The World Island and the Rise of America

For even the greatest of empires, geography is often destiny. You wouldn’t know it in Washington, though. America’s political, national security, and foreign policy elites continue to ignore the basics of geopolitics that have shaped the fate of world empires for the past five hundred years. As a result, they have missed the significance of the rapid global changes in Eurasia that are in the process of undermining the grand strategy for world dominion that Washington has pursued these past seven decades.

A glance at what passes for insider “wisdom” in Washington reveals a worldview of stunning insularity. As an example, take Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye Jr., known for his concept of “soft power.” Offering a simple list of ways in which he believes US military, economic, and cultural power remains singular and superior, he argued in 2015 that there is no force, internal or global, capable of eclipsing America’s future as the world’s premier power. For those pointing to Beijing’s surging economy and proclaiming this “the Chinese century,” Nye offered up a roster of negatives: China’s per capita income “will take decades to catch up (if ever)” with America’s; it has myopically “focused its policies primarily on its region”; and it has “not developed any significant capabilities for global force projection.” Above all, Nye claimed, China suffers “geopolitical disadvantages in the internal Asian balance of power, compared to America.” Or put it this way (and in this Nye is typical of a whole world of Washington thinking): with more allies, ships, fighters, missiles, money, and blockbuster movies than any other power, Washington wins. Hands down.1

If Nye paints power by the numbers, former secretary of state and national security adviser Henry Kissinger’s latest tome, modestly titled World Order and hailed in reviews as nothing less than a revelation, adopts a Nietzschean perspective. The ageless Kissinger portrays global politics as highly susceptible to shaping by great leaders with a will to power. By this measure, in the tradition of master European diplomats Charles de Talleyrand and Prince Metternich, President Theodore Roosevelt was a bold visionary who launched “an American role in managing the Asia-Pacific equilibrium.” On the other hand, Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic dream of national self-determination rendered him geopolitically inept, just as Franklin Roosevelt’s vision of a humane world blinded him to Stalin’s steely “global strategy.” Harry Truman, in contrast, overcame national ambivalence to commit “America to the shaping of a new international order,” a policy wisely followed by the next twelve presidents. Among the most “courageous” of them was that leader of “dignity and conviction,” George W. Bush, whose resolute bid for the “transformation of Iraq from among the Middle East’s most repressive states to a multiparty democracy” would have succeeded, had it not been for the “ruthless” subversion of his work by Syria and Iran. In such a view, geopolitics has no place. Diplomacy is the work solely of “statesmen”—whether kings, presidents, or prime ministers.2

And perhaps that’s a comforting perspective in Washington at a moment when America’s hegemony is visibly crumbling amid a tectonic shift in global power. With its anointed seers remarkably obtuse on the subject of global political power, perhaps it’s time to get back to basics, to return, that is, to the foundational text of modern geopolitics, which remains an indispensable guide even though it was published in an obscure British geography journal well over a century ago.

Halford Mackinder Invents Geopolitics

On a cold London evening in January 1904, Halford Mackinder, the director of the London School of Economics, “entranced” an audience at the Royal Geographical Society on Savile Row with a paper boldly titled “The Geographical Pivot of History.” His talk evinced, said the society’s president, “a brilliancy of description … we have seldom had equaled in this room.”3

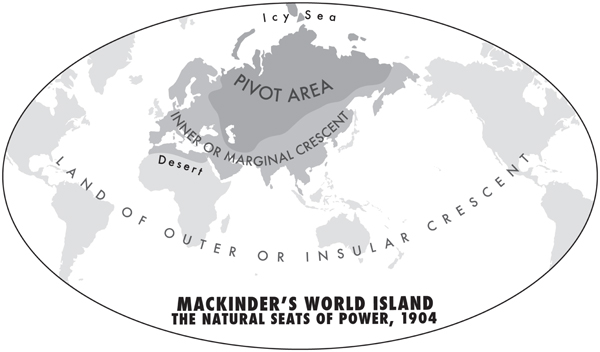

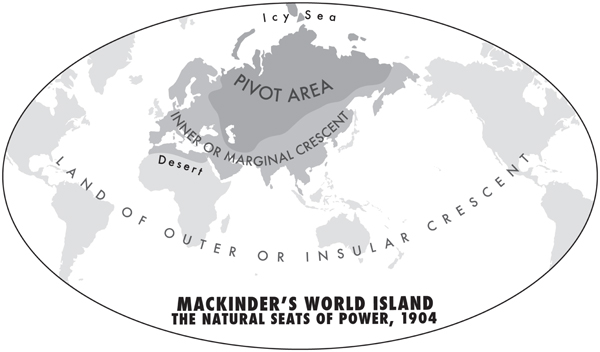

Mackinder argued that the future of global power lay not, as most British then imagined, in controlling the planet’s sea lanes but instead inside a vast landmass he called “Euro-Asia.” He presented Africa, Asia, and Europe not as three separate continents, but as a unitary landform, a veritable “world island.” Its broad, deep “heartland”—4,000 miles from the Persian Gulf to the Siberian Sea—was so vast that it could only be controlled from its “rimlands” in Eastern Europe or what he called its maritime “marginal” in the surrounding seas.4

The “discovery of the Cape road to the Indies” around Africa in the sixteenth century, Mackinder explained, “endowed Christendom with the widest possible mobility of power … wrapping her influence round the Euro-Asiatic land-power which had hitherto threatened her very existence.”5 This greater mobility, he later explained, gave Europe’s seamen “superiority for some four centuries over the landsmen of Africa and Asia.”6

Yet the “heartland” of this vast landmass, a “pivot area” stretching from the Persian Gulf across Russia’s vast steppes and Siberian forests, remained nothing less than the Archimedean fulcrum for future world power. “Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island,” Mackinder later wrote. “Who rules the World-Island commands the world.” Beyond the vast mass of that island, which made up nearly 60 percent of the Earth’s landmass, lay a less consequential hemisphere covered with broad oceans and a few outlying “smaller islands.” He meant, of course, Australia, Greenland, and the Americas.7

For an earlier generation of the Victorian age, the opening of the Suez Canal and the advent of steam shipping had, he said, “increased the mobility of sea-power relatively to land power.” But now railways could “work the greater wonder in the steppe”—a reference to a historic event that everyone in his audience that night knew well: the relentless advance of the Trans-Siberian Railroad’s track from Moscow toward Vladivostok and the Pacific Ocean. Such transcontinental railroads would, he believed, eventually undercut the cost of sea transport and shift the locus of geopolitical power inland. In the fullness of time, the “pivot state” of Russia might, in alliance with another land power like Germany, expand “over the marginal lands of Euro-Asia,” allowing “the use of vast continental resources for fleet-building, and the empire of the world would be in sight.”8

For the next two hours, as he read through a text thick with the convoluted syntax and classical references expected of a former Oxford don, his audience knew that they were privy to something extraordinary. Several stayed after his talk to offer extended commentaries. The renowned military analyst Spenser Wilkinson, the first to hold a chair in military history at Oxford, pronounced himself unconvinced about “the modern expansion of Russia,” insisting that British and Japanese naval power would continue the historic function of holding “the balance between the divided forces … on the continental area.”9

Pressed by his learned listeners to consider other facts or factors, including the newly invented “air as a means of locomotion,” Mackinder responded: “My aim is not to predict a great future for this or that country, but to make a geographical formula into which you could fit any political balance.” Instead of specific events, Mackinder was reaching for a general theory about the causal connection between geography and global power. “The future of the world,” he insisted, “depends on the maintenance of [a] balance of power” between sea powers such as Britain or Japan operating from the maritime marginal and “the expansive internal forces” within the Euro-Asian heartland they were intent on containing.10

For publication in the Geographical Journal later that year, Mackinder redrew and even reconceptualized the world map by turning the globe toward Eurasia and then tilting it northward a bit beyond Mercator’s equatorial projection. Not only did this rendering show Africa, Asia, and Europe as that massive, unitary “world island,” but it also shrank Greenland and the Americas into inconsequential marginalia.11 For Europeans, used to projections that placed their continent at the world’s center, Mackinder’s map was an innovation; but for Americans, whose big, brightly colored schoolroom maps fostered an illusory sense of their hemisphere’s centrality by splitting the Eurasian landmass into two lesser blobs, it should have been a revelation.12

Apart from articulating a worldview that would influence Britain’s foreign policy for several decades, Mackinder also created, in that single, seminal lecture, the modern science of “geopolitics”—the study of how geography can, under certain circumstances, shape the destiny of whole peoples, nations, and empires.13

That night in London was, of course, more than a hundred years ago. It was another age. England was still mourning the death of Queen Victoria. Teddy Roosevelt was America’s president. The bloody, protracted American pacification of its Philippine colony was finally winding down. Henry Ford had just opened a small auto plant in Detroit to make his Model A, an automobile with a top speed of twenty-eight miles per hour. Only a month earlier, the Wright brothers’ Flyer had taken to the air for the first time—120 feet of air, to be exact.

