For 100 years, reformers in the United States have argued for the passage of a national health insurance program, a government guarantee that every person is insured for basic health care. Finally in 2010, the United States took a major step forward toward universal health insurance.

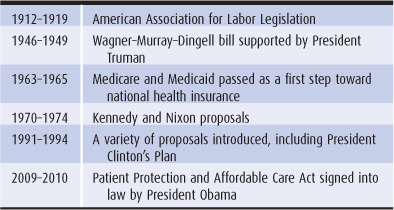

The subject of national health insurance has seen six periods of intense legislative activity, alternating with times of political inattention. From 1912 to 1916, 1946 to 1949, 1963 to 1965, 1970 to 1974, 1991 to 1994, and 2009 to 2010, it was the topic of major national debate. In 1916, 1949, 1974, and 1994, national health insurance was defeated and temporarily consigned to the nation’s back burner. Guaranteed health coverage for two groups—the elderly and some of the poor—was enacted in 1965 through Medicare and Medicaid. Expansion of coverage to over 30 million uninsured people was legislated with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. National health insurance means the guarantee of health insurance for all the nation’s residents—what is commonly referred to as “universal coverage.” Most of the focus, as well as the political contentiousness, of national health insurance proposals tends to concern how to finance universal coverage. Because health care financing is so interwoven with provider reimbursement and cost containment, national health insurance proposals usually also address those topics.

The controversies that erupt over universal health care coverage become simpler to understand if one returns to the four basic modes of health care financing outlined in Chapter 2: out-of-pocket payment, individual private insurance, employment-based private insurance, and government financing. There is general agreement that out-of-pocket payment does not work as a sole financing method for costly contemporary health care. National health insurance involves the replacement of out-of-pocket payments by one, or a mixture, of the other three financing modes.

Under government-financed national health insurance plans, funds are collected by a government or quasigovernmental fund, which in turn pays hospitals, physicians, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and other health care providers. Under private individual or employment-based national health insurance, funds are collected by private insurance companies, which then pay providers of care.

Historically, health care financing in the United States began with out-of-pocket payment and progressed through individual private insurance, then employment-based insurance, and finally government financing for Medicare and Medicaid (see Chapter 2). In the history of US national health insurance, the chronologic sequence is reversed. Early attempts at national health insurance legislation proposed government programs; private employment-based national health insurance was not seriously entertained until 1971, and individually purchased universal coverage was not suggested until the 1980s (Table 15–1). Following this historical progression, we shall first discuss government-financed national health insurance, followed by private employment-based and then individually purchased universal coverage. The most recent chapter of this history is the enactment under the administration of President Obama of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, a pluralistic approach to national health insurance that draws on all three of these financing models: government financing, employment-based private insurance, and individually purchased private insurance.

Table 15–1. Attempts to legislate national health insurance

In the early 1900s, 25% to 40% of people who became sick did not receive any medical care. In 1915, the American Association for Labor Legislation (AALL) published a national health insurance proposal to provide medical care, sick pay, and funeral expenses to lower-paid workers—those earning less than $1200 a year—and to their dependents. The program would be run by states rather than the federal government and would be financed by a payroll tax–like contribution from employers and employees, perhaps with an additional contribution from state governments. Payments would go to regional funds (not private insurance companies) under extensive government control. The funds would pay physicians and hospitals. Thus, the first national health insurance proposal in the United States—because the money was collected by quasi-public funds through a mandatory tax—can be considered a government-financed program (Starr, 1982).

In 1910, Edgar Peoples worked as a clerk for Standard Oil, earning $800 a year. He lived with his wife and three sons. Under the AALL proposal, Standard Oil and Mr. Peoples would each pay $13 per year into the regional health insurance fund, with the state government contributing $6. The total of $32 (4% of wages) would cover the Peoples family.

The AALL’s road to national health insurance followed the example of European nations, which often began their programs with lower-paid workers and gradually extended coverage to other groups in the population. Key to the financing of national health insurance was its compulsory nature; mandatory payments were to be made on behalf of every eligible person, ensuring sufficient funds to pay for people who fell sick.

The AALL proposal initially had the support of the American Medical Association (AMA) leadership. However, the AMA reversed its position and the conservative branch of labor, the American Federation of Labor, along with business interests, opposed the plan (Starr, 1982). The first attempt at national health insurance failed.

In 1943, Democratic Senators Robert Wagner of New York and James Murray of Montana, and Representative John Dingell of Michigan introduced a health insurance plan based on the social security system enacted in 1935. Employer and employee contributions to cover physician and hospital care would be paid to the federal social insurance trust fund, which would in turn pay health providers. The Wagner–Murray–Dingell bill had its lineage in the New Deal reforms enacted during the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. President Roosevelt had initially considered including a national health plan as part of the Social Security Act, but facing resistance from the AMA decided to omit health reform from the New Deal legislative package.

