Dr. Joshua Worthy is chief of neurology at a large staff model health maintenance organization (HMO) and serves as the physician representative to the HMO’s executive committee. A national health plan has just been enacted that imposes mandatory cost controls. The HMO’s budget for the coming year will be frozen at the current year’s level. In past years, the annual growth in the HMO’s budget has averaged 12%.

The health plan CEO begins the committee meeting by groaning, “These cuts are draconian! To meet these new budget limits we’ll have to cut staff and ration life-saving technologies. Patients will suffer.” A consumer member responds, “We all know there’s fat in the system. Why, in the newspaper just the other day there was an article about how rates of back surgery in our city are twice the national average. And if we’re going to talk about cuts, maybe we should start by looking at your salary and the number of administrators working here. I’m not so sure patients have to suffer just because we’re adopting the kind of reasonable spending limits that they have in most countries.”

Dr. Worthy remains silent for much of the meeting. He wonders to himself, “Is the CEO right? Is cost containment inevitably a painful process that will deprive our patients of valuable health services? Or, could we be doing a better job with the resources we’re already spending? Is there a way that our HMO could implement these cost controls in a relatively painless fashion as far as our patients’ health is concerned?” Interpreting Dr. Worthy’s silence as an indication of great wisdom and judgment, the committee assigns him to chair the HMO’s task force charged with developing a cost control strategy to meet the new budgetary realities.

Concerns about the rise of health care costs dominate the health policy agenda in the United States. Another pressing health policy concern—lack of adequate insurance and access to care for tens of millions of people—is in part attributable to the problem of rising costs. Health care inflation has made health insurance and health services unaffordable to many families and employers.

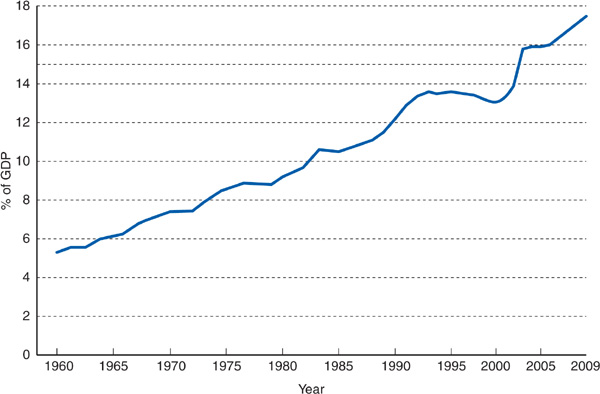

Private and public payers in the United States have taken aim at health care inflation and discharged volleys of innovative strategies attempting to curb expenditure growth, such as creating new approaches to utilization review, encouraging HMO enrollment, making patients pay more out-of-pocket for care, and a multitude of other measures. These approaches had little noticeable impact on the rate of growth of health care costs in the United States. National health expenditures per capita increased over sevenfold between 1980 and 2009, rising from $1110 to $8086 per capita (Figure 8–1). Viewed as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), US health expenditures increased from 9.2% in 1980 to 17.6% in 2009 (Figure 8–2). Health expenditures as a percentage of GDP are projected to rise to 19.6% by 2019 (Sisko et al, 2010).

Figure 8–1. US per capita health care expenditures. (Martin A et al. Recession contributes to slowest annual rate of increase in health spending in five decades. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:11.)

Figure 8–2. US health care expenditures as a percentage of the gross domestic product. (Martin A et al. Recession contributes to slowest annual rate of increase in health spending in five decades. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:11.)

Health care providers are discovering that they have to adjust to the prospect of practicing in an era of finite resources. Like Dr. Worthy, physicians and other health caregivers need to deliberate about how constraints on expenditure growth may affect patients’ health. Must cost control necessarily be painful, leading to rationing of beneficial services? Or, is there a painless route to containing costs, reached by eliminating unnecessary medical treatments and administrative expenses?

In this chapter, the painful–painless cost control debate will be explored. First a model will be constructed describing the relationship between health care costs and benefits in terms of improved health outcomes. Then different general approaches to cost containment and their potential for achieving painless cost control will be discussed. Chapter 9 will describe specific cost control measures in more detail.

Before entering medical school, Dr. Worthy worked in the Peace Corps in a remote area in Central America. At the time he first arrived in the region, the infant mortality rate was quite high, with many deaths due to infectious gastroenteritis. Dr. Worthy participated in the creation of a sewage treatment system and clean well-water sources for the region, as well as a program for implementing oral rehydration techniques for infants. By the end of Dr. Worthy’s 2-year stay, the infant mortality rate had dropped by nearly 25%. The cost for the entire program amounted to 15 cents per capita, paid for by the World Health Organization.

