As this book enters its closing chapters, it is worth stepping back from the detailed workings of the US health care system to view the system as a larger whole. Who are the major actors? How have they interacted over the past few decades? What might the future bring?

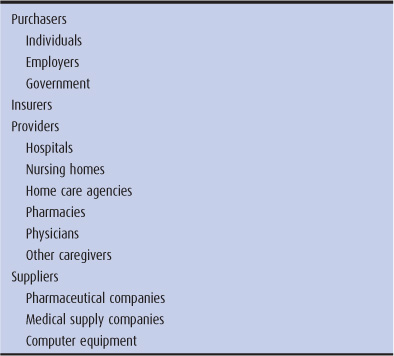

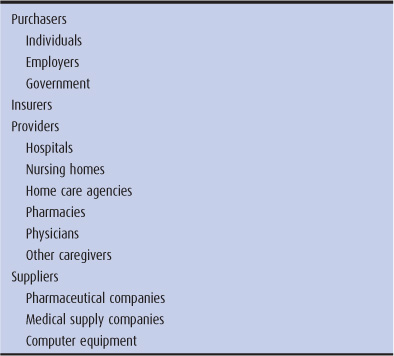

The health care sector of the nation’s economy is a 2.5 trillion dollar-plus system that finances, organizes, and provides health care services for the people of the United States. Four major actors can be found on this stage (Table 16–1).

Table 16–1. The four major actors

1. The purchasers supply the funds. These include individual health care consumers, businesses that pay for the health insurance of their employees, and the government, which pays for care through public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. All purchasers of health care are ultimately individuals, because individuals finance businesses by purchasing their products and fund the government by paying taxes. Nonetheless, businesses and the government assume special importance as the nation’s organized purchasers of health care.

2. The insurers receive money from the purchasers and reimburse the providers. Traditional insurers take money from purchasers (individuals or businesses), assume risk, and pay providers when policyholders require medical care. Yet some insurers are the same as purchasers; the government can be viewed as an insurer or purchaser in the Medicare and Medicaid programs, and businesses that self-insure their employees can similarly occupy both roles. (In previous chapters, we have used the term “payer” to refer to both purchasers and insurers.)

3. The providers, including hospitals, physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, social workers, nursing homes, home care agencies, and pharmacies, actually provide the care. While health maintenance organizations (HMOs) are generally insurers, some are also providers, owning hospitals and employing physicians.

4. The suppliers are the pharmaceutical, medical supply, and computer industries, which manufacture equipment, supplies, and medications used by providers to treat patients.

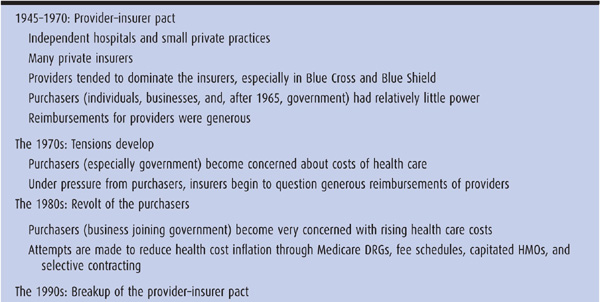

Insurers, providers, and suppliers make up the health care industry. Each dollar spent on health care represents an expense to the purchasers and a gain to the health care industry. In the past, purchasers viewed this expense as an investment, money spent to improve the health of the population and thereby the economic and social vitality of the nation. But over the past 35 years, a fundamental conflict has intensified between the purchasers and the health care industry: The purchasers wish to reduce, and the health care industry to increase, the number of dollars spent on health care. We will now explore the changing relationships among purchasers, insurers, providers, and suppliers.

During this period, independent hospitals and small private physician offices populated the US health delivery system (see Chapter 6). Some large institutions existed that combined hospital and physician care (eg, the Kaiser–Permanente system, the Mayo Clinic, and urban medical school complexes), but these were the exception (Starr, 1982). Competition among health care providers was minimal because most geographic areas did not have an excess of facilities and personnel. The health care financing system included hundreds of private insurance companies, joined by the governmental Medicare and Medicaid programs enacted in 1965. The United States had a relatively dispersed health care industry.

Bert Neighbor was a 63-year-old man who developed abdominal pain in 1962. Because he was well insured under Blue Cross, his physician placed him in Metropolitan Hospital for diagnostic studies. On the sixth hospital day, a colon cancer was surgically removed. On the fifteenth day, Mr. Neighbor went home. The hospital sent its $1200 bill to Blue Cross, which paid the hospital for its total costs in caring for Mr. Neighbor. In calculating Mr. Neighbor’s bill, Metropolitan Hospital included a small part of the cost of the 80-bed new building under construction.

At a subsequent meeting of the Blue Cross board of directors, the hospital administrator (also a Blue Cross director) was asked whether it was reasonable to include the cost of capital improvements when preparing a bill. Other Blue Cross directors, also hospital administrators with construction plans, argued that it was proper, and the matter was dropped. In the same meeting, the directors voted a 34% increase in Blue Cross premiums. Sixteen years later, a study revealed that the metropolitan area had 300 excess hospital beds, with hospital occupancy down from 82% to 60% over the past decade.

