8

The New Cardinal

IPPOLITO ARRIVED AT the Porta del Popolo on Sunday, 26 October, and, as was the custom, spent that night in a palace outside the gate before making his official entry into Rome the following morning. Somewhat to his surprise, a papal messenger was waiting at the palace with orders to escort him to the Vatican that evening for a private audience with Paul III. Ippolito rode unnoticed through the city streets and spent four hours with the Pope discussing the political situation in France, before returning to his lodgings outside the gate for the night. The next day he made his entry, this time formally escorted by all the cardinals resident in Rome. Ippolito was dressed in his new red cape, made for the occasion by Antoine the tailor, but he was symbolically hatless, in contrast to the other cardinals, who were in full regalia.

Rome in 1539 had a population of around 40,000, much the same size as Ferrara. Considering its importance, the city was small – Paris had a population of 200,000 – and it occupied only a third of the land enclosed by the ancient imperial walls, which had been built to protect a capital that had once boasted nearly a million inhabitants. Renaissance Rome was clustered along the banks of the Tiber, a maze of narrow streets linking the commercial heart of the city by the Capitol to the focus of papal power across the river at the basilica of St Peter’s. Ippolito’s cavalcade made its way through the busy streets, past shops and warehouses built on the ruins of ancient temples, churches that dated back to the early centuries of Christian faith, and contemporary palaces whose façades were decorated with the myths and history of antiquity. Rome’s past was rich and unique, and, despite its scruffy appearance, the city had an air of grandeur that set it apart from other European centres. Ippolito jostled his way through the crowds of people on the bridge over the Tiber, past the imposing papal fortress of Castel Sant’Angelo, and into the Via Alessandrina, the street built by his grandfather Pope Alexander VI to provide a grand approach to St Peter’s and the Vatican palace, the heart of the Christian world. Here, in a fitting climax to a majestic papal ceremony, Paul III formally placed a cardinal’s hat on Ippolito’s head.

St Peter’s and the Vatican palace

Late in the afternoon Ippolito rode back across the city, still with his escort of cardinals and now proudly wearing his hat in public for the first time. The cardinals accompanied him to his new home, the palace he had rented from his cousin Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga. This was a grand residence in a prestigious location and entirely appropriate to Ippolito’s perception of his new status. It was situated on the Via del Corso, the street that linked the Porta del Popolo with the Capitol, once the religious centre of the ancient Roman empire where the great Temple of Jupiter had looked out across the Roman Forum. The temple had long since disappeared, but the site was now embellished with some of the most famous bronze statues of antiquity – the Wolf suckling the twins Romulus and Remus, the Spinario or Thorn-Picker, and the equestrian monument to Marcus Aurelius, which Paul III had moved to the hill the year before. A tax, which had been raised from the owners of all the palaces in the neighbourhood in 1538 to finance street repairs, had assessed Gonzaga’s palace as second only to the Palazzo Venezia, Paul III’s summer residence nearby. Ippolito and his escort of cardinals arrived that evening to find its main entrance decked with huge festoons of ivy and myrtle that sparkled with gold sequins. The arrangement had cost 5 scudi, enough to buy ten pheasants or sixty-six chickens.

The palace was certainly grander than the Palazzo San Francesco, but inside much was familiar. Ippolito’s own carved wooden chests and other pieces of furniture from Ferrara were now installed in the grand reception rooms and his private apartments. The walls were decorated with his tapestries and his expensive set of Spanish leather hangings (these were so heavy that they had needed five mules to transport them to Rome). The furnishing of the palace had been supervised by Alessandro Zerbinato, the major-domo, who had arrived in Rome a few days earlier. It had been a tiresome business – the tapestries did not fit properly, and a tailor had to be hired to shorten several of the pieces. The whole building was clean and welcoming, thanks to a lot of hard work on the part of Apollonio Minotto, who had spent the past two months in Rome transforming the empty and somewhat dilapidated palace into a setting that would befit Ippolito’s new status.

Ippolito’s own apartments were particularly splendid. In addition to the chests and hangings from Ferrara, Minotto had bought several more pieces of furniture for these rooms. He commissioned two cabinet-makers in Rome to make eight chairs – four decorated with bone inlay, four with intarsia – and a local upholsterer had covered them in gold brocade and red kermes velvet, with red and gold fringes. These materials came from Minotto’s stores and had been sent down to Rome by Ippolito’s agent in Florence. Their price was not entered in Minotto’s ledger, but they must have been expensive. The colour theme of red and gold was carried through in other decorative details. The door hangings were made of red velvet, bordered with gold brocade and embroidered in gold thread with Ippolito’s coat-of-arms. In his bedroom was a small table made by a carpenter in the Via de’ Banchi, its modest price of just over 1 scudo carefully disguised by an expensive red velvet cover. Most of the textiles – 70 metres of the gold brocade and 74 metres of the red velvet – had been used to make a magnificent set of hangings for Ippolito’s bed. Minotto had spent over 4 scudi on the bed itself, which he bought from another carpenter in the Via de’ Banchi. It was constructed of walnut with metal fittings but was evidently not very well made – one of the iron pieces came loose a month later and the carpenter had to be summoned to resolder it.

![]()

Receiving his hat from Paul III was only the first of a series of arcane ceremonies that Ippolito had to undergo to mark this ancient rite of passage. Two days later, on Wednesday, 29 October, he attended his first private Consistory, the regular sessions of the College of Cardinals chaired by the Pope. At this first session, Paul III ceremoniously ‘closed his mouth’ (os claudit), forbidding him to speak in Consistory. Ippolito, used to the secular excitements of the French court, was less than impressed with the stultifying ritual of the papal court and he complained to Ercole that the services were ‘tedious and long’. His mouth was finally ‘opened’ on 10 November when, in the last of the ceremonies, Paul III gave him his ring of office and assigned him a titular church. Ippolito was now the Cardinal of Santa Maria in Aquiro, a small church behind the Pantheon, which dated back to the eighth century and had originally been attached to a hospital for pilgrims. It was not a very prestigious title, as he informed his brother, but ‘nothing better was vacant’, though he took comfort from the fact that ‘they say it is one of the oldest’. Intriguingly, his companion at this ceremony was another new cardinal, the poet Pietro Bembo. Bembo was now 69 years old, but he had once been the lover of Lucretia Borgia, Ippolito’s mother. Paul III, who had a mischievous sense of humour and certainly knew of the liaison between Lucretia and Bembo, clearly found the combination irresistible.

The impact of Ippolito’s new status was soon apparent. Suddenly, after years of opposition to the establishment of his rights to his benefices, the difficulties evaporated. Charles V lifted the sequestration order on the archbishopric of Milan and Paul III gave his official approval to the sees and abbeys that Ippolito had received from Francis I. Ippolito now had an impressive list of titles – Cardinal of Ferrara, Archbishop of Milan and Lyon, two of Europe’s most important sees, and Abbot of the lucrative abbeys of Jumièges in Normandy and St-Médard at Soissons. It is a sign of the secular nature of the Church before the Counter-Reformation that Ippolito was not ordained as a priest until 1564.

The formal confirmation of his benefices at last allowed Ippolito to advance the Church careers of some of his courtiers. Tomaso Mosto now acquired a vicariate in the diocese of Milan and a parish in Lyon, while Tomaso del Vecchio also received a vicariate in Milan and a canonicate at Lyon. ‘And so, slowly, I am getting there,’ Ippolito wrote to his brother, though he still had to wait for the Curia to disgorge all the paperwork before he could obtain any financial benefit.