Conditions have been very different for Dr. Worthy as a practicing neurologist in the United States. In the past 5 years, over a dozen new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners have been installed in the city in which his HMO is located, an urban area with a population of 800,000. Dr. Worthy has found that MRI scans provide images that are better than those of computed tomography (CT) scans, allowing him to more accurately diagnose conditions such as multiple sclerosis in earlier stages. He is less certain about the extent to which these superior images allow superior health care for his patients.

From society’s point of view, the value of health care expenditures lies in purchasing better health for the population. The concept of “better health” is a broad one, encompassing improved longevity and quality of life, reduced mortality and morbidity rates from specific diseases, relief of pain and suffering, enhanced ability to function independently for those with chronic illnesses, and reduction in fear of illness and death. Thus, it is important to know whether investing more resources in health care buys improved health outcomes for society, and if so, what magnitude of the improvement in outcomes may be relative to the amount of resources invested.

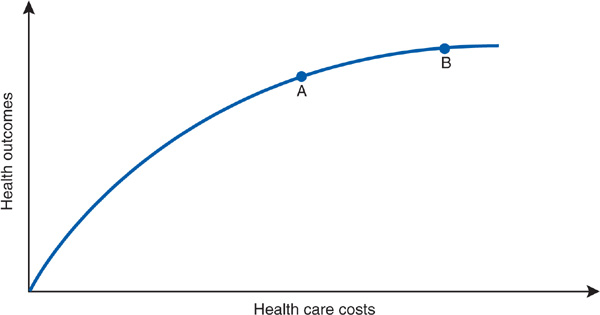

Figure 8–3, drawn from the work of Robert Evans (1984), illustrates a theoretic relationship between health care resource input and health care outcomes. Initially, as health care resources increase, these outcomes improve, but above a certain level, the slope of the curve diminishes, signifying that increasing investments in health care yield more marginal benefits. In terms of Dr. Worthy’s experiences, the Central American region in which he worked lay on the steep slope of this cost–benefit curve: A small investment of resources to create more sanitary water supplies and to administer inexpensive rehydration therapy yielded dramatic improvements in health. On the other hand, purchasing MRI scanners to supplement CT scanners represents a health care system operating on the flatter portion of the curve: Large investments of resources in new technologies may produce more marginal and difficult-to-measure improvements in the overall health of a population.

Figure 8–3. A theoretic model of costs and health outcomes. Moving from point A to point B on the curve is associated with both higher costs and better health outcomes.

Naturally, different medical interventions lie on steeper (eg, childhood immunizations) or on flatter (eg, the costly prolongation of life for an anencephalic infant) portions of the curve. The curve in Figure 8–3 may be viewed as an aggregate cost–benefit curve for the functioning of a health care system as a whole. The system may be an entire nation or a smaller entity such as an HMO, with its defined population of enrollees.

Overall, the US health care system currently operates somewhere along the flatter portion of the curve. Let us assume that Dr. Worthy’s HMO system lies at point A on the curve in Figure 8–3, with average total health care expenditures per HMO enrollee being the same as the average overall per capita health care cost in the United States (roughly $8000 in 2009). If stringent new cost containment policies forced the HMO to virtually freeze spending at point A rather than increasing annual expenditures at their usual clip to move to point B, then Figure 8–3 implies that the HMO would sacrifice improving the health of its enrollees by an amount equal to the distance between points A and B on the vertical axis.

Such an analysis would confirm the opinion of those who argue that cost containment requires painful choices that affect the health of the population. Among the most forceful proponents of this view are Aaron and Schwartz (1984 and 1990), who have described cost containment as a “painful prescription” requiring rationing of beneficial care. In Figure 8–3, the distance between points A and B on the y axis measures how much health “pain” accompanies the decision to limit spending at point A instead of advancing to point B. Some degree of pain is inherent in the curve. As Evans (1984) observes, “if its slope is everywhere positive, then in a world of finite resources, unmet needs are inevitable.” No matter where we sit on the curve, it will always be true that if we spent more we could do a little better.

In Figure 8–3, the distance between points A and B on the y axis is small, given the relatively flat slope of the curve at these points. But reassurances about relatively mild cost containment pain bring to mind the physician, scalpel in hand, hovering over a patient and declaring that “it will only hurt a little bit.” A little pain, necessary as it may be, is not the same as no pain; or as Fuchs (1993) puts it, “‘low yield’ medicine is not ‘no yield’ medicine.”

