ART CINEMAS, CINEMA ART

As I conclude this narrative, I arrive at a period when the motion picture image in its most common use is beginning to move outside of the architectural spaces that had contained it for most of its history. This happened in two ways, the first moving the image into the great outdoors, the second into domestic space. In both cases, the image continued to be contextualized by a setting, but the setting was now radically removed from anything that suggested conventional theater. With that break, I would suggest, the status of the image itself began to transform. If the major transformation took place outside of theatrical space, within the space of the theater a different transformation took place as well.

While changes in screen design inevitably led to changes in architecture, there was one major development on the architecture front in the period leading up to the wide screen that had a powerful effect on screen technology and the status of the screen itself: the postwar period saw a boom in drive-in theater-building, previously a form of exhibition that had been primarily regional. In 1948, a survey by the Motion Picture Association of America revealed there were 743 drive-ins across the nation, of which 137 were “year-round operations.” Of these, the “majority…stick to a single-feature policy.”1 By 1950, the number had jumped to 1,980 and reached 4,700 by the end of the decade.2 The drive-in created conditions of exhibition unlike anything that had been seen in in-door theaters. For example, a car “even in the second ramp of a large theater [would be] at a point 173 feet from the screen…,” a distance much further than anything in the biggest palaces.3 And that was only from the second “row”: one Chicago drive-in in 1950 had a throw-distance from projector to screen of 475 feet.4 Because of the distances created by an audience of automobiles, drive-ins of necessity featured much larger screens than those in conventional theaters, even before the introduction of widescreen technologies (1952–1955). While Radio City Music Hall’s standard screen in the early fifties was exceptionally large at 33 feet, a 1949 article reported the “drive-in picture is seldom smaller than 40 feet wide.”5 In 1951, another Chicago drive-in reported a screen 70 feet wide, which happened to be the same size as the screen at Radio City Music Hall after the introduction of CinemaScope two years later.6 Many drive-ins did not convert to widescreen right away because in effect it meant replacing their largest building, but when they did, the Scope screens often far exceeded the widest in indoor theaters. The very size of these screens created problems of illumination never dealt with before, not least because outdoor conditions, even in rural areas, could often not depend upon the level of darkness possible in indoor theaters. Improvements in carbon arc technology, needed for drive-ins in the late forties, made possible the widescreen illumination in the fifties.7

Even more critical for my concerns here, the drive-in redefined how the screen related to architectural space by virtue of the fact that the screen itself was one of the very few architectural elements left from the conventional theater. There was a kind of architecture here to the extent that orderly spaces had to be laid out to mark where each car should park, with each space clearly designated by a pole for the portable speaker to be latched to the car window, but the architecture was more like a blueprint—an outline of forms on a flat surface—than an actual building, or, perhaps, a kind of invisible building. By its gargantuan size, the screen was the most visible element, but the extraordinary distance from viewers reached proportions far in excess of SMPTE’s recommendations. Still, because the screen provided the most prominent of the drive-in’s four architectural elements, alongside the combined projection booth–refreshment center, the ticket booth, and the marquee, it could achieve a dominance of its space unlike anything in indoor theaters before wide screen. In the drive-in, the screen was no longer an object defined by architectural space; rather, the screen had become the theater itself.

The drive-in screen possibly revived something of the uncanny aspect of the movie image by making it a spectral reality suspended in a night sky. On the other hand, the other postwar phenomenon to detach the screen from its theatrical context did place the film image in a specific architectural space. The spread of broadcast television was initially limited by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the postwar period, but then escalated throughout the 1950s, until it reached most Americans. In theory, the television image, potentially showing much the same things shown in movie theaters, could be shown anywhere. But early on, in spite of the movie industry’s attempts to link it to the theater through “theater television,” showing live events like boxing, television did become identified with a type of architectural space—the home. From a survey of home magazines of the early fifties, Lynn Spigel has shown how the television set was made a domestic object: “As the magazines continue to depict the set in the center of family activity, television seemed to become a natural part of domestic space…. Photographs, particularly in advertisements, graphically depicted the idea of the family circle with television viewers grouped around the television set in semicircle patterns.”8

The space around the image was now more individualized, and how people positioned themselves in relation to the image was now more a matter of choice. Movies had been literally domesticated in the home, but the drive-in was also marketed as a family experience: admission at many drive-ins was by car, not individual viewer, or else children were admitted free, with the expectation that both policies would encourage family attendance; the space of the car was a personal family space transported to the moving image; and the drive-ins offered activities for the entire family, ranging from laundromats to playgrounds with concession stands that could be used for dinner.9 That is, the drive-in also served to individualize space by offering a variety of options for each individual, only one of which actually involved watching a movie. Ultimately, in both the case of the drive-in and the home, the image had lost the aura granted it by the theatrical space. Now it was simply one element within a space for a variety of activities.

