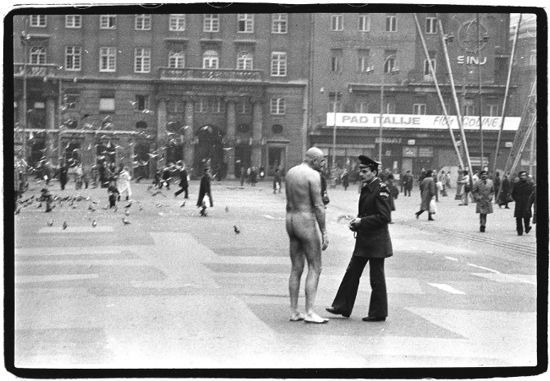

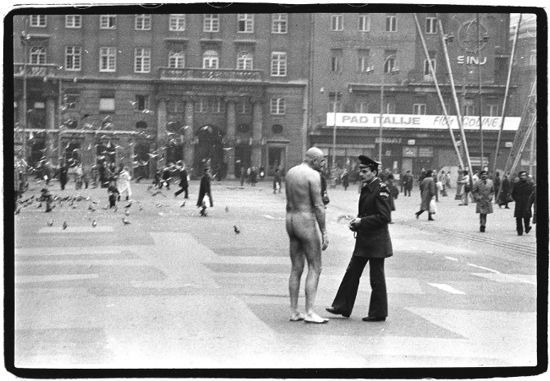

Figure 6.1 Tomislav Gotovac, Zagreb, I love you!, 1981.

Photo: Ivan Posavec, Collection Sarah Gotovac. Courtesy: Tomislav Gotovac Institute, Zagreb.

On the few photos documenting the performance Lying Naked on the Asphalt, Kissing the Asphalt (Zagreb I love you) [Lezanje Gol Na Asfaltu, Ljubljenje asfalta (Zagreb, Volim Te!)], by the Croatian artist Tomislav Gotovac, we see a naked man walking through a crowded street. From time to time he prostrates himself on the asphalt and performs the action of kissing the ground. As with almost all of his performances and actions in public space, this one had happened at 12 o’clock (13 November 1981). Placed in an urban landscape, the artist displayed an “intimate, almost loving, relationship with the city” (Piotrowski 2011, p. 374), whereby his nakedness intensifies this relation, but also radicalizes the tension between the apparently “natural/authentic” (and singular) body and the other bodies, wearing autumn cloths. That such behaviour is regarded with suspicion as antisocial and that it is directed against the conventional behaviour in public space, is confirmed by the fact that only after seven minutes, Gotovac had been arrested by a police officer who dragged him away and charged him with a fine for disturbing public order. The trajectory from the doorway in Ilica Street 8, where he undressed, to the main square, where he had been taken into custody, flashes out a volatile and grotesque corporeality that is opposing the hypocrisy of the public order. “The naked body in the public space, in my town,” claimed the artist, “is a blasphemy, an insult to the petit-bourgeois” (Denegri 2003, p. 273). The gesture of stripping off clothes on the town square makes forces and rules which structure the public space and public behaviour visible.

Analysing the complicated relations and dialectics between the body, the performance and the politics of public space in the oeuvre of Tomislav Gotovac, this text aims to situate his performances within the contours of a proletarian public sphere, as conceived by Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt in their book Public Sphere and Experience. Toward an Analysis of Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere [Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung. Zur Organisation von bürgerlicher und proletarischer Öffentlichkeit, 1972]. As Kluge and Negt observe, the proletarian public sphere stimulates us to think of it as a counter-public1 directed against the bourgeois public sphere, which is structured around the blocking of experience of the proletariat. At the same time, the “proletarian publicity” should be imagined “as a form of resistance against real subsumtion under capital” and should lead to a “proletarian cultural revolution” (Negt and Kluge 1993, pp. 185–186). Following that line of reasoning, it seems plausible to assert that Kluge and Negt invoke the proletarian public sphere to be able to investigate the contradictions of the bourgeois public sphere, which are grounded in the capitalist mode of production. However, since the proletarian publicity “has no existence as a ruling public sphere” (ibid., p. xliii) it needs to be reconstructed from historical fissures, marginal cases or isolated initiatives, which in the context of present text, will be the performances of Tomislav Gotovac.2

Figure 6.1 Tomislav Gotovac, Zagreb, I love you!, 1981.

Photo: Ivan Posavec, Collection Sarah Gotovac. Courtesy: Tomislav Gotovac Institute, Zagreb.