In the 1940s, Edgar Peoples’ daughter Elena worked in a General Motors plant manufacturing trucks to be used in World War II. Elena earned $3500 per year. Under the 1943 Wagner–Murray–Dingell bill, General Motors would pay 6% of her wages up to $3000 into the social insurance trust fund for retirement, disability, unemployment, and health insurance. An identical 6% would be taken out of Elena’s check for the same purpose. One-fourth of this total amount ($90) would be dedicated to the health insurance portion of social security. If Elena or her children became sick, the social insurance trust fund would reimburse their physician and hospital.

Edgar Peoples, in his seventies, would also receive health insurance under the Wagner–Murray–Dingell bill, because he was a social security beneficiary.

Elena’s younger brother Marvin was permanently disabled and unable to work. Under the Wagner–Murray–Dingell bill he would not have received government health insurance unless his state added unemployed people to the program.

As discussed in Chapter 2, government-financed health insurance can be divided into two categories. Under the social insurance model, only those who pay into the program, usually through social security contributions, are eligible for the program’s benefits. Under the public assistance (welfare) model, eligibility is based on a means test; those below a certain income may receive assistance. In the welfare model, those who benefit may not necessarily contribute, and those who contribute (usually through taxes) may not benefit (Bodenheimer and Grumbach, 1992). The Wagner–Murray–Dingell bill, like the AALL proposal, was a social insurance proposal. Working people and their dependents were eligible because they made social security contributions, and retired people receiving social security benefits were eligible because they paid into social security prior to their retirement. The permanently unemployed were not eligible.

In 1945, President Truman, embracing the general principles of the Wagner–Murray–Dingell legislation, became the first US president to strongly champion national health insurance. After Truman’s surprise election in 1948, the AMA succeeded in a massive campaign to defeat the Wagner–Murray–Dingell bill. In 1950, national health insurance returned to obscurity (Starr, 1982).

In the late 1950s, less than 15% of the elderly had health insurance (see Chapter 2) and a strong social movement clamored for the federal government to come up with a solution. The Medicare law of 1965 took the Wagner–Murray–Dingell approach to national health insurance, narrowing it to people 65 years and older. Medicare was financed through social security contributions, federal income taxes, and individual premiums. Congress also enacted the Medicaid program in 1965, a public assistance or “welfare” model of government insurance that covered a portion of the low-income population. Medicaid was paid for by federal and state taxes.

In 1966, at age 66, Elena Peoples was automatically enrolled in the federal government’s Medicare Part A hospital insurance plan, and she chose to sign up for the Medicare Part B physician insurance plan by paying a $3 monthly premium to the Social Security Administration. Elena’s son, Tom, and Tom’s employer helped to finance Medicare Part A; each paid 0.5% of wages (up to a wage level of $6600 per year) into a Medicare trust fund within the social security system. Elena’s Part B coverage was financed in part by federal income taxes and in part by Elena’s monthly premiums. In case of illness, Medicare would pay for most of Elena’s hospital and physician bills.

Elena’s disabled younger brother, Marvin, age 60, was too young to qualify for Medicare in 1966. Marvin instead became a recipient of Medicaid, the federal–state program for certain groups of low-income people. When Marvin required medical care, the state Medicaid program paid the hospital, physician, and pharmacy, and a substantial portion of the state’s costs were picked up by the federal government.

Medicare is a social insurance program, requiring individuals or families to have made social security contributions to gain eligibility to the plan. Medicaid, in contrast, is a public assistance program that does not require recipients to make contributions but instead is financed from general tax revenues. Because of the rapid increase in Medicare costs, the social security contribution has risen substantially. In 1966, Medicare took 1% of wages, up to a $6600 wage level (0.5% each from employer and employee); in 2004, the payments had risen to 2.9% of all wages. The Part B premium has jumped from $3 per month in 1966 to $115.40 per month in 2011.

Many people believed that Medicare and Medicaid were a first step toward universal health insurance. European nations started their national health insurance programs by covering a portion of the population and later extending coverage to more people. Medicare and Medicaid seemed to fit that tradition. Shortly after Medicare and Medicaid became law, the labor movement, Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, and Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan drafted legislation to cover the entire population through a national health insurance program. The 1970 Kennedy–Griffiths Health Security Act followed in the footsteps of the Wagner–Murray–Dingell bill, calling for a single federally operated health insurance system that would replace all public and private health insurance plans.

Under the Kennedy–Griffiths 1970 Health Security Program, Tom Peoples, who worked for Great Books, a small book publisher, would continue to see his family physician as before. Rather than receiving payment from Tom’s private insurance company, his physician would be paid by the federal government, perhaps through a regional intermediary. Tom’s employer would no longer make a social security contribution to Medicare (which would be folded into the Health Security Program) and would instead make a larger contribution of 3% of wages up to a wage level of $15,000 for each employee. Tom’s employee contribution was set at 1% up to a wage level of $15,000. These social insurance contributions would pay for approximately 60% of the program; federal income taxes would pay for the other 40%.