It would take another forty years or so for the cinematic image to be fully divorced from specific architectural spaces, finally achieving the ubiquity that was always inherent in the medium. Consequently, we live in a world that surrounds us with moving images, in every conceivable kind of architectural space as well as outdoors: they have become an inescapable part of our lives. As potential contexts for the texts were becoming increasingly varied, cinema’s seeming existential bond to theater, purportedly proven anew by the arrival of This Is Cinerama, was fading. As my journey through the varying configurations between image and architecture that took place in the space of the theater over a 60-plus-year period has returned me to my point of departure, I would like to echo a comment frequently heard in continuous-performance movie theaters: “This is where I came in.” But in sketching out more of the context for the claim that film was and is an art of the theater, I find this affirmation more complicated than might appear at first glance.

Most saliently, there is a double irony in Motion Picture Herald’s use of Cinerama as a demonstration of film’s theatrical essence. First off, installing Cinerama required a radical reorientation of architectural space within the theater: the projection booth at the rear of the balcony became a useless relic of the past; in its place three separate projection booths had to be built at the back of the orchestra; seating capacity had to be reduced so that all viewers would be within an angle to receive the impact of the Cinerama effect; a seeming warehouse full of drapery covered over the once-lauded architectural detail of the auditorium, both to let the screen dominate the space, but also to improve the acoustics for a seven-channel sound track, with sound originating in the auditorium itself as well as behind the screen; and, most importantly for my concerns, the apparent elimination of the most visible signifier of live theater, the curtained proscenium arch—in the first New York installation the oversized deeply curved screen, 51 feet wide by 26 feet high, had to be placed in front of the proscenium. Second, the five Cinerama features exhibited from 1952 to 1962 were in many ways closer to the kinds of film that predated the rise of the feature film, which early on positioned itself as the direct competitor to the legitimate theater: This Is Cinerama is basically a two-hour travelogue, which pretty much describes the next four Cinerama releases, with occasional gestures made toward narratives, but always narratives of tourism. As John Belton has noted, “The Cinerama medium is ideally suited to the ‘nature’ documentary and the sightseeing excursion.”10 The cost of installing Cinerama was sufficiently prohibitive that the initial showing of This Is Cinerama was limited to only seven theaters. In spite of this and the generally limited box office appeal of feature-length travelogues, within fifteen months the film was expected to gross $6.5 million.11

Cinerama managed to turn a profit over a ten-year period with travelogues and a limited number of theaters–$82 million in only twenty-two theaters—but “each successive Cinerama picture earned less than the one before.”12 It was clear that continued growth and profitability would require both a move to narrative films and a substantial increase in the number of theaters equipped to show Cinerama. The two went together: The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), the first of a series of features MGM committed to make in Cinerama, turned Loew’s flagship Capitol in New York City into the Loew’s Cinerama, a couple of blocks north of the Strand, which had become the Warner Cinerama ten years earlier.13 In contrast to the legitimate theater where it premiered, the spatial dimensions of the great palaces were more suited to Cinerama: the screen at the Capitol, heralded in the advertisements as “Super Cinerama,” at 90 feet wide by 33 feet high, approached doubling the size of the original Cinerama screen.14 At the same time, sightline requirements of Cinerama dictated a drastically reduced seating capacity, cutting the Capitol’s 5,300 seats down to 1,525.15 With commitments from MGM and United Artists to make narrative features in the process as well as a move away from the three-projector technology to a single 70mm projector, Cinerama announced a theater-building plan with a design based on Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, hoping to build 300 theaters in the United States and another 300 theaters abroad, what I would like to call theaters of the future because this was a design based in technology, a form appropriate for an art based in technology.16 While a limited number of new theaters were built, in the United States only the Los Angeles Cinerama theater utilized the dome design. Repurposed movie palaces remained the primary venue for the process, and it did initially help them survive the precipitous box office declines of the sixties. The Capitol/Loew’s Cinerama, for example, remained a successful exhibitor of Cinerama films through 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968.

Making a commitment in the early 1960s to build 300 new theaters might seem foolish in the face of competition from television, but this was actually part of a trend, heralded by a New York Times headline in 1962, “Movie Theaters at Building Peak,” with 183 new indoor theaters (as opposed to drive-ins, which accounted for another 95) beginning construction in the previous two years. Many of these were in response to the postwar growth of the suburbs, as the Times noted: “Long Island claims the largest concentration of new theaters within a single area, with 29, most of these in the suburbs near Manhattan.” New York City itself saw five new theaters open in the same period. But these theaters were moving in a very different direction from the Cinerama theaters: “The local pattern [in New York], which is indicative of the national trend, has been toward the development of small ‘art houses,’ with many of the large old ‘movie palaces’ converted to reserved-seat operations for long runs of the spectacle type of films.”17 Emblematic of this shift, a new theater opened on New York’s East Side about six weeks before the transformed Capitol debuted as a Cinerama theater. Dubbed “Rugoff’s Unique Cinema I–Cinema II,” these duplex theaters pointed to a different direction for theatrical exhibition in the age of television, a direction that would effectively set the pattern for future theaters.18 Cinemas I and II would become a landmark in what Variety called the “New B’way,” heralding a shift away from Broadway as the primary site for extended-run films: “If the building trend continues along Third Ave., industryites envision the street as the new home of important first-run pictures, including hardticket entries.”19 Most of these new theaters were art houses, and there were enough of them to lead the New York Times to run a map showing their locations.20 The reasons for the shift had to do with the growing importance of international art cinema to American exhibition.