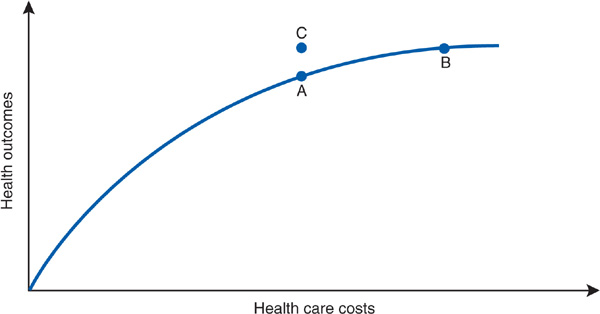

Before allowing ourselves (and Dr. Worthy) to become overly chagrined at the inevitable painfulness of cost containment, let us add the new dimension of efficiency. We can picture a point C (Figure 8–4) at which spending is the same as that at point A, but outcomes improve. How does the model account for point C, a point off the curve?

Figure 8–4. Moving off the curve. Point C represents achievement of better health outcome without increased costs.

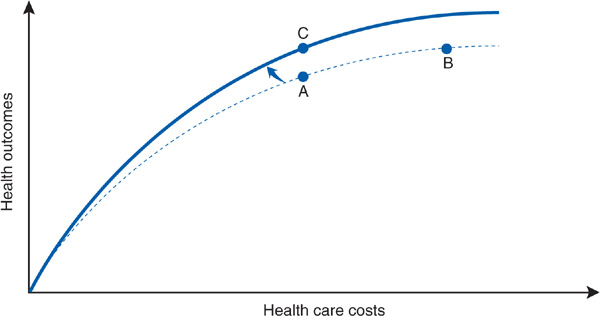

The move to point C requires a shifting of the curve (Figure 8–5), signifying a new, more efficient (or productive) relationship between costs and health outcomes (Donabedian, 1988). There are numerous possible routes to greater efficiency. For example, diagnostic radiographic imaging services are a rapidly inflating expenditure in the United States. Research has concluded that 20% to 40% of imaging studies are not clinically necessary, and that radiation exposure from diagnostic x-rays carries a risk of inducing malignant cancers (Brenner and Hricak, 2010). Eliminating unnecessary diagnostic radiographic procedures, such as head CT scans for patients with uncomplicated tension headaches, could simultaneously decrease health care costs and improve health. In the remainder of this chapter, we will examine in greater detail the various possible methods that Dr. Worthy’s cost control task force could consider to achieve more health “bang” for the health care “buck.” Before turning to this discussion, however, it is necessary to make explicit three assumptions about this model of costs and outcomes.

Figure 8–5. Shifting the curve. The shift of the curve represents moving to a more efficient relationship between costs and health outcomes.

1. Implicit in the model is the notion that the relevant outcome of interest is the overall health of a population rather than of any one individual patient. A number of authors have emphasized the need for physicians to broaden their perspective to encompass the health of a general population, as well as their narrower traditional focus on providing the best possible care for each patient (Eddy, 1991; Greenlick, 1992). The population-oriented model of costs and outcomes depicted in Figures 8–3, 8–4, and 8–5 may not fit easily with many physicians’ experiences of caring for a particular patient. At the level of the individual patient, the outcome may be all or nothing (eg, the patient will almost certainly live if he or she receives an operation and die without it) and not easily thought about in terms of curves and slopes. Rather than focusing on any one particular intervention or patient, the curve attempts to represent the overall functioning of a health care system in the aggregate for the population under its care. (The ethical issues of the population health perspective are discussed in Chapter 13.)

2. The model assumes that it is possible to quantify health at a population level. Traditionally, health status at this level has been measured relatively crudely, using vital statistics such as life expectancy and infant mortality rates. While an index such as infant mortality rates may be a sensitive, meaningful way of evaluating the impact of health care and public health programs in rural Central America, many analysts have questioned whether such crude indicators accurately gauge the impact of health care services in wealthier industrialized nations. In these latter nations, much of health care focuses on “softer” health outcomes such as enhancement of functional status and quality of life in individuals with chronic diseases—aspects more difficult to monitor at the population level than death rates and related vital statistics. In other words, it may be difficult to conceptualize a scale on the y axis of Figures 8–3, 8–4, and 8–5 that can register both the effects of managing gastroenteritis in a poor nation and the addition of MRI scanners in a US city.