Marcobruno dalle Anguille, Ippolito’s lawyer, came down from Ferrara in November to oversee this lengthy process and submitted an itemized bill of 90 scudi which listed over fifty different payments – effectively bribes – made to various officials in the labyrinthine bureaucracy of the Curia. The notoriously corrupt papal administration was staffed by men who had bought their posts and whose income depended on charges that were levied at every conceivable stage of the process. Each benefice required a cedula consistoriale, an official form issued in Consistory to confirm papal agreement to the appointment, in order to start the process of issuing the bull, or papal edict. Each bull had to be written out formally. The cost of writing the bulls for Lyon and St-Médard at Soissons came to 10½ scudi, considerably more than mere payment for a scribe’s work. The bulls then had to be registered in the Datary. There were five separate charges for this – the formal request to the Datary for registration, the registration itself, an official examination of the registration, the lead seal needed to fasten the registered bull and, finally, the specially made box in which it was kept. The bulls then all had to be formally settled, a process which required more lead seals, and the titles registered by the notary of the Apostolic Chamber. In the case of the French benefices, copies of the bulls also had to be made by an official dealing with French affairs, and then sent to France.

Meanwhile, Ippolito’s household began to familiarize themselves with the chaotic and sprawling city. There seem to have been 100 men in the palace – Minotto had commissioned that number of mattresses and pillows – as well as the stable boys who slept in the stables. Around sixty of these men belonged to the household proper, while the rest were servants of the grander members of staff. Their life in Rome is particularly well-documented in two surviving ledgers. One of these is the wardrobe account book, kept by Tomaso Mosto’s assistant, Giovanbattista Orabon, in his neat but rather ornate handwriting. The ledger was valuable – its 200 pages were secured with five red clasps, and Orabon ordered a wooden chest with locks from a carpenter to keep it safe. The account book is a mine of information. Mosto was not only head of Ippolito’s wardrobe but also his treasurer, and the book covers far more than just the cost of Ippolito’s clothes. Orabon listed Ippolito’s income over the first seven pages and then detailed all the sums handed out by Mosto to members of the household to settle Ippolito’s bills. For the first time we have precise information regarding Ippolito’s expenditure outside Ferrara – the cost of travel, the presents and tips he gave, the alms handed out by Ippolito d’Argenta the footman, the supplies bought by Assassino and Zudio for the Chamber, the materials, sewing thread and buttons bought by Antoine the tailor, the advances that Mosto gave every two or three days to Francesco Salineo to cover the expenses of the stables and to Ludovico Morello, the purveyor, and even the cost of delousing the heads of the pages and the boy sopranos. The other ledger to survive belonged to Morello. It provides a fascinating insight into his daily routine, shopping for the food needed by the cooks and credenzieri for each day’s meals and for more general household supplies.

As the household was settled in Rome for the foreseeable future, Zerbinato drew up contracts with various tradesmen for regular supplies of meat, poultry, fish, groceries, candles and firewood. They all charged pro rata for their goods, except for the greengrocer, who had a shop in the small square in front of the Pantheon and sent salads and vegetables at a set rate of 10 scudi a month. Zerbinato settled their accounts each month with funds he withdrew directly from Mosto. Morello bought everything else, including all the additional meat, fish and groceries not supplied on contract that were needed for entertaining. Most days he spent about 2 or 3 scudi on food, though his expenditure rose to 10 or 12 scudi on the days when Ippolito had guests – he seems to have given his dinner parties regularly on Wednesdays. It is clear from Morello’s ledger that, although the basic diet of the household was much the same as it had been in France, there were significant local and seasonal variations. The fruit he bought included apples, pears, lemons and oranges, but there were also more exotic fruits and vegetables that would have been unavailable in Lyon during the winter, such as fresh grapes, pomegranates, fennel and cardoons. Other novelties included a lot of pasta, mainly lasagna and vermicelli, as well as local cheeses, which Morello just described as Roman, and southern Italian wines from Ischia, Naples, Salerno and the Alban hills outside Rome.

The butcher supplied veal, beef, goat and mutton, while the poulterer delivered capons, hens, chickens, geese and ducks. Morello regularly bought items such as sausages, which he found in a shop near the greengrocer at the Pantheon, sweetbreads, giblets, calves’ feet to make jelly and sheeps’ heads for the dogs. Above all, this was the season for game, and Ippolito feasted on wild boar, hare, pheasant, duck, partridge, plovers, thrushes and other small birds. At nearly 1 scudo each, pheasants were an expensive luxury – Morello could buy seventy thrushes for the same amount.

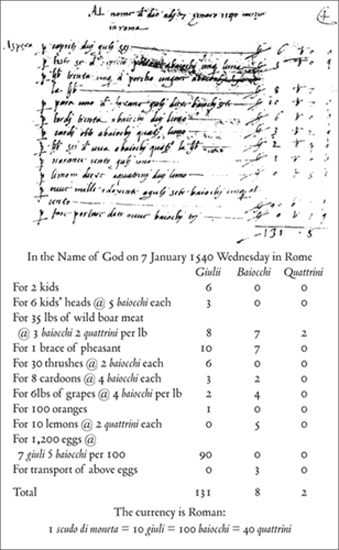

A page from Ludovico Morello’s ledger outlining his expenditure on 7 January 1540

On Fridays the household ate fish, either freshwater varieties or seafish from the Mediterranean, both of which were supplied by the fishmonger. Morello also bought fish, occasionally eels but mostly large quantities of clams, mussels, cockles and other shellfish, as well as salted anchovies and tuna. Another of his tasks was to take the kitchen knives to be sharpened every fortnight or so, and he bought miscellaneous supplies for the household, including brooms, toothpicks, kitchen equipment (the French pastry cook’s palette knife needed a new handle), and plates for the staff dining-rooms, which seem to have been replaced every month.

Living in Rome must have been a challenge, not only for the Frenchmen in the household who had to use another language, but also for those seasoned travellers from Ferrara. The men had to pay regular visits to the Roman customs house down by the Tiber where a tax was charged on everything entering the city. The officials also demanded payment for opening the crates – the goods sent from Ferrara by Fiorini, the bales of materials from Florence and the barrels of wine from Ischia. The men also had to learn a completely different set of weights, measures and currency. The local Roman currency was decimal and its principal coin, the scudo di moneta, was divided into giulii and baiocchi – 1 scudo di moneta was worth 10 giulii or 100 baiocchi. Morello kept his accounts in the local scudi di moneta, but Orabon preferred to keep his in gold scudi, which were, confusingly, worth 105 baiocchi each. Strangers in a strange city, they lacked the influence that had come from being attached either to a royal or a ducal court. They clearly preferred familiar accents in this cosmopolitan city, and several shopkeepers mentioned in the ledgers came from Ferrara or France. Mosto bought Ippolito’s boots and shoes from a cobbler called Alessandro da Ferrara and his breeches and hose from a French hosier, Gian le Mer. Others, including the haberdasher where Antoine the tailor bought most of his supplies, came from northern Italy.

Antoine was especially busy sewing new clothes for Ippolito, whose dress in Rome was markedly more clerical than it had been in France. Although Ippolito continued to wear secular clothes for social events, he needed a cardinal’s wardrobe for official occasions, in particular for attendance at the Vatican. There were no doublets or saglii in this uniform – cardinals did not show off their figures in tight-fitting clothes but wore long shapeless tunics, cloaks and capes. Above all, their outer wear was bright red, the colour being a badge of their office. Antoine made Ippolito a red consistorial cloak (capa consistoriale), its hood lined with red taffetta, and several short ecclesiastical capes – one in red wool, another in red satin and a third in red damask, for which Antoine charged nearly ½ scudo just for covering the matching buttons. He also made Ippolito a heavy riding-coat to wear whenever he rode across Rome to the Vatican. Mosto bought three new red caps of red cloth from a hatter for Ippolito to wear under his mitre when he attended papal mass – the same hatter also made Ippolito a rather less ecclesiastical confection of black velvet and peacock feathers. The cardinal’s hat which Ippolito had received from Paul III was kept in a wooden hat box that Mosto bought from a scabbard-maker in Rome – it was appropriately covered in red leather at a cost of 1½ scudi.