In an article on plans for the two auditoria that made up Cinemas I and II, Variety specified that the “larger theater will play both Hollywood product, including hardticket entries [i.e., a reserved-seat, two-a-day run], or foreign product that has a larger appeal,” while the small theater would be for “specialized art films” (“Rugoff–Becker’s 2-Level Theatre”). The possibility of reserved-seat bookings might seem odd for an art house, but what was intended here was not the kind of big-budget movies getting roadshow treatment on Broadway at the time. The context for this statement was the postwar revival of reserve-seat extended-run cinema, which began not with Hollywood spectacles of the 1950s, as often assumed, but, rather with the British invasion in the postwar period, kicking off with Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1946). British films in particular achieved runs far in excess of anything achieved by a Hollywood film since Gone with the Wind: a bit over a year for Henry V, fifteen months for Hamlet (1948), and over two years for The Red Shoes (1948). As in the 1920s, when Hollywood sought to present itself as the successor to the legitimate theater, the length of the run became part of the movie’s exploitation. For Hamlet, Universal-International gave out a press release boasting that fifty-eight weeks (and still showing) “establishes the run of the film as the fourth longest ‘of any motion picture in New York history.’”21 And about two months before The Red Shoes finally closed, an advertisement exclaimed, “100th Week! In The All-Time History of Broadway…There Has Never Been A Run Like…There Has Never Been A Hit Like…There Has Never Been A Motion Picture Like…”22

The old pattern of booking films into legitimate theaters in or near the Times Square theater district was used for Henry V and The Red Shoes. But Hamlet was treated differently, opening in a 475-seat theater on the East Side on a street lined with the city’s most exclusive apartment houses in a space that had previously housed an art gallery—a theater so exclusive that it began its first year with a yearly subscription fee. As the Park Avenue–art gallery ambience of this theater suggests, the extended-run engagements, whether two-a-day or grind, that would become common in East Side theaters were different from the roadshow engagements that took over the demotic palaces on Broadway in the 1950s. The implication was always that these were films aimed at a discriminating audience, much like the one Gloria Gould was wooing for the Embassy in 1925. Commensurately, the theaters didn’t sell popcorn, but many did feature espresso in their lobbies and sometimes even artwork for sale on their walls, the products serving to define the patrons, either in actuality or aspirationally.23 Because of the common language, however foreign the accent, British films such as Great Expectations (1946), which opened at Radio City Music Hall, could play in more conventional movie theaters.24 But as the East Side exhibition circuit grew larger, more British films, especially those that seemed more culturally specific, sought long exploitation runs in these small-scale theaters and for reasons similar to the long runs in the 1920s: to help sell the films outside of New York.25

If British films had occasional success in the American market in the past, one of the most striking features of the postwar period was the increasing movement of foreign-language films outside of the niche they had previously occupied. To do this, a successful New York run was essential. So, for example, a film like Diabolique (1955) could end up playing in neighborhood theaters outside of New York in French and with subtitles. In 1961, La dolce vita became one of highest-grossing foreign films in the domestic U.S. market. The rising popularity and new commercial potential of the international art cinema gave a renewed impetus to the bifurcated releasing system: by the late sixties, Hollywood would open small-scale but artistically ambitious films in the growing number of East Side art theaters in New York with the expectation of runs that would go on for several months, exploitation for the mass release that would follow. A Broadway opening, on the other hand, was for movies with more mass-market appeal, with the biggest-budgeted ones receiving the roadshow treatment.26