A defining characteristic of the health care industry was an alliance of insurers and providers. This provider–insurer pact was cemented with the creation of Blue Cross and Blue Shield, the nation’s largest health insurance system for half a century (see Chapter 2). Blue Cross was formed by the American Hospital Association, and Blue Shield was run by state medical societies affiliated with the American Medical Association. In the case of the Blues, the provider–insurer relationship was more than a political alliance; it involved legal control of insurers by providers. As in the example of Metropolitan Hospital, the providers set generous rules of reimbursement, and the Blues made the payments without asking too many questions (Law, 1974). Commercial insurers usually played by the reimbursement rules already formulated by the physicians, hospitals, and Blues, paying for medical services without asking providers to justify their prices or the reasons for the services.

By the 1960s, the power of the provider–insurer pact was so great that the hospitals and Blue Cross virtually wrote the reimbursement provisions of Medicare and Medicaid, guaranteeing that physicians and hospitals would be paid with the same bountiful formulas used for private patients (Law, 1974). With open-ended reimbursement policies, the costs of health care inflated at a rapid pace.

The disinterest of the chief organized purchaser (business) stemmed from two sources: the healthy economy and the tax subsidy for health insurance. From 1945 through 1970, US business controlled domestic and foreign markets with little foreign competition. Labor unions in certain industries had gained generous wages and fringe benefits, and business could afford these costs because profits were high and world economic growth was robust (Kuttner, 1980; Kennedy, 1987). The cost of health insurance for employees was a tiny fraction of total business expenses. Moreover, payments by business for employee health insurance were considered a tax-deductible business expense, thereby cushioning any economic drain on business (Reinhardt, 1993). For these reasons, increasing costs generated by providers and reimbursed by insurers were passed on to business, which with few complaints paid higher and higher premiums for employees’ health insurance, and thereby underwrote the expanding health care system. No countervailing forces “put the brakes” on the enthusiasm that united providers and the public in support of a medical industry that strived to translate the proliferation of biomedical breakthroughs into an improvement in people’s lives.

Jerry Neighbor, Bert Neighbor’s son, developed abdominal pain in 1978. Because Blue Cross no longer paid for in-hospital diagnostic testing, his physician ordered outpatient x-ray studies. When colon cancer was discovered, Jerry Neighbor was admitted to Metropolitan Hospital on the morning of his surgery. His total hospital stay was 9 days, 6 days shorter than his father’s stay in 1962. Since 1962, medical care costs had risen by approximately 10% per year. Blue Cross paid Metropolitan Hospital $460 for each of the 9 days Jerry Neighbor spent in the hospital, for a total cost of $4140. The Blue Cross board of directors, which in 1977 included for the first time more business than hospital representatives, submitted a formal proposal to the regional health planning agency to reduce the number of hospital beds in the region, in order to keep hospital costs down. The planning agency board had a majority of hospital and physician representatives, and they voted the proposal down.

In the early 1970s, the United States fell from its postwar position of economic dominance, as Western Europe and Japan gobbled up markets (not only abroad but in the United States itself) formerly controlled by US companies. The United States’ share of world industrial production was dropping, from 60% in 1950 to 30% in 1980. Except for a few years during the mid-1980s, inflation or unemployment plagued the United States from 1970 until the early 1990s.

The new economic reality was a critical motor of change in the health care system. With less money in their respective pockets, individual health care consumers, business, and government became concerned with the accelerating flow of dollars into health care. Prominent business-oriented journals published major critiques of the health care industry and its rising costs (Bergthold, 1990). A new concern for primary care, which seemed underemphasized in relation to specialty and hospital care, spread within the health professions. These developments produced tensions within the health industry itself.

Faced with Blue Cross premium increases of 25% to 50% in a single year, angry Blue Cross subscribers protested at state hearings in eastern and midwestern states and challenged hospital control over Blue Cross boards (Law, 1974). Some state governments began to regulate hospital construction, and a few states initiated hospital rate regulation. The federal government established a network of health planning agencies, in an attempt to slow hospital growth. Peer review was established to monitor the appropriateness of physician services under Medicare. Thus, the purchasers took on an additional role as health care regulators. But the health care industry resisted these attempts by purchasers to control health care costs. Medical inflation continued at a rate far above that of inflation in the general economy (Starr, 1982).

Nonetheless, these early initiatives from the purchasers made an impact on the provider–insurer pact. As pressure mounted on insurers not to increase premiums, insurers demanded that services be provided at lower cost. Blue Cross, widely criticized as playing the role of an intermediary that passed increased hospital costs on to a helpless public, legally separated from the American Hospital Association in 1972 (Law, 1974). State medical societies were forced to relinquish some of their control over Blue Shield plans. Conflicts erupted between providers and insurers as the latter imposed utilization review procedures to reduce the length of hospital stays. Hospitals, which had hitherto purchased the newest diagnostic and surgical technology desired by physicians or their medical staff, began to deny such requests because insurers would no longer guarantee their reimbursement. Moreover, the glut of hospital beds and specialty physicians, which had been produced by the attractive reimbursements of the 1960s and the influence of the biomedical model on medical education (see Chapter 5), turned on itself as half-empty hospitals and half-busy surgeons began to compete with one another for patients. Strains were showing within the provider–insurer pact.