Ippolito’s household continued to grow. He took on several new pages from prominent Roman families and increased the number of his valets from four to six. One of the new valets was Pompilio Caracciolo, a member of the Neapolitan aristocracy, who had joined the household as a page several years before. The other was a Roman, Julio Bochabella (his surname translates as Goodmouth), who was taken on specifically to look after Ippolito’s gloves. A Flemish flautist joined the household too (in addition to a golden hello of 5 scudi, Ippolito provided him with smart new clothes, including a black taffeta doublet made by Antoine the tailor, and several pairs of leather shoes).

For the first time Ippolito now added a female member of staff. Agnese da Viterbo was employed full-time to wash his clothes – the rest of the household’s washing was sent out to laundries. She received a monthly salary worth 29 scudi a year, slightly less than the squires but without the advantage of bed and board (she was also paid extra for sewing and repairing Ippolito’s clothes).

Like all grand households in Rome, Ippolito employed a water-carrier. The ancient aqueducts had been comprehensively destroyed when the city was sacked in 1527, and most of the water used in the city now had to be carted daily from the Tiber. The water must have been clean because Paul III insisted on taking bottles of it with him whenever he travelled.

The most surprising new face at the palace that autumn was the goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, whom Ippolito had last seen in Lyon in 1537 when he handed over an advance for a commission of a silver jug and basin. Cellini had spent the past year imprisoned in the dungeons of Castel Sant’Angelo on a charge of stealing papal jewels worth 80,000 scudi, which had been entrusted to him by Clement VII during the Sack of Rome. According to Cellini’s autobiography, it was Ippolito himself who managed to obtain his release from the castle one night while he was having dinner with Paul III. Cellini’s vivid, and possibly scurrilous, account of the evening describes the Pope indulging in his weekly bout of drinking to excess and, in answer to Ippolito’s request for Cellini’s release, drunkenly roaring at his guest to take the prisoner home, at once. Whatever the truth of the story, Cellini was released on 24 November, and it was probably a condition of his release that he should move into Ippolito’s palace. He first appears in the ledgers in January 1540 when Mosto bought him a large wooden table, a supply of charcoal and a small goldsmith’s furnace to set up the workshop where he was to make the still-unfinished jug and basin, which Ippolito wanted to give to Francis I. Cellini was not, strictly speaking, part of Ippolito’s household – he received no wages, though he did live free of charge in the palace and ate in the staff dining-room. However, he managed to persuade Ippolito to provide money for wages for his two assistants. They were not salaried employees but were paid out of the sundries account, earning a total of 7 scudi a month, a handsome retainer, though a lot less than Ippolito paid either his tailor or his musicians.

![]()

It must have taken Ippolito some time to get used to life at the papal court and to a routine that involved far more official duties than he had had in France. His letters home to Ercole refer to endless visits to the Vatican – for religious services, Consistory meetings two or three times a week and lunches with the Pope and his pious ecclesiastical advisers. Cardinals were paid for their attendance in the Consistory, though not very much – Orabon recorded 70 scudi forwarded to Ippolito from the papal banker for his remuneration for the five months he spent in Rome. He was also expected to join his colleagues when they rode to the Porta del Popolo to give a formal welcome to important visitors arriving in Rome. One of his fellow cardinals described him as ‘very reserved’ – he almost certainly had little to contribute to discussions of the finer details of papal policy – but also ‘very sincere and very lazy’.

On his visits to the Vatican Ippolito would have seen the new St Peter’s in the process of construction, and the interior of the palace undergoing a major refurbishment: the money Ercole II had paid to settle his dispute with the Pope, and to acquire Ippolito’s hat, was being used to magnificent effect. In the Sistine Chapel Michelangelo was half way through painting his Last Judgement. This huge fresco above the altar had been started in 1537 and was finally unveiled in October 1541. Paul III was also converting the apartments nearby into a splendid suite of rooms, which included the Sala Regia, a hall for the reception of kings and princes, and building a grandiose staircase to provide access to these rooms from the piazza in front of St Peter’s. Ippolito made no mention of the projects in his letters to Ercole, nor did he comment on the Borgia apartments, which he almost certainly also saw. These rooms had been decorated by Pope Alexander VI in the 1490s and contained a portrait of Ippolito’s grandfather proudly viewing Christ’s Resurrection – one wonders whether Ippolito noticed the ceiling, which was decorated with images that traced the descent of the Borgias from the ancient Egyptian deities, Isis and Osiris.

Ippolito’s letters to his brother contained regular news from France, some received through personal letters from Francis I, but most of it gleaned from the French ambassadors in Rome. Francis I had been seriously ill during the autumn, but it is not clear what was wrong with him. ‘The King’, Ippolito wrote, ‘has been very ill with a catarrh which descended to his testicles and gave him much pain but thank God it has broken, the catarrh has come out and he is a lot better.’ There was also much discussion of Francis I’s invitation to Charles V to spend Christmas and New Year in France. Most of the news, however, was second-hand. Life in Rome was far less exciting than it had been in France. High politics and low gossip were replaced by more mundane local issues and, above all, by the exchange of political favours. Ippolito had moved several notches up the ladder of political patronage, and Ercole II began to exploit the advantages of having a brother who was a cardinal, expecting him to use his influence with Paul III on yet another problem that had arisen between Rome and Ferrara – the ownership of some salt-pans on the Adriatic coast. Many of Ippolito’s letters deal with his meetings with Paul III to discuss this issue, though it remained largely unresolved.

Ippolito was also expected to help members of the papal court whose clients wanted posts in the ducal administration in Ferrara. Cardinal Guido Ascanio Sforza, another of Paul III’s grandsons, wanted the post of governor of Reggio for the brother of his major-domo, while the Venetian ambassador sought a position for a friend of his in Ercole II’s army. Cardinal Alessandro Farnese asked Ippolito to write to Ercole for help in asserting his authority in one of his benefices in the diocese of Reggio where squatters had moved in, sold off much of the produce, pocketed the money and refused to allow Farnese’s procurator to take possession. Ippolito’s chief musician, Francesco dalla Viola, asked him to intervene with the Duke on behalf of his brother. The brother, who was one of Ercole’s musicians, was in prison on a charge of murdering the wife of a colleague after he had caught her in the act of adultery. Ippolito asked Ercole to release Francesco’s brother – ‘I know little about the crime though I know it is of some importance’ – and pleaded with him to consider ‘the brotherly bonds between us, and I ask you not out of justice but out of pity for the feelings of the brothers’.

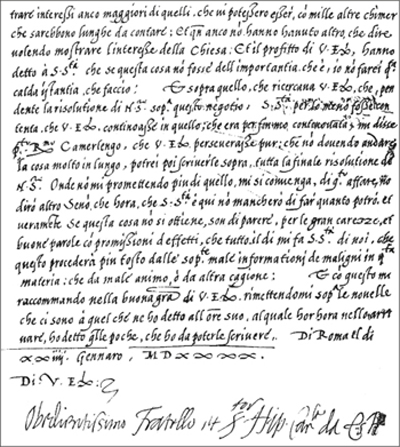

Part of a long leter, mostly dealing with the negotiations Ippolito was conducting on his brother’s behalf regarding the Duke’s ownership of some salt pans on the Adriatic coast, written in a particuarly elegant Italian script

There were problems that required Ippolito’s attention in Rome too. His chaplain, Giovanjacomo Magnanino, had started legal action on Ippolito’s behalf against a certain Captain Domeneghino without his master’s knowledge. ‘I am furious’, Ippolito wrote, ‘and wanted to sack him immediately, but I have decided to keep him on because the process is not far advanced and can be stopped, and also because it is better to keep him in my household, so I have ticked him off, telling him that if he wants to keep my favour he must not only promise never to anything like this again but must also revoke and rescind everything that he has done. He has promised to do so, and it will be a lesson to him, and to my household.’