Understood as one of the modes of organizing and producing social experience, the concept of the proletarian public sphere outlines a methodological possibility to grasp the public sphere not as a unified, homogeneous and autonomous substance, but focusing on its mechanisms of exclusion. Also, in relation to the structure of production and the sexual economies, it can be stated that the bourgeois public sphere manifests itself by concealing both the process of production (labour) and the exclusion of eroticized, explicitly gendered bodies. For film historian Miriam Hansen this is precisely how the public sphere is organized:

The bourgeois public’s claim to represent a general will functions as a powerful mechanism of exclusion: the exclusion of social groups, such as workers, women, servants, as well as vital social issues, such as material conditions of production and reproduction, including sexuality and childrearing – the exclusion of any difference that cannot be assimilated, rationalized and subsumed.

(Hansen 1993, p. xxviii)

Consequently, the analytical focus on the problem of gender and labour in the performances of Tomislav Gotovac should unwrap a double argumentative procedure, which exposes the issue of exclusion in relation to the prevailing gender and labour politics.

To counteract and oppose the bourgeois public sphere to the proletarian, one should make clear that in the case of socialist Yugoslavia it is not easy to hold on to one single concept; its public sphere has to be thought dialectically: as a dynamic and at times contradictory3 process. Abandoning the system of state socialism, which had been “copied” after the Russian model, political authorities in Yugoslavia after 1950 started to experiment with a new type of socioeconomic organisation called workers’ self-management socialism, meaning that workers would take control over the conditions and products of their labour. In its idealism, this social model suggested the decline of state and the situation in which the proletarian sphere would become the only public sphere, just as in state socialism “the public sphere was explicitly – in official terms – the state itself” (Miles 2009, p. 133). However, instead of a progressive development towards class equality and a socially more even development, the ruling elite had embraced all characteristic elements and rituals of the Western bourgeoisie, so that the antagonism between proletarian and bourgeois public spheres, as the state was moving towards its decline after Tito’s death in 1980, became more visible. It is in the light of these historical conditions (and contradictions) that the proletarian public sphere, perhaps, can be mapped as a counter-public which had been slowly withering away as the socialist system was collapsing under unresolved tensions, both on the level of national and economical relations, as well as due to the shifting power between the “Western Bloc” and the USSR.

Another reason to analyse the performances of Tomislav Gotovac within the concept of the proletarian public space is the fact that the artist himself considered his first happening/action to be those ten years he spent working as a clerk at the National Bank and at a hospital in Zagreb. When Kluge and Negt observe that the proletarian public sphere is “none other than the form in which the interests of the working class develop themselves“ (1993, p. 94), the implications are that these interests have been eroded and obscured by the bourgeois public sphere. The solution to this mutilation and repression, Kluge and Negt would argue, is to establish an alliance between the workers and the intelligentsia (understood here foremost as artists). The art of Gotovac could be regarded as establishing such an alliance.

The commitment to reconstruct the repressed space of the proletariat circles around the attempt to think the (urban) space relationally and dialectically, with regard to the political, economic and ideological shifts which signify the transition from socialism to present-day neoliberalism (that in the case of former Yugoslavia unfolded in a terrible warfare and total commodification). In line with this argument, it can be said that the subversive use of the body in performative and conceptual art practices of Southeastern Europe in the second half of the twentieth century confers an interpretative frame. This frame depends upon reconstructing the features of public and counter-public in socialist Yugoslavia, particularly when the public sphere is addressed as a site of exclusion and not of equality, brotherhood, and unity as it was officially declared. If that was the case, as most Yugoslavian citizens used to believe at a time, we could ask what has been excluded, omitted or removed from the public sphere? What would have happened if these hidden things, actions, practices, themes and bodies regained their visibility and reentered “the scene”? And ultimately, how does the visibility of repressed subjectivities and themes affect and alter concepts of identity, representation and power structures?

Situated among different media – photography, experimental film, collage, ready made, happening, movie acting, public actions and performance art – the work of the Croatian artist Tomislav Gotovac serves as a model of a neo-avant-garde practice4 from Southeastern Europe in the second half of the twentieth century, which fundamentally changed the notion of the public sphere and its constituting private/public dichotomy. His naked body moving through public space, as an art event, radically intervened in the order of real existing socialism, whose corporeal image is best mirrored in the performance of the collective: the semi-naked athlete’s body performing during the so-called celebrations of the Days of Youth.5 In contrast to the uniformed and well-trained virtuoso bodies, the artist with his naked singular figure, whose stature, presence and image is seen as an interruption of (these) behavioural norms and proscribed roles, generates a fissure in the symbolic order of the public space. On the other hand, threatening to dismantle the private/public dichotomy by staging a grotesque corporeality, Gotovac moves within the neo-avant-garde logics of trespassing the clear division between art and life.

