“IT is beautiful,” says a character in Xenophon’s Economics,

to see the footgear ranged in a row according to its kind; beautiful to see garments sorted according to their use, and coverlets; beautiful to see glass vases and tableware so sorted; and beautiful, too, despite the jeers of the witless and flippant, to see cooking-pots arranged with sense and symmetry. Yes, all things without exception, because of symmetry, will appear more beautiful when placed in order. All these utensils will then seem to form a choir; the center which they unite to form will create a beauty that will be enhanced by the distance of the other objects in the group.1

This passage from a general reveals the scope, simplicity, and strength of the esthetic sense in Greece. The feeling for form and rhythm, for precision and clarity, for proportion and order, is the central fact in Greek culture; it enters into the shape and ornament of every bowl and vase, of every statue and painting, of every temple and tomb, of every poem and drama, of all Greek work in science and philosophy. Greek art is reason made manifest: Greek painting is the logic of line, Greek sculpture is a worship of symmetry, Greek architecture is a marble geometry. There is no extravagance of emotion in Periclean art, no bizarrerie of form, no striving for novelty through the abnormal or unusual;* the purpose is not to represent the indiscriminate irrelevancy of the real, but to catch the illuminating essence of things, and to portray the ideal possibilities of men. The pursuit of wealth, beauty, and knowledge so absorbed the Athenians that they had no time for goodness. “I swear by all the gods,” says one of Xenophon’s banqueters, “that I would not choose the power of the Persian king in preference to beauty.”3

The Greek, whatever the romanticists of less virile ages may have fancied of him, was no effeminate esthete, no flower of ecstasy murmuring mysteries of art for art’s sake; he thought of art as subordinate to life, and of living as the greatest art of all; he had a healthy utilitarian bias against any beauty that could not be used; the useful, the beautiful, and the good were almost as closely bound together in his thought as in the Socratic philosophy.* In his view art was first of all an adornment of the ways and means of life: he wanted his pots and pans, his lamps and chests and tables and beds and chairs to be at once serviceable and beautiful, and never too elegant to be strong. Having a vivid “sense of the state,” he identified himself with the power and glory of his city, and employed a thousand artists to embellish its public places, ennoble its festivals, and commemorate its history. Above all, he wished to honor or propitiate the gods, to express his gratitude to them for life or victory; he offered votive images, lavished his resources upon his temples, and engaged statuaries to give to his gods or his dead an enduring similitude in stone. Hence Greek art belonged not to a museum, where men might go to contemplate it in a rare moment of esthetic conscience, but to the actual interests and enterprises of the people; its “Apollos” were not dead marbles in a gallery, but the likenesses of beloved deities; its temples no mere curiosities for tourists, but the homes of living gods. The artist, in this society, was not an insolvent recluse in a studio, working in a language alien to the common citizen; he was an artisan toiling with laborers of all degrees in a public and intelligible task. Athens brought together, from all the Greek world, a greater concourse of artists, as well as of philosophers and poets, than any other city except Renaissance Rome; and these men, competing in fervent rivalry and cooperating under enlightened statesmanship, realized in fair measure the vision of Pericles.

Art begins at home, and with the person; men paint themselves before they paint pictures, and adorn their bodies before building homes. Jewelry, like cosmetics, is as old as history. The Greek was an expert cutter and engraver of gems. He used simple tools of bronze—plain and tubular drills, a wheel, and a polishing mixture of emery powder and oil;5 yet his work was so delicate and minute that a microscope was probably required in executing the details, and is certainly needed in following them.6 Coins were not especially pretty at Athens, where the grim owl ruled the mint. Elis led all the mainland in this field, and towards the close of the fifth century Syracuse issued a dekadrachma that has never been surpassed in numismatic art. In metalwork the masters of Chalcis maintained their leadership; every Mediterranean city sought their iron, copper, and silver wares. Greek mirrors were more pleasing than mirrors by their nature can frequently be; for though one might not see the clearest of reflections in the polished bronze, the mirrors themselves were of varied and attractive shapes, often elaborately engraved, and upheld by figures of heroes, fair women, or gods.

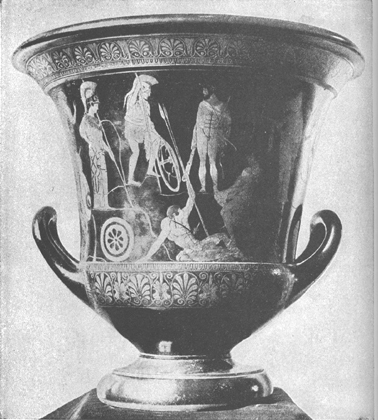

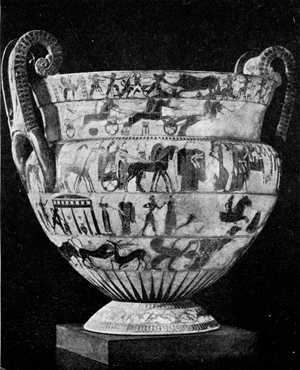

The potters carried on the forms and methods of the sixth century, with their traditional banter and rivalry. Sometimes they burnt into the vase a word of love for a boy; even Pheidias followed this custom when he carved upon the finger of his Zeus the words, “Pantarkes is fair.”7 In the first half of the fifth century the red-figure style reached its apex in the Achilles and Penthesilea vase, the Aesop and the Fox cup in the Vatican, and the Berlin Museum Orpheus among the Thracians. More beautiful still were the white lekythoi of the midcentury; these slender flasks were dedicated to the dead, and were usually buried with them, or thrown upon the pyre to let their fragrant oils mingle with the flames. The vase painters ventured into individuality, and sometimes fired the clay with subjects that would have startled the staid masters of the Archaic age; one vase allows Athenian youths to embrace courtesans shamelessly; another shows men vomiting as they come from a banquet; other vases do what they can for sex education.8 The heroes of Periclean vase painting—Brygus, Sotades, and Meidias—abandoned the old myths, and chose scenes from the life of their times, delighting above all in the graceful movement of woman and the natural play of the child. They drew more faithfully than their predecessors: they showed the body in three-quarters view as well as in profile; they produced light and shade by using thin or thick solutions of the glaze; they modeled the figures to show contours and depth, and the folds of feminine drapery. Corinth and Sicilian Gela were also centers of fine vase painting in this age, but no one questioned the superiority of the Athenians. It was not the competition of other potters that overcame the artists of the Ceramicus; it was the rise of a rival art of decoration. The vase painters tried to meet the attack by imitating the themes and styles of the muralists; but the taste of the age went against them, and slowly, as the fourth century advanced, pottery resigned itself to being more and more an industry, less and less an art.

Four stages vaguely divide the history of Greek painting. In the sixth century it is chiefly ceramic, devoted to the adornment of vases; in the fifth it is chiefly architectural, giving color to public buildings and statues; in the fourth it hovers between the domestic and the individual, decorating dwellings and making portraits; in the Hellenistic Age it is chiefly individual, producing easel pictures for private purchasers. Greek painting begins as an offshoot of drawing, and remains to the end a matter essentially of drawing and design. In its development it uses three methods: fresco, or painting upon wet plaster; tempera, or painting upon wet cloth or boards with colors mixed with the white of eggs; and encaustic, which mixed the colors with melted wax; this is as near as antiquity comes to painting in oils. Pliny, whose will to believe sometimes rivals that of Herodotus, assures us that the art of painting was already so advanced in the eighth century that Candaules, King of Lydia, paid its weight in gold for a picture by Bularchus;9 but all beginnings are mysteries. We may judge the high repute of painting in Greece from the fact that Pliny gives it more space than to sculpture; and apparently the great paintings of the classic and Hellenistic periods were as much discussed by the critics, and as highly regarded by the people, as the most distinguished specimens of architecture or statuary.10

Polygnotus of Thasos was as famous in fifth-century Greece as Ictinus or Pheidias. We find him in Athens about 472; perhaps it was the rich Cimon who procured him commissions to adorn several public buildings with murals.* Upon the Stoa, which thereafter was called Poecile, or the Painted Portico, and which, three centuries later, would give its name to the philosophy of Zeno, Polygnotus depicted the Sack of Troy—not the bloody massacre of the night of victory, but the somber silence of the morning after, with the victors quieted by the ruin around them, and the defeated lying calm in death. On the walls of the temple of the Dioscuri he painted the Rape of the Leucippidae, and set a precedent for his art by portraying the women in transparent drapery. The Amphictyonic Council was not shocked; it invited Polygnotus to Delphi, where, in the Lesche, or Lounge, he painted Odysseus in Hades, and another Sack of Troy. All these were vast frescoes, almost empty of landscape or background, but so crowded with individualized figures that many assistants were needed to fill in with color the master’s carefully drawn designs. The Lesche mural of Troy showed Menelaus’ crew about to spread sail for the return to Greece; in the center sat Helen; and though many other women were in the picture, all appeared to be gazing at her beauty. In a corner stood Andromache, with Astyanax at her breast; in another a little boy clung to an altar in fear; and in the distance a horse rolled around on the sandy beach.12 Here, half a century before Euripides, was all the drama of The Trojan Women. Polygnotus refused to take pay for these pictures, but gave them to Athens and Delphi out of the generosity of confident strength. All Hellas acclaimed him: Athens conferred citizenship upon him, and the Amphictyonic Council arranged that wherever he went in Greece he should be (as Socrates wished to be) maintained at the public expense.13 All that remains of him is a little pigment on a wall at Delphi to remind us that artistic immortality is a moment in geological time.

