A Grassroots Movement

THE CONSTITUTION EXPRESS was an expression of a people’s movement that changed the country in a fundamental way. Both the issues it addressed and the organization of the protest have important implications for our struggle today.

My own role in the protest was minor, but I was at Ottawa Central Station when the train pulled in on the morning of November 28, 1980. Two trains, with more than a thousand protesters on board, had left Vancouver four days earlier, taking different routes through the Rockies and joining together in Winnipeg, where they stopped for a night of rallies hosted by the Manitoba Indians.

In gathering support for the constitutional battle, the journey had already been a success. In British Columbia, hundreds of Indians had met the trains as they passed through the towns and cities along the route. In Alberta, the crowds reached the thousands. By the time the train left Winnipeg, the whole country was watching. The national news media were filled with speculation of what this Indigenous army would do when it reached the capital. In Ottawa, the RCMP began to fortify Parliament Hill with riot gates, and rumours of violent confrontations began to circulate.

By this time, Canada was in its own turmoil over the constitution. That September, after the failure of a last-ditch federal-provincial constitutional conference that our people were excluded from, the prime minister announced that he was moving ahead as promised to request unilateral patriation from Britain by a simple Act of Parliament. His idea was to move quickly enough that patriation would be a fait accompli before the Supreme Court had time to make a ruling on the Indigenous case and another attempt to block patriation filed by eight of the ten provinces. All the British had to do was to take a quick vote to approve the Canadian changes, and the deed would be done. Politically, Trudeau knew it was impossible for the premiers—even those most set against patriation and the charter of rights—to argue that the constitution, once patriated, should be sent back to Britain. Or that a charter of rights, once adopted, would be abrogated.

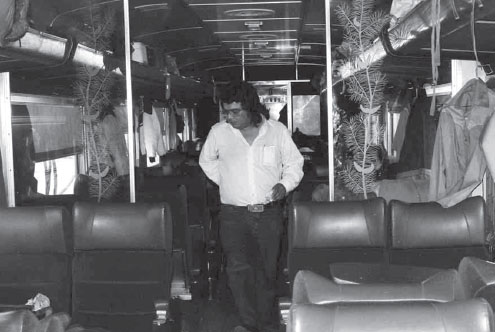

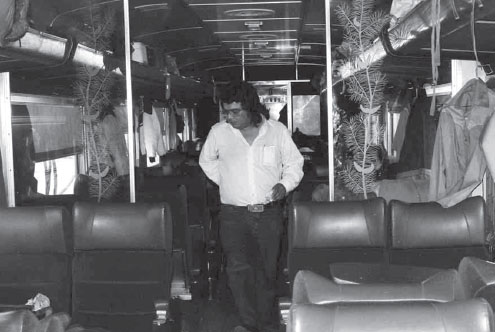

Chief Robert (Bobby) Manuel, Constitution Express, November 1980

Prime Minister Trudeau presented his constitutional package for passage by the Canadian Parliament on October 2, 1980. Even though most of the provinces opposed the move, polls showed that he had the support of the majority of Canadian people. He also had the support of the New Democratic Party in the House of Commons.

For Indigenous peoples, it was an example of the often sharp differences between us and non-Indigenous Canadians. For the average Canadian citizen, particularly for English-Canadians, the battle between the premiers and the prime minister was a jurisdictional one between two levels of government. Most wanted a deal to be worked out that provided the benefits of patriation and the charter of rights and preserved the current balance of power, but the worst that could happen is that some power would shift from the provinces to the centre. For us, just as much as in the case of the White Paper, our future as peoples was at stake.

In the “equality” provisions of the charter of rights, the federal government would have the tools to undermine our nations by stripping away Aboriginal rights that were not the same as those as other Canadians enjoyed. At the same time, patriation presented us with an opportunity to correct the exclusion of our rights from the 1867 Constitution, which had given all power over our lives and our lands to the federal government. The protection of our Aboriginal and treaty rights in the new constitution was a question of our very survival.

The thousand grassroots protesters on their way to Ottawa on the Constitution Express were demanding that the recognition of Aboriginal title and treaty rights be explicitly written into the constitution. On the train, the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs activists, which included my brother Bobby, were running workshops on the constitution and on what it would mean for our rights. They also laid out plans for demonstrations in Ottawa and stressed the need for discipline from all of the participants.

As the Union information package told participants: “Trudeau has challenged the Indian people to prove that we have our own rights and freedoms and these have meaning for us. We must show him in the courts and we must show him to his face. We must take as many Indian people to Ottawa as we possibly can.” The Union also stressed the utmost discipline from all participants because “the Government can only hope to make us look bad. We cannot tolerate any alcohol or drugs. This is a very very serious journey that we are undertaking, to defend our existence as Indian people.” To ensure discipline, those chosen for the security detail on the trains had been given both physical and spiritual training.