![]()

Despite his duties, Ippolito still managed to enjoy himself. His affable nature and his love of gossip seem to have made him popular in Rome. There may have been no tennis but there was plenty of gambling and hunting, and also women. Ippolito began a mild flirtation with the Princess of Salerno, the wife of Ferrante Sanseverino, a distant cousin of Charles V. She sent him a present of some wine and fruit – we do not know exactly why – and Ippolito responded with a lavish gift of black velvet, worth about 24 scudi. The imbalance of this gesture suggests he was expecting something in return. There were also several old companions in Rome – his younger brother Francesco came up from Naples for Christmas, and Ridolfo Campeggio arrived in early December from Bologna. Ippolito’s social circle was wide and included not only the Farnese family, members of the Roman nobility and the French envoys in Rome, but also, now that peace had been established between Francis I and Charles V, many Spaniards. He lost 13 scudi gambling one afternoon with the Spanish ambassador. He was made godfather to the daughter of Girolamo Orsini, a commander in the papal army, and gave her a valuable diamond ring as a christening present – Orsini sent Ippolito a basket of salad a few days later, by way of saying thank you. He also made the acquaintance of Margaret of Austria, Charles V’s 17-year-old illegitimate daughter. After her first husband, Alessandro de Medici, had been murdered, she was forced to marry the 13-year-old Ottavio Farnese, younger brother of Cardinal Alessandro. The union was proving far from satisfactory and there was much speculation in Rome as to why it remained unconsummated (Margaret finally gave birth to twins, named Carlo and Alessandro, after their imperial and papal grandfathers, in 1545).

Ippolito’s dogs finally arrived from France in early December, complete with new dog-chains ordered by Fiorini in Ferrara, in time for them to accompany him hunting with Margaret of Austria. The outing was not a great success. ‘I have never seen worse hunting,’ Ippolito wrote scornfully to Ercole, ‘the whole day passed without us seeing anything, which did not please me, though it was a lovely day and it was good to have some exercise’. Life in Rome must have been sedentary by French standards – as a cardinal Ippolito had to ride a mule in the city – but there was always gossip to keep him entertained. Ippolito spent most of that day talking to Pier Luigi Farnese, Paul III’s son and Margaret of Austria’s father-in-law, discussing which men might be made cardinals by the Pope at Christmas. Pier Luigi was remarkably candid, and the list he gave Ippolito turned out to be extremely accurate. The names included Ippolito’s cousin, Enrique Borgia, and Ippolito passed the information on to his brother in a letter that evening. He must have been relieved that it was no longer his own candidacy that hung in the balance.

The celebrations for Christmas and New Year in Rome were splendid and, apart from the obligatory religious services, predominantly secular, with masked balls and magnificent banquets hosted by the Pope, though no jousting. Neverthless Ippolito’s enjoyment of them must have been somewhat diminished by the knowledge that he was missing royal parties and entertainments in France. Charles V had arrived at Bayonne on 27 November, where he was met by the Dauphin and the Duke of Orléans – Francis I was still convalescent – and the two princes escorted the Emperor to Loches, where he met the King. The court then proceeded through Blois, Amboise and Orléans to Paris, where the two old rivals entered the city amid much pomp on 1 January, and finally to St-Quentin, where they parted, with affection, on 24 January. Ippolito sent several presents to France, including a suit of jousting armour for the Dauphin and eight peregrine falcons for Francis I, a gift which cost him not only the price of the birds themselves (70 scudi), but also the expense of sending them to France with a falconer (25 scudi). He must have envied Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who had been sent by his grandfather, Paul III, as papal legate for this historic meeting (the Cardinal stayed three days as Ippolito’s guest in the archiepiscopal palace in Lyon, and wrote to thank him for his hospitality).

By all accounts Ippolito got on well with the Farnese. Pier Luigi gave him a horse and Paul III, in a marked sign of papal favour, offered to install Ippolito as Archpresbyter of St Peter’s, a sinecure that had once been held by Ippolito’s eponymous uncle. Ippolito celebrated New Year at the Vatican and gave tips of 1 scudo each to the footmen, sommeliers and credenzieri of various members of the Farnese family who were present, among them the Pope, Pier Luigi, Ottavio and Margaret of Austria. He also tipped the soldiers of the papal guard at Castel Sant’Angelo, while Cagneto, one of Paul III’s buffoons, received 5 scudi, and the son of another buffoon, Rosso, who had amused Ippolito so much in Nice in June 1538, was given a velvet outfit made by Antoine the tailor that cost 14 scudi. The boy must have been small – Antoine usually used 3 metres of material for one of Ippolito’s doublets, but this outfit only took 1¾ metres. It consisted of a turquoise velvet hat and doublet, turquoise hose and matching breeches made of taffeta threaded with velvet of the same colour and lined in contrasting dark red cloth.

The revelries continued throughout January, finishing only with the end of Carnival and the onset of Lent – Shrove Tuesday fell on 11 February in 1540. Paul III invited Ippolito on several hunting expeditions in the marshes and woods near Civitavecchia. Mosto’s ledger recorded a tip to two poor men who found some deer he had killed, which suggests that the Pope’s hunts were considerably more successful than the outing with Margaret of Austria. On 7 January, a Wednesday, Ippolito hosted a dinner party for Don Luis d’Avila, Charles V’s envoy in Rome. Morello spent 13 scudi on food and the menu included wild boar, a brace of pheasant, thirty thrushes and 100 oranges (see p. 236). He also recorded the delivery of twenty barrels of wine that day. The guests were entertained by music from Ippolito’s singers, and one of the pages danced to the accompaniment of two instrumentalists hired for the occasion. There was also a theatrical entertainment one evening in early February when a company of actors staged a comedy at the palace of Cardinal Niccolò Gaddi, a Florentine and a friend of Luigi Alamanni, Ippolito’s new secretary. Gaddi may have been the host, but it was Ippolito who financed the performance, giving 75 scudi to the actors for the construction and decoration of their stage.

The Carnival celebrations culminated with a spectacular parade of floats, in which the Roman elite – cardinals, barons and bankers – competed for magnificence. Ippolito, needless to say, commissioned his own elaborate float. The project, which cost 46 scudi, was organized by Ippolito’s musician, Francesco della Viola, with the assistance of Cellini. They converted a cart to look like a ship at sea, using real sails rented from a sail-maker’s shop down by the Tiber. The cart was covered with old sheets from the wardrobe that had been painted to resemble the ship’s hull, while the ‘deck’ was adorned with festoons of greenery. It was manned by a crew of singing children who, sensibly, were tied to the structure with bands of cloth to stop them falling off, and given apples as a treat. The bill for the project, detailed precisely by Orabon in the sundries account, lists nails, planks of wood, rope, material for clothes and, finally, a charge of 12 baiocchi for dismantling the whole edifice.