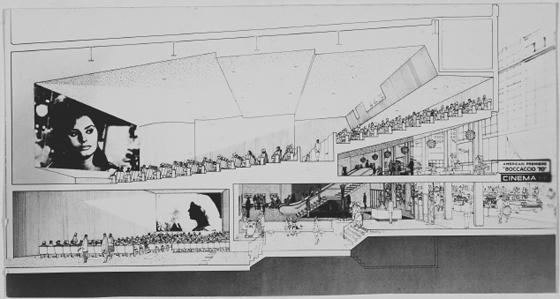

The rise of the art film suggests that Variety was wrong to call the East Side theaters a “New B’way.” If anything, it was more like Off-Broadway, which began to become an important force in New York theater after the war. But ultimately the move to the East Side might best be seen as a move away from theater altogether. Within this new emerging movie district, Cinemas I–II sought distinction, and most of all did so through architecture. In the first announcement of plans for the new theater, about sixteen months before the theater opened, Ben Schlanger, who had done a number of other theaters for Rugoff, was listed as the sole architect: “In preliminary drawings by Ben Schlanger, designer of the Murray Hill Theatre and one of the architects for Lincoln Center, a 750-seat theatre will occupy the main floor, with a 250-seat auditorium on a lower level.”27 Somewhere in the process of developing this building, the name of Andrew Geller was added. At the time, Geller, described in an obituary simply as “Modernist Architect,” was best known for his domestic and commercial architecture; as far as I can determine, the Cinemas I and II was his first and only theater building.28 The architects of the great palaces from the teens and twenties built reputations on the basis of their theater buildings, but their specialization has likely kept them out of most histories of twentieth-century architecture.29 Like them, Schlanger, although as much the modernist architect as Geller, did not have a reputation outside of theater architecture circles. Engaging Geller ensured that the building itself would receive notice, which it did—two articles in architecture journals as well as a feature article in the New York Times with a large reproduction of the “Architect’s sketch” to show how the design of the theater worked.30 The theater’s distinction was also acknowledged by the Municipal Art Society of New York, which awarded Geller and Schlanger a Certificate of Merit “for the design of two motion picture theatres, Cinema I and Cinema II, which bring the qualities of elegance and reserve to a field in which they most usually are absent,” as well as two other awards for architecture.31

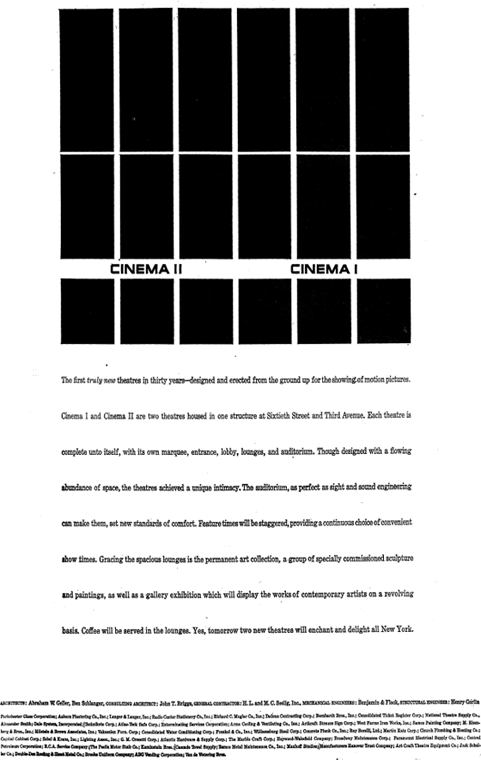

The class connotations in “elegance” and “reserve” that lift these theaters outside the commercial vulgarity of past theater-building point to another referent embodied in the architecture. The Architectural Forum article singles out one aspect of the façade worth considering here: “The first theater building with an open façade in New York City, Cinema I has a second-floor lobby which is an inviting showcase for passers-by” (121). This was a marked difference from past theaters, where light was effectively kept out: a theater that was part of an office building would have conventional windows in its façade, but this great expanse of glass across the width of the building was unusual (fig. C.1). There was, nonetheless, a model for this design: Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. To keep an architectural harmony, the three central buildings—the Metropolitan Opera House, flanked on either side by the New York State Theater and Philharmonic Hall—all had an arcaded façade, like Cinemas I–II, and second-floor lobbies visible through glass along with the chandeliers and artworks inside (fig. C.2).32 Like Cinemas I–II, which partitioned the massive window with marble-sheathed pilasters, the glass façades of the three Lincoln Center theaters were partitioned by white columns of varying designs. There was a fourth building, one for drama, but it was much smaller, and tucked away behind Philharmonic Hall; although it used a glass façade facing into a ground-floor lobby, the overall design was different from the three central buildings. While the Lincoln Center model is evident in its design, Cinemas I–II audaciously opened three months ahead of the first Lincoln Center building, Philharmonic Hall. (Figure C.3 foregrounds the key elements of the design via abstraction in an advertisement announcing the opening of the theaters.)

How, then, could Lincoln Center serve as a model? Architectural drawings of the three buildings had already appeared.33 More important, Ben Schlanger was one of the architects involved in Lincoln Center, as the first announcement in the Times noted, back when Schlanger was the only architect listed for Cinemas I–II and had already provided “preliminary drawings.”34 It would take Lincoln Center three decades to add its own film theater; in the meantime, Cinemas I–II could become the premier space for film as one of the arts, not film as an analog to theater. And the Rugoff chain clearly wanted the resemblance to be noticed: an undated press release from the time stated explicitly, “Cinema I-Cinema II are planned as the core of an International Film Center on the East Side, which will act as a crosstown complement to Lincoln Center.”35 Further, most Rugoff press releases highlighted Schlanger’s connection to Lincoln Center. The point was to recognize film as its own art form, not a derivative of the stage, something that warranted its own structure, much as each of the arts at Lincoln Center had its own building. A full-page ad that ran the day before the opening pressed this claim: “The first truly new theaters in thirty years—designed and erected from the ground up for the showing of motion pictures.”36 The claim that the theaters were innovative because they were designed solely for movies echoes claims made for the 1929 Film Guild Cinema, the “first 100% cinema,” as described in this volume’s introduction; but even that theater with its elaborate camera-like iris around the screen and plan for projected images all over the auditorium seemed to embrace the extravagance that was typical of the period. By contrast the auditoria of Cinemas I–II were almost nondescript.

