No Surrender

THERE ARE SOME who suggest that the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs’ position during the 1970s and the position of all First Nations that refuse to sign termination agreements with the government—which includes the majority of Indigenous peoples in the B.C. Interior—is to reject all development. Nothing could be further from the truth. We simply understand that the cause of our poverty, and of the enormous distress that comes with it, is the usurpation of our land. The only real remedy is for Canada to enter into true negotiations with us about how our two peoples can live together in a harmonious way that respects each other’s rights and needs. We are looking for a partnership with Canada, while Canada is trying to hold on to a harmful and outdated colonial relationship.

We well understand that economically and environmentally sustainable development of our lands is essential. As long as development respects the integrity of the land and minimizes its impacts, we must take advantage of opportunities to build diversified economies that also take into account the modern imperative of clean energy—which is required to save our planet.

Soon after the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, I saw how development can be handled in a much different model. In 1976, a year after the Cree signed the James Bay Agreement, Ron Derrickson was elected chief at Westbank, the Okanagan community across the lake from Kelowna. He showed through his deeds that a community could develop its land without selling or ceding it to the Crown—in fact, by making the community’s collective ownership of its land an economic asset.

At the time, Chief (now Grand Chief) Derrickson was already a successful businessman, who had built his business the hard way. He was born into his family’s small farm on the Westbank reserve, where his father was barely able to eke out a living to keep his family fed. When he was school-aged, Ron and his brother were sent to the white school in Kelowna, but they encountered such racism that they soon transferred to the nearby residential school. There, at least, they would not be hounded by white bullies.

Derrickson left school at a young age and worked in the orchards of Washington State. Eventually he moved to Vancouver, where he learned the welder’s trade. Always a hard worker, he lived frugally and saved enough money to return to Westbank to buy a small ranch. Over several years, he purchased small strips of land and built a number of mobile home parks. Later he invested in more capital-intensive developments like marinas, recreational developments, and real estate. Today he is the owner of more than thirty businesses.

When he was elected chief in 1976, Derrickson immediately put his business knowledge and experience into developing the Westbank economy. Over his first five terms as chief, from 1976 to 1986, he brought about a dramatic rise in revenue for the band and in the standard of living of his people. He accomplished both his private business and the later band development by using the existing tools for Indian on-reserve business: Certificates of Possession (CPs).

Most people think that Indian reserves are without private property, but there has been a system in place since the beginning. In our own Secwepemc culture, families had recognized places on the river for their fishing camps, their own traplines, and territories for their mountain base camps and for their wintering houses. These lands were passed on from generation to generation. They were not formally marked off; everyone simply knew exactly what belonged to whom. Today almost half of the Indian bands in Canada continue with this custom allotments system of ownership.

The others operate on Certificates of Possession. CPs have been around since the original Indian Act in 1876, when they were called Location Tickets. They give individual band members individual lands in a formal way, but still largely based on the original custom allotments. But while a CP gives the holder lawful possession of an individual tract of land, it is fundamentally different from the fee simple title that Canadians use.

For reserve land to be allotted to individuals through Certificates of Possession, it requires first a land survey and a band council resolution. Then it requires the approval of the Department of Indian Affairs. The CP is then sent to the band council, which forwards it to the title holder. With a CP, band members can pass on the land to their children or sell it to another band member. What they can’t do is to sell it to non-Indians, and it is protected from forfeiture by any individual or corporate entity, such as a financial institution. So it is not something that can be directly mortgaged in the way that you mortgage fee simple lands. This means it can never be truly alienated from the community.

It does not prevent you from developing the land, though. Instead of mortgaging it, you can lease it long-term. This can be done by either individual or band CP holders, although it requires approval—which generally moves at a bureaucratic crawl—from the Department of Indian Affairs.

It was this leasing system that Chief Ron Derrickson used to develop the Westbank First Nation. He was able to take advantage of the fact that the community was just across the lake from the rapidly growing city of Kelowna. The land’s value was increased when the province built the Connector highway, a faster route to Vancouver joining the Okanagan Valley to the Coquihalla Highway, along the southern edge of the reserve. The band began to lease these lands to businesses, and suddenly a new revenue tap was opened up to the people of Westbank. Today, it is one of the most prosperous Indigenous communities in Canada, and this was done without surrendering an inch of land.