Furthermore, I will question how the public sphere, once it is examined on the backdrop of performative interventions, can be linked to issues concerning modernist ideology of the artwork as an autonomous and self-enclosed entity, cut off from social or political reality. If we agree that the demand for an autonomy of art – as it has been shaped already within the philosophy of Enlightenment and continued to be fostered in the modernist project – has also been a central element in the constitution of the bourgeois subject, it could be asked what happens once art escapes from the safe zone of institutions and (petit-bourgeois) conventions? What kind of public sphere emerges out of the act of trespassing the (volatile) border that separates artistic practice from social and political reality?

In an attempt to answer these intricate, even paradoxical questions, I will first briefly outline the concept of public sphere developed by Jürgen Habermas, later criticized by Nancy Fraser. The decision to weave my arguments around these two positions is motivated dialectically, since Fraser’s text can be seen as an antithesis to the seminal work of Habermas. Moreover, since an important part in Fraser’s argumentation is grounded in reflections on gender and the “bourgeois masculinist conception of the public sphere” (1990, p. 60). I want to be clear about gender relations that have fundamentally structured and determined the public sphere in Yugoslavia. These two positions will, thus, serve as a springboard to situate the naked actions in relation to the moral law which underlies the functioning of public space.6 The intention is to show how Gotovac’s actions confirm that the question of public space is linked to operations of evicting and policing, how the event of exposing the naked body can potentially be regarded as subversive. The second line of my argument will revolve more specifically around the notion of a proletarian public sphere, reflected in the actions of performing colportage labour at the same site where he once staged his naked body. In interpreting the dialectics of the public sphere in socialist Yugoslavia between its bourgeois and proletarian configuration what will be mapped is the dissipation of publicity and the commodification of labour. And maybe it will be in these performed spatialities of nakedness, gender politics and labour that a proletarian public sphere will (re)gain its visibility.

Besides the scandalous naked body, the performance Lying Naked on the Asphalt, Kissing the Asphalt (Zagreb I love you) had been devised as a homage to the film Hatari (directed by American filmmaker Howard Hawks in 1962). Identifying himself with the image of the black rhinoceros7 that at the beginning of the movie was chased unsuccessfully through the African wilderness, Gotovac seeks to produce an image of the artist being persecuted as well as deprived of the freedom of movement. Using his body as a “ready-made” (Denegri 2003, p. 272), the artist expresses a confrontational and anarchistic gesture which aims to confront authorities (and public morals) with a demand for freedom of behaviour. From a topological perspective it is significant to notice that one of the institutions he will pass on his way to the square is the Church of Wounded Jesus. Invoking an image of both being an animal and a priest going through the act of consecration,8 Gotovac amasses together a corporeal scene abundant with references and subversive meanings. In the light of these observations, it may be asked what is, or rather what could be the relationship of the naked body, with all its visible and invisible references, and the public sphere? What kind of (social) experience could such a naked body generate?

To be able to comprehend (political) implications of such an artistic action in the context of socialist Yugoslavia, I shall turn my attention to the specific organization and politics of its public space, focusing primarily on the mechanisms of police force. As it was elaborated by Jürgen Habermas, the spheres of public authority are sharply distinguished from the private realm, whereby the public sphere “is coextensive with public authority” (1989, p. 30). Thus, the public sphere is always the result of a certain constellation and distribution of power and mechanisms of control. As a maintaining force of the social order, the public sphere and the public space, the police, in Rancière’s terms, “is thus first an order of bodies that defines the allocation of ways of doing, ways of being and ways of saying, and sees that those bodies are assigned by name to a particular place and task” (1999, p. 29). Once a body steps out of its assigned place and starts behaving against the social order, a new political constellation happens, insofar we regard political activity to be: “whatever shifts a body from the place assigned to it” (ibid., p. 30) which in the context of this text would mean that the naked body is not allocated anymore only in the private intimate realm, but becomes visible in public space.