It is not possible to prove that Schlanger provided the Lincoln Center connection, or who in fact should receive credit for which aspects of the building. Schlanger did write to Geller a number of times pointing out they had agreed they should always be listed equally as architects.37 It is evident the auditoria were entirely Schlanger’s work, both from echoes of Schlanger’s other theaters as well as the advertisement, which seems to tout an architect who embraced engineering “as perfect as sight and sound engineering can make them.” The larger auditorium in particular seems a reworking of a design he had provided the Rugoff chain with the Murray Hill Theatre three years before, but both Cinemas I–II auditoria had features typical of Schlanger, from the Synchro-Screens to the seating arrangements (in the larger theater, a modified stadium arrangement and continental seating to eliminate aisles) to the neutral wall treatments (fig. C.4).38 As significant as these elements were, equally significant was what the theaters lacked: no stage, no proscenium and, most importantly, no curtain.39 This has since become a convention of movie theater architecture, but at the time curtains were the last vestige of conventional theaters still being included in other new theaters. Pulling back the curtain, so to speak, was Schlanger’s way of realizing an ambition from his earliest architectural designs, the culmination of film asserting its own artistic identity.

Much as using the screen to define architectural space looked ahead to future movie theater architecture, the form of the dual theater design, which garnered the most comment at the time, looked ahead in terms of function to the mulitplex. The theater was seen as innovative, although it was hardly the first duplex. Like the Duplex Theater of Detroit described in the introduction, the design was a response to developments in production, but very different circumstances led to a different design and a different set of goals. The theaters were not twins; rather, they were piggybacked with very different seating capacities (fig. C.5).40

A Variety article explained the function: “Policy is a flexible one. Both theatres might play the same picture at different curtain times…. Could be, too, that the 300-seater will run an import while the 700-seater plays a non-art entry, or the 300-seater will take a picture from the 700-seater on a move-over run.”41 More important for the future direction of exhibition was the combination of certain kinds of Hollywood films, foreign films with broader appeal, and films aimed at a narrower audience. The combined theaters meant that the commercial success of the larger auditorium could help sustain the limited cash flow of an extended run in the smaller auditorium, essentially setting up the pattern that would be utilized by the later multiplex. Given the way the theater had positioned itself as the most distinguished setting for the art of film, it quickly became the most sought-after booking for Hollywood’s artistically ambitious films such as Mean Streets (1973) and Days of Heaven (1978), with the theater granted an exclusivity that had once been reserved for pre-release theaters in the classical period. And it maintained its artistic aura by alternating Hollywood art with foreign films with popular appeal and big international stars such as Boccaccio ’70 (1963), its opening film, and Tom Jones (1963), as well as smaller-scale imports such as Il Posto (1963).

Rather than say that cinema in this period discovered its true vocation, as Siegfried Kracauer wanted it to when he complained about Berlin’s presentation houses, I would prefer to posit that the prestige of Cinemas I–II and the consequent shift away from Broadway to the East Side signaled how much cinema began to loosen its tie to theater.42 The best evidence for this is the move away from theater itself as a source for movies. In its earliest decades, drama was one of the primary sources for feature films (and continued to be with occasional ups and downs). But from the 1970s on, adaptations of stage plays decline rapidly, as the chart in figure C.6 demonstrates. (For a more precise breakdown, see appendix 2.) At a certain point, Hollywood became more likely to look to old television shows and comic books as prime source material for mass market movies rather than to the theater. And with the rise of the international art cinema and eventually a native American art cinema, serious movies no longer defined their seriousness by claims of being the successor to theater, but rather asserting their status as an entirely separate art form.

