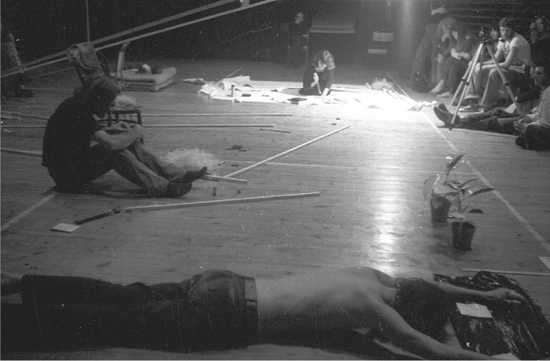

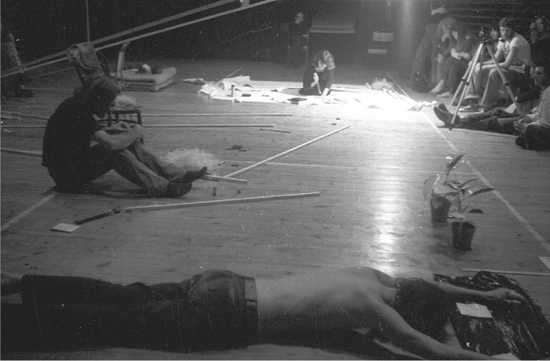

Courtesy: Richard Demarco Archive.

The idea of an internationalist, critical, and progressive art movement became increasingly popular in the field of the international 68ers movement. It was often the artists themselves who wanted to overcome the narrow national or regional frontiers with their works, in order to take part in global communication. Participating in international discourse presented a great challenge, above all to those artists for whom it was made very difficult, because of the political situation in their countries, to act outside the established aesthetic norms imposed on them from above. Especially in the socialist-governed countries of Eastern Europe, but also in those governed by dictators, the emancipation movements of the late 1960s, and along with them the entire transformation of the field of experimental and avant-garde art, were often branded and marginalised as subversive and destructive to the state.1

After leaving the Kominform2 on June 28, 1948 Yugoslavia turned into the “other” socialist state.3 For Western countries it became the embodiment of socialism with a human face, favourite child and example for many, above all for progressive left-wing intellectuals in Frankfurt School circles. Among real-socialist states of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, Yugoslavia represented an ideal of liberty, a country with freedom to travel and with freedom of expression.

Oriented culturally toward Western Europe and the US, and politically toward the so-called Third World, the country under Josip Broz Tito’s rule took on the role of a buffer state between the Eastern and the Western blocs. This constellation was from 1961 on manifested in the founding of the movement of “non-aligned countries”, which – with all the associated contradictions and difficulties – would characterise political and cultural understanding until the fall of the Yugoslav political union in the 1990s.

The dissatisfaction with which the post-war generation regarded the prevailing conditions, as well as the search for a New Sensibility (Marcuse 1969), also dominated the cultural scene in Tito’s Yugoslavia during these years. A vibrant and urban avant-garde scene developed in the cities of Ljubljana,4 Zagreb,5 Split,6 Belgrade,7 Subotica,8 and Novi Sad,9 which strove for a new perception of art as a social practice to further the destruction of predominant aesthetic and ideological norms. Between about 1966 and 1980,10 Yugoslav artists and intellectuals were linked up with their European international contemporaries. Information from cultural centres such as New York or London reached Belgrade almost immediately; artists took part in international exhibitions and conferences. In short: Yugoslav neo-avant-garde and conceptual art were an international phenomenon.11

There were several levels on which the international networking of the Yugoslav post-war avant-garde took place, both institutional (supported by public authorities), and private (self-organised collaborations that took place outside institutions). Apart from the organisation of exhibitions with international participation, there was also a vigorous exchange of ideas, as is reflected in the dissemination of gallery talks, correspondence, and theoretical papers in magazines such as Index, Polja (Field), Student, or WOW, which were often published by the artists themselves.

