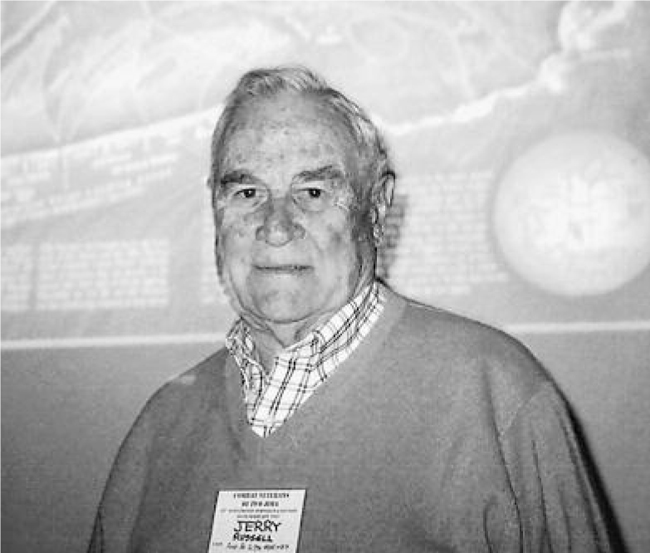

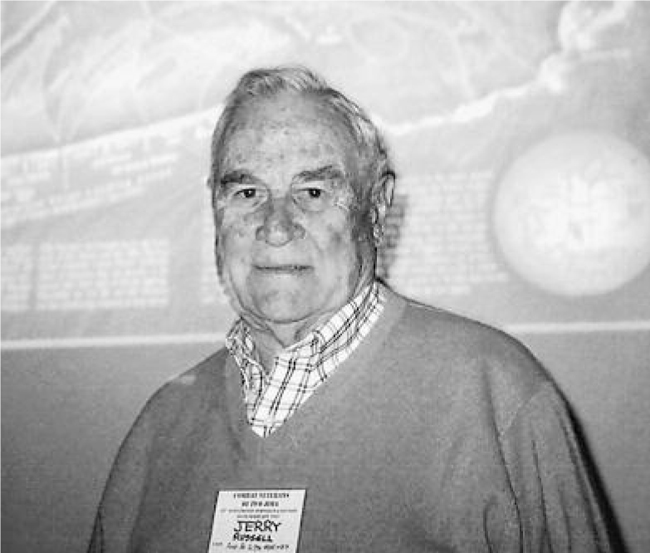

Gerry Russell, eighty at the time, standing in front of a situation map of the island at the annual Combat Veterans of Iwo Jima Symposium in Alexandria, Virginia, on February 17, 2007.

Battalion Commander

Twenty-seventh Marines, Fifth Marine Division

The most vivid memory I would mention out of all that time was the flies and the smell of the dead. That’s something they don’t mention in documentaries, but boy, when you have that many bodies all over the place, it’s sometimes days and days before they can bring them out.

Gerry Russell, eighty at the time, standing in front of a situation map of the island at the annual Combat Veterans of Iwo Jima Symposium in Alexandria, Virginia, on February 17, 2007.

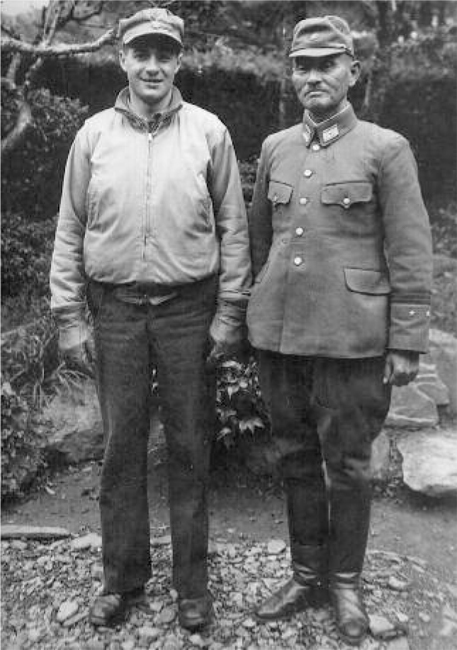

Major Gerald F. Russell accepts the surrender of the Tsushima Islands in Japan from Lieutenant General Bukei Nagasi in November 1945.