While Chief Derrickson was working to build the economic future of his people, my life was one of wandering. I had returned briefly to British Columbia in 1974 to work with Philip Paul at the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs. My contract was to organize a demonstration to mark the fifth anniversary of the White Paper. By then, it was already clear that while the White Paper had been formally withdrawn, the broad outline of the policy—terminating the legal existence of the First Nations in Canada—remained the central drive of the Liberal government and the Department of Indian Affairs.

Travelling through the back roads of British Columbia was an important education for me. I drove a beat-up old Chevy on potholed dirt roads to remote communities, and everywhere I was confronted with the systemic poverty of the people. Communities left in Third World conditions with little access to education and health services. Living on a tiny percentage of their lands and surviving on what amounted to a few dollars a day under the Indian welfare system.

But even with all this, it was not a sombre experience. Along with the poverty, I encountered the richness of the cultures, pride, and a sense of resistance to the outside forces. I spoke to dozens, even hundreds, of Elders and youth, and they did not need me to tell them we had to continue to fight government encroachments on our rights. They understood all too well the source of their poverty and the solution to it. It was not a philosophical question, but something that they had in their DNA. The land was theirs, it was given to them by the Creator, and they would do whatever was necessary to get it back.

After my sojourn in British Columbia was over, I went to Quebec as a youth worker, but I can’t say that this period was particularly useful for me. I had a contract as a youth coordinator for Chief Andrew Delisle’s Indians of Quebec Association (IQA), and I soon found myself in an uneasy situation. It was in the run-up to the Montreal Olympics, and Chief Delisle and the IQA had already accepted to participate in their assigned role of providing local colour to the ceremony. When I met with the youth, I discovered they pretty well detested everything that the IQA—with its conservative and deferential approach to Aboriginal title and rights—stood for. When the youth, with me standing with them, began protesting the preparations for the 1976 Olympics as a way of bringing attention to the land question in Quebec, I was quietly laid off from my job.

I stayed on in Montreal and attended Concordia University without any academic plan, spending most of my free time working with a group that was trying to set up a Native Friendship Centre in Montreal. Eddie Gardner was the head of the founding group, but I was temporarily made president when they needed someone who could do a little fist pounding to get official accreditation from the national organization of Friendship Centres. We succeeded. Eddie took over again, and I continued with my directionless studies.

My life was changing during this period. Now in my mid-twenties, I was no longer part of the “youth.” On my trip back to Neskonlith in 1974, I had met Beverly Dick, a beautiful and intelligent Secwepemc woman, and we soon became a couple. She had been raised in a traditional way by her grandparents and had avoided residential school, so she still spoke our language. She returned to Montreal with me and we were married there. Our twin daughters, Mandy (Kanahus Pa*ki) and Niki (Mayuk), were born in 1976. We would have five children together. Neskie was born in 1980, Ska7cis in 1982, and Anita-Rose (Snutetkwe) in 1986.

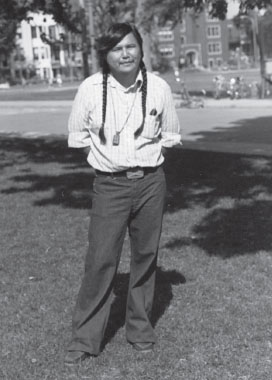

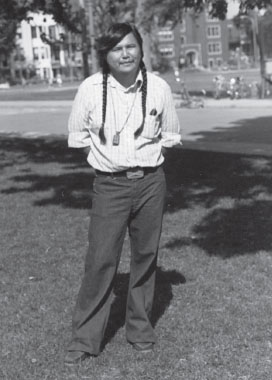

Montreal, July 1975

The arrival of the twins made me realize that I had to get more serious about my life. I had a family to support. I decided the best way to take care of my family and continue the struggle for my people was to go to law school. I was part of a small wave of young activists of my generation who saw the law as a promising avenue for the struggle to have our rights respected. I think the Supreme Court’s Calder decision had something to do with that. Trudeau had mused that we had more rights than he thought, and we were determined to see how far we could push that.

I buried myself for several months in LSAT preparations, which require an enormous amount of work. I took the LSAT at McGill University, and applied and was accepted at Osgoode Hall at York University in Toronto. I then took the six-week preparatory course offered through the Native Law Centre at the University of Saskatchewan.

At Osgoode, it was not easy to find anyone with expertise on Aboriginal issues. No one at law school was interested, and I felt isolated there as I constantly tried to find ways to apply what I was learning to the struggle for recognition of Aboriginal title and rights. I did have a genuine respect for the law professors, though. They stressed that we were not there to learn about the law, but about how judges made decisions on the law. An important distinction when you see how interpretations of the same laws evolve through time, especially the laws related to my people.

