US Global Power and Me

Throughout my long life in this country, America has always been at war. Short wars, long wars, world war, Cold War, secret war, surrogate war, war on drugs, war on terror, but always some sort of war. While these wars were usually fought in far-off countries or continents, sparing us the unimaginable terrors of bombing, shelling, and mass evacuation, their reality invariably lurked just beneath the surface of American life. For me, they were there in the heavy drinking and dark moods of my father and his friends, combat veterans of World War II; in the defense industries that employed him and most of the men I knew growing up; in the state surveillance that seemed to follow my family; in the bitter antiwar protests that divided the country during my college years; and in the endless war on terror that has stumbled ever onward since 2001.

I was born in 1945 at the start of an “American Century” of untrammeled global dominion. For nearly eighty years, the wars fought to defend and extend that vision of world power have shaped the American character—our politics, the priorities of our government, and the mentality of our people. If Americans aspired to govern the world like ancient Athenians, inspiring citizens and allies alike with lofty ideals, we acted more like Spartans, steeling our sons for war from childhood and relegating their suffering to oblivion as adults. Yet it was that Athenian aspiration to dominion that led this country into one war after another. It was that unbending ambition for a global Pax Americana that has allowed war to shape this country’s character.

At great personal cost for those who fought such wars, this country has won not only a kind of security but unprecedented power and prosperity. At the end of World War II, the United States, alone among the planet’s developed nations, had been spared its mass destruction. America emerged from history’s most destructive conflict as an economic powerhouse responsible for more than half the world’s industrial output, consuming much of its raw materials, possessing its strongest currency, and girding the globe with its armed forces and their garrisons. The Soviet Union’s implosion at the close of the Cold War in 1991 again left America the richest, most powerful, most productive nation on the planet.

Though we would live our lives in the shadow of war and empire, my postwar “baby boom” generation was also privileged to grow up in a relatively safe society with a superior education system, excellent health care, affordable food, and opportunities once available only to aristocrats. None of this happened by accident. Every advantage came with a price paid at home and abroad by Americans and many others. Our country’s global power was first won in a world war that left fifty million dead. It was maintained throughout the Cold War by covert interventions to control foreign societies, a global military presence manifest in hundreds of overseas bases, and the rigorous suppression of domestic dissent. In the quarter century since the Cold War’s end, however, America’s social contract has frayed. The old bargain, shared sacrifice for shared prosperity, has given way, through Washington’s aggressive promotion of a global economy, to a rising disparity of incomes that has eroded the quality of middle-class life.

As an aspiring historian since seventh grade, I have remained more observer than actor, trying to make sense of the changing relationship between America and the world, attempting to understand our complex form of state power and our distinctive way of governing the globe. I consider myself fortunate to have grown up among middle-class families that served this state as soldiers, engineers, and later, on occasion, senior officials.

I was also privileged to attend schools that trained our future leaders, allowing me to observe firsthand the ethos that shaped those at the apex of American power, their character and worldview. For five years in the 1960s, I went to a small boarding school in Kent, Connecticut, that steeled its boys through relentless hazing and rigorous training for service to the state. Admiral Draper Kauffman (class of ’29), founder of the navy’s underwater demolition teams (forerunner of the SEALs), was the father of a classmate. Cyrus Vance (class of ’35), the future secretary of state, was a commencement speaker. Sir Richard Dearlove (class of ’63), later head of Britain’s MI-6, was a year ahead of me. Countless alumni were known to be in the CIA. Through its defining rituals, this small school tried to socialize us into a grand imperial design of the kind once espoused by East Coast elites back when America was first emerging as a world power. On Sundays after mass celebrated with Anglican high-church liturgy, the cascading sounds of English change ringing pealed for hours from the chapel bell tower. Every class had one or two British exchange students provided by the English-Speaking Union. Our curriculum followed the classical form of English boarding schools, with Latin or Greek required subjects. The school crew made periodic trips to the Henley Royal Regatta. All this was aimed at instilling a cultural affinity between American and British elites for shared global dominion.

Both family and school taught me that criticism was not only a right but a responsibility of citizenship. So it has been my role to observe, analyze, and, when I have something worth sharing, to write and sometimes to criticize. This is a complex society, elusive in its exercise of world power. It has taken many years of education and much of my life experience to gain some insight into the geopolitical dynamics that propelled the United States to global hegemony and are undoubtedly condemning it to decline.

Only days after my father’s graduation from the US Military Academy at West Point in June 1944, my parents married. That December, when he shipped out with the Eighty-Ninth Division for the war in Europe, my mother was pregnant with me. As an artillery forward observer, he was on the front lines in the Moselle, the Rhineland crossing, and onward through central Germany where his unit was the first to liberate a Nazi death camp. Typical of the veterans of that conflict, he only mentioned the war once, telling me in an offhand way when I was old enough to understand that the infantry company he fought with crossing the Rhine lost most of its two hundred men that day.

My birth coincided with the last months of World War II, just as the United States was ascending to unprecedented world power. As I grew up and we moved from one quiet street to another across America, war was always with us, just beneath the surface of family life. When my father wasn’t away at war in Europe or Korea, we lived mainly at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, home of the US Field Artillery. There his promotions finally got us out of squalid army housing and into pleasant quarters on a tree-lined street opposite the parade ground. I can still remember visiting the grave of Geronimo, the Apache chief whose capture in the 1880s and life sentence at Fort Sill ended the “Indian wars” in the Southwest. Climbing the stone marker above his grave at age five was my introduction to the past and its occupants as I touched those stones wondering about the great chief who lay below.