In a regime like the one in Yugoslavia during the socialist era, followed by the Yugoslav national army, the police had been one of the pillars of social order. However, unlike other countries of the former Warsaw Pact, where the secret police (Stasi, Securitate, KGB, etc.) was controlling almost every aspect of social and political life until the fall of the Berlin Wall, Yugoslav authorities started experimenting with a more liberal version of socialism that implied a gradual “opening of the country” towards the West. This tendency could have been read by notable shifts embracing cultural products from Western Europe and the US. The consequence of such liberal (economical and cultural) politics resulted in the opening of a number of student cultural centres across Yugoslavia in cities like Ljubljana, Zagreb, Belgrade or Novi Sad, where an alternative cultural scene was beginning to flourish. Having in mind artists like Mladen Stilinović, Vlado Martek, Željko Jerman, Sanja Iveković and Tomislav Gotovac, the Serbian critic and theoretician Miško Šuvaković observes, “In fact, in the 1960s, Croatian culture became the only culture in the socialist world in which neo-avant-garde art became the dominant institutional art” (2003, p. 121).

Nevertheless, art practices, which can be labelled as radical interventions in public space, such as the performances by Gotovac or the performance Triangle (Trokut, Zagreb, 1979) by Sanja Iveković, operated on the margins of the official art system and exposed a different understanding of the public sphere and socialist society. During one of Tito’s visits to Zagreb on the 10th of May 1979, which had been followed by a usual security procedure and demanded that all the balconies and windows on Tito’s route would have to be closed, Sanja Iveković (in Triangle) violated the protocol and sat on her balcony. Besides drinking whiskey, she also simulated masturbation, which had been seen by a nearby secret police agent (equipped with binoculars).9 The performance had ended after 18 minutes with the police officer coming to Iveković’s apartment with the demand: “that all objects and persons should leave the balcony” (Marjanić 2014, p. 579). Being situated in a liminal space between the private and the public, this example, on the one hand, demonstrates that the private sphere, too, is subjected to protocols of surveillance, eviction and policing. In other words: the border between the private and the public is not a stable nor is it a given, natural order; it is a social construction, reflecting power (and gender) relations. On the other hand, the role of police, as can be witnessed in both of the examples of Gotovac and Iveković, is directly connected to the function of preserving morality. As a form of legitimized and institutionalized violence, the existence and function of police testifies that the public sphere mirrors the organization of the state, that it re-embodies and represents the state apparatus.

What is debated in these two examples is the dichotomous organization of public space, where the private realm is cut off from the public. The naked and eroticized body, thus, had a threatening effect and its presence in public space had been charged with political consequences that were expanding the notion of art and – by displacing the borders between the private and the public – were questioning the idea of public itself, as well as the idea of the autonomy of art. At this point, it must be noticed that the idea of the public “in this narrower sense was synonymous with ‘state-related’; the attribute no longer referred to the representative ‘court’ of a person endowed with authority but instead to the functioning of an apparatus with regulated spheres of jurisdiction and endowed with a monopoly over the legitimate use of coercion” (Habermas 1989, p. 18). For Habermas the substance of the public is generated through the process of private people addressing public authority, which transformed the manorial lord’s feudal authority “into the authority to ‘police’” (ibid.). So far, the role of the police is to protect and watch over the constituting public/private dichotomy, making sure that every threat to the existing order is immediately suppressed, that everybody is assigned to his or her proper place and behaves within the framework of (petit-bourgeois) morality.

In this scenario the contours of a counter-public will occur in moments when structures of the official public sphere are unmasked, unveiled and demystified.

Any performative action, provocation and intervention in public space that radically sets in motion its (libidinal and sexual) organization necessarily operates with(in) political signifiers and can contribute to a critical reflection on the structures of publicity. In her text, which conceives a critique of the bourgeois vision of the public sphere, Nancy Fraser focuses on mechanisms of exclusion grounded in gender differences. She writes: “This process of distinction, moreover, helps to explain the exacerbation of sexism characteristic of the liberal public sphere; new gender norms enjoining feminine domesticity and a sharp separation of public and private spheres functioned as key signifiers of bourgeois difference from both higher and lower social strata” (1990, p. 60). Even though it might be said that this concerns primarily the invisibility of women in public space, i.e. their assigned position to the private realm of domestic interior or their semi-naked, allusive appearance as a desirable decoration of public exterior, the nude performance of Gotovac and the masturbating action of Sanja Iveković10 challenge this separation, foregrounding disobeying bodies that have displaced the borders and have proven that morality is the instrument of police and one of the essential features of publicness.