In a personal sense, I was moving from the streets to a challenging and competitive part of the academic world, and it was a big step. My law school experience afforded me the opportunity to study the huge amount of colonial material you have to understand in order to understand the true plight of Indigenous peoples. It provided me with the legal framework to think through Aboriginal and treaty rights problems and understand them in relation to national and international human rights. It also helped me understand the limitations of seeking justice solely through the courts.

Our legal decisions always have that political element that, if we want to see the legal opinions implemented on the ground, requires us to also get the co-operation of the federal and provincial governments. And for that, we must be able to put political pressure on the governments to force them to act. In the last twenty years, I have been working at this on the economic and international civil rights spheres. It will not be lawyers, Indigenous or otherwise, who will bring the fundamental changes we need. That power, I am more convinced than ever, rests with the people themselves.

In the end, I did not finish law school. I left still needing to complete one field course on family law that I had no interest in. I have no regrets about leaving before completion, because I know that even if I had graduated from law school, I would never have practised law. I would be doing exactly what I am doing now.

My father was also seeing the need for a people’s movement to break the deadlock. He left the presidency of the National Indian Brotherhood in 1976 with the idea of trying to build a movement to try to effect fundamental change. By then, he had decided he had gone as far as he could in Ottawa. He had helped build a fairly highly functioning national organization, and he had carved out a place for Indigenous issues on the national agenda—where there had been none. Indians were able to get a hearing, at times at the highest levels, and there were small gains in a number of areas like health and education. But the gains were always small. My father realized that our people could not simply lobby their way into justice.

One of the avenues for fundamental change, he knew, passed through international institutions. And some of his most important activities during this period were devoted to building up the World Council of Indigenous Peoples, which he had established at a mass meeting of Indigenous peoples from around the world that he organized on Vancouver Island in 1975. After he stepped down from the NIB leadership, he undertook extensive travels to solidify the World Council.

At the back of his mind was the idea of returning to British Columbia to try to build a grassroots movement to push the sort of anti-colonial struggle our situation called for, a struggle that would work to decolonize first our minds and then our lands. But when he returned to the province in 1977 to take over the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs and build the people’s movement, he found an organization racked by internal dissent. A number of the key coastal leaders, notably Bill Wilson and George Watts, had left the Union and were openly trying to build a rival organization. I will not go into detail here about that battle, as it has already been chronicled by others. But I did have personal evidence that the break with the Union by the dissident leaders was, if not orchestrated, at least strongly encouraged by the Department of Indian Affairs.

My accidental insight into this situation came while I was a guest in an Indian Affairs car being driven downtown from the Vancouver airport. I was just out of law school, living in Ottawa, and had flown to a meeting in Vancouver with the Anishinabe lawyer David Nahwegahbow. We met Indian Affairs Minister John Munro and his Indian assistants, Raymond Goode and Danny Grant, on the plane. David and I knew Raymond and Danny well, so we struck up a friendly conversation with them. As we neared Vancouver, Raymond said they had a couple of cars coming from Indian Affairs to pick up the minister and his staff and offered us a ride in the staff car. We accepted the offer thinking that, really, things did seem to be changing at Indian Affairs.

But when we got into the car, the driver, an Indian Affairs official, assumed that David and I were also Munroe’s Indian assistants. So during the long drive into the city, he cheerfully described a litany of underhanded actions the Vancouver office was taking to undermine and divide the Union, including secretly supporting the dissidents. Danny, who was in the front seat, turned around with an embarrassed smile on his face and Raymond sat with a frozen grin while the white official spilled the Indian Affairs beans to David, an activist Indian lawyer, and me, the son of the president of the Union. Neither Raymond nor Danny said a word to stop the outpouring from the white guy. I suspect, in their own way, they were pleased to see DIA exposed for what it was.

For me, it was good to be reminded of the type of people, despite their occasional attempts to charm us, we were dealing with at Indian Affairs. As soon as I was out of the car, I called my father with the news. He wasn’t shocked by it at all. He’d known all along about the leadership role the Department was playing in splitting up the Union. His response was to go ahead and try to build the people’s movement.

Within the Union, they were working first on an Aboriginal Title and Rights Position Paper that listed twenty-four areas where First Nations had to recoup rights and powers that had been usurped by the governments. I will quote sections of the position paper here, because it gives a clear contrast to the position taken by those Indigenous leaders who accepted “cede, release and surrender” as the only option.

