In 2009, the United States spent $2.5 trillion on health care. Only 3% of this total was dedicated to government public health activities designed to prevent illness.

The renowned medical historian Henry Sigerist, writing in 1941, listed the main items that must be included in a national health program. The first three items were free education, including health education, for all; the best possible working and living conditions; and the best possible means of rest and recreation. Medical care rated only fourth on his list (Terris, 1992a). For Sigerist (1941), medical care was

A system of health institutions and medical personnel, available to all, responsible for the people’s health, ready and able to advise and help them in the maintenance of health and in its restoration when prevention has broken down. (Sigerist, 1941)

Many people working in the fields of medical care and public health believe that “prevention has broken down” too often; sometimes because modern science has insufficient knowledge to prevent disease, but more often because society has dedicated insufficient resources and commitment to prevention.

Primary prevention seeks to avert the occurrence of a disease or injury (eg, immunization against polio; taxes on the sale of cigarettes to reduce their affordability, and thereby their use). Secondary prevention refers to early detection of a disease process and intervention to reverse or retard the condition from progressing (eg, Pap smears to screen for premalignant and malignant lesions of the cervix, and mammograms for early detection of breast cancer).

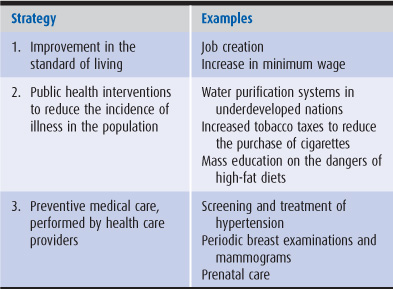

The promotion of good health and the prevention of illness encompass three distinct levels or strategies (Terris, 1986; Table 11–1):

Table 11–1. Strategies of prevention

1. The first and broadest level includes measures to address the fundamental social determinants of illness; as evidence presented in Chapter 3 shows, lower income is associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates. Improvement in the standard of living and social equity (eg, through job creation programs to reduce or eliminate unemployment) may have a greater impact on preventing disease than specific public health programs or medical care services.

2. The second level of prevention involves public health interventions to reduce the incidence of illness in the population as a whole. Examples are water purification systems, the banning of cigarette smoking in the workplace, and public health education on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention in the schools. These strategies generally consist of primary prevention. The 3% figure cited in the opening paragraph represents these public health activities.

3. The third level of prevention involves individual health care providers performing preventive interventions for individual patients; these activities can be either primary or secondary prevention. The US Preventive Services Task Force and other organizations have established regular schedules for preventive medical care services (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2010).

Until modern times, the conditions that produced the greatest amount of illness and death in the population were infectious diseases. The initial decline of infectious disease mortality rates took place even before the cause of these illnesses was understood. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, food production increased markedly throughout the Western world. By the early nineteenth century, infectious disease mortality rates were dropping in England, Wales, and Scandinavia, probably as a result of improved nutrition that allowed individuals, particularly children, to resist infectious agents. Thus, the initial success of illness prevention took place through the improvement of overall living conditions rather than from specific public health or medical interventions (McKeown, 1990).

In the nineteenth century, scientists and public health practitioners discovered many of the agents causing infectious diseases. By comprehending the causes (such as bacteria and viruses) and the risk factors (eg, poverty, overcrowding, poor nutrition, and contaminated water) associated with these illnesses, public health measures (such as water purification, sewage disposal, and pasteurization of milk) were implemented that drastically reduced their incidence. This was the first epidemiologic revolution (Terris, 1985).

From 1870 to 1930, the death rate from infectious diseases fell rapidly. Medical interventions, whether immunizations or treatment with antibiotics, were introduced only after much of the decline in infectious disease mortality had taken place. The first effective treatment against tuberculosis, the antibiotic streptomycin, was developed in 1947, but its contribution to the decrease in the tuberculosis death rate since the early nineteenth century has been estimated to be a mere 3%. For whooping cough, measles, scarlet fever, bronchitis, and pneumonia, mortality rates had fallen to similarly low levels before immunization or antibiotic therapy became available. Pasteurization and water purification were probably the main reason for the decline in infant mortality rates (McKeown, 1990).

Some illnesses are exceptions to the rule that infectious disease mortality is influenced more by improved living standards and public health measures than by medical interventions. Immunization for smallpox, polio, and tetanus and antimicrobial therapy for syphilis had a substantial impact on mortality rates from those illnesses. Considering infectious diseases as a group, however, medical measures probably account for less than 5% of the decrease in mortality rates for these conditions over the past century (McKinlay et al, 1989; McKeown, 1990).

