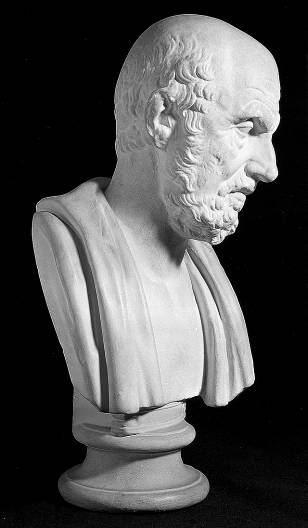

The Complete Works of

HIPPOCRATES

(c. 460 – c. 370 BC)

Contents

ON THE INSTRUMENTS OF REDUCTION

Works of the Hippocratic Corpus

GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO HIPPOCRATES by W. H. S. Jones

© Delphi Classics 2015

Version 1

The Complete Works of

HIPPOCRATES

By Delphi Classics, 2015

Complete Works of Hippocrates

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

Harbour of Cos (ancient Kos) — Hippocrates’ birthplace

![]()

OR, TRADITION IN MEDICINE

Translated by Charles Darwin Adams

This treatise is regarded as one of the most significant works of the Hippocratic Corpus, the collection of approximately sixty writings covering all areas of medical thought and practice, which are traditionally associated with Hippocrates (c. 460 BC – c. 370 BC), the father of Western medicine. In more recent times, thirteen of the works have been identified as being possibly by the hand of Hippocrates, with On Ancient Medicine being a key text of this number. The origins of the Hippocratic Corpus can be traced to the sixth and fifth centuries BC in Italy.

There were two seminal schools of Western medical thought; Agrigentum on the southern coast of Sicily and Croton on the west coast of the Gulf of Taranto. Agrigentum was the home of Empedocles, while Croton belonged to the Pythagorean sect of medical philosophy. The school of Agrigentum and Empedocles placed great emphasis on cure by contraries, while the school of Croton rejected this notion, championing the medical philosophy that perceived the human organism consists of an infinite number of humours. The first medical philosopher of the school of Croton was Alcmaeon, who argued that the maintenance of good health required a balance of the powers of moist and dry, cold and hot, bitter and sweet. He argued that sickness arises when there is an imbalance within the human organism, caused by the predominance of one power over another. In the Agrigentum school of thought Empedocles hypothesised that the universe consisted of four elements: earth, water, air and fire. On the basis of these four elements he sought to account for the origin of matter. Matter or the universe was generated out of these four elements and their mutual attraction and repulsion.

The conflict between these two schools of thought became manifest in their medical philosophies. Whereas, Alcmaeon argued that there were indefinite number of diverse qualities that made up the human organism, Empedocles believed that there were four concrete or substantial elements. Although it is Empedocles’ medical philosophy that ultimately inspires the humoral doctrine of human nature, it is Alcmaeon’s theory that provides the backdrop to the medical therapeutic doctrine proposed in On Ancient Medicine . Alcmaeon’s argument that there are an infinite number of causes for disease that cannot be simply organised into categories is the basic operating assumption of empirical medicine. Therefore medical knowledge continuously expanded thorough a firsthand experience and observation of the human organism within nature. It is in this light that On Ancient Medicine should be seen as an attempt by Alcmaeon’s followers and the empirical school of thought to respond to and critique the Empedoclean or humoral theory of medicine.

On Ancient Medicine is formed of three parts. In chapters 1–19 the author responds to the supporters of the hypothesis theory of medicine, arguing that the exploration of medicine itself reveals the human organism as a blend of diverse substances or humours. Having set forth this humoral theory, he then critiques the hypothesis theory proposed by his opponents as being an oversimplified conception of the cause of disease. He then discusses his own theory and method employed in its discovery (chapters 20-24), before responding to the charge that ancient medicine is not a genuine medical art because it has limited accuracy. These arguments must be seen in the light of the author’s theory of human physiology (chapters 9-12).

It is generally believed that On Ancient Medicine was written between 440 and 350 BC, with several hints suggesting a date in the late fifth century. In particular, the author refers to Empedocles (490–430 B.C.) as the motivation of the method he attacks, which would suggest a date not long after Empedocles’ peak of activity.

Since the work of Émile Littré in the nineteenth century, the treatise has been scrutinised in thorough detail, in an attempt to determine which of the works in the Hippocratic Corpus were composed by Hippocrates. Littré was the scholar most associated with advocating that On Ancient Medicine was written by Hippocrates, as he believed that it was the work to which Plato was referring to in The Phaedrus . However, it is difficult to establish any certainty as to whether the historical Hippocrates actually wrote the treatise On Ancient Medicine , due to the scanty surviving evidence from references in Plato and Aristotle.

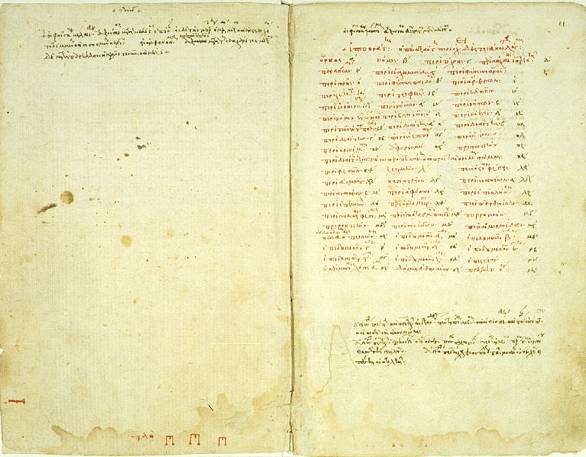

Vaticanus graecus 277, 10v-11r — a fourteenth century Hippocratic Corpus manuscript.

ON ANCIENT MEDICINE

1. Whoever having undertaken to speak or write on Medicine, have first laid down for themselves some hypothesis to their argument, such as hot, or cold, or moist, or dry, or whatever else they choose (thus reducing their subject within a narrow compass, and supposing only one or two original causes of diseases or of death among mankind), are all clearly mistaken in much that they say; and this is the more reprehensible as relating to an art which all men avail themselves of on the most important occasions, and the good operators and practitioners in which they hold in especial honor. For there are practitioners, some bad and some far otherwise, which, if there had been no such thing as Medicine, and if nothing had been investigated or found out in it, would not have been the case, but all would have been equally unskilled and ignorant of it, and everything concerning the sick would have been directed by chance. But now it is not so; for, as in all the other arts, those who practise them differ much from one another in dexterity and knowledge, so is it in like manner with Medicine. Wherefore I have not thought that it stood in need of an empty hypothesis, like those subjects which are occult and dubious, in attempting to handle which it is necessary to use some hypothesis; as, for example, with regard to things above us and things below the earth; if any one should treat of these and undertake to declare how they are constituted, the reader or hearer could not find out, whether what is delivered be true or false; for there is nothing which can be referred to in order to discover the truth.

2. But all these requisites belong of old to Medicine, and an origin and way have been found out, by which many and elegant discoveries have been made, during a length of time, and others will yet be found out, if a person possessed of the proper ability, and knowing those discoveries which have been made, should proceed from them to prosecute his investigations. But whoever, rejecting and despising all these, attempts to pursue another course and form of inquiry, and says he has discovered anything, is deceived himself and deceives others, for the thing is impossible. And for what reason it is impossible, I will now endeavor to explain, by stating and showing what the art really is. From this it will be manifest that discoveries cannot possibly be made in any other way. And most especially, it appears to me, that whoever treats of this art should treat of things which are familiar to the common people. For of nothing else will such a one have to inquire or treat, but of the diseases under which the common people have labored, which diseases and the causes of their origin and departure, their increase and decline, illiterate persons cannot easily find out themselves, but still it is easy for them to understand these things when discovered and expounded by others. For it is nothing more than that every one is put in mind of what had occurred to himself. But whoever does not reach the capacity of the illiterate vulgar and fails to make them listen to him, misses his mark. Wherefore, then, there is no necessity for any hypothesis.