About 470 Delphi and Corinth established quadrennial contests in painting as part of the Pythian and Isthmian games. The art was now sufficiently advanced to enable Panaenus, brother (or nephew) of Pheidias, to make recognizable portraits of the Athenian and Persian generals in his Battle of Marathon. But it still placed all figures in one plane, and made them of one stature; it indicated distance not by a progressive diminution of size and a modeling with light and shade, but by covering more of the lower half of the farther figures with the curves that represented the ground. Towards 440 a vital step forward was taken. Agatharchus, employed by Aeschylus and Sophocles to paint scenery for their plays, perceived the connection between light and shade and distance, and wrote a treatise on perspective as a means of creating theatrical illusion. Anaxagoras and Democritus took up the idea from the scientific angle, and at the end of the century Apollodorus of Athens won the name of skiagraphos, or shadow painter, because he made pictures in chiaroscuro—i.e., in light and shade; hence Pliny spoke of him as “the first to paint objects as they really appeared.”14

Greek painters never made full use of these discoveries; just as Solon frowned upon the theatrical art as a deception, so the artists seem to have thought it against their honor, or beneath their dignity, to give to a plane surface the appearance of three dimensions. Nevertheless it was through perspective and chiaroscuro that Zeuxis, pupil of Apollodorus, made himself the supreme figure in fifth-century painting. He came from Heracleia (Pontica?) to Athens about 424; and even amid the noise of war his coming was considered an event. He was a “character,” bold and conceited, and he painted with a swashbuckling brush. At the Olympic games he strutted about in a checkered tunic on which his name was embroidered in gold; he could afford it, since he had already acquired “a vast amount of wealth” from his paintings.15 But he worked with the honest care of a great artist, and when Agatharchus boasted of his own speed of execution, Zeuxis said quietly, “I take a long time.”16 He gave away many of his masterpieces, on the ground that no price could do them justice; and cities and kings were happy to receive them.

He had only one rival in his generation—Parrhasius of Ephesus, almost as great and quite as vain. Parrhasius wore a golden crown on his head, called himself “the prince of painters,” and said that in him the art had reached perfection.17 He did it all in lusty good humor, singing as he painted.18 Gossip said that he had bought a slave and tortured him to study facial expression in pain for a picture of Prometheus;19 but people tell many stories about artists. Like Zeuxis he was a realist; his Runner was portrayed with such verisimilitude that those who beheld it expected the perspiration to fall from the picture, and the athlete to drop from exhaustion. He drew an immense mural of The People of Athens, representing them as implacable and merciful, proud and humble, fierce and timid, fickle and generous—and so faithfully that the Athenian public, we are informed, realized for the first time its own complex and contradictory character.20

A great rivalry brought him into public competition with Zeuxis. The latter painted some grapes so naturally that birds tried to eat them. The judges were enthusiastic about the picture, and Zeuxis, confident of victory, bade Parrhasius draw aside the curtain that concealed the Ephesian’s painting. But the curtain proved to be a part of the picture, and Zeuxis, having himself been deceived, handsomely acknowledged his defeat. Zeuxis suffered no loss of reputation. At Crotona he agreed to paint a Helen for the temple of Lacinian Hera, on condition that the five loveliest women of the city should pose in the nude for him, so that he might select from each her fairest feature, and combine them all in a second goddess of beauty.21 Penelope, too, found new life under his brush; but he admired more his portrait of an athlete, and wrote under it that men would find it easier to criticize him than to equal him. All Greece enjoyed his conceit, and talked about him as much as of any dramatist, statesmen, or general. Only the prize fighters outdid his fame.

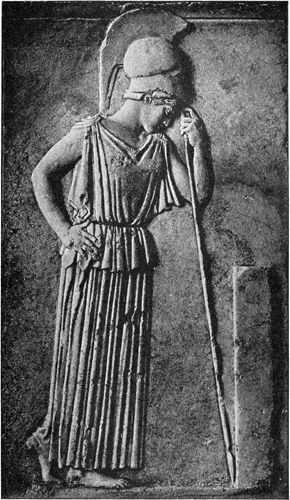

None the less painting remained slightly alien to the Greek genius, which loved form more than color, and made even the painting of the classic age (if we may judge it from hearsay) a statuesque study in line and design rather than a sensuous seizure of the colors of life. The Hellene delighted rather in sculpture: he filled his home, his temples, and his graves with terracotta statuettes, worshiped his gods with images of stone, and marked the tombs of his departed with stelae reliefs that are among the commonest and most moving products of Greek art. The artisans of the stelae were simple workers who carved by rote, and repeated a thousand times the familiar theme of the quiet parting, with clasped hands, of the living from the dead. But the theme itself is noble enough to bear repetition, for it shows classic restraint at its best, and teaches even a romantic soul that feeling speaks with most power when it lowers its voice. These slabs show us the dead most often in some characteristic occupation of life—a child playing with a hoop, a girl carrying a jar, a warrior proud in his armor, a young woman admiring her jewels, a boy reading a book while his dog lies content but watchful under his chair. Death in these stelae is made natural, and therefore forgivable.

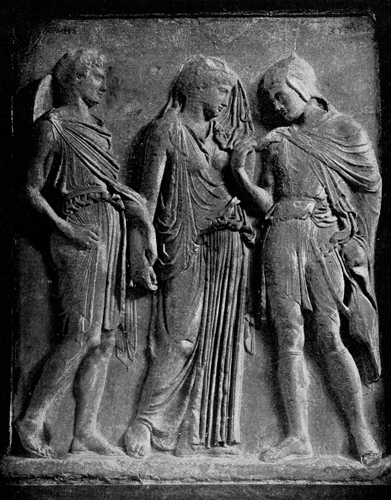

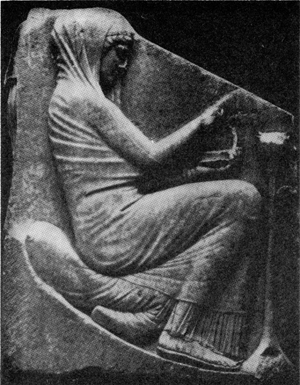

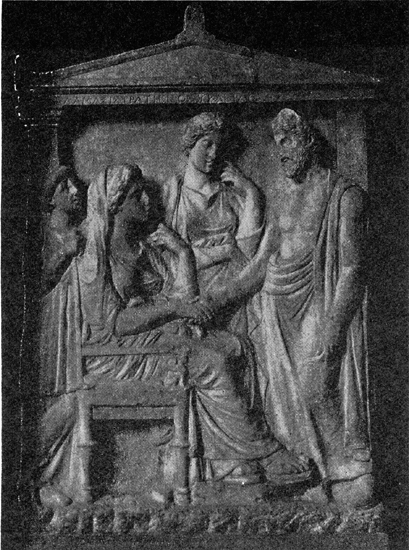

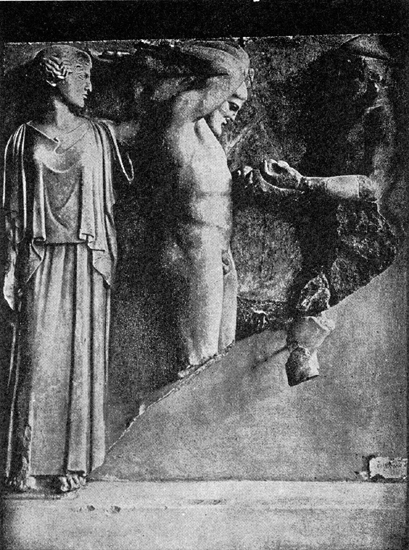

More complex, and supreme in their kind, are the sculptural reliefs of this age. In one of them Orpheus bids a lingering farewell to Eurydice, whom Hermes has reclaimed for the nether world;22 in another Demeter gives to Triptolemus the golden grain by which he is to establish agriculture in Greece; here some of the coloring still adheres to the stone, and suggests the warmth and brilliance of Greek relief in the Golden Age.23 Still more beautiful is The Birth of Aphrodite, carved on one side of the “Ludovisi Throne”* by an unknown sculptor of presumably Ionian training. Two goddesses are raising Aphrodite from the sea; her thin wet garment clings to her form and reveals it in all the splendor of maturity; the head is semi-Asiatic, but the drapery of the attendant deities, and the soft grace of their pose, bear the stamp of the sensitive Greek eye and hand. On another side of the “throne” a nude girl plays the double flute. On a third side a veiled woman prepares her lamp for the evening; perhaps the face and garments here are even nearer to perfection than on the central piece.