As infectious diseases waned in importance during the first half of the twentieth century and as life expectancy increased, rates of noninfectious chronic illness grew rapidly. Eleven major infectious diseases accounted for 40% of total deaths in the United States in 1900, but less than 10% in 1980. In contrast, heart disease, cancer, and stroke (cerebrovascular disease) caused 16% of total deaths in 1900 but 64% by 1980 (McKinlay et al, 1989).

Fifty years ago, epidemiologists did not understand the causes of noninfectious chronic diseases.

Unable to prevent the occurrence of these diseases, we retreated to a second line of defense, namely, early detection and treatment—so-called secondary prevention. But secondary prevention has—with few exceptions—proved disappointing; it cannot compare in effectiveness with measures for primary prevention. The periodic physical examination, the cancer detection center, multiphasic screening, and a host of variations on these themes have incurred enormous expenditures for relatively modest benefits … Major exceptions are cancer of the cervix, for which early detection has proved dramatically effective, and, to a lesser extent, cancer of the breast.

Beginning in 1950, dramatic breakthroughs occurred in the epidemiology of the noninfectious diseases. During the next three decades, our epidemiologists forged powerful weapons to combat most of the major causes of death. In doing so, they initiated a second epidemiologic revolution, which, if we act appropriately, will result in an enormous reduction in premature death and disability. (Terris, 1992b)

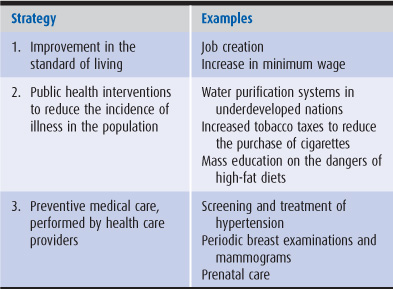

During the second epidemiologic revolution, it was learned that the major illnesses in the United States have a few central causes and are in large part preventable. In 2007, 2.4 million people died in the United States (Table 11–2). A surprisingly small number of risk factors are implicated in 37% of these deaths. It has been estimated that use of tobacco causes 435,000 fatalities, a high-fat diet and inactivity contributes to 365,000 more, and alcohol is responsible for 85,000 deaths annually in the United States (Heron et al, 2009; Xu et al, 2010). By discovering and educating the population about the risk factors of smoking, rich diet, and lack of exercise, the second epidemiologic revolution has already been very successful. From 1980 to 2006, age-adjusted mortality rates for coronary heart disease (CHD) declined by an astonishing 61%. This decline was associated with reduced rates of tobacco use and lowered mean serum cholesterol levels in the population. As with infectious diseases a century earlier, this decline was in substantial part related to public health interventions regarding smoking and diet (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). The unfortunate side of this success story is that those in the poorest socioeconomic position and the least education have considerably higher mortality rates than those with higher socioeconomic status (Loucks, 2009).

Table 11–2. Causes of death in the United States, 2007a

Chronic disease prevention may be viewed from two distinct perspectives: that of the individual and that of the population (Rose, 1985). The medical model seeks to identify high-risk individuals and offer them individual protection, often by counseling on such topics as smoking cessation and low-fat diet. The public health approach seeks to reduce disease in the population as a whole, using such methods as mass education campaigns to counter drinking and driving, the taxation of tobacco to drive up its price, and the labeling of foods to indicate fat and cholesterol content. Both approaches have merits but the medical model suffers from some drawbacks.

The individual-centered approach of the medical model may produce tunnel vision regarding the causation, and thus the prevention, of disease. Let us take the example of cholesterol.

Ancel Keys (1970) performed a famous study comparing CHD in different nations. In east Finland, CHD was common, 20% of diet calories came from saturated fat, and 56% of men aged 40 to 59 years had cholesterol levels greater than 250 mg/dL. In Japan, CHD was rare, 3% of calories were provided by saturated fat, and only 7% of men aged 40 to 59 years had cholesterol levels above 250 mg/dL. If we compared two individuals in east Finland who eat the same diet, one with a cholesterol level of 200 mg/dL and the other with a level of 300 mg/dL, we might conclude that the variation in cholesterol levels among individuals is caused by genetic or other factors, but not diet. If, on the other hand, we remove our individual blinders and look at entire populations, studying the average cholesterol level and the percentage of fat in the diet in east Finland and in Japan, we will conclude that high-fat diets correlate with high levels of cholesterol and with high rates of CHD.