3. When evaluating population health, it is difficult to disentangle the effects of health care on health from the effects of such basic social factors as poverty, education, lifestyle, and social cohesiveness (see Chapter 3). For the purpose of our discussion of cost control, we view the curves depicted in Figures 8–3, 8–4, and 8–5 as representing the workings of the health care system (including public health) per se rather than of the broader economic and social milieu. We therefore use the term health outcomes to describe the y axis, a term intended to suggest that we are evaluating those aspects of health status directly under the influence of health care. The x axis correspondingly represents expenditures for formal health care services.

We have shown that painless cost control is theoretically possible. But can efficiency be improved in the real world? What strategies could Dr. Worthy’s task force propose to move the HMO from point A to point C on the curve? An answer to these questions requires further scrutiny of resource costs in the health care sector.

Costs may be described by the equation

Price refers to such items as the hospital daily room charge or the physician fee for a routine office visit. Quantity represents the volume and intensity of health service use (eg, the length of stay in an intensive care unit, or the number and types of major diagnostic tests performed during a hospitalization). Lomas and colleagues (1989), noting this distinction between prices (Ps) and quantities (Qs), refer to cost containment as “minding the Ps and Qs” of health care costs.

Let us look at an example of the  equation:

equation:

Blue Shield pays Dr. Morton $600 for 10 office visits at a fee of $60 per visit. The next year, the insurer pays Dr. Morton $720 for 10 visits at $72 per visit.

Prudential pays Dr. Norton $600 for 10 office visits, and the next year pays $720 for 12 visits at the same $60 fee. An identical cost increase is a price rise for Dr. Morton but an increase in quantity of care for Dr. Norton.

Changes in prices and quantities have different implications for patients and providers (Reinhardt, 1987). In the preceding example, both physicians increase their income (and both insurance plans increase their expenditures) by $120, though in the case of the price increase, the additional income does not require a higher volume of work. To the patient, however, only the additional $120 spent on a greater number of visits purchases more health care services. (For simplicity’s sake, we assume that all visits are identical and that the price rise does not reflect increased quality of service, but simply a higher price for the same product.) A cost increase that merely represents higher prices without additional quantities of health care is an inefficient use of resources from the patient’s point of view. Returning to the diagrams in Figures 8–3 and 8–4, if real costs in a health care system were rising only because medical price inflation was exceeding general price inflation while the quantity of care per capita remained static, then increased health costs would not bring about improved health outcomes, and the overall curve would become absolutely flat.

After intense deliberation, Dr. Worthy’s task force submits a plan for “painless cost containment” to the HMO executive committee. The first proposal calls for the HMO to aggressively seek discounts on the prices paid for supplies, equipment, and pharmaceuticals by having the HMO selectively contract with suppliers for bulk purchases and stock a more limited variety of product lines and drugs within the same therapeutic class. The proposal also calls for a 10% reduction in salaries for all HMO employees earning over $150,000 per year, as well as a 10% reduction in the capitation fee paid to the HMO’s physician group. The executive committee never gets beyond this part of the plan, as furious argument erupts over the proposed income cuts.

Price inflation has been a major contributor to the rise of health care costs in recent decades. Between 1947 and 1987, US health care costs rose 2.5% per year faster than the growth in the overall economy. Two-thirds of this higher growth rate, or 1.6%, was due to health care prices rising more rapidly than prices in the overall economy. The remaining 0.9% differential was due to differences in the rate of increase of quantities of health care relative to increases in the overall quantity of goods and services (Fuchs, 1990).

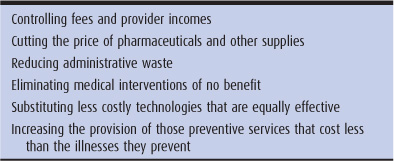

The rapid rise of health care prices manifests itself in such ways as prices for prescription drugs in the United States often being over 50% higher than prices for the same products sold in other nations. Also, specialist physician incomes have increased rapidly. Higher prices explain much of the higher costs of health care in the United States compared with the costs in other industrialized nations (Peterson and Burton, 2007). Limiting this type of price inflation is one way to restrain expenditures without inflicting “pain” on the public’s health (Table 8–1).