The advance of the fifth-century sculptor upon his forebears is impressive. Frontality is abandoned, foreshortening deepens perspective, stillness gives place to movement, rigidity to life. Indeed, when Greek statuary breaks through the old conventions and shows man in action, it is an artistic revolution; rarely before, in Egypt or the Near East, or in pre-Marathon Greece, has any sculpture in the round been caught in action. These developments owe much to the freshened vitality and buoyancy of Greek life after Salamis, and more to the patient study of motile anatomy by master and apprentice through many generations. “Is it not by modeling your works on living beings,” asks Socrates, sculptor and philosopher, “that you make your statues appear alive? . . . And as our different attitudes cause the play of certain muscles of our body, upwards or downwards, so that some are contracted and some stretched, some wrung and some relaxed, is it not by expressing these efforts that you give greater truth and verisimilitude to your works?”24 The Periclean sculptor is interested in every feature of the body—in the abdomen as much as the face, in the marvelous play of the elastic flesh over the moving framework of the bones, in the swelling of muscles, tendons, and veins, in the endless wonders of the structure and action of hands and ears and feet; and he is fascinated by the difficulty of molding the extremities. He does not often use models to pose for him in a studio; for the most part he is content to watch the men stripped and active in the palaestra or on the athletic field, and the women solemnly marching in the religious processions, or naturally absorbed in their domestic tasks. It is for this reason, and not through modesty, that he centers his studies of anatomy upon the male, and in his portraits of women substitutes the refinements of drapery for anatomical detail—though he makes the drapery as transparent as he dares. Tired of the stiff skirts of Egypt and archaic Greece he loves to show feminine robes agitated by a breeze, for here again he catches the quality of motion and life.

He uses almost any workable material that comes to his hand—wood, ivory, bone, terra cotta, limestone, marble, silver, gold; sometimes, as in the chryselephantine statues of Pheidias, he uses gold on the raiment and ivory for the flesh. In the Peloponnesus bronze is the sculptor’s favorite material, for he admires its dark tints as well adapted to represent the bodies of men tanned by nudity under the sun; and—not knowing the rapacity of man—he dreams that it is more durable than stone. In Ionia and Attica he prefers marble; its difficulty stimulates him, its firmness lets him chisel it safely, its translucent smoothness seems designed to convey the rosy color and delicate texture of a woman’s skin. Near Athens the sculptor discovers the marble of Mt. Pentelicus, and observes how its iron content mellows with time and weather into a vein of gold glowing through the stone; and with the obstinate patience that is half of genius he slowly carves the quarries into living statuary. When he works in bronze the fifth-century sculptor uses the method of hollow casting by the process of cire perdu, or lost wax: i.e., he makes a model in plaster or clay, overlaps it with a thin coat of “wax, covers it all with a mold of plaster or clay perforated at many points, and places the figure in a furnace whose heat melts the wax, which runs out through the holes; then he pours molten bronze into the mold at the top till the metal fills all the space before occupied by the wax; he cools the figure, removes the outer mold, and files and polishes, lacquers or paints or gilds, the bronze into the final form. If he prefers marble he begins with the unshaped block, unaided by any system of pointing;* he works freehand, and for the most part guides himself by the eye instead of by instruments;25 blow by blow he removes the superfluous until the perfection that he has conceived takes shape in the stone, and, in Aristotle’s phrase, matter becomes form.

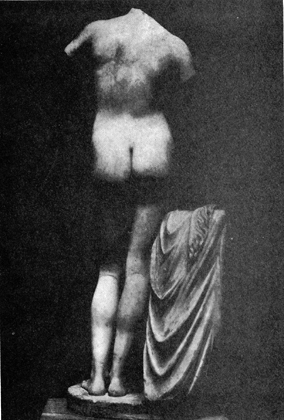

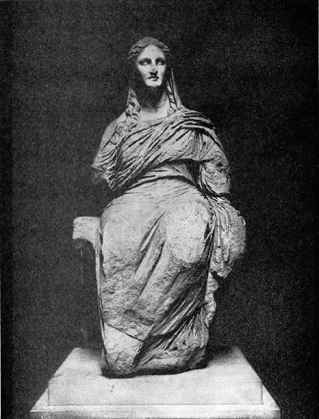

His subjects range from gods to animals, but they must all be physically admirable; he has no use for weaklings, for intellectuals, for abnormal types, or for old women or men. He does well with the horse, but indifferently with other animals. He does better with women, and some of his anonymous masterpieces, like the meditative young lady holding her robe on her breast in the Athens Museum, achieve a quiet loveliness that does not lend itself to words. He is at his best with athletes, for these he admires without stint, and can observe without hindrance; now and then he exaggerates their prowess, and crosses their abdomens with incredible muscles; but despite this fault he can cast bronzes like that found in the sea near Anticythera, and alternatively named an Ephebos, or a Perseus whose hand once held Medusa’s snake-haired head. Sometimes he catches a youth or a girl absorbed in some simple and spontaneous action, like the boy drawing a thorn from his foot.* But his country’s mythology is still the leading inspiration of his art. That terrible conflict between philosophy and religion which runs through the thought of the fifth century does not show yet on the monuments; here the gods are still supreme; and if they are dying they are nobly transmuted into the poetry of art. Does the sculptor who shapes in bronze the powerful Zeus of Artemisium† really believe that he is modeling the Law of the World? Does the artist who carves the gentle and sorrowful Dionysus of the Delphi Museum know, in the depths of his inarticulate understanding, that Dionysus has been shot down by the arrows of philosophy, and that the traditional features of Dionysus’ successor, Christ, are already previsioned in this head?

If Greek sculpture achieved so much in the fifth century, it was in part because each sculptor belonged to a school, and had his place in a long lineage of masters and pupils carrying on the skills of their art, checking the extravagances of independent individualities, encouraging their specific abilities, disciplining them with a sturdy grounding in the technology and achievements of the past, and forming them, through this interplay of talent and law, into a greater art than often comes to genius isolated and unruled. Great artists are more frequently the culmination of a tradition than its overthrow; and though rebels are the necessary variants in the natural history of art, it is only when their new line has been steadied with heredity and chastened with time that it generates supreme personalities.

Five schools performed this function in Periclean Greece: those of Rhegium, Sicyon, Argos, Aegina, and Attica. About 496 another Pythagoras of Samos settled at Rhegium, cast a Philoctetes that won him Mediterranean fame, and put into the faces of his statues such signs of passion, pain, and age as shocked all Greek sculptors till those of the Hellenistic period decided to imitate him. At Sicyon Canachus and his brother Aristocles carried on the work begun a century earlier by Dipoenus and Scyllis of Crete-Callon and Onatas brought distinction to Aegina by their skill with bronze; perhaps it was they who made the Aegina pediments. At Argos Ageladas organized the transmission of sculptural technique in a school that reached its apex in Polycleitus.

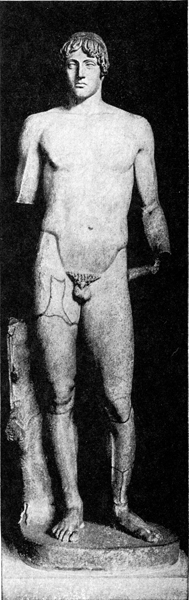

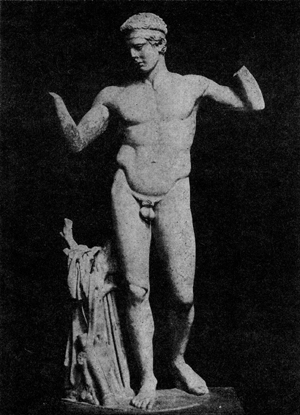

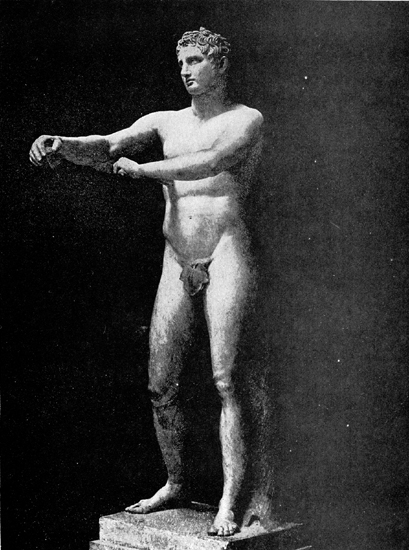

Coming from Sicyon, Polycleitus made himself popular in Argos by designing for its temple of Hera, about 422, a gold and ivory statue of the matron goddess, which the age ranked second only to the chryselephantine immensities of Pheidias.* At Ephesus he joined in a competition with Pheidias, Cresilas, and Phradmon to make an Amazon for the temple of Artemis; the four artists were made judges of the result; each, the story goes, named his own work best, Polycleitus’ second best; and the prize was given to the Sicyonian.†27 But Polycleitus loved athletes more than women or gods. In the famous Diadumenos (of which the best surviving copy is in the Athens Museum) he chose for representation that moment in which the victor binds about his head the fillet over which the judges are to place the laurel wreath. The chest and abdomen are too muscular for belief, but the body is vividly posed upon one foot, and the features are a definition of classic regularity. Regularity was the fetish of Polycleitus; it was his life aim to find and establish a canon or rule for the correct proportion of every part in a statue; he was the Pythagoras of sculpture, seeking a divine mathematics of symmetry and form. The dimensions of any part of a perfect body, he thought, should bear a given ratio to the dimensions of any one part, say the index finger. The Polycleitan canon called for a round head, broad shoulders, stocky torso, wide hips, and short legs, making all in all a figure rather of strength than of grace. The sculptor was so fond of his canon that he wrote a treatise to expound it, and molded a statue to illustrate it. Probably this was the Doryphoros, or Spear Bearer, of which the Naples Museum has a Roman copy; here again is the brachycephalic head, the powerful shoulders, the short trunk, the corrugated musculature overflowing the groin. Lovelier is the Westmacott Ephebos of the British Museum, where the lad has feelings as well as muscles, and seems lost in a gentle meditation on something else than his own strength. Through these figures the canon of Polycleitus became for a time a law to the sculptors of the Peloponnesus; it influenced even Pheidias, and ruled till Praxiteles overthrew it with that rival canon of tall, slim elegance which survived through Rome into the statuary of Christian Europe.