The first part of this text outlines the key role of the artist and organizer of the Edinburgh Festival, Richard Demarco, as a mediator. Working together with Yugoslav authorities, he put on two group representations of Yugoslav performance and conceptual art in the framework of the Edinburgh Festival. These semi-institutional collaborations can be compared to the artistic interventions of the Bosch+Bosch Group, who, through actions and performance works, broached asymmetries between international participation and local marginalisation. Both examples are, directly or indirectly, connected with the student cultural centres of Belgrade (from 1971), Zagreb (from 1957), and Novi Sad (from 1954), representing alternative cultural spaces at the margins of official culture, where experimental and progressive artistic practices – such as performance, body art, and conceptual art – could develop under “controlled conditions”. I will apply the complex, sometimes paradoxical notion of the “second public sphere” to these venues, as they acted from a peripheral position, reaching a limited audience and promoting an overtly antagonistic cultural model. They were, nonetheless, financed by public funds and had an official status within the (first) cultural sphere. The development of new artistic practices and experiments in Yugoslavia would be unthinkable without the existence of these centres. The reason for the relatively tolerant position of Yugoslav cultural policy in these semi-official venues was clearly to present the image of a tolerant and open cultural nation to the rest of the world, yet to follow cultural politics internally that were in line with the political reflections of the party. This ambiguous and to some extent paradoxical stance is traceable in the nature of the collaboration with Demarco and the Edinburgh Festival, where the most progressive and radical artistic experiments of the time were not only presented to an international audience, but also supported with public funding, although in Yugoslavia itself they were kept at the very margin of the cultural sphere and were hardly visible to a broader audience.

The notion of a second public sphere in the specific Yugoslav context was different from other socialist countries, where the avant-garde of the time was often overtly banned, forbidden and forced to withdraw into private or underground spaces. The student cultural centres could best be described as “reservations” at the margins of official culture, as Miško Šuvaković describes them:

The Student Cultural Centre was for many years a place of investigation for the experimental, polymediatic, interdisciplinary and the conceptual. At the same time it was a place of the new free art, and a reserve, in which the party leaders of socialist Yugoslavia demonstrated their openness and readiness to adapt cultural politics to the new and emancipated processes of the international art scene.

(Šuvaković 2009, p. 382)

In the 1960s and 1970s Yugoslavia was considered to be a relatively liberal and free country, where there was freedom to travel and a particular tolerance toward innovations and modern artistic tendencies (Lampe 2000, p. 267). Under the banner “New Art Practice”, which refers to multiple artistic forms of expression and movements of non-representational and post-object art, including forms of neo-Dada, Fluxus, happening, performance, conceptual art, land art, and arte povera, among others. All of these could be found in Yugoslav art during this period, and all characterised the international art scene as well.

The common denominator of these heterogeneous phenomena within a Yugoslav context lies in a critical analysis of the existing practices of art and artforms in general. In contrast to the institutional critique of West European and US-American conceptual artists, who primarily wanted to withdraw from the increasing capitalisation of the entire art field, and who recognised an apology for the capitalist system and its institutions in the object-fixation of modern art, the institutional critique of East and Southeast European conceptual and performance art is somewhat different. Apart from art institutions, the ubiquity of the institution is a problem per se. Since all state institutions pursued the same aim – the protection and propagation of the socialist idea – critique was not limited to state institutions. It represented a comprehensive rejection of the ruling powers’ influences on the scope and content of art. The strategy of dematerialising the art object may be interpreted as an internal stance of resistance. Free areas of creativity, not accessible in the external world, accumulated, either partly or completely, in their own consciousness, and were manifested in a presentable, mental, and critical stance. This laid the foundations for their own existence as well as for ethically motivated alternatives. Consequently, neither exhibitions nor presentations of this art were overburdened with serious material or logistical problems. Their informative character allowed for fast-moving organisation, performative demonstration, and bypassing of the official system of communicating and presenting.

Critiques of the ideological order of Yugoslav social and cultural models, could not, however, be directly formulated in the context of the official (first) public sphere. Rather such critique was channelled into a second area of public domain (primarily the cultural centres), the outside influence of which was limited and marginal. When, on the one hand, Marina Abramović included an insignia of the state, the five-pointed red star, in one of her early performances (Rhythm 5) at the April meeting of the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade in 1974, this could be seen as the expression of an individual and subjective act, and not as an attack on the state as such – and so it wasn’t sanctioned as a subversive or critical act. When, on the other hand, Slavko Bogdanović, member of the Novi Sad-based group KOD, attacked the system openly and directly in his poem “Youth Tribune Underground Song” (“Underground Pesma Tribina Mladih”), the state reacted with drastic sanctions and sentenced him to a prison for several months. The artist had refused to act within the framework of the second public sphere allotted to him, with its limited possibilities for participation and public effect, but rather had attempted to approach the primary public sphere. This represented an intolerable affront and provocation.12

Young experimental artists, who often formed groups within the milieu of the student cultural scene, operated on equal terms with (West European and US-American) representatives of this renewal movement and were in close contact with artists, theoreticians, and curators from different countries. It is important to emphasise the fact that the international exchange was not one-sided but mutual, as is attested by a range of collective exhibitions, initiatives and collaborations.13

The internationalism of the Yugoslav avant-garde was determined by formal and institutional co-operations, private collaborations, private friendships and semi-official networks. One of the prerequisites for this internationalism lies partly in the fact that there were almost no travel restrictions or limitations for the Yugoslav passport, neither to Western nor to Eastern foreign countries.