Individual variations within each country are often of less importance than variations between one nation and another. The clues to the causes of diseases “must be sought from differences between populations or from changes within populations over time” (Rose, 1985).

The medical model may also target its interventions to the wrong individuals. Let us continue with the cholesterol example. In the United States, most people with high cholesterol levels remain healthy for years, and some people with low levels have heart attacks at an early age. Why is this so? Because the risk of CHD for persons with high cholesterol levels or low cholesterol levels is not so different; even for the low-risk individual, CHD is the most likely cause of death. Everyone in the United States is at risk for this disease. A “low” cholesterol level of 180 mg/dL is low by US standards, but high when compared with levels in poor nations. A large number of people at small risk for a disease may give rise to more cases of the disease than the smaller number of people who are at high risk (Brown et al, 1992). This fact limits the utility of the medical model’s “high-risk” approach to prevention. A public health approach (eg, mass educational campaigns on the health effects of rich diets and the labeling of foods) strives to reduce the mean population cholesterol level. A 10% reduction in the serum cholesterol distribution of the entire population would do far more to reduce the incidence of heart disease than a 30% reduction in the cholesterol levels of those relatively few individuals with counts greater than 300 mg/dL.

A coherent ideology underlies the medical model of chronic disease prevention—the concept that in the arena of noninfectious chronic disease, individuals play a major role in causing their own illnesses by such behaviors as smoking, drinking alcohol, and eating high-fat foods. The corollary to this view is that chronic disease mortality rates can be reduced by persuading individuals to change their lifestyles. These statements are true, but they do not tell the whole story.

An alternative ideology, which fits more closely with the public health approach to chronic disease prevention, argues that modern industrial society, rather than the individuals living in that society, creates the conditions leading to heart disease, cancer, stroke, and other major chronic diseases of the developed world. Tobacco advertising; processed high-fat, high-salt foods in “supersized” portions; easy availability of alcoholic beverages; societal stress; an urbanized and suburbanized existence that substitutes automobile travel for exercise; and a markedly unequal distribution of wealth are the substrates upon which the modern epidemic of chronic disease has flourished. Such a worldview leads to an emphasis on societal rather than individual strategies for chronic disease prevention (Fee and Krieger, 1993).

Both the medical and the public health models (seeing responsibility as both individual and societal) must be joined to further implement the second epidemio-logic revolution; medical caregivers must attempt to change high-risk lifestyles of their individual patients, and society must search for ways to reduce the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and rich foods. One model that bridges the medical and public health approaches is community-oriented primary care. In this model, primary care clinicians systematically define a target population, determine its health needs, and develop community-based interventions to address these needs (Nutting, 1990). The target population could be as simple as the patients enrolled in a primary care practice, or more ambitiously, an entire neighborhood. For example, a pediatrician might review data on her enrolled patients and find that many children are obese. In addition to counseling individual families in her practice, in the Community Oriented Primary Care model the pediatrician would also work with community members and agencies on broader public health interventions, such as advocating for improved school lunch programs and more time for physical education classes in the local schools, or encouraging the local health department to launch a media campaign promoting consumption of water instead of sweetened beverages.

To provide examples of different approaches to preventing illness, we have chosen to discuss two serious health problems in the United States: coronary heart disease and breast cancer.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is associated with four major risk factors: the eating of a rich diet (the principal cause of the CHD epidemic), elevated levels of serum cholesterol, cigarette smoking, and hypertension (Stamler, 1992a).

Primary prevention strategies are available for CHD because the causes of the disease are well understood. Primary CHD prevention involves risk factor reduction, including cessation of cigarette smoking, replacement of rich diets by low-fat diets, and control of hypertension. These strategies have been largely responsible for the large decrease in CHD death rates (Figure 11–1).

Figure 11–1. Trends in age-adjusted mortality from coronary heart disease in the United States, 1980–2006.