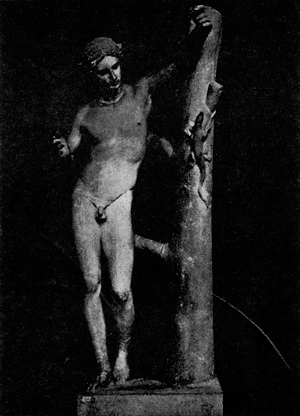

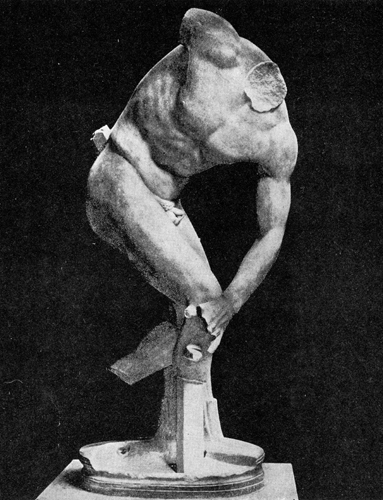

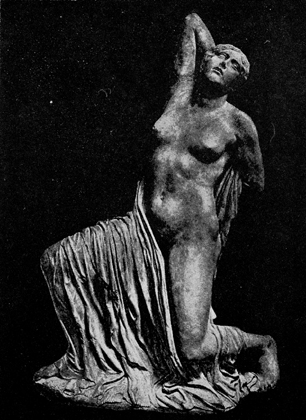

Myron mediated between the Peloponnesian and the Attic schools. Born at Eleutherae, living at Athens, and (says Pliny28) studying for a while with Ageladas, he learned to unite Peloponnesian masculinity with Ionian grace. What he added to all the schools was motion: he saw the athlete not, like Polycleitus, before or after the contest, but in it; and realized his vision so well in bronze that no other sculptor in history has rivaled him in portraying the male body in action. About 470 he cast the most famous of athletic statues—the Discobolos or Discus Thrower.* The wonder of the male frame is here complete: the body carefully studied in all those movements of muscle, tendon, and bone that are involved in the action; the legs and arms and trunk bent to give the fullest force to the throw; the face not distorted with effort, but calm in the confidence of ability; the head not heavy or brutal, but that of a man of blood and refinement, who could write books if he would condescend. This chef-d’oeuvre was only one of Myron’s achievements; his contemporaries valued it, but ranked even more highly his Athena and Marsyas† and his Ladas. Athena here is too lovely for the purpose; no one could guess that this demure virgin is watching with calm content the flaying of the defeated flutist. Myron’s Marsyas is George Bernard Shaw caught in an unseemly but eloquent pose; he has played for the last time, and is about to die; but he will not die without a speech. Ladas was an athlete who succumbed to the exhaustion of victory; Myron portrayed him so realistically that an old Greek, seeing the statue, cried out: “Like as thou wert in life, O Ladas, breathing forth thy panting soul, such hath Myron wrought thee in bronze, stamping on all thy body thine eagerness for the victor’s crown.” And of Myron’s Heifer the Greeks said that it could do everything but moo.29

The Attic or Athenian school added to the Peloponnesians and to Myron what woman gives to man—beauty, tenderness, delicacy, and grace; and because in doing this it still retained a masculine element of strength, it reached a height that sculpture may never attain again. Calamis was still a little archaic, and Nesiotes and Critius, in casting a second group of Tyrannicides, did not free themselves from the rigid simplicity of the sixth century; Lucian warns orators not to behave like such lifeless figures. But when, about 423, Paeonius of Thracian Mende, after studying sculpture at Athens, made for the Messenians a Nike, or Victory, he touched heights of grace and loveliness that no Greek would reach again until Praxiteles; and not even Praxiteles would surpass the flow of this drapery, or the ecstasy of this motion.*

From 447 to 438 Pheidias and his aides were absorbed in carving the statues and reliefs of the Parthenon. As Plato was first a dramatist and then became a dramatic philosopher, so Pheidias was first a painter and then became a pictorial sculptor. He was the son of a painter, and studied for a while under Polygnotus; from him, presumably, he learned design and composition, and the grouping of figures for a total effect; from him, it may be, he acquired that “grand style” which made him the greatest sculptor in Greece. But painting did not satisfy him; he needed more dimensions. He took up sculpture, and perhaps studied the bronze technique of Ageladas. Patiently he made himself master of every branch of his art.

He was already an old man when, about 438, he formed his Athene Parthenos, for he depicted himself on its shield as aged and bald, and not unacquainted with grief. No one expected him to carve with his own hands the hundreds of figures that filled the metopes, frieze, and pediments of the Parthenon; it was enough that he superintended all Periclean building, and designed the sculptural ornament; he left it to his pupils, above all to Alcamenes, to execute the plans. He himself, however, made three statues of the city’s goddess for the Acropolis. One was commissioned by Athenian colonists in Lemnos; it was of bronze, a little larger than life, and so delicately molded that Greek critics considered this Lemnian Athena the most beautiful of Pheidias’ works.*30 Another was the Athene Promachos, a colossal bronze representation of the goddess as the warlike defender of her city; it stood between the Propylaea and the Erechtheum, rose with its pedestal to a height of seventy feet, and served as a beacon to mariners and a warning to enemies.† The most famous of the three, the Athene Parthenos, stood thirty-eight feet high in the interior of the Parthenon, as the virgin goddess of wisdom and chastity. For this culminating figure Pheidias wished to use marble, but the people would having nothing less than ivory and gold. The artist used ivory for the visible body, and forty-four talents (2545 lbs.) of gold for the robe;32 furthermore, he adorned it with precious metals, and elaborate reliefs on the helmet, the sandals, and the shield. It was so placed that on Athena’s feast day the sun would shine through the great doors of the temple directly upon the brilliant drapery and pallid face of the Virgin.‡

The completion of the work brought no happiness to Pheidias, for some of the gold and ivory assigned to him for the statue disappeared from his studio and could not be accounted for. The foes of Pericles did not overlook this opportunity. They charged Pheidias with theft, and convicted him.§ But the people of Olympia interceded for him, and paid his bail of forty (?) talents, on condition that he come to Olympia and make a chryselephantine statue for the temple of Zeus;34 they were glad to trust him with more ivory and gold. A special workshop was built for him and his assistants near the temple precincts, and his brother Panaenus was commissioned to decorate the throne of the statue and the walls of the temple with paintings.35 Pheidias was enamored of size, and made his seated Zeus sixty feet high, so that when it was placed within the temple critics complained that the god would break through the roof if he should take it into his head to stand up. On the “dark brows” and “ambrosial locks”36 of the Thunderer, Pheidias placed a crown of gold in the form of olive branches and leaves; in the right hand he set a small statue of Victory, also in ivory and gold; in the left hand a scepter inlaid with precious stones; on the body a golden robe engraved with flowers; and on the feet sandals of solid gold. The throne was of gold, ebony, and ivory; at its base were smaller statues of Victory, Apollo, Artemis, Niobe, and Theban lads kidnaped by the Sphinx.37 The final result was so impressive that legend grew around it: when Pheidias had finished, we are told, he begged for a sign from heaven in approval; whereupon a bolt of lightning struck the pavement near the statue’s base—a sign which, like most celestial messages, admitted of diverse interpretations.* The work was listed among the Seven Wonders of the World, and all who could afford it made a pilgrimage to see the incarnate god. Aemilius Paullus, the Roman who conquered Greece, was struck with awe on seeing the colossus; his expectations, he confessed, had been exceeded by the reality.38 Dio Chrysostom called it the most beautiful image on earth, and added, as Beethoven was to say of Beethoven’s music: “If one who is heavyladen in mind, who has drained the cup of misfortune and sorrow in life, and whom sweet sleep visits no more, were to stand before this image, he would forget all the griefs and troubles that befall the life of man.”39 “The beauty of the statue,” said Quintilian, “even made some addition to the received religion; the majesty of the work was equal to the god.”40

Of Pheidias’ last years there is no unchallenged account. One story pictures him as returning to Athens and dying in jail;41 another lets him stay in Elis, only to have Elis put him to death in 432;42 there is not much to choose between these denouements. His pupils carried on his work, and attested his success as a teacher by almost equaling him. Agoracritus, his favorite, carved a famous Nemesis; Alcamenes made an Aphrodite of the Gardens which Lucian ranked with the highest masterpieces of statuary,†43 The school of Pheidias came to an end with the fifth century, but it left Greek sculpture considerably further advanced than it had found it. Through Pheidias and his followers the art had neared perfection at the very moment when the Peloponnesian War began the ruin of Athens. Technique had been mastered, anatomy was understood, life and movement and grace had been poured into bronze and stone. But the characteristic achievement of Pheidias was the attainment and definitive expression of the classic style, the “grand style” of Winckelmann: strength reconciled with beauty, feeling with restraint, motion with repose, flesh and bone with mind and soul. Here, after five centuries of effort, the famed “serenity” so imaginatively ascribed to the Greeks was at least conceived; and the passionate and turbulent Athenians, contemplating the figures of Pheidias, might see how nearly, if only in creative sculptury, men for a moment had been like gods.