Ippolito adapted with enthusiasm to the fashions of the papal court, in particular to the current revival of interest in antiquity. He bought antique medals and started his collection of ancient sculpture with a head of the Emperor Vitellius, which he bought for 20 scudi – he would later own one of the best collections of antiquities in Rome. He also commissioned two sculptors to make a bronze copy of the classical statue of the Spinario on the Capitol, which he intended as a present for Francis I, and he paid the craftsmen an advance of 100 scudi for their work. Both these deals were arranged by Cellini who, we can be sure, profited handsomely from them.

Ippolito also decided to rent a villa. The fashion for suburban villas on the hills above the sixteenth-century city had been inspired by the literature of ancient Rome and its descriptions of a cultured elite retiring from the pressures of urban life to rest and entertain in a peaceful rural setting where the fresh air provided a welcome contrast to the noise and smells in the streets below. The famous seven hills of Rome were largely uninhabited now and the land was cultivated as orchards and vineyards, or used as grazing for cattle and sheep. Ippolito rented a villa on the Quirinal, which rose behind the church of Santi Apostoli, conveniently close to his palace. Though modest in size, it had a superb position, with views east across orchards and fields to the Colosseum, and south over the city itself. Ippolito spent 42 scudi making improvements to the gardens, and he enjoyed the setting so much that he later built his own sumptuous villa on the same hill.

![]()

Ippolito was spending liberally and inevitably he ran out of money. Although his lawyer had finalized the issue of bulls for all his benefices, it took some time for his income to come through – the revenues from Milan did not start until April, and he had to wait until May to receive the first instalments from his French benefices. ‘It is hugely expensive here,’ he wrote to his brother on 10 January, ‘and I cannot economize very easily because I have to maintain myself and my household at this court where everything is so expensive.’ He went on to explain precisely why economies were impossible: ‘I need to maintain the expenses of the way of life I have begun, because it seems to me that this is appropriate to my rank and position, and, being a brother to you, it also reflects on your honour, so please lend me some more money.’ Conspicuous expenditure was expected of the rich and powerful, and the lack of ready cash was no excuse. ‘If I do not have enough money, I shall be forced to borrow.’ Ippolito was understandably reluctant to resort to moneylenders in Rome, who were taking advantage of the economic situation and charging exceptionally high interest rates. One of his valets had pawned his expensive black velvet saglio in November for 7 scudi and Ippolito had repaid the loan. The interest charge for seventy days, which came to 84 baiocchi, worked out at an annual rate of 60 per cent.

Life in Rome was expensive, and particularly so that winter. As a result of the appalling weather during the 1539 harvest, famine was now widespread across Italy. In Ferrara, the poor harvest of 1537 had raised the price of flour to 11 soldi a peso (over 8½ kilos), but by November 1539 the price had risen to 28 soldi. In Rome, where wheat was measured in rubbia (1 rubbio was equivalent to 2.3 hectolitres), grain prices were also rising. Ippolito paid 8 scudi a rubbio for wheat in January and 9 scudi in February. The poor, as usual, suffered the most. Paul III ordered each of the cardinals in Rome, including Ippolito, to contribute 25 scudi a month to a fund which he distributed among the poor. In January Ippolito wrote to his brother, ‘I have pity and compassion for these poor needy people, who multiply here every day.’ But the poor were also a nuisance, and he complained that he was jostled by crowds of beggars ‘demanding money, so that when I go to Consistory, they do not leave me space to mount my mule’. There were disadvantages to looking rich, and Ippolito felt sufficiently threatened by the violent atmosphere in Rome to buy a small dagger.

Item |

Scudi |

% |

Wheat |

1,052 |

25 |

Wine |

862 |

21 |

Butcher |

292 |

7 |

Poulterer |

77 |

2 |

Fishmonger |

533 |

13 |

Spice merchant |

278 |

7 |

Grocer |

277 |

7 |

Greengrocer |

29 |

1 |

Advances to purveyor |

380 |

9 |

Firewood |

234 |

5 |

Candles |

32 |

1 |

Laundry |

24 |

1 |

Water carrier |

3 |

– |

Miscellaneous |

33 |

1 |

Total |

4,106 |

|

Living in Rome, January-March 1540

The surviving ledgers make it possible to be precise about the cost of living in Rome that winter, and to show just how expensive it was for Ippolito to maintain an entourage of 100 men. In the first three months of 1540 he spent 4,101 scudi on food, wine and other household essentials such as candles and firewood, or an average of over 13½ scudi per man per month. That was nearly three times the amount he had spent on the same items in Lyon in April 1536 (see table on p. 99).

Not included in the table above is the cost of maintaining Ippolito’s horses. Orabon’s ledger records a total of 1,057 scudi spent on fodder supplied between January and March, an average monthly bill for each horse of 3½ scudi, or 42 scudi a year, again considerably more than he had paid in France.

Wheat was easily the most expensive item in Ippolito’s outgoings and accounted for just over 25 per cent of the total, but surprisingly this was only marginally more than he had spent in Lyon. Nearly everything was more expensive in Rome – eggs in particular. In Lyon a scudo would buy 450 eggs, but in Rome only 100. On the other hand, oranges, which were grown locally, were significantly cheaper – you could buy 1,050 for a scudo in Rome, but only 270 in Lyon.

The one area where there was a significant difference in the percentage that Ippolito spent on items was in the spice merchant’s bills – 7 per cent in Rome compared to only 1 per cent in Lyon – and there was a good reason for this. These merchants also supplied medicines, and nearly 150 scudi of the total bill was spent on ‘medicines, syrups and other similar things for those who were ill’. Rome’s climate was notoriously unhealthy. Niccolò Tassone was in such poor health that Ippolito gave him permission to go home to Ferrara, and one of the pages, Tebaldo Lampugnano, a relative of Ippolito’s mistress Violante, fell seriously ill in November. He had to be nursed by a Madonna Lucretia in her own house for ‘three months and seventeen days’, as Orabon precisely recorded on 18 March, when he paid her the final instalment of 10 scudi for her labours. In his ledger Morello referred to another ailing page who was given twelve small birds to tempt his appetite, and he also detailed several purchases of kids specifically for the sick. Ippolito himself seems to have been ill in early March, when Zudio bought a length of red flannel to make a compress for his stomach, while Tomaso Mosto had a bad arm and took 5 metres of orange taffeta from the wardrobe to make a rather expensive, and colourful, sling.

![]()

Lent in Rome was austere. Ippolito curtailed his regular Wednesday evening dinner parties, and there is not a single entry in his gambling book for this period. However, in the middle of March he received a welcome letter from Francis I, asking him to return to France. Ippolito was flattered and excited. ‘I will show you the letter itself when I arrive’, he wrote to Ercole, informing him that he was leaving Rome without delay and would stop off in Ferrara on his way to Fontainebleau, ‘and you will see how affectionately the King has called me to France.’ He added, no doubt to justify his departure, that Francis I had promised that his return to France ‘will be of profit to our house’, and he immediately dispatched one of his valets, Alessandro Rossetto, with a letter for Francis I announcing his impending return. The letter was sufficiently urgent for Ippolito to pay the substantial cost of post horses for Rossetto. The valet left on 16 March with 160 scudi to cover his travel expenses, and plenty of warm clothes for the journey across the Alps.

Ippolito’s sudden decision to leave Rome meant a lot of extra work for his household. In addition to an enormous amount of packing, there were bills to pay and supplies to buy for the journey. Zerbinato settled all the bills with Ippolito’s contract suppliers. Morello bought rope, lamp wicks, writing paper, a large quantity of candles, twenty-three wine flasks and 1,000 toothpicks. He also paid for the laundering of 1,054 tablecloths on 18 March, settled the bill of Paul III’s apothecary for two flasks of syrup for those members of the household who were still ill, and reimbursed Andrea the cook for sharpening all the kitchen knives.