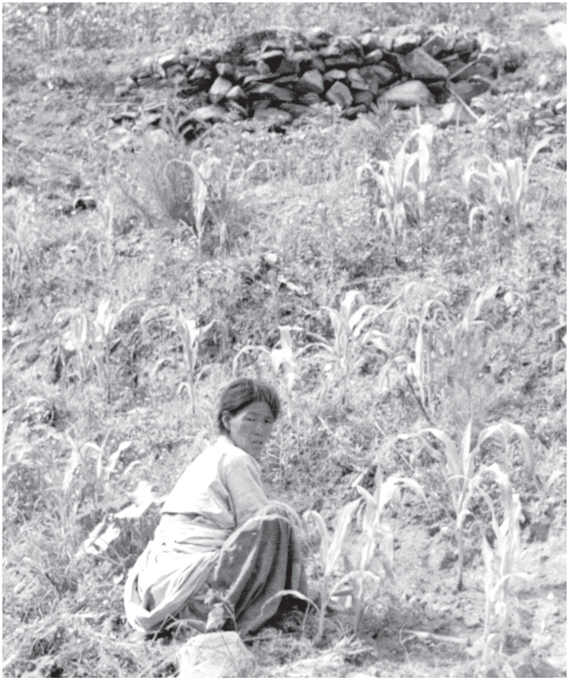

A few months after the Korean War started in June 1950, my father shipped out again with the field artillery for a yearlong combat tour, and we moved to Florida to be with my mother’s parents. In first grade, I had a map of Korea posted on my bedroom wall. Silver stars glued on it showed the position of my father’s unit as it moved around the peninsula. For the first time, I learned that the world actually had other countries. One memorable morning, I woke to find my father magically home from war. Allowed to skip school for the first and only time in my life, I sat with him in the breezeway that warm Florida morning as he showed me photos he had taken with his new Japanese camera of far-off battlefields—howitzer batteries firing, tents in the snow, and, most memorably, a disheveled Korean woman squatting in a field before a pile of rubble and staring directly into the lens. “Her house,” was my father’s only comment. It would remain an indelible image of war for the rest of my life.

After that combat tour, we returned to Fort Sill where, among other duties, my father was range officer for artillery training. Once during a night-firing exercise, he took me along, though I was only seven. I watched beneath the eerie white light of falling flares as his words into a phone unleashed barrages that exploded tanks and trucks on faraway hills—a memorable lesson in the power of America’s military arsenal.

After my father resigned his commission to become an electronics engineer, we followed him from one defense contract to another. Sperry Gyroscope on Long Island near New York City, Raytheon near Boston, and Aerospace Corporation in Los Angeles. Wherever we went, our neighbors were more or less like us—dad, the war veteran, mom, the suburban housewife, two or three kids, a dog, a small house, a mortgage, a car, a local church, crowded schools, and, of course, scouts. When I was in elementary school, it all felt pretty nice. Nobody had much money, but everyone seemed happy. The dads had good jobs. When you got sick, a doctor came to the house. The cafeteria food at school was fine. I got new bikes on my seventh and eleventh birthdays. There were always kids on the street to play with. Safety wasn’t even a concept, just a given. Looking back, it seemed as if America had won more than a war.

Not long after we bought a house in Sudbury, a Boston suburb, in the mid-1950s, the Katzenbachs moved in next door. Their son Larry was a year older and already in high school, but he soon became my best friend (for life, as it turned out). Their daughter Matilda was my younger sister’s playmate. Maude Katzenbach became my mother’s confidante and close friend. Even after both families moved away, they carried on a correspondence that continued for nearly fifty years about children, divorces, careers, retirement—and, let’s face it—the suffering they shared as wives of those warrior males.

Woman with remains of house, South Korea, 1951. (Photo by Alfred M. McCoy, Jr.)

Like my father, Ed Katzenbach was a combat veteran of World War II. As a marine officer, he had fought for four years through nineteen blood-soaked landings on Japanese-occupied islands across the Pacific.1 Every day, my dad drove to the Raytheon Laboratory in a nearby suburb to design radar for the country’s missile defense system. And every morning, Larry’s dad took the train into Boston where he was director of defense studies at Harvard University, planning strategy for the nation’s military.

Though they lived next door and looked like us, the Katzenbachs were different. They had an aura of American aristocracy about them. Ed went to Princeton; his father had been New Jersey’s attorney general; his uncle was a justice on that state’s supreme court.2 They had some money, not much, but enough to do things we couldn’t afford, like lease a fishing cabin in Maine. One memorable spring when I was thirteen, the Katzenbachs took me along for ice-out fishing—hikes through the melting snow, splitting wood for the stove, and endlessly trolling the lake, which had water so clear that you could actually see the trout swim right up to examine the lure and then never quite bite.

Beneath his faint smile, Ed Katzenbach was troubled, fighting serious depression and an ambitious colleague named Henry Kissinger who was maneuvering for his job. Sometimes, after a night of drinking and arguing with his wife, he would retreat to the basement and fire his service pistol into the wall. When John F. Kennedy was elected president, the family moved to Washington and he became deputy assistant secretary of defense for education. His brother Nicholas would serve in Robert Kennedy’s Justice Department, becoming famous in June 1963 for confronting Governor George Wallace on the steps of the University of Alabama in the struggle over integration. Visiting Larry in Washington during high school holidays left me with memories of dinner table stories about the Katzenbach brothers working alongside the Kennedy brothers. Larry’s cousins went to parties at the White House. His classmates at the elite Sidwell Friends School were the children of ambassadors and cabinet officials.

Two years after the Katzenbachs went to Washington, our family moved to Los Angeles. Though just a few years out of the army, my father, with an IQ of 195 and an advanced engineering degree from the Illinois Institute of Technology, was climbing fast in the world of the military-industrial complex. He had become chief systems engineer for Aerospace Corporation’s Defense Communications Satellite System, a half-billion-dollar effort to launch the world’s first global satellite network. In contrast to the dirt floors or repurposed barracks of our old army housing, we now lived on a street of movie-star mansions in Pacific Palisades, right around the corner from Ronald Reagan. When a Titan III-C rocket blasted off from Cape Canaveral in 1966 carrying a payload of eight satellites, engineers from Aerospace Corporation crowded our living room awaiting news. After one of them stood up to read the telegram from Cape Canaveral confirming the system was live, the room rang with martini-soaked cheers.3

Many years later when I would start writing about the architecture of US global power, turning to the recondite aerospace technology for drones, satellites, and space warfare would seem intuitive. This family background would lead me to recognize, unlike many scholars, that a satellite system was a central pillar in that architecture.