I first learned it was possible for a civilian to visit Iwo Jima from Colonel Harvey “Barney” Barnum, USMC (Ret.), who directed me to Military Historical Tours, founded and operated by another former Marine colonel, Warren Wiedhahn, in Alexandria, Virginia. I signed up for the Iwo trip and went down to Virginia to check the place out. Colonel Wiedhahn managed to have on hand Gerry Russell, one of three battalion commanders from the Iwo campaign who were still alive. Russell had worked for Penn State in State College, Pennsylvania, for many years, and it turned out he knew Joe Paterno, the Penn State football coach, very well. Russell and I had a long, satisfying visit in Colonel Wiedhahn’s offices.

“I grew up outside of Providence, Rhode Island, and went to La Salle Academy, a Christian Brothers school, and ran track, the thousand yards, indoors. I won the national championship in a race in Madison Square Garden, and by virtue of that I got a scholarship to Boston College. They had me do an extra year, redshirting, although they didn’t call it that. [Redshirting means holding an athlete back from intercollegiate competition his or her first year, so it takes five years to graduate instead of four. This way the participant has a year to get bigger and stronger before entering competition.]

“I majored in history, prelegal, and graduated in 1940. Law was my intention, and I applied for Harvard Law School and Boston College Law School. I was accepted into both, and my goal was to get enough funding somehow to go to Harvard. If not, I knew I could make it at BC.

“Then an interesting thing happened: I had an old Jesuit priest for an adviser. His name was Father Finnegan. He said, ‘You know, you’re a college graduate, and you’re single. This guy Roosevelt wants to get us into a war, and you’re going to be the first to go. They’re going to pass a draft law.’ And he said, ‘What you should do is try to get into one of these officer reserve programs in the Army or the Navy and then go through and get the commission, and then, if they don’t need you, you can just sit and go through school. They’ll know they have you.’

“Well, I had some interest in the Marine Corps, so I wrote to the commandant, Major General Thomas Holcomb—this was early summer 1940—and told him what a splendid prospect I was for an officer. I got a response back quite quickly saying, ‘We don’t want you.’ I said, ‘Well, I guess that’s that.’ But then I get another letter from the same outfit saying we’re going to start a program. If you’re still interested, fill out this form. So I filled it out and was immediately sworn in. I was ordered to Quantico in October of 1940 as part of the very first officer candidate class the Marine Corps ever had.

“Up to that time the Marine Corps would get officers from the Naval Academy or from excess of the various Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps classes around the country. There hadn’t been much opportunity for military advancement during the Depression years. The Marines usually got their number one choice because things were so limited.

“The Quantico program was envisioned as nine months, three months as a private first class, three months as a reserve second lieutenant in a classroom environment, then three months of duty with the troops. The fine print said you could go inactive subject to call if the exigencies of the time no longer required your services. I was actually in the first platoon of the first company in the candidates’ class. They brought some drill instructors up from Parris Island, and those guys’ attitude was: These men are going to be pushing us around one of these days; let’s get ’em now. Actually their goal was to make us good Marine officers, and they wanted us to be tough. That three months we were really on the go all the time. It was not unusual for them to break us out late in the evening and have us run five miles in skivvy drawers holding the rifle at high port, you know, all kinds of things. Sometimes we would either march or be trucked over to the Manassas battlegrounds. I think a lot of our tactical problems were based on some of the action that had transpired there during the Civil War, so that was pretty interesting.

“I think we ended up with about two hundred commissioned on 20 February 1941. We were supposed to be commissioned on the first, but the Department of the Navy decided to short-tour the Naval Academy class, so they would be ahead of us on the lineal list, which was very important. They were commissioned on the seventh, and we were delayed until the twentieth.

“We stayed right there for three months after that, until the month of May, and learned tactics in the classroom. Some of my classmates went to troops immediately because the Marine Corps had been so very short of officers. They needed artillery officers. We had base defense units that needed officers. They even had a barrage balloon outfit that needed officers.