Table 8–1. Examples of painless cost control

After a brief hiatus to let the furor subside, the HMO executive committee reconvenes. Dr. Worthy introduces his task force’s second recommendation—developing appropriateness of care guidelines—by recounting one of his own clinical experiences. When Dr. Worthy first came to the HMO, the neurologists were keeping their stroke patients at bed rest for 1 week before initiating physical therapy. Dr. Worthy, in contrast, began physical therapy and discharge planning for stroke patients the moment their neurologic status was stable. The average length of stay in the acute hospital for his stroke patients was 3 days, compared with 9 days for other neurologists. Dr. Worthy gave a grand rounds presentation demonstrating that 4 days of exercise are required to regain the strength lost from each day of bed rest, meaning that stroke patients would have better outcomes and use fewer resources—shorter acute hospital stays and less rehabilitation—under his care than under the care of his colleagues. Dr. Worthy cites this as just one example of how the HMO may be devoting resources to ineffective, or even harmful, care.

If controlling prices is one approach to painless cost control, are there also ways to contain the “Q” (quantity) factor in a manner that does not sacrifice beneficial care? Earlier, we cited unnecessary diagnostic imaging studies as an example of a source of inefficient resource use in terms of quantities of services that add to costs without, in many cases, adding health benefits. A number of researchers have found convincing evidence of substantial amounts of unnecessary care in the United States (Brook and Lohr, 1986; Leape, 1992; Brownlee, 2007; Kilo and Larsen, 2009). Physicians in the United States perform large numbers of inappropriate procedures (Schuster et al, 1998; Deyo et al, 2009), and physicians may inappropriately and harmfully accept new technologies as a result of industry influence rather than proven efficacy (Grimes, 1993; Avorn, 2007).

Persuasive evidence comes from the work of Fisher, Wennberg and colleagues, who found that per capita Medicare costs are over twice as high in some cities (eg, Miami) than in other metropolitan areas (eg, Minneapolis). This difference is explained not by prices or degree of illness but is related to the quantity of services provided, which in turn is associated with the predominance of specialists in the higher-cost areas (Fisher et al, 2003). Moreover, residents of areas with a greater per capita supply of hospital beds are up to 30% more likely to be hospitalized than those in areas with fewer beds, after controlling for socioeconomic characteristics and disease burden (Fisher et al, 2000). As for the value of this spending, quality of care and health outcomes are, if anything, worse in the highest spending regions than in areas with less intensive use of services. These findings suggest that a great deal of unnecessary care is taking place in the high-cost areas.

The slope of the cost–benefit curve would become more favorable if a system could eliminate those components of rising expenditures that have flat slopes (no medical benefit) or negative slopes (harm exceeding benefit, as in the case of inappropriate surgical procedures or prolonged bed rest after strokes). However, inducing physicians and patients to selectively eliminate unnecessary care is no easy matter.

The third item on Dr. Worthy’s painless cost containment plan targets the HMO’s administrative costs. The task force proposes eliminating the HMO’s TV and radio advertising budget, laying off 25% of all HMO administrative personnel, and reassigning 25 of the 50 staff members in the department that handles contracts with employers to a new department designed to develop a program to ensure that the HMO provides up-to-date child immunizations and adult preventive care services for 100% of plan enrollees. The HMO’s marketing director patiently explains to Dr. Worthy that although he, in principle, agrees with these recommendations, he does not consider it in the HMO’s best interest to cut costs in a way that jeopardizes the plan’s ability to maintain its market share of enrollees.

Not all quantities in the health care cost equation are clinical in nature. The tremendous administrative overhead of the US health care system has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years as a source of inefficiency in health care expenditures. Woolhandler and colleagues (2003) have estimated that as many as 31 cents of every dollar of US health care spending goes for such quantities of administrative services as insurance marketing, billing and claims processing, and utilization review, rather than for actual clinical services. US administrative costs are over twice as high proportionately as those in nations such as Canada and have been rising more rapidly than the rate of overall national health care inflation. While some level of administrative service is necessary for health care finance management and related activities such as quality assurance, few argue that the burgeoning administrative and marketing activities translate into meaningful improvement in patient health. Reducing administrative services is another route to painless cost containment.

Eliminating purely wasteful quantities of health care services, be they ineffective clinical services or unnecessary administrative activities, is a relatively straightforward approach to painless cost control. The motto of this approach is: Stop doing things of no clinical benefit. More complicated are approaches to efficiency that involve not simply ceasing completely unproductive activities, but doing things differently. Examples of this latter approach include innovations that substitute less costly care of equal benefit, preventive care, and redistribution of resources from services with some benefit to services with greater benefit relative to cost. Let us examine each of these examples in turn.