Yet, for the next 110 years, Sir Halford Mackinder’s words would offer a prism of exceptional precision when it came to understanding the often obscure geopolitics driving the world’s major conflicts—two world wars, a Cold War, America’s Asian wars (Korea and Vietnam), two Persian Gulf wars, and even the endless pacification of Afghanistan. The question we now need to consider is this: How can Mackinder help us understand not only centuries past but also the half century still to come?

Britannia Rules the Waves

In the age of sea power that lasted just over four hundred years—from Portugal’s conquest of Malacca in 1511 to the Washington Disarmament Conference of 1922—the great powers competed to control the Eurasian world island via the sea lanes that stretched for 15,000 miles from London to Tokyo. The instrument of power was, of course, the ship—first, caravels and men-of-war, then battleships, submarines, and aircraft carriers. While land armies slogged through the mud of Manchuria or France in battles with mind-numbing casualties, imperial navies skimmed the seas, maneuvering for the control of coasts and continents.

At the peak of its imperial power around 1900, Great Britain ruled the waves with a fleet of three hundred capital ships and thirty naval bastions—fortified bases that ringed the world island from the North Atlantic at Scapa Flow off Scotland through the Mediterranean at Malta and Suez to Bombay, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Just as the Roman Empire had once enclosed the Mediterranean, making it mare nostrum (“our sea”), so British power would make the Indian Ocean its own “closed sea,” securing its flanks with army forts along India’s North-West Frontier and barring both Persians and Ottomans from building naval bases on the Persian Gulf.

By that maneuver, Britain also secured control over Arabia and Mesopotamia, strategic terrain that Mackinder had termed “the passage-land from Europe to the Indies” and the gateway to the world island’s “heartland.” From this geopolitical perspective, the nineteenth century was, in essence, a strategic rivalry, often called “the Great Game,” between Russia “in command of nearly the whole of the Heartland … knocking at the landward gates of the Indies,” and Britain “advancing inland from the sea gates of India to meet the menace from the northwest.” In other words, Mackinder concluded, “the final geographical realities” of the modern age were land power versus sea power.14

Intense rivalries, first between England and France, then England and Germany, helped drive a relentless European naval arms race that raised the price of sea power to nearly unsustainable levels. In 1805, Admiral Nelson’s flagship, the HMS Victory, with its oaken hull weighing just 3,500 tons, sailed into the battle of Trafalgar against Napoleon’s navy at nine knots, its hundred smoothbore cannon firing 42-pound balls at a range of no more than 400 yards.

Just a century later in 1906, Britain launched the world’s first battleship, the HMS Dreadnought, its foot-thick steel hull weighing 20,000 tons, its steam turbines allowing speeds of 21 knots, and its mechanized 12-inch guns rapid-firing 850-pound shells up to 12 miles. The cost for this Leviathan was £1.8 million, equivalent to nearly $300 million today. Within a decade, half-a-dozen powers had emptied their treasuries to build whole fleets of these lethal, lavishly expensive battleships.

Thanks to a combination of technological superiority, global reach, and naval alliances with the United States and Japan, a Pax Britannica would last a full century, 1815 to 1914. In the end, however, this global system was marked by an accelerating naval arms race, volatile great-power diplomacy, and a bitter competition for overseas empire that imploded into the mindless slaughter of World War I, leaving sixteen million dead by 1918.

As the eminent imperial historian Paul Kennedy once observed, “The rest of the twentieth century bore witness to Mackinder’s thesis,” with two world wars fought over “rimlands” running from Eastern Europe to East Asia.15 Indeed, World War I was, as Mackinder himself later observed, “a straight duel between land-power and sea-power.”16 At war’s end in 1918, the sea powers—Britain, America, and Japan—sent naval expeditions to Arkhangelsk, the Black Sea, and Siberia to contain Russia’s revolution inside its own “heartland.”

During World War II, Mackinder’s ideas shaped the course of the war beyond anything he could have imagined. Reflecting Mackinder’s influence on geopolitical thinking in Germany, Adolf Hitler would risk his Reich in a misbegotten effort to capture the Russian heartland as lebensraum, or living space, for his German “master race.”

In the interwar years, Sir Halford’s work had influenced the ideas of German geographer Karl Haushofer, founder of the journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik and the leading proponent of lebensraum. After retiring from the Bavarian Army as a major general in 1919, Haushofer studied geography with an eye to preventing a recurrence of the strategic blunders that had contributed to Germany’s defeat in World War I. Later, he would become a professor at Munich University, an adviser to Adolf Hitler, and a “close collaborator” with deputy führer Rudolf Hess, his former student. Through his forty books, four hundred articles, countless lectures, and frequent meetings with top Nazi officials including Hitler, Haushofer propagated his concept of lebensraum, arguing that “space is not only the vehicle of power … it is power.” His teaching inspired what an investigator for the Nuremburg war crimes tribunal called “visions of Germany being transformed into an immense continental power and rendered impregnable against the seapower of England.” In sum, Haushofer argued that “any power which controlled the Heartland (Russia plus Germany) could control the world.” His son Albrecht, a “skilled geopolitican,” took these ideas into the heart of the Third Reich as professor of political geography at Berlin University where he also ran “a training school for members of the Nazi diplomatic service.”17

On the eve of World War II, Karl Haushofer observed that the locus of the continent’s land-sea conflict had moved east into the Pacific. “Eurasia is still unorganized and divided—hence America’s superiority,” he wrote in his Geopolitics of the Pacific Ocean. “Eurasia has no unified geopolitics. Meanwhile, both the largest sea space, the Pacific, and the second largest land space, America, are about to encounter and confront it.”18

In 1942, the führer dispatched a million men, 10,000 artillery pieces, and 500 tanks to breach the Volga River at Stalingrad and capture that Russian heartland for lebensraum. In the end, the Reich’s forces suffered 850,000 casualties—killed, wounded, and captured—in a vain attempt to break through the East European rimland into the world island’s pivotal region. Appalled by the attack on Russia, Albrecht made peace overtures to Britain, then joined the underground that tried to assassinate Hitler, and was imprisoned after hiding in the Alps. In the months before he was shot by Nazi security on the day the Allies captured Berlin, Albrecht composed mournful, metaphorical sonnets about the fiend of geopolitical power buried deep under the sea until “my father broke the seal” and “set the demon free to roam throughout the world.” A few months later, Karl Haushofer and his Jewish wife committed suicide together when confronted with the possibility of his prosecution as a senior Nazi war criminal.19

A century after Mackinder’s treatise, another British scholar, imperial historian John Darwin, argued in his magisterial survey After Tamerlane that the United States had achieved its “colossal Imperium … on an unprecedented scale” in the wake of World War II by becoming the first power in history to control the strategic axial points “at both ends of Eurasia.” With fear of Chinese and Russian expansion serving as the “catalyst for collaboration,” the United States secured sprawling bastions in both Western Europe and Japan. With these axial points as anchors for an arc of military bases around Eurasia, Washington enjoyed a superior geopolitical position to wage the Cold War against China and the Soviet Union.20

America’s Axial Geopolitics

Having seized the axial ends of the world island from Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in 1945, the United States would rely for the next seventy years on ever-thickening layers of military power to contain rival hegemons China and Russia inside that continental heartland—enjoying decades of unimpeded access to the trade and resources of five continents and thereby building a global dominion of unprecedented wealth and power. The current emerging conflict between Beijing and Washington is thus, in this sense, just the latest round in a centuries-long struggle for control over the Eurasian landmass between maritime and land powers—Spain versus the Ottomans, Britain versus Russia, and, more recently, the United States versus the Third Reich and then the Soviet Union.