According to Ješa Denegri, who as curator of the Belgrade Museum of Contemporary Art and convinced supporter of the new art practice played a central role in transmitting its contents both inside and outside the country: “For almost the entire second half of the 20th century, roughly from 1950 to 1990, i.e. until the disintegration of the ‘second Yugoslavia’, Serbian art can and must be considered within the context of the Western, rather than the Eastern European art scene, because it is with the former that it had numerous immediate ties” (2004, n.p.).

The examples of international collaboration and international exchange this text is dealing with are primarily between West European and Yugoslav protagonists and institutions. Without going into the issue of the general dominance of the “Western” art world (as opposed to, say, Afro-Asian, Australian, South-American), the alliance of Yugoslav artists with the West did not mean that artists had not recognised this issue.14 The orientation toward the West was understood as a deliberate distancing from the cultural sphere of the Soviet Russia–dominated community of states, with which they shared, with rare exceptions, few points of reference.15

The most important series of events, organized at the SKC from 1972 until 1977, featuring crucial conceptual artists of the time and connecting Yugoslav conceptual artists to contemporary international events, are the so-called April Meetings of Expanded Media (Aprilski susret – festival proširenih medija). These events were characterized by a strong interdisciplinary artistic program, including workshops, performances, lectures, and exhibitions with local and international participants. The April Meetings suggested a general atmosphere of freedom and emancipation, with its distinctly cosmopolitan behaviour and networking of artists and critics. They are one of the most vivid examples of the Yugoslav avant-garde scene’s international character, making Belgrade and the SKC one of the hotspots on the international art map.

The best-remembered event took place in 1974, when German artist Joseph Beuys, critic Barbara Reise, and Italian art critic and curator Achille Bonito Oliva were participating. The visit from Beuys, who the participants had met in Edinburgh the previous year at the exhibition organised by Richard Demarco, and whom they had invited to Belgrade, is a key event in the history of Yugoslav post-war avant-gardes.

In his lecture-performance on April 19, 1974 with the title Expanded Media or New Art, Beuys introduced central elements of his evolutionary-revolutionary theory, according to which genuine social transformation can only derive from the artistic field’s extension into social practice (1974, p. 48). The content of Beuys’ lecture and the discussion that followed was not recorded in writing, making a retrospective analysis difficult. According to Denegri’s (2003, p. 64) firsthand account, Beuys gave the short version of his signature talk, which was grounded in sociological, philosophical, and artistic questions. He drew symbols on a blackboard to help explain his thesis, identifying art and creativity as the means by which human existence reaches maximum individualization in relation to surrounding social and political structures. Insisting on the interconnectedness of man and art, he emphasized the importance of creating dialogue through art. The fact of his presence in Belgrade, where among other activities he saw Marina Abramović’s Rhythm 5 and witnessed its later declaration to a key happening in the history of the Yugoslav neo-avant-garde, serves as a proof that the local art was perceived as a global phenomenon. This enthusiasm was only slightly dampened by the critical remarks of Achille Bonito Oliva, who, at the same event, had labelled the SKC as a reservation cut off from social reality: “You are in a reservation which is completely closed and isolated from the culture in which it takes place, and the socialist bureaucracy shows by using you that it appreciates international art, but, actually, keeping its moderate modernist or social modernist practice away from you” (Šuvaković 2008, p. 53). His words, which are a poignant definition of the functioning of the second public sphere, provoked some degree of disappointment and incomprehension, although the organisers agreed that in all of Yugoslavia there was no comparable place in which the latest local artistic tendencies could meet international events on an equal footing.

A remarkable case of Yugoslav New Art getting in touch with the international art world was through a cooperation with the Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh. It was founded in 1966 by Italo-British Richard Demarco and was one of the first Western European galleries to foment intensive contact with the art scene of Eastern Europe. The first exhibition dedicated to Yugoslav performance art took place there in 1973, which is one of the first examples of its international presence.

Demarco’s interest and commitment was driven by the need to show an alternative to the Western-dominated perspective in Europe, and to offer East European artists a platform to present their work:

However, I saw the danger of European art all too easily defined by the Western European artists who dominated the Venice Biennale and the Documenta exhibitions of the sixties, therefore I endeavoured also to extend at the same time the Gallery’s dialogue with Eastern Europe with major festival exhibitions of Romanian and Polish Art in 1971 and 1972… . Then Edinburgh could have provided what the Documenta had failed to do, and allowed Eastern European artists to compare their work with what they had come to respect as the New World complement to their own.