Tom’s Uncle Marvin, on Medicaid since 1966, would be included in the Health Security Program, as would all residents of the United States. Medicaid would be phased out as a separate public assistance program.

The Health Security Act went one step further than the AALL and Wagner–Murray–Dingell proposals: It combined the social insurance and public assistance approaches into one unified program. In part because of the staunch opposition of the AMA and the private insurance industry, the legislation went the way of its predecessors: political defeat.

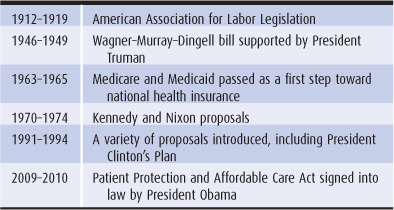

In 1989, Physicians for a National Health Program offered a new government-financed national health insurance proposal. The plan came to be known as the “single-payer” program, because it would establish a single government fund within each state to pay hospitals, physicians, and other health care providers, replacing the multipayer system of private insurance companies (Himmelstein and Woolhandler, 1989). Several versions of the single-payer plan were introduced into Congress in the 1990s, each bringing the entire population together into one health care financing system, merging the social insurance and public assistance approaches (Table 15–2). The California Legislature, with the backing of the California Nurses Association, passed a single-payer plan in 2006 and 2008, but the proposals were vetoed by the Governor.

Table 15–2. Categories of national health insurance plans

In response to Democratic Senator Kennedy’s introduction of the 1970 Health Security Act, President Nixon, a Republican, countered with a plan of his own, the nation’s first employment-based, privately administered national health insurance proposal. For 3 years, the Nixon and Kennedy approaches competed in the congressional battleground; however, because most of the population was covered under private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid, there was relatively little public pressure on Congress. In 1974, the momentum for national health insurance collapsed, not to be seriously revived until the 1990s. The essence of the Nixon proposal was the employer mandate, under which the federal government requires (or mandates) employers to purchase private health insurance for their employees.

Tom Peoples’ cousin Blanche was a receptionist in a physician’s office in 1971. The physician did not provide health insurance to his employees. Under Nixon’s 1971 plan, Blanche’s employer would be required to pay 75% of the private health insurance premium for his employees; the employees would pay the other 25%.

Blanche’s boyfriend, Al, had been laid off from his job in 1970 and was receiving unemployment benefits. He had no health insurance. Under Nixon’s proposal, the federal government would pay a portion of Al’s health insurance premium.

No longer was national health insurance equated with government financing. Employer mandate plans preserve and enlarge the role of the private health insurance industry rather than replacing it with tax-financed government-administered plans. While the Nixon plan preserved existing government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, it proposed to expand coverage for the uninsured through a widening role for private, employment-based insurance. Government’s new role under the Nixon plan would be to enforce private health insurance as a required benefit for employed people. The Nixon proposal changed the entire political landscape of national health insurance, moving it toward the private sector. In later years, Senator Kennedy embraced the employer mandate approach himself, fearing that the opposition of the insurance industry and organized medicine would kill any attempt to legislate government-financed national health insurance.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the number of people in the United States without any health insurance rose from 25 million to more than 40 million (see Chapter 3). Approximately three-quarters of the uninsured were employed or were dependents of employed persons. The rapidly rising cost of health insurance premiums made insurance unaffordable for many businesses. In response to this crisis in health care access, President Clinton submitted legislation to Congress in 1993 calling for universal health insurance through an employer mandate, as well as broadened eligibility for Medicaid. Like the Nixon proposal, the essence of the Clinton plan was the requirement that employers pay for most of their employees’ private insurance premiums.

A variation on the employer mandate type of national health insurance is the voluntary approach. Rather than requiring employers to purchase health insurance for employees, employers are given incentives such as tax credits to cover employees voluntarily. The attempt of some states to implement this type of voluntary approach has failed to significantly reduce the numbers of uninsured workers.

In 1989, a new species of national health insurance appeared, sponsored by the conservative Heritage Foundation: the individual mandate. Just as many states require motor vehicle drivers to purchase automobile insurance, the Heritage plan called for the federal government to require all US residents to purchase individual health insurance policies. Tax credits would be made available on a sliding scale to individuals and families too poor to afford health insurance premiums (Butler, 1991). Under the most ambitious versions of universal individual insurance proposals, neither employer-sponsored group insurance nor government-administered insurance would continue to play a role in financing health care. These existing financing models would be dismantled and replaced by a universal, individual mandate program. Ironically, the individual insurance mandate shares at least one feature with the single-payer, government-financed approach to universal coverage: Both would severe the connection between employment and health insurance, allowing portability and continuity of coverage as workers moved from one employer to another or became self-employed.

