VAUDEVILLE IN A BOX

Fourth among the great commercial interests of the United States, Kinematography, or the art of making motion pictures, and the several co-related branches of industry each contributing its portion to the harmonious whole, has shown a development that hitherto has not been equaled in the annals of business and that may well be termed the marvel of the Century…. It is generally agreed that it was somewhere ’round about the year 1896 that motion pictures began to show commercial possibilities in this country…. It was not until the year 1905, however, that the motion picture business hit its present slant towards prosperity…. Most everyone in the picture business today has witnessed the development of the exhibition business from the “store show,” which is rapidly passing, to the large and comfortable houses where the finest pictures are now shown. It was the multiplication of the “store show” that gave the motion picture business its impetus.

—Moving Picture World (1914)1

FROM ROUGHLY 1905 TO THE EARLY YEARS OF THE DEPRESSION, more theaters were built across the United States than at any other time in American history. While it could be traced back to the 1890s, the “store theater,” as it was generally called in the trade press, kicked off the building boom in 1905: between 1905 and 1910, the store theater saw a rapid rise in popularity and installations and, with this rise, the beginnings of movies as a primary form of entertainment for a majority of Americans. In this period claims were heard of the seemingly metastasizing growth of store theaters—in 1906 alone “thousands of store shows” (“Kinematography,” 176). There is no way to prove these numbers, not least because claims of exactly how many theaters were built in the first decade of the dedicated motion picture theater and concomitant numbers of increasing patronage are often contradictory, sometimes even from the same sources.2 Writing in 1910, Robert Grau, a theatrical producer, wildly claimed that motion pictures created “30,000 new places of amusement.”3 By 1916, the Exhibitors Herald would claim the more modest—and more likely—total of 18,000 theaters with a daily attendance of 16 million people.4 If there is exaggeration in this breathless boasting of numbers, it speaks to the genuine sense of excitement about something new happening.

A key expression of this excitement is one of the most repeated myths of the nickelodeon era, the seemingly improvised nature of the store theater, which served to explain its rapid proliferation: putting together a film theater was often portrayed as just a matter of hanging up a bedsheet at one end, positioning a projector at the other, and putting some chairs in-between. A 1914 Moving Picture World review of the development of the motion picture offered a typical description: “In the beginning stores could be rented at a low figure and the cost of two or three hundred folding chairs, a few yards of muslin and a projecting machine did not exceed five hundred dollars.”5 A more recent history of early exhibition claims, “A storefront theater could be set up almost on impulse.”6 If this ever were the case, and there are reasons to doubt it, this period did not last long. The novelty of the store theater lay in its architecture, but as a theatrical entertainment it was building on an existing form that required a degree of planning and deliberation.

Concurrent with but running counter to the origin myth was the great acclaim granted to Samuel Rothapfel, later famous as “Roxy,” in the trade press, which from early on presented him as someone to imitate.7 In 1910, Moving Picture World printed a brief story about the career of “Mr. S. L. Rothapfel,” whom it termed “the ideal exhibitor,” although he ran his theater “in a little city of 7,000 inhabitants situated in the coal mining region of Pennsylvania.” The World was so impressed with the fact that “out of this 7,000 Mr. Rothapfel gets 1,000 in his theater every day of the week,” that it gave him the opportunity of writing a couple of columns on exhibition in subsequent issues.8 While Roxy was emphatic about the need for fine projection—“Everybody work toward the screen” was his “motto”9—his greatest interest was in programming: “A very important item in careful management is the arrangement of programs. By this I mean the order in which the respective reels and songs are run.” He proposed an “ideal program” of three reels: first an “industrial,” a leisurely introduction to the entertainment; some escalation in vitality with a song (not specified, but likely accompanied by stereopticon slides following contemporary practice); “a splendid dramatic reel,” increasing the intensity of the program; and, finally, a comedy, so that the “audience will leave their seats all smiles and satisfaction.” As varied as this program is, Roxy finds a sense of unity in music: “Another thing I want to call attention to is that fact that not one minute during the entire performance should your music cease. Open with a waltz in a lively tempo and use the same during small intermissions, swinging into score arranged for pictures on signal from the operator [i.e., projectionist].”10 Clearly this was not slapdash exhibition, and Roxy even called for “a careful rehearsal of your show,” although film might seem to obviate such a need (“Observations by Wide-Awake Exhibitors,” 373).

If programming required such deliberation, it was because the store theater did not emerge as something different from vaudeville, but rather as an offshoot of it, a series of discrete acts arranged to create a sense of unity. Writing a laudatory response to Rothapfel’s articles, another exhibitor claimed that, like Rothapfel, he achieved “popularity” by “the care I always took in selecting a well balanced program,” an ability he derived from “many years’ experience in show business before moving pictures came around.” His final exhortation—“Remember, there are a lot of different tastes to please”—is a succinct statement of a vaudeville principle.11 The store theater effectively extended the reach of variety entertainment by putting it in a can and exhibiting it in a box, all of which could be accomplished without actual performers having to travel a circuit of cities and towns across the United States and without the elaborate architecture required to present them. If the store theater established vaudeville as a guiding principle for dedicated movie theaters, it was a principle that carried over into the movie palace era as well. This consistency was reflected in Rothapfel’s career: as he progressed from his small town to big city, from modest store theater to grand palace, the vaudeville aesthetic continued to guide his sense of what a movie show should be.12 The vaudeville inheritance, then, was not left behind when movies moved from the vaudeville theater into a different home: rather, it is key to the development of motion pictures and proved as central to the growth of the palace as it was to the store theater. However, as an architectural matter, the store theater was something very different, and aspects of that difference would impact on subsequent movie palace design.

A NEW ARCHITECTURE

Films of the store theater era have received intense scholarly scrutiny because it is a period of such extraordinary change in the films themselves. But since this is also a period of great change in the venues where movies were shown, we should at least consider if there was a connection between the spaces surrounding the screen and what was unreeling on the screen. Certainly, most commentators have correlated the sharp rise in production with the extraordinary number of store theaters, with their “daily change” policies, and this change is easiest to document empirically since it fits nicely in a supply-and-demand model. As Moving Picture World observed in 1914, “During the year 1906 thousands of store shows were opened and the demand for pictures was theretofore unheard of.”13 Moving Picture World did not see supply begin to keep up with demand until 1907, but that lag only serves to underscore that exhibition helped drive production.14 Other important changes were taking place in this period as well, and it is worth asking if exhibition could in any way influence these changes. Robert Allen has seen a correlation between the ascent of the nickelodeon and the rise to dominance of the narrative film: “Between 1907 and 1908, a dramatic change occurred in American motion picture production: in one year narrative forms of cinema (comedy and dramatic) all but eclipsed documentary forms in volume of production.”15 And Tom Gunning has located the beginnings of the “narrator system,” crucial to the development of American film style, in this period.16 I do not want to claim one-to-one causation, but it is likely not mere coincidence that all this was happening when the whole theatrical plant for exhibiting motion pictures underwent a radical change. At a minimum, we can say the advent of the store theater was a response to the kind of movies that were being made and the places they were being shown. But, once established, the store theaters made demands on the kinds of films being produced—and established limitations as well that, ultimately, led to their own demise.17

Most obviously, the period from the rise of the store theater to the rise of the movie palace coincides with the growing perception of motion pictures as a new and distinctive way of telling stories, effectively a form of theater available to an audience much larger than ever before, but also an audience that generally did not have access to theater previously. At a minimum, the store theater helped condition this new view since it was the store theater which proved film alone could be a primary attraction for audiences at very low cost. And it was here that the motion picture finally came into its own as a new art form. In a 1915 interview, Cecil B. DeMille “stated his belief that the photoplay, which he described as picturization of a dramatic theme, was developing into one of the great branches of world literature,” a claim that would have been inconceivable only a decade earlier.18 For example, in 1908, a Moving Picture World article stated that most people did not see motion pictures as art: “That the moving picture drama is an art, is a proposition as yet not well recognized by the public at large. That it has a genuine technique, largely in common with the acted drama yet in part peculiar to itself, is a proposition which seems not to be well recognized within the moving picture field itself.”19 Movies in the period of the store theater had begun to be seen as a new dramatic art. Whether consequently or coincidentally, new configurations of theatrical space accompanied this new art.