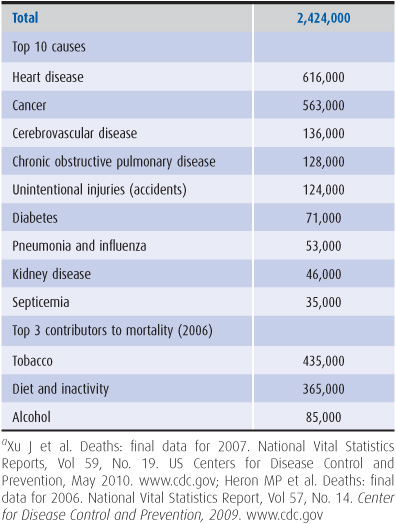

Tobacco has been called the smallpox virus of chronic disease—a harmful agent whose elimination from the planet would benefit humankind (Fee and Krieger, 1993). Since the 1964 release of the first Surgeon General’s Report on the Health Consequences of Smoking, the smoking behavior of the US population has changed dramatically. Between 1965 and 2007, the age-adjusted percentage of adult men who were current smokers dropped from 51% to 22%; for adult women, the decline was from 34% to 18% (Figure 11–2). These reductions in smoking prevalence avoided an estimated 3 million deaths between 1964 and 2000—a major public health achievement (Warner, 1989). However, rates of smoking are far higher among people with lower educational levels and smoking continues to be the leading cause of death in the United States (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

Figure 11–2. Cigarette smoking by persons 18 years and older in the United States in 1965 (light blue bars) and 2007 (dark blue bars). Percentages are age adjusted. (US Department of Health and Human Services. Health United States. 2009.)

Antismoking campaigns have been relatively successful for well-educated people, but less so for people with less education, who also tend to be poorer. Between 1974 and 2007, cigarette smoking declined 38% among the least educated persons, while it dropped 67% among the most educated. In 2006, 30% of the least educated persons smoked cigarettes, compared with only 9% of the most educated (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

Since the 1969 ban on radio and television cigarette advertising, the tobacco industry has increased its advertising expenditures dramatically in the print media and through sponsorship of community events. In 2005, tobacco advertising expenditures exceeded $13 billion, almost double the 1999 figure (Bayer et al, 2002; Cokkinides et al, 2009). Tobacco industry documents prove that the principal target group for cigarette advertising is young adults (Ling and Glantz, 2002). The antismoking campaign of the past 30 years has merged the medical and public health models of prevention. Physician counseling can influence smokers to quit. In 2006, however, only 34% of low-income smokers had smoking cessation discussions with their health care provider (Cokkinides et al, 2009) and relapse rates for those who quit after receiving active treatment are 77% at 12 months (Mannino, 2009). Public health measures are more effective, including public education, cigarette taxes, and restriction of smoking in public places. A 10% increase in the price of cigarettes reduces cigarette consumption by 3% to 5%. Yet compared with other developed nations, the United States has relatively low taxes on tobacco (Cokkinides et al, 2009; Schroeder and Warner, 2010).

A rich diet is a diet high in fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, salt, and often alcohol, and one with a high caloric intake in relation to the amount of energy expended (Stamler, 1992a). The rich diet produces CHD primarily by causing an increase in low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Lowering cholesterol levels has been shown to reduce the risk of heart attacks caused by CHD.

In the late 1980s, a major national campaign was launched by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to reduce serum cholesterol levels. This National Cholesterol Education Program is based on the medical model, with health care providers screening individuals for elevated cholesterol and aggressively treating hyperlipidemic patients with diet, cholesterol-lowering medications, or both (Grundy et al, 2004).

Public health analysts have criticized the NIH strategy as relying too heavily on a medical model of prevention that is expensive and of potentially limited effectiveness. The NIH approach targets more than 100 million people who need dietary changes and recommends drug treatment for many of these individuals.

The use of statin drugs to treat hyperlipidemia in people with known CHD (secondary prevention) and without CHD (primary prevention) has been shown to reduce deaths from CHD and deaths from all causes (Steinberg and Gotto, 1999). However, the effectiveness of drug treatment is far greater if it is used in secondary rather than primary prevention (Hayward et al, 2010). For primary prevention, 53 patients would have to take a statin drug for 5 years to prevent one patient from experiencing a fatal or nonfatal coronary event. For secondary prevention (patients with known CHD), statin drugs can prevent approximately one nonfatal myocardial infarction or death for every 10 patients treated, at a far lower cost for every year of life saved (Pharoah and Hollingworth, 1996; Lloyd-Jones, 2001).