During the fifth century the Doric order consolidated its conquest of Greece. Among all the Greek temples built in this prosperous age only a few Ionic shrines survive, chiefly the Erechtheum and the temple of Nike Apteros on the Acropolis. Attica remained faithful to Doric, yielding to the Ionic order only so far as to use it for the inner columns of the Propylaea, and to place a frieze around the Theseum and the Parthenon; perhaps a tendency to make the Doric column longer and slenderer reveals a further influence of the Ionic style. In Asia Minor the Greeks imbibed the Oriental love of delicate ornament, and expressed it in the complex elaboration of the Ionic entablature, and the creation of a new and more ornate order, the Corinthian. About 430 (as Vitruvius tells the tale) an Ionian sculptor, Callimachus, was struck by the sight of a basket of votive offerings, covered with a tile, which a nurse had left upon the tomb of her mistress; a wild acanthus had grown around the basket and the tile; and the sculptor, pleased with the natural form so suggested, modified the Ionic capitals of a temple that he was building at Corinth, by mingling acanthus leaves with the volutes.44 Probably the story is a myth, and the nurse’s basket had less influence than the palm and papyrus capitals of Egypt in generating the Corinthian style. The new order made little headway in classic Greece; Ictinus used it for one isolated column in the court of an Ionic temple at Phigalea, and towards the end of the fourth century it was used for the choragic monument of Lysicrates. Only under the elegant Romans of the Empire did this delicate style reach its full development.

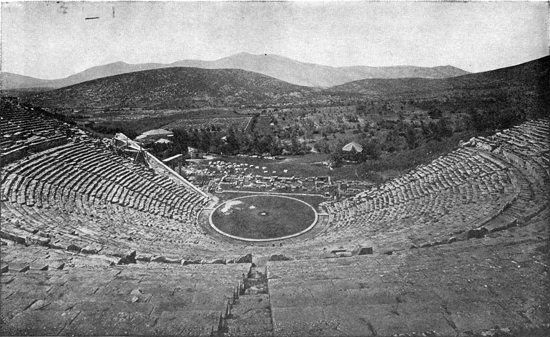

All the Greek world was building temples in this period. Cities almost bankrupted themselves in rivalry to have the fairest statuary and the largest shrines. To her massive sixth-century edifices at Samos and Ephesus Ionia added new Ionic temples at Magnesia, Teos, and Priene. At Assus in the Troad Greek colonists raised an almost archaic Doric fane to Athena. At the other end of Hellas Crotona built, about 480, a vast Doric home for Hera; it survived till 1600, when a bishop thought he could make better use of its stones.45 To the fifth century belong the greatest of the temples at Poseidonia (Paestum), Segesta, Selinus, and Acragas, and the temple of Asclepius at Epidaurus. At Syracuse the columns still stand of a temple raised to Athena by Gelon I, and partly preserved by its transformation into a Christian church, At Bassae, near Phigalea in the Peloponnesus, Ictinus designed a temple of Apollo strangely different from his other masterpiece, the Parthenon; here the Doric periptery enclosed a space occupied by a small naos and a large open court surrounded by an Ionic colonnade; and around the interior of this court, along the inner face of the Ionic columns, ran a frieze almost as graceful as the Parthenon’s, and having the added virtue of being visible.*

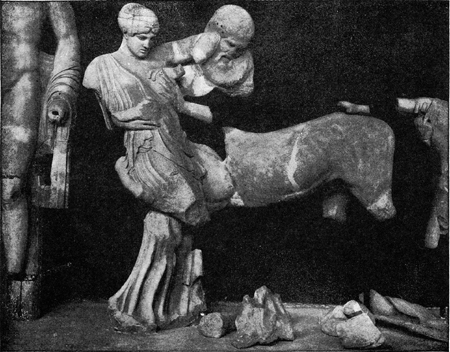

At Olympia the Elian architect Libon, a generation before the Parthenon, raised a rival to it in a Doric shrine to Zeus. Six columns stood at each end, thirteen on either side; perhaps too stout for beauty, and unfortunate in their material—a coarse limestone coated with stucco; the roof, however, was of Pentelic tiles. Paeonius and Alcamenes, Pausanias tells us,46 carved for the pediments powerful figures† portraying on the eastern gable the chariot race between Pelops and Oenomaus, and on the western gable the struggle of Lapiths and centaurs. The Lapiths, in Greek legend, were a mountain tribe of Thessaly. When Pirithous, their king, married Hippodameia, daughter of King Oenomaus of Pisa in Elis, he invited the centaurs to the wedding feast. The centaurs dwelt in the mountains about Pelion; Greek art represented them as half man and half horse, possibly to suggest their untamed woodland nature, or because the centaurs were such excellent horsemen that each man and his mount seemed to be one animal. At the feast these horsemen got drunk, and tried to carry off the Lapith women. The Lapiths fought bravely for their ladies, and won. (Greek art never tired of this story, and perhaps used it to symbolize the clearing of the wilderness from wild beasts, and the struggle between the human and the bestial in man.) The figures on the east pediment are archaically stiff and still; those on the west seem hardly of the same period, for though some of them are crude, and the hair is stylized in ancient fashion, they are alive with action, and show a mature grasp of sculptural grouping. Startlingly beautiful is the bride, a woman of no fragile slenderness, but of a full-bodied loveliness that quite explains the war. A bearded centaur has one arm around her waist, one hand upon her breast; she is about to be snatched from her nuptials, and yet the artist portrays her features in such calm repose that one suspects him of having read Lessing or Winckelmann; or perhaps, like any woman, she is not insensitive to the compliment of desire. Less ambitious and massive, but more delicately finished, are the extant metopes of the temple, recounting certain labors of Heracles; one, wherein Heracles holds up the world for Atlas, stands out as a work of complete mastery. Heracles here is no abnormal giant, rock-ribbed with musculature, but simply a man of full and harmonious development. Before him is Atlas, whose head would adorn the shoulders of Plato. At the left is one of Atlas’ daughters, perfect in the natural beauty of healthy womanhood; perhaps the artist had some symbolism in mind when he showed her gently helping the strong man to bear the weight of the world. The specialist finds some faults of execution and detail in these half-ruined metopes; but to an amateur observer the bride, and Heracles, and the daughter of Atlas, are as near to perfection as anything in the history of sculptural relief.

Attica leads all Greece in the abundance and excellence of its fifth-century building. Here the Doric style, which tends elsewhere to a bulging corpulence, takes on Ionian grace and elegance; color is added to line, ornament to symmetry. On a dangerous headland at Sunium those who risked the sea raised to Poseidon a shrine of which eleven columns stand. At Eleusis Ictinus designed a spacious temple to Demeter, and under Pericles’ persuasion Athens contributed funds to make this edifice worthy of the Eleusinian festival. At Athens the proximity of good marble on Mt. Pentelicus and in Paros encouraged the artist with the finest of building materials. Seldom, until our periods of economic breakdown, has a democracy been able or willing to spend so lavishly on public construction. The Parthenon cost seven hundred talents ($4,200,000); the Athene Parthenos (which, however, was a gold reserve as well as a statue) cost $6,000,000; the unfinished Propylaea, $2,400,000; minor Periclean structures at Athens and the Piraeus, $18,000,000; sculpture and other decoration, $16,200,000; altogether, in the sixteen years from 447 to 431, the city of Athens voted $57,600,000 for public buildings, statuary, and painting.47 The spread of this sum among artisans and artists, executives and slaves, had much to do with the prosperity of Athens under Pericles.

Imagination can picture vaguely the background of this courageous adventure in art. The Athenians, on their return from Salamis, found their city almost wholly devastated by the Persian occupation; every edifice of any value had been burned to the ground. Such a calamity when it does not destroy the citizens as well as the city, makes them stronger; the “act of God” clears away many eyesores and unfit habitations; chance accomplishes what human obstinacy would never allow; and if food can be found through the crisis, the labor and genius of men create a finer city than before. The Athenians, even after the war with Persia, were rich in both labor and genius, and the spirit of victory doubled their will for great enterprise. In a generation Athens was rebuilt; a new council chamber rose, a new prytaneum, new homes, new porticoes, new walls of defense, new wharves and warehouses at a new port. About 446 Hippodamus of Miletus, chief town-planner of antiquity, laid out a new Piraeus, and set a new style, by replacing the old chaos of haphazard and winding alleys with broad, straight streets crossing at right angles. On an elevation a mile northwest of the Acropolis unknown artists raised that smaller Parthenon known as the Theseum, or temple of Theseus.* Sculptors filled the pediments with statuary and the metopes with reliefs, and ran a frieze above the inner columns at both ends. Painters colored the moldings, the triglyphs, metopes, and frieze, and made bright murals for an interior dimly lit by light shining through marble tiles.†

The finest work of Pericles’ builders was reserved for the Acropolis, the ancient seat of the city’s government and faith. Themistocles began its reconstruction, and planned a temple one hundred feet long, known therefore as the Hecatompedon. After his fall the work was abandoned; the oligarchic party opposed it on the ground that any dwelling for Athena, if it was not to bring bad luck to Athens, must be built upon the site of the old temple of Athene Polias (i.e., Athena of the City), which the Persians had destroyed. Pericles, caring nothing about superstitions, adopted the site of the Hecatompedon for the Parthenon, and, though the priests protested to the end, went on with his plans. On the southwestern slope of the Acropolis his artists erected an Odeum, or Music Hall, unique in Athens for its cone-shaped dome. It offered a handle to conservative satirists, who thenceforth referred to Pericles’ conical head as his odeion, or hall of song. The Odeum was built for the most part of wood, and soon succumbed to time. In this auditorium musical performances were presented, and the Dionysian dramas were rehearsed; and there, annually, were held the contests instituted by Pericles in vocal and instrumental music. The versatile statesman himself often acted as a judge in these competitions.