In 1906 Billboard commented on the rapid expansion of motion picture exhibition as something more than the store theater: “Store shows and five-cent picture theatres might properly be called the jack rabbit of the business of public entertaining—they multiply so rapidly.”20 Two kinds of theaters are instanced here, flagging a distinction not observed by histories of early exhibition, which tend to use “store theater,” “nickel theater,” and “nickelodeon” interchangeably. A focus on architectural form can explain this difference: following the rapid growth of the store theaters and very much as response to their success, existing theaters, both vaudeville and legitimate, were repurposed as nickelodeons. Why is this distinction significant? For one, the store theaters became the first dedicated film theaters.21 More radically, while the repurposed nickel theaters offered familiar theatrical spaces, the store theaters upended centuries of architectural conventions. In the process, they provided a way of thinking about movie theaters that would have a lasting impact on architectural form. The significance of the store theater, then, was threefold: as the first dedicated motion picture theater, it established cinema as a magnet in the urban landscape; it created a distinctive architectural form responsive both to the requirements of film viewing as well as the restrictions of its urban setting; and it radically altered spatial conventions, making theater less exclusive by demonstrating that virtually any interior space could be made theatrical.

In 1913, an architecture magazine, The Brickbuilder, announced a design contest for motion picture theaters. It revealed the winners in a 1914 issue with a supplement, “The Moving Picture Theatre Special Number,” entirely devoted to movie theaters.22 The contest specifications made clear that “A Moving Picture Theater” for The Brickbuilder meant in its dimensions and location a store theater, one occupying a double lot: “The building lot has a frontage of 50 feet and is 100 feet deep, bounded on either side by existing buildings. The building is to occupy the entire lot.”23 The store theater was acknowledged as a specific architectural form. Consequently, it received increasing attention as a distinctive theater building in trade journals and architecture magazines.24 Motion Picture News noted in 1914, “The permanency of motion pictures in the amusement field has resulted in specialization on photo play theatres by architects.”25 As early as four years before, an issue of Architect’s and Builder’s Magazine ran the first article on requirements for movie theater architecture, “The Moving Picture Theatre.”26 Throughout the decade, articles on movie theater architecture appeared with increasing frequency in all major architectural journals, although the movie palace would eventually effect a shift away from design principles developed from the store theater. The year 1916 saw the first book on motion picture theater architecture, Theatres and Motion Picture Houses by Arthur Meloy. In 1917, a second appeared, Modern Theatre Construction, by Edward Bernard Kinsila, who had begun a column the previous year under the same name in Moving Picture World, which claimed, “Mr. Kinsila has established a considerable reputation as a builder of theaters.”27

As the example of Kinsila demonstrates, it was not just architecture journals that had begun to recognize movie theater architects. In 1910, Moving Picture World inaugurated a column by John M. Bradlet, “The Construction and Conduct of the Theater” (subsequently known as “Construction Decorations”), which dealt with the problems facing movie theater design and construction.28 In 1913, Bradlet moved over to Motion Picture News, where he wrote the “Motion Picture Theatre Construction Department” for the next year.29 He was succeeded by Nathan Myers, “the well-known architect and specialist in motion picture theatre construction,” a description significant for simply recognizing the movie theater as an architectural specialty.30 In announcing his appointment and the beginning of a new column, “Architecture and Construction,” the News noted, “There is scarcely a town of any consequence throughout the country but already has, or is expecting, the building of at least one pretentious theatre devoted exclusively to motion pictures.”31 In 1916, latecomer Exhibitors Herald, which had only begun publication in 1915, inaugurated the column, “Theater Planning and Building,” whose author was listed as “W. T. Braun, Architect.”32 Announcing the architectural bona fides for their writers established respectability for this new architectural form to reflect the respectability of a new dramatic art. Respectability was a crucial issue because the store theaters in their earliest incarnations frequently had a disreputable taint that was often associated with class which, in turn, was a consequence of its architecture. But by the teens store theaters appeared in the pages of major architectural journals alongside extended photo-essays on the manses of the very wealthy.

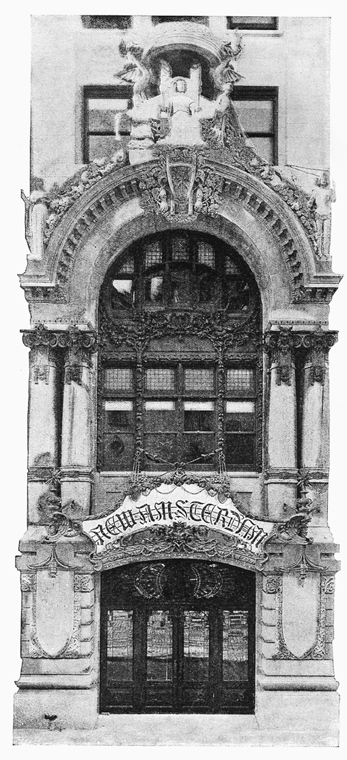

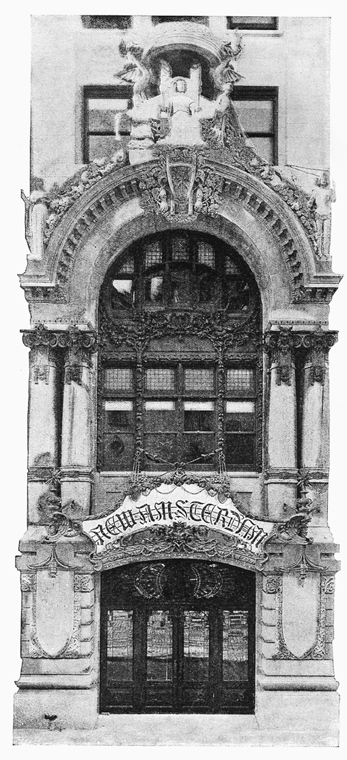

Much of the early writing on store theaters that appeared in exhibition journals tended to focus on façades, and this is a tradition that continues today in contemporary commentary on old movie theaters.33 While photos of interiors are rare, one of the most frequently reprinted images of a store theater from this period is the spectacular front of Milwaukee’s Butterfly Theater with the wings of its large goddess butterfly soaring above the third floor of the façade. In her study of the sources of early movie theater architecture, Charlotte Herzog has stated flatly, “The front of the nickelodeon was its most important part.”34 This, however, is not what made the store theater unique: even as it might have moved toward something more garish with façades covered by an excess of electric lights—and exhibition journals frequently boasted of the number of bulbs—its treatment of the exterior actually served to ally the store theater with straight dramatic theaters of the time: the concentration on the façade was an important issue for both because both often had a small urban footprint. Theater historian Marvin Carlson has noted commercial theaters in Paris, London, and New York had façades integrated into a streetscape, often as narrow as a storefront, that opened onto a passageway leading to an auditorium placed behind neighboring buildings.35 This was particularly true of legitimate theaters built in the decade or so after the arrival of the store theater along 42nd Street in New York.36 While the width of its auditorium in the store theater was no greater than that of the façade, the façades often followed a pattern Carlson notes for legitimate theaters, a pattern that could “identify the building possessing them, with reasonable certainty, as a theater…. The façade is normally divided into three horizontal units, the lowest containing entrances…the second containing the most impressive architectural elaboration…and the third offering much more modest fenestration, often topped by a pediment or other roofed elements” (Carlson, 118; see fig. 2.1).37 While never as garish as some store theaters, the entrances of legitimate theaters could be quite eye-catching in spite of their small size, relying on awnings, vertical stanchions, and illuminated signs to stand out from their streetscape.