3. For the art of Medicine would not have been invented at first, nor would it have been made a subject of investigation (for there would have been no need of it), if when men are indisposed, the same food and other articles of regimen which they eat and drink when in good health were proper for them, and if no others were preferable to these. But now necessity itself made medicine to be sought out and discovered by men, since the same things when administered to the sick, which agreed with them when in good health, neither did nor do agree with them. But to go still further back, I hold that the diet and food which people in health now use would not have been discovered, provided it had suited with man to eat and drink in like manner as the ox, the horse, and all other animals, except man, do of the productions of the earth, such as fruits, weeds, and grass; for from such things these animals grow, live free of disease, and require no other kind of food. And, at first, I am of opinion that man used the same sort of food, and that the present articles of diet had been discovered and invented only after a long lapse of time, for when they suffered much and severely from strong and brutish diet, swallowing things which were raw, unmixed, and possessing great strength, they became exposed to strong pains and diseases, and to early deaths. It is likely, indeed, that from habit they would suffer less from these things then than we would now, but still they would suffer severely even then; and it is likely that the greater number, and those who had weaker constitutions, would all perish; whereas the stronger would hold out for a longer time, as even nowadays some, in consequence of using strong articles of food, get off with little trouble, but others with much pain and suffering. From this necessity it appears to me that they would search out the food befitting their nature, and thus discover that which we now use: and that from wheat, by macerating it, stripping it of its hull, grinding it all down, sifting, toasting, and baking it, they formed bread; and from barley they formed cake (maza), performing many operations in regard to it; they boiled, they roasted, they mixed, they diluted those things which are strong and of intense qualities with weaker things, fashioning them to the nature and powers of man, and considering that the stronger things Nature would not be able to manage if administered, and that from such things pains, diseases, and death would arise, but such as Nature could manage, that from them food, growth, and health, would arise. To such a discovery and investigation what more suitable name could one give than that of Medicine? since it was discovered for the health of man, for his nourishment and safety, as a substitute for that kind of diet by which pains, diseases, and deaths were occasioned.

4. And if this is not held to be an art, I do not object. For it is not suitable to call any one an artist of that which no one is ignorant of, but which all know from usage and necessity. But still the discovery is a great one, and requiring much art and investigation. Wherefore those who devote themselves to gymnastics and training, are always making some new discovery, by pursuing the same line of inquiry, where, by eating and drinking certain things, they are improved and grow stronger than they were.

5. Let us inquire then regarding what is admitted to be Medicine; namely, that which was invented for the sake of the sick, which possesses a name and practitioners, whether it also seeks to accomplish the same objects, and whence it derived its origin. To me, then, it appears, as I said at the commencement, that nobody would have sought for medicine at all, provided the same kinds of diet had suited with men in sickness as in good health. Wherefore, even yet, such races of men as make no use of medicine, namely, barbarians, and even certain of the Greeks, live in the same way when sick as when in health; that is to say, they take what suits their appetite, and neither abstain from, nor restrict themselves in anything for which they have a desire. But those who have cultivated and invented medicine, having the same object in view as those of whom I formerly spoke, in the first place, I suppose, diminished the quantity of the articles of food which they used, and this alone would be sufficient for certain of the sick, and be manifestly beneficial to them, although not to all, for there would be some so affected as not to be able to manage even small quantities of their usual food, and as such persons would seem to require something weaker, they invented soups, by mixing a few strong things with much water, and thus abstracting that which was strong in them by dilution and boiling. But such as could not manage even soups, laid them aside, and had recourse to drinks, and so regulated them as to mixture and quantity, that they were administered neither stronger nor weaker than what was required.

6. But this ought to be well known, that soups do not agree with certain persons in their diseases, but, on the contrary, when administered both the fevers and the pains are exacerbated, and it becomes obvious that what was given has proved food and increase to the disease, but a wasting and weakness to the body. But whatever persons so affected partook of solid food, or cake, or bread, even in small quantity, would be ten times and more decidedly injured than those who had taken soups, for no other reason than from the strength of the food in reference to the affection; and to whomsoever it is proper to take soups and not eat solid food, such a one will be much more injured if he eat much than if he eat little, but even little food will be injurious to him. But all the causes of the sufferance refer themselves to this rule, that the strongest things most especially and decidedly hurt man, whether in health or in disease.

7. What other object, then, had he in view who is called a physician, and is admitted to be a practitioner of the art, who found out the regimen and diet befitting the sick, than he who originally found out and prepared for all mankind that kind of food which we all now use, in place of the former savage and brutish mode of living? To me it appears that the mode is the same, and the discovery of a similar nature. The one sought to abstract those things which the constitution of man cannot digest, because of their wildness and intemperature, and the other those things which are beyond the powers of the affection in which any one may happen to be laid up. Now, how does the one differ from the other, except that the latter admits of greater variety, and requires more application, whereas the former was the commencement of the process?

8. And if one would compare the diet of sick persons with that of persons in health, he will find it not more injurious than that of healthy persons in comparison with that of wild beasts and of other animals. For, suppose a man laboring under one of those diseases which are neither serious and unsupportable, nor yet altogether mild, but such as that, upon making any mistake in diet, it will become apparent, as if he should eat bread and flesh, or any other of those articles which prove beneficial to healthy persons, and that, too, not in great quantity, but much less than he could have taken when in good health; and that another man in good health, having a constitution neither very feeble, nor yet strong, eats of those things which are wholesome and strengthening to an ox or a horse, such as vetches, barley, and the like, and that, too, not in great quantity, but much less than he could take; the healthy person who did so would be subjected to no less disturbance and danger than the sick person who took bread or cake unseasonably. All these things are proofs that Medicine is to be prosecuted and discovered by the same method as the other.

9. And if it were simply, as is laid down, that such things as are stronger prove injurious, but such as are weaker prove beneficial and nourishing, both to sick and healthy persons, it were an easy matter, for then the safest rule would be to circumscribe the diet to the lowest point. But then it is no less mistake, nor one that injuries a man less, provided a deficient diet, or one consisting of weaker things than what are proper, be administered. For, in the constitution of man, abstinence may enervate, weaken, and kill. And there are many other ills, different from those of repletion, but no less dreadful, arising from deficiency of food; wherefore the practice in those cases is more varied, and requires greater accuracy. For one must aim at attaining a certain measure, and yet this measure admits neither weight nor calculation of any kind, by which it may be accurately determined, unless it be the sensation of the body; wherefore it is a task to learn this accurately, so as not to commit small blunders either on the one side or the other, and in fact I would give great praise to the physician whose mistakes are small, for perfect accuracy is seldom to be seen, since many physicians seem to me to be in the same plight as bad pilots, who, if they commit mistakes while conducting the ship in a calm do not expose themselves, but when a storm and violent hurricane overtake them, they then, from their ignorance and mistakes, are discovered to be what they are, by all men, namely, in losing their ship. And thus bad and commonplace physicians, when they treat men who have no serious illness, in which case one may commit great mistakes without producing any formidable mischief (and such complaints occur much more frequently to men than dangerous ones): under these circumstances, when they commit mistakes, they do not expose themselves to ordinary men; but when they fall in with a great, a strong, and a dangerous disease, then their mistakes and want of skill are made apparent to all. Their punishment is not far off, but is swift in overtaking both the one and the other.