When art historian Bojana Pejić in her study on the performance Triangle proposed that Triangle “announces an emergence of the democratic public space” (2006, p. 18), one is tempted to ask whether the same could also be applied to the performances of Tomislav Gotovac? Whether both Iveković and Gotovac anticipate the transition, metamorphosis and structural changes of the public sphere: from its proletarian form to its bourgeois, democratic model? Can the second public sphere be reconstructed from the dissensual and antagonistic activity of the performances and their potential to expose a reflective space about the organization and politics of the altering publicness in Socialism? Are we, perhaps, confronted with a paradox, that the birth of democratic public space is structurally the moment of the dying away of the proletarian public sphere? Finally, would it be plausible to locate the counter-public sphere within that paradox?

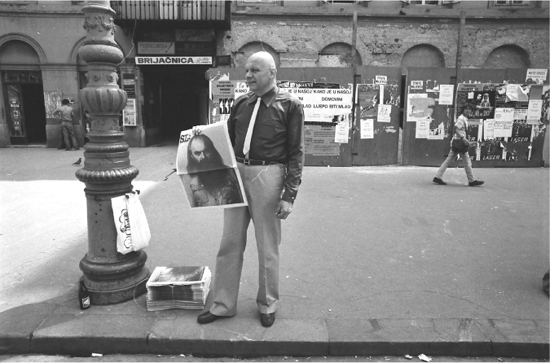

Between 1981 and 1984 Gotovac had performed a series of performances in which the action consisted in selling newspapers, which, among other things, contained images of his nude performances. After the first action in 1981, where he would stand on the main square (at that time called Square of the Republic) and would sell the student newspapers Studentski list and Polet, in 1984 he would change costumes on a weekly basis, altering his identity as follows: The Mask of Death, Mummy, Street Cleaner, Sickle, Hammer and the Red Star, Santa Claus, Chimney-Sweep. Performing on the same site where he had performed Zagreb I love you, Gotovac focused on the relation between the individual body and the accidental passer-by, who became the witness of a spontaneous and contingent street theatre of fictionalized labour. The artistic strategy of changing, challenging and appropriating identities targets the notion of fixed identities and entails a conscious deconstruction of the politics of representation. In that regard, these performances of masquerade might be seen as a statement about the theatricality of the public sphere. What I would like to focus on here is the visibility of labour in public space and the figure of the news-vendor or the sandwich-man, perhaps being “the last incarnation of the flâneur” (Buck-Morss 2006, p. 41).

In an exhibition with the title Newspaper Art by Tomislav Gotovac, in Zagreb 2014 curated by Darko Šimičić, this aspect of his work gained visibility, since the audience could see newspapers in which the documentation of the performances and actions had been published. Besides the samples of the actual newspapers, showcased were also photos from the 1981–1984 performances, which made it clear that Gotovac had a conscious approach to the medium of newspapers, using it to mediatize and archive his otherwise ephemeral actions. Analytically, the colportage-performances can be used to focus on the notion of the public sphere from the perspective of masquerade, fiction and (in)visibility of labour. If the contours of a second public sphere (as a counter-sphere opposing the hegemonic and homogenous aspects of the public sphere) can be redrawn on behalf of the queer corporeality, made visible by the performance of the naked body, my second example shifts the attention to issues of labour and the way Gotovac was (mis)using the apparatus of mass media in order to collapse the dichotomy of art and life, turning performance into a social instrument with political and ideological implications.

Figure 6.2 Tomislav Gotovac, Newspaper Vending action, 1981, Collection Sarah Gotovac.

Courtesy: Tomislav Gotovac Institute, Zagreb.

In both cases the emphasis is on the suppressed and excluded: while the naked body refers to issues of explicit sexuality, the unconcealed presence of labour performed in the public space brings forth the possibility of reflection on the position of the working class. In this context, it might also be reminded that the artist considered his first performance to be the work he had been doing from 1956–67, when he was employed as a clerk. As if following the task of the intelligentsia to “destroy the eroded capitalist basis for legitimation” (Kluge and Negt 1993, p. 94) of bourgeois society, which can only be achieved if the intelligentsia and the working class form “an alliance” (for Kluge and Negt this is the fundamental prerequisite of the proletarian public sphere), Gotovac is not only trespassing the borders between art and life, but also the one considering the division between manual, artistic and intellectual labour.