Prosperity’s glow turned out to have a darker side. My father had suffered more in two wars than we knew. During our first years in Los Angeles, he drank, gambled, caroused, and racked up debts that nearly bankrupted us. Little more than a year after asking my mother for a divorce and walking out, he died in an alcohol-fueled accident at the age of forty-five. Meanwhile, Nicholas Katzenbach became attorney general under President Lyndon Johnson and went on to top jobs at IBM. But Ed himself struggled with depression, divorce, and thoughts of death, compounded by “an inconsolable heartbreak” over the sacrifice of so many soldiers’ lives in the moral and strategic quagmire of the war in Vietnam. At the age of fifty-five, he pointed that service pistol at himself instead of the wall.4 Larry, deeply scarred, grieved with a sonnet in the New York Times.5

It’s March. Outside, the snow tries yet once more

To wrap the melting wounds of spring—the ruts,

The footprints sunk in soggy ground. I pour

Some tea to soothe a memory that cuts.

Two years ago, in March, I phoned. We spoke.

I knew his thoughts, but talked of hopes, of books,

Of ice-out trout in Maine. I told a joke.

“Let’s fish,” I said. “I’ll bet they’ll go for hooks.” …

His life was always fish who’d never bite.

A suicide that spring, he said. “We’ll see.

Bye. Thanks.” I wish this snow could bandage me.

Ed Katzenbach and my father were not exceptional. Every family I knew well enough to know what was going on behind the façade wives maintained in those days had similar problems. Most dads drank hard. At my parents’ parties back in the 1950s, those veterans would down four or five drinks—not beer and wine but bourbon and vodka. Their wives pretended that an entire generation of veterans being on liquid therapy was perfectly normal. Those men, in turn, inflicted the war’s trauma on their families. A study published right after World War II by two army doctors reported that sixty days of continuous combat turned 98 percent of soldiers into psychiatric casualties, vulnerable to what would later be called post-traumatic stress disorder.6

Watching the invisible wounds of war slowly destroy Ed Katzenbach and my father, who were as smart and strong as any men could be, taught me that Washington’s bid for world power carried heavy costs. Years later when the fighting started in South Vietnam, I was not surprised that many in my generation did not seem eager to repeat their fathers’ experience.

With the war in Vietnam escalating relentlessly, I joined the protesters who occupied campus buildings during my senior year at Columbia University in 1968. Beaten by the riot police, I spent a memorable night in a crowded cell at the Tombs, Manhattan’s infamous municipal jail.

The next year, at Berkeley for a master’s degree in Asian Studies, I experienced the People’s Park demonstrations that brought tear gas, riot police, and the National Guard to campus. As I stepped out of a medieval Japanese literature class, a San Francisco motorcycle cop in full black leathers dropped to one knee, raised his shotgun, and pumped a few rounds of birdshot into my legs. Others, not so lucky, were hit by bigger, lethal buckshot, blinding one, killing another.

The next fall, I moved on to Yale for my doctorate, but the Ivy League in those days was no ivory tower. The Justice Department had indicted Black Panther leader Bobby Seale for a local murder, and the May Day protests that filled the New Haven green also shut down the campus for a week. Almost simultaneously, President Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia, and student protests closed hundreds of campuses across America for the rest of the semester.

Not surprisingly perhaps, in all this tumult the focus of my studies shifted from Japan to Southeast Asia, and from the past to the present war in Vietnam. Yes, that war. So what did I do about the draft? During my first semester at Yale, on December 1, 1969, to be precise, the Selective Service cut up the calendar for a lottery. The first one hundred birthdays picked were certain to be drafted and any dates above two hundred likely exempt. My birthday, June 8, was the very last date drawn, not number 365 but 366 (don’t forget leap year)—the only lottery I have ever won, except for a Sunbeam electric frying pan in a high school raffle (still have it; it still works). Through a complex moral calculus typical of the 1960s, I decided that my draft exemption, although acquired by sheer luck, required that I devote myself, above all else, to thinking about, writing about, and working to end the war in Vietnam.

During those campus protests over Cambodia in the spring of 1970, our small group of graduate students in Southeast Asian history at Yale realized that the US strategic predicament in Indochina would soon require an invasion of Laos in an attempt to cut the flow of enemy supplies into South Vietnam. So, while protests over Cambodia swept campuses nationwide, we were huddled inside the library, preparing for the next invasion by editing a book of essays on Laos for the publisher Harper & Row.7 A few months after that book appeared, one of the company’s junior editors, Elizabeth Jakab, intrigued by an account we had included about that country’s opium crop, telephoned from New York to ask if I could research and write a “quickie” paperback about the history behind the heroin epidemic then infecting the US Army in Vietnam.

I promptly started the research at my student carrel in the Gothic tower that is Yale’s Sterling Library, tracking colonial reports about the Southeast Asian opium trade that ended suddenly in the 1950s, just when the story got interesting. So, quite tentatively at first, I stepped outside the library to do a few interviews and soon found myself following an investigative trail that circled the globe. First, I traveled across America for meetings with retired CIA operatives. Then, across the Pacific to Hong Kong to study drug syndicates. Next, I went south to Saigon, then the capital of South Vietnam, to investigate the heroin traffic that was targeting the GIs, and on into the hills of Laos to observe CIA alliances with opium warlords and the hill tribe guerrillas who grew the opium poppy. Finally, I flew from Singapore to Paris for interviews with retired French intelligence officers about their opium trafficking during the first Indochina War.

The drug traffic that supplied heroin for the US troops fighting in South Vietnam was not, I discovered, exclusively the work of criminals. Once the opium left tribal poppy fields in Laos, the traffic required official complicity at every level. The helicopters of Air America, the airline the CIA ran, carried raw opium out of the villages of its hill tribe allies. The commander of the Royal Lao Army, a close American collaborator, operated the world’s largest heroin lab and was so oblivious to the implications of the traffic that he opened his opium ledgers for my inspection. Several of Saigon’s top generals were complicit in the drug’s distribution to US soldiers. By 1971, this web of collusion, according to a White House survey of a thousand veterans, ensured that heroin would be “commonly used” by 34 percent of American troops in South Vietnam.8

None of this had been covered in my college history seminars. I had no models for researching an uncharted netherworld of crime and covert operations. After stepping off the plane in Saigon, body slammed by the tropical heat, I found myself in a sprawling foreign city of four million, lost in a swarm of snarling motorcycles and a maze of nameless streets, without contacts or a clue about how to probe these secrets. Every day on the heroin trail confronted me with new challenges—where to look, what to look for, and, above all, how to ask hard questions.