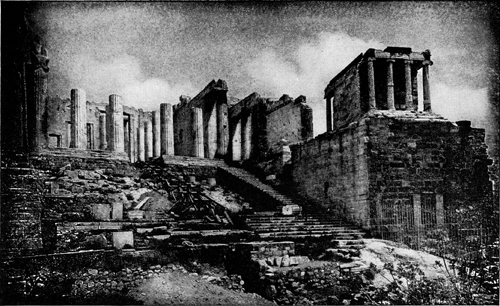

The road to the summit, in classical days, was devious and gradual, and was flanked with statues and votive offerings. Near the top was a majestically broad flight of marble steps, buttressed with bastions on either side. On the south bastion Callicrates raised a miniature Ionic temple to Athena as Nike Apteros, or the Wingless Victory.* Elegant reliefs (partly preserved in the Athens Museum) adorned the external balustrade with figures of winged Victories bringing to Athens their far-gathered spoils. These Nikai are in the noblest style of Pheidias, less vigorous than the massive goddesses of the Parthenon, but even more graceful in motion, and more delicate and natural in their protrayal of drapery. The Victory tying her sandals deserves her name, for she is one of the triumphs of Greek art.

At the top of the Acropolis steps Mnesicles built, in elaboration of Mycenaean pylons, an entrance with five openings, before each of which stood a Doric portico; these colonnades in time gave to the whole edifice their name of Propylaea, or Before the Gates. Each portico carried a frieze of triglyphs and metopes, and was crowned with a pediment. Within the passageway was an Ionic colonnade, boldly inserted within a Doric form. The interior of the northern wing was decorated with paintings by Polygnotus and others, and contained votive tablets (pinakes) of terra cotta or marble; hence its name of Pinakotheka, or Hall of Tablets. A small south wing remained unfinished; war, or the reaction against Pericles, put a stop to the work, and left an ungainly mass of beautiful parts as a gateway to the Parthenon.

Within these gates, on the left, was the strangely Oriental Erechtheum. This, too, was overtaken by war: not more than half of it was finished when the disaster of Aegospotami reduced Athens to chaos and poverty. It was begun after Pericles’ death, under the prodding of conservatives who feared that the ancient heroes Erechtheus and Cecrops, as well as the Athena of the older shrine, and the sacred snakes that haunted the spot, would punish Athens for building the Parthenon on another site. The varied purposes of the structure determined its design, and destroyed its unity. One wing was dedicated to Athene Polias, and housed her ancient image; another was devoted to Erechtheus and Poseidon. The naos or cella, instead of being enclosed by a unifying peristyle, was here buttressed with three separate porticoes. The northern and eastern porches were upheld by slender Ionic columns as beautiful as any of their kind.* In the northern porch was a perfect portal, adorned with a molding of marble flowers. In the cella was the primitive wooden statue of Athena, which the pious believed had fallen from heaven; there, too, was the great lamp whose fire was never extinguished, and which Callimachus, the Cellini of his time, had fashioned of gold and embellished with acanthus leaves, like his Corinthian capitals. The south portico was the famous Porch of the Maidens, or Caryatids.† These patient women were descended, presumably, from the basket bearers of the Orient; and an early caryatid at Tralles, in Asia Minor, betrays the Easternprobably the Assyrian—origin of the form. The drapery is superb, and the natural flexure of the knee gives an impression of ease; but even these substantial ladies seem hardly strong enough to convey that sense of sturdy and reliable support which the finest architecture gives. It was an aberration of taste that Pheidias would probably have forbidden.

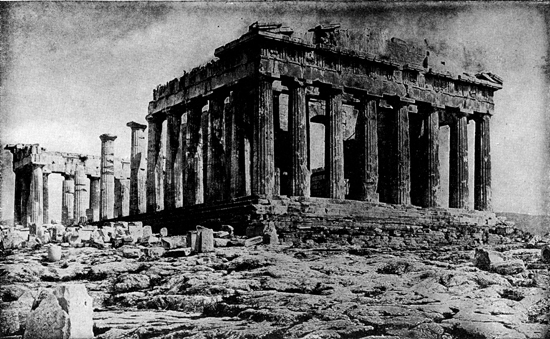

In 447 Ictinus, aided by Callicrates, and under the general supervision of Pheidias and Pericles, began to build a new temple for Athene Parthenos. In the western end of the structure he placed a room for her maiden priestesses, and called it the room “of the virgins”—ton parthenon; and in the course of careless time this name of a part, by a kind of architectural metaphor, was applied to the whole. Ictinus chose as his material the white marble of Mt. Pentelicus, veined with iron grains. No mortar was used; the blocks were so accurately squared and so finely finished that each stone grasped the next as if the two were one. The column drums were bored to let a small cylinder of olivewood connect them, and permit each drum to be turned around and around upon the one below it until the meeting surfaces were ground so smooth that the division between drums was almost invisible.49

The style was pure Doric, and of classic simplicity. The design was rectangular, for the Greeks did not care for circular or conical forms; hence there were no arches in Greek architecture, though Greek architects must have been familiar with them. The dimensions were modest: 228 × 101 × 65 feet. Probably a system of proportion, like the Polycleitan canon, prevailed in every part of the building, all measurements bearing a given relation to the diameter of the column.50 At Poseidonia the height of the column was four times its diameter; here it was five; and the new form mediated successfully between Spartan sturdiness and Attic elegance. Each column swelled slightly (three quarters of an inch in diameter) from base to middle, tapered toward the top, and leaned toward the center of its colonnade; each corner column was a trifle thicker than the rest. Every horizontal line of stylobate and entablature was curved upward towards its center, so that the eye placed at one end of any supposedly level line could not see the farther half of the line. The metopes were not quite square, but were designed to appear square from below. All these curvatures were subtle corrections for optical illusions that would otherwise have made stylobate lines seem to sink in the center, columns to diminish upward from the base, and corner columns to be thinner and outwardly inclined. Such adjustments required considerable knowledge of mathematics and optics, and constituted but one of those mechanical features that made the temple a perfect union of science and art. In the Parthenon, as in current physics, every straight line was a curve, and, as in a painting, every part was drawn toward the center in subtle composition. The result was a certain flexibility and grace that seemed to give life and freedom to the stones.

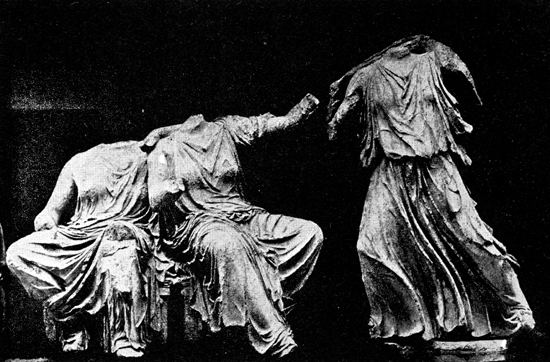

Above the plain architrave ran an alternating series of triglyphs and metopes. In the ninety-two metopes were high reliefs recounting once more the struggle of “civilization” against “savagery” in the wars of Greeks and Trojans, Greeks and Amazons, Lapiths and centaurs, giants and gods. These slabs are clearly the work of many hands and unequal skills; they do not match in excellence the reliefs of the cella frieze, though some of the centaur heads are Rembrandts in stone. In the gable pediments were statuary groups carved in the round and in heroic size. In the east pediment, over the entrance, the spectator was allowed to see the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus. Here was a powerful recumbent “Theseus,”* a giant capable of philosophical meditation and civilized repose; and a fine figure of Iris, the female Hermes, with drapery clinging and yet blown by the wind—for Pheidias considers it an ill wind that does not disturb some robe. Here also was a majestic “Hebe,” the goddess of youth, who filled the cups of the Olympians with nectar; and here were three imposing “Fates.” In the left corner four horses’ heads—eyes flashing, nostrils snorting, mouths foaming with speed—announced the rising of the sun, while in the right corner the moon drove her chariot to her setting; these eight are the finest horses in sculptural history. In the west pediment Athena contested with Poseidon the lordship of Attica. Here again were horses, as if to redeem the forked absurdity of man; and reclining figures that represented, with unrealistic magnificence, Athens’ modest streams. Perhaps the male figures are too muscular, and the female too spacious; but seldom has statuary been grouped so naturally, or so skillfully adjusted to the narrowing spaces of a pediment. “All other statues,” said Canova, with some hyperbole, “are of stone; these are of flesh and blood.”