Being the “institutions and instruments of the public sphere” (Habermas 1989, p. 83) the development of the press11 and the distribution of newspapers is an important element in the shaping of the (bourgeois) public sphere. So far the colportage performances seem to underline not only that the public sphere is determined by circulation of newspapers and the existence of a public opinion created through them, but that it has also been the birthplace of the stratum of bourgeois people and of the capitalist mode of production. Even if it might sound paradoxical that in times of socialism we could identify something as the stratum of bourgeois people, simply because the whole project officially aimed at affirming working class values and the working class ideology, the bourgeoisie12 did not cease to exist. The public sphere of socialist Yugoslavia can be viewed as an expression of the class interest13 of the Bürger and as such it depends upon the reproduction of private ownership.

As a historical counter-concept to the bourgeois public sphere, the proletarian public sphere – following Negt and Kluge – is modelled on suppression of the interests of workers, who are surviving “as living labour power” (1993, p. 57). Other elements that determine the experience of the proletarian public sphere in contrast to the bourgeois counterpart are “the bourgeois as character mask” and the “public sphere as a product”, in which the process of production is subjected to disintegration and devaluation (ibid., p. 56). If the performance of the naked body made manifest the gender politics of the public sphere, the colportage performances seem to foreground the suppression and exclusion of (living) labour under the risk of commodification, the division of labour (manual and intellectual), the demise of public property and the appropriation of public good. When Gotovac performs his newspaper vending, changing masks and costumes, what this act brings to our attention is not only the mask and the costume character of the public sphere, but a complicated notion of labour, undergoing drastic alterations, especially when reflected today, in the age of deregulated economy of Postfordism.14 The image of a masked worker, I argue, unleashes signifiers of alienated labour, which is turning into commodity,15 blocking experience of belonging to society and moving further away from the idea of workers’ self-management. Hence, embodying the role of a fictional worker, Gotovac is addressing the illusion of Yugoslavian socialism, whose ideological premises were formulated around the notion of self-management and the belief that the working class will win (or has already won) the class struggle.

To be able to circumvent what such a performative procedure might entail in terms of a social/class dynamics, I shall draw upon one last theoretical position, which situates the figure of the worker in the economically changing urban landscape. When analysing the concept of the flâneur in Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project (Passagen-Werk) and in relation to the sandwich-man and the prostitute,16 Susan Buck-Morss notes that all these figures revolve around the dialectical image of the proletariat, associated with poverty and debasement. Although Buck-Morss writes about Paris in the 1930s, Zagreb (at the beginning of the 1980s) seems to offer a similar scene of consumer goods overflowing the public space and workers without jobs: “The sandwich-man was a denigrated, yet familiar figure in Paris in the 1930s, one which would have entered the perceptive range of most city dwellers. Human billboards, they advertised and publicized the products and events (cinemas, store sales) of bourgeois consumer culture” (2006, p. 42). As the female alter ego of the flâneur and the sandwich-man, the prostitute signifies the commodification of desire, the transformation of erotic life and the advent of a type of labour in which commodity coincides with the act of selling, meaning that in times of increased unemployment, the worker has to make him/herself “attractive to the firm” (ibid., p. 51). In all of these cases (the flâneur, the sandwich-man and the prostitute), we are faced with a vanishing sphere of living labour, whose protagonists are exposed to coercion and eviction: “For the politically oppressed (a term which this century has learned is not limited to class) existence in public space is more likely to be synonymous with state surveillance, public censure and political constraint” (ibid., p. 48).

In the light of the above-examined thesis one final problem that needs to be resolved is how to read the colportage performances in the context of the economic crisis, which Yugoslavia was facing at that time? Are they (the performances) to be regarded as symptoms of the decaying public (bourgeois) sphere or is it plausible to read them as an attempt to create a counter-sphere, which calls forth the utopia of erased division of labour and gender/class equality? If Gotovac did succeed in exposing the exclusionary mechanisms of the public sphere both with regard to gender politics and the embodiment of labour power as commodity, can we consider his performances as calling upon a proletarian sphere? As Kluge and Negt make very clear, the function of the proletarian public sphere “is to protect individuals from the direct influence of bourgeois interests and ideologies” (1993, p. 61). However, the authors also insist that a proletarian public sphere is something yet to be created, that it exists only in the form of potentiality and that it foremost has to be thought as a horizon of experience not subsumed to the public sphere of the bourgeoisie.