Indeed, in 1943, two years before World War II ended, an aging Mackinder published his last article, “The Round World and the Winning of the Peace,” in the influential US journal Foreign Affairs. He reminded Americans aspiring to a “grand strategy” that even their “dream of a global air power” would not change the world’s geopolitical fundamentals. “If the Soviet Union emerges from this war as conqueror of Germany,” he warned, “she must rank as the greatest land Power on the globe,” controlling the “greatest natural fortress on earth.”21

Mindful of these geopolitics, the US War Department in Washington was already planning its postwar position along the Pacific littoral in ways that would correct the defensive conundrum that had dogged Washington for decades. Inspired by the naval strategist Alfred Mahan who, as early as 1890, imagined the United States as a Pacific power, Washington had established military bases in the Philippines as anchors for an expanded defensive perimeter that would stretch from Cuba through the Panama Canal to Pearl Harbor and all the way to Manila Bay. At the end of World War I, however, the Versailles peace settlement conceded the Marianas and Micronesia to Tokyo. Suddenly, the Japanese navy was in a mid-Pacific blocking position, rendering the American defense of the Philippines a strategic impossibility. That geopolitical reality doomed General Douglas MacArthur’s army to a humiliating defeat in the Battle of Bataan at the start of World War II.22

As bomber ranges increased from 1,100 miles for the B-17 at war’s start to 3,200 for the B-29 by war’s end, the War Department in Washington decided, in 1943, to coordinate its wartime liberation of the Philippines with postwar plans for two strategic bomber wings, the “Luzon Bomber Striking Force” and the “Mindanao Bomber Striking Force,” protected by twenty-six air, land, and sea bases that would ring the entire archipelago. Fearing the loss of US military protection and desperate for reconstruction aid, in 1947 Manila gave the United States a ninety-nine-year lease on twenty-three installations with unrestricted use for offensive operations.23

To clamp a vice-grip of control over the vastness of Eurasia, these Philippine bases, along with dozens more along the length of Japan, became bastions for securing the eastern end of this sprawling landmass, while US forces in Europe occupied the continent’s western axial point. With offshore military bases stretching for two thousand miles from Japan through Okinawa to the Philippines, Washington made the Pacific littoral its geopolitical fulcrum for the defense of one continent (North America) and the control over another (Eurasia).24

When it came to the establishment of a new postwar Pax Americana, first and foundational for the containment of Soviet land power would be the US Navy. Its fleets would come to surround the Eurasian continent, supplementing and then supplanting the British: the Sixth Fleet based at Naples in 1946 for the Atlantic and the Mediterranean; the Seventh Fleet at Subic Bay, Philippines, in 1947 for the Western Pacific; and the Fifth Fleet at Bahrain in the Persian Gulf since 1995.25

Next, American diplomats added a layer of encircling military alliances—from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, 1949) and the Middle East Treaty Organization (1955), all the way to the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO, 1954). NATO proved the most robust of these alliances, growing eventually to twenty-eight member nations and thereby providing a firm foundation for the US military position in Europe. By contrast, SEA-TO had only eight members, including just two from Southeast Asia, and quickly collapsed after the war in Vietnam. Absent a strong multilateral pact for Asia, Washington’s position along the Pacific littoral rested on four bilateral alliances—the ANZUS Treaty with Australia and New Zealand (1951), the Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty (1951), the US-Japan Security Treaty (1951), and the US–Republic of Korea Mutual Defense Treaty (1953).

To anchor its geopolitical position, Washington also built massive air and naval bastions at the axial antipodes of the world island—notably at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, Subic Bay Naval Station, and multiple locations in Japan. For five years until its completion in 1952, Ramstein was the largest construction site in Europe, employing 270,000 workers.26 Starting in 1952, the navy spent $170 million on a home port for its Seventh Fleet at Subic Bay—building a massive wharf for aircraft carriers, runways for a busy naval air station, and a sprawling ship repair facility that employed 15,000 Filipino workers. As home to the Thirteenth Air Force, nearby Clark Field had capacity for two hundred fighters and a bombing range bigger than the District of Columbia.27

During its postwar occupation of Japan, the United States acquired more than a hundred military facilities—largely by occupying and rebuilding imperial installations—that stretched from Misawa Air Base in the north, through Yokota Air Base and Yokosuka Naval Base in the center near Tokyo, to the Marine Air Station Iwakuni and Sasebo Naval Base in the south. With its strategic location, Okinawa had the largest concentration of American forces, with thirty-two active installations covering about 20 percent of the entire island. By 1955, the United States also had a global network of 450 military bases in thirty-six countries aimed, in large part, at containing the Sino-Soviet bloc behind an Iron Curtain that coincided to a surprising degree with Mackinder’s “rimlands” around the Eurasian landmass.28

After Soviet challenges to US control of these axial antipodes were blocked by a hot war in South Korea (1953) and a near-war in Berlin (1961), the conflict shifted to the continent’s rugged southern tier stretching for five thousand miles, from the eastern Mediterranean to the South China Sea. There the Cold War’s bloodiest battles were fought in the passageways around the massive Himalayan barrier, six miles high and two thousand miles wide—first in the east in Laos and Vietnam (1961–75) and then west-ward in Afghanistan (1978–92). With its vast oil reserves, the Persian Gulf region became the fulcrum for Washington’s position on the world island, serving for nearly forty years as the main site of its overt and covert interventions. The 1979 revolution in Iran signaled loss of its keystone position in the Gulf, leaving Washington flailing about ever since to rebuild its geopolitical leverage in the region. In the process, it would, during the Reagan years of the 1980s, simultaneously back Saddam Hussein’s Iraq against revolutionary Iran and arm the most extreme of the Afghan mujahedeen against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

It was in this context that Zbigniew Brzezinski, national security adviser to President Jimmy Carter, unleashed his strategy for the defeat of the Soviet Union with a geopolitical agility still little understood today. In 1979, Brzezinski, an émigré Polish aristocrat who had studied and frequently cited Mackinder, persuaded Carter to launch Operation Cyclone with funding that reached $500 million annually by the late 1980s.29 Its goal: to mobilize Muslim militants to attack the Soviet Union’s soft Central Asian underbelly and drive a wedge of radical Islam deep into the Soviet heartland, inflicting a demoralizing defeat on the Red Army in Afghanistan and simultaneously helping to cut Eastern Europe’s rimland free from Moscow’s orbit. “We didn’t push the Russians to intervene [in Afghanistan],” Brzezinski said in 1998, explaining his geopolitical masterstroke in the Cold War edition of the Great Game, “but we knowingly increased the probability that they would.… That secret operation was an excellent idea. Its effect was to draw the Russians into the Afghan trap.”30

Even America’s stunning victory in the Cold War could not change the geopolitical fundamentals of the world island. Consequently, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Washington’s first foreign foray of the new era would involve an attempt to reestablish its dominant position in the Persian Gulf, using Saddam Hussein’s occupation of Kuwait as its pretext.

In 2003, when the United States invaded Iraq, historian Paul Kennedy returned to Mackinder’s century-old treatise to explain this seemingly inexplicable misadventure. “Right now, with hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops in the Eurasian rimlands,” Kennedy wrote, “it looks as if Washington is taking seriously Mackinder’s injunction to ensure control of ‘the geographical pivot of history.’”31 Within a decade, however, this intervention wound up looking less like a bold geopolitical gambit and more like Germany’s disastrous decision to attack the Russian heartland. The subsequent proliferation of US bases across Afghanistan and Iraq was visibly the latest imperial bid for a pivotal position at the edge of the Eurasian heartland, akin to those British colonial forts along India’s North-West Frontier.