More attractive, however, are the men and women of the frieze. For 525 feet along the top of the outer wall of the cella, within the portico, ran this most famous of all reliefs. Here, presumably, the youths and maids of Attica are bearing homage and gifts to Athena on the festival day of the Panathenaic games. One part of the procession moves along the west and north sides, another along the south side, to meet on the east front before the, goddess, who proudly offers to Zeus and other Olympians the hospitality of her city and a share of her spoils. Handsome knights move in graceful dignity on still handsomer steeds; chariots support dignitaries, while simple folk are happy to join in on foot; pretty girls and quiet old men carry olive branches and trays of cakes; attendants bear on their shoulders jugs of sacred wine; stately women convey to the goddess the peplos that they have woven and embroidered for her in long anticipation of this holy day; sacrificial victims move with bovine patience or angry prescience to their fate; maidens of high degree bring utensils of ritual and sacrifice; and musicians play on their flutes deathless ditties of no tone. Seldom have animals or men been honored with such painstaking art. With but two and a quarter inches of relief the sculptors were able, by shading and modeling, to achieve such an illusion of depth that one horse or horseman seems to be beyond another, though the nearest is raised no farther from the background than the rest.51 Perhaps it was a mistake to place this extraordinary relief so high that men could not comfortably contemplate it, or exhaust its excellence. Pheidias excused himself, doubtless with a twinkle in his eye, on the ground that the gods could see it; but the gods were dying while he carved.

FIG. 1—Hygiaea, Goddess of Health

Athens Museum

(See page 499)

FIG. 2—The Cup-Bearer

From the Palace of Minos.

Heracleum Museum

(See page 20)

FIG. 3—The “Snake Goddess”

Boston Museum

(See page 17)

FIG. 4—Wall Fresco and “Throne of Minos”

Heracleum Museum

(See page 18)

FIG. 5—A Cup from Vaphio

Athens Museum

(See page 32)

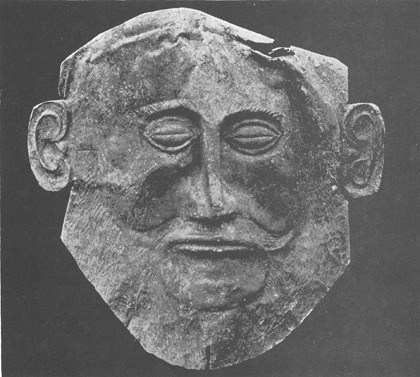

FIG. 6—Mask of “Agamemnon”

Athens Museum

(See page 32)

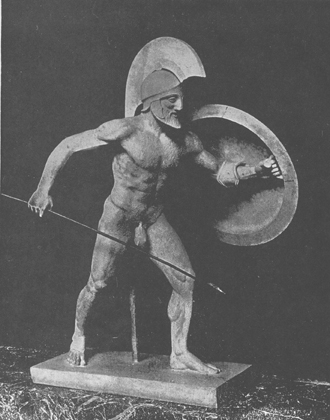

FIG. 7—Warrior, from temple of Aphaea at Aegina

Munich Glyptothek

(See page 95)

(See page 96)

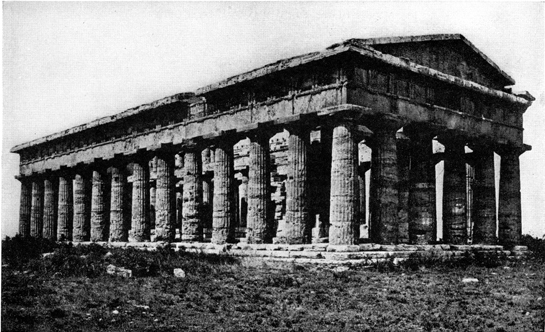

FIG. 9—Temple of Poseidon

Paestum

(See page 109)

FIG. 10—A Krater Vase, With Athena and Heracles

Louvre, Paris

(See page 220)

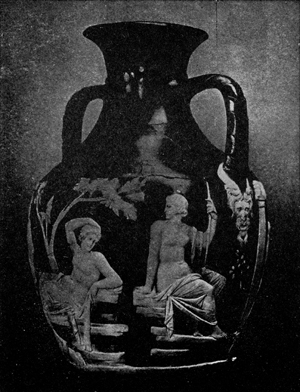

FIG. 11—The Portland Vase

British Museum

(See page 616)

FIG. 12—The François Vase

Archeological Museum, Florence

(See page 219)

FIG. 13—A Kore, or Maiden

Acropolis Museum, Athens

(See page 222)

FIG. 14—The “Choiseul-Gouffie?

Apollo”

Acropolis Museum, Athens

(See page 222)

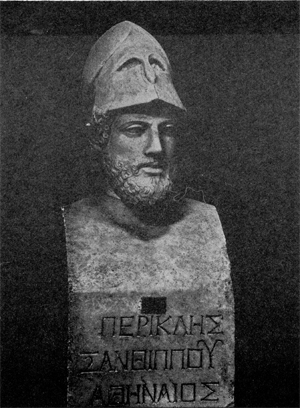

FIG. 15—Pericles

British Museum

(See page 248)

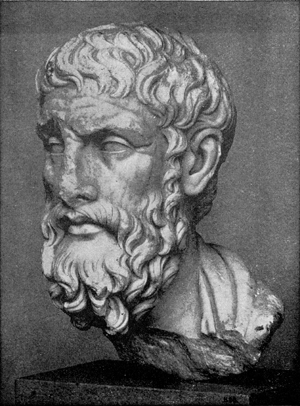

FIG. 16—Epicurus

Metropolitan Museum, New York

(See page 644)

FIG. 17—Orpheus, Eurydice, and Hermes

Naples Museum

(See page 319)

FIG. 18—“Birth of Aphrodite”

From the “Ludovisi Throne.” Museo delle Terme, Rome

(See page 319)

FIG. 19—“Ludovisi Throne,” Right Base

Museo delle Terme, Rome

(See page 319)

FIG. 20—“Ludovisi Thronem,” Left Base

Museo delle Terme, Rome

(See page 319)

FIG. 21—The Diadumenos.

Roman copy, after Polycleitus (?)

Athens Museum

(See page 322)

FIG. 22—Apollo Sauroctonos.

Roman copy, after Praxiteles (?)

Louvre, Paris

(See page 496)

FIG. 23—The Discus Thrower. Roman copy, after Myron (?)

Museo delle Terme, Rome

(See page 323)

FIG. 24—The “Dreaming Athena”

An anonymous relief, probably of the fifth century.

Acropolis Museum, Athens

(See page 319)

FIG. 25—The Rape of the Lapith Bride

From the west pediment of the temple of Zeus. Olympia Museum

(See page 328)

FIG. 26—Stela of Damasistrate

Athens Museum

(See page 318)

FIG. 27—Heracles and Atlas

Metope from the temple of Zeus. Olympia Museum

(See page 328)

FIG. 28—Nike Fixing Her Sandal

From the temple of Nike Apteros. Acropolis Museum, Athens

(See page 331)

FIG. 29—Propylaea and temple of Nike Apteros

(See page 331)

FIG. 30—The Charioteer of Delphi

Delphi Museum

(See page 221)

FIG. 31—A Caryatid from the Erechtheum

British Museum

(See page 332)

(See page 332)

FIG. 33—Goddesses and “Iris”

East pediment of the Parthenon. British Museum

(See page 333)

FIG. 34—“Cecrops and Daughter”

West pediment of the Parthenon. British Museum

(See page 334)

FIG. 35—Horsemen, from the West Frieze of the Parthenon

British Museum

(See page 334)

FIG. 36—Sophocles

Lateran Museum, Rome

(See page 391)

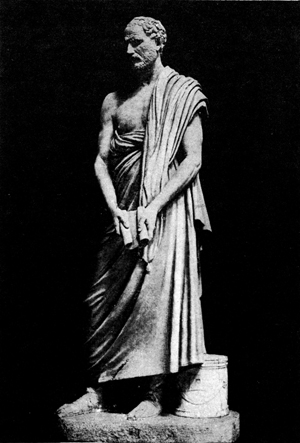

FIG. 37—Demosthenes

Vatican, Rome

(See page 478)

FIG. 38—A Tanagra Statuette

Metropolitan Museum, New York

(See page 492)

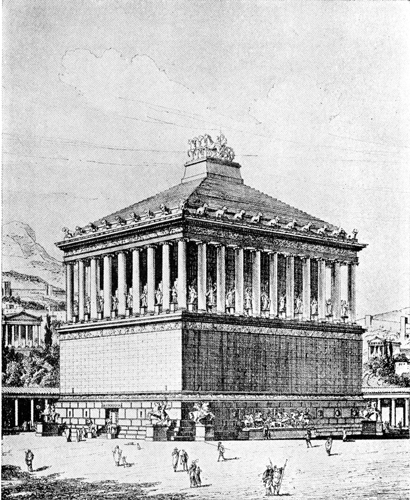

FIG. 39—The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus

A reconstruction. After Adler

(See page 494)

FIG. 40—Relief from the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus

British Museum

(See page 494)

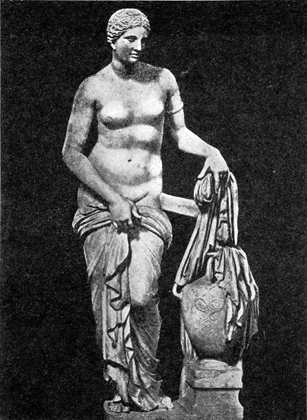

FIG. 41—The “Aphrodite of Cnidus”

Vatican, Rome

(See page 495)

FIG. 42—The Nike of Paeonius

Olympia Museum

(See page 324)

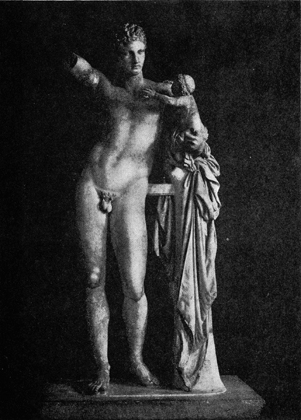

FIG. 43—The Hermes of Praxiteles

Olympia Museum

(See page 496)

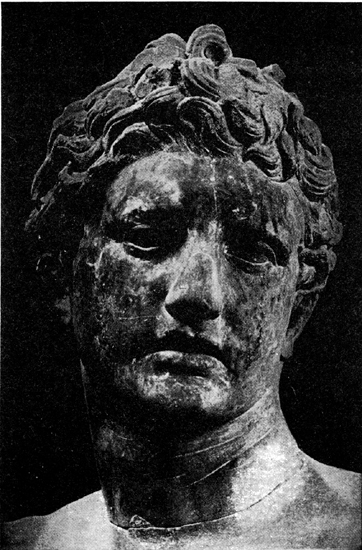

FIG. 44—Head of Praxiteles’ Hermes

Olympia Museum

(See page 496)

FIG. 45—The Doryphoros of Polycleitus.