Tom Peoples received health insurance through his employer, Great Books. Under an individual mandate plan, Tom would be legally required to purchase health insurance for his family. Great Books could offer a health plan to Tom and his coworkers but would not be required to contribute anything to the premium. If Tom purchased private health insurance for his family at a cost of $8000 per year, he would receive a tax credit of $4000 (ie, he would pay $4000 less in income taxes). Tom’s Uncle Marvin, formerly on Medicaid, would be given a voucher to purchase a private health insurance policy.

With individual mandate health insurance, the tax credits may vary widely in their amount depending on characteristics such as household income and how much of a subsidy the architects of individual mandate proposals build into the plan. In a generous case, a family might receive a $10,000 tax credit, subsidizing much of its health insurance premium. If the family’s tax liability is less than the value of the tax credit, the government would pay the family the difference between the family’s tax liability and $10,000.

A related version of the individual mandate is a voucher system. Instead of issuing tax credits, the federal government would issue a voucher for a fixed dollar amount that could be used toward the purchase of health insurance, just as some local government jurisdictions issue vouchers that may be used to enroll children in private schools. In the most sweeping proposals, a tax-financed voucher system would completely replace existing insurance programs directly administered by government as well as employer-sponsorship of private insurance (Emanuel and Fuchs, 2005). Another version of individual health insurance expansion is the voluntary concept, which was proposed by President George W. Bush. Uninsured individuals would not be required to purchase individual insurance but would receive a tax credit if they chose to purchase insurance. The level of the tax credits in the Bush plan and similar proposals have been small compared to the cost of most health insurance policies, with the result that these voluntary approaches if enacted would have induced very few uninsured people to purchase coverage.

Nearly 20 years after the Heritage Foundation drafted a proposal for a national individual mandate, Massachusetts enacted a state-level universal health coverage bill implementing the nation’s first legislated individual mandate. The Massachusetts plan, enacted under the leadership of Republican Governor Mitt Romney, mandates that every state resident must have health insurance coverage meeting a minimum standard set by the state. Individuals are required to provide proof of coverage at the time of filing their annual tax return, and face a financial penalty for failing to provide evidence of coverage. The state provides subsidies for purchase of private health insurance coverage to individuals with incomes below 300% of the federal poverty level if they are not covered by the state’s Medicaid program or through employment-based insurance.

Brian Mayflower earns $16,000 a year as a waiter to support himself as an aspiring actor in Boston. He has chronic asthma, with his inhaler medications alone costing more than $1,000 annually. He is not eligible for Medicaid and is required under the Massachusetts Plan to purchase a private health plan. As a low-income person, Brian receives a state subsidy for most of the premium cost of the plan. The plan has a $500 per year deductible but pays for most of Brian’s medications once he meets the annual deductible.

Brian’s sister Dorothy Mayflower is a self-employed accountant living in Springfield and earning $58,000 a year. At her income level, the Massachusetts state subsidy for insurance coverage would leave her having to pay $3000 per year toward the premium for a plan that has a $2000 per year deductible. Dorothy is in good health and is having trouble paying the mortgage on her house, which recently ballooned. She decides she will not enroll in a health insurance plan and instead pays the $900 fine to the state for not complying with the individual mandate.

Like the Nixon employer mandate proposal, the Massachusetts individual mandate does not eliminate existing government insurance programs; it extends the reach of private insurance through a government mandate, in this case for individually purchased private insurance. State government provides an income-adjusted subsidy for individual coverage for people not eligible for employer-sponsored insurance and limits the degree to which private plans can experience-rate their premiums. The Massachusetts plan allows insurers to offer policies with large amounts of cost-sharing in the form of high deductibles and coinsurance. The plan also includes a weak employer mandate, requiring employers with more than 10 employees to either contribute toward insurance coverage for their employees or pay into the state fund that underwrites public subsidies for the individual mandate and related programs.

The Massachusetts Health Plan of 2006 is credited with reducing the uninsurance rate among nonelderly adults in Massachusetts from 13% in 2006 to 5% in 2009 (Long and Stockley, 2010). Some residents of the state, such as Dorothy Mayflower, continue to have trouble affording private insurance even with some degree of state subsidy, and the high levels of cost-sharing allowed under the minimum benefit standards leave many insured individuals with substantial out-of-pocket payments. In 2008, 18% of low-income people in Massachusetts reported unmet health care needs due to costs (copayments, deductibles, uncovered services) and about 20% of the entire population experienced difficulty accessing primary care due to the primary care shortage (Clark et al, 2011).