(1976, p. 1)

Between December 4 and 12, 1972, Demarco undertook a nine-day journey through five Yugoslav states, with the aim of making contacts in the contemporary art scene and to prepare a presentation of them in Edinburgh.

An interesting fact in this context is that the trip was of a highly official character and had not been brought about in a clandestine manner, in order to meet “regime-critical” artists from the second public sphere. From a ten-page report (ibid., 1972b) on this journey it follows that his aim was not only to meet representatives of the new artistic practices – the young avant-garde – but also established artists of the older generation, who felt committed to a formal aesthetic, corresponding to the official aesthetic programme of “socialist aestheticism.”16 The apparently eclectic group of artists visited by Demarco shows the ambivalence between local tolerance and channelling of New Art at a national level and its official public support at presentations abroad, a recurrent element, and a consequence of the cultural-political orientation of Yugoslavia as country “in between”. Despite intensive exchanges and several trips inland, Demarco saw the result of this journey as only the beginning of an intensive phase of collaboration. He noted: “I realized I had merely scratched the surface of the art world in Yugoslavia, though I had been on four all-night journeys by train, one jet flight, and I had visited five cities in nine days, and had been in twenty studios and met fifty-one artists, and twenty-five art critics and gallery directors” (Demarco 1972b, p. 12).

Courtesy: Richard Demarco Archive.

Demarco’s journey through Yugoslavia finally resulted in one of the first collaborative presentations of Yugoslav conceptual and performance artists at the Edinburgh Festival in 1973. In a letter to Oto Denes (Demarco 1972a), deputy director of the Yugoslav Federal Institute for International Collaborations in Science, Culture Education, and Technology, from December 26, 1972, Demarco passed on a list of those artists whom he would like to invite to the Edinburgh Festival in 1973. Among these were important protagonists of conceptual and performance art (Abramović, Todosijević, Urkom, Vlahović, Damnjanoivć-Damnjan), but also “traditional” artists of the older generation such as Olga Jevrić, Oto Logo, Radomir Reljić, and more, in all about seventy artists from all the Yugoslav republics.

Finally, Demarco organised 8 Yugoslav Artists in August 1973, including a group of six artists17 from Belgrade (Abramović, Paripović, Urkom, Todosijević, Popović), as well as Nušo and Srećo Dragan from Ljubljana and Radomir Damnjanović Damnjan.

As part of the Festival Marina Abramović carried out her first performance, Rhythm 10, which, in an exemplary manner, serves as a basis for her later works and contains the central motif of her oeuvre, which is the concern with the physical limits of the body, pain and memory. In Rhythm 10 ten knives of varying sizes and a tape recorder are used. Abramović, as in the “five finger fillet” game, moves the knives progressively faster over her hand. As soon as she injures herself, she picks up another knife and starts again. An acoustic record is made with the tape recorder and the moment of the injury is thus captured. The tape registers each occasion when Abramović gets injured. After all the knives have been used, the recording is played and the artist attempts to follow the prescribed rhythm.

With Rhythm 10 Abramović makes the definitive turn to body art and performance art, after prior experimentation with different artistic forms of expression (concrete poetry, installations, photographic interventions). Abramović’s early performance works do not follow any complex theoretical predispositions. They are, on the contrary, expressions of a direct and immediate existentialism which is concerned with questions of physicality, pain and extending boundaries, and in the last analysis naked life itself. In later investigations, these works were often imbued with symbolic meaning, an implicit political and activist background was ascribed to them, even mythological and feminist layers of meaning were found in them. While it is doubtless legitimate to ascribe symbolic content to some of these works, especially those from the Rhythm series (10, 5, 2, 4, 0), they are first and foremost radical performance experiments, which circumnavigate the complex relationship of artist–body–public realm and which sought to stretch boundaries along this axis. The repeated use of communist state symbols (such as the five-pointed star, partisan’s cap, uniform, etc.) are not to be regarded as critical remarks on a particular social order as such, but rather as deeply personal fragments of memory which have left traces in the artist’s biography (Ward 2010). The fascination with discovering heroic acts of resistance against supposedly repressive state totalitarianism in these works often seems to derive from a generalised view of all the art produced behind (or away from) the Iron Curtain. It rarely holds up to a detailed and (moreover) contextual reading of these events. It neglects, as Šuvaković (2008) puts it, “the very delicate, careful, bureaucratically well performed centering” of the Yugoslav cultural model.