Within a few years, the exuberant façades of the store theaters began to get disapproving notices within the trade press and more concern was directed to interiors: for example, F. H. Richardson wrote, “Too many owners, in erecting and finishing their fronts, seem to have in mind only something flashy to catch the eye, rather than something dignified and beautiful.”38 It was in the interior that a distinctive architectural form emerged since the image, granted an architectural dimension, became the defining spatial element. That the image was the key element in a theater’s architecture is evident in repeated assertions that the motion picture image could triumph over the stage by taking the whole world for its setting. The store theater lacked the defining element of live theater, a stage, but it offered something better in its stead. As a trade writer noted in 1908, “The picture parlor of to-day is nothing more than a small theater, where, instead of the elaborate and costly stage settings that the big theater had to pay for before the advent of the motion pictures, we have it all on the film; and we can go further than the setting of a drama or comedy on the stage and bring in nature’s own setting and background.”39 As Charles Frohman predicted at the Vitascope premiere, the crucial achievement of motion pictures in the context of contemporary drama lay in what it did for settings. The point was echoed after the establishment of the feature film by playwright and subsequent film director William DeMille in 1918, who accurately saw an inverse influence on the theatrical set design: “in the setting and the treatment the theater will become more suggestive and less imitative. The necessity for physical realism is going to disappear from the theater because that function will be taken care of in a better way by the photoplay.”40

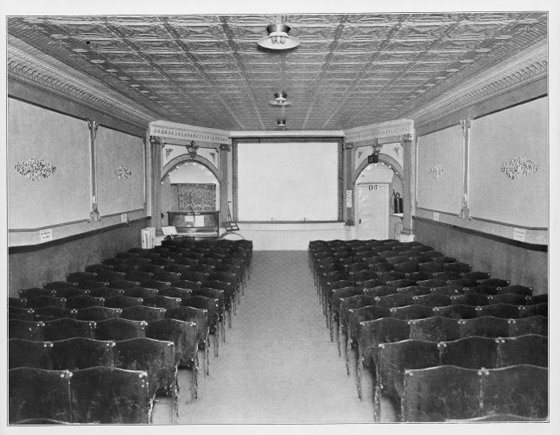

The plentitude of the film image, its seeming ability for contemporary observers to go beyond anything live theater could offer, seemed to dictate a simplicity in the rest of the auditorium, a simplicity that eventually would be rejected by the movie palaces that supplanted the store theater. But in the store theater, to paraphrase Roxy, all elements of the architecture had to work toward the screen. How did store theater architecture do this? Discussion of the store theater interior in trade and architectural journals focused repeatedly on a number of interconnected issues: the actual shape of theater; building code restrictions; seating; lighting; ventilation; location and handling of the projector; and framing, location, and size of the screen. In all these aspects, the store theaters offered at least some departures from previous theatrical forms, departures that reflect both external demands and demands of moving image presentation. By far, the greatest departure was a radical alteration of theatrical space, a rejection of spatial hierarchy that was a key feature of virtually all previous theater architecture. Along with concerns of how best to show a moving picture image, it was this disavowal of spatial distinction that drove much of the discussion. The image defined the space around it, not the composition of the audience, which could be diverse or homogeneous.

THE SPACE OF THE IMAGE

A long and narrow auditorium [is] the best disposition to insure a good projection.

—The Motion Picture News (1913)41

About ninety per cent of the small motion picture theatres to-day are long and narrow.

—The Motion Picture News (1914)42

Because of the desirability of presenting as nearly a direct view of pictures as possible to the audience to avoid distortion, motion picture theaters are often built long and narrow.

—Moving Picture World (1915)43

All art operates with some external constraints, but this is possibly more evident with architecture than any other art form, since architecture must always deal with an obvious set of external constraints: available space, preexisting aspects of the chosen site, available building materials, demands of designated function, municipal building codes, and so on. The earliest store theaters did in fact have fairly pronounced limitations: many beginning as Kinetoscope parlors simply sought to add some space for projection or, ultimately, transform the arcade space into a theater space. Conventions on how to handle interiors established themselves fairly quickly in part because they had to operate within realistic constraints. These were never quite as rigid as initial attempts to convert an existing arcade, but there were a number of external factors that encouraged the long and narrow shape typical of the store theater era.

As the name suggests, the store theater had fairly severe space limitations placed on it—the space of a store within an urban block, generally a narrow frontage of 25 to 30 feet extending back 50 to 100 feet.44 Even if a wider lot were economically practicable, which was the case for larger theaters that were more common outside of the big Eastern cities, building codes would encourage the long and narrow shape by requiring alleyways along the width of the theater for quick and easy egress in case of fire.45 Exits in the front of the auditorium that led into alleys would also place limits on how the screen was situated, presenting an architecturally defined frame that could take up half the front of the auditorium. While mandated by fire codes, this tripartite division of the front of the theater was one area where the store theaters did have an influence on subsequent movie palace design: locating the screen between two architecturally defined elements set a pattern for situating the screen that would pervade exhibition throughout the silent era (fig. 2.2).46

As early as 1910, John M. Bradlet, author of an architectural column for Moving Picture World, thought theaters were getting too long. The shapes could indeed reach extreme proportions. Certainly, one can understand this complaint with a theater like one in New Haven, Connecticut, which arrived at its 766-seat capacity by extending a 27-foot width along a 200-foot depth.47 Bradlet recommended a balcony to improve the shape of the theater: “The absence of a gallery forces the builder to make the most of the floor space to accommodate enough seats. In the majority of the narrow houses we find not over 12 chairs in a row and, to seat 300 persons, we must have 25 rows, or a hall not less than 100 feet long. If a gallery was provided to seat 75 or 100 persons, we would gain a space in the hall of about 25 feet.”48 Still, even the occasional addition of a balcony did not necessarily change the preference for long and narrow: for example, a theater built in 1912 in Wichita, Kansas, seating 900, with 250 in the balcony, was 25 feet wide and 140 feet long.49

External circumstances might have promoted the long and narrow shape, but, once established, it was also seen as the most suitable for the projected image, as indicated by the progression in quotations at the head of this section from simple observation to endorsement. The long, narrow theater represented a functional style born of necessity, not theory. But, however arrived at, the form was subsequently seen as the most functional for the motion picture image. In 1910, when he recommended shortening the length of theaters, Bradlet stated that films look better in small towns than in big cities because auditoria were not as narrow nor as deep. By 1913, he reversed himself and stated a preference for the long over the wide theater.50 The most likely reason for his change of mind was the increased prominence of motion pictures in older vaudeville theaters, which were wide, and the advent of small-time vaudeville in similarly sized theaters—in 1910, for example, Keith and Proctor “turned six of their seven theaters in the Manhattan district into moving picture theaters.”51 With conventional theatrical spaces being utilized more and more for motion picture exhibition, the optical problems of wide theaters became increasingly recognized in a way they were not when film was exhibited in horseshoe theaters.