10. And that no less mischief happens to a man from unseasonable depletion than from repletion, may be clearly seen upon reverting to the consideration of persons in health. For, to some, with whom it agrees to take only one meal in the day, and they have arranged it so accordingly; whilst others, for the same reason, also take dinner, and this they do because they find it good for them, and not like those persons who, for pleasure or from any casual circumstance, adopt the one or the other custom and to the bulk of mankind it is of little consequence which of these rules they observe, that is to say, whether they make it a practice to take one or two meals. But there are certain persons who cannot readily change their diet with impunity; and if they make any alteration in it for one day, or even for a part of a day, are greatly injured thereby. Such persons, provided they take dinner when it is not their wont, immediately become heavy and inactive, both in body and mind, and are weighed down with yawning, slumbering, and thirst; and if they take supper in addition, they are seized with flatulence, tormina, and diarrhea, and to many this has been the commencement of a serious disease, when they have merely taken twice in a day the same food which they have been in the custom of taking once. And thus, also, if one who has been accustomed to dine, and this rule agrees with him, should not dine at the accustomed hour, he will straightway feel great loss of strength, trembling, and want of spirits, the eyes of such a person will become more pallid, his urine thick and hot, his mouth bitter; his bowels will seem, as it were, to hang loose; he will suffer from vertigo, lowness of spirit, and inactivity,- such are the effects; and if he should attempt to take at supper the same food which he was wont to partake of at dinner, it will appear insipid, and he will not be able to take it off; and these things, passing downwards with tormina and rumbling, burn up his bowels; he experiences insomnolency or troubled and disturbed dreams; and to many of them these symptoms are the commencement of some disease.

11. But let us inquire what are the causes of these things which happened to them. To him, then, who was accustomed to take only one meal in the day, they happened because he did not wait the proper time, until his bowels had completely derived benefit from and had digested the articles taken at the preceding meal, and until his belly had become soft, and got into a state of rest, but he gave it a new supply while in a state of heat and fermentation, for such bellies digest much more slowly, and require more rest and ease. And as to him who had been accustomed to dinner, since, as soon as the body required food, and when the former meal was consumed, and he wanted refreshment, no new supply was furnished to it, he wastes and is consumed from want of food. For all the symptoms which I describe as befalling to this man I refer to want of food. And I also say that all men who, when in a state of health, remain for two or three days without food, experience the same unpleasant symptoms as those which I described in the case of him who had omitted to take dinner.

12. Wherefore, I say, that such constitutions as suffer quickly and strongly from errors in diet, are weaker than others that do not; and that a weak person is in a state very nearly approaching to one in disease; but a person in disease is the weaker, and it is, therefore, more likely that he should suffer if he encounters anything that is unseasonable. It is difficult, seeing that there is no such accuracy in the Art, to hit always upon what is most expedient, and yet many cases occur in medicine which would require this accuracy, as we shall explain. But on that account, I say, we ought not to reject the ancient Art, as if it were not, and had not been properly founded, because it did not attain accuracy in all things, but rather, since it is capable of reaching to the greatest exactitude by reasoning, to receive it and admire its discoveries, made from a state of great ignorance, and as having been well and properly made, and not from chance.

13. But I wish the discourse to revert to the new method of those who prosecute their inquiries in the Art by hypothesis. For if hot, or cold, or moist, or dry, be that which proves injurious to man, and if the person who would treat him properly must apply cold to the hot, hot to the cold, moist to the dry, and dry to the moist- let me be presented with a man, not indeed one of a strong constitution, but one of the weaker, and let him eat wheat, such as it is supplied from the thrashing-floor, raw and unprepared, with raw meat, and let him drink water. By using such a diet I know that he will suffer much and severely, for he will experience pains, his body will become weak, and his bowels deranged, and he will not subsist long. What remedy, then, is to be provided for one so situated? Hot? or cold? or moist? or dry? For it is clear that it must be one or other of these. For, according to this principle, if it is one of the which is injuring the patient, it is to be removed by its contrary. But the surest and most obvious remedy is to change the diet which the person used, and instead of wheat to give bread, and instead of raw flesh, boiled, and to drink wine in addition to these; for by making these changes it is impossible but that he must get better, unless completely disorganized by time and diet. What, then, shall we say? whether that, as he suffered from cold, these hot things being applied were of use to him, or the contrary? I should think this question must prove a puzzler to whomsoever it is put. For whether did he who prepared bread out of wheat remove the hot, the cold, the moist, or the dry principle in it?- for the bread is consigned both to fire and to water, and is wrought with many things, each of which has its peculiar property and nature, some of which it loses, and with others it is diluted and mixed.

14. And this I know, moreover, that to the human body it makes a great difference whether the bread be fine or coarse; of wheat with or without the hull, whether mixed with much or little water, strongly wrought or scarcely at all, baked or raw- and a multitude of similar differences; and so, in like manner, with the cake (maza); the powers of each, too, are great, and the one nowise like the other. Whoever pays no attention to these things, or, paying attention, does not comprehend them, how can he understand the diseases which befall a man? For, by every one of these things, a man is affected and changed this way or that, and the whole of his life is subjected to them, whether in health, convalescence, or disease. Nothing else, then, can be more important or more necessary to know than these things. So that the first inventors, pursuing their investigations properly, and by a suitable train of reasoning, according to the nature of man, made their discoveries, and thought the Art worthy of being ascribed to a god, as is the established belief. For they did not suppose that the dry or the moist, the hot or the cold, or any of these are either injurious to man, or that man stands in need of them, but whatever in each was strong, and more than a match for a man’s constitution, whatever he could not manage, that they held to be hurtful, and sought to remove. Now, of the sweet, the strongest is that which is intensely sweet; of the bitter, that which is intensely bitter; of the acid, that which is intensely acid; and of all things that which is extreme, for these things they saw both existing in man, and proving injurious to him. For there is in man the bitter and the salt, the sweet and the acid, the sour and the insipid, and a multitude of other things having all sorts of powers both as regards quantity and strength. These, when all mixed and mingled up with one another, are not apparent, neither do they hurt a man; but when any of them is separate, and stands by itself, then it becomes perceptible, and hurts a man. And thus, of articles of food, those which are unsuitable and hurtful to man when administered, every one is either bitter, or intensely so, or saltish or acid, or something else intense and strong, and therefore we are disordered by them in like manner as we are by the secretions in the body. But all those things which a man eats and drinks are devoid of any such intense and well-marked quality, such as bread, cake, and many other things of a similar nature which man is accustomed to use for food, with the exception of condiments and confectioneries, which are made to gratify the palate and for luxury. And from those things, when received into the body abundantly, there is no disorder nor dissolution of the powers belonging to the body; but strength, growth, and nourishment result from them, and this for no other reason than because they are well mixed, have nothing in them of an immoderate character, nor anything strong, but the whole forms one simple and not strong substance.