Following 8 Yugoslav Artists Demarco worked on the realisation of a much bigger show, which was intended to include many of the artists who had appeared on the 1972 list (Demarco 1972b). After several trips to Yugoslavia, and others to the Croatian Motovun,18 in September and October 1975, together with Zagreb City Art Gallery, Aspect ’75 opened in Edinburgh, a large-scale exhibition in which the work of forty-nine contemporary Yugoslav artists of different genres and schools of thought were presented.19 According to curator Jon Blackwood, “Aspect ’75, in every sense, gave as full a picture as was then possible of art practice in Yugoslavia, from Croatian naïve painting and ‘socialist aestheticism’ through to performance and video” (2010, p. 5). On the cover of the catalogue there was a representation of a Yugoslav passport with the pun “Passepart”, a reference to the fact that in those years it was possible to travel practically anywhere in the world with a Yugoslav passport, as mentioned above. Aspect ’75 is an impressive example of the international presence of Yugoslav art in the 1970s and furthermore a highly official and paradigmatic realisation of the cultural-political orientation of the country, whereby the juxtaposition of the different artistic positions bears witness, just as much as the numerical balance from each of the eight Yugoslav republics. The curatorial concept, however, presenting radical performance and conceptual art alongside naïve painting and historical motifs, seems in this case to follow a kind of exoticization which does not consider the associated implications, the different creational contexts and political implications. The exhibition, with the subtitle Contemporary Yugoslav Art, showed works from artists of the most varied artistic languages. The spectrum extended from naive painting; extensive draperies and archaic woodcuts; to the photo-documentations of Marina Abramović’s Performance Rhythm 2 (1974); Braco Dimitrijević’s Casual Passers-by series, in which he set up large scale portraits of unknown, randomly selected people in public squares; or Raša Todosijevićs Edinburgh Statements, a pamphlet-like text, to be read as a totalised institutional critique in which he listed all those who would financially benefit in the art world. The setting of the exhibition was aimed at equal rights for all artistic forms and expressions. It was thus clearly aimed at showing the multiplicity and openness within contemporary Yugoslav art, on which there were no limitations or sanctions (as long as the artists restrained their sphere of activity to the alternative secondary spaces created for them). The evident eclecticism of Aspect ’75 may be regarded as a representative example of Yugoslavian foreign cultural politics, with all its contradictions and ambivalences. These are best seen in the following examples by the Bosch+Bosch Group, an artist’s collective active in the most northern part of Serbia, literally positioned at the (geographical and cultural) margins of the country.

The ambivalences and difficulties accompanying the “connection with the world” (Denegri 1977), far from the successful events within the framework of student cultural centres, are shown in the works of the Bosch+Bosch group, one of the first art collectives of Yugoslav New Art, founded in 1969.

The Bosch+Bosch group demonstrates well the contradictory nature of the cultural politics of the country, located between tradition and modernity, but also the self-positioning of the new avant-garde in this context. On the one hand characterised by the need to position itself in an international, even global artistic movement, this demand was, on the other hand, an ongoing challenge. Bosch+Bosch was acting from a marginal position in two respects: politically, from the perspective of the state that defined itself as “somewhat in-between”, and artistically, because the entire experimental counter-culture was regarded as fringe – a peripheral phenomenon constantly under pressure to demonstrate its legitimacy. This twofold marginalisation led the artists – above all, the two central figures of the group, Slavko Matković and Bálint Szombathy – to make this unsatisfactory position the object of their artistic investigations. The Bosch+Bosch group is therefore a paradigmatic example for the ambiguities and constant struggles that artists acting within the second public sphere were exposed to.

The photo series Bauhaus from Szombathy’s photo-performance20 of 1972 reflects the ambivalences of the experimental and event-based art scene in the context of the second Yugoslavia in a very convincing way. In the work, a signboard with the text “Bauhaus” is popping up in different places in an obviously desolate flat in Novi Sad (Szombathy‘s own) being photographed – sometimes with Szombathy in the picture, sometimes without. The flat is declared as Bauhaus by the artist. The contextual shift in this subtle intervention occurs on both a temporal and a spatial level – and receives its meaning from the discrepancy of interaction. In the action of transferring the ideals of Bauhaus, the symbol of international post war modernism, into the context of real socialism. They again are addressed in an absurd-existential meaning and deliver a statement on the significance of the avant-garde in cumbersome technocratic socialism, which liked to see itself as progressive, modern and forward-looking – just as the Bauhaus-School had – but was in practice, atavistic, anti-modern and overly bureaucratic. In other words, “Szombathy confronted the ideals of modernism as the culture of progress with the quotidian environment of the great majority of members of everyday socialist reality” (Šuvaković 2003, p. 119).

While Szombathy’s conceptually-motivated performance-action works could be characterised as semiotic interventions, with which he often contradicts the meaning of established visual signs to conditions in their surroundings, or rather which were contextual displacements of these symbols, the works of Matković have an existential dimension and expose the dilemma of an artistic existence trying to defy the adversities of everyday life in late socialism.