Within the logic of this argument, Kluge and Negt argue that the fragmented division of labour is one of the first issues that needs to be transformed and what is at stake is “the liberation of the imaginative faculty, of sociological reality” (ibid., p. 128). Applying these demands to the colportage performances, we might come to a conclusion that Gotovac is perhaps also aiming at this: to set in motion a labour of fantasy (and fiction), which reveals hidden social antagonism and demystifies modes of production, grounded in alienated experience of hyper-production of commodities and the commodification of public space. At the same time, what is happening is also a process, which can best be described as “commodification of fantasy” (Jameson 1993, p. 67). Through the use of masks and costumes, Gotovac not only operates within a procedure of estrangement, he also reduces labour to fiction and signs that recall the realm of popular17 culture and mythical figures. What emerge before our eyes are, thus, dream images of reified, fragmented and alienated labour, which block experience and the fulfilment of the proletarian sphere. At the same time, the performances are foreshadowing the collapse of the socialist system and the death of Yugoslavia.

In a trajectory from the naked body to its costumed, fictionalized and masked double, Gotovac expands the space of artistic practice, crossing the border between art and life, whereby the consequences are overtly political, touching upon issues of gender representations and the commodification of labour in socialist Yugoslavia. The issue of art being a depoliticized and autonomous activity, as it had been conceived within the aesthetic regime of enlightenment,18 needs to be questioned radically, since it operates against the set of dichotomies which kept the sphere of art separated from social and political reality. A similar binary structure may also be identified regarding the constitution of the public sphere, whence the concept of autonomy, as Habermas compellingly shows, is reserved for private people and property owners. Thus, the demand for an autonomous art can only be formulated within the logic of private ownership and within the ideology of the bourgeois class, whose public sphere is carefully policed and fragmented. On the other hand, the approach towards a proletarian public sphere, although it is not yet to be located, might be mirrored in Gotovac’s performances of labour, which not only prefigure the reification (and commercialization) of vital human labour and art, but demonstrate how the public sphere will be devoured and colonized by images and consumer goods imported from the West. Yet both the performances of the naked body and newspaper vending manoeuvre within ambivalent signifiers, which announce the vanishing of the public sphere and the displacement and deferral of the proletarian publicity. And, perhaps, it is in this dialectical in-between of the proletarian and the bourgeois public sphere that a space of critical reflexivity emerges, a space in which we can, retroactively, read and decode the dream images of a collapsing publicity.

1In the context of the present volume, the idea of the “second public sphere” is tested in relation to the “proletarian public sphere”, which for Negt and Kluge is synonymous with the notion of a “counter-public” (Gegenöffentlichkeit). As a conceptual framework, the discursive development of a counter-public serves the purpose of emphasizing a “critical and oppositional public sphere”, that “might project an alternative organization of the public sphere” (Hansen 1993, p. XVI). In the case of former Yugoslavia, however, the problem resides in the fact that in comparison to other countries beyond the Iron Curtain, one cannot easily detect or reconstruct a second public sphere oppositional to the first public sphere. Also, having in mind the fact that at the times when Gotovac was conceiving his performances, the Yugoslav political, economic and social sphere had been organized around the concept of the so-called worker’s self management, emphasizing the proactive role of workers in terms of ownership and decision making, I thought it would be plausible to approach the problem manoeuvring with the ideas of Negt and Kluge.

2Since Kluge and Negt do not provide a particular example of the proletarian public sphere, but discursively circle around various problems, social and media constellations, leaving it to the reader to imagine and conclude how a proletarian publicity would look like, it seemed to me that the performances (such as the one described above) might set down a situation (and provide examples), which can be used to test their otherwise vague and abstract thesis. In contrast to the way the public sphere has been understood and scrutinized in the works of Jürgen Habermas and later on criticized by e.g. Nancy Fraser and Bruce Robbins, Kluge and Negt seem to offer a more speculative framework, which – because of its conceptual openness and interpretative potentiality – is suitable to address the dialectics of the public sphere with regard to the performances of Tomislav Gotovac.

3Such a dialectical approach seems even more suitable having in mind the context of the present publication and the question about the second public sphere in Eastern Europe under socialism it aims to grasp. In the case of socialist Yugoslavia, one encounters a difficulty of a sharp distinction between the official culture (public sphere) and subversive art practices (second public sphere), simply because most of the art practices in Yugoslavia since the 70s had been supported by state (art) institutions.

4The neo-avant-garde practice refers to a number of artworks and artistic strategies that have gained significance in the 70s and 80s and which can be seen as following the models established already by the avant-garde movement of the 20s and 30s.

5The Day of the Youth was a collective mass choreography in former Yugoslavia, which was held every year on the 25 May, on the occasion of Tito’s birthday. As such, the event can be seen as an example of something the dance theoretician Andrew Hewitt labelled “social choreography” which “ascribes a fundamental role of the aesthetics in its formulation of the political.” (Hewitt 2005, p. 3).