CURTAINS FOR CINERAMA

If Schlanger’s Synchro-Screen (“the poor man’s Cinerama”) could, like Cinerama, seem a way of redeeming the giant space of a palace, in the context of a smaller theater it functioned differently: here it was not the poor man’s anything, but rather the theater’s defining architectural element, refusing to be concealed by a curtain, in its own way effectively announcing the independence of film art. On the other hand, the curtain was a key part of Cinerama’s exhibition protocol, as exemplified by this ad copy for Search for Paradise (1957), the fourth Cinerama travelogue, which emphasizes: “When the theatre lights dim and the curtains open…and open…and open—you are plunged into the entertainment experience of your lifetime.”43 This Is Cinerama, the first film, began with a conventional 1.33 black-and-white introduction, narrated by noted journalist and radio commentator Lowell Thomas, and projected at a size that would have been used for ordinary movies. The Cinerama curtain was located very close to and directly in front of the screen, following a track of the screen’s curvature. An audience seeing Cinerama for the first time could assume much of the curtain was decorative, and, indeed, for the Thomas prologue, the curtain opened only as wide as the initial small-screen image. Concluding his twelve-minute introduction, which had provided a brief history of art (from cave painting to the Renaissance in forty seconds), then moved on to the various technological innovations to make images move and then speak, Thomas finally intoned in his well-known stentorian voice, “Ladies and Gentleman, this is Cinerama!” At which point the full Cinerama image, all three panels, flooded the screen (although the image was a bit obscured since it was in a dark enclosed space at the beginning of the roller coaster ride at Rockaways’ Playland. The contents of the image seem timed to the movement of the curtain since it took forty seconds for the roller coaster to reach the top of the first incline and the first truly panoramic view, the curtain signaling the drama of our realization that we are looking at an image much bigger than just three times the size of the conventional image, an image both taller as well as much wider.44 From this peak, as the car began its precipitous descent, screaming was heard throughout the theater. The screams didn’t emerge from anyone visible in the image, but the audience could hear them all around the auditorium thanks to seven-track stereophonic sound. And the audience could well understand why the screamers seemed to be in their midst since the image, playing on the viewer’s peripheral vision, effectively created a very powerful sense of vertiginous movement. As John Belton notes, there were reports of brisk Dramamine sales at nearby drugstores during the intermission. This was the “Cinerama effect,” and every Cinerama film thereafter featured its own “roller coaster” moment, even the narrative films that began to be made in 1962.45

The fact that the narrative films also embraced the roller coaster effect does suggest something different about the Cinerama features that is worth exploring. It is not at all unusual in the history of American film for films featuring a new technology to find ways of exploiting that technology, foregrounding it more than later films would. But by the time Cinerama turned to narrative, the technology was ten years old, and yet it still needed its roller coaster moment. Since the travelogues literally traveled, it was easy enough to provide a sequence of dizzyingly rapid movement, with images shot from airplanes especially favored. But how to motivate such a sequence in a narrative film? How, for example, could a western, How the West Was Won (1962), the second Cinerama narrative feature, end with a series of breathtaking and, yes, vertiginous aerial shots? Only by moving outside its narrative confines to provide a tour of the contemporary American West, presumably the fruits of what had been won within the narrative. That American filmmakers understood Cinerama as creating a very different experience of space is perhaps evident from the fact that Warner Bros. announced in 1956 that it was considering Cinerama for a film version of The Miracle, the Max Reinhardt play that in the 1920s turned an entire theater into a cathedral, altering the way an audience experienced a stage setting. But the roller coaster effect was something different, a thrill experience that really existed apart from the narrative, like the ending of How the West Was Won.

Ordinarily, Hollywood filmmakers would try to locate motivation in the narrative and seek appropriate stylistic devices to present such events, but here the technology itself motivated the moment. This signifies an important difference that was understood by a review of The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), the first narrative film in the process: “Although the performers, from stars to bit players, are uniformly ingratiating—and properly nasty as occasion requires—if there is a star that shines beyond compare in this two hour and 15 minutes show (plus intermission) it is special effects.”46 There was always a demand for the Cinerama sights to be so impressive that we could overlook the flaw of the very visible lines that demarcated the three images. But the particular nature of this spectacle was its sense of presence, the way in which the film image seemed to overwhelm the reality of the theatrical space we inhabited. This was the value of travelogues for Cinerama, the ability of the process to give us the illusion that the image of real places merged with the auditorium, even extending into the seating area. In effectively making us tourists, Cinerama obliterated the fourth-wall aesthetic that regarded the proscenium as a picture frame, an understanding shared by late-nineteenth-century theater practitioners and early dramatic filmmakers. And it was precisely that possibility for merger that led Schlanger to object in 1935 to the very name “motion picture” in terms that seem to anticipate Cinerama: “The viewer of the motion picture should not be looking at a picture or through a picture frame; rather, he would like to feel as though he existed at and when the action is supposed to be taking place, even though the ‘subject’ may be past history.” From early on, a guiding principle of Schlanger’s theater design was that the ideal film image should have no defined shape: “the particular beauty or form and proportion of its shape are of no importance. As contrary as it may seem, it is the apparently ‘shapeless shape’ that is most adaptable for the motion picture—a shape that would make the viewer the least conscious of a limited boundary.”47 The slow opening of the curtain that always began a Cinerama movie rendered the screen a shapeless shape, seemingly boundless as it extended to our peripheral vision. For a travelogue, the curtain might have seemed a vestige of theatricality, but it was essential to Cinerama performances because the curtain served to make the reality of the image itself dramatic.48 The move into fiction filmmaking after a decade of travelogues should have located the drama back in the action, but technology effectively foregrounded the drama of the image and made the reality of the fictional world magical.