The NIH cholesterol reduction strategy highlights the paradox of primary prevention: Prevention within a population of healthy individuals may be better (and less expensively) served by broad public health efforts to reduce risk among the majority of people at moderate risk than by concentrating intensive medical interventions on the smaller number of high-risk persons (Rose, 1985). The traditional orientation of physicians toward individual patients (the medical model) has led the medical profession and the NIH to emphasize identification and treatment of high-risk individuals with elevated cholesterol levels. Pharmaceutical manufacturers also have an interest in promoting a medical model of prevention that relies on prescribing medications. Reducing the mean cholesterol level of the US population rather than reducing the individual cholesterol counts of hyperlipidemic patients may have better long-term results for primary prevention.

Currently, public health efforts to curb the consumption of rich foods are failing; 74% of adults in the United States were classified as overweight or obese in 2008, compared with 46% in the early 1960s (Ogden and Carroll, 2010). The food industry spends billions of dollars on advertising, a substantial portion of which promotes high-fat fast foods. Proposals have been made to copy the strategy used by tobacco prevention campaigns in reducing the availability of high-fat foods; for example, taxing unhealthy foods, changing school lunch programs to reduce their fat content, restricting food advertising directed at children, and eliminating school-based candy and soft-drink vending machines are primary preventive measures that are gaining public acceptance (Frieden et al, 2010). Growing attention is also being paid to the billions of dollars annually in federal government subsidies to agribusinesses for growing corn, which has contributed to the flooding of the nation with low-cost, high fructose corn sweeteners and other high-calorie processed foods. Public health advocates have called for reforms to the federal farm bill to reduce subsidies for obesogenic foods and to provide more support for sustainable farming of healthful fruits and vegetables (Pollan, 2007; Wallinga, 2010).

Risk factors for hypertension include high salt intake, low potassium intake, high ratio of dietary sodium to potassium, obesity, and excess alcohol intake; other important risk factors likely exist. Prior to the advent of modern agriculture, intake of sodium was low and intake of potassium high, and high levels of physical exertion prevented persons from being overweight.

CHD risk is associated with increased blood pressure, even at relatively moderate levels of blood pressure elevation. Individuals with systolic blood pressures of 130 to 140 mm Hg have almost twice the cardiovascular risk of those with systolic blood pressures less than 110 mm Hg. One quarter of hypertension-related cardiovascular deaths take place among borderline hypertensives, and in the United States, 90% of men aged 35 to 57 years have blood pressure levels that create excess cardiovascular risk. Thus, it can be said that high blood pressure as a risk factor for CHD is a problem for the entire population and not simply a problem for the 20% to 25% of the population with frank hypertension. Similarly to the cholesterol situation, the greatest impact in reducing hypertension-related CHD mortality rates will come from a reduction in the blood pressure of the large number of borderline hypertensives rather than from focusing solely on people with very high blood pressure (Stamler, 1992b).

Primary prevention of high blood pressure can be accomplished by a reduction in the daily intake of salt by 3 g per person. Currently, the average man in the United States consumes 10.4 g of salt per day, with women eating 7.3 g. Such a change would reduce the number of new CHD cases by 60,000 per year. This public health approach would be as effective as the use of medical treatment to control the blood pressures of the 65 million people in the United States with hyper-tension (Bibbins-Domingo et al, 2010).

Prevention of hypertension has focused on screening and early treatment of elevated blood pressure. These measures are considered secondary prevention (early diagnosis and intervention) with respect to high blood pressure as a disease but are categorized as primary prevention (averting the occurrence) with respect to CHD. American medicine has a poor record in lowering elevated blood pressures; only 50% of hypertensives are adequately controlled (Egan et al, 2010)

Whereas mortality rates for cardiovascular disease declined since the late 1960s, cancer mortality rates continued to increase through 1990. Between 1990 and 2006, cancer mortality rates dropped by 16%, probably as a result of reductions in cigarette smoking. Breast cancer mortality rates have also decreased during those years, but are considerably higher for African American women than for white women (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

The designing of effective primary prevention for a disease generally depends on an understanding of the epidemiology of that disease. In the case of lung cancer, the discovery of the link with cigarette smoking allowed a widespread primary prevention program to be developed—the antismoking campaign. But the causes of many cancers are still unclear, meaning that preventive strategies must use secondary rather than primary prevention. Pap smears for early detection of cervical cancer, fecal occult blood testing and colonoscopy for early detection of colorectal cancer, and mammography for early detection of breast cancer are examples of secondary prevention.