It was decided to split the household in half, with one party travelling directly to Ferrara via Florence, while Ippolito and the other men made a detour via Loreto, where Ippolito wanted to visit the shrine of the Virgin. The Florence party comprised fifty men, nine of whom were too ill to ride and had to travel in a cart. They took with them all the heavy luggage, including the furniture and tapestries sent down from Ferrara to decorate Cardinal Gonzaga’s palace, though they left the mattresses and bedding behind, as well as Ippolito’s bed hangings. Panizato, who took charge of this party, spent 346 scudi hiring teams of mules, muleteers and their wagons from innkeepers in Rome and Florence, and another 265 scudi on food and accommodation for the party. Morello, who travelled via Loreto with Ippolito and the other fifty men, and eight mules, spent only 218 scudi on the journey. Cellini, who was also going to Ferrara, refused to travel with the Florence party and insisted on making his own arrangements – according to his own account, he wanted to visit some cousins who were nuns in Viterbo. Mosto gave him 10 scudi to cover his expenses, but they proved inadequate, and when he caught up with the party in Florence, Panizato had to give him another 10 scudi.

On Monday, 22 March, Ippolito made his formal exit from Rome, throwing coins to the poor as he left. The party crossed the Tiber by the Milvian bridge, the site of Constantine’s victory over his rival Maxentius in AD 312, and headed north. They spent the first night at Rignano, about 40 kilometres north of Rome, and the next day headed up the Via Flaminia and into the Apennines. Among the party were Ippolito’s courtiers, Romei, Alamanni, Mosto (still wearing his orange taffeta sling), Parisetto, Antoine the tailor, Morello and Ippolito d’Argenta, the footman who distributed Ippolito’s alms. Carnevale, one of the Chamber servants, had the unenviable task of travelling with the mules several days behind. On Good Friday they arrived at Tolentino where Ippolito visited the basilica of St Nicholas of Tolentino, a thirteenth-century Augustinian hermit much venerated for his charitable work, especially with plague victims. Argenta tipped 5 scudi to the friar who heard Ippolito’s confession that day and gave another 4 scudi to the friar who showed him the relic of St Nicholas’ head (Ippolito went to confession just once more in 1540, when he celebrated the feast of All Saints in Paris with Francis I). The following day, Ippolito arrived in Loreto, where he spent two nights. He needed his rochet and soutaine on Easter Day, but they were in the luggage travelling with the mules. Mosto had to hire a horse and cart from the innkeeper so that Antoine the tailor could ride back down the road and collect the garments. Ippolito made several visits to the shrine in Loreto, and Argenta left 10 scudi in alms, as well as giving ½ scudi to the doorkeeper and distributing coins worth 1 scudo to the poor in the streets outside.

Once again Ippolito and his entourage fell into the familar and regular routine of the road, spending the five nights of the journey from Rome to Loreto in taverns at Rignano, Narni, Spoleto, Serravalle and Tolentino. At Spoleto they lodged at The St George, which was run by a Ferrarese innkeeper who received an unusually high tip of 1 scudo. For breakfast the next morning, the three footmen were provided with a jug of wine and four bread buns each, while Ippolito and his men ate capon, thrushes and salad, washed down with eighteen jugs of wine (the same men had drunk forty jugs of wine the night before). Like his predecessor Zoane da Cremona, Morello spent his evenings buying food for Ippolito’s dinner, as well as supplies for the journey. Every transaction was recorded in his ledger, as were the exchange rate of each currency. The ledger was checked, and signed, every day while they were travelling by Parisetto the steward. It was still Lent, and the diet was mainly fish, but Morello also bought kid most days. At Serravalle he had to pay for broken plates, as well as the usual charges for firewood and candles. On Easter Day in Loreto the party feasted on lamb, capons, pigeon, eggs, cheese, almonds and salad. Morello had to hire napkins and tablecloths for the meal, and he also bought an extra jug of oil to rub into the horses’ hooves.

His religious duties completed, Ippolito left Loreto on Monday morning and, for the rest of the journey back to Ferrara, stayed with friends and family. He spent that night at Ancona as the guest of Leonello Pio da Carpi, a kinsman of the Cardinal, who entertained him in impressive style, staging a masque for his benefit. The next morning Ippolito handed out 22 scudi in tips to Leonello’s musicians and dining staff, a sum that included a very handsome tip of 10 scudi for the organizer of the masque. He then spent three nights in Pesaro at the court of his cousin, Guidobaldo della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, where the entertainment was primarily musical. Ippolito dispensed 18 scudi in tips to the cooks, the credenzieri and the other dining staff, and gave lengths of black velvet, worth about 26 scudi, to two musicians, a lutist and a clavichord player, who had evidently impressed him. They finally reached Ferrara on 8 April, several days later than the party that had travelled via Florence, to find the household frantically busy preparing for the journey to France.

![]()

At the Palazzo San Francesco, Julio Bochabella prepared eight pairs of Ippolito’s gloves, Zudio ordered more soap to wash Ippolito’s sheets and shirts, and Jacopo the barber bought six new towels as well as several jars of citrus and jasmine oils for Ippolito’s beard. Andrea, the servant to the pages, bought new leather boots and shoes for his charges and a leather case for their supplies, complete with an iron padlock, and stocked up on shoelaces. Diomede Tridapalle, the recently promoted valet, was reimbursed for mending two black velvet saglii and for buying new leather boots and shoes. In the stables Pierantonio organized a team of mules, muleteers and wagons to cart all the luggage to Lyon. He also bought several new horses, and swapped a mule called Bimbo for one called Albertino.

In the wardrobe Mosto was extremely busy. Ippolito wanted presents for the French court, and Mosto commissioned embroidered nightcaps, handkerchiefs and fine white linen shirts from several different seamstresses. There is no mention in the ledger of Sister Serafina, who had done Ippolito’s embroidery in the past – perhaps her eyesight had deteriorated with age. Ippolito also needed new clothes, though now that he had left Rome he no longer intended to wear ecclesiastical garb. Mosto ordered two pairs of leather boots and two pairs of black velvet shoes alla spagnola from Dielai the cobbler, and paid a woman to mend seven of Ippolito’s white linen shirts. He also bought Ippolito a new pair of black velvet breeches with matching hose, while Antoine the tailor sewed day and night. He made Ippolito three new overcoats – one in black velvet lined with black taffeta, and two of dark red damask – and a splendid outfit in dark red damask which Ippolito wanted to give to his cousin, the new Cardinal Enrique Borgia.

Ippolito bought himself two new weapons, an arquebus and a sword, neither of them particularly appropriate for a cardinal. The sword had an elegant silvered hilt and a scabbard lined with black velvet. The arquebus, which was ornately inlaid, had been made specially for him in Cremona. Mosto commissioned a holster for the gun, made of red leather imported from Brabant, together with two gilded powder flasks, which were covered in green velvet and decorated with green silk tassels and buttons.

During that fortnight, Mosto took delivery of several large consignments of textiles and other luxury goods sent from Venice by Ridolfo Campeggio. They cost 542 scudi and included 50 metres each of black satin, dark red satin and dark red damask, slightly shorter lengths of scarlet satin and scarlet damask, a silk carpet, and ambergris and musk to perfume Ippolito’s gloves. Also stored in the wardrobe during that fortnight was a valuable ornamental collar, embroidered in gold and red silk, and two expensive rosaries, all made in Mantua. These were payments in kind from one of Ippolito’s gambling partners, who owed him 113 scudi, and Ippolito intended to give them to ladies at the French court as presents.