Making special effects the star, and doing it so forcefully that it warrants all caps, represents a transformative moment, one that looks ahead to the cinema of the future, a future that begins to be realized with the last Cinerama feature to play at the reconfigured Loew’s Capitol, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Although the film was still drawing crowds, it lasted in its premiere house only five and a half months because the Capitol was scheduled for demolition to make way for an office building and a new legitimate theater.49 2001 moved two blocks south to continue its reserved-seat run at New York’s other Cinerama theater, proving to be one of the more popular of the 1960s big-budget roadshow releases.50 Yet much as the film looks ahead to the future literally in its plot and figuratively in its style, it would be impossible to conceive of this film being produced were it not for the commercial success of the art cinema in the period leading up to it. Starting with the main title, an alignment of planets is a key visual motif in this film, appropriately since the film itself now seems something that could happen only by an alignment of the stars, creating just the right circumstances for such an oddball success. It is an art movie or, more precisely, an art movie as the period understood it, which means slow-moving, underplayed, and, by the end at least, obscure in its meaning. Furthermore, there are long periods without dialogue: we are twenty-two minutes into the film before we hear anyone speak, while the entire final section (“Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite,” all twenty-three and a half minutes of it) has only one character and no spoken language.51 Finally, the only actor who might qualify as a star, Keir Dullea, does not appear until about fifty-five minutes into the film. Possessing qualities that would certainly alienate a twenty-first-century audience seeking spectacle, it is also the most expensive art movie ever made, which means it is not an art movie for Cinema I, where Kubrick’s next film would premiere, but rather a movie made for a grand space like the palatial Loew’s Capitol.52

Early film theory often focused on defining the essence of cinema, certain that whatever it might be, it was not theater. On the other hand, American practitioners in the early days of the narrative feature film were convinced that’s exactly what they were doing and doing so within spaces that came out of live theater. Ultimately, there is no essence of cinema or, rather, the essence is malleable, our perception of the text constantly changing as contexts change, as I hope this study has shown. Motion Picture Herald on Cinerama as an art of the theater notwithstanding, 2001 seems to me a film poised between the cinema of the past and the cinema of the future, a film unlike anything that came before it, and yet still at times drawing on past conventions for its effectiveness. Much as it repeatedly underplays its drama, the film’s middle section (titled “Jupiter Mission—18 Months Later”) is at sixty-two and a half minutes its longest, straddling the intermission, and is also the section with the most conventional markers of a dramatic work. This section has the most extended dialogue sequences, and—with one important exception—the dialogue mostly takes place between humans who speak in robotic monotones and an ingratiating computer who likes to talk about his feelings. Despite this contrast, we gradually perceive an increasing distrust of the computer, especially by Dave (Keir Dullea), that contributes to a growing and quietly dramatic sense of menace throughout this section. This menace is fully realized in the chilling twenty-minute suspense sequence that begins the second half of the film, a sequence in which HAL systematically kills Frank (Gary Lockwood), the only other character we have gotten to know; removes the life support from the three hibernating astronauts also on this mission; and then tries to kill Dave, which leads to Dave’s eventual destruction of HAL.

In this middle section especially, it seems clear that Kubrick was utilizing the unusual size and shape of the Cinerama screen.53 The section begins with the first instance of the roller coaster effect as Frank runs inside a giant wheel that makes up the living and working areas of the spacecraft, a high-angle camera looking down on him and tracking forward as he runs, our peripheral vision viscerally affected by the various objects alongside the floor he runs on.54 However, at the beginning of this sequence, Kubrick’s first shot of the interior (perhaps to suggest how the space relates to the exterior of the craft seen in the previous shot) has the floor as a vertical on the left side of the image, so that Frank appears to us horizontally, seemingly suspended in space, which he literally is. The effect is to make apparent in the next shot something that perhaps was always inherent in the roller coaster effect, namely that much as it seems to present a continuous space, it is also profoundly disorienting. The two shots that follow from it create a further dizzying effect: a low reverse-angle shot of Frank tracking backwards that makes the floor look like a ceiling, a disturbance underscored by our ability to make out objects along the floor/ceiling that look like sarcophagi with little glass windows through which we can see faces; then another high-angle shot following Frank, but this time much closer in and oriented in such a way that makes it look as if he is about to fall on the floor he is running along. From this point on, the style of the film changes from its first two sections—the camera, even when still, repeatedly assuming positions that, aided by a complex set design, puts objects and characters or the two characters to each other at odd, precipitous angles. Emphasizing the disorientation are the many point-of-view shots for HAL, the panopticon who sees and hears everything on the ship, while there are no point-of-view shots for the human characters. Even as the drama seems to be taking a turn toward the conventional, the images themselves are at their most unconventional, but here serving the dramatic purpose of making the environment itself a source of unsettling disturbance. That is, up until…

That one important moment. In its initial showings, 2001 featured possibly the most powerful coup de theatre I’ve ever experienced in a movie house, an experience I’ve never forgotten and so directly connected to a specific theatrical space that no contemporary exhibition of this film can re-create it outside the small number of Cinerama theaters left in the world. I had previously written about the mysterious movement of the Fantom Screen as a coup de theatre, but one that was created entirely by its unexpected manner of exhibition. 2001 is different to the extent that this moment, as with most plays, is immanent in the text, but made fully theatrical since the film was effectively integrated into a kind of performance in its initial showings.