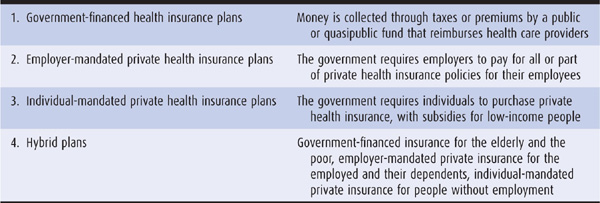

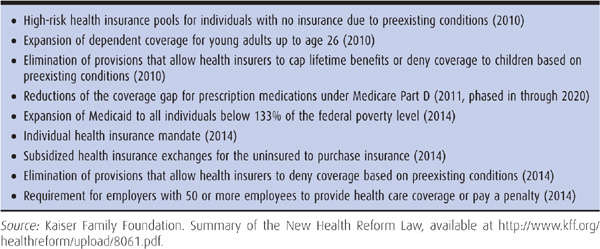

Following a year-long bitter debate, the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives and Senate passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) without a single Republican vote. President Obama, on March 23, 2010, signed the most significant health legislation since Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 (Morone, 2010). Although the ACA was attacked as “socialized medicine” and a “government takeover of health care,” its policy pedigree derives much more from the proposals of a Republican President (Nixon) and Republican Governor (Romney) than from the single-payer national health insurance tradition of Democratic Presidents Roosevelt and Truman. The pluralistic financing model of the ACA includes individual and employer mandates for private insurance and an expansion of the publicly financed Medicaid program. Ironically, despite the ACA’s close resemblance to the Massachusetts Health Plan of 2006, Mitt Romney, the former Governor of Massachusetts who supported and signed that state’s reform bill, upon turning his sights to his candidacy for the Republican nomination for the 2012 presidential election, called for repeal of the ACA.

In 2013, Mandy Must is uninsured and works for a small shipping company in Texas that does not offer health insurance benefits. In 2014, if the ACA survives legal and political challenges, she would be required to obtain private insurance coverage. Mandy earns about $35,000 per year, and in 2014 would receive a federal subsidy of about $2000 toward her purchase of an individual insurance policy with a premium cost of $5000.

In 2013, Walter Groop works full-time as a salesperson for a large department store in Miami which does not offer health insurance benefits to its workers. In 2014, he begins to apply for an individual policy to meet the requirements of the ACA, but his employer informs him that the department store would start contributing toward group health insurance coverage for its employees to avoid paying penalties under the ACA.

In 2013, Job Knaught has been an unemployed construction worker in St. Louis for over 18 months and, aside from an occasional odd job, has no regular source of income. Because he is not disabled, he does not qualify for Medicaid despite being poor. In 2014, Job becomes eligible for Missouri’s Medicaid program.

The ACA has four main components to its reform of health care financing:

1. Individual mandate: Beginning in 2014, the ACA requires virtually all US citizens and legal residents to have insurance coverage meeting a federally determined “essential benefits” standard. This standard would allow high-deductible plans to qualify, with out-of-pocket cost-sharing capped at $5950 per individual and $11,900 per family, in 2010 dollars. Those who fail to purchase insurance and do not qualify for public programs such as Medicaid, Medicare, or veteran’s health care benefits must pay a tax penalty which would be gradually phased in by 2016, when it would equal the greater of $695 per year for an individual (up to $2085 for a family) or 2.5% of household income. Individuals and families below 400% of the Federal Policy Level are eligible for income-based sliding-scale federal subsidies to help them purchase the required health insurance.

2. Employer mandate: Also beginning in 2014, employers with 50 or more full-time employees face a financial penalty if their employees are not enrolled in an employer-sponsored health plan meeting the essential benefit standard and any of their employees apply for federal subsidies for individually purchased insurance. While this measure does not technically mandate large employers to provide health benefits to their full-time workers, it functionally has this effect by penalizing employers who do not provide insurance benefits and leave their employees to fend for themselves to comply with the individual mandate.

3. Medicaid eligibility expansion: As discussed in Chapter 2, Medicaid eligibility has traditionally required both a low income and a “categorical” eligibility requirement, such as being a child or an adult with a permanent disability. Effective in 2014, the ACA eliminates the categorical eligibility requirement and requires that states make all US citizens and legal residents below 133% of the Federal Poverty Level eligible for their Medicaid programs. In 2011, 133% of the Federal Poverty Level was $14,484 for a single person and $29,726 for a family of 4. The federal government pays states 100% of the Medicaid costs for beneficiaries qualifying under the expanded eligibility criteria for 2014 through 2016, with states contributing 10% after 2016. The benefit package is similar to current Medicaid benefits.

4. Insurance market regulation: The ACA also imposes some new rules on private insurance. One of the first measures of the ACA to be implemented in 2010 was a requirement that private health plans allow young adults up to age 26 to remain covered as dependents under their parents’ health insurance policies. The ACA also eliminates caps on total insurance benefits payouts, prohibits denial of coverage based on preexisting conditions, and limits the extent of experience rating to a maximum ratio of 3-to-1 between a plan’s highest and lowest premium charge for the same benefit package. The ACA also establishes state-based insurance exchanges to function as a clearing house to assist people seeking coverage under the individual mandate to shop for insurance plans meeting the federal standards (Kingsdale and Bertko, 2010). The benefit packages offered by plans in the exchanges would vary depending on whether individuals purchase a low-premium bronze plan with high out-of-pocket costs, a high-premium platinum plan with low out-of-pocket costs, or the intermediate silver or gold plans. These regulatory measures were deemed by many to be essential to the feasibility and fairness of an individual mandate. For example, mandates cannot work if insurers may deny coverage to individuals with preexisting conditions or steeply experience rate premiums. The insurance industry, for its part, balks at these types of market reforms in the absence of a mandate, fearing adverse disproportionate enrollment of high-risk individuals when coverage is voluntary.