In the ensuing years, Washington would attempt to replace some of its ineffective boots on the ground with drones in the air. By 2011, the air force and CIA had ringed the Eurasian landmass with sixty bases for their armada of drones. By then, the workhorse Reaper drone, armed with Hellfire missiles and GBU-30 bombs, had a range of 1,150 miles, which meant that from those bases it could strike targets almost anywhere in Africa or Asia.32 To patrol this sweeping periphery, the Pentagon has also spent $10 billion to build an armada of ninety-nine Global Hawk drones with high-resolution cameras and a range of 8,700 miles.33

As it moved to a more agile global posture of smaller, scattered bases and drone strikes, Washington remained determined to maintain its axial positions at both ends of the Eurasian landmass. Although responding minimally to Russian incursions into Ukraine, the Obama administration reacted strongly to its stepped-up submarine presence in the North Atlantic. As Moscow’s revitalized fleet of forty-five attack submarines extended their patrols well beyond the Arctic Circle, Washington allocated $8.1 billion to upgrade its “undersea capabilities,” reopening a base in Iceland and adding nine new Virginia-class submarines to an existing fleet of fifty-three. “We’re back to great powers competition,” announced Admiral John M. Richardson, chief of naval operations.34 During his two terms in office, Obama also launched what was to be a protracted geopolitical pivot, from the Middle East to the Asian littoral through expanded bases and strategic forces, all aimed at checking China’s rise and its attempt to hobble Washington’s strategic position at the edge of Asia.

Decades of Debate over US Empire

Yet even as America faced the first real challenge to its hegemony in a quarter century, most Americans seemed somehow oblivious. During the endless debates of the yearlong 2016 presidential campaign, there was much criticism of trade pacts and some mention of the Middle East but surprisingly little discussion of the United States’ position in Asia or the wider world. Unmindful of the strategic significance of the alliances that long anchored America’s geopolitical position in Eurasia, Republican candidate Donald Trump wooed voters by insisting repeatedly that Tokyo should “pay 100 percent” of the costs for basing American troops in Japan and suggesting he would defend NATO allies against Russian attack only “if they fulfill their obligations to us” by putting up “more money.”35 The historian William Appleman Williams once identified such self-referential myopia as the country’s “grand illusion,” the “charming belief that the United States could reap the rewards of empire without paying the costs of empire and without admitting that it was an empire.”36

This profound, persistent ambiguity about empire among Americans was not only evident during the Cold War when Williams was writing, but dates back to the 1890s when the United States first stepped on to the world stage. For well over a century, Americans have expressed significant reservations about their nation’s rise to world power. Throughout the ever-changing crosscurrents of the country’s politics, generations of citizens in what was becoming history’s greatest empire would remain deeply conflicted over the exercise of power beyond their borders.

As the Spanish-American War of 1898 segued from military triumph into a bloody pacification of the Philippines, the Anti-Imperialist League attracted leading intellectuals who offered a withering critique of this imperial adventure. The issue of whether or not to expand loomed large in the presidential election of 1900. The most beloved writer of his generation, Mark Twain, charged that the conquest of the Philippines had “debauched America’s honor and blackened her face before the world,” and suggested the flag, Old Glory, should be modified with “white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and cross-bones.”37 Similarly, eminent Yale sociologist William Graham Sumner warned that “the inevitable effect of imperialism on democracy” was to “lessen liberty and require discipline. It will … necessitate stronger and more elaborate governmental machinery” and increase “militarism.”38

A century later, influential Americans were still worried about empire, though less about the costs of conquest than the consequences of its loss. Speaking before Congress in 2010 in the midst of a searing economic crisis, President Barack Obama warned of serious challenges to America’s global power. “China is not waiting to revamp its economy. Germany is not waiting. India is not waiting.… These nations aren’t playing for second place.” Then, in a rhetorical flourish that brought thunderous bipartisan applause, he announced, “Well, I do not accept second place for the United States of America.”39 Reprising that theme a few days later, Vice President Joe Biden rejected any comparison with fallen European empires, insisting, “We will continue to be the most significant and dominant influence in the world as long as our economy is strong.”40

As commentators cited imperial analogies, usually with Rome or Britain, to warn against America’s retreat from its global “responsibilities,”41 neoconservative historian Robert Kagan argued in an influential essay that with its unrivaled military, diplomatic, and economic clout, the United States “is not remotely like Britain circa 1900 when that empire’s relative decline began.” America alone, he insisted, can decide whether its world power will “decline over the next two decades or not for another two centuries.”42

Clearly, the word empire is a fraught one in the American political lexicon. So it is necessary to be precise at the outset: empire is not an epithet but a form of global governance in which a dominant power exercises control over the destiny of others, either through direct territorial rule (colonies) or indirect influence (military, economic, and cultural). Empire, bloc, commonwealth, or world order—they all reflect an expression of power that has persisted for much of the past four thousand years and is likely to continue into the foreseeable future. Many empires have been brutal, some more beneficent, and most a mix of both. But empires are an undeniable, unchanging fact of human history. After counting seventy empires in that history, Harvard historian Niall Fergusson noted wryly: “To those who would still insist on American ‘exceptionalism,’ the historian of empires can only retort: as exceptional as all the other sixty-nine empires.”43

Indeed, for a full half century, historians of US foreign relations subscribed strongly, almost universally, to a belief in “American exceptionalism”—the idea that this country in its beneficence was uniquely exempt from the curse of empire. During the Cold War’s ideological clash with communism, an influential group of “consensus” historians argued that the United States had avoided Europe’s class conflicts, authoritarian governments, and empires, becoming instead “an example of liberty for others to emulate.”44 To explain away his country’s brief dalliance with colonial rule after 1898, the dean of diplomatic historians, Richard W. Leopold, asserted that empire had little lasting impact on the nation because there was no territorial expansion beyond the conquest of a few islands (Puerto Rico and the Philippines); no cabinet-level department for those overseas territories, lending the project an aura of impermanence; and no increase in military spending to defend those otherwise potentially indefensible islands.45

There was, however, some notable dissent from this patriotic consensus. During the coldest of the Cold War decades, the 1950s, when pressure for affirmation of America was strong, the Wisconsin school of diplomatic history, led by William Appleman Williams and his colleague Fred Harvey Harrington, offered an unorthodox perspective on Washington’s rise to world power. In his famous dissent, The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, Williams argued that America’s “great debate of 1898–1901 over the proper strategy and tactics of … expansion” had forged a political consensus that “opposed traditional colonialism and advocated instead a policy of an open door through which America’s preponderant economic strength would … dominate all underdeveloped areas of the world.” In effect, this “classic strategy of non-colonial imperial expansion … became the strategy of American foreign policy for the next half-century,” launching Washington on a relentless extension of its informal commercial empire.46 Such expansion often gave birth to aggression, most importantly against the Soviet Union at the end of World War II when, Williams argued, Washington’s concerns over access to Eastern Europe and its markets sparked the Cold War.47

Other prominent scholars in the Wisconsin school made influential contributions as well, notably Walter LaFeber in his seminal study of late nineteenth-century expansion, The New Empire. There he explored not only the social and economic motives for overseas conquest but also its colonial outcomes in the Caribbean and Pacific.48 While Williams moved to Oregon for a quieter life at the height of Madison’s violent campus protests in 1968, his critique continued to resonate. His students—LaFeber at Cornell, Lloyd Gardner at Rutgers, and Thomas McCormick at Wisconsin—would remain active in the profession for another forty years, collaborating closely to explore America’s imperial designs and desires.49

Although this revisionist view of the nature of American power won a devoted audience in the Vietnam War years, the Wisconsin school later drew hostile fire from prominent historians. Not only was its critique of Washington’s role in the Cold War bitterly attacked but so too was its emphasis on the expansion of US economic power as an imperial phenomenon. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., called it “ludicrous” and Ernest R. May, “an artifact of the past.”50

In the quarter century since the collapse of the Soviet Union, as such patriotic passions subsided, historians and others began to confront the undeniable reality of a global behemoth that transcended past experience. Analysts of US global power, whether critics or advocates, now strained to find appropriate historical models. Some applied the Roman term imperium, meaning “dominion enforced by a single power.” Others preferred the Greek-inflected hegemony, meaning a world order that “rests on consent and cooperation, not exclusively on force and domination,” much as ancient Athens had once led a coalition of city-states.51 Recent opinion, among both pundits and scholars, separates into an imperium school that sees Washington as a latter-day Rome, the command center of a centralized empire; a hegemonic school that views America as Athens, leading a coalition of willing allies; and a conservative coterie who believe that the United States, like Great Britain in its day, should use its awesome military power to defend freedom and civilization.