In its preamble, the position paper states that it “represents the foundation upon which First Nations in British Columbia are prepared to negotiate a co-existing relationship with Canada.” It begins with an invocation of where our rights come from:

The Sovereignty of our Nations comes from the Great Spirit. It is not granted nor subject to the approval of any other Nation. Our power to govern rests with the people and like our Aboriginal Title and Rights, it comes from within the people and cannot be taken away.

We are the original people of this land and have the right to survive as distinct Peoples into the future;

Each First Nation collectively maintains Title to the lands in its respective Traditional Territory;

Economic Rights including resource development, manufacturing, trade, and commerce and fiscal relations.

National Rights to enjoy our National identity, language and history as citizens of our Nations.

Political Rights to self-determination to form our political institutions, and to exercise our government through these institutions, and to develop our political relations with other First Nations, Canada and other Nations of the World.

Legal Rights to make, change, enforce and interpret our own laws according to our own processes and judicial institutions including our own Constitutions, systems of justice and law enforcement.

Citizenship Rights of each individual to human rights as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The conclusion of the paper is unequivocal:

Our people have no desire, under any circumstances, to see our Aboriginal Title and Rights extinguished. Our People Consistently state that our Aboriginal Title and Rights cannot be bought, sold, traded, or extinguished by any Government under any circumstances.18

This is the bar, set more than thirty-five years ago, below which no negotiation with governments can fall. No nation on earth should be forced to enter a negotiation that is destined to end with its own extinguishment. The demand that we extinguish our Aboriginal title and rights is an attack on the fundamental rights of our people and a contravention of our basic human rights as set out in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which even Canada finally felt compelled to endorse in 2010. The UN has explicitly recognized that in its essence, “extinguishment” contravenes international law and “the absolute prohibition against racial discrimination.” As the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples observed in 2010: “No other peoples in the world are pressured to have their rights extinguished.”

Some might argue that all people have the right to do whatever deal they want, including to extinguish their sovereign rights. The problem is that the birthrights they are selling are not theirs alone, they are those of their children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. And those we do not have the right to sell.

When these battles were being fought in British Columbia in the late 1970s, the first issue the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs took up was fisheries. The government had enacted a plethora of regulations against our Aboriginal right to fish and maintain an economy based on fishing. After launching a province-wide campaign with a Fish Forum in Vancouver, and arming itself with legal opinions, the Union supported a series of symbolic “fish-ins” around the province. In Lillooet, this symbolic act resulted in scuffles and fistfights when twenty-four Department of Fisheries officers descended on the protesters and tried to muscle them off the river. As tensions rose, the Union didn’t back down. It issued a press release stating that it would “meet violence with violence.”

At a 1978 assembly in Penticton, my father said the fishery was just the first battle. “Self determination has to be our goal in our quest to recover the lands, energy, resources and political authority that we have entrusted to the White political institutions. We are saying that for the past hundred years we gave you, the White government, the responsibility to manage our lands, energy, resources and our political authority. You have mismanaged that trust and responsibility. Now we are taking it back into our hands and we will manage our own resources through our Indian political institutions.”

The next issue was child welfare. In 1980, the Union led a massive march on Victoria to demand the government stop scooping our children from our reserves and placing them outside of the community. The impetus for this action came from a young Splatsin Chief, Wayne Christian, who had passed a resolution in his community insisting that Indian children would be cared for in the community, except in the most exceptional circumstances. The B.C. Indian Child Caravan moved through the Interior picking up supporters along the way, until more than a thousand people took to the steps of the legislature demanding a meeting with the minister for Child Welfare, Grace McCarthy. Finally, it took the 1981 three-week Women’s Occupation of the B.C. Department of Indian Affairs regional office to win full control of Indian communities to care for their children, an occupation my own mother was part of and was arrested for. The Child Caravan was the opening shot in that ultimately successful Union battle.

British Columbia was in ferment, and my father was emerging now as the war chief of the movement. He was not the only member of my family involved. I had just finished law school when my brother Bobby suddenly emerged onto the national scene to run for the position of national chief. He was still in his early thirties, but he had already made a name for himself in B.C. Indian politics, and he became the torchbearer of the people’s movement on the national scene.

Like most Native youth, Bobby had spent a few years trying to find his place in the world. He worked at mill jobs to earn a little money and moved around to see a bit of the country. In 1970, he had a driving offence with a $250 fine that he couldn’t afford to pay. To escape a jail term, he headed down to Washington State to pick fruit and lay low for a while. But he received the same surprise visit from our father that I had had as a teenager in residential school.