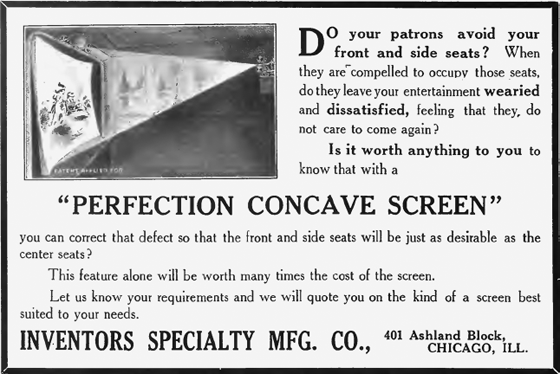

In 1910, when Bradlet was advocating wider auditoriums, another writer for Moving Picture World summed up the problems of projection in large theaters: “I do not consider the arrangement of many of the larger theaters the best possible for moving picture projection. The relation of the projecting machine to the screen is not by any means ideal, and the pictures show it. There are too many unfavorable seats: too many near the screen, and too many at the sides, where the picture is viewed at an angle, causing foreshortening.”52 A 1914 Motion Picture News article on screens noted a need for a special screen to disperse light in such theaters: “otherwise the picture could hardly be seen from all seats, owing to the horse-shoe shape of the old theatres.” But “if your theatre is long and narrow, all screens will suit your purpose.”53 The problem of wider theaters was acknowledged by the development of a curved screen that claimed to solve the problem. An advertisement for the “Perfection Concave Screen” asked the questions, “Do your patrons avoid your front and side seats? When they are compelled to occupy those seats, do they leave your entertainment wearied and dissatisfied, feeling that they do not care to come again? Is it worth anything to you to know that with a ‘PERFECTION CONCAVE SCREEN’ you can correct that defect so that the front and side seats will be just as desirable as the center seats?” (fig. 2.3).54 This ad copy treats all the answers as self-evident, suggesting that problems of distortion were common knowledge among film practitioners. Quoted testimonial from a Manhattan exhibitor in a subsequent advertisement suggests audiences were perfectly aware that some seats were better than others: “The pictures are now equally distinct and the characters and outlines in exact proportion as viewed from all parts of my theatre. In addition, the side seats in the theatre, which formerly were shunned by patrons because of the blurred appearance of the characters, are occupied with satisfaction.”55 However successful this screen might have been, it was the space of the auditorium that determined the need for it. On the other hand, all the submitted entries in the 1914 Brickbuilder design competition showed a long and narrow auditorium. This was clearly understood as the optimal shape before the advent of the movie palace.

The actual size of the image, one of the raging concerns of the store theater period, was also a factor in how well the projected image appeared in the narrow long house. Initially, there was a very strong sense of what size the screen should be. An early issue of Moving Picture World (1907) reported the following conversation at a motion picture supply house: “ ‘What size picture do you want at a distance of sixty feet?’ ‘Life size,’ ” with “life size” specified as 13 feet wide.56 “Life size” is a phrase that turns up repeatedly in the trade press as a recommendation for what the image should look like, and the recommended screens generally range between 11 and 13 feet. In 1910, a Moving Picture World writer stated categorically, “In most pictures, the proportions of the actors are such that they would be very nearly life-size on a screen about 9 x 12 feet” (C.Y., 744). How could the writer be sure that a 12-foot image would be life-size? This particular problem provides the strongest correlation between projection and production practice because the expectation that a constant screen size would produce a “life size” image could only happen if there was a constant camera distance in production.

There had in fact been a common distance in American film established by the “twelve-foot line,” which generally placed the camera twelve feet away from the human subject. But it was precisely in the store period that this began to change, eventually reestablishing itself as the “nine-foot line” somewhere around 1909–1910.57 This did not happen without contestation as there were complaints about the camera being too close in 1909. By 1911, an editorial in Moving Picture World, complaining about “unnecessarily large and, therefore, grotesque proportions,” issued a “fundamental rule…no figure should appear larger than life-size to the eye.”58 Although the World was specifically talking about production practice (“Too Near the Camera”), they were actually addressing a problem that had begun to appear in both production and exhibition.

Strikingly the terms of the arguments against closer camera distances are explicitly echoed in arguments against larger screens that had begun to appear in the larger—and longer—houses. So, for example, the writer who defined a 9-ft. x 12-ft. screen as life size in 1910 complained about the 14-ft. x 18-ft. screen at the Orpheum Theater in Chicago as “far too large” by noting: “the actors appear like giants, which is unnatural,” adding, “Not all films are of such photographic quality as to bear this extreme magnification,” a claim not without warrant (C.Y., 744). A Moving Picture World editorial from the previous year complained of actors too close to the camera in almost identical terms: “The consequence was that the people in the theater had the idea that the film showed a story that was being enacted, or had been enacted, rather, by a race of giants or giantesses…natural size [is] more agreeable to the audience.”59 For a contemporary viewer, then, similar results could be accomplished and similar complaints generated on either the production or the exhibition end: unnatural giants.

Writing in 1911, John M. Bradlet made this connection between production and exhibition explicit in an article that segued from a complaint about screen size to a complaint about close camera distances. Bradlet criticizes the image on the larger screen for not showing things in “their natural sizes.” When he advises an exhibitor against a large screen, the exhibitor replies, “The public demands a large picture.” Rather than accept this, Bradlet assumes it is the complaint of a few filmgoers with bad eyesight and advises them to use opera glasses! This suggests the preference for life-size images is not grounded in a desire to reproduce reality in general, but rather a specific desire that the screen should reproduce the experience offered by live theater. If you feel the camera distance has limited your ability to see, then use the same solution you would use for live theater! Finally, he makes a connection between parallel developments in exhibition and production: “Well, the exhibitor is not the only one to blame, as the manufacturer is also guilty. There is nothing more absurd on the part of a manufacturer, nothing which destroys the art and beauty of a scene more than showing us greatly enlarged faces of the leading actors.” By current standards, we would not consider these figures “greatly enlarged” since Bradlet further specifies “these enlarged figures, with the head touching the very upper part of the frame, and the feet missing.”60 Keeping in mind the fact that the screen at the 140-foot long theater in Kansas City noted above was 15 ft. 4 in. x 11 ft. 6 in., I would argue that the change in figure size Bradlet ascribed to the manufacturer in this description is not at all unlike what would be experienced by enlarging from a 12-foot wide screen to 15 feet in a long theater. If 13 feet wide was considered life-size at a distance of 60 feet in 1907, how would it subsequently appear at 100 or 140 or 200 feet?61

The increasingly long viewing distances of the larger theaters inevitably conditioned a more flexible understanding of screen sizes. F. H. Richardson wrote a handbook for motion picture theater operators in 1910, subsequently the standard projection reference book.62 One of the most astute observers of motion picture theaters throughout the teens, he proposed a more relativistic approach to screen size in 1909, even while giving voice to the standard preference for a “life-size” appearance: “The curtain [screen] should be of size to accommodate a picture in which the figures will be at least life size. Nine by twelve will do nicely for a small house, but for a house of ample dimensions the picture should be at least fifteen feet in width. It must be remembered, however, that every foot added to the picture size adds enormously to the necessary light intensity to produce equal brilliancy.”63 Richardson would always remain concerned about the loss of image quality with a larger screen (“Better have a good small picture than a bum large one”), but in 1910 he could expand his recommendations up to 18 or 20 feet, albeit preferring 18 feet, for a theater 120 feet deep.64 If “life-size” remained a continuing concern in this period, and larger theaters made the 12-foot wide image geared to the 12-foot line in production actually appear less than life-size, then it is reasonable to assume that the larger screens necessitated by the longer theaters were paralleled by the closer camera distances that became more common in the same period. The long, narrow house in effect became one condition of creation for film producers.65

ANTI-HIERARCHY ARCHITECTURE

Now for the first time in history a new art is being born that is more democratic than the drama—and the drama always has been the fundamental democrat of the arts.