“I was selected to go to artillery school. At that point there was no First Marine Division or Second Marine Division. There was no Camp Lejeune, no New River. They hadn’t even acquired it yet. I’m sure they were in process. The Fifth Marines was a battalion in Quantico. The Seventh Marines were at the Charleston Navy Yard, and I think the First Marines were at Norfolk. They were not the huge outfits that they later became.

“The Eleventh Marines, the artillery, was situated at Parris Island, so my first duty with troops was at Parris Island, probably August or September. After New River was acquired, we went up there, where the First Division was beginning to form as various units were brought in. The artillery was placed at Courthouse Bay. Of course all the roads were dirt, and the vehicles that were the prime movers for the one fifty-five howitzers had hard rubber tires. In short order those roads were just a muddy mire, and they had to cut trees and corduroy the roads, which was rather primitive but a good way of getting the units together. Not too long after, this battalion of the Eleventh Marines was divided into three. My first assignment was as a supply officer with the Third Battalion.

“Lieutenant Colonel James Keating from Philadelphia was designated battalion commander, and he called me over and said, ‘Russell, you’re going to be the supply guy. Go down to the quartermaster supply outfit, see where it is. They must have some kind of a list telling you what we rate [qualify for in the way of supplies].’ He said, ‘Start as soon as you can because we’re going to need stuff.’

“Fortuitously we got a supply sergeant who knew the business, so I depended heavily on him. God bless the noncoms, all of them. That’s one of the first things I learned, and it helped me through a lot. He was so good we decided to make him a warrant officer, so he became the supply officer. And I wanted to get into a firing battery, so I became the exec of the H Battery of the Third Battalion, Eleventh Marines.

“Things were accelerated once December 7 occurred. I was at Quantico visiting my fiancée, Eileen Herlihy, when Pearl Harbor was attacked. I’ll never forget her father. He was old Navy, with the Department of Yards and Docks. He supervised all the barracks building for the Marines. She had spent almost her whole life at Quantico. She told me, ‘Well, I’d like it very much if you made a career of the Marine Corps.’ As it turned out, we spent the next five or six years involved in it [the Marine Corps] with no flexibility [because of the war]. I liked the Marines. She didn’t have to make the decision for me.

“We got married on the twenty-seventh of December, 1941. We were going to get married in April, but we decided it would be good to do it now. Even though she was never officially in the corps, she was a great marine, the greatest asset I could have had. If I have had any success, she was a very significant part of it. We were married fifty-seven years. She died, unfortunately, six years ago from ovarian cancer.

“I was sitting in a hammock on her porch on the base at Quantico when her father came rushing out, saying, ‘Those goddamn Japs.’ He was a good old Irishman. He kept us posted, listening to the radio. Finally he came out and said all military personnel should report immediately back to their camps. I had ridden up with one of my friends stationed at New River. He had gone on to New York, and he came back shortly after and we went on back to New River. There were four officers in the H Battery. I was of course the junior one. One officer had to stay there for the Christmas holidays. That was me.

“I had the next section beginning on the twenty-seventh, so she came down with her mother and we were married in a church about forty miles from Jacksonville. Her father was sick and couldn’t make it. For a honeymoon we got on a bus for a thirty-hour ride to Rhode Island, where I introduced her to my parents. Then we zipped back to North Carolina.

“Our artillery unit had started with French seventy-fives, the seventy-five-millimeter field gun, and then we got seventy-five-millimeter pack howitzers. We got the word to move out in March. It took us a long time to get loaded. I was in charge of my part of the battery. We had the guns and the troops in about eight freight cars and one Pullman. Officers were in the Pullman, and the troops were in the rail cars, where they just nailed bunks together out of two-by-fours. It was miserable. We had our regular field stoves, and they just screwed those into these big old boxcars. We zigzagged back and forth. It took eleven days to get across the country. We had four pieces of artillery, the pack howitzers, all on flatcars. We’d stop at a siding so the cooks could prepare meals. There were no heads or anything like that. They had to use the bushes.