Reading all that history had, however, taught me something I didn’t know I knew. Instead of confronting my sources with questions about sensitive current events, I started with the French colonial past when the opium trade was still legal, gradually uncovering the underlying, unchanging logistics of drug production. As I followed this historical trail into the present, when the traffic became illegal and dangerously controversial, I began to use pieces from this past to assemble the present puzzle, until the names of contemporary dealers fell into place. In short, I had crafted a historical method that would prove, over the next forty years of my career, surprisingly useful in analyzing a diverse array of foreign policy controversies—CIA alliances with drug lords, the agency’s propagation of psychological torture, and our spreading state surveillance.

Those months on the road, meeting gangsters and warlords in isolated places, offered only one bit of real danger. While hiking in the mountains of Laos, interviewing Hmong farmers about their opium shipments on CIA helicopters, I was descending a steep slope when a burst of bullets ripped the ground at my feet. I had walked into an ambush by agency mercenaries. While the five Hmong militia escorts whom the local village headman had prudently provided laid down a covering fire, my photographer John Everingham and I flattened ourselves in the elephant grass and crawled through the mud to safety. Without those armed escorts, my research would have been at an end and so would I.

Six months and 30,000 miles later, I returned to New Haven. My investigation of CIA alliances with drug lords had taught me more than I could have imagined about the covert aspects of US global power. Settling into my attic apartment for an academic year of writing, I was confident that I knew more than enough for a book on this unconventional topic. But my education, it turned out, was just beginning.

Within weeks, my scholarly isolation was interrupted by a massive, middle-aged guy in a suit who appeared at my front door and identified himself as Tom Tripodi, senior agent for the Bureau of Narcotics, which later became the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). His agency, he confessed during a second visit, was worried about my writing and he had been sent to investigate. He needed something to tell his superiors. Tom was a guy you could trust. So I showed him a few draft pages of my book. He disappeared into the living room for a while and came back saying, “Pretty good stuff. You got your ducks in a row.” But there were some things, he added, that weren’t quite right, some things he could help me fix.

Tom was my first reader. Later, I would hand him whole chapters and he would sit in a rocking chair, shirt sleeves rolled up, revolver in his shoulder holster, sipping coffee, scribbling corrections in the margins, and telling fabulous stories—like the time Jersey Mafia boss “Bayonne Joe” Zicarelli tried to buy a thousand rifles from a local gun store to overthrow Fidel Castro. Or when some CIA covert warrior came home for a vacation and had to be escorted everywhere so he didn’t kill somebody in a supermarket aisle. Best of all, there was the one about how the Bureau of Narcotics caught French intelligence protecting the Corsican syndicates smuggling heroin into New York City. Some of his stories, usually unacknowledged, would appear in my book, The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. These conversations with an undercover operative, who had trained Cuban exiles for the CIA in Florida and later investigated Mafia heroin syndicates for the DEA in Sicily, were akin to an advanced seminar, a master class in covert operations.9

In the summer of 1972, with the book at press, I went to Washington to testify before Congress. As I was making the rounds of congressional offices on Capitol Hill, my editor rang unexpectedly and summoned me to New York for a meeting with the president and vice president of Harper & Row, my book’s publisher. Ushered into an executive suite overlooking the spires of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, I listened to them tell me that Cord Meyer Jr., the CIA’s assistant deputy director for plans (actually, covert operations), had called on their company’s president emeritus, Cass Canfield, Sr. The visit was no accident, for Canfield, according to an authoritative history, “enjoyed prolific links to the world of intelligence, both as a former psychological warfare officer and as a close personal friend of Allen Dulles,” the ex-head of the CIA. Meyer denounced my book as a threat to national security. He asked Canfield, also an old friend, to quietly suppress it.10

I was in serious trouble. Not only was Meyer a senior CIA official but he also had impeccable social connections and covert assets in every corner of American intellectual life. After graduating from Yale in 1942, he served with the marines in the Pacific, writing eloquent war dispatches published in Atlantic Monthly. He later worked with the US delegation drafting the UN charter. Personally recruited by spymaster Allen Dulles, Meyer joined the CIA in 1951 and was soon running its International Organizations Division, which “constituted the greatest single concentration of covert political and propaganda activities of the by now octopus-like CIA,” including Operation Mockingbird that planted disinformation in major US newspapers meant to aid agency operations.11 Informed sources told me that the CIA still had assets inside every major New York publisher and it already had every page of my manuscript.

As the child of a wealthy New York family, Meyer moved in elite social circles, meeting and marrying Mary Pinchot, the niece of Gifford Pinchot, founder of the US Forestry Service and a former governor of Pennsylvania. Pinchot was a breathtaking beauty who later became President Kennedy’s mistress, making dozens of secret visits to the White House. When she was found shot dead along the banks of a canal in Washington in 1964, the head of CIA counterintelligence, James Jesus Angleton, another Yale alumnus, broke into her home in an unsuccessful attempt to secure her diary. Mary’s sister Toni and her husband, Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, later found the diary and gave it to Angleton for destruction by the agency.12

Cord was in New York’s Social Register of fine families along with my publisher, Mr. Canfield, which added a dash of social cachet to the pressure to suppress my book. By the time he walked into Harper & Row’s office in the summer of 1972, two decades of CIA service had changed Meyer from a liberal idealist into “a relentless, implacable advocate for his own ideas,” driven by “a paranoiac distrust of everyone who didn’t agree with him” and a manner that was “histrionic and even bellicose.”13 An unpublished twenty-six-year-old graduate student versus the master of CIA media manipulation. It was hardly a fair fight. I began to fear my book would never appear.

To his credit, Mr. Canfield refused Meyer’s request to suppress the book but did allow the agency a chance to review the manuscript prior to publication. Instead of waiting quietly for the CIA’s critique, I contacted Seymour Hersh, then an investigative reporter for the New York Times. The same day the CIA courier arrived from Langley to collect my manuscript, Hersh swept through Harper & Row’s offices like a tropical storm and his exposé of the CIA’s attempt at censorship soon appeared on the paper’s front page.14 Other national media organizations followed his lead. Faced with a barrage of negative coverage, the CIA gave Harper & Row a critique full of unconvincing denials. The book was published unaltered.

