The May-Day Festival in the Year 1970

The May-Day Festival in the Year 1970

‘Optimus’, 1911

On April 29, 1970, the “Volkstribüne,” official organ of the Socialist administration for the district of Lower Austria, published the customary order of the President that all work should cease on the First of May. Only such work as was necessary for the festal celebration of that day was to be allowed, but even with regard to the latter the President’s message desired that the decoration of the streets and the preparations for the festival should, as far as possible, be carried out on the preceding day.

On the morning of the First of May the great garden city of Vienna, which now extends from Stockerau to Mödling,1 lay in deep repose. The many bright-coloured little houses, in Cotta style,2 each surrounded by a small green garden, had been already decked out the night before with red flags, and so it was half past six o’clock—the sun had long ago risen brilliantly—before the first of the green blinds in the workers’ little one-family houses were drawn up.

Already the evening before the young people had planted flag-staffs between the blooming chestnut trees, and many hundreds of red flags were already waving merrily in the breeze. The regular roads were strewn with freshly mown grass, and in every district—from Stockerau to Mödling—a large platform was erected in the principal square, with a small platform and speakers’ desk opposite to it, which was also to be used by the conductor of the district orchestra.

At 7.20 a.m. the motors from the milk co-operative and other food supply stores, which from old association still kept the name of “hammer-works,” ran through the workers’ cottages, and deposited in the breakfast receptacle which is built into the front of each house the necessary provisions for the festal day, milk, eggs, bacon, or fish, fruit, vegetables, coffee, cigars, etc., according to the orders given the preceding day at the food centre. At 8 o’clock smoke was already rising from the chimneys of all the pretty houses, and whoever entered any of the clean, white-washed halls was met by an aroma of fresh coffee and newly-baked bread. And at this time many a housewife might be seen going up and down the garden with large scissors choosing the peonies and tulips which were destined for the festal board.

At 8.30 500 bands of music marched through every division of the garden city, except, of course, the inner quarters, on feast days resembling cities of the dead, which are exclusively given up to workshops, factories and offices. The underground railway, which takes one in 4 to 6 minutes from, for instance, the St. Viet garden city to the factory quarter of Brigittenau,3 rests to-day. But at certain headquarters of each district one can—after previously giving notice at the traffic centre—have one of the motors which stand there, which indeed one must drive oneself, in order to do which it is necessary to have passed the chauffeur’s examination, a thing which is, in general, done by one member of each family. There is, however, no very great demand for them, most of the comrades preferring to pass the day with companions in the same district, to which they have been drawn in order to be near the friends of their choice.

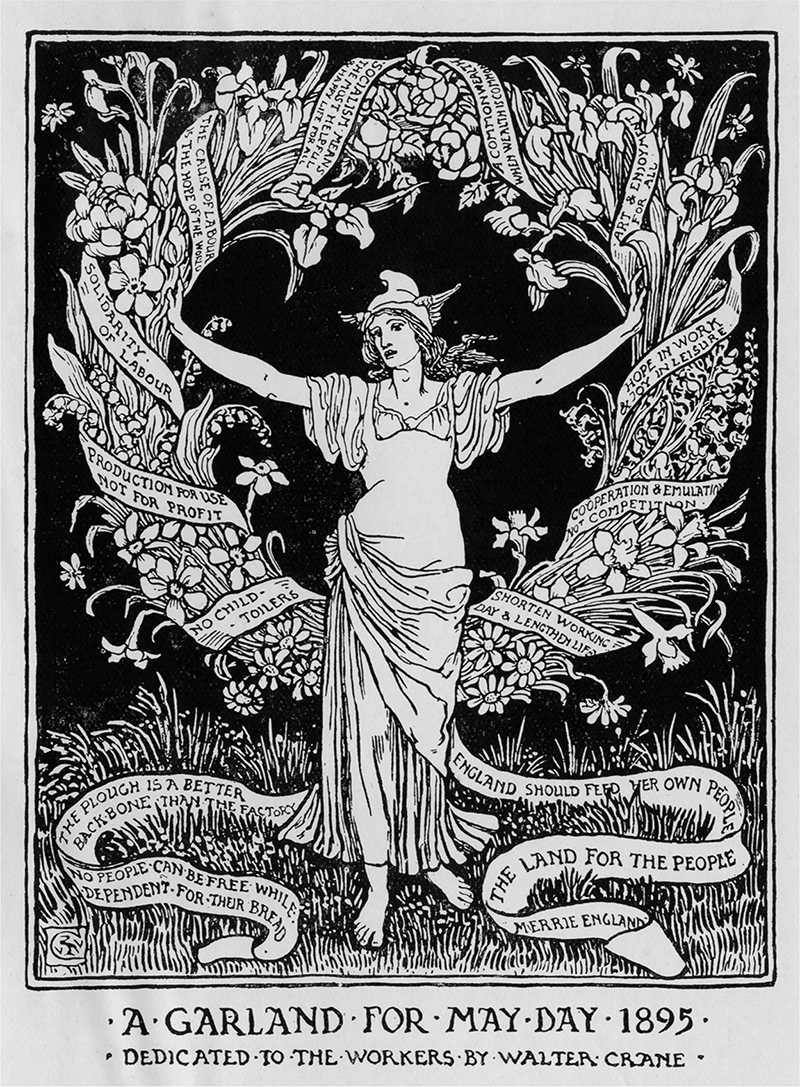

Fig. 9. Walter Crane’s poster for the International Socialist Trade Union Congress (1896). Private collection, photo © Ken Welsh / Bridgeman Images.