15. I cannot think in what manner they who advance this doctrine, and transfer Art from the cause I have described to hypothesis, will cure men according to the principle which they have laid down. For, as far as I know, neither the hot nor the cold, nor the dry, nor the moist, has ever been found unmixed with any other quality; but I suppose they use the same articles of meat and drink as all we other men do. But to this substance they give the attribute of being hot, to that cold, to that dry, and to that moist. Since it would be absurd to advise the patient to take something hot, for he would straightway ask what it is? so that he must either play the fool, or have recourse to some one of the well known substances; and if this hot thing happen to be sour, and that hot thing insipid, and this hot thing has the power of raising a disturbance in the body (and there are many other kinds of heat, possessing many opposite powers), he will be obliged to administer some one of them, either the hot and the sour, or the hot and the insipid, or that which, at the same time, is cold and sour (for there is such a substance), or the cold and the insipid. For, as I think, the very opposite effects will result from either of these, not only in man, but also in a bladder, a vessel of wood, and in many other things possessed of far less sensibility than man; for it is not the heat which is possessed of great efficacy, but the sour and the insipid, and other qualities as described by me, both in man and out of man, and that whether eaten or drunk, rubbed in externally, and otherwise applied.

16. But I think that of all the qualities heat and cold exercise the least operation in the body, for these reasons: as long time as hot and cold are mixed up with one another they do not give trouble, for the cold is attempered and rendered more moderate by the hot, and the hot by the cold; but when the one is wholly separate from the other, then it gives pain; and at that season when cold is applied it creates some pain to a man, but quickly, for that very reason, heat spontaneously arises in him without requiring any aid or preparation. And these things operate thus both upon men in health and in disease. For example, if a person in health wishes to cool his body during winter, and bathes either in cold water or in any other way, the more he does this, unless his body be fairly congealed, when he resumes his clothes and comes into a place of shelter, his body becomes more heated than before. And thus, too, if a person wish to be warmed thoroughly either by means of a hot bath or strong fire, and straight-way having the same clothing on, takes up his abode again in the place he was in when he became congealed, he will appear much colder, and more disposed to chills than before. And if a person fan himself on account of a suffocating heat, and having procured refrigeration for himself in this manner, cease doing so, the heat and suffocation will be ten times greater in his case than in that of a person who does nothing of the kind. And, to give a more striking example, persons travelling in the snow, or otherwise in rigorous weather, and contracting great cold in their feet, their hands, or their head, what do they not suffer from inflammation and tingling when they put on warm clothing and get into a hot place? In some instances, blisters arise as if from burning with fire, and they do not suffer from any of those unpleasant symptoms until they become heated. So readily does either of these pass into the other; and I could mention many other examples. And with regard to the sick, is it not in those who experience a rigor that the most acute fever is apt to break out? And yet not so strongly neither, but that it ceases in a short time, and, for the most part, without having occasioned much mischief; and while it remains, it is hot, and passing over the whole body, ends for the most part in the feet, where the chills and cold were most intense and lasted longest; and, when sweat supervenes, and the fever passes off, the patient is much colder than if he had not taken the fever at all. Why then should that which so quickly passes into the opposite extreme, and loses its own powers spontaneously, be reckoned a mighty and serious affair? And what necessity is there for any great remedy for it?

17. One might here say- but persons in ardent fevers, pneumonia, and other formidable diseases, do not quickly get rid of the heat, nor experience these rapid alterations of heat and cold. And I reckon this very circumstance the strongest proof that it is not from heat simply that men get into the febrile state, neither is it the sole cause of the mischief, but that this species of heat is bitter, and that acid, and the other saltish, and many other varieties; and again there is cold combined with other qualities. These are what proves injurious; heat, it is true, is present also, possessed of strength as being that which conducts, is exacerbated and increased along with the other, but has no power greater than what is peculiar to itself.

18. With regard to these symptoms, in the first place those are most obvious of which we have all often had experience. Thus, then, in such of us as have a coryza and defluxion from the nostrils, this discharge is much more acrid than that which formerly was formed in and ran from them daily; and it occasions swelling of the nose, and it inflames, being of a hot and extremely ardent nature, as you may know, if you apply your hand to the place; and, if the disease remains long, the part becomes ulcerated although destitute of flesh and hard; and the heat in the nose ceases, not when the defluxion takes place and the inflammation is present, but when the running becomes thicker and less acrid, and more mixed with the former secretion, then it is that the heat ceases. But in all those cases in which this decidedly proceeds from cold alone, without the concourse of any other quality, there is a change from cold to hot, and from hot to cold, and these quickly supervene, and require no coction. But all the others being connected, as I have said, with acrimony and intemperance of humors, pass off in this way by being mixed and concocted.

19. But such defluxions as are determined to the eyes being possessed of strong and varied acrimonies, ulcerate the eyelids, and in some cases corrode the and parts below the eyes upon which they flow, and even occasion rupture and erosion of the tunic which surrounds the eyeball. But pain, heat, and extreme burning prevail until the defluxions are concocted and become thicker, and concretions form about the eyes, and the coction takes place from the fluids being mixed up, diluted, and digested together. And in defluxions upon the throat, from which are formed hoarseness, cynanche, crysipelas, and pneumonia, all these have at first saltish, watery, and acrid discharges, and with these the diseases gain strength. But when the discharges become thicker, more concocted, and are freed from all acrimony, then, indeed, the fevers pass away, and the other symptoms which annoyed the patient; for we must account those things the cause of each complaint, which, being present in a certain fashion, the complaint exists, but it ceases when they change to another combination. But those which originate from pure heat or cold, and do not participate in any other quality, will then cease when they undergo a change from cold to hot, and from hot to cold; and they change in the manner I have described before. Wherefore, all the other complaints to which man is subject arise from powers (qualities?). Thus, when there is an overflow of the bitter principle, which we call yellow bile, what anxiety, burning heat, and loss of strength prevail! but if relieved from it, either by being purged spontaneously, or by means of a medicine seasonably administered, the patient is decidedly relieved of the pains and heat; but while these things float on the stomach, unconcocted and undigested, no contrivance could make the pains and fever cease; and when there are acidities of an acrid and aeruginous character, what varieties of frenzy, gnawing pains in the bowels and chest, and inquietude, prevail! and these do not cease until the acidities be purged away, or are calmed down and mixed with other fluids. The coction, change, attenuation, and thickening into the form of humors, take place through many and various forms; therefore the crises and calculations of time are of great importance in such matters; but to all such changes hot and cold are but little exposed, for these are neither liable to putrefaction nor thickening. What then shall we say of the change? that it is a combination (crasis) of these humors having different powers toward one another. But the hot does not loose its heat when mixed with any other thing except the cold; nor again, the cold, except when mixed with the hot. But all other things connected with man become the more mild and better in proportion as they are mixed with the more things besides. But a man is in the best possible state when they are concocted and at rest, exhibiting no one peculiar quality; but I think I have said enough in explanation of them.