At a more mundane level, Mosto ordered a new pair of linen sheets for Ippolito and bought 100 cheaper sheets for the household to replace those left behind in Rome. He also bought Ippolito a new camp bed. This was no utilitarian affair but a substantial four-poster bed in walnut that could be dismantled for travelling. In addition the same carpenter made a walnut chest for Ippolito’s antique medals and a round case for his linen. In fact Mosto’s ledger detailed a lot of new luggage. Ercole the saddler covered several flat wooden cases with black leather for transporting the Spanish leather wall hangings, and others with red leather for the tapestries. He also covered several boxes with green leather to hold supplies for the credenzieri and the sommeliers. Finally he made two cases for the Chamber: one for Ippolito’s chapel set, the other for his soap.

Cellini was not in the party setting out for France. Ippolito wanted him to stay in Ferrara to finish the jug and basin, and he gave him several more commissions to keep him busy over the summer, including a bronze portrait medal. Cellini set up his workshop in a room at Belfiore, furnished at Ippolito’s expense with the tools and materials he needed. Orabon recorded the itemized bills sent in for a large table, a whetstone, pitch, soldering wire and lead, and the day before Ippolito left for France, Mosto gave Cellini an old candlestick and 16 scudi in coins, which the goldsmith was to use to make the jug and basin. Cellini remained at Belfiore for the summer and, according to his own account, worked hard on the jug and basin, the medal and an official seal which Ippolito needed as a cardinal. However, he soon got bored and amused himself by taking potshots at the peacocks in the garden. (Ippolito finally summoned him to France that autumn, where he was given gold coins from the cardinal’s gambling profits to gild the jug and basin. They were ready in time for Christmas when Ippolito presented them to Francis I.)

![]()

The new Cardinal left Ferrara on 20 April. The fine spring weather promised a very different journey to the one he had made four years before. He must have been excited at the prospect of returning to his friends at the French court. He was also to be enthroned as Archbishop of Lyon on the way – the date had been fixed for 17 May.

Ippolito and his household travelled more quickly than they had done four years before, and they took a slightly different route, heading north to Mantua, where they spent two nights with Ippolito’s cousin, Federigo Gonzaga, and on to Turin. In Mantua, Ippolito spent 272 scudi on more presents for the French court, buying a new sword with a gilded hilt, several musk-perfumed rosaries with gold beads, and ten pairs of silk stockings. In Cremona Assassino bought bullets for the arquebus and Michiel, one of the boy sopranos, broke his collarbone. The next day they reached Casalpusterlengo, where they were met by Paulo Albertino, Ippolito’s agent in Milan, who arrived with 600 scudi due to Ippolito from the diocese. That same day, a courier rode in from Ferrara with 1,400 scudi sent by Fiorini. At Pavia, the second city of the duchy of Milan, Ippolito handed out 3 scudi in alms to several monasteries, and on 30 April, when they arrived in Turin, Zudio paid a laundress to wash eleven of Ippolito’s shirts. Turin was now in French hands, and Ippolito stayed with the governor for the May Day festivities, reporting to his brother that he had seen ‘a beautiful show’ and adding that the people ‘all seem to like the King’.

Ludovico Morello’s ledger for the journey has not survived, so we know nothing about the inns they stayed in or the food they ate, but the tips and alms handed out on Ippolito’s behalf were all recorded by Orabon. In the eleven days they were on the road, Ippolito dispensed 15 scudi in alms and 230 scudi in tips. The tips were given to all sorts of people – 10 scudi to a group of boys who sang for Ippolito on the road, 1 scudo to a monk in Mantua who gave him a basket of lemons, 1 scudo each to the fifty-five musicians who played for him while he was staying with Federigo Gonzaga, and 1 scudo to the innkeeper of The Three Kings at Pavia, where he stayed the night. There were also numerous tips to couriers, to guides and to the men who ferried the household across the numerous rivers that flowed down from the Alps into the Po.

Ippolito left Turin on 2 May and crossed the Mont-Cenis pass into France. The journey over the pass was a great deal easier than it had been over the Col d’Agnel (though this time he bought leather shoes to protect his dogs’ feet). Once in France he was greeted in every village by young girls dressed as May Queens, singing and celebrating the arrival of the summer. He also started gambling again. Apart from the record of the expensive collar and rosaries that one of his debtors had sent to repay the 113 scudi he owed Ippolito in April, there had been no entries in his gambling book since the beginning of the year.

Ippolito’s enthronement as Archbishop of Lyon was now only a fortnight away, and Antoine had still not finished the clothes that Ippolito’s entourage would wear for his official Entry into the city. Antoine and Orabon were sent on ahead to Lyon with two crates filled with silks and velvets from the wardrobe. In Lyon Antoine started work on new garments for the six footmen, ten pages and three boy sopranos. The footmen needed doublets of grey velvet striped with orange and white, which they would wear with orange taffeta breeches, red hats and grey hose decorated with orange taffeta and threaded with strips of white cloth. Orabon commissioned two wooden shields decorated with Ippolito’s coat-of-arms for the footmen to carry in the procession. Next on the list were the pages and the boy sopranos. Antoine made saglii for them, also in grey velvet threaded with Ippolito’s colours, which they would wear with the orange satin doublets that the tailor had made during the fortnight in Ferrara, while Orabon bought them white leather boots, breeches and hose – grey, orange and white for the pages, and red for the boy sopranos. Finally there were the valets, who were to wear orange satin doublets over black breeches, and hose threaded with strips of black satin.

![]()

Ippolito arrived at the gates of Lyon on Sunday, 16 May, where he was met by civic officials and escorted to his lodgings for the night. He was put up in a house called La Guillotière – Orabon referred to it in his ledger as La Gioletiera – then a small village outside the city gates and now a suburb to the east of the Rhône. The following day he made his ceremonial Entry into Lyon, riding a mule and accompanied by his entourage, all splendidly dressed by Antoine. The procession crossed the bridge over the Rhône, guarded by its formidable gatehouse, then made its way through the city streets and across the Saône to the city’s imposing twelfth-century cathedral. As Ippolito dismounted, his mule’s tail was ceremonially docked, a privilege for which Ippolito had to pay 100 scudi – Orabon laconically recorded in his ledger that ‘this was the custom of the place and earlier archbishops had established the price for this service’. Inside the cathedral he was installed with magnificent pomp as the new Archbishop. Ippolito loved the ceremony and all the theatrical and musical entertainments that had been organized for him. In striking contrast to his description of the long and tedious services he had endured when he was installed as a Cardinal in Rome, he wrote enthusiastically to Ercole, describing the beautiful decorations and festivities – ‘everybody was so happy I could not have wished for more’, adding that it was ‘thanks to God and to you, who I know will be as pleased as I am’.

Ippolito stayed only a week in Lyon, just long enough for his household to reorganize itself and hire another team of mules to transport the luggage north to Fontainebleau, and for Ippolito to be entertained once again by the ladies who rowed him across the Saône. Mosto used the time to commission a seamstress to hem five tablecloths and three dozen napkins, and to buy new leather boots for Pompilio Caracciolo, two of the pages and one of the boy sopranos, whose boots, new in Ferrara, had worn out on the journey. He also bought Ippolito a new pair of black velvet breeches and hose, decorated with silk fringes, which Antoine had to let out because they were too tight. The tailor now started work on a new set of bed hangings for Ippolito, made of the red satin that Mosto had brought from Venice and embellished with silk fringes and gilded sequins bought specially in Milan. The hangings were lined with expensive rose-coloured Florentine taffeta and sewn with silk thread purchased from a haberdasher called Matheo Paris.