The major coverage provisions of the ACA and their timeline for implementation are summarized in Table 15–3.

Table 15–3. Key coverage measures and implementation timeline for the Affordable Care Act of 2010

If the ACA is implemented in its entirety, 32 million of the 51 million uninsured Americans are expected to receive insurance coverage, an estimated 16 million through Medicaid expansion and 16 million through the individual mandate (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). None of the coverage expansion measures would benefit undocumented immigrants; they would not be eligible for federal premium subsidies under the individual mandate nor for Medicaid except for emergency care.

The ACA is expected to cost $938 billion over 10 years, with most of the costs associated with Medicaid expansion and individual mandate subsidies. The law is financed by a combination of new taxes and fees and by cost savings in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Individuals with earnings over $200,000 and married couples with earnings over $250,000 would pay more for Medicare Part A. Health insurance companies, pharmaceutical firms, and medical device manufacturers would pay yearly fees. Medicare Advantage insurance plans and hospitals would receive less payment from the Medicare program. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the new law would reduce the federal deficit by $124 billion over 10 years, though the CBO projection is not universally accepted.

In developing a proposal to expand coverage by building on the existing pluralistic funding model rather than turning to a single-payer model, President Obama and his congressional allies successfully calculated that they would be able to garner the political support of some powerful interest groups, such as the American Medical Association and pharmaceutical industry, that had been stalwart opponents of health reform proposals in prior eras (Morone, 2010). However, some conservative groups that opposed the ACA did not relent after the Act’s passage, and the ACA has come under political and judicial threats since its enactment. One of the first acts passed by the House of Representatives in its 2011 session after Republicans regained a majority of seats in the House was repeal of the ACA. The ACA remained law because the Senate, with a Democratic majority, did not vote to repeal. Republican Governors and Attorney Generals in many states filed suits against the ACA, challenging the constitutionality of the federal government’s mandating of individuals to purchase a private product. Federal judges in district courts have issued different rulings on the constitutionality of the ACA, and the case will ultimately be heard by the US Supreme Court.

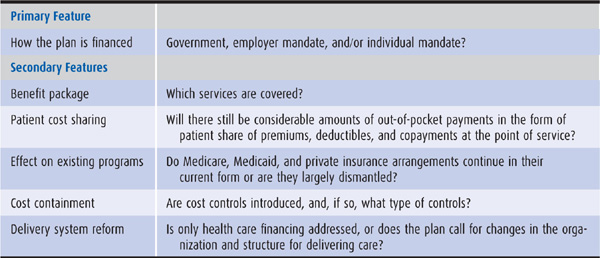

The primary distinction among national health insurance approaches is the mode of financing: government versus employment-based versus individual-based health insurance, or a mixture of all three. But while the overall financing approach may be considered the headline news of reform proposals, some of the details in the fine print are extremely important in determining whether a universal coverage plan will be able to deliver true health security to the public (Table 15–4). What are some of these secondary features?

Table 15–4. Features of national health insurance plans

An important feature of any health plan is its benefit package. Most national health insurance proposals cover hospital care, physician visits, laboratory, x-rays, physical and occupational therapy, inpatient pharmacy, and other services usually emphasizing acute care. One important benefit not included in the original Medicare program was coverage of outpatient medications. This coverage was later added in 2003 under Medicare Part D. Mental health services have often not been fully integrated into the benefit package of universal coverage proposals, a situation that has in part been addressed by the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 and Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 which apply to group private health insurance plans. Neither the ACA nor most of its reform proposal precursors have included comprehensive benefits for dental care, long-term care, or complementary medicine services such as acupuncture.

Patient cost sharing involves payments made by patients at the time of receiving medical care services. It is sometimes broadened to include the amount of health insurance premium paid directly by an individual. Naturally, the breadth of the benefit package influences the amount of patient cost sharing: The more the services are not covered, the more the patients must pay out of pocket. Many plans impose patient cost sharing requirements on covered services, usually in the form of deductibles (a lump sum each year), coin-surance payments (a percentage of the cost of the service), or copayments (a fixed fee, eg, $10 per visit or per prescription). In general, single payer proposals restrict cost sharing to minimal levels, financing most benefits from taxes. In comparison, the individual mandate provisions of the Massachusetts Health Act and the ACA include considerable amounts of cost sharing. The ACA, for example, would require an individual such as Mandy Must with an income between 300% and 400% of the federal poverty level to pay up to 9.5% of her income toward a health insurance premium, in addition to having to potentially pay thousands of dollars per year in deductibles and copayments at the time of service. Critics have argued that this degree of out-of-pocket payment raises questions about whether the Affordable Care Act is a bit of a misnomer and that people of modest incomes will continue to be underinsured and subject to large amounts of out-of-pocket expenses. The arguments for and against cost sharing as a cost containment tool are discussed in Chapter 9.