On November 26, 1974 a classified advertisement from Slavko Matković appeared in the German regional newspaper Hartzberger Presse (Hartzberg Press) with the statement “Ich bin Künstler (I am an artist) – Slavko Matković”.21 The project with the title Ich bin Künstler (Ja sam umetnik) was to be Matković’s most important art project, as he told Bálint Szombathy in a letter from November 12 of the same year: “I want this announcement published through all leading papers worldwide! The project is in progress already – including so far Canada, West Germany, France, England” (Milenković 2005, p. 57). This intervention cannot be labelled as performative in a narrow sense, it is rather the artist’s attempt to conduce a self-verification of his own artistic existence by establishing an imaginary dialogue with an unknown partner. This relatively simple act may be characterised as paradigmatic for the poetics of Slavko Matković, who, like few others, had interwoven his existence with his self-understanding as an artist. Matković belongs, according to Miško Šuvaković, to the tradition of such artist figures as Kurt Schwitters, Lajos Kassák or also Joseph Beuys, in whom also “after a particular moment the boundaries between the biographical, the concrete life and artistic production were lost (crossed, erased)” (Šuvaković 1996, p. 123).

Present text was an attempt to demonstrate and analyse various aspects of the international networking of Yugoslav experimental and post-object art scene in the 1970s as well as the ambiguities characteristic to the in-between position of Yugoslavia outside the dominating logics of the Cold War era. The case studies consulted in this paper show the complexity and plurality of the cultural exchanges and the reciprocal interlacing of these phenomena further how they were challenging a homogeneous view of cultural public spheres in real existing socialism. Internationalism is not to be seen here as an effort to connect with a dominant discursive practice, that of “Western” art, but far more as an expression of an artistic matter of course to form part of an international movement which has made its task to extend the limits of art and to leave behind and deconstruct the traditional late modernism, with all its ideological implications.

By focusing on selected conceptualist and performance practices in Yugoslavia during the 1970s, the essay aimed to challenge conventional models of East-West relations, and established a non-hierarchical point of view on the development of performance and ephemeral artistic practice alongside different trajectories of exchange, transnational collaboration, cross-border activities of artists, curators, and content.

The case studies had demonstrated that the development of Yugoslav post-objective art, of performance and body art, is by no means due to a belated uptake of Western universal practices, but rather is an expression of a simultaneous spirit of change, spurred by similar needs, which set itself up in opposition to the formal language of modernist objective art and its ideological cultural policy. It is worth noting that many of the examples cited here are not readable as direct aesthetic reactions to their specific contexts of creation, on the contrary, they were first and foremost reflections of the same contents which were dominant in the Western context. Institutional critique, a break with state artistic space in favour of ephemeral and performance forms of presentation, the transformation of one’s own body into artistic object or medium, were global strategies of the neo-avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s.

The dichotomy between East and West, the acting from a “limited”, often marginalized and precarious, second public sphere and the concomitant limitation on public dissemination also reveal the ambivalence of these highly innovative and internationally oriented epochs, as addressed here in the works of Szombathy and Matković. The internationalism of the Yugoslav neo-avant-garde, i.e. its unquestioned self-image of taking part in a universal emancipation movement on a par with the global centres of those years, is in retrospect to be viewed as a brief episode. Art theorist Igor Zabel, who in many of his writings has analysed East-West relations, which are usually understood as a relationship between centre and periphery, criticises that there is still only a very small number of East European artists whose status is recognised in the so-called West, and even if recognition succeeds, only those who act from within a Western context are “integrated”: “… The codification of the field and the construction of its history and tradition resulted in a marginalization or total ignorance of important eastern phenomena. For example, eastern avant-garde artists of the 1960’s and early 70’s simply do not exist in historical surveys of art of this time, except those who have moved to the West” (Zabel 2012, p. 28).

1Cf. the exhibition and its corresponding publication (Christ and Dressler 2010).

2The Information Bureau of the Communist (Parties) and Workers Parties.

3“The basic issue in the great quarrel of 1948 was very simple: whether Tito and his Politburo or Stalin would be dictator of Yugoslavia. What stood in Stalin’s way was Tito’s and hence the Yugoslav regime’s autonomous strength, based on the uniqueness in Eastern Europe of Yugoslavia’s do-it-yourself and armed Communist revolution and its legacy: a large Party and People’s Army recruited primarily on the basis of patriotic rather than socialist slogans, and the independent source of legitimacy as well as power which came from the Partisan myth of political founding” (Rusinow 1977, p 25).

4Cf. the OHO group was founded in Slovenia in 1966, the first artistic collective of the region, dealing with happening, performance and conceptual art.