I had learned another important lesson: the Constitution’s protection of press freedom could check even the world’s most powerful espionage agency. Meyer reportedly learned the same lesson. According to his obituary in the Washington Post, “It was assumed that Mr. Meyer would eventually advance” to head CIA covert operations, “but the public disclosure about the book deal … apparently dampened his prospects.” He was instead exiled to London and eased into early retirement.15

Meyer and his colleagues were not, however, used to losing. Defeated in the public arena, the CIA retreated to the shadows and retaliated by tugging at every thread in the threadbare life of a graduate student. Over the next few months, federal officials from HEW (Health, Education, and Welfare) turned up at Yale to investigate my graduate fellowship. The IRS audited my poverty-level income. The FBI tapped my New Haven telephone, something I learned years later from a class-action lawsuit. At the height of this controversy in August 1972, FBI agents told the bureau’s director they had “conducted [an] investigation concerning McCoy,” searching the files compiled on me for the past two years and interviewing numerous “sources whose identities are concealed [who] have furnished reliable information in the past”—thereby producing an eleven-page report detailing my birth, education, and campus antiwar activities.16 A college classmate I hadn’t seen in four years, and who served in military intelligence, magically appeared at my side in the book section of the Yale Co-op, seemingly eager to resume our relationship. The same week a laudatory review of my book appeared on the front page of the New York Times Book Review, an extraordinary achievement for any historian, Yale’s History Department placed me on academic probation. Unless I could somehow do a year’s overdue work in a single semester, I faced dismissal.17

In those days, the ties between the CIA and Yale were wide and deep. The campus residential colleges screened students, including future CIA director Porter Goss, for possible careers in espionage. Alumni like Cord Meyer and James Angleton held senior slots at the agency. Had I not had a faculty adviser visiting from Germany, a stranger to this covert nexus, that probation would likely have become expulsion, ending my academic career and destroying my credibility. At a personal level, I was discovering just how deep the country’s intelligence agencies could reach, even in a democracy, leaving no part of my life untouched—my publisher, my university, my taxes, my phone, and even my friends.

During these difficult days, New York representative Ogden Reid, a ranking member of the House Foreign Relations Committee, telephoned to say that he was sending staff investigators to Laos to look into the opium situation. Amid all this controversy, a CIA helicopter landed near the village where I had escaped that ambush and flew the Hmong headman who had helped my research to an agency airstrip where a CIA interrogator made it clear that he had better deny what he had said to me about the opium. Fearing “they will send a helicopter to arrest me, or … soldiers to shoot me,” the Hmong headman did just that.18

Although I had won the first battle with a media blitz, the CIA was winning the longer bureaucratic war. By silencing my sources and denying any culpability, its officials convinced Congress that it was innocent of any direct complicity in the Indochina drug trade. During Senate hearings into CIA assassinations by the famed Church Committee three years later, Congress accepted the agency’s assurance that none of its operatives had been directly involved in heroin trafficking (an allegation I had never made). The committee’s report did confirm the core of my critique, finding that “the CIA is particularly vulnerable to criticism” over indigenous assets in Laos “of considerable importance to the Agency,” including “people who either were known to be, or were suspected of being, involved in narcotics trafficking.” But the senators did not press the CIA for any resolution or reform of what its own inspector general had called the “particular dilemma” posed by those alliances with drug lords—the key aspect, in my view, of its complicity in the traffic.19 During the mid-1970s, as the flow of drugs into the United States slowed and the number of addicts declined, the heroin problem receded into the inner cities, and the media moved on to new sensations. The issue would largely be forgotten for a decade until the crack-cocaine epidemic swept America’s cities

in the late 1980s.

Almost by accident, I had launched my academic career by doing something a bit different. Back in the 1970s, most specialists in international studies went overseas for “fieldwork” focused on aspects of indigenous societies untouched by foreign influence, as if the globalization of the past two centuries had never happened. Instead, I had focused on interactions between American officials and their foreign allies—the lynchpin, in my view, of any empire. In one of life’s small ironies, I would have to leave America to better understand the sources of American power.

Embedded within that study of drug trafficking was an analytical approach that would take me, almost unwittingly, on a lifelong exploration of US global hegemony in its many manifestations, including diplomatic alliances, CIA intervention, military technology, trade, torture, and global surveillance. Step-by-step, topic-by-topic, decade-after-decade, I would slowly accumulate sufficient understanding of the parts to try to assemble the whole—the overall character of US global power and the forces that would contribute to its perpetuation or decline. By studying how each of these current attributes was shaped by the actual exercise of this power overseas and over time, I slowly came to see a striking continuity and coherence in Washington’s century-long rise to global dominion. Its reliance on surveillance, for example, first appeared in the colonial Philippines around 1900; CIA covert intervention and torture techniques emerged at the start of the Cold War in the 1950s; and much of its futuristic robotic aerospace technology had its first trial in the war in Vietnam of the 1960s.

The Cold War made this scholarly work difficult. For decades, its ideological constraints would bar most academics from even naming the topic that needed the most study. Once the Cold War ended in 1991, I could finally admit to myself that I had been researching the rise of the United States as history’s most powerful “empire.” Not only was this imperium the first to cover the entire globe, but it was also the only one in two centuries largely exempt from serious scholarly study. Since the Soviet bloc used the Marxist-inflected term “imperialist” to denigrate the United States, this country’s diplomatic historians, operating in a Cold War mode, subscribed to the idea of “American exceptionalism.” The United States might be a “world leader” or even a “great power,” but never an empire. Our enemy, the Soviet Union, was the one with an empire.

Within the Cold War’s not-so-subtle pressures for affirmation of American foreign policy, critical voices, even within the academy, were few. The handful of Marxist historians still teaching often reduced the study of empires—the most complex and multifaceted of all political organizations—to a narrow, rather dull analysis of their economic causation. By contrast, a small group of historians affiliated with the so-called Wisconsin school, led by the historian William Appleman Williams, developed a more nuanced critique of US diplomatic history. Like many graduate students during the 1960s, I immersed myself in his landmark text, The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, scribbling notes in the margins of a well-worn paperback that I still have on my bookshelf. But I could not see a way to apply his approach to my own study of Asia, a field whose leading academics were still scarred by Cold War accusations of subversion.