By the late 1970s, the deepening of the economic crisis created a nationwide tax revolt. As a result, governments attempted to reduce spending on such programs as health care (Kuttner, 1980). But major change was still awaiting the arrival of the other powerful purchaser: business.

In 1989, Ryan Neighbor, Jerry Neighbor’s brother, became concerned when he noticed blood in his stools; he decided to see a physician. Six months earlier, his company had increased the annual health insurance deductible to $1000, which could be avoided by joining one of the HMOs offered by the company. Ryan Neighbor opted for the Blue Cross HMO, but his family physician was not involved in that HMO, and Mr. Neighbor had to pick another physician from the HMO’s list. The physician diagnosed colon cancer; Ryan Neighbor was not allowed to see the surgeon who had operated on his brother but was sent to a Blue Cross HMO surgeon. While Mr. Neighbor respected Metropolitan Hospital, his surgery was scheduled at Crosstown Hospital; Blue Cross had refused to sign a contract with Metropolitan when the hospital failed to negotiate down from its $1800 per diem rate. Ryan Neighbor’s entire Crosstown Hospital stay was 5 days, and the HMO paid the hospital $7500, based on its $1500 per diem contract.

The late 1980s produced a severe shock: The cost of employer-sponsored health plans jumped 18.6% in 1988 and 20.4% in 1989 (Cantor et al, 1991). Between 1976 and 1988, the percentage of total payroll spent on health benefits almost doubled from 5% to 9.7% (Bergthold, 1991). In another development, many large corporations began to self-insure. Rather than paying money to insurance companies to cover their employees, employers increasingly took on the health insurance function themselves and used insurance companies only for claims processing and related administrative tasks. In 1991, 40% of employees receiving employer-sponsored health benefits were in self-insured plans. Self-insurance placed employers at risk for health care expenditures and forced them to pay more attention to the health care issue. These three developments (ie, a troubled economy, rising health care costs, and self-insurance) catapulted big business into the center of the health policy debate, with cost control as its rallying cry. Business, the major private purchaser of health care, became the motor driving unprecedented change in the health care landscape (Bergthold, 1990). Business threw its clout behind managed care, particularly HMOs, as a cost-control device. By shifting from fee-for-service to capitated reimbursement, managed care could transfer a portion of the health expenditure risk from purchasers and insurers to providers (see Chapter 4).

Individual health care consumers, in their role as purchasers, also showed some clout during the late 1980s. Because employers were shifting health care payments to employees, labor unions began to complain bitterly about health care costs, and major strikes took place over the issue of health care benefits. More than 70% of people polled in a 1992 Louis Harris survey favored serious health care cost controls (Smith et al, 1992). The growing tendency of private health insurers to reduce their risks by dramatic premium increases and policy cancellations for policyholders with chronic illnesses created a series of horror stories in the media that turned health insurance companies into highly unpopular institutions.

During the 1980s, the government was facing the tax revolt and budget deficits, and it took measures designed to slow the rising costs of Medicare and Medicaid, with limited success. The 1983 Medicare Prospective Payment System (diagnosis-related groups [DRGs]) reduced the rate of increase of Medicare hospital costs, but outpatient Medicare costs and costs borne by private purchasers escalated in response. In 1989, Medicare physician payments were brought under tighter control, resulting in Medicare physician expenditures growing at only 5.3% per year from 1991 to 1993, compared with 11.3% per year from 1984 to 1991 (Davis and Burner, 1995). Numerous states scaled back their Medicaid programs, but because of the economic recession and the growing crisis of uninsurance (see Chapter 3), the federal government was forced to expand Medicaid eligibility, and Medicaid costs rose faster than ever before. Governments began to experiment with managed care for Medicare and Medicaid as a cost-control device.

The most significant development of the 1980s was the growth of selective contracting. Purchasers and insurers had usually reimbursed any and all physicians and hospitals. Under selective contracting, purchasers and insurers choose which providers they will pay and which they will not (Bergthold, 1990). In 1982, for example, California passed a law bringing selective contracting to the state’s Medicaid program and to private health insurance plans. The law was passed because large California corporations formed a political coalition to challenge physician and hospital interests, and because insurers deserted their former provider allies and joined the purchasers (Bergthold, 1990). The message of selective contracting was clear: Purchasers and insurers will do business only with providers who keep costs down. This development, especially when linked with capitation payments that placed providers at risk, changed the entire dynamic within the health care industry. For patients, it meant that like Ryan Neighbor, they had lost free choice of physician because employers could require employees to change health plans and therefore physicians. For the health care industry, selective contracting meant fierce competition for contracts and the crumbling of the provider–insurer pact.