Placing seats in front of a screen would seem like a fairly simple matter since the seats all need to be arranged in relation to a fixed object, ranging anywhere from about 12 to 15 feet across. But the simplicity itself contained a problem. Live theater was presented on stages that averaged between 30 and 40 feet at their proscenium opening; further, the stage existed in a three-dimensional space. These two facts made live theater effectively more forgiving since the broader expanse and the actual depth multiplied the number of vantage points for any audience member: if any individual was not able to see the whole stage, they would nonetheless be able to see a significant part of it. This opposition was understood early on as the following from The Brickbuilder in 1914 indicates:

People will attend grand opera or a performance given by a great actor and be satisfied with seats from which they can see only a portion of the stage so long as they can hear the voices or see part of the acting. In a picture theatre the interest is focused on a small part of the stage as compared to the area covered by the actors in a legitimate production. It is therefore vitally essential that the sight lines be so arranged that each person may have a good view of the whole screen.67

I want to linger over this point now because it will play an important role in a theoretical understanding of movie theater architecture that emerged in the 1930s. Clearly, the long, narrow hall, ideal for the film image, would have been a disastrous shape for live theater. But even with this shape, perfect visibility of that narrow space of the screen placed restrictions on how the seats were to be arranged. Furthermore, these restrictions competed with economic demands as well as the dictates of emerging building codes, and these were concerns that carried over into the movie palaces as well. For example, staggered seating, so that each seat was not directly behind another, is the simplest way of improving visibility for each movie spectator. Yet it actually took quite a while for staggered seating to become a norm because it generally meant a loss of seats every other row to carry it out. Optimal seating arrangements often lost out to exhibitor demands for higher seating capacities, most especially in the period under consideration as the store theaters grew larger and larger until they were finally supplanted by the palaces. The competing interests could be most clearly seen in how aisles were situated. In 1911, John M. Bradlet complained that architects were following the pattern of the opera house by placing an aisle directly in the middle of the auditorium: “If these architects were students of motion pictures, they would know that the best seats are the ones directly in front of the screen, while the picture, viewed from the side seats, always appears more or less distorted.”68 But the central aisle need not be attributed to the model of the opera house. It’s often hard to determine exactly what the arrangement in the earliest store theaters were like because there are no actual architectural plans and photographs of interiors are rare. There are isolated early photographs that do show seemingly wall-to-wall people, indicating at best very narrow aisles on the ends of each row. But the disadvantageously located central aisle seems more common, and for the good reason that one aisle enables more seats per row than two aisles on the end. There were variations in building codes throughout the country, but there was enough similarity for Motion Picture News to publish general rules for seating in 1914: “Chairs between two aisles should not number more than thirteen, and between an aisle and the wall not more than seven.”69 A central aisle, then, could gain one seat per row. Maximizing the number of seats was the same reason for center aisles in the small multiplexes built inside shopping malls in the 1970s and 1980s, once again removing the best seats for film viewing.

Another factor that had an economic dimension to it was the floor slope, but here theory seems to have won out over expense. The earliest store theaters likely had flat floors, as low-cost conversions would continue to have been a determining factor. A 1910 article on the problem of seeing over the oversized hats women preferred in this period recommended that women could keep their hats on, “if all moving picture theaters had their floors constructed on a slant.”70 By the teens, a slope seems to have become a mandatory feature: all of the illustrated entries in the Brickbuilder competition show sloped floors in their longitudinal sections.71 The sloped floor was hardly unique to the store theaters, however, since it is commonplace in nineteenth-century theaters, but the historical precedent likely helped it become even more of an imperative when coupled with the distinctive sighting requirements of motion pictures. Especially in the absence of staggered seating, the slope helped individuate each viewer’s perspective.

Much as it took over the sloped floor, the sloping actually pointed to something very different from live theater, although not without precedent: as every seat putatively provided a good view of the screen, there was a widely held belief that the motion picture theater democratized theatrical spectatorship. There was some limited concern with making spectatorship more democratic in late-nineteenth-century theater, but it was really with the store theater that the democratic nature of viewing became an issue, as indicated by the William DeMille quote at the head of this section. Following his complaint about the center aisle in the store theaters, Bradlet attacked architects for one other area of ignorance: “Some architects, not knowing the requirements of motion pictures, and believing that every theater should have side boxes, near the stage, have provided many such boxes in moving picture theaters, and the managers, who had an idea that they could increase their receipts by having reserved seats in the boxes, have been badly deceived” (Bradlet, Jan. 21, 1911). Even Adler and Sullivan had to give in to a demand for side boxes at the Auditorium Theatre. But when side boxes did appear in the store theaters, their poor vantage points ultimately transformed them, creating new functions such as a screen “flanked by two private boxes, reserved for the use of the lecturer and singer” (who were intended to accompany the film showings in a 900-seat theater in Milwaukee, billed as “High Class in Every Detail”) or rendering them “purely ornamental” (a 600-seat theater in Detroit trying to appear “pretentious,” generally a favorable adjective for theater architecture in this period).72 Omitting, removing, or transforming the side boxes effectively rid these spaces of the most overtly antidemocratic aspect of seating in live theaters.

There has been much debate in film studies over the composition of the store theater’s audience, whether it was primarily working class, working class in just major urban centers (with guilty-pleasure visits paid by middle- and upper-class slummers), or a mix of all classes.73 Indisputable, however, is the fact that the very low cost brought in people who either did not often go to the theater or people who at most could afford the cheapest seats in the upper balcony of live theaters. Calling moving pictures “a sort of people’s forum,” Moving Picture World writer Stephen Bush claimed they had abolished price and class distinctions along with the old belief that the poor must be segregated: “Much of the hostility against the motion picture abroad is due to its enlightening and leveling influence.”74 Theatrical producer Daniel Frohman, Charles’s brother, attributed the success of movies to a combination of price, product, and seating:

There is much to be said for an amusement which a poor man can have for ten cents. The galleries [i.e., the second balcony] of the regular theatre, that portion of the house from which a large part of the profit is derived, are being emptied, not because of the price of the seats, but because the average theatre-goer has always objected to paying a disproportionate price for a poor seat and poor play together, when for ten or twenty-five cents he could sit down stairs in a moving picture house and get something in which he may be really interested.75

For both Bush and Frohman, seating was the crucial issue: if the poor could now sit where the rich normally sit, the rich would have to sit next to the poor to enjoy the spectacle. In effect, store theater architecture in doing away with spatial segregation in seating did away with class distinctions that had been inscribed in theater architecture for centuries.

This would change somewhat with the reascension of the vaudeville theater as a venue and the building of the palaces, but the belief in the democratic nature of movie-viewing that began with the store theater became a factor in palace architecture as well because of the way in which spectators related to film spectacle. If early film theory was centrally concerned with locating the differences between film and theater, I would claim it is precisely—and paradoxically—because most contemporary viewers saw a continuity between the two. That continuity made film practitioners equally concerned with difference: one was close enough to the other that differences had to impact on practice, such as the design of the theater, as we’ve seen. A technical writer for Exhibitors Herald noted a difference in 1916 that was crucial to contemporary understanding of motion pictures as the more democratic of arts, “One is viewed on a flat screen which viewed from all positions is always the same—a picture; the other is composed of people on an actual stage, with a perspective, which changes to every seat. People in various parts of the house see it differently because of the angle of vision.”76 This difference in viewing experience made movies more democratic because movies effectively had the power to override the inevitable hierarchization of space in theater architecture. This belief was in fact a myth, as would be acknowledged by theater architecture several decades later, but it was sufficiently accepted as truth at the time to guide the development of motion picture theater design.