Much of the process of innovation in health care involves the search for less costly ways of producing the same or better health outcomes. A new drug is developed that is less expensive but is equally efficacious and well tolerated as a conventional medication. Services provided by highly paid physicians can often be delivered with the same quality by nurses, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants. A clinical trial documents that infusion of chemotherapy for many cancer treatments may be done safely on an outpatient basis, averting the expense of hospitalization. Often new technologies are introduced in hopes that they will ultimately prove to be less costly than existing treatment methods.

However, new technologies often fail to live up to cost-saving expectations (Bodenheimer, 2005). A case in point is that of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Through the use of fiberoptic technology, the gallbladder may be surgically removed using a much smaller abdominal incision than that required for traditional open cholecystectomy, thereby significantly shortening the time required for postoperative recuperation in the hospital. The shorter length of hospital stay reduces the overall cost of the operation, with improved outcomes due to less postoperative pain and disability—seemingly a classic case of “efficient substitution” that lowers costs and improves health outcomes. There’s a catch, however. The necessity of gallbladder surgery is not always clear-cut for patients with gallstones. Many patients have only occasional, mild symptoms, and prefer to tolerate these symptoms rather than undergo an operation. Rates of cholecystectomy increased dramatically following the advent of the laparoscopic technique, apparently because more patients with milder symptoms were undergoing gallbladder surgery. In one HMO, the cholecystectomy rate increased by 59% between 1988 and 1992 after the introduction of the laparoscopic technique. Even though the average cost per cholecystectomy declined by 25%, the total cost for all cholecystectomies in the HMO rose by 11% because of the increased number of procedures done (Legorreta et al, 1993).

If an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, then replacement of expensive end-stage treatment with low-cost prevention would appear to be an ideal candidate for the “painless cost controller award.” Investing in prevention sometimes generates this type of efficiency in health care spending (eg, many childhood vaccinations cost less than caring for children with infections) (Armstrong, 2007). However, the prevention story is not always so simple. In many cases, the cost of implementing a widespread prevention program may exceed the cost of caring for the illness it aims to prevent. For example, screening the general population for elevated blood pressure and providing long-term treatment for those with mild-to-moderate hypertension to prevent strokes and other cardiovascular complications has been found to cost more than the expense of treating the eventual complications themselves (Russell, 2009). For some diseases, this is the case because the complications are rapidly and inexpensively fatal, while successful prevention leads to a long life with high medical costs, perhaps for a different illness, required at some point. Similarly a program of routine mammography screening and biopsy following abnormal test results costs more than it saves by detecting breast cancers at earlier stages. Blood pressure and breast cancer screening programs result in the improved health of the population but require a net investment in additional resources.

A fourth recommendation of Dr. Worthy’s task force involves the diagnosis and treatment of colon cancer. Many HMO physicians suggest screening colonoscopy for their patients over age 50 for early detection of colon cancer. All the HMO’s oncologists strongly recommend chemotherapy for patients who develop metastatic colon cancer. Analysis of cost-effectiveness has demonstrated that screening colonoscopy saves many more years of life per dollar spent than chemotherapy for metastatic colon cancer. Yet chemotherapy allows some patients with metastatic disease to enjoy an extra 6–12 months of life. The task force takes the position that the HMO’s physicians should do screening colonosco-pies, but that the HMO insurance plan should not cover chemotherapy for metastatic colon cancer.

The most controversial strategy for making health care more efficient is the redistribution of resources from services with some benefit to services with greater benefit relative to cost. This approach is commonly guided by cost-effectiveness analysis, which as defined by Eisenberg (1989).

… measures the net cost of providing a service (expenditures minus savings) as well as the outcomes obtained. Outcomes are reported in a single unit of measurement, either a conventional clinical outcome (eg, years of life saved) or a measure that combines several outcomes on a common scale. (Eisenberg, 1989)

An example is a cost-effectiveness analysis of different strategies to prevent heart disease, showing that the cost per year of life saved (in 1984 dollars) was approximately $1000 for brief advice about smoking cessation during a routine office visit, $24,000 for treating mild hypertension, and nearly $100,000 for treating elevated cholesterol levels with drugs (Cummings et al, 1989). In order to get the most “bang” for the health care “buck,” this analysis suggests that a system operating under limited resources would do better by maximizing resources for smoking cessation before investing in cholesterol screening and treatment.

Cost-effectiveness analysis must be used with caution. If the data used are inaccurate, the conclusions may be incorrect. Moreover, cost-effectiveness analysis may discriminate against people with disabilities. Researchers are likely to assign less worth to a year of life of a disabled person than does the person himself or herself; thus, analyses using “quality-adjusted life years” may have a built-in bias against persons with less capacity to function independently (Menzel, 1992).