As a graduate student in history during the 1970s, I thus found myself caught in a political conundrum that precluded even naming my subject, much less theorizing about it. Yet Yale’s graduate school, through its close ties to English universities where imperial history still thrived, offered a back door into this otherwise closed realm of inquiry. In my first year at Yale, I took a seminar on “comparative imperialism” from Oxford historian David Fieldhouse, later considered the world’s “leading imperial economic historian,” and another on British imperial diplomacy in East Asia with Ian Nish from the London School of Economics.20

Both were erudite, engaging men, but Fieldhouse made the concept of empire come alive for me with personal anecdotes, like one about a temperamental relative who sprayed ink from his pen across an overbearing supervisor’s white shirt and wound up a lowly colonial official in West Africa. Yet at a conference of graduate students hosted by the antiwar group Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars, I recoiled from a proposed commitment to “anti-imperialism,” even though I was then the organization’s national coordinator. In the context of the Cold War, the very name of my field had become an unpalatable political epithet.

With the last US combat troops home from Vietnam and the war winding down, I needed to get my academic career back on track. So, having worked double-time to finish those overdue Yale degree requirements, I moved to the Philippines in the fall of 1973 for dissertation fieldwork. During the next three years in the central Philippines, I learned a local language and immersed myself in the country’s social history. As it happened, the Philippines was the only place on the planet where almost a half century of US colonial rule made the study of the American empire a serious, non-polemical exercise.

Looking back, it was a lucky choice. Over the next forty years, Filipinos would prove excellent teachers when it came to their country’s long, complex relationship with America. Often they cast aside my ill-informed questions and taught me about facets of power I didn’t even know I needed to know.

My doctoral dissertation focused on what seemed like a purely academic topic: the impact of World War II on the Philippine response to US colonial rule. Yet only a few months after I started my work, President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law and launched what became fourteen years of military dictatorship. To justify his ever-tightening grip on power, he insisted that his heroism as an anti-Japanese guerrilla had steeled him to lead the nation through troubled times. He would redouble these claims a decade later during his reelection campaign against Corazon Aquino. As that contest heated up in late 1985, I happened to be in Washington on sabbatical from an Australian university for further research to turn my dissertation on World War II into a book. There, in the National Archives, I tracked down some long forgotten US Army files that revealed just how fraudulent Marcos’s tales of wartime heroism really were. Those revelations made it onto the front pages of the New York Times and the Philippine Daily Inquirer just two weeks before that historic election.21

Then, after a million Filipinos assembled on the streets of Manila to force Marcos into exile, I found myself back in the Philippines as a consultant for an HBO television miniseries on that event, and soon discovered that this mass uprising had, in fact, been sparked by an abortive military coup, influenced in part by the CIA’s invisible hand.

It was a remarkable story, revealing to me another dimension of the covert power of the United States. Just weeks after Marcos won reelection through massive fraud in February 1986, his defense minister and a group of dissident colonels met in secret to set the date for a military coup. Only a few days later, two of these colonels received an urgent call from a US military attaché, Major Victor Raphael—a friend of the rebel officers and, they believed, the resident agent of the Defense Intelligence Agency. According to the colonels, Raphael had a message “from the highest level of the U.S. government,” telling them, first, that it “will not recognize nor look kindly on any unconstitutional move. Two, in case you have to make moves along the line of enlightened self-defense, the U.S. will understand it.” So, the rebel colonels persisted in their plans, interpreting his message simply as the Americans “betting on all the horses.” Indeed, just before their projected coup, the chief of the CIA’s Manila station, Norbert Garrett, warned Marcos’s security officer, General Fabian Ver, to strengthen the presidential palace’s defenses against a possible coup. Within hours, the palace guard went on full alert. The colonels’ coup plot was blown, but the way was opened for that mass uprising labeled “people power.”22

Listening to the colonels’ tale of US double-dealing, I was impressed by the way the CIA had calibrated its every move to minimize the violence and maximize American influence, whatever the outcome. I had also gained firsthand a sense of how the agency controlled US surrogates in those Cold War years through covert operations, thereby maintaining Washington’s dominion over half the globe.

As for Major Raphael, after I published his name in the Manila press, he was soon sent home amid accusations that he was now supporting rebel officers conspiring to overthrow the new democratic government. Twenty years later in 2006, I sat opposite Victor Raphael, then a senior analyst for the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, during a daylong briefing for the outgoing US ambassador to Manila. With protocol dictating best behavior on both sides of the table, neither of us acknowledged our shared past.

But there was also something a bit unsettling about those Filipino colonels who had been so open to being interviewed by me. The international press had lionized them as heroes in the overthrow of a brutal dictator. Maybe it was the tank of pet piranhas outside one colonel’s office, or another’s obsessive repetition of the word blood, but something about them sent me off on a yearlong search for their service records. What I found was that most of them had not served as line or staff officers. Most had worked in internal security, interrogating and, I discovered, torturing suspected anti-Marcos dissidents, thanks in part to some rather sophisticated US torture training.

While they launched another half-dozen coups over the next decade, I tracked down their victims and learned something of the transactional nature of the torture relationship: the victims suffered devastating psychological damage, but their interrogators, in almost equal measure, were empowered, their egos inflated beyond all imagining by their years breaking priests and professors for Marcos. Having shed their roles as uniformed servants of the state, they would, like latter-day Nietzchean supermen, now be its master.

These findings won an attentive audience in the Philippines. In America, however, the Cold War and its controversies about torture were over, limiting the audience for the book-length study I published in 1999.23 Further research uncovered striking similarities between Philippine torture techniques and those used in Latin America, indicating the CIA had been training allied agencies in those skills worldwide. But my paper reporting these findings aroused little interest a year later at an international human rights conference in Capetown, where activists from Asia, Africa, and Latin America were focused on bringing their own perpetrators to justice. I must admit, though, that I was relieved to set the study of that sordid subject aside and move on to other topics.