“We finally got to San Francisco, then left there in early May of ’42. The First Marine Division’s job was to defend New Zealand, so we landed in Wellington. The complexion of things changed drastically after the battle of the Coral Sea and the battle of Midway, and then they discovered the Japanese were building an airstrip on this unknown place, which was a key position to cut off the supply line from the States to Australia and New Zealand. The airstrip came to be known as Henderson Field, and the island was called Guadalcanal. It was in the Solomons. And everybody said, ‘Where the hell is that?’

“It had to be taken, so instead of going ashore and into camp in New Zealand, we unloaded. We didn’t have all these sophisticated amphibious shiploading techniques. We had one basic approach, and that was: What you want to get off first, put in last. Everything was in these paper cardboard cartons. It was rainy season, so we had to unload on the wharves. They got wet, and we lost an awful lot of stuff, but we got loaded up and took off, probably in July. If you can believe it, when we were leaving the States, we were issued five-gallon aluminum cans of hardtack from World War One.

“Nobody had any idea about Guadalcanal, no charts or anything. And our information was based on a sketch from the manager of a plantation that had been owned by the people who made Palmolive soap. There was no resistance. Carrier aircraft would come in and bomb, and we just sat there and waited, and then we got in the boats and had a successful landing, but it was strictly without opposition. The Japanese were away.

“I went in on the George Elliott, which was a transport. The second day the Japanese sent over a big flotilla of twin-engine bombers, and they were after the transports. My battery was attached to the Second Battalion, First Marines, H Battery. The transports had started unloading. Their holds were open, and apparently one of the planes got hit and crashed into the superstructure of the Elliott, killed all the people on the bridge. The flaming gasoline spilled into the open hatches, and the ship caught on fire, so I lost everything from the start.

“Fortunately we had the guns off and some of the rations and a good amount of the ammunition. They continued unloading all the other ships. The Elliott was the only one that was hit, and the second night was the battle of Savo Island, August 8–9, 1942. I don’t think it’s possible to describe the thunderous noise and the brightness of the light. It was about midnight, and of course we thought our Navy was really clobbering them. In the morning we had switched positions. We could fire out to the ocean or fire inland, depending on the need. We were watching along the ocean, and we could see sailors swimming or bodies floating, and a couple ships drifted down by there, superstructures all knocked over. This was my first combat.

“We learned fairly soon that we had lost four cruisers, The Quincy, the Historia, the Vincennes, and the Canberra, and fortuitously the Japanese didn’t follow through. They clobbered them and took off. They could have just wiped everything out. Next day the fleet commander, Admiral Ghormley, decided to husband what units he had, so he pulled everything out. Well, we weren’t unloaded completely, so we ended up very short of supplies.

“It was just about this time that I got to know Joe Foss. [Foss received the Medal of Honor for shooting down twenty-six enemy aircraft during the Guadalcanal campaign.] I got to know him because my battery was along this fighter strip, and those guys, aviators, you know, they don’t have much sense, and they didn’t have any place to protect themselves. So whenever the Japs came in to bomb, they’d come running over to my battery position, and I took care of them. So I knew Joe Foss, I knew him very well. I’m so sorry he passed away; he was a great guy.

“They tried to run supplies in, but they couldn’t until finally they did begin to get a few in at night. They had some of these old World War One destroyers they had taken the stacks off. They’d get in about dusk and unload and get out of there before dawn. And even they got hit. We were subject to air bombardment every day, oftentimes several times a day. It was not unusual for a Japanese naval vessel to stand offshore and just lob shells in. One shell landed very close to my position, and a hunk of shrapnel hit me. I saved one piece. It got me in the arm and the side. By that time we all had malaria too, you know. Malaria was endemic. The shrapnel didn’t stop me. It wasn’t that serious, and you couldn’t evacuate casualties anyway. I got a Purple Heart out of it. I got one on Iwo Jima too. I was promoted to captain a year and half after being commissioned and served as battery commander for quite a while on Guadalcanal.