Dr. David Eddy (1991, 1992, 1993), in a series of provocative articles in the Journal of the American Medical Association, has discussed the practical and ethical challenges of applying cost-effectiveness analysis to medical practice. Two of the essays involve the case of an HMO trying to decide whether to adopt routine use of low-osmolar contrast agents, a type of dye for special x-ray studies that carries a lower risk of provoking allergic reactions than the cheaper conventional dye. With the use of this agent for all x-ray dye studies, 40 nonfatal allergic reactions would be avoided annually and the cost to the HMO would be $3.5 million more per year, compared with costs for use of the older agent in routine cases and use of the low-osmolar dye only for patients at high risk of allergy. The same $3.5 million dollars invested in an expanded cervical cancer screening program in the HMO would prevent approximately 100 deaths from cervical cancer per year.

In discussing how best to deploy these resources, Eddy highlights several points of particular relevance to clinicians:

1. It must be agreed upon that resources are truly limited. Although the cost-effectiveness of low-osmolar contrast dye and cervical cancer screening is quite different, both programs offer some benefit (ie, they are not flat-of-the-curve medicine). If no constraints on resources existed, the best policy would be to invest in both services.

2. If resources are limited and trade-offs based on cost-effectiveness considerations are to be made, these trade-offs will have professional legitimacy only if it is clear that resources saved from denying services of low cost-effectiveness will be reinvested in services with greater cost-effectiveness, rather than siphoned off for ineffective care or higher profits.

3. Ethical tensions exist between maximizing health outcomes for a group or population as opposed to the individual patient. The radiologist experiences the trauma of patients having severe allergic reactions to the injection of contrast dye. Preventing future deaths from cervical cancer in an unspecified group of patients not directly under the radiologist’s care seems an abstract and remote benefit from his or her perspective—one that may be perceived as conflicting with the radiologist’s obligation to provide the best care possible to his or her patients.

Many analysts, including those who question the methods of cost-effectiveness analysis, share Eddy’s conclusion: Physicians must broaden their perspective to balance the needs of individual patients directly under their care with the overall needs of the population served by the health care system, whether the system is an HMO or the nation’s health care system as a whole (see Chapter 13). Professional ethics will have to incorporate social accountability for resource use and population health, as well as clinical responsibility for the care of individual patients (Greenlick, 1992; Hiatt, 1975).

The final recommendation of Dr. Worthy’s task force is for the HMO to hire a consultant to advise the HMO on the relative cost-effectiveness of different services offered by the HMO, in order to prioritize the most cost-effective activities. While waiting for the consultant’s report, the task force suggests that the HMO begin implementing this strategy by allocating an extra 5 minutes to every routine medical appointment for patients who smoke, so that the physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant has time to counsel patients on smoking cessation, as well as by setting up two dozen new community-based group classes in smoking cessation for HMO members. The costs of these new activities are to be funded from the HMO’s existing budget for coronary artery stenting, and the number of these stent procedures is to be restricted to 30 fewer than the number performed during the current year. The day following the executive committee meeting, the HMO’s health education director buys Dr. Worthy lunch and compliments him on his “enlightened” views. On the way back from lunch, the chief of cardiology accosts Dr. Worthy in the corridor and says, “Why don’t you just take a few dozen of my patients with severe coronary artery disease out and shoot them? Get it over with quickly, instead of denying them the life-saving stents they need.”

The relationship between health outcomes and health care costs is not a simple one. The cost–benefit curve has a diminishing slope as increasing investment of resources yields more marginal improvements in the health of the population. The curve itself may shift up or down, depending on the efficiency with which a given level of resources is deployed.

The ideal cost containment method is one that achieves progress in overall health outcomes through the “painless” route of making more efficient use of an existing level of resources. Examples of this approach include restricting price increases, reducing administrative waste, and eliminating inappropriate and ineffective services. “Painful” cost containment represents the other extreme, when controls on expenditures are accomplished only by sacrificing quantities of medically beneficial services. Making trade-offs in services based on relative cost-effectiveness may be felt as painless or painful, depending on one’s point of view; some individuals may experience the pain of being denied potentially beneficial services, but at a net gain in health for the overall population through more efficient use of the resources at hand.