On the imperium side, the critic Chalmers Johnson argued that “our militarized empire is a physical reality” manifest in over seven hundred overseas military bases that facilitated the global deployment of its armed forces and “a network of economic and political interests.”52 Reviving the Williams critique of open-door imperialism, Andrew J. Bacevich argued that both the Cold War and the war on terror were manifestations of “the American project of creating an open and integrated world.”53

Using the same concept of empire to celebrate rather than criticize, Niall Fergusson styled the United States as the much-needed successor to Great Britain’s “liberal empire,” which once used its military power to maintain a world order of free trade and civilized standards.54 “If the United States retreats from global hegemony,” Fergusson warned darkly, the planet might well plunge into “an anarchic new Dark Age; an era of waning empires and religious fanaticism; of endemic plunder and pillage in the world’s forgotten regions; of economic stagnation and civilization’s retreat into a few fortified enclaves.”55

During the economic troubles of the 1980s, historian Paul Kennedy surveyed the rise and fall of empires over the past five hundred years and issued a dire warning that the United States’ future as “the global superpower” was threatened by a growing imbalance between its expanding military commitments and its shrinking economic resources.56 But after fifteen years of sustained economic expansion, Kennedy concluded in a 2002 essay that America no longer faced the threat of such fatal “imperial overstretch.” Although spending only 3 percent of its gross domestic product on defense at the start of the war on terror, the United States accounted for 40 percent of the world’s total military expenditures. This power was manifest in the dozen lethal aircraft carriers ceaselessly patrolling the world’s oceans, each “super-dreadnought” carrying seventy “state-of-the-art aircraft that roar on and off the flight deck day and night.” A typical carrier was escorted by fourteen ships—cruisers, destroyers, attack submarines, and amphibious craft with three thousand marines ready to storm ashore anywhere in the world. After revisiting his statistics on those five hundred years of imperial history, Kennedy concluded: “Nothing has ever existed like this disparity of power; nothing. The Pax Britannica was run on the cheap.… Charlemagne’s empire was merely western European in its reach. The Roman Empire stretched further afield, but there was another great empire in Persia, and a larger one in China. There is, therefore, no comparison.” So great was America’s advantage in armaments, finance, infrastructure, and research that, said Kennedy smugly, “there is no point in the Europeans or Chinese wringing their hands about U.S. predominance.”57

In an article splashed across the cover of the New York Times Magazine on the eve of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, commentator Michael Ignatieff celebrated America’s global presence as “an empire lite, a global hegemony whose grace notes are free markets, human rights and democracy, enforced by the most awesome military power the world has ever known.”58 Harvard historian Charles Maier made a similar celebratory argument that “America has exercised an imperial hold … not merely through armed power or the CIA, but also through such institutions as the Council on Foreign Relations … and its frequent convocations” of world leaders. Their striking deference to “the political leadership of the dominant power” suggested that Washington presided over a distinctly hegemonic empire by leading a coalition of willing allies. Looking into the twenty-first century, Maier admitted somewhat ruefully that if “there are to be two or more imperial contenders, then I believe it valuable to have the United States remain one of them.”59

Between hegemony and imperium lay a more pragmatic, quintessentially conservative school that embraced the unadorned reality of Washington’s global dominion. “U.S. imperialism has been the greatest force for good in the world during the past century,” wrote the military historian Max Boot. “It has defeated the monstrous evils of communism and Nazism and lesser evils such as the Taliban and Serbian ethnic cleansing.”60 To protect the “inner core of its empire, … a family of democratic, capitalist nations,” Washington, he argued, must prepare for countless future wars along a volatile imperial periphery “teeming with failed states, criminal states, or simply a state of nature.”61 Similarly, Eliot Cohen, neoconservative counselor to George W. Bush’s State Department, argued that the “age of empire” was over, but “an age of American hegemony has begun,” and suggested that “U.S. statesmen today cannot ignore the lessons and analogies of imperial history” if they were to put together the coalitions of allied states required for successful global governance.62

In short, analysts across the political spectrum had come to agree that empire was the most appropriate word to describe America’s current superpower status. At the close of the Cold War even Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., counselor to presidents, critic of Williams, and liberal historian par excellence, conceded the imperial nature of the American stance in the world: “Who can doubt that there is an American empire?—an ‘informal’ empire, not colonial in polity, but still richly equipped with imperial paraphernalia: troops, ships, planes, bases, proconsuls, local collaborators, all spread around the luckless planet.”63

In the end, facts simply overcame ideology. Calling a nation that controls nearly half the planet’s military forces and much of its wealth an “empire” became nothing more than fitting an analytical frame to appropriate facts.64 From Boot on the right to Bacevich in the political center, a surprising consensus among established scholars of US foreign policy had formed. The question was no longer whether the United States was an empire, but how Washington might best preserve or shed its global dominion.65

Yet if we step back a bit from this fifty-year debate and the decades of denial that went with it, there has been surprisingly little time for much genuine analysis of America’s global dominion. Compared to the countless books and articles that crowd library shelves covering every imaginable aspect of European colonial rule, there is still surprisingly little serious study of history’s most powerful empire. With remarkably few exceptions, all these commentators seemed unaware of the geopolitics that had facilitated America’s ascent to global hegemony and may yet play a critical role in its decline. At a moment when Washington is facing the first serious challenges to its dominion in seventy years, it seems timely to ask: What is the character of this US empire? What attributes did it acquire during its ascent, how did it exercise global dominion, and what forces might precipitate its decline?

Addressing such questions is a tricky business. Empires are the most elusive, complex, and paradoxical of all forms of governance—strong yet often surprisingly fragile. At their peaks, empires can crush rival powers or curb subordinate states, yet their power is surprisingly vulnerable to erosion, to simply slipping away. Unlike conventional states whose defense, if well managed, is an organic, cost-effective extension of civil society, empires face exceptional costs in mounting risky military operations and maintaining a costly overseas presence. All modern empires are alike in the fundamental facts of their dominion over others. Yet in their particular exercise of power and policy, each empire is distinct.

Over the past five hundred years, empires have grown either through continental or overseas expansion. Continental empires (Hapsburg Europe, Mughal India, China, Russia, and the United States before 1867) spread by the overland conquest of contiguous territories that usually, though not always, centralized imperial governance within a unitary state. By contrast, maritime empires (Great Britain, the Netherlands, Spain, post-Napoleonic France, and the United States after 1898) necessarily decentralized their far-flung overseas rule through surrogate states called variously colonies, protectorates, dominions, mandates, trust territories, occupied lands, or even allies.66

From 1500 onward, each century brought a new layer to Europe’s overseas expansion, culminating in the late nineteenth century when half-a-dozen powers carved up Africa and Asia.67 Then, after four centuries of relentless imperial expansion that encompassed half of humanity, Europe’s overseas empires were all erased from the globe in just a quarter of a century, giving way between 1947 and 1975 to nearly a hundred new nations, over half of today’s sovereign states.

In the twenty years after World War II, the population of the British Empire fell from seven hundred million to only five million in conjunction with the full-scale appearance of the United States on the world stage.68 Over the past 120 years, Washington has moved to global power through three distinct phases, each one sparked by wars large and small. Stepping onto that stage for the first time during the Spanish-American War of 1898, America acquired a string of tropical islands stretching for 10,000 miles from the Atlantic to the Western Pacific, which plunged it into the transformative experience of colonial rule. Then, in the decades after World War II, it ascended suddenly to global dominion amid the collapse of a half-dozen European empires and the start of the Cold War with a rival global hegemon, the Soviet Union. Most recently, using technologies developed for the war on terror, Washington is making a determined bid to extend its dominion as the world’s sole superpower deep into the twenty-first century through a fusion of cyberwar, space warfare, trade pacts, and military alliances.