“Finally the First Marine Division units were being relieved by Second Marine Division units, and then some Army elements came in. I think the Army took over responsibility probably in March or April of ’43. We went to Brisbane, then Sydney and finally Melbourne. We didn’t suffer the high rate of casualties we were to have at Iwo. I’d say about eighty percent of the battery was intact. From Melbourne we moved out to an old Australian army camp, and I got sent back to the States because of my malaria.

“They were just starting the First Marine Corps Command and Staff School at Quantico, and of course my wife was there. I was assigned, and about that time I got promoted to major. I was there six or eight weeks and then got ordered to an advanced officers’ course at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for ten weeks. My wife was able to accompany me; this was still ’43. When I got back to Camp Lejeune, they were just beginning to form the Fifth Marine Division. The artillery for the division was the Thirteenth Marines, and I was ordered to the Third Battalion. The rest of the Fifth Division was being formed at Camp Pendleton in California, so we got the Third Battalion fairly well formed and then moved to Pendleton in the late summer of ’44.”

Russell was the battalion executive officer, but there was a great deal of rotation going on as more senior officers came back from the field. He was pushed out of the exec job to operations officer, somebody else came in, and he was pushed out of that.

“They were talking about sending me back out. I hated like heck to have to leave my wife when we were finally getting acquainted after three or four years of marriage” [so he transferred to an infantry battalion and became the exec there]. So I became an oh-eight/oh-three, artillery-infantry.

“It wasn’t easy because the Marine Corps had these raider and paratroop outfits, and I think, wisely, they decided to disband them. A marine is a marine. They didn’t need all this fancy raider stuff. But all those people, these prima donnas, were thrown into this regiment, and they were horrified to have an artilleryman in the outfit. I had to really work and work and work to gain their respect. Any time there was a hike I was always leading it. They had a lot of swimming pools, for amphibious training. They had a platform twenty or thirty feet high. You’d have to climb up that with your full pack on and either be pushed off or jump off into this pool. And of course the pool was crystal clear, and it looked like you were up about four hundred feet.

“When it came time, I was the one designated to take the battalion up. And you know, all the troops are looking and wondering what the heck’s going on, so who has to go up the damn ladder? First one was me. Oh, I tell you when I looked down there, I thought there were a lot of places I’d rather have been. But I said, ‘I gotta go, and I’ll show these so-and-sos.’ So I went. Full pack, combat boots, everything. It gradually got to the point where I had the confidence of the troops and the company commanders, so everyone was comfortable with me by the time we got the word for Iwo Jima.

“We made the landing on Red Beach One. I landed in the third wave, which was the first of the LCVPs [landing craft, vehicle, personnel] fourteen to twenty minutes after the first waves landed at eight-twenty. The first two waves were amtracs. Our mission was to cut across and go up the other side.

“When I got out, I had my jeep in this boat, and when we got out, I kept yelling to the troops, ‘Get off the beach! Get off the beach! Get up on the high ground!’ And of course they were trying to climb up that soft volcanic sand. It was extremely difficult. You’d go up, and you’d go sliding back, and already there were a lot of casualties. There was firing on the beach, not the heavy volume that came later, but there was firing.

“I got the troops out, and the driver of the jeep got it across the ramp, and as soon as the front wheels hit the soil, it started to spin. He couldn’t get it any farther than that. We were trying to get up the hill, and when I looked back he had got out of the jeep. One of the kids had been hit, and I was seeing how bad he was hurt. When I looked around, the driver had gotten out, and he must have got hit; there was this enfilade fire coming up the beach, and it looked as though he was just broken in half. He must have got it in the midriff. One of the sailors on the ramp just reached over and dragged him in. The coxswain then took the LCVP and jiggled it back and forth back and forth to get rid of the jeep and I just remember seeing my jeep just gradually slipping down into the sand. It became part of that pileup of debris all along the beach.

“We were under fire from all directions, heavy fire from just all over. I don’t remember being appalled. I was kind of dismayed, I guess you could say, but I was more interested in getting the troops up and on the higher ground where they wouldn’t be so vulnerable. I did not know Fred Haynes then [see Chapter 4]. I may have known him as officer in the Twenty-eighth Regiment. My regiment was the Twenty-seventh. My job as executive officer was to get the troops in and coordinate the command post.