Any national health insurance program must interact with existing health care programs, whether Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance plans. Single-payer proposals make among the most far-reaching changes: Medicaid and private insurance are eliminated in their current form and are melded into a single insurance program that resembles a Medicare-type program for all Americans. The most sweeping versions of individual mandate plans, such as that proposed by the Heritage Foundation, would dismantle both employment-based private insurance and government-administered insurance programs. Employer mandates, which extend rather than supplant employment-based coverage, tend to have the least effect on existing dollar flow in the health care system, as do pluralistic models such as the ACA that preserve and extend existing financing models through mandates for private insurance and broadened eligibility for Medicaid.

By increasing people’s access to medical care, national health insurance has the capacity to cause a rapid increase in national health expenditures, as did Medicare and Medicaid (see Chapter 2). By the 1990s, policymakers recognized that an increase in access must be balanced with measures to control costs.

Different national health insurance proposals have vastly disparate methods of containing costs. As noted above, individual- and employment-based proposals tend to use patient cost sharing as their chief cost control mechanism. In contrast, government-financed plans look more to global budgeting and regulation of fees to keep expenditures down. Single-payer plans, which concentrate health care funds in a single public insurer, can more easily establish a global budgeting approach than can plans with multiple private insurers.

Proposals that build on the existing pluralistic financing model of US health care, such as the Clinton health plan and the ACA, face challenges in taming the unrelenting increases in national health care expenditures that seem to be endemic to a fragmented financing system. One of the items that contributed to the demise of President Clinton’s health reform proposal before it could even be formally introduced as a bill in Congress was the inclusion of a measure to allow the federal government to cap the annual rates of increases in private health insurance premiums. President Obama eschewed such a regulatory approach in developing the ACA, and the ACA includes much weaker language about private insurance plans needing to “justify” premium increases to be able to continue to participate in state health insurance exchanges. In an effort to control costs, the ACA limits the percentage of health insurance premiums that can be retained by an insurance company in the form of overhead and profits (a concept known as the “medical loss ratio,” whereby a greater loss ratio means more premium dollars being “lost” by the company in the form of payments for actual health care services). The ACA also caps the amount that an employer can contribute toward a health insurance premium as a nontaxable benefit to the employee ($10,200 for an individual policy and $27,500 for a family policy), in an attempt to discourage enrollment in the most expensive plans. Many of the savings in the ACA are expected to come from slowing the rate of growth in expenditures for Medicare through measures such as reducing payments to Medicare Advantage HMO plans and appointing an Independent Payment Advisory Board to recommend methods to contain Medicare costs. Yet another strategy of the ACA for addressing costs is to redesign health care delivery to achieve better value, discussed next.

Throughout the history of national health insurance proposals in the United States, reformers viewed their primary goal as modifying the methods of financing health care to achieve universal coverage. Addressing how providers were paid often emerged as a closely related consideration because of its importance for making universal coverage affordable. However, intervening in the way in which health care was organized and delivered was typically not something that featured prominently in reform proposals. Reformers tended to have their work cut out to overcome the strong opposition of the AMA and hospital associations to health insurance reform without further antagonizing those interests by challenging professional sovereignty over health care organization and delivery. Even many advocates of single payer reform in the United States looked to the lessons of the introduction of government insurance programs in the Canadian provinces, where until recently government took great pains to largely focus on insurance financing and payment rate regulation and not on reforming models for care delivery.

The ACA went considerably farther than most previous major reform proposals in the United States in including measures to shape health care delivery. The ACA created an Innovation Center in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to spearhead efforts to redesign care models in the United States. One of the charges to the Innovation Center is to promote Accountable Care Organizations. As discussed in Chapter 6, Accountable Care Organizations are intended to be provider-organized systems for delivering care that can emphasize more integrated and coordinated models of care for defined populations of patients, with financial incentives to reward higher value care. The Innovation Center also has responsibility for encouraging development of primary care Patient-Centered Medical Homes, also discussed in Chapter 5. Other measures in the ACA call for pilot programs to expand the roles of nurses, pharmacists, and other health care professionals in redesigned care models.