20. Certain sophists and physicians say that it is not possible for any one to know medicine who does not know what man is [and how he was made and how constructed], and that whoever would cure men properly, must learn this in the first place. But this saying rather appertains to philosophy, as Empedocles and certain others have described what man in his origin is, and how he first was made and constructed. But I think whatever such has been said or written by sophist or physician concerning nature has less connection with the art of medicine than with the art of painting. And I think that one cannot know anything certain respecting nature from any other quarter than from medicine; and that this knowledge is to be attained when one comprehends the whole subject of medicine properly, but not until then; and I say that this history shows what man is, by what causes he was made, and other things accurately. Wherefore it appears to me necessary to every physician to be skilled in nature, and strive to know, if he would wish to perform his duties, what man is in relation to the articles of food and drink, and to his other occupations, and what are the effects of each of them to every one. And it is not enough to know simply that cheese is a bad article of food, as disagreeing with whoever eats of it to satiety, but what sort of disturbance it creates, and wherefore, and with what principle in man it disagrees; for there are many other articles of food and drink naturally bad which affect man in a different manner. Thus, to illustrate my meaning by an example, undiluted wine drunk in large quantity renders a man feeble; and everybody seeing this knows that such is the power of wine, and the cause thereof; and we know, moreover, on what parts of a man’s body it principally exerts its action; and I wish the same certainty to appear in other cases. For cheese (since we used it as an example) does not prove equally injurious to all men, for there are some who can take it to satiety without being hurt by it in the least, but, on the contrary, it is wonderful what strength it imparts to those it agrees with; but there are some who do not bear it well, their constitutions are different, and they differ in this respect, that what in their body is incompatible with cheese, is roused and put in commotion by such a thing; and those in whose bodies such a humor happens to prevail in greater quantity and intensity, are likely to suffer the more from it. But if the thing had been pernicious to of man, it would have hurt all. Whoever knows these things will not suffer from it.

21. During convalescence from diseases, and also in protracted diseases, many disorders occur, some spontaneously, and some from certain things accidentally administered. I know that the common herd of physicians, like the vulgar, if there happen to have been any innovation made about that day, such as the bath being used, a walk taken, or any unusual food eaten, all which were better done than otherwise, attribute notwithstanding the cause of these disorders, to some of these things, being ignorant of the true cause but proscribing what may have been very proper. Now this ought not to be so; but one should know the effects of a bath or a walk unseasonably applied; for thus there will never be any mischief from these things, nor from any other thing, nor from repletion, nor from such and such an article of food. Whoever does not know what effect these things produce upon a man, cannot know the consequences which result from them, nor how to apply them.

22. And it appears to me that one ought also to know what diseases arise in man from the powers, and what from the structures. What do I mean by this? By powers, I mean intense and strong juices; and by structures, whatever conformations there are in man. For some are hollow, and from broad contracted into narrow; some expanded, some hard and round, some broad and suspended, some stretched, some long, some dense, some rare and succulent, some spongy and of loose texture. Now, then, which of these figures is the best calculated to suck to itself and attract humidity from another body? Whether what is hollow and expanded, or what is solid and round, or what is hollow, and from broad, gradually turning narrow? I think such as from hollow and broad are contracted into narrow: this may be ascertained otherwise from obvious facts: thus, if you gape wide with the mouth you cannot draw in any liquid; but by protruding, contracting, and compressing the lips, and still more by using a tube, you can readily draw in whatever you wish. And thus, too, the instruments which are used for cupping are broad below and gradually become narrow, and are so con-structed in order to suck and draw in from the fleshy parts. The nature and construction of the parts within a man are of a like nature; the bladder, the head, the uterus in woman; these parts clearly attract, and are always filled with a juice which is foreign to them. Those parts which are hollow and expanded are most likely to receive any humidity flowing into them, but cannot attract it in like manner. Those parts which are solid and round could not attract a humidity, nor receive it when it flows to them, for it would glide past, and find no place of rest on them. But spongy and rare parts, such as the spleen, the lungs, and the breasts, drink up especially the juices around them, and become hardened and enlarged by the accession of juices. Such things happen to these organs especially. For it is not with the spleen as with the stomach, in which there is a liquid, which it contains and evacuates every day; but when it (the spleen) drinks up and receives a fluid into itself, the hollow and lax parts of it are filled, even the small interstices; and, instead of being rare and soft, it becomes hard and dense, and it can neither digest nor discharge its contents: these things it suffers, owing to the nature of its structure. Those things which engender flatulence or tormina in the body, naturally do so in the hollow and broad parts of the body, such as the stomach and chest, where they produce rumbling noises; for when they do not fill the parts so as to be stationary, but have changes of place and movements, there must necessarily be noise and apparent movements from them. But such parts as are fleshy and soft, in these there occur torpor and obstructions, such as happen in apoplexy. But when it (the flatus?) encounters a broad and resisting structure, and rushes against such a part, and this happens when it is by nature not strong so as to be able to withstand it without suffering injury; nor soft and rare, so as to receive or yield to it, but tender, juicy, full of blood, and dense, like the liver, owing to its density and broadness, it resists and does not yield. But flatus, when it obtains admission, increases and becomes stronger, and rushes toward any resisting object; but owing to its tenderness, and the quantity of blood which it (the liver) contains, it cannot be without uneasiness; and for these reasons the most acute and frequent pains occur in the region of it, along with suppurations and chronic tumors (phymata). These symptoms also occur in the site of the diaphragm, but much less frequently; for the diaphragm is a broad, expanded, and resisting substance, of a nervous (tendinous?) and strong nature, and therefore less susceptible of pain; and yet pains and chronic abscesses do occur about it.

23. There are both within and without the body many other kinds of structure, which differ much from one another as to sufferings both in health and disease; such as whether the head be small or large; the neck slender or thick, long or short; the belly long or round; the chest and ribs broad or narrow; and many others besides, all which you ought to be acquainted with, and their differences; so that knowing the causes of each, you may make the more accurate observations.

24. And, as has been formerly stated, one ought to be acquainted with the powers of juices, and what action each of them has upon man, and their alliances towards one another. What I say is this: if a sweet juice change to another kind, not from any admixture, but because it has undergone a mutation within itself; what does it first become?- bitter? salt? austere? or acid? I think acid. And hence, an acid juice is the most improper of all things that can be administered in cases in which a sweet juice is the most proper. Thus, if one should succeed in his investigations of external things, he would be the better able always to select the best; for that is best which is farthest removed from that which is unwholesome.

![]()

Translated by Charles Darwin Adams

1. It appears to me a most excellent thing for the physician to cultivate Prognosis; for by foreseeing and foretelling, in the presence of the sick, the present, the past, and the future, and explaining the omissions which patients have been guilty of, he will be the more readily believed to be acquainted with the circumstances of the sick; so that men will have confidence to intrust themselves to such a physician. And he will manage the cure best who has foreseen what is to happen from the present state of matters. For it is impossible to make all the sick well; this, indeed, would have been better than to be able to foretell what is going to happen; but since men die, some even before calling the physician, from the violence of the disease, and some die immediately after calling him, having lived, perhaps, only one day or a little longer, and before the physician could bring his art to counteract the disease; it therefore becomes necessary to know the nature of such affections, how far they are above the powers of the constitution; and, moreover, if there be anything divine in the diseases, and to learn a foreknowledge of this also. Thus a man will be the more esteemed to be a good physician, for he will be the better able to treat those aright who can be saved, having long anticipated everything; and by seeing and announcing beforehand those who will live and those who will die, he will thus escape censure.