The silver trumpets of the bands bring jubilation, noise, movement, confusion into the quiet garden city streets. In a twinkling the battalions of the “Youth” were drawn up, and, headed by the bands, marched rank after rank to the platforms on the public place. The orchestra played historical battle songs from the old departed times of oppression, and the choirs of youths chimed in with clear voices. By 9 o’clock everybody was on their feet; 800 platforms in all the great squares were crowded, and from millions of throats now rose a real true hymn of the people into the stir, a song of joy and of labour, a paean of youth and strength, a song sung by awakened mankind in its own honour.

Then all became still.

An old man mounted the tribune (the procedure was the same at all the centres of festivity) and spoke: “Comrades, brothers, fellow citizens! Let no man to-day forget the times of struggle! You rosy-cheeked youths, from out whose eyes life sparkles, you know not how black and threatening it was, here on earth, even as late as 60 years ago. You never knew the horrors of exploitation, the misery of those who had deadened themselves with drugs, the hopelessness of those who were utterly weary. We elders, who were witnesses of that dread epoch, we are dying out. But yet to-day I remember with a shudder the days of the horrible tenements in the narrow alleys of the large towns, of the neglected children roaming naked about the streets, of the torture of unemployment and of dependence on an employer—that life led by millions of proletarians, which was no life, or would not have been if it had not been spiritualized by the burning desire to destroy that world of oppression! You, who are growing up in light and sunshine, in the strength and fullness of a free life, think of the hell of capitalist society whose portals we have successfully broken down.”

The words, spoken with trembling lips by the old man, were listened to in breathless silence.

Then a young woman, slender as a girl, in a long flowing robe which showed the chaste beauty of her noble form, mounted the platform and spoke with impressive nobility of manner, without undue heat and yet full of life: “Comrades, sisters, brothers! The words of the fatherly veteran have sunk into our hearts. We know, indeed, that there was once a time of the madness of possession. We know that the soul was once fettered by the demons of selfishness. We know it, but we can no longer fully realize what it was. For how is it possible that human beings themselves should have maimed their own souls and bodies? How was it possible that thousands should slavishly serve one? How was it possible that, instead of becoming strong and free in light and air, well cared for and well educated, men should pine in pestilential air, in ugly homes, untaught and half-starved? At that time man only knew himself, and that made him small! We know that man and woman, flower and animal, the blade of grass in our garden and the stones on which we tread, are all parts of the same world, and only he who feels himself at one with all creation, he alone is worthy to be our brother. Whoso finds himself anew in others, whoso has conceived the great law of fellowship, he who will not tread down a blade of grass unnecessarily, whose glance caresses every child, he who feels and knows what is taking place in the soul of his neighbor, he is rich. To the slave of the vanished state of society his possessions formed a world, to us the whole world had become a possession!

No applause was heard. No evil look fell on that proud figure. But a thousand youthful, sparkling eyes looked at each other, filled with the noblest emulation to become prominent in the service of the whole.

Music struck up. The youths sang. The crowds then went leisurely home. In the group in which the old man walked someone pointed over to the factory district. “Yes, indeed,” the old fellow related, “the factories then were not worked by electro-dynamos as now; there was infernal black smoke in almost every workshop, and our hands were covered with soot; and where was there ever a chance that a gifted workman might study or ever leave the factory to be admitted to other social work? When his strength failed him—well then . . .”

But the old man had now reached his goal. They led him to the gate of the palace which bore the inscription “The Castle of Peace.” Such places 60 years ago, miserably arranged, were known as “poor-houses” or “alms houses.”4

The middle of the day was passed by each one in his own family circle. On each table was a beautiful bouquet. After dinner the old people lay themselves down in hammocks, the young ones went into summer-houses, taking with them this or that book from the central library which supplies every citizen daily, as gifts or loans, with the books he desires. The little ones ran to the great public playgrounds.

At 3 o’clock trumpet blasts called once more to the feast. Now the masses made a pilgrimage to the 50 great arena buildings, the people’s theatre, in which to-day festive performances, free to all, were held. The great orchestras played, glorious voices sang hymns of freedom, and at last the rising of the curtain disclosed the stage. Goethe’s “Faust,”5 still as ever the symbol of struggling humanity, was performed. Breathless stillness in the whole arena, a hundred thousand human beings feeling the words: “Wer immer strebend sich bemüht, den können wir erreten.”*

It is evening; the inner districts lie in darkness, but in the garden city quarters there are lights shining from many thousand houses. From the Kahlenberg6 thousands of rockets ascend flaming through the sky; on the Danube boats with bright red lamps are sailing. From the gardens before the houses sound violins and flutes; the children sing till they are tired. No drunkard reels through the peaceful streets. From the “Castle of Rest” may be heard the voice of a happy old man. He is weeping for joy.

* “Whoever struggles with difficulty himself to redeem, him we can save.”