Historically, in the United States the government-financed single payer road to national health insurance is the oldest and most traveled of the three approaches. Advocates of government financing cite its universality: Everyone is insured in the same plan simply by virtue of being a US resident. Its simplicity creates a potential cost saving: The 25% of health expenditures spent on administration could be reduced, thus making available funds to extend health insurance to the uninsured. Employers would be relieved of the burden of providing health insurance to their employees. Employees would regain free choice of physician, choice that is being lost as employers are choosing which health plans (and therefore which physicians) are available to their workforce. Health insurance would be delinked from jobs, so that people changing jobs or losing a job would not be forced to change or lose their health coverage. Single-payer advocates, citing the experience of other nations, argue that cost control works only when all health care moneys are channeled through a single mechanism with the capacity to set budgets (Himmelstein and Woolhandler, 1989). While opponents accuse the government-financed approach as an invitation to bureaucracy, single-payer advocates point out that private insurers have average administrative costs of 14%, far higher than government programs such as Medicare with its 2% administrative overhead. A cost-control advantage intrinsic to tax-financed systems in which a public agency serves as the single payer for health care is the administrative efficiency of collecting and dispensing revenues under this arrangement.

Single-payer detractors charge that one single government payer would have too much power over people’s health choices, dictating to physicians and patients which treatments they can receive and which they cannot, resulting in waiting lines and the rationing of care. Opponents also state that the shift in health care financing from private payments (out of pocket, individual insurance, and employment-based insurance) to taxes would be unacceptable in an antitax society. Moreover, the United States has a long history of politicians and government agencies being overly influenced by wealthy private interests, and this has contributed to making the public mistrustful of the government.

The employer mandate approach—requiring all employers to pay for the health insurance of their employees—is seen by its supporters as the most logical way to raise enough funds to insure the uninsured without massive tax increases (though employer mandates have been called hidden taxes). Because most people younger than 65 years now receive their health insurance through the workplace, it may be less disruptive to extend this process rather than change it.

The conservative advocates of individual-based insurance and the liberal supporters of single-payer plans both criticize employer mandate plans, saying that forcing small businesses—many of whom do not insure their employees—to shoulder the fiscal burden of insuring the uninsured is inequitable and economically disastrous; rather than purchasing health insurance for their employees, many small businesses may simply lay off workers, thereby pitting health insurance against jobs. Moreover, because millions of people change their jobs in a given year, job-linked health insurance is administratively cumbersome and insecure for employees, whose health security is tied to their job. Finally, critics point out that under the employer mandate approach, “Your boss, not your family, chooses your physician”; changes in the health plans offered by employers often force employees and their families to change physicians, who may not belong to the health plans being offered.

Advocates of the individual mandate assert that their approach, if adopted as the primary means of financing coverage, would free employers of the obligation to provide health insurance, and would grant individuals a stable source of health insurance whether they are employed, change jobs, or become disabled. There would be no need either to burden small businesses with new expenses and thereby disrupt job growth or to raise taxes substantially. While opponents argue that low-income families would be unable to afford the mandatory purchase of health insurance, supporters claim that income-related tax credits are a fair and effective method to assist such families (Butler, 1991).

The individual mandate approach is criticized as inefficient, with each family having to purchase its own health insurance. To enforce a requirement that every person buy coverage could be even more difficult for health insurance than for automobile insurance. Moreover, to reduce the price of their premiums, many families would purchase “bare-bones insurance” plans with low-cost, high-deductible coverage and a scanty benefit package, thereby leaving lower- and middle-income families with potentially unaffordable out-of-pocket costs.

The concept of national health insurance rests on the belief that everyone should contribute to finance health care and everyone should benefit. People who pay more than they benefit are likely to benefit more than they pay years down the road when they face an expensive health problem. In 2009, national health insurance took center stage in the United States with the fierce debate over health reform legislation that resulted in the ACA. This debate revealed a wide gulf between those who believe that all people should have financial access to health care and those who do not. The fate of the ACA will determine which of those two beliefs holds sway in the United States, until now the only developed nation that does not insure virtually all its citizens for health care.

Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Financing universal health insurance: Taxes, premiums, and the lessons of social insurance. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1992;17:439.

Butler SM. A tax reform strategy to deal with the uninsured. JAMA. 1991;265:2541.

Clark CR et al. Lack of access due to costs remains a problem for some in Massachusetts despite the state’s health reforms. Health Aff. 2011;30:247.

Emanuel EJ, Fuchs VR. Health care vouchers—a proposal for universal coverage. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1255.

Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Writing Committee of Physicians for a National Health Program: A national health program for the United States: A physicians’ proposal. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:102.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Summary of New Health Reform Law, 2010. http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/8061.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2011.

Kingsdale J, Bertko J. Insurance exchanges under health reform: Six design issues for the states. Health Aff. 2010;29:1158.

Long SK, Stockley K. Sustaining health reform in a recession: An update on Massachusetts as of Fall 2009. Health Aff. 2010;29:1234.

Morone J. Presidents and health reform: From Franklin D. Roosevelt to Barack Obama. Health Aff. 2010;29:1096.

Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books; 1982.