2. He should observe thus in acute diseases: first, the countenance of the patient, if it be like those of persons in health, and more so, if like itself, for this is the best of all; whereas the most opposite to it is the worst, such as the following; a sharp nose, hollow eyes, collapsed temples; the ears cold, contracted, and their lobes turned out: the skin about the forehead being rough, distended, and parched; the color of the whole face being green, black, livid, or lead-colored. If the countenance be such at the commencement of the disease, and if this cannot be accounted for from the other symptoms, inquiry must be made whether the patient has long wanted sleep; whether his bowels have been very loose; and whether he has suffered from want of food; and if any of these causes be confessed to, the danger is to be reckoned so far less; and it becomes obvious, in the course of a day and a night, whether or not the appearance of the countenance proceeded from these causes. But if none of these be said to exist, if the symptoms do not subside in the aforesaid time, it is to be known for certain that death is at hand. And, also, if the disease be in a more advanced stage either on the third or fourth day, and the countenance be such, the same inquiries as formerly directed are to be made, and the other symptoms are to be noted, those in the whole countenance, those on the body, and those in the eyes; for if they shun the light, or weep involuntarily, or squint, or if the one be less than the other, or if the white of them be red, livid, or has black veins in it; if there be a gum upon the eyes, if they are restless, protruding, or are become very hollow; and if the countenance be squalid and dark, or the color of the whole face be changed- all these are to be reckoned bad and fatal symptoms. The physician should also observe the appearance of the eyes from below the eyelids in sleep; for when a portion of the white appears, owing to the eyelids not being closed together, and when this is not connected with diarrhea or purgation from medicine, or when the patient does not sleep thus from habit, it is to be reckoned an unfavorable and very deadly symptom; but if the eyelid be contracted, livid, or pale, or also the lip, or nose, along with some of the other symptoms, one may know for certain that death is close at hand. It is a mortal symptom, also, when the lips are relaxed, pendent, cold, and blanched.

3. It is well when the patient is found by his physician reclining upon either his right or his left side, having his hands, neck, and legs slightly bent, and the whole body lying in a relaxed state, for thus the most of persons in health recline, and these are the best of postures which most resemble those of healthy persons. But to lie upon one’s back, with the hands, neck, and the legs extended, is far less favorable. And if the patient incline forward, and sink down to the foot of the bed, it is a still more dangerous symptom; but if he be found with his feet naked and not sufficiently warm, and the hands, neck, and legs tossed about in a disorderly manner and naked, it is bad, for it indicates aberration of intellect. It is a deadly symptom, also, when the patient sleeps constantly with his mouth open, having his legs strongly bent and plaited together, while he lies upon his back; and to lie upon one’s belly, when not habitual to the patient to sleep thus while in good health, indicates delirium, or pain in the abdominal regions. And for the patient to wish to sit erect at the acme of a disease is a bad symptom in all acute diseases, but particularly so in pneumonia. To grind the teeth in fevers, when such has not been the custom of the patient from childhood, indicates madness and death, both which dangers are to be announced beforehand as likely to happen; and if a person in delirium do this it is a very deadly symptom. And if the patient had an ulcer previously, or if one has occurred in the course of the disease, it is to be observed; for if the man be about to die the sore will become livid and dry, or yellow and dry before death.

4. Respecting the movement of the hands I have these observations to make: When in acute fevers, pneumonia, phrenitis, or headache, the hands are waved before the face, hunting through empty space, as if gathering bits of straw, picking the nap from the coverlet, or tearing chaff from the wall- all such symptoms are bad and deadly.

5. Respiration, when frequent, indicates pain or inflanunation in the parts above the diaphragm: a large respiration performed at a great interval announces delirium; but a cold respiration at nose or mouth is a very fatal symptom. Free respiration is to be looked upon as contributing much to the safety of the patient in all acute diseases, such as fevers, and those complaints which come to a crisis in forty days.

6. Those sweats are the best in all acute diseases which occur on the critical days, and completely carry off the fever. Those are favorable, too, which taking place over the whole body, show that the man is bearing the disease better. But those that do not produce this effect are not beneficial. The worst are cold sweats, confined to the head, face, and neck; these in an acute fever prognosticate death, or in a milder one, a prolongation of the disease; and sweats which occur over the whole body, with the characters of those confined to the neck, are in like manner bad. Sweats attended with a miliary eruption, and taking place about the neck, are bad; sweats in the form of drops and of vapour are good. One ought to know the entire character of sweats, for some are connected with prostration of strength in the body, and some with intensity of the inflammation.

7. That state of the hypochondrium is best when it is free from pain, soft, and of equal size on the right side and the left. But if inflamed, or painful, or distended; or when the right and left sides are of disproportionate sizes;- all these appearances are to be dreaded. And if there be also pulsation in the hypochondrium, it indicates perturbation or delirium; and the physician should examine the eyes of such persons; for if their pupils be in rapid motion, such persons may be expected to go mad. A swelling in the hypochondrium, that is hard and painful, is very bad, provided it occupy the whole hypochondrium; but if it be on either side, it is less dangerous when on the left. Such swellings at the commencement of the disease prognosticate speedy death; but if the fever has passed twenty days, and the swelling has not subsided, it turns to a suppuration. A discharge of blood from the nose occurs to such in the first period, and proves very useful; but inquiry should be made if they have headache or indistinct vision; for if there be such, the disease will be determined thither. The discharge of blood is rather to be expected in those who are younger than thirty-five years. Such swellings as are soft, free from pain, and yield to the finger, occasion more protracted crises, and are less dangerous than the others. But if the fever continue beyond sixty days, without any subsidence of the swelling, it indicates that empyema is about to take place; and a swelling in any other part of the cavity will terminate in like manner. Such, then, as are painful, hard, and large, indicate danger of speedy death; but such as are soft, free of pain, and yield when pressed with the finger, are more chronic than these. Swellings in the belly less frequently form abscesses than those in the hypochondrium; and seldomest of all, those below the navel are converted into suppuration; but you may rather expect a hemorrhage from the upper parts. But the suppuration of all protracted swellings about these parts is to be anticipated. The collections of matter there are to be thus judged of: such as are determined outwards are the best when they are small, when they protrude very much, and swell to a point; such as are large and broad, and which do not swell out to a sharp point, are the worst. Of such as break internally, the best are those which have no external communication, but are covered and indolent; and when the whole place is free from discoloration. That pus is best which is white, homogeneous, smooth, and not at all fetid; the contrary to this is the worst.

8. All dropsies arising from acute diseases are bad; for they do not remove the fever, and are very painful and fatal. The most of them commence from the flanks and loins, but some from the liver; in those which derive their origin from the flanks and loins the feet swell, protracted diarrhoeas supervene, which neither remove the pains in the flanks and loins, nor soften the belly, but in dropsies which are connected with the liver there is a tickling cough, with scarcely any perceptible expectoration, and the feet swell; there are no evacuations from the bowels, unless such as are hard and forced; and there are swellings about the belly, sometimes on the one side and sometimes on the other, and these increase and diminish by turns.

9. It is a bad symptom when the head, hands, and feet are cold, while the belly and sides are hot; but it is a very good symptom when the whole body is equally hot. The patient ought to be able to turn round easily, and to be agile when raised up; but if he appear heavy in the rest of his body as well as in his hands and feet, it is more dangerous; and if, in addition to the weight, his nails and fingers become livid, immediate death may be anticipated; and if the hands and feet be black it is less dangerous than if they be livid, but the other symptoms must be attended, to; for if he appear to bear the illness well, and if certain of the salutary symptoms appear along with these there may be hope that the disease will turn to a deposition, so that the man may recover; but the blackened parts of the body will drop off. When the testicles and members are retracted upwards, they indicate strong pains and danger of death.

10. With regard to sleep- as is usual with us in health, the patient should wake during the day and sleep during the night. If this rule be anywise altered it is so far worse: but there will be little harm provided he sleep in the morning for the third part of the day; such sleep as takes place after this time is more unfavorable; but the worst of all is to get no sleep either night or day; for it follows from this symptom that the insomnolency is connected with sorrow and pains, or that he is about to become delirious.