In the lead-up to this coup, Dave and Frank have individually become concerned that something is not quite right with HAL, and they need a place to talk outside his purview. They choose an enclosed private pod used to travel around the ship, under the pretense that there is something wrong with its communication system. Making sure that HAL cannot hear them, they begin to discuss their suspicions. Meanwhile, there are two things to note about how this scene functions in the film. First, this is actually the only conversation that Dave and Frank have together, although they’ve been in the film for about half an hour by this point. Second, as if to reflect this fact, the shooting style becomes more “normal,” no longer resorting to the odd angles used previously. In fact, the image achieves a real stability that is almost comforting in its context, as the world seems to have become more settled and secure: it is now completely symmetrical, with the backs of their two chairs occupying the left and right of the image, with Dave on the left and Frank on the right, facing each other with similar profiles, while between them, in the middle of the screen, there is an oval window through which we can see a computer terminal. Here, however, an asymmetry created by two elements introduces a new sense of disquiet: HAL’s red eye on the terminal just to the right of center and behind it a spacesuit and helmet displayed as if it were a person, the conflation of inanimate and animate echoing the computer’s seemingly human personality (fig. C.7).

Before I describe the rest of the scene, however, I need to note that in nineteenth-century theater—and even later—the curtain could be an important part of the coup de theatre, a very rapid drop of the curtain following the unexpected turn of events, leaving the audience astonished about what they have just seen and very uncertain about how things will proceed. We’ve already seen that the curtain was important to early Cinerama presentations, but advertising descriptions of the curtain opening effectively conveys an essential part of the presentation: because the curtain was on a deeply curved track almost flush against the screen, it always moved very slowly. The opening of 2001 seems to acknowledge this because the unusually stylized MGM logo is positioned very narrowly within the dead center of the image, which is where the initial titles remain. It is over a minute into the film that the main title, 2001: A Space Odyssey, appears across the width of the screen.

Now back to Frank and Dave in the pod: troubled over HAL’s increasingly strange behavior, they discuss what to do next. When they conclude they might have to disconnect HAL, there is a closer shot through the window of the computer terminal, seeming to reflect where Frank and Dave are looking, as they discuss how to manage the task. Cut back to the two-shot of Frank and Dave, and right around this point in the scene, the curtains began to close…and close…and close. As the curtains effectively create a drama that was not quite in the text, we wonder why, why are they closing before we have any sense of where the narrative is going? The last audible dialogue we hear from Dave will lead to a visual revelation: noting that no computer of this sort has even been disconnected before, Dave turns his head toward the terminal and makes HAL fully human as he worries, “Well, I’m not so sure what he’d think about it.” At this point, there is a cut, as if in response to Dave’s statement, to an extreme close-up of HAL’s red eye. With the curtains now more than half closed, a reverse-angle shot suddenly shows HAL’s point-of-view—with Dave now on the left and Frank on the right—and an iris shot of Frank’s lips as he speaks.55 The camera is about to move, and that movement could conceivably have been expressed by moving the iris, but the movement stays within the iris so that the image appears in the one part of the screen the curtains have not yet reached. The camera pans to the left, watching Dave’s lips move in close-up, then to the right and back to Frank’s lips, then once more to Dave. At the moment we realize that HAL is lip-reading, the curtains have completely closed, through which we can read: INTERMISSION.

It is precisely the antidramatic strategy of much of Kubrick’s narrative that makes the theatrical gesture of the curtain’s closing so intensely dramatic. This was indeed a moment that truly belonged to the theater. Other movies after this have had effective moments that could rank as a real coup de theatre—could anything be more startling than the chest-busting scene in Alien (1979), for example? But I cannot think of a film since then whose effectiveness was so tied to the space in which it was exhibited. Ben Schlanger’s movie theater interiors—with their anticipation of stadium seating, the neutral walls and their uncurtained screens—might have looked ahead to theaters of the future, while Cinerama tried to make sense of theaters of the past. But with this one startling moment of an interaction between curtain and screen, Cinerama, looking back to the nineteenth-century panorama, and 2001, looking ahead to the late-twentieth-century’s effects-driven movies, heralded a final transformation: in a single coup, living pictures, life-size pictures, moving pictures, motion pictures, movies, photoplays, talkies, cinema—all became a lost art of the theater.