As a result of the purchasers’ revolt, managed care became a burgeoning movement in US health care. By 1990, 95% of insured employees were enrolled in some form of managed care plan, including fee-for-service plans with utilization management, preferred provider organizations (PPOs), and HMOs. The growth of managed care plans, especially HMOs, competing against one another for contracts with business and the government, changed the entire political topography of US health care (Table 16–2).

Table 16–2. Historical overview of US health care

In 1994, Pamela Neighbor, Ryan’s cousin, developed constipation. Earlier that year, her law firm had switched from Blue Cross HMO to Apple a Day HMO because the premiums were lower; all employees of the firm were forced to change their physicians. Apple a Day contracted only with Crosstown Hospital, whose rates were lower than those of Metropolitan, resulting in Metropolitan losing patients and closing its doors. Ms. Neighbor’s new physician diagnosed colon cancer and arranged for her admission to Crosstown Hospital for surgery. The physician’s office was across the street from the now-closed Metropolitan Hospital. Four days before the procedure, a newspaper headline proclaimed that Apple a Day and Crosstown had failed to agree on a contract. The colonoscopy was canceled. Pamela Neighbor waited to see what would happen next.

During the 1990s, many metropolitan areas in the United States, and some smaller cities and towns, experienced upheavals of their medical care landscape. Independent hospitals began to merge into hospital systems. In the most mature managed care markets, three or four health care networks were competing for those patients with private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid. Selective contracting allowed purchasers and insurers to set reimbursement rates to health care providers. HMOs that demanded higher premiums from employers did not get contracts and lost their enrollees. Providers who demanded higher payment from HMOs were cut out of HMO contracts and lost many of their patients.

Selective contracting tended to disorganize rather than organize medical care patterns. Physicians were forced to admit patients from one HMO to one hospital and those from another HMO to a different hospital. Laboratory, x-ray, and specialist services close to a primary care physician’s office were sometimes not covered under contracts with that physician’s patients’ HMO, forcing referrals to be made across town. In one highly publicized case with a tragic outcome, the parents of a 6-month-old infant with bacterial meningitis were told by their HMO to drive the child almost 40 miles to a hospital that had a contract with that HMO, passing several high-quality hospitals along the way (Anders, 1996).

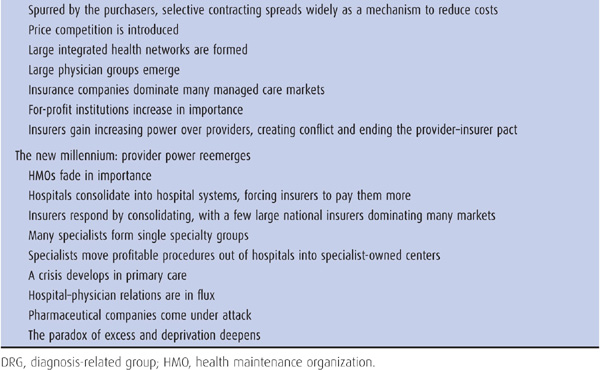

The 1990s was a period of purchaser dominance over health care. The federal government stopped Medicare inflation in its tracks through the tough provisions of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. The average annual growth in Medicare expenditures declined from 12% in the early 1990s to zero in 1999 and 2000. On the private side, employers bargained hard with HMOs, causing insurance premium annual growth to drop from 13% in 1990 to 3% in 1995 and 1996. In California, employer purchasers consolidated into coalitions to negotiate with HMOs. The Pacific Business Group on Health, negotiating on behalf of large companies for 400,000 employees, and California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS), representing a million public employees, forced HMO premiums to go down during the 1990s. Enrollment in HMOs grew rapidly in the 1990s, expanding from 40 million enrollees in 1990 to 80 million in 1999.

In 2005, Pamela Neighbor, who was feeling well, made an appointment for her yearly colon cancer follow-up. The IPA in which her physician practiced had recently gone bankrupt and closed its doors. Ms. Neighbor’s employer had switched its employees from Apple a Day Insurance Company’s HMO product to Apple a Day PPO, allowing patients to access most of the physicians and all the hospitals in town. Ms. Neighbor had a difficult time finding a new primary care physician, and when she found one, it took several weeks to get an appointment. Eventually, a colonoscopy was scheduled at a diagnostic center owned by a group of gastroenterologists. She was diagnosed with a second colon cancer and her primary care physician arranged for her admission to Crosstown Hospital. Ms. Neighbor never saw her primary care physician in the hospital; a surgeon plus a salaried inpatient physician called a hospitalist cared for Ms. Neighbor during her 4-day hospital stay. Apple a Day paid Crosstown Hospital $7200, $1800 per diem.

Several trends characterize the first decade of the twenty-first century: the counter-revolution by providers, consolidation in the health care market, growing power of specialists and specialty services, increasing physician–hospital tensions, an emerging crisis in primary care, growing criticism of pharmaceutical companies, and a steady increase in the uninsured and underinsured population.