In April 2004, however, CBS broadcast those disturbing photos of US soldiers abusing Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib prison, forcing me to resume this troubling work. Looking at the now-infamous photo of a hooded Iraqi prisoner standing on a box, electrical wires hanging from his arms, I could see quite clearly the basic tenets of the CIA’s psychological torture doctrine of the Cold War era: the hood was for sensory deprivation and the arms were outstretched to cause self-inflicted pain. Just a few days later, I wrote in the Boston Globe: “The photos from Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison are snapshots not of simple brutality or a breakdown in discipline but of CIA torture techniques that have metastasized over the past 50 years like an undetected cancer inside the U.S. intelligence community. From 1950 to 1962, the CIA led secret research into coercion and consciousness that … produced a new method of torture that was psychological, not physical—best described as ‘no touch’ torture.”24

I might be done with torture, but torture was not yet done with me. So I ended up writing a new book, A Question of Torture, about the CIA’s central role in propagating such psychological techniques globally.25 At the time, the Bush administration was releasing a succession of official reports blaming the army’s lowly “bad apples” for Abu Ghraib. My controversial interpretation would not be corroborated until December 2014 when the Senate Intelligence Committee finally released a report finding the CIA responsible for serious and systemic torture. At a cost of several thousand dollars for a research assistant, my historical approach had revealed a fifty-year trail of institutional continuity that led to the post-9/11 psychological torture at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere. A decade later, the Senate committee would spend $40 million to review six million pages of classified CIA documents and reach similar, albeit more detailed and definitive conclusions.26

While the painful US debate over torture was running its course, my work on the Philippine security services was moving from the army to the police, from external defense to internal security, focusing on the role of surveillance. Reviewing documents from the American pacification of the Philippines after 1898, I made an unexpected discovery: to defeat a determined Filipino resistance, the United States formed what was arguably the world’s first surveillance state. As described in my book Policing America’s Empire, the commander of army intelligence at Manila circa 1900, Captain Ralph Van Deman, later applied lessons learned from pacifying the Philippines to establishing this country’s first internal security agency during World War I, making him “the father of U.S. Military Intelligence.”27

After he retired at the rank of major general in 1929, Van Deman compiled a quarter million files on suspected subversives that he shared with the military, the FBI, and conservative Republicans—including Richard Nixon, who used this “intelligence” to smear rivals in his California congressional campaigns. Van Deman also represented the army at a closed-door conference in 1940 that gave the FBI control over all US counterintelligence, launching J. Edgar Hoover’s thirty-year attempt to extirpate subversion, real and imagined, through pervasive surveillance and illegal agent provocateur operations involving blackmail, disinformation, and violence.28

Although memory of the FBI’s excesses had largely been washed away by the wave of reforms that followed the war in Vietnam, the terror attacks of September 2001 sparked a “Global War on Terror” that allowed the National Security Agency (NSA) to launch renewed surveillance on a previously unimaginable scale. Writing for the online journal TomDispatch in November 2009, I observed that once again coercive methods tested at the periphery of US power were being repatriated to build “a technological template that could be just a few tweaks away from creating a domestic surveillance state.” Just as the Philippine pacification of 1898 had created methods for domestic surveillance during World War I, so sophisticated biometric and cyber techniques forged in the war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq were now making a “digital surveillance state a reality, changing fundamentally the character of American democracy.”29

Four years later, Edward Snowden’s leak of secret NSA documents revealed those “few tweaks” had, in fact, been more than tweaked and the US digital surveillance state, after a century-long gestation, had finally arrived. During World War I, General Van Deman’s legion of 1,700 soldiers and 350,000 citizen-vigilantes had conducted an intense shoe-leather surveillance of suspected enemy spies among German Americans (including my grandfather, breaking into his military locker to steal “suspicious” letters his mother had written in her native German about knitting him socks for guard duty). In the 1950s, Hoover’s FBI agents tapped several thousand phones and kept suspected subversives under close surveillance, just as they did my mother’s cousin Gerard Piel, an antinuclear activist and the publisher of Scientific American magazine. Now in the Internet age, the NSA could monitor tens of millions of private lives worldwide through a few hundred computerized probes into the global grid of fiber-optic cables.

Such surveillance was by no means benign. My own writing on sensitive topics like torture and surveillance earned me, in 2013 alone, another IRS audit, TSA body searches at national airports, and, as I discovered when the line went dead, a tap on my telephone at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. If my family’s experience across the span of three generations is in any way representative, state surveillance has been an integral part of American political life far longer than we might imagine. Beyond our borders, Washington’s worldwide surveillance has become, at the cost of personal privacy, a weapon of exceptional power in a bid to extend US global hegemony far deeper into the twenty-first century.

After decades of thinking about specific aspects of American power, I was finally ready to consider the larger system that encompassed them all, to explore a distinctive form of empire—the US global presence. With the end of the Cold War in 1991, the term empire suddenly lost its subversive taint, though most historians of American foreign policy remained indoctrinated into denial. So the initial exploration of this country as an empire was largely conducted, in the early 1990s, not by the academy’s many diplomatic historians but instead by a smaller number of literary scholars who specialized in cultural or postcolonial studies.30 Then, in the aftermath of the 2001 terror attacks and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, policy specialists across the political spectrum embraced the concept of empire to ask whether or not US global power was in decline. But there was still little history, particularly comparative history, of the nature of this imperial power. At the peak moment of its global dominion, history’s most powerful empire, now commonly called the planet’s “sole superpower,” was arguably its least studied.

To address this disparity, some colleagues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where a critical perspective had survived the Cold War, launched a project on “Empires in Transition” meant to incorporate America into the comparative history of world empires. Starting in 2004, our small group quickly grew into a network of 140 scholars on four continents who participated in a series of international conferences and published two essay collections bookending the rise and decline of US global power.31

To sum up America’s rise to world power over the past 120 years, imagine three distinct phases precipitated by those endless wars: first, following the Spanish-American War, a brief yet transformative experience with colonial rule in the Caribbean and the Pacific from 1898 to 1935; next, a sudden ascent to global dominion in the decades after World War II; and, finally, a bid to extend that hegemony deep into the twenty-first century through a fusion of cyberwar, space warfare, trade pacts, and military alliances. In the century from the Spanish-American War to the end of the Cold War, Washington had developed a distinctive form of global governance that incorporated aspects of antecedent empires, ancient and modern. This unique US imperium was Athenian in its ability to forge coalitions among allies; Roman in its reliance on legions that occupied military bases across most of the known world; and British in its aspiration to merge culture, commerce, and alliances into a comprehensive system that covered the globe.