Empire of Tropical Islands

Small though it was, the Spanish-American War had large and lasting consequences. It took just three months and caused only 345 American combat deaths, yet it changed America from an insular, inward-looking nation into a colonial power with island territories that extended 7,000 miles beyond its shores. Not only did this scattered empire require a mobile army and a blue-water navy but it also helped foster the modernization of the federal government.

After three years of diplomatic tensions over Spain’s harsh pacification of the Cuban revolution, the explosion of the battleship USS Maine in Havana Harbor in February 1898 sparked hostilities that were greeted with a burst of patriotic frenzy across America. During the fifteen weeks of war, the navy, with its modernized fleet, quickly sank two antiquated Spanish squadrons in Cuba and the Philippines. The regular army, numbering only 28,000 men, had to mobilize National Guard units and volunteer regiments to reach the requisite strength of 220,000 troops. The fighting in Cuba was comparatively bloody, with 1,400 American casualties in the capture of Santiago alone. But Philippine revolutionary forces had already confined Spanish troops inside Manila by the time the first army transports arrived, making the capture of that capital a virtual victory parade. This easy triumph was, however, followed by four years of demoralizing pacification efforts. In the end, it took 75,000 troops to defeat the nascent Philippine republic and establish colonial rule.

With the annexation of Hawaii in 1898 and the acquisition of the Panama Canal Zone in 1903, the United States suddenly had an island empire that stretched along the Tropic of Cancer nearly halfway around the globe. Washington then developed a distinctive form of imperial rule for its new colonies in the Canal Zone, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines that left a lasting imprint on governance, at home as well as abroad.

Eschewing the visible grandeur of the great European empires, the United States ruled its disparate arc of islands through a nimble nexus of public-private alliances. Lacking a European-style colonial ministry, Washington held its overseas territories lightly through a small Bureau of Insular Affairs buried in the bowels of the War Department, while outsourcing overseas rule to low-cost surrogate governments in Manila and San Juan. Instead of dedicated colonials such as the legendary British or Dutch savants who trained at Oxford and Leiden for lifelong colonial careers, American overseas territories relied on short-term consultants and contractors, experts like urban planner Daniel Burnham and forester Gifford Pinchot who framed templates for colonial policy. Within a few years of capturing Manila in 1898, the US colonial state had mobilized a transitory A-to-Z army of consultants in fields ranging from agronomy to zoology.69

The omnipresent yet invisible architect of this unique American imperial state was Elihu Root, a New York lawyer who served successively as secretary of war and secretary of state from 1899 to 1909. As the prototype of the “wise man” who shuttles between corporate law offices in New York and federal posts in Washington, Root formalized this system of ad hoc imperial rule by reorganizing key elements of the government and later establishing a network of public-private linkages as president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (1910–25) and founder of the Council on Foreign Relations (1921). Unlike Europe’s closed policymaking by cabinet and civil servants captured in those metonyms Whitehall or Quai d’Orsay, Washington’s foreign policy formation would operate as “an empire without an emperor,” reaching consensus through a “political free-for-all—parties, interest groups, entrenched bureaucracies, and the media.”70

In this first phase of imperial evolution, those running America’s scattered empire of islands conducted ad hoc experiments in policing, public health, and national defense that would have a significant impact on the development of the federal bureaucracy. On the eve of empire in 1898, the United States had what one landmark study called a “patchwork” or weak state with a loosely structured administrative apparatus, leaving ample room for the innovation and modernization that came, with stunning speed, in these imperial decades.71 Ruling over subjects instead of citizens with civil rights, these colonies became laboratories for the perfection of state power—both the control over nature and the coercion of natives. Important innovations in governance and environmental management would migrate homeward from the imperial periphery, expanding the capacities of America’s fledgling federal government.72

In Manila, the new colonial regime, confronted with intractable Filipino resistance, married advanced US information technologies to centralized Spanish policing to produce a powerful hybrid, the Philippine Constabulary, whose pervasive surveillance slowly suffocated both the armed resistance and political dissent. Through a small cadre of constabulary veterans, this innovative experiment in police surveillance migrated homeward during World War I to serve as a model for a nascent domestic security apparatus.

To cut a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, America’s supreme imperial triumph, the United States faced almost insurmountable challenges in civil engineering and public health. During the ten years of construction, the canal became the world’s most costly civil engineering project, moving mountain-sized excavations four times those needed to build the Suez Canal. The result was an engineering marvel that would perform flawlessly for the next century, with artificial lakes, electrical tow trucks, and precision locks that transported both tramp steamers and behemoth battleships, accident free, between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. To control the yellow fever that had defeated an earlier French attempt to cut a canal across Panama’s isthmus, American officials eradicated almost all the mosquito breeding pools left by that country’s torrential tropical rains. This new expertise in public health was then applied successfully to military bases across the American South and later would play a part in the formation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.73

In this age of empire, the American conquest of cholera, malaria, and yellow fever made the man of science into a new kind of hero—notably, Walter Reed, who identified mosquitoes as the means of yellow fever transmission in Havana; William Gorgas, who conquered the same scourge in Cuba and Panama; and Walter Heiser, who purged cholera from Manila.74 Indeed, General Leonard Wood’s transformation of Santiago de Cuba from “its reeking filth, its starvation, its utter prostration” into a “clean, healthy, orderly city” catapulted this obscure army surgeon from a provincial command to the governor-generalship of Cuba and consideration for the presidency.75

Empire transformed the military. Amphibious operations spanning half the globe and the protracted pacification of the Philippines had a lasting impact on the army’s overall organization and command. From America’s founding, national defense had been the responsibility of a small standing army backed by state militia. The conquest of a sprawling overseas empire, however, changed these military realities. As secretary of war in these challenging years, Elihu Root reformed the army’s antiquated structure, creating a centralized general staff and a modern war college, while expanding professional training for officers at every echelon. As a result, a modern imperial army, shorn of its traditional mission of domestic defense, took form.

Empire also challenged the basic design of national defense, pushing America’s frontiers far beyond the chain of harbor fortifications along the eastern seaboard that had been the nation’s front lines for a full century. That insular mindset was fully replicated even in the first major modernization of the military under the Navy Act of 1890, which produced only a defensive fleet of “short-range torpedo boats” and “sea-going coastline battleships.”76 Indeed, Congress restricted their range by limiting their coal capacity. Now, however, to defend a far-flung empire, Washington removed its “range restrictions on battleships” and in 1906 started construction of the “most powerfully armed and longest-range battleships afloat.” To announce the country’s arrival as a world power, President Theodore Roosevelt sent that “Great White Fleet” of sixteen battleships on an epic voyage that, as he said to the sailors upon their return in 1909, had “steamed through all the great oceans” and “touched the coast of every continent.” They were, he told them, “the first battle fleet that has ever circumnavigated the globe.” Within four years, the United States had launched an impressive armada of thirty-nine dreadnought-class battleships, including the USS Pennsylvania, which was three times the size of the older coastal warships.77

Empire, in other words, pushed American defenses deep into the world’s oceans, requiring its first sustained projection of military power beyond its borders. In addition to a global navy, Washington now had its first experience of overseas military bases. Starting in 1907, it used scarce funds to fortify Pearl Harbor, the start of a long-term creation of an expansive Alaska–Hawaii–Caribbean defensive perimeter. When the Panama Canal finally opened in 1914, Woodrow Wilson tried to secure the country’s southern flank by an escalating set of military interventions in the Caribbean and Central America—at Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933, Veracruz in 1914, Haiti from 1915 to 1934, and the Dominican Republic from 1916 to 1924. By 1920, the United States had a half-dozen major installations, with troops permanently deployed at them, stretching halfway round the globe—including a naval base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba; army posts in Puerto Rico; coastal artillery at the entrances to the Panama Canal; the Pacific Fleet’s home port at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii; and the Asiatic Fleet’s headquarters at Manila Bay (with a nearby army base at Clark Field).