Further, that this was a distinctly American view of movies can be seen by a 1910 report on “A London Moving Picture House De Luxe” in Moving Picture World. Although it was fairly small, it nonetheless had differential pricing, “the balcony being reserved for the highest-priced seats…. The front seats are priced at 3d., the back seats 6d., and those in the balcony are 1s.”77 The fact that even the larger theaters that grew out of the store theaters in the United States continued to be called nickel theaters made clear the admission price was the great leveler. While a 1910 Moving Picture World editorial recommended that “it is perfectly possible to conduct a house on the differential price system,” and the presence of vaudeville in the bigger theaters could lead to some pricing differences, in general American movie theaters tended to shy away from this.78 Further, outside of an important regional exception in the South, American theaters never attempted an architectural distinction found in the London movie theater and common to European theaters and opera houses, the creation of lounges segregated by seating area: “one being reserved for threepenny seat-holders, and the other two for sixpenny and shilling patrons” (“A London Moving Picture House”).

ARCHITECTURE AND ANXIETY: ODOR, LIGHT, FIRE

The democratic nickel theater had its downside for some observers in the range of patrons it could attract. Much like the repeated calls for higher ticket prices as a way of attracting a higher class of patrons, addressing the disreputable status of the early store theaters, making these undifferentiated spaces amenable to all classes, animated the chief architectural concerns repeatedly addressed in trade journals: ventilation, lighting, and physical safety. The spatial separation by class of the traditional theater could operate as a form of social control. So, for example, the second balconies could be home to the lower classes as well as prostitutes looking for customers. The decampment of these customers for the store theater made it a new business address for prostitutes, since indecorous activities could and did take place in the dark. In this context, lighting instead of spatial separation could serve as a form of social control, which is how it often ended up allied with ventilation. Thus, a 1909 Moving Picture World article moved directly from a discussion of lighting to the importance of ushers “in excluding undesirable visitors, the better for the reputation of the house.” And this led directly to the following: “Too much attention cannot be given to the cleanliness of the house; to its proper ventilation, and, then to the preservation of quiet and order amongst the audiences.”79 Light, cleanliness, ventilation, order—for contemporary observers who sought to improve the reputation of store theaters, these were interconnected concerns necessitated by the democratic audiences: the theaters had to be kept safe from their audiences of unwashed masses, whose odors and indecorous behavior necessitated both the elevated light levels as well as the circulation of fresh air.

The store theaters seemed to have been a magnet for concerns about dirt, whether dirty air or actual dirt dragged in from the street by presumably dirty patrons. A theater in 1907 was praised for its “ventilating system [which could] draw out the foul air and replace it with sterilized fresh air.”80 Another theater in 1910 was cited not only for its good ventilation, but for having “an obliging usher who meandered up and down the aisles spraying [the audience] with some sweet scented liquid,” a not uncommon practice.81 Smell signaled dirt, and dirt was dangerous: “The great amount of disinfectants sold yearly to moving picture theaters shows the unsanitary conditions of the present floors, absorbing and retaining all the filth carried from the street.”82 And dirt was clearly connected to class: in an article advocating raising ticket prices beyond a nickel, Moving Picture World columnist W. Stephen Bush boasted that theaters with high prices “are making far more money by charging more and are in addition blessed with a better and cleaner patronage.”83 In this formulation, “better” meant people who washed.

From the perspective of a century later, the strangest aspect of the discourse on the new dedicated movie theaters is the repeated insistence that light levels should be kept bright enough during the show to read a newspaper:

As much light as may be furnished without interference with the picture on the screen should be supplied at all times, as an audience is much more affected by panic when in almost total darkness. (1908)84

As we took our seats we could see to read a newspaper that we carried. The effect of this unnecessary volume of light was to degrade the brilliancy of the picture on the screen, which appeared to the audience to have somewhat of a misty look. (1909)85

The house [the Auditorium Theater, Dayton] is well lighted, in fact you can read a paper in almost any part of the house. (1910)86

The lighting of the [Coliseum Theater, Seattle] is very good; a newspaper can easily be read at any time during the show. (1911)87

The [Orpheum Theater, St. Joseph] is so lighted that one can read a newspaper in any part of the house while the picture is being shown. (1912)88

But why would you want to read a newspaper while watching a movie? An Englishman visiting a New York movie theater for the first time in 1909 did wryly report a counterpoint to the tension he felt viewing a melodrama, “Then the clouds began to gather [i.e., on-screen], the man on my right opens a book and begins to read.”89 American lighting practices were distinctive, as European theaters tended to be dark, something of a flaw from an American perspective.90 A 1914 Motion Picture News article entitled “America First in Picture Theatres,” for example, cited Samuel Rothapfel’s disapproving comment, “All the European houses are pitch dark while the pictures are being shown.”91 Why the difference? The lighted theater certainly addressed concerns about safety: nitrate film was explosive, and there had been dangerous fires in store theaters. But the fact the European theaters could function safely in the dark suggests other concerns as well.92

There was very likely a correlation between light levels and the practice of continuous performance through a very long day. The modular nature of the standard store theater’s program, comprising a number of short films, ensured that audiences could arrive at any time and take any seats available. The resultant constant traffic would require light levels sufficient for people to find their way to empty seats. Much as the modular nature of the store theater’s program was a direct imitation of vaudeville, the continuous performance practice likely derived from vaudeville, where it had been originated by B. F. Keith. And it is likely that vaudeville did not use a fully darkened auditorium either: in 1910, Samuel Rothapfel was hired by the Keith and Proctor chain to improve the lighting in their theaters so that the screen image could be sharp while the auditoria remained light.93 Light in vaudeville theaters was directly connected to reading, albeit not newspapers: playbills identified individual acts for viewers. Furthermore, the kind of performance offered by the vaudeville theater made light levels in the auditorium of lesser importance than they would be in straight dramatic theaters, where the advent of the fourth-wall aesthetic was in part dependent upon the possibility of a darkened auditorium. Even as the movies had cast its lot with fourth-wall aesthetics, the theaters embraced a vaudeville aesthetic in their lighting procedures because they embraced vaudeville programming.

Although it began with the store theaters, the call for lighted houses was not limited to small theaters with disreputable clientele; it continued even as motion picture theaters grew larger and the class range of the audience expanded. As late as 1914, when Vitagraph took over a legitimate theater and changed its name to the Vitagraph Theatre in order to promote its product, the theater was praised because “a complete lighting system, calculated to make it possible for one to read a newspaper at any time, has been installed.”94 The fact that this was still an issue might reflect continuing concerns about safety, but by this point the booth was fully separated from the audience. On the other hand, this was also in response to city ordinances, which were likely prompted by concerns about social control. In 1910, “All of the Chicago theaters are lighted houses, being required by city ordinance.”95 And in New York City in 1911, “recent ordinances compell[ed] the owners of theaters to illuminate their theaters at all times.”96

All this had to have an impact on theater design. The mutual exclusive aims of image visibility and an illuminated house could be accomplished in two ways: by forms of illumination that would keep the area of light relatively restricted; and by manipulating how the image was situated. A dose of sensibleness was also needed, which was finally provided by F. H. Richardson in 1912: “That considerable light is desirable in a theater auditorium, or other place where large numbers of people assemble, no sane man would deny,” Richardson conceded. But when he asked, how much light, he answered somewhat differently from his contemporaries: “Just sufficient to enable one, after being seated long enough to become accustomed to the semi-gloom, to see clearly objects in one’s immediate vicinity and to dimly discern objects all over the house. It is not necessary to be able to read a newspaper. One doesn’t go to a theater to read papers while the show is on.” Finally, although the darkened theater was only a phenomenon of the late nineteenth century, Richardson suggested a similarity between the two theatrical forms by claiming, whether it was stage or screen, “Too much light detracts from the interest of the show.”97 Richardson’s prescription for “semi-gloom” pretty much carried the day in subsequent theater design, whether store theater or palace.