11. The excrement is best which is soft and consistent, is passed at the hour which was customary to the patient when in health, in quantity proportionate to the ingests; for when the passages are such, the lower belly is in a healthy state. But if the discharges be fluid, it is favorable that they are not accompanied with a noise, nor are frequent, nor in great quantity; for the man being oppressed by frequently getting up, must be deprived of sleep; and if the evacuations be both frequent and large, there is danger of his falling into deliquium animi. But in proportion to the ingesta he should have evacuations twice or thrice in the day, once at night and more copiously in the morning, as is customary with a person in health. The faeces should become thicker when the disease is tending to a crisis; they ought to be yellowish and not very fetid. It is favorable that round worms be passed with the discharges when the disease is tending to a crisis. The belly, too, through the whole disease, should be soft and moderately distended; but excrements that are very watery, or white, or green, or very red, or frothy, are all bad. It is also bad when the discharge is small, and viscid, and white, and greenish, and smooth; but still more deadly appearances are the black, or fatty, or livid, or verdigris-green, or fetid. Such as are of varied characters indicate greater duration of the complaint, but are no less dangerous; such as those which resemble scrapings, those which are bilious, those resembling leeks, and the black; these being sometimes passed together, and sometimes singly. It is best when wind passes without noise, but it is better that flatulence should pass even thus than that it should be retained; and when it does pass thus, it indicates either that the man is in pain or in delirium, unless he gives vent to the wind spontaneously. Pains in the hypochondria, and swellings, if recent, and not accompanied with inflammation, are relieved by borborygmi supervening in the hypochondrium, more especially if it pass off with faeces, urine, and wind; but even although not, it will do good by passing along, and it also does good by descending to the lower part of the belly.

12. The urine is best when the sediment is white, smooth, and consistent during the whole time, until the disease come to a crisis, for it indicates freedom from danger, and an illness of short duration; but if deficient, and if it be sometimes passed clear, and sometimes with a white and smooth sediment, the disease will be more protracted, and not so void of danger. But if the urine be reddish, and the sediment consistent and smooth, the affection, in this case, will be more protracted than the former, but still not fatal. But farinaceous sediments in the urine are bad, and still worse are the leafy; the white and thin are very bad, but the furfuraceous are still worse than these. Clouds carried about in the urine are good when white, but bad if black. When the urine is yellow and thin, it indicates that the disease is unconcocted; and if it (the disease) should be protracted, there maybe danger lest the patient should not hold out until the urine be concocted. But the most deadly of all kinds of urine are the fetid, watery, black, and thick; in adult men and women the black is of all kinds of urine the worst, but in children, the watery. In those who pass thin and crude urine for a length of time, if they have otherwise symptoms of convalescence, an abscess may be expected to form in the parts below the diaphragm. And fatty substances floating on the surface are to be dreaded, for they are indications of melting. And one should consider respecting the kinds of urine, which have clouds, whether they tend upwards or downwards, and upwards or downwards, and the colors which they have and such as fall downwards, with the colors as described, are to be reckoned good and commended; but such as are carried upwards, with the colors as described, are to be held as bad, and are to be distrusted. But you must not allow yourself to be deceived if such urine be passed while the bladder is diseased; for then it is a symptom of the state, not of the general system, but of a particular viscus.

13. That vomiting is of most service which consists of phlegm and bile mixed together, and neither very thick nor in great quantity; but those vomitings which are more unmixed are worse. But if that which is vomited be of the color of leeks or livid, or black, whatever of these colors it be, it is to be reckoned bad; but if the same man vomit all these colors, it is to be reckoned a very fatal symptom. But of all the vomitings, the livid indicates the danger of death, provided it be of a fetid smell. But all the smells which are somewhat putrid and fetid, are bad in all vomitings.

14. The expectoration in all pains about the lungs and sides, should be quickly and easily brought up, and a certain degree of yellowness should appear strongly mixed up with the sputum. But if brought up long after the commencement of the pain, and of a yellow or ruddy color, or if it occasions much cough, or be not strongly mixed, it is worse; for that which is intensely yellow is dangerous, but the white, and viscid, and round, do no good. But that which is very green and frothy is bad; but if so intense as to appear black, it is still more dangerous than these; it is bad, if nothing is expectorated, and the lungs discharge nothing, but are gorged with matters which boil (as it were) in the air-passages. It is bad when coryza and sneezing either precede or follow affections of the lungs, but in all other affections, even the most deadly, sneezing is a salutary symptom. A yellow spittle mixed up with not much blood in cases of pneumonia, is salutary and very beneficial if spit up at the commencement of the disease, but if on the seventh day, or still later, it is less favorable. And all sputa are bad which do not remove the pain. But the worst is the black, as has been described. Of all others the sputa which remove the pain are the best.

15. When the pains in these regions do not cease, either with the discharge of the sputa, nor with alvine evacuations, nor from venesection, purging with medicine, nor a suitable regimen, it is to be held that they will terminate in suppurations. Of empyemata such as are spit up while the sputum is still bilious, are very fatal, whether the bilious portion be expectorated separate, or along with the other; but more especially if the empyema begin to advance after this sputum on the seventh day of the disease. It is to be expected that a person with such an expectoration shall die on the fourteenth day, unless something favorable supervene. The following are favorable symptoms: to support the disease easily, to have free respiration, to be free from pain, to have the sputa readily brought up, the whole body to appear equally warm and soft, to have no thirst, the urine, and faeces, sleep, and sweats to be all favorable, as described before; when all these symptoms concur, the patient certainly will not die; but if some of these be present and some not, he will not survive longer than the fourteenth day. The bad symptoms are the opposite of these, namely, to bear the disease with difficulty, respiration large and dense, the pain not ceasing, the sputum scarcely coughed up, strong thirst, to have the body unequally affected by the febrile heat, the belly and sides intensely hot, the forehead, hands, and feet cold; the urine, and excrements, the sleep, and sweats, all bad, agreeably to the characters described above; if such a combination of symptoms accompany the expectoration, the man will certainly die before the fourteenth day, and either on the ninth or eleventh. Thus then one may conclude regarding this expectoration, that it is very deadly, and that the patient will not survive until the fourteenth day. It is by balancing the concomitant symptoms whether good or bad, that one is to form a prognosis; for thus it will most probably prove to be a true one. Most other suppurations burst, some on the twentieth, some on the thirtieth, some on the fortieth, and some as late as the sixtieth day.

16. One should estimate when the commencement of the suppuration will take place, by calculating from the day on which the patient was first seized with fever, or if he had a rigor, and if he says, that there is a weight in the place where he had pain formerly, for these symptoms occur in the commencement of suppurations. One then may expect the rupture of the abscesses to take place from these times according to the periods formerly stated. But if the empyema be only on either side, one should turn him and inquire if he has pain on the other side; and if the one side be hotter than the other, and when laid upon the sound side, one should inquire if he has the feeling of a weight hanging from above, for if so, the empyema will be upon the opposite side to that on which the weight was felt.