Multiple risk factors for breast cancer have been uncovered, including age greater than 65 years, a family history of breast cancer, atypical hyperplasia on breast biopsy, birth in North America or northern Europe, and genetic susceptibility related to the BRCA geno-type. Women with more years of ovulatory menstrual cycles have a greater risk, indicating a hormonal influence on the disease (American Cancer Society, 2011).

However, only one-fourth of breast cancer cases can be accounted for by these risk factors. The differences between high and low age-adjusted breast cancer risk in the United States are small compared with the differences between such high-incidence nations as the United States and low-incidence (generally underdeveloped) nations. Perhaps unknown agents related to modern industrialization are the primary causes of breast cancer, while such influences as female hormones are secondary promoters of the disease.

The age-adjusted incidence (new cases) of breast cancer fell sharply in 2003 compared with 2002 and continued to fall slightly through 2006, a phenomenon temporally related to the drop in the use of hormone replacement therapy by women in the United States, occasioned by the widely publicized report from the Women’s Health Initiative providing new data on the risks of hormone replacement therapy (Ravdin et al, 2007). This association suggests that estrogen is an important cause or facilitator of breast cancer.

Evidence linking dietary fat to cancer of the breast is inconsistent and weak, and further research is needed on the role of environmental carcinogens (American Cancer Society, 2011). From the 1940s to the 1980s, industrial production of synthetic organic chemicals rose from 1 billion to 400 billion pounds annually, and the volume of hazardous wastes also increased 400-fold during that period (Epstein, 1990, 1994). One study estimated that toxic chemicals encountered at work-places are responsible for 20% of all human cancers (Landrigan, 1992). Estrogens have been used as additives to poultry and cattle feed, and pesticide residues contain estrogen-like compounds that may contribute to breast cancer causation (Davis and Bradlow, 1995). Some studies have linked breast cancer risk to organo-chlorine insecticides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and organic solvents, but research on these environmental causes of breast cancer has been inadequate and inconsistent (Brody and Rudel, 2003).

Lack of knowledge has forced modern medicine to retreat to secondary prevention (ie, early diagnosis through breast examinations and mammography) to reduce mortality rates in women with the disease. Thankfully, breast cancer, like cervical cancer, lends itself to secondary prevention techniques. Periodic mammograms can reduce breast cancer mortality rates in women aged above 50 years. Yet many breast cancer activists decry the relatively paltry sums going for basic epidemiologic research to determine the causes of breast cancer.

The examples of CHD and breast cancer illustrate different aspects of illness prevention. Primary prevention has been successful in reducing mortality rates for CHD. Both public health and medical approaches have been used, with far greater emphasis given to the latter strategy. Secondary prevention has had some success in reducing breast cancer mortality rates, but the incidence of the disease remains high and primary prevention is badly needed.

The influence of prevention on medical care costs is a complex one. As a rule, primary prevention using public health measures is far more cost-effective than primary prevention through medical care; public health measures do not require many millions of expensive one-to-one interactions with medical care providers.

In the arena of individual medical care prevention, some measures save money and some do not. Every dollar invested in measles, mumps, and rubella immunizations saves many more dollars in averted medical care costs. Physician counseling on smoking cessation is a low-cost activity that can reduce the multibillion dollar cost of caring for people with tobacco-related illness. These preventive care activities do reduce health care spending in the long run. In contrast, medical care to reduce cholesterol and high blood pressure are unlikely to result in significant savings to the health care system (Cohen et al, 2008).

Primary prevention through public health action can be enormously effective in reducing the burden of human suffering and the cost of treating disease. From 1900 to 1940, the nation’s public health efforts achieved a 97% reduction in the death rate for typhoid fever; 97% for diphtheria; 92% for infectious diarrhea; 91% for measles, scarlet fever, and whooping cough; and 77% for tuberculosis (Winslow, 1944). The imposition of a $2-per-pack increase in the tobacco tax could substantially reduce the $50-plus billion annual cost of tobacco-related disease, while at the same time yielding tens of billions of dollars per year in tax revenues—an ideal preventive measure that actually earns money. If the three primary preventive methods known to reduce the incidence of coronary heart disease, cancer, and stroke (ie, reduction in smoking, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure) were intensified, the medical care costs of these illnesses could be reduced by 50%. These three illnesses account for 20% of personal health care costs in the United States and reducing their incidence could yield a cost savings of billions of dollars per year. However, these savings are overstated because money saved by preventing disease X will ultimately be spent on the treatment of disease Y or Z, which will strike those people spared from disease X.