One solution to the illumination problem in the store theater did provide a lasting contribution to motion picture theater design: downlighting. The earliest example I have found of this is in the 1910 description of a Chicago theater, “in which the lamps, located on the ceiling, are enclosed in deep cone shades, which confine the light to the place where it is needed, and protect the screen at the same time.”98 Several months later, in his regular column Richardson drew a sketch of a similar method.99 Downlighting would become a standard fixture in small theaters, where the ceiling is close enough to keep the circle of light fairly contained, or under the balcony overhang in larger theaters. But downlighting arrived in a period when motion picture theaters began to take on gargantuan proportions. In these very large spaces, other solutions had to be found, some involving light and some involving the actual situation of the screen. How the screen was situated in the auditorium directly related to anxiety over light levels because of the potential for degrading the screen image. Following the fourth-wall aesthetics of naturalistic theater, which sought to make the space of the setting distinct from that of the theater, store theaters evolved a number of approaches to setting the space of the film image, seemingly so different from our space, off from the rest of the theater.100 Because store theaters either didn’t have a stage or only had a shallow one, they borrowed the picture frame from vaudeville theaters to create a de facto proscenium: the frame was either made part of the screen—some manufacturers would in fact ship the screen enclosed by a gilt frame—or made an integral element of the architecture surrounding the screen. In 1909, F. H. Richardson acknowledged both approaches with his recommendation for situating the “curtain,” i.e. the screen: “A neat, heavy moulding around the curtain adds very much to the effect, but better yet is a ‘flare’ from eighteen inches to two feet in depth such as one sees in the proscenium arch of a theater.”101

But the lighted house of the store theaters presented a problem not seen in live-performance theater where the stage could be illuminated at a much higher level than the auditorium: the gilt frame around the screen could pick up the light from the theater, sending distracting reflections back to the audience, or reflecting light onto the image itself. To lessen the effect of reflections, store theaters began utilizing a dead black border, really the first instance of black masking, which could be achieved either by painting directly on the screen or by layering black cloth around it. As an added bonus, contemporaries thought the black border could heighten the apparent brightness of the image by creating a sharp contrast. In the same column in which he recommended a frame for the image, Richardson also recommended a black surround: “It will be found that much brilliancy will be added to the picture by painting all the curtain except the space actually occupied by the picture a dead black.” Another commentator thought a “black cloth border…enhanced the value of the picture by giving it perspective or greater ‘depth.’ ”102 There was some experimentation to heighten the brilliance of the picture by contrast in ways that might seem odd to us now, such as having colored lights play around the image103 or another for black masking which would then be surrounded by an illuminated colored-glass frame to achieve a greater sense of depth and relief in the image.104 Since its success was founded in a stark contrast between dark and light, the use of black masking, like the illuminated house itself, effectively called for a light film image with a relatively flat lighting style. A key reason for this is that the image itself was not very bright. The black masking might have helped boost the visibility of an image in a lighted theater, but it also offered a way of compensating for the relatively low projection-light levels allowed in a number of U.S. municipalities. Where there were reports of carbon arcs running in Australia at 90–100 amps and in England at 80–90 amps, New York City law set limits at 25 amps.105

To compensate for such low illumination levels, screens were developed that could take advantage of the store theater’s narrow widths by reflecting light back at the same angle it hit the screen, rather than a more diffuse dispersal of light needed for wide auditoriums. Ads for such highly reflective screens appeared with some frequency in trade journals from 1909 on and always made claims about their properties in relation to the illumination in the theater, thus connecting screen illumination itself to a concern for social control. A 1909 promotional article for the “Mirror Screen” noted, “it is not easily affected by other light, therefore it allows more light to be had in the theater.”106 And an advertisement for a metallic screen coating the same year boasted, “After using it on your curtain your house can be light enough to read the finest print and you’ll have a better picture than you had before with your house in pitch darkness. No more reason for your patrons to be stumbling over themselves in the inky darkness…. Your house can be light as day; You can open your doors and windows wide and allow free ventilation and have no fear of a dimmed picture. Outside light has no effect.”107 In effect, the ad promised that light, fresh air, and a brilliant image—the very things needed to keep the theater safe and attract all kinds of patrons—could be had with the right screen.

If lighting and ventilation were in part issues of public safety, the location of the projector would seem to be entirely that, and entirely beyond contestation. Noting that motion picture film will ignite in about three seconds if it stops moving, a 1908 article considered it “most important” that “the picture machine be enclosed in a thoroughly fireproof, and as far as possible smoke proof, operating room.”108 While there was continued debate into the 1910s about whether or not to have an open booth in vaudeville theaters, in the store theater there was never any reason to show the operator or the apparatus. Typical of the understanding of theater architecture in the period, concerns with illumination could lead to concerns about fire: “the laws of some states require that picture theaters be illuminated every 15 minutes during the show. The reels are highly inflammable, and panics occasioned by their conflagration have more than once caused grave loss of life.”109 Concealed projection booths seem to be an early fixture in architectural design, perhaps as much for dampening the sound of the projector as for concerns about fire safety. Given this necessity, an architectural form very quickly emerged in the store theater that was a deft and economical use of space: the booth was centrally located over the entryway, generally with entrances into the auditorium on either side of it. It might also be located on stilts over seats at the back of the auditorium, although this seems primarily a design of the earliest store theaters that got dropped from later, more luxuriously appointed interiors. In either way, space taken away from seating was minimized.

More rigorous building and fire codes in the teens did finally demand a separate, and fireproof, “operating room,” as it was generally called, as a matter of public safety. But the common booth of the room at the back of the theater also created a problem by placing the source of fire right in the path of exodus from the fire. There were some suggestions for reversing the auditorium, placing the screen near the entrances, but the more common solution was additional fire exits placed near the screen. The operating room remained a fixture chiefly at the back of the auditorium, aligning audience movement in toward the screen with its own trajectory.110 Given the concerns about panic, however, there was another possibility rarely explored in the United States. Jean-Jacques Meusy has noted it was not exceptional for Paris theaters to locate projectors behind a transparent screen, “the most famous being the Gaumont-Palace,” the largest and most luxurious theater in Paris devoted to motion pictures (Meusy, 84). For fear of audience panic in case of fire and smoke, rear-screen projection offered the best solution for keeping danger fully isolated from the audience, yet this was in fact an exceptional procedure in U.S. theaters.

In the case of the store theaters, either the lack of a stage or a limited stage might have been the reason for not using back projection, but ample stage area was offered by the vaudeville theaters, and even they eschewed rear-screen projection.111 Promoting an awareness of the projection booth was a kind of assurance of safety, a way of preventing the kinds of “panics” that a “conflagration” might cause. The apparatus might be partly concealed, but the activity of image-making, its separate points of origin and destination, were generally evident to U.S. audiences. As much as later theories of spectatorship can construct a naïve spectator absorbed by the image, the very structure of the theater essentially exposes how the image is created, with a beam of light emerging from a back wall until it strikes a surface in front. Compared to this kind of moving image-making, television technology is completely opaque: we simply have an image with no sense of how it arrived on its screen. The preferred manner of situating the moving picture image in the architectural space of American theaters followed from the earliest showings with the visible projectors: the nexus of anxieties in store theater architecture might have dictated the enclosed booth, but the technological production of the image was always made evident.

THE STORE THEATER IN THEATER HISTORY

By the middle of the teens, stories of store theaters becoming stores again began to appear.112 Increasingly, “large” and “pretentious” were adjectives attaching themselves to movie theaters: “There is scarcely a town of any consequence throughout the country but already has, or is expecting, the building of at least one pretentious theatre devoted exclusively to motion pictures.”113 With the rise of the feature film, the store theater ceased being economically viable, so that one architect could note in 1916: “very few of the remodeled store buildings still house moving picture exhibitions” (Braun, May 6, 1916, 23). They would soon disappear entirely from the urban landscape, existing primarily in memories of the “nickelodeon,” the name itself taking on a kind of quaintness. Does the store theater, then, have no lasting contribution to the architectural and theatrical forms that succeeded it?