Cost containment in the real world tends to fall somewhere between the entirely painless paragon and the completely painful pariah (Ginzberg, 1983). As the experiences of Dr. Worthy reveal, putting painless cost control into practice may be impeded by political, organizational, and technical obstacles. Price controls may make economic sense but risk intense opposition from providers. Administrative savings may be largely beyond the control of any single HMO or group of providers and require an overhaul of the entire health care system. Identifying and modifying inappropriate clinical practices is a daunting task, as is prioritizing services on the basis of cost-effectiveness. But while painless cost control may be difficult to achieve, few would argue that the US health care system currently operates anywhere near a maximum level of efficiency. Regions in the nation with higher health care spending do not have better health outcomes (Fisher et al, 2003). The nation’s lackluster performance on indices such as infant mortality and life expectancy rates suggests that the prolific degree of spending on health care in the United States has not been matched by a commensurate level of excellence in the health of the population (Davis et al, 2010). Making better use of existing resources must be the priority of cost control strategies in the United States.

Aaron H, Schwartz WB. Rationing health care: The choice before us. Science. 1990;247:418.

Aaron H, Schwartz WB. The Painful Prescription: Rationing Hospital Care. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 1984.

Armstrong EP. Economic benefits and costs associated with target vaccinations. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13(Suppl S-b):S12.

Avorn J. Keeping science on top in drug evaluation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:633.

Bodenheimer T. High and rising health care costs. Part 2: technologic innovation. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:932.

Brenner DJ, Hricak H. Radiation exposure from medical imaging. JAMA. 2010;304:208.

Brook RH, Lohr KN. Will we need to ration effective health care? Issues Sci Technol. 1986;3:68.

Brownlee S. Overtreated. New York: Bloomsbury; 2007.

Cummings SR et al. The cost-effectiveness of counseling smokers to quit. JAMA. 1989;261:75.

Davis K et al. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2010.

Deyo RA et al. Overtreating chronic back pain: Time to back off. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:62.

Donabedian A. Quality and cost: Choices and responsibilities. Inquiry. 1988;25:90.

Eddy DM. Applying cost-effectiveness analysis. JAMA. 1992;268:2575.

Eddy DM. Broadening the responsibilities of practitioners. JAMA. 1993;269:1849.

Eddy DM. The individual vs. society: Is there a conflict? JAMA. 1991;265:1446.

Eisenberg JM. Clinical economics. JAMA. 1989;262:2879.

Evans RG. Strained Mercy: The Economics of Canadian Health Care. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Butterworths; 1984.

Fisher ES et al. The implications of regional variation in medicare spending. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273.

Fisher ES et al. Associations among hospital capacity, utilization, and mortality of US Medicare beneficiaries, controlling for sociodemographic factors. Health Serv Res. 2000;34:1351.

Fuchs VR. No pain, no gain: Perspectives on cost containment. JAMA. 1993;269:631.

Fuchs VR. The health sector’s share of the gross national product. Science. 1990;247:534.

Ginzberg E. Cost-containment: Imaginary and real. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1220.

Greenlick MR. Educating physicians for population-based clinical practice. JAMA. 1992;267:1645.

Grimes DA. Technology follies: The uncritical acceptance of medical innovation. JAMA. 1993;269:3030.

Hiatt HH. Protecting the medical commons: Who is responsible? N Engl J Med. 1975;293:235.

Kilo CM, Larsen EB. Exploring the harmful effects of health care. JAMA. 2009;302:89.

Leape LL. Unnecessary surgery. Annu Rev Public Health. 1992;13:363.

Legorreta AP et al. Increased cholecystectomy rate after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JAMA. 1993;270:1429.

Lomas J et al. Paying physicians in Canada: Minding our Ps and Qs. Health Aff (Millwood). 1989;8(1):80.

Martin A et al. Recession contributes to slowest annual rate of increase in health spending in five decades. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:11.

Menzel PT. Oregon’s denial: Disabilities and the quality of life. Hastings Cent Rep. 1992;22:21.

Peterson CL, Burton R. U.S. Health Care Spending: Comparison with Other OECD Countries (RL34175) [Electronic copy]. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2007. http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/key_work-place/311/. Accessed November 14, 2011.

Reinhardt UE. Resource allocation in health care: The allocation of lifestyles to providers. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1987;65:153.

Russell LB. Preventing chronic disease: An important investment, but don’t count on cost savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:42.

Schuster M et al. How good is the quality of health care in the United States? Milbank Q. 1998;76:517.

Sisko AM et al. National health spending projections: The estimated impact of reform through 2019. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1933.

Woolhandler S et al. Costs of health care administration in the United States and Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:768.