5The most prominent artists are: Goran Trbuljak, Tomislav Gotovac, Braco Dimitrijević, Sanja Iveković, Group of Six Artists (Boris Demur, Željko Jerman, Vlado Martek, Sven Stilinović, Mladen Stilinović, Fedor Vučemilović).

6Cf. the group Crveni peristil.

7Even within the more narrow context of Belgrade only, one could list a large number of artistic groups that were active within the context of the “new artistic practice”: Ekipa A³, the informal group of six artists, the Mečgroup, Signalism (Signalizam), the Zrenjanin textualists, Group 143, among others (Unterkofler 2013, p. 53).

8Bosch + Bosch was founded there in 1969 by Bálint Szombathy and Slavko Matković.

9The groups KOD (1970–1971); (Э and (Э KOD were influenced by language philosophy, the Situationist Internationale as well as by politically engaged artistic practices.

10This suggested periodization is based on the founding date of the Slovenian OHO group, which marked the beginning of the neo-avant-garde in Yugoslavia and the date when the Belgrade-based Group 143 broke up, that was considered as the last coherent group of conceptual art.

11On the international nature of Yugoslav conceptual art see Šuvaković 2009, pp. 373–383.

12For his text The Poem of the Underground Youth Stands Novi Sad (Pesma underground tribina mladih novi sad) that should have appeared in the student magazine Index (this edition was banned), Bogdanović 1972 was sentenced to an 8 months imprisonment.

13Denegri (1978) mentions examples such as the collaboration of Slovenian group OHO and Walter de Maria in 1971 as well as the exhibitions that Braco and Nena Dimitrijević organized: At the Moment (in Frankopanska 2a in Zagreb) and In the another moment (Gallery of Students’ Cultural Centre in Belgrade), with the participation of Anselmo, Barry, Brown, Buren, Burgin, Dibbets, Flanagan, Huebler, Kirili, Kounellis, LeWitt, Weiner and Wilson. Furthermore, The Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb hosted the shows of artists like Buren, Boltanski and Messager. The Student Cultural Centre (SKC) in Belgrade became the venue for international meetings held in April from 1972 with guest artists such as Michelangelo Pistoleto, Jannis Kounellis, Gina Pane, Joseph Beuys, Andrew Menard and Michael Corris from Art & Language, John Baldessari; and critics such as Germano Celant, Achille Bonito Oliva, Filiberto Menna, Klaus Honnef, etc. The other aspect was the participation of Yugoslav artists in thematic exhibitions and big art manifestations like the Edinburgh Art Festival, the Biennial of Young Artists in Paris, Documenta in Kassel and Venice Biennial. The most notable examples are the following: group OHO in 1970 took part in the exhibition Information curated by Kynaston McShinea in MOMA, New York; OHO and Braco Dimitrijević exhibited at Aktionsraum 1 in Munich in 1971; Goran Trbuljak, Goran Đorđević, Marina Abramović, RašaTodosijević, Zoran Popović, Mladen Stilinović, Andraž Šalamun and Group 143 exhibited at the Biennial of Young Artists in Paris from 1973 to 1977; Braco Dimitrijević who attended postgraduate studies at St Martin’s School of Art in London from 1971 to 1973, exhibited at Documenta 5 and Documenta 6 in Kassel in 1972 and 1977. Marina Abramović who in 1976 left for Amsterdam and started working with Ulay, exhibited at the Venice Biennial in 1976 and Documenta 6 in Kassel in 1977.

14Between about 1972 and 1974 there was a very close collaboration between the American offshoot of the Art&Language group and the Belgrade-based conceptual and performance artist Zoran Popović and the art historian Jasna Tijardović. Both spent some time in New York between 1974 and 1975 and worked together with Art&Language. This is also where Popović’s film Struggle in New York, which documents the conflict within Art&Language, was made. In October 1975 three Art&Language members (Michael Corris, Andrew Menard, and Jill Breakstone) came to Belgrade and took part in a roundtable discussion arguing against the “cultural imperialism” of the USA.

15A noteworthy exception is the group exhibition of New Yugoslav Art, shown in 1976 in the Warsaw Galeria współczesnej and that was exclusively comprised of works in the spirit of New Art practice.

16According to Sveta Lukić this specific Yugoslav version of modernism developed after 1955 and carried the following characteristics: “Aestheticism dulls the edges, rounds up things, smothers a more specific, further divergence. Theoretically empty, definitely loose in practice, it forms more neutral works. It is therefore an art form that entailed elements of socialist everyday reality, but fused these elements with a modernistic and partly abstract vocabulary of form as the dismissal of socialist Soviet-influenced realism” (Lukić 1963, p. 67).

17Era Milivojević did not take part in the Edinburgh exhibition.