“Iwo Jima was an action of constant, constant fire all the way through, twenty-four hours a day even to the thirty-sixth day. It was just constant. Guadalcanal was spasmodic; there were times you could just take it easy. Korea you were in trenches. But at Iwo there was artillery, mortars, machine guns, rifles, everything, and they would pop up from places you least expected. Of course they don’t mention it much, but we thought this was gonna be a piece of cake. We were going in there for ninety-six hours just to kind of, you know, wipe up what was left, and go on and support the Okinawa operation.

“The fact that they had all these troops in tunnels came as a big surprise. When I went back the first time, I was almost confused. There was something different. All of a sudden I realized that when we landed, there wasn’t a blade of grass on that thing. They had pulverized it. I mean everything. It was just bare soil, and it was hard to imagine that anybody could survive in that, but they were so far down. Last time I went out I was amazed that the caves held up so well even after all these years, because of the consistency of the rock. They just chipped away and chipped away. They didn’t need anything to support it.

“I recall having two code talkers with my unit. My experience with them went back to our training base in the Hawaiian Islands. We worked for quite a while with them when they first joined us. I had one, and the battalion CO had one. He might send a message to me saying, ‘I got a call from the Baker Company or Easy. They need some ammunition. Get it for them.’ He’d write it out in longhand, and the code talker would go off and transpose it. Then he’d get on the radio and send it and nod to the battalion CO that it was on the way. Then I’d see that Navajo on my end pick up his phone and start writing. Then he’d go off to the side, transpose it into English, and hand me the thing. They were very well organized. They went through the routine and knew exactly what to do.

“But the first five days on Iwo were so heavy I really don’t recall using them too much. That action was so concentrated. It was just day and night. You hear people say, ‘Well, when did you sleep?’ You didn’t sleep; you just got by. It rained the first couple days. You’d stick the poncho over your head, and after a while you’d get soaking wet, but you just took it. That’s the way it was.

“For meals, you grabbed something when you could. We did have some canned C rations. It was interesting, you could dig down six or eight inches, put the can in, and in a half hour it would be cooked. If you dug a foxhole, you had to wait for it to cool off before you could get in it. It was an amazing phenomenon.

“I was taking care of all the details that came up, making sure there was ammunition or rations or that casualties were taken care off, radios, runners, telephones. Hell, the ground looked like spaghetti, with telephone wire going everywhere. My battalion CO was a major named John Antonelli. He got through OK. About the sixth or seventh day we had been pulled off the line. Of our original twelve hundred, we were down to around four hundred men. By this time Suribachi had been taken, so they could bring in replacements. So we were pulled off the line and brought down, and we got our replacements, and we were trying to filter them in where we needed them. We got a good meal for the first time, had a chance to bathe a little bit.

“Next morning the regimental CO called the battalion commanding officer so he could show him where the battalion would be moved back up to the front. The battalion CO went up in his jeep, and I led the troops up. I was out in front of them, and I had them spread out with a good interval between each one, two rows going up this full road. I came up on the top of the hill, and there was a cut in the road, not quite as wide as this room, and when I got to the top, I could see all the way to the end of the island, and just as I got there, a shell hit the side of the hill.

“It threw shrapnel all over, and I got hit in the face. It barely missed my eye. I landed in the ditch on the side of the road. I was groggy, but I told the headquarters company commander to take the troops down around the back of the hill and then notify the battalion CO. Next thing you know I was being driven down to the beach by the regimental CO. I was sitting in the front seat with blood all over me, and the battalion CO was holding me so I wouldn’t fall over.

“We used to get these two-ounce bottles of Lejeune medicinal brandy, and they were giving that to me, plus I think the regimental CO had a bottle, so by the time I got to the beach I didn’t know much of anything. Anyway, they claim I insisted that I not be evacuated. I remember vaguely going through the next few days with a big patch on my face. Three or four days after that, halfway through the operation, well into March, Antonelli, the battalion CO, got hit, and he was evacuated. That’s when they talk about me being one of the last remaining battalion commanders because Antonelli died four or five years ago. At any rate, I took over the battalion and brought it all the way through for the rest of the campaign, right to the end.