In the mid-1990s, most health care analysts were certain that tightly managed care—with purchasers and insurers dominating health care providers—had become the new paradigm for health care in the United States. By 2001, this certainty had evaporated (Robinson, 2001). From 2000 to 2010, HMO enrollment dropped from 32% to 19% of insured employees, with only 19% of HMOs affiliated with an integrated delivery system. During those years, preferred provider organization (PPO) enrollment grew from about 30% to 60% of insured employees (Claxton et al, 2010). Tightly managed care was faltering.

The first decade of the twenty-first century could be called the era of the provider counter-revolution. Hospitals consolidated into hospital systems and demanded large price increases from insurers. Physicians balked at tight managed care contracts. Negotiations between health care providers and insurers became increasingly hostile, with one side or the other often refusing to sign contracts. As hospitals and providers gained an upper hand in negotiations with health plans, HMOs in turn demanded more money from employers. Insurance premiums for family coverage went from an average of $6,000 per year in 2000 to almost $14,000 in 2010, with virtually no difference between HMO and PPO premiums (Claxton et al, 2010). Purchasers lost faith that HMOs could control costs.

At the same time, individuals have been stuck with a greater proportion of health care costs. Twenty percent of insured employees, up from 10% in 2006, have a deductible of $1000 or more for individual coverage. The percent of insured employees with high-deductible plans has risen from 5% in 2006 to 13% in 2010; in a typical high-deductible plan, employees pay over $3000 for their portion of the premium plus a deductible of $4000 (Claxton et al, 2010). Employees’ out-of-pocket health care costs increased 34% from 2004 to 2007 (Gabel et al, 2009).

The intense competition of the 1990s stimulated consolidation among insurers and providers, as each vied to improve its bargaining power. Large HMOs bought up smaller ones and merged with one another. In most states, three large insurance companies control more than 60% of the market (Robinson, 2004). These companies generally offer a variety of products including HMO, PPO, high deductible, and Medicare Advantage plans. Three huge insurers, all for-profit, are Wellpoint with 34 million enrollees in 2010, United Healthcare with 32 million, and Aetna with 18 million.

Providers also consolidated. By 2001, 65% of hospitals were members of multihospital systems or networks (Bazzoli, 2004), and consolidation continued, though at a slower pace, through 2008. In many cities, two or three competing hospital systems encompass all hospitals. Hospital prices often rise rapidly after consolidation has taken place since payers are forced to contract with dominant hospital systems (Vogt, 2009). Specialists increasingly joined single-specialty groups, with the majority of cardiologists or orthopedists in some cities belonging to a dominant group (Liebhaber and Grossman, 2007). Private primary care and specialty practices are being acquired by hospital systems hoping to increase their market clout (Iglehart, 2011).

Consolidation went hand in hand with organizations converting from nonprofit to investor-owned “for-profit” status as they sought to raise capital for buy-outs, market expansion, and organizational infrastructure. For decades, for-profit companies have played a prominent role in health care, with the rise in the 1970s of the “medical–industrial complex” (Relman, 2007). For-profits, which owned 35% to 40% of health care services and facilities in 1990, expanded their reach during the 1990s. Nine of the largest 10 HMOs were for-profit by 1994. HMO stocks soared in the early 1990s and executives were rewarded with enormous compensation packages (Anders, 1996). Already in 1990, 77% of nursing homes and 50% of home health agencies were for-profit. Between 1993 and 1996, more than 100 nonprofit hospitals were taken over by forprofit hospital chains, though several financial scandals slowed down this trend. For-profit hospitals provide less charity care, treat fewer Medicaid patients, have higher administrative costs, and lower quality than nonprofit hospitals (Relman, 2007). By 2009, most specialty hospitals, imaging centers, ambulatory surgery centers were investor-owned (Relman, 2009).

That hospitals, physicians, and other providers respond to financial incentives is hardly a new phenomenon. As discussed in Chapter 5, more lucrative third-party payment for procedurally oriented specialty care has been one of the key factors shaping a physician workforce weighted toward nonprimary care fields and a hospital sector filled with tertiary care facilities. However, twenty-first-century health care in the United States is becoming characterized by a single-minded quest for profitability that is threatening traditional notions of professionalism and community service. Emblematic of this trend is the emergence of a new type of for-profit hospital, the specialty hospital fully or partially owned by groups of specialist physicians. As of 2010, 265 of these hospitals existed in the United States, typically limiting their services to cardiac and orthopedic procedures—service lines that are well reimbursed (Perry, 2010). Physician owners of these hospitals doubly benefit financially, receiving income from both the payment for the services they directly provide and their share of hospital profits. Moreover, physician owners often channel well-insured patients from nonprofit general hospitals to their own for-profit specialty hospitals. In one example, 16 cardiac surgeons and cardiologists shifted their patients with heart disease from a university medical center to a new hospital only caring for patients with heart disease; the number of cardiac surgeries performed at the university medical center dropped from over 600 to below 200 between 2002 and 2004, resulting in the loss of $12 million in revenues. Uninsured patients continued to have cardiac procedures at the university hospital (Iglehart, 2005). For the community as a whole, the opening of a cardiac hospital is associated with increased rates of coronary revascularization (coronary artery bypass surgery and angioplasty), raising questions about whether all the additional procedures are medically appropriate (Nallamothu et al, 2007). Because of these problems with specialty hospitals, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 barred new specialty hospitals from receiving Medicare payments (Perry, 2010).