While his household worked, Ippolito spent his time paying official visits and dispensing alms – 20 scudi to the Hôtel-de-Dieu, the city’s hospital, 6 scudi to the cathedral priests and 1 scudo in coins to the poor. He also handed out tips worth 53 scudi to buffoons, musicians, including a group of Italian viola players, and the lady bargees. On 21 May, Tomaso del Vecchio delivered 4,000 scudi to Mosto, revenues from Ippolito’s abbeys of Jumièges and St-Médard which were owed from 1539. Ippolito’s financial problems were beginning to recede. He left Lyon the next day, reporting to his brother that ‘everyone here has tried to persuade me to stay, but I have had letters from Rossetto in which he repeats that the King is most anxious that I go to court’.

On the journey through the Loire valley, Ippolito suddenly decided that he required new clothes for his arrival at court. In particular, he wanted two coats of red damask, one short and one long, and both with wide French sleeves. There was not enough red damask in the wardrobe for both garments, so Antoine the tailor was dispatched to Paris with post horses to buy the extra materials needed, and to make the garments. He was then to ride back south again to meet them before they arrived at Fontainebleau.

Early on the morning of 29 May, Antoine set off with two crates of materials and a guide. Shortly after leaving, one of the crates broke open and he had to buy nails to repair it. Then the next day he had to stop again because the ropes holding the crates had begun to fray and needed replacing. It took him three days to cover the 315 kilometres to Paris, and he changed horses eighteen times. He got to Paris on Tuesday, 1 June – Ippolito was at La Charité-sur-Loire that night, having covered only 107 kilometres in the past four days – and went straight to the shop of Philippe Legie, a prosperous textile merchant, who charged him 51 scudi for some red Venetian damask and another 14 scudi for several smaller pieces of velvet and taffeta. For the next three days Antoine sewed and sewed, and on the Thursday he had to return to Legie’s shop for more supplies. On Saturday he left Paris and rejoined the household at Nemours, about 80 kilometres south of Paris, bringing the finished clothes with him.

For the footmen Antoine had made six Spanish-style coats in grey cloth, decorated with wide stripes of orange velvet and threaded with rings of white taffeta. He charged Ippolito over 7 scudi for these garments, which suggests that they involved a lot of work, but only 2 scudi for the three coats he had made for the boy sopranos, which were of red cloth, bought from Legie for 10 scudi and trimmed with black velvet from the wardrobe. Antoine had also found time to make a black fustian doublet for the pastry cook and a new orange satin doublet for one of the pages. Ippolito’s clothes were decidedly not those of a cleric. Antoine had made two doublets, one in red Venetian satin and the other in finely pleated red Florentine taffeta. There were two new saglii, one in brown velvet trimmed with red taffeta for riding, and the other in red Venetian damask also trimmed with red taffeta, which was clearly intended for social occasions. Finally there were two new coats, both of red damask: the long coat had wide French-style sleeves, while the short one was edged with brown velvet and lined with red taffeta. Antoine had also trimmed a brown velvet hat with red taffeta and peacock feathers. Ippolito must have looked splendid, and very expensive – the cost of the materials for these garments came to 210 scudi.

Ippolito arrived at Fontainebleau on 6 June and his enthusiastic reception by the French court was graphically described by Ercole’s ambassador.

He found the King was still in bed and as soon as he had dismounted, without quenching his thirst, he went straight to the King’s bedchamber, where the ushers allowed him to enter, and the King was extremely pleased to see him – so it is said, though no one else was in there with them – and Ippolito stayed with him for two hours. The King then rose, gave Ippolito permission to go back to his own chambers and asked him to return to lunch. When Ippolito left the King’s bedchamber he went to that of Catherine de’ Medici, who had only just got up – I was with him and saw she was overjoyed to see him. Both of them went to the room of Madame d’Etampes, who was still in bed, and they were warmly welcomed and spent half an hour with her. He then went to visit the Queen and Princess Marguerite, and to the audience chamber where he saw the Queen of Navarre and the Cardinal of Lorraine. When he got back to his chambers he was visited by Cardinal Tournon and others, then he changed and went to Mass with the King. Afterwards they had lunch together alone. The Cardinal of Lorraine lunched with Madame d’Etampes and the King of Navarre lunched with the Chancellor. Montmorency was away the day Ippolito arrived, but when he returned he greeted Ippolito as warmly as the others.

Ippolito had returned laden with presents for the court. They were graded according to the status of the recipient and were distributed by Alessandro Rossetto over the following month. On 10 June, Rossetto presented Ippolito’s gifts to Queen Eleanor and to Marguerite, Francis I’s only surviving daughter. The Queen received two ornamental collars, embroidered with gold and red silk, one of which had been made in Mantua and the other in Milan. The Mantuan collar was one of the items Ippolito had received in April in lieu of a gambling debt. For Marguerite, Ippolito had brought two pairs of orange velvet slippers embroidered with silver thread, two pairs of matching stockings and a peacock-feather fan. A few days later it was the turn of Madame d’Etampes, the King’s mistress. Rossetto presented her with two pairs of perfumed gloves, a pair of fine linen sleeves embroidered with gold and green silk, two embroidered linen nightcaps and six linen handkerchiefs, three of which were embroidered with gold and green silk, three with gold and red silk. For the Cardinal of Lorraine Ippolito had brought two fine linen shirts, which had been embroidered in Ferrara with dark red silk, and twelve matching linen handkerchiefs. The Duke of Orléans received a pair of perfumed gloves and three linen nightcaps, worked with gold, scarlet, dark red and green silks. For the Dauphin Ippolito had a fine sword with a hilt ornamented with silver, which he had bought in Mantua. A month later the Dauphin gave Ippolito a superb chestnut horse and paid the new Cardinal the striking compliment of having the gift presented by his personal squire – Ippolito tipped the squire the enormous sum of 70 scudi, an amount that reflected Ippolito’s pleasure at the honour done to him by the Dauphin, and his delight at receiving such a handsome animal. For the King Ippolito had only the promise of Cellini’s jug and basin, and the copy of the Spinario, neither of which were ready, but he gave him his own sword with its beautiful silver Spanish-style hilt because, as Orabon succinctly noted in his ledger, ‘the King asked for it’.

There is no mention in the ledgers of what he gave Catherine de’ Medici or the Queen of Navarre, nor St-Pol, who presented Ippolito with fourteen dogs, including two prized Brittany hounds, a week after his arrival. Nor is there any mention of a present for Montmorency who gave Ippolito a magnificent mule when he returned to court. There were, however, several presents for Ippolito’s favourites among the ladies-in-waiting. One married lady received four pairs of silk stockings, while another, unmarried and evidently a particular favourite, was given two embroidered nightcaps, a pair of embroidered sleeves, a pair of perfumed gloves, a peacock-feather fan and one of the musk-perfumed rosaries that Ippolito had acquired as part of that gambling debt.

A week or so after his return Ippolito received another token of Francis I’s friendship, and one that reminded him, with a most pleasurable emphasis, that he was back in an environment which suited his temperament far better than the male-dominated court in Rome. The King took Ippolito, together with the Cardinal of Lorraine and Montmorency, to visit Madame d’Etampes in her private apartments at Fontainebleau. They found her in her bath, and not alone. Also in the bath were Marguerite, Francis I’s 17-year-old daughter, and three ladies-in-waiting. All the women were naked, though only their breasts were visible above the water. The men were delighted and, according to the Ferrarese ambassador, who reported the incident, they ‘spent a long time joking with the ladies’. This was obviously a regular event, and probably engineered by Madame d’Etampes for the King’s entertainment. The ambassador showed no shock in his report, using the incident as proof that Montmorency was still in favour with the King – but it was also a sign that Ippolito himself had really arrived.