As an architectural form the store theater could well have been a model for dedicated movie theaters that followed with the rise of the feature film. I would like to consider one example that suggests how the store theater might have evolved. The American Theatre opened in Salt Lake City in July 1913 and was billed as “America’s Biggest Picture Theatre” (fig. 2.4). It would be eclipsed within a year in size and with a very different design, but before then, Moving Picture News thought it worth noting that “it is hard to realize that the building is dedicated exclusively to the photoplay. Its capacity is nearly twice that of the majority of New York’s legitimate theatres.”114 Although the invocation of legitimate theaters is meant to advance the claims of this theater to quality, the design of the American grew more out of the store theater: it lacked a stage and it situated the screen within a gilt frame surrounded by black masking and a larger frame outside of that. This was a dedicated movie theater, with no live performance other than what accompanied the film showings: “The program is uniformly composed of five reels of pictures. Sometimes a five-reel feature will be the evening’s entertainment. At others, single reels, with a two or three-reel subject, will be offered.” The theater was also something of a departure in ignoring the demands for variety: a feature film could suffice as entertainment on occasion.

The actual size of the auditorium was 165 feet deep by 90 feet wide. The depth, then, approached the longest store theaters, but the American was nearly twice as wide. Still, the shape was substantially longer than wide, so that it could nicely accord with contemporary understanding of movie theater form. But in contrast to the one admission price at store theaters, the American offered a range of prices that implicitly acknowledged a limitation in the sight lines. Next to a small block of 300 seats in the orchestra, the second most expensive seats were in the 500-seat balcony, “a block of two hundred seats, on either side of the operating-room, and in a direct line with the screen.”115 This differential pricing, then, pointed to another departure from live theater by offering a different rationale for what determined a good seat. Essentially, seats that would fit within the then dominant long and narrow shape of the dedicated motion picture theater would fetch the highest price; the more seats departed from it, the lower the price. This way of looking at seats would not last long, however. While the motion picture did indeed triumph as a popular theatrical form, the American Theatre, nonetheless, proved to be more the last of its kind rather than a promise for the future. For all the big theaters that emerged in the United States following it, a full stage was called for and a different shape took hold.

This is not to say, however, that the store theater had no impact on later developments. There are two areas I need to address here. The first takes up an ongoing dialogue that film theaters were having with live theaters. If the format of the store theater drew on vaudeville, the kinds of work it presented nevertheless invoked dramatic theater, its limited size dictating playlets rather than full-length plays because of the need for constant turnover. It was precisely the connection to live drama that made contemporary writers see a democratic aspect in movie theaters. The extraordinary proliferation of store theaters in a fairly short time frame meant that dramatic narratives were suddenly available to everyone at low cost and under the same conditions: the store theater transformed theater by removing it from the theater. This new understanding is reflected in the observation from 1915 cited earlier that the “picture parlor of to-day is nothing more than a small theater.” Up to this point, I have looked at influence in one direction, from live theater to movie theater. But the sudden ubiquity of a theater of dramatic performances staged in the unlikely precinct of a store suggests the possibility of a reciprocal influence.

To my knowledge, histories of American theater rarely if ever acknowledge the store theater or the nickelodeon. But if we look at theater history from the perspective of motion picture theater history, then it has to seem more than coincidence that the first substantial challenge to the dominant commercial theater in the United States occurs in the context of store theater proliferation. The emergence of the Little Theater movement in 1912 reflects an understanding that theater did not require the elaborate physical resources of commercial theaters to provide compelling dramatic entertainment, an understanding that had to be conditioned by the success of the low-cost store theaters.116 If the movie store theaters chose unlikely spaces for conversion, the Little Theater movement distinguished itself by “mounting plays in what might now be called ‘alternative spaces.’ ”117 One of the best known, the Provincetown Players, for example, set its first theater in Massachusetts in a converted fish-storage facility on a wharf and subsequently opened a theater in New York City in a stable. The Little Theater movement also represented a challenge to the dominant realistic mode of commercial drama, and in this regard it effectively challenged what was becoming the dominant mode of filmed drama. But the influence does not end there; rather, it takes a cross-fertilizing route, returning once again to the film theater. The subsequent emergence of the motion picture art theater, which was specifically called the Little Film Theater movement, is the one place you can see a continuity from the store theater, although it came about in a circuitous manner, first taking a detour back into live theater. Commensurately, as the Little Theater movement in live theater often countered dominant naturalistic staging, the Little Film Theater movement opened up a space for motion pictures that went against the dominant realist aesthetic as well.

Where the simplified style of the art theater sought to give unimpeded access to the dramatic text, the little film theaters in the 1920s followed the store theaters in aiming for unimpeded access to the motion picture image and generally did so with the familiar long and narrow hall. The Film Guild Cinema was unusual in employing a modern architect for its experimental design, but the relatively unadorned quality of the store theaters, even if not displaying an overtly modern aspect, shared a similar purpose: as Barbara Wilinksy has written in her study of art cinemas, “the simple, modern design of a theater like the Film Guild provided what some cinéastes believed to be the proper environment for film viewing, in which all lines directed the eye to the screen, discouraging audience distraction.”118 As we have seen from contemporary observers, it was also the richness of the image that licensed the limited architecture: there was no need for elaborate settings since the images could provide so much, all the more so since they now had the label of advanced art. Looking at the development of movies in terms of the architecture used to display the image makes all the more evident how much interaction between movies and live-performance theater is central to the development of movies. Later movie theaters thrived on elaborateness of decoration; the store theater might seek a degree of “pretentiousness” by importing a few classical elements into its interiors, but for the most part elaborateness was restricted to façade. No doubt, a pared-down look was in large part a consequence of economics, but this does not mean the theaters were slapped together. How they would function still had to be thought about, as there is ample evidence in the trade press.

The store theater was a dead end to the extent that it was founded on an exhibition format that disappeared with the rise of the feature film. But it did effectively look ahead to the feature film by helping to establish the popularity of narrative film, film as a dramatic art, not simply a novelty element in the context of a vaudeville show. And as an architectural form, the first dedicated motion picture theater, it did have an impact on later film theaters in a number of specific areas: black masking around the image (although the rationale for doing this was lost); downlighting; rectangular form; frontal seating; light levels and continuous performances with a sit-anywhere policy that complemented the “democratic” seating plan; “pretentious” elements in decoration as a positive quality, a way of elevating the status of the object displayed by elevating the environment itself; a central concern with ventilation as a way of defining the environment. It is also in the store theater that the architectural screen emerges, a feature of neither the vaudeville theaters before them, nor the movie palaces after them. The notion that the screen might determine architecture was lost in the excitement over the movie palaces of the teens, but it would eventually emerge again in the sound period.

The “nickel theaters” that repurposed existing theaters, most often marginal vaudeville theaters, faced the familiar problem of how to make movies work within existing architectural spaces. In this context, the store theater had to be important because it represented the first sustained thinking about how the film image should be situated in architectural space, and it did so by challenging conventions of theatrical space. And even if the constricted space of the small theater and the great open spaces of the palace might seem to make the two polar opposites, the democratization of space in the store theater did have an impact on palace design. This, then, is the lasting achievement of the store theater: it convincingly demonstrated that virtually any interior space could be turned into a theater and achieve commercial success even as it undercut the hierarchical organization of space that was an essential feature of earlier theater architecture. Comfort, decorum, an architecturally pleasing environment, even a sense of luxury, all the things the trade press was calling for in order that a more refined setting could elevate a product aspiring to be art, none of this was needed if the play, or photoplay, really was the thing. I suspect the enduring myth of the accidental nature of the store theater lies in its impact outside of movie history, that it offered a model for all dramatic arts.