The goals of disease prevention are to delay disability and death and to maximize illness-free years of life. Improvements in living standards, public health measures, and preventive medical care have made enormous contributions toward the achievement of these goals. Producing further improvements in the overall health of society will likely depend on reducing the growing gap between the rich and the poor and shifting a greater proportion of the health dollar to disease prevention.

American Cancer Society. What are the risk factors for breast cancer, 2011. www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/detailedguide/breast-cancer-risk-factors. Accessed November 15, 2011.

Bayer R et al. Tobacco advertising in the United States. JAMA. 2002;287:2990.

Bibbins-Domingo K et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:590.

Brody JG, Rudel RA. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1007.

Brown EY, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI. Preventive health strategies and the policy makers? paradox. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:593.

Cohen JT et al. Does preventive care save money? N Engl J Med. 2008;358:661.

Cokkinides V et al. Tobacco control in the United States: recent progress and opportunities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:352.

Davis DL, Bradlow HL. Can environmental estrogens cause breast cancer? Sci Am. 1995;273:167.

Egan BM et al. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043.

Epstein SS. Losing the war against cancer: Who’s to blame and what to do about it. Int J Health Serv. 1990;20:53.

Epstein SS. Environmental and occupational pollutants are avoidable causes of breast cancer. Int J Health Serv. 1994;24:145.

Fee E, Krieger N. Thinking and rethinking AIDS: Implications for health policy. Int J Health Serv. 1993;23:323.

Frieden TR et al. Reducing childhood obesity through policy change. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:357.

Grundy SM et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227.

Hayward RA et al. Optimizing statin treatment for primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:69.

Heron MP et al. Deaths: Final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(14):1–134.

Keys A. Coronary heart disease in seven countries. Circulation. 1970;41(suppl 1):11.

Landrigan PJ. Commentary: Environmental disease: A preventable epidemic. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:941.

Ling PM, Glantz SA. Using tobacco industry marketing research to design more effective tobacco control campaigns. JAMA. 2002;287:2983.

Lloyd-Jones DM et al. Applicability of cholesterol-lowering primary prevention trials to a general population. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:949.

Loucks EB et al. Life-course socioeconomic position and incidence of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:829.

Mannino DM. Why won’t our patients stop smoking? Diabetes Care. 2009;32(suppl 2):S426.

McKeown T. Determinants of health. In: Lee PR, Estes CL, eds. The Nation’s Health. Boston, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 1990.

McKinlay JB et al. A review of the evidence concerning the impact of medical measures on recent mortality and morbidity in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19:181.

Nutting PA, ed. Community Oriented Primary Care: From Principle to Practice. Albuquerque, NM: University New Mexico Press; 1990.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1976–1980 through 2007–2008. June 2010. www.cdc.gov.

Pharoah PD, Hollingworth W. Cost effectiveness of lowering cholesterol concentration with statins in patients with and without pre-existing coronary heart disease. Br Med J. 1996;312:1443.

Pollan M. You are what you grow. N Y Times Mag. April 22, 2007.

Ravdin PM et al. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1670.

Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14:32.

Schroeder SA, Warner KE. Don’t forget tobacco. N Engl J Med. 2010;363;201.

Sigerist HE. Medicine and Human Welfare. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1941.

Stamler J. Established major coronary risk factors. In: Marmot M, Elliott P, eds. Coronary Heart Disease Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992a.

Stamler R. The primary prevention of hypertension and the population blood pressure problem. In: Marmot M, Elliott P, eds. Coronary Heart Disease Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992b.

Steinberg D, Gotto AM. Preventing coronary artery disease by lowering cholesterol levels. JAMA. 1999;282:2043.

Terris M. The changing relationships of epidemiology and society: The Robert Cruikshank Lecture. J Public Health Policy. 1985;6:15.

Terris M. What is health promotion? J Public Health Policy. 1986;7:147.

Terris M. Concepts of health promotion: Dualities in public health theory. J Public Health Policy. 1992a;13:267.

Terris M. Healthy lifestyles: The perspective of epidemiology. J Public Health Policy. 1992b;13:186.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Health United States. 2009. www.cdc.gov.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. 2010–2011. August 2010. www.ahrq.gov.

Wallinga D. Agricultural policy and childhood obesity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:405.

Warner KE. Smoking and health: A 25-year perspective. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:141.

Winslow CEA. Who killed Cock Robin? Am J Public Health. 1944;34:658.

Xu J et al. Deaths: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;59(19):1–135.