Similar financial incentives have attracted specialist physicians to set up many thousands of ambulatory surgery, diagnostic, and imaging centers that they own. A growing proportion of profitable services—cataract surgery and orthopedic procedures, diagnostic studies such as colonoscopies, and CT or MRI studies—have been shifted from hospital facilities to these physician-owned ambulatory centers. As with specialty hospitals, physicians earn income from both the services they directly provide and the facility’s profits. Because general hospitals formerly earned considerable income from these procedures, this phenomenon has created major tensions between hospitals and specialists (Berenson et al, 2006b). The common practice of physicians referring patients for imaging tests at a facility owned by the same physician is associated with higher volumes of imaging services, increasing costs, and exposing patients to unnecessary radiation (Sunshine and Bhargavan, 2010).

Single-specialty groups have grown markedly since the late 1990s. Two major drivers of this growth are (1) the ability of organized specialists with market power in a local area to negotiate for high reimbursement rates from insurers and (2) the bringing together of capital to invest in specialist-owned surgery, diagnostic, and imaging centers. As a result of these trends, the income of specialists who offer procedural or imaging services has far outpaced the growth in earnings for primary care physicians (Bodenheimer et al, 2007). Multispecialty groups, which include primary care physicians and tend to have the best scores on quality report cards, are not growing in part because specialist physicians in multispecialty groups are expected to share their high revenues with lower-reimbursed primary care physicians (Casalino et al, 2004; Mehrotra et al, 2006).

Nonprofit community hospitals are responding to competition from specialist physicians by creating “specialty service lines” to attract specialist physicians and well-insured patients to their institutions. To create capacity for these profitable service lines, hospitals are de-emphasizing traditional medical-surgical wards. Whether the hospital is a nonprofit community hospital, a for-profit hospital, or a physician-owned specialty hospital, filling a hospital bed with a patient receiving an organ transplant or spine surgery is much more financially rewarding than filling the same bed with an elderly patient with pneumonia and heart failure, even if the latter patient has insurance. Strategic planning by hospitals increasingly focuses on how to maximize the most profitable service lines, rather than on how to provide the services most needed in the community (Berenson et al, 2006a).

Compounding this situation is the weakening claim hospitals can make on physicians for community service. Surgeons, diagnostic cardiologists, gastroenterologists, ophthalmologists, and radiologists can successfully run a medical practice without ever setting foot in a hospital by focusing their work on ambulatory centers of which these physicians are owners. Because these specialists no longer need the hospital, they feel little obligation to be on call for hospital emergency departments or for patients in intensive care. Hospitals are forced to pay specialists large sums to provide nighttime emergency department backup or are employing specialists to perform the duties formerly done for free by specialists on the hospital medical staff. The divorce of physicians from the community hospital is not limited to specialists. As a result of the hospitalist movement, many primary care physicians are never seen in a hospital. Hospitalists are physicians who specialize in the care of hospitalized patients. Most are employees of a hospital or hospital system; others are members of single-specialty hospitalist groups, which contract with hospitals to supply hospitalist physicians. Hospitalists are the fastest growing specialty in the history of medicine in the United States; the 500 hospitalists existing in 1997 have multiplied into about 30,000 hospitalists in 2010.

The quest for profitability is further aggravating the primary care-specialist imbalance in the physician workforce in the United States. In 2007, only 7% of US medical school graduates planned careers in adult primary care, with an adult primary care physician shortage projected at about 40,000 by 2020. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants help mitigate this shortage but their numbers are not sufficient to solve the problem. As a result, patients are having increasing difficulty gaining timely access to primary care or finding a new primary care physician. Although the causes of the declining career interest in primary care are multifactorial, the gap between primary care and specialty incomes is one reasons why growing numbers of US medical students and residents—many of whom have more than $150,000 in personal debts from medical school expenses—have turned away from careers in primary care (Bodenheimer and Pham, 2010).

These trends pull health care in the United States farther away from a primary care-based, community-responsive model. Evidence suggests that this trend will fuel continued inflation in health care costs without yielding commensurate benefits for the health of the public. A major reform of payment policies in the United States, along with a rethinking of the role of investor-owned enterprises in health care, will be required in order to realign financial incentives with the values that make for a well-functioning system.