It must have been an interesting meeting. After we had run into him at the Chase train station on our way to Chilliwack with my mother, Bobby had in fact spoken to my father when he saw him in town. He’d told him, “You don’t have a family anymore. They all left!” That was a measure of the youthful anger and resentment he held. But when my father travelled down to Washington to meet with Bobby, several years had passed. Bobby was in his early twenties and my father was beginning to recognize the mistakes he had made with his children. He came to make amends. It was during the period that he had taken his strategic vacation to allow Harold Cardinal to do the politics required to get him elected as president of the National Indian Brotherhood, and visiting Bobby was his first stop. He counselled his eldest son to go back to British Columbia and deal with the legal problem, and he suggested he go to see Philip Paul, then the director of Camosun College. When my father returned to Alberta, he sent Bobby a signed copy of Harold Cardinal’ s newly published book, The Unjust Society.

My father’s visit set Bobby on his own path of activism. Philip Paul took Bobby under his wing, and Bobby enrolled in a course at Camosun on community development. When he returned home to Neskonlith a couple of years later, he was elected chief. Bobby also became active in the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, where he was a member of the executive in 1977 when my father returned to B.C. to head the Union.

As a leader, Bobby had earned his own base of support across the province, where he was seen as a young, soft-spoken activist with an uncompromising conviction on our Aboriginal title and rights. In 1980, in a last-minute campaign, he took that message to the chiefs across the country when he ran for the National Indian Brotherhood presidency. He began as a long-shot candidate, but by the time the votes were counted, he lost by only a single vote to the much less confrontational Del Riley. It was a message to the government that something serious was brewing in Indian country.

An even greater challenge was waiting just around the corner. In the months before Bobby ran for national chief, my father had visited me at law school. The constitutional issue had been on and off the Canadian agenda for the past decade. Prime Minister Trudeau had tried to patriate the BNA Act from Britain in 1971 and failed when Quebec premier Robert Bourassa withdrew his support. By the end of the decade, Trudeau was trying again to get consensus from the provinces and warning that if they refused, he would do it unilaterally.

This issue was in the news in the spring of 1979 when my father visited me in Toronto. That evening, he told me he was trying to understand the full implications of constitutional patriation for Indigenous peoples. His first thought was that maybe we should just stay out of it, that it was a non-issue for us. And wouldn’t trying to get recognition of our rights in the Canadian Constitution imply that we were part of the country—and therefore put in question our sovereign rights?

I disagreed. After almost three years in law school, I understood that the Constitution was where all of the rights, including territorial rights, were sorted out. It was the document that the courts looked to hold governments to account. If we were not in there, we were not in the game at all.

In the BNA Act, the British had allocated all of the powers in Section 91, which outlined federal powers, and Section 92, which outlined provincial powers. There was no room at all for Indian power. Our sovereignty was effectively stamped out in Section 91(24), which gave the federal government complete control over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians”—in other words, over our lives. After approving this colonial document, the British sent it across the ocean to their successor state. We had to turn to older British constitutional decisions, like the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to find any Indigenous rights at all. And we had to hold the British government to task for our exclusion from the BNA Act, in what is essentially a white supremacist constitution, and find a way to break the Section 91 and 92 stranglehold on power.

When he left my flat in Toronto, my father still seemed unconvinced. But when, immediately after the failed Quebec referendum on independence in May 1980, Trudeau was ready to move on his threat to go it alone, and include in the repatriated constitution a Canadian charter of rights and freedoms, it raised alarm bells for First Nations across the country. Even after ten years, the White Paper battle was still fresh in our memory. What would happen if the charter of rights and freedoms could be interpreted to remove our Aboriginal status and protection of our lands in the name of “equality” with other Canadians?

The worst was confirmed in June 1980 when the Continuing Committee of Ministers on the Constitution released a twelve-item agenda for the constitution that did not include a word about Aboriginal title or rights. The Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs immediately launched a court action to block patriation without the consent of Aboriginal peoples.

At the end of the summer in 1980, while the Child Caravan was still marching on Victoria, the Union met to review the federal government’s repatriation plan and a decision was taken. The chiefs passed a resolution that “the convention gives full mandate to the UBCIC to take the necessary steps to ensure that Indian Governments, Indian Lands, Aboriginal Rights and Treaty Rights are entrenched in the Canadian Constitution.”

By November, the Union launched a massive operation to fight any patriation of the constitution without the explicit recognition of Aboriginal title and rights. The Constitution Express was born.