Ascent to Global Dominion

World War II and the Cold War transformed Washington into the preeminent world power and plunged it into an epochal struggle for global dominion with the Soviet Union. In marked contrast to the glorious little war against Spain, World War II was a global firestorm that left more than fifty million dead, swept away the Axis empires that ruled much of Eurasia, and exhausted the European imperial powers. By mobilizing sixteen million troops for combat and expanding its manufacturing base for war production, America emerged from that conflagration as a global superpower in a ruined world—its navy master of the oceans, its armies occupying much of Asia and Europe, and its expanded economy by far the world’s largest.

The aftermath of war only amplified its global power. Although a rival Soviet Empire had acquired a dozen satellite states in Eastern Europe and a communist revolution soon closed China to the West, the rapid postwar decolonization of Europe’s overseas empires opened nearly half of humanity to US influence. Those fading dominions became the foundation for an expanding American presence, allowing Washington to extend its hegemony across four continents with surprising speed and economy of force. Despite its rapid retreat, the British Empire left behind both models and methods that would influence this emerging hegemony.

At its peak circa 1900, Britain had managed its global empire with an effective array of hard and soft power, both the steel of naval guns and the salve of enticing culture. With strong fiscal fundamentals, Great Britain would dominate the world economy through London’s unequaled foreign investments of £3.8 billion, the country’s trade treaties with sovereign states, and global economic leadership through the gold standard and the pound sterling. Multilingual British diplomats were famously skilled at negotiating force-multiplier alliances with other major powers, including at various times France, Japan, Russia, and the United States, while ensuring its commercial access to secondary states like China and Persia that made up its informal empire.78 Its colonial officers were no less skilled at cultivating local elites from Malay sultans to African chiefs that enabled them to rule over a quarter of the globe with a minimum of military force. Both forms of British diplomacy were eased by the cultural appeal of the English language, highlighted through its literature, the Anglican religion, sports (cricket, rugby, soccer, and tennis), and mass media (Reuters news service, newspapers such as the Times, and the later BBC Radio).

As the steel behind this diplomacy, the British navy controlled maritime chokepoints from Gibraltar through the Suez Canal to the Straits of Malacca.79 Reflecting British innovation, its industries built the world’s first true battleship, the earliest tanks, and a diverse modern arsenal. With a standing army of only 99,000 men, its entire defense budget consumed just 2.5 percent of Britain’s gross domestic product, an extraordinary economy of global force.80

Britannia may have ruled the waves, but when it came ashore for either formal or informal rule it needed local allies who could serve as intermediaries in controlling complex, often volatile populations. These “subordinate elites”—so essential to the rise of any empire—can also precipitate its decline if they move into opposition. With its contradictory motto “Imperium et Libertas,” the British Empire necessarily became, as the London Times said in 1942, “a self-liquidating concern.”81 Indeed, historian Ronald Robinson has famously argued that British imperial rule ended “when colonial rulers had run out of indigenous collaborators,” with the result that the “inversion of collaboration into noncooperation largely determined the timing of decolonization.”82 The support of these local elites sustained the steady expansion of the British Empire for two hundred years, just as their later opposition assured its rapid retreat in just twenty more.

At the start of its rise to dominance after 1945, the United States had a comparable array of assets for the exercise of global dominion. Although Washington had no counterpart to the Colonial Office and would never admit to possessing anything like the British Empire, it quickly assembled a formidable bureaucratic apparatus for the exercise of world power.

Militarily, Washington had a brief monopoly on nuclear weapons and a navy of unprecedented strength. Diplomatically, it was supported by allies from Europe to Japan, an informal empire in Latin America secured by the Rio mutual-defense treaty of 1947, and an official anticolonial foreign policy that eased relations with the world’s many emerging nations. The foundation for all this newfound power was the overwhelming strength of the American economy. During World War II, America’s role as the “arsenal of democracy” meant massive industrial expansion, no damage to domestic infrastructure given that fighting only occurred elsewhere, and comparatively light casualties—four hundred thousand war dead versus seven million for Germany, ten million for China, and twenty-four million for Russia. While rival industrial nations struggled to recover from the ravages of history’s greatest war, America “bestrode the postwar world like a colossus.” With the only intact industrial complex on the planet, the US economy accounted for 35 percent of gross world output and half of its manufacturing capacity.83

At the end of World War II, the United States invested all this prestige and power in forming nothing less than a new world order through permanent international institutions—the United Nations (1945), the International Monetary Fund (1945), and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947), predecessor to the World Trade Organization.84 Continuing and deepening its commitment to the rule of law for resolution of disputes among nations, Washington convened international tribunals at Nuremburg and Tokyo to try the Axis leaders. It also helped establish the International Court of Justice at The Hague, empowered to issue rulings for enforcement by the UN Security Council.85 Moving beyond London’s ad hoc economic leadership, Washington forged formal international controls at the Bretton Woods conference of forty-four allied nations in 1944 to direct and dominate the global economy through the IMF and the World Bank. Despite such exceptional internationalism, the US imperium exhibited many essential attributes of its British and European predecessors. In the years that followed, Washington built “a hierarchical order with liberal characteristics” based on “multilateral institutions, alliances, special relationships, and client states.”86

It was the Cold War that translated all this influence into an architecture for the actual exercise of world power. Within a decade, Washington had built a potent four-tier apparatus—military, diplomatic, economic, and clandestine—for the maintenance of its expansive hegemony. At its core was the unmatched military that circled the globe with hundreds of overseas bases, a formidable nuclear arsenal, massive air and naval forces, and client armies. Complementing all this steel was the salve of an active worldwide diplomacy, manifest in close bilateral ties, multilateral alliances, economic aid, and cultural suasion. Just as America’s public sector had long created conditions for private prosperity at home, so its global extension promoted trade and security pacts that allowed its burgeoning multinational corporations to operate profitably. Adding a distinct, even novel dimension to US global power was a clandestine fourth tier that entailed global surveillance by the NSA and covert operations on five continents by the CIA, manipulating elections, promoting coups, and, when needed, mobilizing surrogate armies. Indeed, more than any other attribute, it is this clandestine dimension that distinguishes US global hegemony from earlier empires.

From the beginning, military power was at the heart of America’s global presence. The three thousand installations its armed forces had operated during World War II shrank rapidly in the postwar demobilization to just ninety-eight overseas air and naval bases. But with the start of the Cold War in the late 1940s, Washington shelved its plans for a largely hemispheric defense and began acquiring hundreds of foreign military bases.87 In geopolitical terms, Washington had become history’s most powerful empire because it was the first, after a millennium of incessant struggle, to control “both ends of Eurasia.”88 With 2.6 million active-duty troops in 1958, its military could maintain 300 overseas installations, many of them ringing that landmass from Britain through Southeast Asia to Japan. Its navy had 2,650 ships in service, including 746 warships, as well as 7,195 combat aircraft; the air force had nearly 15,000 bombers, fighters, and transports.89

By 1960, the Pentagon also had built a triad of nuclear weapons that constituted “a virtually invulnerable strategic deterrent for decades to come.” With the launch of the USS George Washington in 1959, the navy’s new squadron of five nuclear-powered submarines cruised the ocean depths incessantly, each outfitted with sixteen nuclear-armed Polaris missiles. All of the navy’s fourteen attack carriers, including the new atomic-powered USS Enterprise, were equipped for nuclear strikes. By 1960 as well, the Strategic Air Command had 1,700 intermediate- and long-range bombers ready for nuclear payloads, including six hundred of the behemoth B-52s with a range of 4,000 miles. The air force had also developed the Atlas and Titan ballistic missiles that could carry nuclear warheads over 6,000 miles to their targets.90

To soften all this abrasive hard power, Washington formed the Voice of America (1942) and Radio Free Europe (1949) for worldwide radio broadcasts, supplementing the undeniable global appeal of the Hollywood film industry. Culturally, the United States exceeded Britain’s former influence thanks to its feature films, sports (basketball and baseball), and news media (newspapers, newsreel, and radio).