The rising tensions among purchasers, insurers, and providers spilled over to engulf health care’s major supplier: the pharmaceutical industry. In 1988, prescription drugs accounted for 5.5% of national health expenditures. With 71% of drug costs borne out of pocket by individuals and only 18% paid by private insurance plans, these costs had little impact on insurers. In contrast, by 2009, prescription drug costs had risen to 10.1% of total health expenditures, with only 21% paid out of pocket, the rest covered by employers, insurers, and governmental purchasers. The growing cost of pharmaceuticals for the elderly became a major national issue. Because of its unaffordable prices and high profits, the pharmaceutical industry was becoming public enemy number one (Spatz, 2010).

For years, drug companies have been the most profitable industry in the United States, earning net profits after taxes close to 20% of revenues (19.3% in 2008), compared with 5% for all Fortune 500 firms. The pharmaceutical industry argues that high drug prices are justified by its expenditures on research and development of new drugs, yet the National Science Foundation estimates that true R&D spending is half of what the pharmaceutical industry claims (Congressional Budget Office, 2006). R&D for the largest drug companies consumed 14% of revenues in 2002, while marketing and administration accounted for 33% and after-tax net profits 21% (Reinhardt, 2004). Unlike many nations, the US government does not impose regulated prices on drugs; as a result of drug industry lobbying, the Medicare prescription drug coverage law passed in 2003 forbid the government to regulate drug prices (see Chapter 2). From 2006 to 2008, the health industry spent more money on lobbying than any other sector of the economy, and the drug industry was the largest contributor within the health industry (Steinbrook, 2008).

Companies developing a new brand-name drug enjoy a patent for 20 years from the date the patent application is filed, during which time no other company can produce the same drug. Once the patent expires, generic drug manufacturers can compete by selling the same product at lower prices. Some drug companies have waged legal battles to delay patent expirations on their brand name products or have paid generic drug manufacturers not to market generic alternatives (Stolberg and Gerth, 2000; Hall, 2001). In addition, the industry attempts to persuade physicians and patients to use brand-name products, spending $7 billion in 2009 on sales representatives’ visits to physicians, journal advertising, and sponsorship of professional meetings, plus $4 billion on direct-to-consumer television ads (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). The federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has sent hundreds of letters to drug manufacturers, citing advertising violations including minimizing side effects and exaggerating benefits (Donohue et al, 2007). Four out of five physicians have some type of financial relationship with the pharmaceutical industry, ranging from accepting gifts to serving as a paid lecturer on behalf of a company. These physician–industry relationships influence physicians to prescribe new drugs that are the most expensive and whose safety has not been adequately evaluated (Campbell, 2007). Drug firms may pay medical school faculty physicians tens of thousands of dollars to participate on their corporate boards (Lo, 2010).

Most trials to determine the efficacy of prescription drugs are funded by that drug’s manufacturer, and trials funded by industry are more likely than those with nonindustry funding to report results favorable to the funding company (Bero, 2007). Yet physicians base treatment decisions on these trials, which inform clinical practice guidelines. Authors of clinical practice guidelines often have ties to the pharmaceutical industry (Abramson and Starfield, 2005). From 2006 to 2010, at least 18 relatively new drugs were removed from the market because of serious side effects; in some cases, the manufacturer knew of the problems but hid them from the FDA and the public; in other cases, the FDA ignored the evidence. Some members of FDA committees recommending approval of a drug have ties to that drug’s manufacturer, and these members are often not recused from the process (Angell, 2004).

These revelations have tainted the image of the pharmaceutical industry in the eyes of the medical profession and the public. Private health insurance companies have mounted the most effective response to the drug industry by creating tiered formularies in which generic drugs have lower copayments than brand-name drugs. As a result, 75% of all prescriptions filled in the United States in 2009 were for generic products (Spatz, 2010). This development has slowed the rate of growth of pharmaceutical costs. However, some brand-name drug companies are starting to produce generics, and the generic industry is starting to consolidate into fewer and larger companies; these trends could mean that generic prices may rise to levels not far below brand name prices.

The health care system has been dominated by a series of unstable power relationships among purchasers, insurers, providers, and suppliers. One of these actors may take center stage for a time, only to be pushed into the corner by another actor. Which entity has the leverage to get its way varies from city to city, depending on who has consolidated into larger institutions. Larger institutions can (in the case of providers and suppliers) demand to receive more money, or (in the case of purchasers and insurers) succeed in paying out less money. Patients continue to be at the mercy of these powerful institutions, as health care costs rise and as individuals bear a greater share of those costs.

Inequities in insurance coverage and in access to care continue, and cost control remains elusive. Whether the Affordable Care Act of 2010 will succeed in improving access and containing costs remains to be seen. The drive to make money—whether for specialist physicians, for-profit and nonprofit hospitals, insurers, or pharmaceutical companies—increasingly determines what happens in health care. For physicians, this economic motivation may clash with the professional commitment to patient welfare. The commitment of all health care professionals to the ethical principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, patient autonomy, and distributive justice is tested on a daily basis in the profit-oriented environment of twenty-first century health care in America.

