of the construction company, the client and the subcontractors that are involved, because the last thing you want is for them to hear about it first from a reporter or on the TV news.

There are a number of potential crises that can occur on a project and procedures should be developed to handle these different areas of risk.

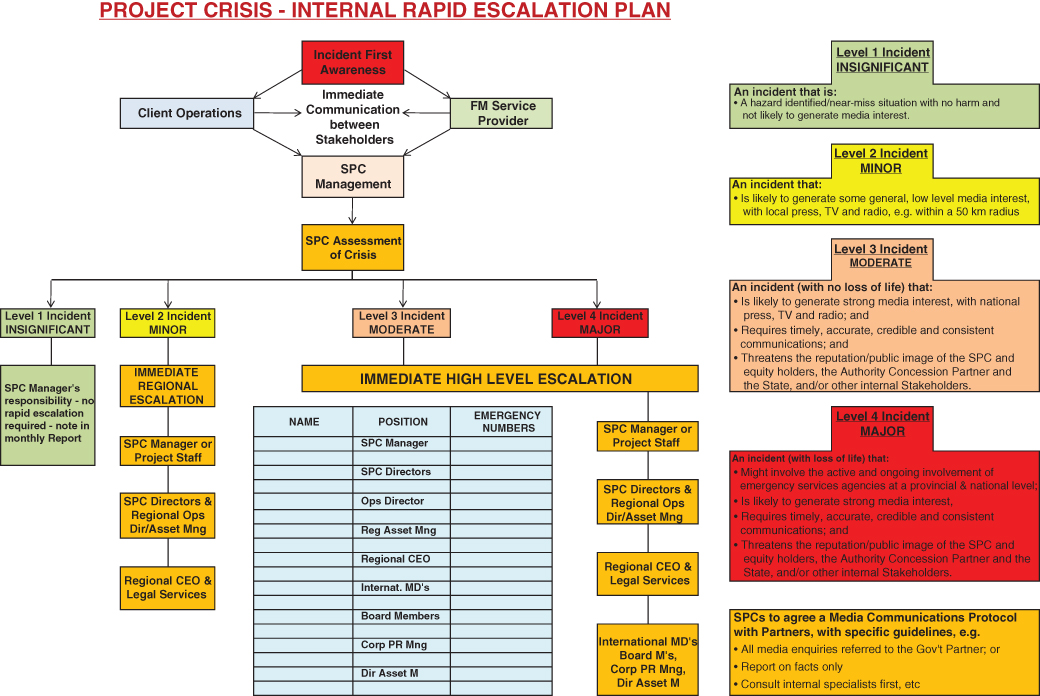

The ‘Project Crisis – Internal Rapid Escalation Plan’ (see Figure 8.1) is a typical crisis communication plan for stakeholders, which can be extended to cover the media and the community.

8.5 Summary

There is absolutely no substitute for thoroughly detailed planning. Successful projects don't just ‘happen’. They directly reflect the thought and degree of detail that goes into the planning and preparation of the documentation for all stages, followed by efficient implementation. Only by doing this will you achieve ‘success’ as we defined it at the beginning of this chapter.