18The so-called Motovun meetings (Motovunski likovni susreti, 1972–1984) were a forum for intensive international exchange between Yugoslav and international New Art. Contacts with Italian experimental art were especially important.

19The exhibition was afterwards also shown in Dublin, Belfast, Leigh and Glasgow.

20“Photo performance” is a name for anonymous, private or public actions of an artist that are not intended for a set audience (only accidental viewers). They are instead planned for a photographic documentation of the performance event (Šuvaković 2005, p. 158).

21The ad was handed in and paid for by Dejan and Bogdanka Poznanović, based on instruction by Matković. The Poznanovićs were at that time on their way to Documenta in Kassel.

Beuys, J. (1974). I am Searching for Field Character. In: R. N. J. Christos M. ed., Art into Society, Society into Art: Seven German Artists. 1st ed. London: Institute of Contemporary Art.

Blackwood, J. (2010). Richard Demarco and the Yugoslav Art World in the 1970s. In: E. McArthur and A. Watson, eds., Ten Dialogues: Richard Demarco and the European Avant-Garde. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Royal Scottish Academy.

Christ, H. D. and Dressler, I., eds. (2010). Subversive Praktiken: Kunst unter Bedingungen politischer Repression. 60er-80er/Südamerika/Europa. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Württembergischer Kunstverein.

Demarco, R. (1972a). Letter to Oto Denes [typed document]. Available at: www.demarco-archive.ac.uk (Accessed June 25, 2017).

Demarco, R. (1972b). Report on His Visit to Yugoslavia 4th – 10th December 1972 [typed and page-numbered document]. Available at: www.demarco-archive.ac.uk (Accessed June 25, 2017).

Demarco, R. (1976). The Richard Demarco Gallery Edinburgh Catalogue to the 1966–1976 10th Anniversary Exhibition of Paintings, Sculpture, Drawings and Prints Acquired by Scottish Public and Private Collections Through the Gallery and a Ten Year Record of the Gallery’s Activities. 1st ed. Edinburgh: The Demarco Gallery.

Denegri, J. (1977). Za strukturu direktnih uključivanja. Umetnost, (55), pp. 42–43.

Denegri J. (1978). Art in the Past Decade. In: M. Susovski, ed., The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia 1966–1978. 1st ed. Zagreb: Gallery of Contemporary Art, pp. 11–12.

Denegri, J. (2003). Studentski Kulturni Centar kao umetnička scena. 1st ed. Belgrade: SKC.

Denegri, J. (2004). The Contemporary Serbian Arts Scene in an International Context. Available at: www.oktobarskisalon.org/45/jesakat_e.htm (Accessed June 12, 2017).

Lampe, J. R. (2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There was a Country. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lukić, S. (1963). Socijalistički estetizam: Jedna nova pojava. Politika, April 28.

Marcuse, H. (1969). An Essay on Liberation. 1st ed. Boston: Beacon Press.

Milenković, N. (2005). Ich bin Künstler – Slavko Matković. 1st ed. Novi Sad: Museum of Contemporary Art.

Rusinow, D. (1977). The Yugoslav Experiment 1948–1974. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Šuvaković, M. (1996). Asimetrični Drugi. 1st ed. Novi Sad: Prometej.

Šuvaković, M. (2003). Art as Political Machine. In: A. Erjavec, ed., Postmodernism and the Postsocialist Condition: Politicized Art Under Late Socialism. 1st ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 90–135.

Šuvaković, M. (2005). Performing of Politics in Art – Transitional Fluxes of Conflict. In: N. Milenković, ed., Szombathy Art. 1st ed. Novi Sad: Museum of Contemporary Art Novi Sad.

Šuvaković, M. (2008). Student’s Cultural Centers as Reservations. Available at: www.prelomkolektiv.org/pdf/catalogue.pdf (Accessed June 5, 2017).

Šuvaković, M. (2009). Eine handfeste Geschichte aus dem Kalten Krieg: Internationale Referenzen der Konzeptkunst im sozialistischen Jugoslawien. In: H. Fassmann et al., eds., Kulturen der Differenz – Transformationsprozesse in Zentraleuropa nach 1989. 1st ed. Vienna: Vienna University Press, pp. 373–383.

Unterkofler, D. (2013). Grupa 143: Critical Thinking at the Borders of Conceptual Art 1975–1980. 1st ed. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik.

Ward, F. (2010). Marina Abramović – Approaching Zero. In: A. Dezeuze, ed., The ‘do-it-yourself' Artwork: Participation from Fluxus to New Media. 1st ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 132–144.

Zabel, I. (2012). We and the Others. In: I. Španjol, ed., Igor Zabel: Contemporary Art Theory. Zürich: JP Ringier.