“We always tried to dig in for the command post. We tried to be as close to the front as we could, and usually we were one hill behind the front lines. Take the case of First Lieutenant Jack Lummus, who was to receive the Medal of Honor for all the stuff he did on March 8. His action was up front of us, on sort of a mound, you might say, and the CP was behind it. I remember when they brought him back. He had stepped on a mine, and both of his legs were blown off. They weren’t bleeding.

“He was on a stretcher, and I lit a cigarette and held it for him. Jack had been an All-American at Baylor and was an end for the New York Giants. He talked reasonably cogent, and of course I was shocked that he wasn’t bleeding. I learned later that shock just clamps things off. Anyway, he said, ‘Well, I guess the Giants have lost a good end.’ And I said, ‘Jack, the Marine Corps has lost one hell of a good officer.’ They took him in the jeep down to the clearance station. I talked to a doctor down there afterward, and he said he didn’t have a chance. He said what you didn’t see was the fact that his stomach was all ripped open. He said he could reach in and pull a handful of dirt out of it.

“We went through the whole thing on the front lines all the time. On the morning of the fifth day we had swung up to the north, and we were having a hell of a time. Our two code talkers got clobbered that fifth day, and one of them was in a shell hole for two days before we could get to him, the action was so intense.

“We were facing away in a kind of crevice, and one of the kids yelled, ‘Look!’ He pointed up, and there on the top of Mount Suribachi we could see this small group of men and Old Glory. It was very emotional. You can’t imagine how I felt. There was an old gunnery sergeant standing near me. He was about six feet two and had been in the Marines for I don’t know how many years, the Old Corps, you know?

“This guy had the most colorfully profane vocabulary I’ve ever heard. How he could conjure up some of these things was just amazing. He never showed any emotion or anything else, and on the fifth day we were coated with that black grime. We barely had enough water to drink, let alone to wash. When the flag went up, I couldn’t say anything. I had a lump in my throat, and I don’t know if I had any tears, but I looked at this guy who I never thought had an ounce of emotion in his body, and he looked at me and you could see tears coming down through this grime on his face, and he said—and I’ll never forget it—he said, ‘God, that’s the most beautiful sight I have ever seen.’

“I’ve said this in Flag Day speeches and stuff that up to that point, we weren’t sure whether we were going to succeed or not. But from that moment on, when the flag went up, we knew we were. It didn’t get any easier, but we knew we were going to win. We were reminded of what we were there for. I don’t know which flag it was, but it was in the morning. We just kept going. We were just relieved that they had taken it.

“Iwo was a place where you had to go in and dig the enemy out, where you had to use flamethrowers and satchel charges. It wasn’t just huge barrages of fire. For example, we were in an area where the rocky formations were such that every time our troops would try to maneuver, the Japs could come out of these caves and fire on them. We needed some kind of heavy fire, and there was no way we could get a tank in there.

“Being an old artilleryman, I suggested we get a pack howitzer, because it breaks down into seven or eight pieces. It was originally designed to be carried by donkeys or mules. It was easily portable. This weapon was designed primarily as mountain artillery that could be broken down and taken ashore in six loads from a boat. It became an important support weapon of the Marine Corps at every major landing in the Pacific. It was crewed by five men and could throw a sixteen-pound shell almost ten thousand yards. So I recommended we get one up there at night, set it up, and start using it during the daytime.

“But the regimental executive officer of the artillery said, ‘That’s damn foolishness; it’d never work.’ But apparently General Rockey, the division commander, said in no uncertain words, ‘If they want it, get it and give it to them.’ So they brought it up, just this little group with one gun. They put up the gun at night, camouflaged and put rocks around to protect it. We used it, and we moved right through after that. But again it was that individual action, individual initiative.

“We kept losing men after I took over the battalion, and we got a few more replacements. But by the end of the operation there were so few left in the whole regiment that they consolidated the First, Second, and Third into a sort of temporary battalion. There was just one lieutenant colonel left, a guy named Don Robertson. He took over.