The people on the trains remember the great cultural celebration as they crossed the country, with singing, drumming, and Elders speaking. The protesters drew strength from this celebration with every mile along the track.

They were also made aware of the fears they were generating in official circles. At one point, between giant granite rock cuts in the Northern Ontario bush, the train suddenly screeched to a halt. RCMP officers poured onboard. Bobby asked the RCMP what was happening.

“Bomb threat,” they told him. “Everybody off the train. And take your luggage with you.”

Bobby looked outside and saw that they were trapped between the granite walls. Not a place you would stop a train if you were worried about a bomb exploding. It soon became obvious, as the thousand protesters opened their luggage for the RCMP search in the wet November snow, that it was not a bomb they were looking for but weapons. That is how edgy many in the country were getting as the train wound its way east through the Laurentian Shield.

Many, but not all. Some Canadians, such as Ottawa mayor Marion Dewar, hoped that the Indians would be able to stop Trudeau’s unilateral patriation drive, as the provinces seemed to have failed. While the RCMP were busy fortifying the city, Dewar told the people of Ottawa that the B.C. Indians were on their way and they should open their hearts and their homes to them.

Before the train pulled into the Ottawa station, the Constitution Express had already begun to have a political effect. The House of Commons committee studying Trudeau’s legislation had been scheduled to end its hearings that week, but it decided, when the train was just a couple of hundred kilometres from Ottawa, to extend the hearings to give the B.C. Indians an opportunity to have their say.

At the time, I was living in Ottawa doing contract work, sharing an apartment with my friend Dave Monture. For me, the Constitution Express was not only a major political event that shook the city, but also something of a family reunion. My father, who was having health problems at that time, had not taken the train. He had arrived in Ottawa a few days earlier as part of the advance team, and after making a fiery speech at the All Chiefs meeting that was being held in Ottawa to coincide with the Express, he felt ill and was taken to Ottawa General Hospital. It turned out he had had a heart attack, his second. It was a symptom of the slowly progressing heart disease that would continue to weaken his body over the coming years.

My father was forced to follow the Constitution Express from his Ottawa hospital room. But along with Bobby, my wife, Beverly, was on the train with the twins, Mandy and Niki, and our four-month-old son, Neskie.

When I arrived early to meet the train, I was surprised to find a thousand people, many of them Indians from the All Chiefs meeting, already jammed into the station to greet the B.C. protesters. Indian Affairs Minister John Munro was also there, standing with Del Riley, the man who had beaten Bobby for the national chief’s job a few months earlier. Del did not look particularly happy. I had heard that at the National Indian Brotherhood, they were peeved that the Manuels were storming into town with the B.C. Indians and stealing their thunder in the anti-patriation fight. These men were, after all, politicians, so we all understood their concerns.

As the train pulled in, the atmosphere was electric. There were drummers and singers gathered to greet the B.C. Indians, and more drummers and singers coming off the train. The station throbbed with Indian music and with the excitement of the arriving protesters. It took me a while to find Beverly and the kids in the crowd. When I finally spotted them, I could see Beverly was exhausted but joyful.

When Bobby got off the train, he was met by a couple of the B.C. Union advance men who told him, shouting in his ear above the noise of the drumming, that Mayor Dewar had installed a set-up for a quick press statement. They led him away, passing close by John Munro and Del Riley, but Bobby didn’t glance at them. When he reached the microphone, he didn’t mince words.

Bobby denounced the Trudeau constitutional moves as a direct attack on our people. He said they were part of Trudeau’s vision to steal Indian people’s homelands and leave them to end up in the slums of the cities. He concluded by warning that if the government did not include recognition of Aboriginal title and rights in the constitution, the Constitution Express activists “would not only head to New York to protest at the United Nations, they would begin working toward establishing a seat there.”

Then the Constitution Express organizational team went into action, assigning everyone billets and matching them with those who’d offered places to stay. I was enormously impressed by the way people had responded to Mayor Dewar’s call. When the advance team had arrived in Ottawa, they had only a few dozen billets. Dewar put her city team behind the search for accommodation, and by the time the train reached the station, there were not enough Indians to go around to meet the offers. We should have a special place of honour to acknowledge those like Mayor Dewar who stand by us in our hour of need.

While the others were heading to their lodgings to rest after the four-day journey, Bobby led a smaller group to Rideau Hall to deliver a petition to the Governor General, as the Queen’s representative. It stated: “The Creator has given us the right to govern ourselves and the right to self determination. The rights and responsibilities given us by the Creator cannot be altered or taken away by any other nation.”