Both global regimes, British and American, promoted a “liberal international order” founded on free trade, free markets, and freedom of the seas.91 By putting its Philippine colony on a path to independence in 1935, Washington had ended a brief flirtation with formal empire; but its later global hegemony seemed similar to Great Britain’s informal imperial controls over countries like China and Persia.92 Just as British diplomats were skilled at negotiating alliances to confine rivals France and then Germany to the European continent, so Washington contained the Soviet Union and China behind the Iron Curtain through multilateral alliances that stretched across the Eurasian landmass.

Yet there were also some significant differences in the ways London and Washington exercised global power. After completing his ten-volume history of human civilizations in 1961, Arnold Toynbee observed that the “American Empire” had two features that distinguished it from Great Britain’s: military bases galore and its emphasis on offering generous economic aid to allies. Following the Roman practice of respecting “the sovereign independence” of weaker allies and asking only for a “patch of ground for … a Roman fortress to provide for the common security,” Washington sought no territory, instead signing agreements for hundreds of military bases on foreign soil. The half-dozen naval bastions that the United States had acquired in 1898 grew into a matrix of three hundred overseas bases in 1954 to nearly eight hundred by 1988. In addition, in a policy “unprecedented in the history of empires,” said Toynbee, America was making “her imperial position felt by giving economic aid to the peoples under her ascendancy, instead of … exploiting them economically.”93 Indeed, in the aftermath of World War II the State Department added an economic development branch, starting with the Economic Cooperation Administration to administer the Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of Europe, and then expanding, after 1961, into a wider global effort through the Agency for International Development.

With the accelerating pace of decolonization during the 1950s, the administration of President Dwight Eisenhower was forced to develop a new system of global dominion involving a worldwide network of national leaders—autocrats, aristocrats, and pliable democrats. In effect, the fulcrum for imperial controls had moved upward from the countless colonial districts to the national capitals of a hundred new nations. From his experience commanding allied forces during World War II, President Eisenhower revitalized the national security apparatus. Under the National Security Act of 1947, Washington had already forged the basic instruments for its exercise of global power—the Defense Department, the air force, the National Security Council (NSC), and the CIA. Through parallel changes in signals intelligence, the NSA emerged by 1951, completing the apparatus of covert power. Under Eisenhower, an expanded NSC would serve as his central command and brain trust for fighting the Cold War, meeting weekly to survey a fast-changing world and plan foreign policy. At the same time, the expanding CIA became his executive strike force for securing the new system of subordinate elites. With experienced internationalists Allen Dulles heading the CIA and John Foster Dulles at State, the security agencies, filled with veterans of World War II, proved apt instruments for implementation of these expansive policies.

After shifting the CIA’s focus from an attempt to penetrate the Soviet bloc, which had failed badly, to controlling the emerging nations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, which succeeded all too brilliantly, Eisenhower authorized 170 major covert operations in forty-eight nations during his eight-year term. In effect, clandestine manipulation became Washington’s preferred mode of exercising old-fashioned imperial hegemony in a new world of nominally sovereign nations. In industrial societies, the agency cultivated allies with electoral cash, cultural suasion, and media manipulation, thereby building long-term alliances with the Christian Democrats in Italy, the Socialist Party in France, and above all the ruling Liberal Democratic Party in Japan, recipient of “millions of dollars in covert C.I.A. support.” In the developing world, the agency brought compliant leaders to power through a string of coups from Iran in 1953 to the Congo and Laos in 1960. Under the Eisenhower administration’s Overseas Internal Security Program, the CIA also served as lead agency in strengthening the repressive capacity of Washington’s Third World allies, creating secret police units for a dozen such states and, in 1958 alone, training 504,000 police officers in twenty-five nations.94

During these Cold War years, the United States favored military autocrats in South America, monarchs across the Middle East, and a mix of democrats and dictators in Asia. In a top-secret analysis of Latin America in 1954, the CIA suggested “long-standing American concepts of ‘fair play’ must be reconsidered” if the United States were to halt the region’s move toward “irresponsible and extreme nationalism, and immunity from the exercise of U.S. power.” In a logic that would guide its dominion for the next forty years, Washington would quietly set aside democratic principles for a realpolitik policy of backing reliable pro-American leaders. According to a compilation at Carnegie Mellon University, between 1946 and 2000 the rival superpowers intervened in 117 elections, or 11 percent of all the competitive national-level contests held worldwide, via campaign cash and media disinformation. Significantly, the United States was responsible for eighty-one of these attempts (70 percent of the total)—including eight instances in Italy, five in Japan, and several in Chile and Nicaragua stiffened by CIA paramilitary action.95

In Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, US military aid increased the institutional strength of local armed forces while American advisers trained more than three hundred thousand soldiers in seventy countries during the quarter century after World War II, acquiring access to this influential elite in emerging nations worldwide. Having formally established in 1968 that “Latin American military juntas were good for the United States,” the CIA supported the right-wing leaders of eleven such nations with intelligence, secret funds, and military aid. When civilian leaders became disruptive, Washington could help install a sympathetic military successor, whether Colonel Joseph Mobutu in Congo, General Suharto in Indonesia, or General Augusto Pinochet in Chile. As its chief of station in Turkey put it, the agency saw every Muslim leader in the Middle East who was not pro-American as “a target legally authorized by statute for CIA political action.” The sum of these policies fostered a distinct global trend between 1958 and 1975—a “reverse wave” away from democracy, as military coups succeeded in more than three dozen nations, a full quarter of the world’s sovereign states.96

As economic competitors grew rapidly in the prosperous years after World War II, the US share of the world’s gross product slipped from an estimated 50 percent in 1950 to only 25 percent by 1999.97 Even so, at the close of the Cold War, American multinational corporations were still the engines of global growth, its inventors led the world in patents, and its scientists had won over half the Nobel Prizes.98

Sustained by this economic and scientific strength, the military then maintained more than 700 overseas bases, an air force of 1,763 jet fighters, an armada of over 1,000 ballistic missiles, and a navy of 600 ships, including 15 nuclear carrier battle groups—all linked by the world’s only global system of communications satellites.99 Testifying to the success of this strategy, the Soviet Empire imploded circa 1991 amid a coup and secession of satellite states but without a single American shot fired. By then, however, global defense was consuming a heavy 5.2 percent of the country’s gross domestic product—twice the British rate at its peak.100

Securing the American Century

Just as the conjuncture of World War II and the Cold War made America a nuclear-armed superpower, so the war on terror developed new technologies for the preservation of its global hegemony via space, cyberspace, and robotics, levitating its military force into an ether beyond the tyranny of terrestrial limits.

In the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks, Washington pursued perpetrators across Asia and Africa through an expanded information infrastructure with digital surveillance, biometric identification, and agile aerospace operations. After a decade of this war with its voracious appetite for information, a 2010 Washington Post investigation found that the intelligence community had fleshed out into a veritable “fourth branch” of the federal government—a national security state with 854,000 vetted officials, 263 security organizations, and over 3,000 intelligence units.101

Though stunning, these statistics only skimmed the visible surface of what had become history’s largest and most lethal clandestine apparatus. According to NSA documents that Edward Snowden leaked in 2013, the nation’s sixteen intelligence agencies had 107,035 employees and a combined “black budget” of $52.6 billion, equivalent to 10 percent of the vast defense budget.102 By sweeping the skies and penetrating the World Wide Web’s undersea cables, the NSA was capable of capturing the confidential communications of any leader on the planet while monitoring countless millions of their citizens. For classified paramilitary missions, the CIA and its Special Activities Division also had access to the Pentagon’s Special Operations Command, with 69,000 elite troops (rangers, SEALs, air commandos) and their agile arsenal.103 Adding to this formidable paramilitary capacity, the CIA operated thirty Predator and Reaper drones responsible, from 2004 to 2016, for 580 strikes in Pakistan and Yemen with at least 3,080 deaths.104 In effect, this covert dimension had grown from a distinctive feature of US global hegemony back in the 1950s into a critical, even central factor in its bid for survival.