As reproduced by Apollonius

Naples Museum

(See page 323)

FIG. 46—Head of Meleager.

Roman copy, after Scopas (?)

Villa Medici, Rome

(See page 497)

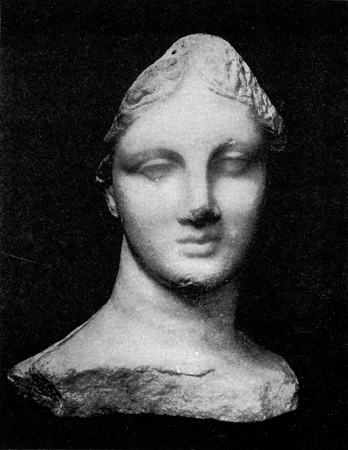

FIG. 47—Head of a Girl, from Chios

Boston Museum

(See page 499)

FIG. 48—The Apoxyomenos. A Roman copy, after Lysippus (?)

Vatican, Rome

(See page 498)

FIG. 49—The Raging (or Dancing) Maenad

Roman copy, after Scopas (?)

Dresden Albertinum

(See page 498)

FIG. 50—A Daughter of Niobe

Banca Comercial, Milan

FIG. 51—The Aphrodite of Cyrene

Museo delle Terme. Rome

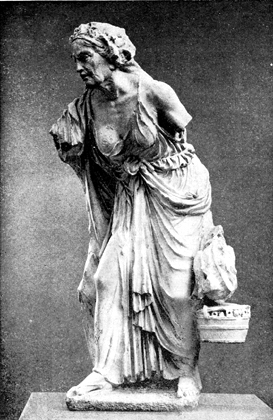

FIG. 52—The Demeter of Cnidus

British Museum

(See page 499)

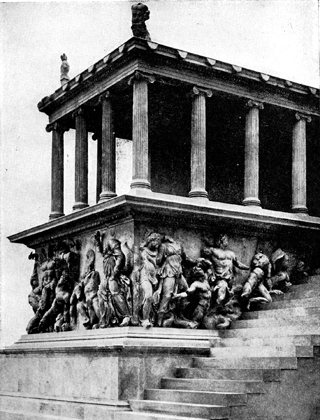

FIG. 53—Altar of Zeus at Pergamum

A reconstruction. State Museum, Berlin

(See page 618)

FIG. 54—Frieze from the Altar of Zeus at Pergamum

State Museum, Berlin

(See page 623)

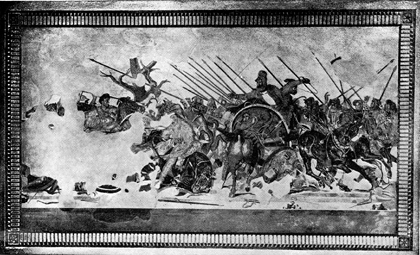

FIG. 55—The Battle of Issus. Mosaic found at Pompeii

Naples Museum

(See page 620)

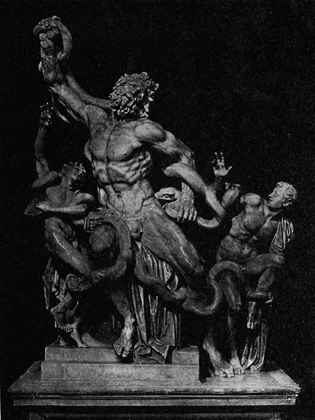

FIG. 56—The Laocoön

Vatican, Rome

(See page 622)

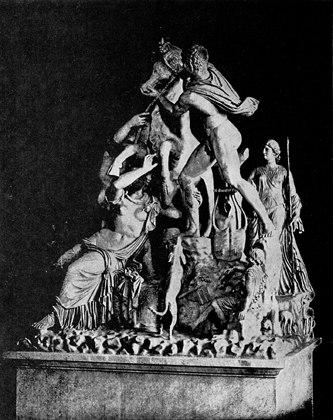

FIG. 57—The Farnese Bull

Naples Museum

(See page 623)

FIG. 58—The “Alexander” Sarcophagus

Constantinople Museum

(See page 623)

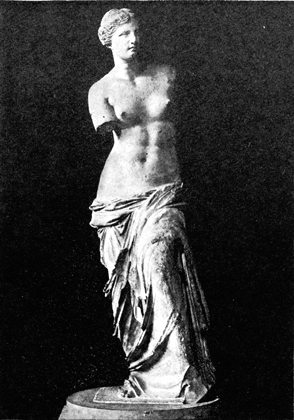

FIG. 59—The Aphrodite of Melos

Louvre, Paris

(See page 624)

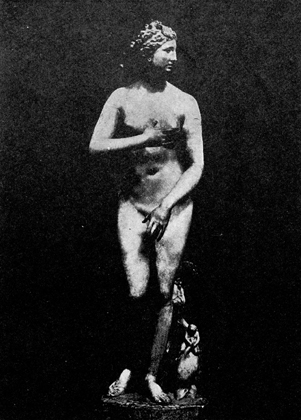

FIG. 60—The Venus de’ Medici

Uffizi Gallery, Florence

(See page 624)

FIG. 61—The “Victory of Samothrace”

Louvre, Paris

(See page 624)

FIG. 62—Hellenistic Portrait Head

Naples Museum

FIG. 63—The “Old Market Woman”

Metropolitan Museum, New York

(See page 626)

FIG. 64—The Prize Fighter

Museo delle Terme, Rome

Beneath the seated deities of the frieze was the entrance to the inner temple. The interior was relatively small; much of the space was taken up by two double-storied Doric colonnades that supported the roof, and divided the naos into a nave and two aisles; while in the western end Athene Parthenos blinded her worshipers with the gold of her raiment, or frightened them with her spear and shield and snakes. Behind her was the Room of the Virgins, adorned with four columns in the Ionic style. The marble tiles of the roof were sufficiently translucent to let some light into the nave, and yet opaque enough to keep out the heat; moreover, piety, like love, deprecates the sun. The cornices were decorated with careful detail, surmounted with terra-cotta acroteria, and armed with gargoyles to carry off the rain. Many parts of the temple were painted, not in subdued colors but in bright tints of yellow, blue, and red. The marble was washed with a stain of saffron and milk; the triglyphs and parts of the molding were blue; the frieze had a blue background, the metopes a red, and every figure in them was colored.52 A people accustomed to a Mediterranean sky can bear and relish brighter hues than those that suit the clouded atmosphere of northern Europe. Today, shorn of its colors, the Parthenon is most beautiful at night, when through every columned space come changing vistas of sky, or the ever worshipful moon, or the lights of the sleeping city mingling with the stars.*

Greek art was the greatest of Greek products; for though its masterpieces have yielded one by one to the voracity of time, their form and spirit still survive sufficiently to be a guide and stimulus to many arts, many generations, and many lands. There were faults here, as in all that men do. The sculpture was too physical, and rarely reached the soul; it moves us more often to admire its perfection than to feel its life. The architecture was narrowly limited in form and style, and clung across a thousand years to the simple rectangle of the Mycenaean megaron. It achieved almost nothing in secular fields; it attempted only the easier problems of construction, and avoided difficult tasks like the arch and the vault, which might have given it greater scope. It held up its roofs with the clumsy expedient of internal and superimposed colonnades. It crowded the interior of its temples with statues whose size was out of proportion to the edifice, and whose ornamentation lacked the simplicity and restraint that we expect of the classic style.*

But no faults can outweigh the fact that Greek art created the classic style. The essence of that style—if the theme of this chapter may be restated in closing—is order and form: moderation in design, expression, and decoration; proportion in the parts and unity in the whole; the supremacy of reason without the extinction of feeling; a quiet perfection that is content with simplicity, and a sublimity that owes nothing to size. No other style but the Gothic has had so much influence; indeed, Greek statuary is still the ideal, and until yesterday the Greek column dominated architecture to the discouragement of more congenial forms. It is good that we are freeing ourselves from the Greeks; even perfection becomes oppressive when it will not change. But long after our liberation is complete we shall find instruction and stimulus in that art which was the life of reason in form, and in that classic style which was the most characteristic gift of Greece to mankind.