The petition asked that “Her Majesty refuse the Patriation of the Canadian Constitution until agreement with the Indian Nations is reached.” It also asked the Crown to enter into internationally supervised trilateral negotiations to decide the issue and “to separate Indian nations permanently from the jurisdiction and control of the Government of Canada whose intentions are hostile to our people.”19

There had been a plan for Bobby’s delegation to take over Rideau Hall and hold their own constitutional hearings for a couple of days, but at the last minute, Bobby decided against it. He was criticized by some within the movement at the time, but in retrospect, the takeover wasn’t really needed.

Over the next several days, our people protested passionately on Parliament Hill. They sang, they chanted, they burned sweetgrass, and they spoke with journalists about the threat that the patriation package presented to our rights as Indigenous peoples. The B.C. Union had done its job well. The protesters were the most eloquent spokespeople imaginable for our cause. They had the grassroots passion and—through the Union workshops before and during the cross-country trip—a deep understanding of how the Trudeau constitutional power play could affect their future.

Their message was getting through to the government and to the Canadian people. In the press, the worried chatter about possible violence in the days before train’s arrival was replaced with increasingly positive coverage. More and more voices in Canada were speaking up to support our cause. Finally, a few days after the protesters arrived in the capital, they had their first big victory. Under pressure from his supporters, party leader Ed Broadbent withdrew the New Democratic Party’s support for the constitutional deal until Aboriginal people were included. The Trudeau alliance was cracking, and Trudeau knew that the British would be far less likely to agree to unilateral patriation if it was the request of a single party in the Canadian House of Commons.

Jean Chrétien, now minister of justice and Trudeau’s point man on the constitution, was sent scrambling to get a deal, of any kind, with the Indians, any Indians. He quickly patched together a couple of clauses that, he said, would ensure that the Indians would not lose anything under the charter of rights and freedoms. Del Riley quickly accepted the offer on behalf of the NIB. But the politics had already moved beyond Riley and the National Indian Brotherhood. My father and the Constitution Express protesters were demanding far more. The constitution could not simply skirt around our rights; it had to recognize and affirm them. The NIB was pushed back onto the sidelines as the Constitution Express continued to dominate Ottawa, and sent a delegation to New York to protest at the United Nations with the support of American Indians.

But the Union continued to direct its main attention to England, where the National Indian Brotherhood had had an active lobby since 1979. Our people understood that ultimately it was a British wrong that had robbed of us our powers in the BNA Act, and it was their responsibility to right it. In Ottawa, the Union sent a message directly to the British:

We have our own relationship with the British Parliament—a relationship which places a constitutional duty upon the British Parliament to ensure that our rights and interests are protected and that Crown obligations to us continue with the passage of time, until we achieve self determination. The Indian Nations are calling upon the British Parliament to perform their duty to us by refusing to patriate the Canadian constitution until it can be done without prejudice to Crown obligations and until the supervisory jurisdiction presently vested in the British Parliament be vested in the Indian Nations and not in the Federal or Provincial legislatures.20

The Union message and the message of the previous NIB lobbying were finally received. While the Constitution Express was still in Ottawa, the British parliamentary committee responsible for passing the patriation legislation fired a warning shot across the Trudeau government’s bow. On December 5, the British announced that there would be no quick passage of the bill on their side. They would not move on it until June 1981, at the earliest.

With dwindling support at home and with the British signalling that they would not be rushed into granting the Trudeau government quick passage while the move was so controversial in Canada, the unilateral patriation drive was effectively stalled. Prime Minister Trudeau extended the deadline for the House of Commons Constitutional Committee report. He would have to go back to the provinces and to Aboriginal people to get a deal.

From his hospital bed in Ottawa, my father felt the tide turning. Doctors and nurses and hospital visitors poked their heads into his room to offer encouragement and to let him know they were impressed by the passion and discipline of the protesters on Parliament Hill. Describing his time at the hospital, he told his supporters, “I was treated like a king. That is how much you stimulated Ottawa.”21

This road would have many twists to come. In February 1981, when the Constitutional Committee presented its report, an affirmation of Aboriginal title and rights was included in Section 35. This set off a new round of the battles between our people, who wanted more, and a group of provincial premiers who wanted Aboriginal rights struck from the deal. The B.C. provincial government delegation took the lead in lobbying for the removal of the clause, and they found support among the other Western premiers.

In September, the Supreme Court blocked Trudeau’s patriation drive without “a substantial measure” of provincial government support. The prime minister called a premiers conference, as a last-ditch attempt to strike a constitutional deal, for the first week of November.

The Union decided this time to target British and international opinion directly and make the Indian voice heard with its European Constitution Express. It was planned for the first week of the premiers meeting. The Union delegation left for Europe on November 1, 1981, with an itinerary that included Netherlands, Germany, France, Belgium, and England. The main destination was London, where the delegation would again attempt to convince the British to refuse patriation without a clear recognition of Indigenous nationhood in the constitution.