With that system came a restless, relentless quest for technological innovation that lent it a distinctive dimension. Not only did Washington strive for military superiority in the three conventional domains of air, land, and sea, but its fusion of science and industry opened new arenas for the exercise of global dominion. During the Cold War, the US intelligence community, led by the CIA and the NSA, became a supple, sophisticated instrument for projecting power on a global scale. The CIA’s attempt to penetrate communist states failed abysmally in China, Russia, and Vietnam, but the agency proved far more skilled in manipulating allies on Washington’s side of the Iron Curtain through coups and covert interventions, particularly among the myriad of new nations that emerged in Asia and Africa amid the collapse of the last of the European empires. By the end of the Cold War, clandestine operations had thus become such a critical instrument for power projection that they made up a new, fourth domain of warfare I call the covert netherworld.

During those years as well, Washington also competed in the “space race” with the Soviet Union in ways that, through the world’s first system of global telecommunications satellites, added another novel dimension to its global power. In the decades that followed, Washington would militarize the stratosphere and exosphere through an armada of unmanned drones, making space a fifth domain for great power expansion and future potential conflict.

Finally, thanks to the web of fiber-optic cables woven around the globe for the Internet, the NSA was able to shift its focus from signals intercepts in the sky to probing those cables beneath the sea for surveillance and cyberwar. In this way, cyberspace became the newest domain for military conflict. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, Washington’s bid for what it termed “full-spectrum dominance” across all six domains of warfare—both conventional (air, land, sea) and clandestine (aerospace, cyberspace, covert nether-world)—gave it a national security state of potentially exceptional strength with which to maintain its global power, despite fading economic influence, for decades to come.

The “American Century” that publisher Henry Luce had proclaimed in a Life magazine editorial in February 1941 seemed certain, until quite recently, to reach its full centennial. “As America enters dynamically upon the world scene,” Luce wrote on the eve of World War II, “we need most of all to seek and to bring forth a vision of America as a world power which is authentically American and which can inspire us to live and work and fight with vigor and enthusiasm.”32 For the next fifty years, the United States had fulfilled those aspirations, ruling over much of the world outside the Iron Curtain with a distinctive mix of cultural attraction and covert manipulation, supple diplomacy and raw force, and generous aid and grasping profits.

After the Soviet Union imploded in the early 1990s, there seemed no power on the planet that could challenge Washington’s dominion. With the country standing astride the globe like an indomitable titan and no credible challenge on the horizon, Washington’s policy gurus imagined that the “end of history” had arrived, making American-style democracy “the final form of human government.”33 Yet only a decade later, that portentous “end of history” had been swept away and history was back with a vengeance. Washington found itself in a period of imperial transition like those that had spelled the end of earlier empires in centuries past. Suddenly, we could see the shape of a new great power conflict between Washington and Beijing that could determine the course of this still young twenty-first century.

With the shock of the 9/11 terror attacks and the subsequent slide into the military miasma of Afghanistan and Iraq, there was a growing sense that America’s global power had reached its limits. In a detailed 2012 report, the National Intelligence Council, Washington’s supreme analytic body, warned: “By 2030, no country … will be a hegemonic power … largely reversing the historic rise of the West since 1750. Asia will have surpassed North America and Europe combined in terms of global power, based on GDP, population size, military spending, and technological investment. China alone will probably have the largest economy, surpassing that of the United States a few years before 2030.”34 If this prediction proves correct, then many of my baby boom generation, born at the start of the American Century, will likely be around to witness its end.

After two decades of extraordinary economic growth, in 2014 China started to reveal its strategy for challenging Washington’s hegemony. Its plans included making massive infrastructure investments that would bind Europe and Asia into a “world island,” the future epicenter of global economic power, while building military bases in the South China Sea that would sever US military encirclement of the sprawling Eurasian landmass. Refusing to cede its global dominion, the Pentagon responded to China’s challenge by shifting some strategic assets to Asia and by launching new “wonder weapons” meant to check any rival power.35

Countless unforeseen factors can, of course, subvert these grand strategies. Any number of powerful new forces can suddenly change the trajectory of world history. Projecting present trends into the future is perilously close to a fool’s errand. No methodology can possibly encompass the many moving parts of a world empire, much less the ever-changing interactions among several of these behemoths.36

Still, in the first decade and a half of this century, a few key trends already seem clear enough. While the United States enjoyed strong national unity and a bipartisan foreign policy during the first half century of its global dominion, it now faces the challenge of maintaining stability in a time of deepening social divisions, exacerbated by the slow waning of its world power. In the quarter century since the end of the Cold War, the old bipartisan consensus over foreign policy has given way to entrenched partisan divisions. While Democrats Bill Clinton and Barack Obama tried to maintain Washington’s world leadership through multilateralism and diplomacy, Republicans George W. Bush and Donald Trump have, in a patriotic reaction against a perceived loss of stature, favored unilateral action and military solutions. This conflict whipsaws the country’s foreign policy in contradictory directions, alienating allies and accelerating the decline of its power.

We are undoubtedly at the start of a major transition away from untrammeled US hegemony. If the National Intelligence Council is to be believed, then the American Century, proclaimed with such boundless optimism back in 1941, will be ending well before 2041. After a quarter century as the world’s sole superpower, Washington now faces an adversary with both the means and determination to mount a sustained challenge to its dominion. Even if Beijing falters, thanks to a decline in economic growth or a surge in popular discontent, there are still a dozen rising powers working to build a multipolar world beyond the grasp of any global hegemon.

As the patterns of world power shift in the decades to come, we will learn whether this imperial transition will be similar to any of the epochal events of the past two centuries—the global war that defeated Napoleon’s First French Empire in the early nineteenth century, the diplomacy that broke up the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires after World War I, the tempest that crushed the Axis empires during World War II, the quiet entente that marked the imperial handover from London to Washington in the 1950s, or the mass protests that shattered the Soviet Empire in the 1990s.

Whether by slow erosion or violent eruption, this ongoing shift in the balance of power bears watching. From everything I have learned over the past fifty years, we can count on one thing: this transition will be transformative, even traumatically so, impacting the lives of almost every American. In the years to come, these changes will certainly demand our close and careful attention.