17. Empyema may be recognized in all cases by the following symptoms: In the first place, the fever does not go off, but is slight during the day, and increases at night, and copious sweats supervene, there is a desire to cough, and the patients expectorate nothing worth mentioning, the eyes become hollow, the cheeks have red spots on them, the nails of the hands are bent, the fingers are hot especially their extremities, there are swellings in the feet, they have no desire of food, and small blisters (phlyctaenae) occur over the body. These symptoms attend chronic empyemata, and may be much trusted to; and such as are of short standing are indicated by the same, provided they be accompanied by those signs which occur at the commencement, and if at the same time the patient has some difficulty of breathing. Whether they will break earlier or later may be determined by these symptoms; if there be pain at the commencement, and if the dyspnoea, cough, and ptyalism be severe, the rupture may be expected in the course of twenty days or still earlier; but if the pain be more mild, and all the other symptoms in proportion, you may expect from these the rupture to be later; but pain, dyspnoea, and ptyalism, must take place before the rupture of the abscess. Those patients recover most readily whom the fever leaves the same day that the abscess bursts,- when they recover their appetite speedily, and are freed from the thirst,- when the alvine discharges are small and consistent, the matter white, smooth, uniform in color, and free of phlegm, and if brought up without pain or strong coughing. Those die whom the fever does not leave, or when appearing to leave them it returns with an exacerbation; when they have thirst, but no desire of food, and there are watery discharges from the bowels; when the expectoration is green or livid, or pituitous and frothy; if all these occur they die, but if certain of these symptoms supervene, and others not, some patients die and some recover, after a long interval. But from all the symptoms taken together one should form a judgment, and so in all other cases.

18. When abscesses form about the ears, after peripneumonic affections, or depositions of matter take place in the inferior extremities and end in fistula, such persons recover. The following observations are to be made upon them: if the fever persist, and the pain do not cease, if the expectoration be not normal, and if the alvine discharges be neither bilious, nor free and unmixed; and if the urine be neither copious nor have its proper sediment, but if, on the other hand, all the other salutary symptoms be present, in such cases abscesses may be expected to take place. They form in the inferior parts when there is a collection of phlegm about the hypochondria; and in the upper when the hypochondria continue soft and free of pain, and when dyspnoea having been present for a certain time, ceases without any obvious cause. All deposits which take place in the legs after severe and dangerous attacks of pneumonia, are salutary, but the best are those which occur at the time when the sputa undergo a change; for if the swelling and pain take place while the sputa are changing from yellow and becoming of a purulent character, and are expectorated freely, under these circumstances the man will recover most favorably and the abscess becoming free of pain, will soon cease; but if the expectoration is not free, and the urine does not appear to have the proper sediment, there is danger lest the limb should be maimed, or that the case otherwise should give trouble. But if the abscesses disappear and go back, while expectoration does not take place, and fever prevails, it is a bad symptom; for there is danger that the man may get into a state of delirium and die. Of persons having empyema after peripneumonic affections, those that are advanced in life run the greatest risk of dying; but in the other kinds of empyema younger persons rather die. In cases of empyema treated by the cautery or incision, when the matter is pure, white, and not fetid, the patient recovers; but if of a bloody and dirty character, he dies.

19. Pains accompanied with fever which occur about the loins and lower parts, if they attack the diaphragm, and leave the parts below, are very fatal. Wherefore one ought to pay attention to the other symptoms, since if any unfavorable one supervene, the case is hopeless; but if while the disease is determined to the diaphragm, the other symptoms are not bad, there is great reason to expect that it will end in empyema. When the bladder is hard and painful, it is an extremely bad and mortal symptom, more especially in cases attended with continued fever; for the pains proceeding from the bladder alone are to kill the patient; and at such a time the bowels are not moved, or the discharges are hard and forced. But urine of a purulent character, and having a white and smooth sediment, relieves the patient. But if no amendment takes place in the characters of the urine, nor the bladder become soft, and the fever is of the continual type, it may be expected that the patient will die in the first stages of the complaint. This form attacks children more especially, from their seventh to their fifteenth year.

20. Fevers come to a crisis on the same days as to number on which men recover and die. For the mildest class of fevers, and those originating with the most favorable symptoms, cease on the fourth day or earlier; and the most malignant, and those setting in with the most dangerous symptoms, prove fatal on the fourth day or earlier. The first class of them as to violence ends thus: the second is protracted to the seventh day, the third to the eleventh, the fourth to the fourteenth, the fifth to the seventeenth, and the sixth to the twentieth. Thus these periods from the most acute disease ascend by fours up to twenty. But none of these can be truly calculated by whole days, for neither the year nor the months can be numbered by entire days. After these in the same manner, according to the same progression, the first period is of thirty-four days, the second of forty days, and the third of sixty days. In the commencement of these it is very difficult to determine those which will come to a crisis after a long interval; for these beginnings are very similar, but one should pay attention from the first day, and observe further at every additional tetrad, and then one cannot miss seeing how the disease will terminate. The constitution of quartans is agreeable to the same order. Those which will come to a crisis in the shortest space of time, are the easiest to be judged of; for the differences of them are greatest from the commencement, thus those who are going to recover breathe freely, and do not suffer pain, they sleep during the night, and have the other salutary symptoms, whereas those that are to die have difficult respiration, are delirious, troubled with insomnolency, and have other bad symptoms. Matters being thus, one may conjecture, according to the time, and each additional period of the diseases, as they proceed to a crisis. And in women, after parturition, the crises proceed agreeably to the same ratio.

21. Strong and continued headaches with fever, if any of the deadly symptoms be joined to them, are very fatal. But if without such symptoms the pain be prolonged beyond twenty days, a discharge of blood from the nose or some abscess in the inferior parts may be anticipated; but while the pain is recent, we may expect in like manner a discharge of blood from the nose, or a suppuration, especially if the pain be seated above the temples and forehead; but the hemorrhage is rather to be looked for in persons younger than thirty years, and the suppuration in more elderly persons.

22. Acute pain of the ear, with continual and strong fever, is to be dreaded; for there is danger that the man may become delirious and die. Since, then, this is a hazardous spot, one ought to pay particular attention to all these symptoms from the commencement. Younger persons die of this disease on the seventh day, or still earlier, but old persons much later; for the fevers and delirium less frequently supervene upon them, and on that account the ears previously come to a suppuration, but at these periods of life, relapses of the disease coming on generally prove fatal. Younger persons die before the ear suppurates; only if white matter run from the ear, there may be hope that a younger person will recover, provided any other favorable symptom be combined.

23. Ulceration of the throat with fever, is a serious affection, and if any other of the symptoms formerly described as being bad, be present, the physician ought to announce that his patient is in danger. Those quinsies are most dangerous, and most quickly prove fatal, which make no appearance in the fauces, nor in the neck, but occasion very great pain and difficulty of breathing; these induce suffocation on the first day, or on the second, the third, or the fourth. Such as, in like manner, are attended with pain, are swelled up, and have redness (erythema) in the throat, are indeed very fatal, but more protracted than the former, provided the redness be great. Those cases in which both the throat and the neck are red, are more protracted, and certain persons recover from them, especially if the neck and breast be affected with erythema, and the erysipelas be not determined inwardly. If neither the erysipelas disappear on the critical day, nor any abscess form outwardly, nor any pus be spit up, and if the patient fancy himself well, and be free from pain, death, or a relapse of the erythema is to be apprehended. It is much less hazardous when the swelling and redness are determined outwardly; but if determined to the lungs, they superinduce delirium, and frequently some of these cases terminate in empyema. It is very dangerous to cut off or scarify enlarged uvulae while they and red and large, for inflammations and hemorrhages supervene; but one should try to reduce such swellings by some other means at this season. When the whole of it is converted into an abscess, which is called Uva, or when the extremity of the variety called Columella is larger and round, but the upper part thinner, at this time it will be safe to operate. But it will be better to open the bowels gently before proceeding to the operation, if time will permit, and the patient be not in danger of being suffocated.