Once again, it was a grassroots effort. Because of the cost—$2,500 each for transportation and lodging—participants sought support from their bands. To make the maximum impression, they were told to bring their traditional dress and hand drums, and gifts for their hosts (jewellery, carving, beadwork, and so on). They were also told “bring information on [their] own band or area if possible, for example; pictures on conditions of communities and pictures of various traditional activities like pow-wows, hunting with game, fishing, new houses and old houses, mills or plants close to reserves, forests, construction roadways, or logging.” The instructions to participants also detailed personal goods they could bring through customs in Europe; since it was for B.C. Indians, the list included “1 salmon (FRESH OR SMOKED) Per Person or six tins of 4 ounces salmon.”22

It is important to stress that, just like on the Canadian Constitution Express, the great majority of the people travelling were not leaders or experts but grassroots people. As the Union historian of the period put it:

The Union, under the leadership of George Manuel sent the Constitutional Express to Europe. The UBCIC brought the voices of the people in the communities throughout the country to the international arena and made it clear that the aboriginal people of Canada would not stand back and allow their rights to be infringed upon.

The excellent organization, forethought and vision of the Constitutional Express not only raised the consciousness of the public but also brought back the pride of the aboriginal peoples and the strength which has always been needed to fight for the recognition, the survival and the promotion of our rights.23

While the flights were leaving Vancouver, the premiers were landing in Ottawa to hammer out a constitutional deal. After days of deadlock, nine of the ten premiers reached a backroom deal with Chrétien, in what is widely known as the Night of the Long Knives when Quebec premier René Lévesque was stabbed in the back by the other premiers.

But the knife that night was used first against our people. In his account of the evening, lead B.C. negotiator Mel Smith wrote that some of the other provinces were worried about what effect Aboriginal rights would have on their jurisdiction. Others said it was Smith who expressed “strong reservations because almost none of British Columbia had been ceded by the Indians to the province through treaties. There was an uncertainty about the legal effect of this historical fact; the other provinces reluctantly acquiesced to this argument.”24 So in the middle of night, Aboriginal people were tossed out of constitution, along with Quebec.

In Britain, the presence of the European Express guaranteed extra coverage for the new betrayal of Canada’s Indigenous peoples, and once again, British press and parliamentarians began to urge that the Thatcher government refuse patriation under such contested conditions within Canada. When the Trudeau government listened to the Western premiers and presented its final package, without protection for Aboriginal people, it was met with a storm of protest so strong that the premiers themselves were forced to begin a series of conference calls that ended with Section 35 being reinstated.

The result was that Section 91(24) of the BNA Act, which gave the federal government sole responsibility over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians,” would now be framed by Section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982: “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

In the BNA Act, only two entities were recognized in the Constitution—the federal government in the list of Section 91 powers and the provinces in the list of Section 92 powers. These seventeen words in Section 35 announced a new entity in the Canadian power structure: Aboriginal peoples, whose own constitutionally recognized rights would be “recognized and affirmed.”

Those who hoped that we had finally reached open water were soon disappointed, however. It is impossible to underestimate the depth and intransigence of the colonial mindset in Canada. While legal recognition of our rights was provided in the fundamental law of the land, political recognition would not be forthcoming.

This political dimension was supposed to be resolved in the series of First Nations/federal and provincial conferences that were mandated in the 1982 Constitution. Meetings to define our self-governing rights were held in 1983, 1984, 1985, and 1987. But each of these constitutional conferences ended in failure. There were some very modest changes to the wording of the subsections of Section 35 but no substantial movement to recognize our new constitutional status at a political level. Despite the promise to “recognize and affirm,” it soon became clear that the approach of the federal and many of the provincial governments would be better summed up as to “ignore and deny.” It would only be years later, when the courts finally stepped in again, that real weight would be given to Section 35.

The constitutional battle was a roller coaster ride for our people, but it also provided a model for Indigenous struggle. The main reason it was effective in having our rights recognized in the Constitution was that it focused on mass mobilization of the people rather than on leaders pleading their case in committee rooms or behind closed doors with government officials. Throughout this battle, the B.C. Union leadership had numerous invitations to appear before government committees to plead their case, but they refused the offers. They understood that we needed a much wider playing field.

We need to get outside the narrow bounds of parliamentary procedure and official negotiating tables, and demand our rights with a show of strength. Governments are not moved to listen by arguments or pleas for justice from our leadership. These rain on them at all times and governments are oblivious to them. What moved the government and the people of Canada was the passion and power of our people unified at the grassroots level, demanding justice for themselves and their children. The Constitution Express turned the patriation from a serious threat to an important gain for us that we can continue to build on into the future.

This is what our people accomplished by determined action together. And these are the means by which we can make continued advances today.