“The most vivid memory I would mention out of all that time was the flies and the smell of the dead. That’s something they don’t mention in documentaries, but boy, when you have that many bodies all over the place, it’s sometimes days and days before they can bring them out. The flies and the stench were pretty bad.

“I carried a forty-five, but I never fired it. Three or four days before the end of the operation I had the remnants of my companies together, and we were dug in. I was in a foxhole myself, and I had a phone from each one of the companies. They were having trouble, and we needed some heavy fire. I had requested a tank. When it came up, I went around to the side away from where the Japanese were, so I had some shelter. I got the phone from the side of the tank, and I told them inside exactly what fire we needed and where. I vividly remember that when the sixty-millimeter small-caliber mortar shells would explode, they gave off that yellow picric acid kind of smell. When they acknowledged my message, I ran like heck back and jumped into my hole. Well, while I was gone, a shell had landed in there and chewed up all three phones and everything else. We always have an expression: If your name is on it, no matter what happens, you’re going to get it. I guess mine wasn’t on it. To this day I kinda sweat a little bit when I think about that one, right up almost to the end. They didn’t give up. They fought all the way. Talk about a hunk of hell, it really was.

“I think the battle of Iwo Jima is one of the truly great landmarks in the overall history of the Marine Corps. It was an achievement tremendous in its significance because of the way we were able to handle it, win it.

“The performance of the troops became a defining statement for what marines can accomplish because at times it seemed hopeless. We were still able to keep going, day after day, with an unbelievable number of casualties. It was unsurpassed. We never had anything like it before. The troops, those marines proved that no matter what, we would succeed.

“After Iwo, and as soon as we got back to the base camp at Hilo in the Hawaiian Islands, we immediately started getting ready for Operation Olympic, to land on Kyushu. We trained, got replacements, then the two atomic bombs were dropped, and the Japanese sued for the armistice.

“They took the First Battalion, Twenty-seventh Marines, and the First Battalion, Twenty-sixth Marines, to make a preliminary landing during the occupation. We didn’t know what to expect from the Japanese. They had been treacherous, mistreated our prisoners of war, and so we went in ready to fight. But they were the most docile, cooperative people you could ask for. Honor is so important to them, and the emperor said, ‘Do what you’re told, and cooperate.’ I never had one bit of trouble with them.

“So I spent almost a year in the occupation, and I got a couple key assignments. One was to accept the surrender of the Tsushima Islands under Lieutenant General Bukei Nagasi. The Tsushimas were the pair of islands in the Sea of Japan with Korea on one side and Kyushu on the other. I got some pictures of the guns we had to blow up, fourteen-inch naval guns.

“I went in with my battalion on LSTs. I had a group of twelve interpreters from the Home Ministry. General Nagasi was from the old warrior class, very distinguished, a very proud, very pleasant guy. He had eight thousand troops, and I had a little over a thousand, and his were crack troops, and I wanted to get them the hell out of there. I commandeered every damn fishing boat, everything I could find, and put them aboard and sent them back to the mainland.

“I’m still just a major in my mid-twenties, and this lieutenant general kept saying, ‘Well, when can we make arrangements to have a surrender?’ He kept saying, ‘Well, when is your general coming?’ And I had to tell this poor old—you know honor would dictate somebody of the same rank would accept the surrender, and here he has to surrender to this punky major. By virtue of that, I got to know the Japanese people and everything, so I could see their side. There were some things I had come to understand about them where they felt justified in a way.

“Japan was a small country, very short of minerals, and all the metals of the world were right there in their backyard, all controlled by countries half a world away. They got it through colonial efforts; why can’t we do the same thing? I think they felt we’d back down if they showed any force. They thought the United States was a bunch of pussycats, wouldn’t be willing to fight. Of course Kuribayashi and I think Yamamoto knew better, but nobody listened to them.”

Gerry Russell retired from the Marines in 1968 as a full colonel following service in World War II and Korea, then as a regimental commander after that. He commanded the ground transport in Guantánamo during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. He and his wife had two daughters, Eileen and Maureen. He spent his postmilitary years at Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania. He has been the chief finish judge of the Millrose Games for many years. He never made it to Harvard.