Chapter 1 introduced the paradox of excess and deprivation: Some people get too little care while others receive too much, which is costly and may be harmful. The first decade of the twenty-first century saw a sharpening of this paradox, with the number of uninsured climbing from 40 million to 50 million at the same time as the increasing number of specialist physicians owning their facilities was associated with growing volumes of expensive procedures, many of questionable appropriateness (Brownlee, 2007; Welch et al, 2011). Overcoming this paradox remains the fundamental challenge facing the health care system of the United States.

Abramson J, Starfield B. The effect of conflict of interest on biomedical research and clinical practice guidelines. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:414.

Anders G. Health Against Wealth: HMOs and the Breakdown of Medical Trust. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1996.

Angell M. The Truth About the Drug Companies. New York: Random House; 2004.

Bazzoli G. The corporatization of American hospitals. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2004;29:885.

Berenson RA et al. Specialty service lines: Salvos in the new medical arms race. Health Affairs Web Exclusive. 2006a; 25(5):w337.

Berenson RA et al. Hospital–physician relations: Cooperation, competition, or separation? Health Aff Web Exclusive. 2006b;26(1):w31.

Bergthold L. Purchasing Power in Health. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1990.

Bergthold L. The fat kid on the seesaw: American business and health care cost containment, 1970–1990. Annu Rev Public Health. 1991;12:157.

Bero L et al. Factors associated with findings of published trials of drug–drug comparisons. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e184.

Bodenheimer T et al. The primary care-specialty income gap: Why it matters. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:301.

Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: Current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff. 2010;29:799.

Brownlee S. Overtreated. Why Too Much Medicine Is Making Us Sicker and Poorer. New York, NY: Bloomsbury; 2007.

Campbell EG. Doctors and drug companies—scrutinizing influential relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1796.

Cantor JC et al. Business leaders’ views on American health care. Health Aff. 1991;10(1):98.

Casalino L et al. Growth of single-specialty medical groups. Health Aff. 2004;23(2):82.

Claxton G et al. Health benefits in 2010: Premiums rise modestly, workers pay more toward coverage. Health Aff. 2010;29:1942.

Congressional Budget Office. Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry. 2006. www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/76xx/doc7615/10-02-DrugR-D.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2011.

Davis MH, Burner ST. Three decades of Medicare: What the numbers tell us. Health Aff. 1995;14(4):231.

Donohue JM et al. A decade of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:673.

Gabel JR et al. Trends in underinsurance and the afford-ability of employer coverage, 2004–2007. Health Aff. 2009;28:w595.

Hall SS. Prescription for profit. New York Times Magazine. March 11, 2001.

Iglehart JK. The emergence of physician-owned specialty hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:78.

Iglehart JK. Doctor-workers of the world, unite! Health Aff. 2011;30:556.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Prescription drug trends, 2010. www.kff.org.

Kennedy P. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Random House; 1987.

Kuttner R. Revolt of the Haves. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1980.

Law SA. Blue Cross: What Went Wrong? New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1974.

Liebhaber A, Grossman JM. Physicians moving to mid-sized, single-specialty practices. Tracking Report No. 18. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; August 2007.

Light DW, Warburton R. Demythologizing the high costs of pharmaceutical research. Biosocieties. 2011;6:34.

Lo B. Serving two masters—conflicts of interest in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:669.

Mehrotra A et al. Do integrated medical groups provide higher-quality medical care than individual practice associations? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:826.

Nallamothu BK et al. Opening of specialty cardiac hospitals and use of coronary revascularization in Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2007;297:962.

Perry JE. A mortal wound for physician-owned specialty hospitals? 2010. www.academia.edu.

Reinhardt UE. Reorganizing the financial flows in US health care. Health Aff. 1993;12(suppl):172.

Reinhardt UE. An information infrastructure for the pharmaceutical market. Health Aff. 2004;23(1):107.

Relman AS. A Second Opinion. Rescuing America’s Health Care. New York, NY: Public Affairs; 2007.

Relman AS. The health reform we need & are not getting. New York Rev Books. 2009;56(11):38.

Robinson JC. The end of managed care. JAMA. 2001;285:2622.

Robinson JC. Consolidation and the transformation of competition in health insurance. Health Aff. 2004;23(6):11.

Smith MD et al. Taking the public’s pulse on health system reform. Health Aff. 1992;11(2):125.

Spatz ID. Health reform accelerates changes in the pharmaceutical industry. Health Aff. 2010;29:1331.

Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books; 1982.

Steinbrook R. Campaign contributions, lobbying, and the US health sector. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1313.

Stolberg SG, Gerth J. How companies stall generics and keep themselves healthy. NY Times. 2000.

Sunshine J, Bhargavan M. The practice of imaging self-referral doesn’t produce much one-stop service. Health Aff. 2010;29:2237.

Vogt WB. Hospital Market Consolidation: Trends and Consequences. National Institute for Health Care Management. November 2009. http://nihcm.org/pdf/EV-Vogt_FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2011.

Welch HG et al. Overdiagnosed. Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2011.