6Risking the danger of being reductionist, not surveying the difference between “public sphere” and “public space” in its totality, it might still be important to define the terms public sphere and public space. In the first case, the term public sphere denotes a whole set of practices, discourses, technological, political means and media, which constitute one society, particularly in its communicative aspect. As such, the public sphere can be seen as a more abstract and general term, which does not necessarily evolve in a real existing spatiality. In the latter case, public space, as it will be used in the text refers to a physical, material and spatial setting: the central square in Zagreb. Thinking this difference further with Jacques Rancière, who will be important for the analysis of the relation between police and the public space, it can be speculated that politics is to be conjoined with the public sphere, whereas police is the regulatory mechanism of public space.

7Writing about the performance, ethnologist and performance art scholar Suzana Marjanić observes that Gotovac evoked the image of the rhinoceros as a “symbol of the artist running away from the police state” (Marjanić 2014, p. 463).

8The artist himself said several times that with the act of lying down horizontal on the pavement, he actually paraphrased the gesture of the priest during consecration (Marjanić 2014, p. 463).

9What this example clearly foregrounds in terms of the conditions of the emergence of public space, is the power of visual control, which is embodied in the male gaze.

10The critic Bojana Pejić claims that with the image of the “woman at the balcony”, Sanja Iveković establishes a topography of outside/inside, private/public as well as the border of watching/being watched: “The woman at the balcony is the mise en scène, that induces gender that it is written in the dialectics of the private and public” (Marjanić 2014, p. 579).

11For Habermas the development of the press is a key event within the public sphere’s emergence: “Because, on the one hand, the society now confronting the state clearly separated a private domain from public authority and because, on the other hand, it turned the reproduction of life into something transcending the confines of private domestic authority and becoming a subject of public interest, that zone of continuous administrative contact became ‘critical’ also in the sense that it provoked the critical judgment of a public making use of its reason. The public could take on this challenge all the better as it required merely a change in the function of the instrument with whose help the state administration had already turned society into a public affair in a specific sense – the press” (Habermas 1989, p. 24).

12While the working class people (in Zagreb and Belgrade) were living mainly on the outskirts of towns in big grey building blocks, the intellectuals and elite of the ruling party lived in luxurious villas and private houses on the hillside. This example of the difference in the housing politics/environment makes evident that the social antagonism between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat can also be identified and read spatially.

13Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge make this very clear when they write about “[t]he public sphere as the organizational form of the bourgeoisie” (1993, p. 54).

14A thorough analysis of the condition of labour in Postfordism, especially in relation to the concept of bio-politics, is given in Virno 2007.

15From a historical and economical point of view, it is important to have in mind that the period between 1981 and 1984 in which the colportage performances took place, is the moment when Yugoslavia entered a continuous crisis, which resulted in the growth of unemployment and increase of foreign debt. Not being able to find a successful economic formula and with unresolved national conflicts, enhanced by the downfall of the Soviet Bloc, Yugoslavia was slowly collapsing under the double pressure of capitalism and nationalism.

16Similar to a prostitute that is selling her own body (work), the artist is selling newspapers with his own work/body.

17It should be underlined that the invasion of images of American cultural products and products from the so-called Capitalist West, which started in the mid-sixties, had an everlasting influence on altering the public space.

18It is interesting to see how the request for an autonomy of art had happened simultaneously with the emergence of the bourgeois public sphere in the late eighteenth century.

Buck-Morss, S. (2006). The Flâneur, The Sandwich Man, The Whore: The Politics of Loitering. In: B. Hansen, ed., Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. 1st ed. New York; London: Continuum, pp. 32–66.

Denegri, J. (2003). The individual Mythology of Tomislav Gotovac. In: A. B. Ilić and D. Nenadić, eds., Tomislav Gotovac. 1st ed. Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art and Croatian film’s association, pp. 268–277.

Fraser, N. (1990). Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy. Social Text, 25/26, pp. 56–80.

Habermas, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Burgeois Society. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hansen, M. (1993). Foreword. In: O. Negt and A. Kluge, eds., Public Sphere and Experience. Toward an Analysis of Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere. 1st ed. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, pp. IX–XLI.

Hewitt, A. (2005). Social Choreography. Ideology and Dance in Performance and Everyday Movement. 1st ed. Durham; London: Duke University Press.

Jameson, F. (1993). On Negt and Kluge. In: B. Robbins, ed., The Phantom Public Sphere. 1st ed. Mineapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 42–75.

Marjanić, S. (2014). Krontop hrvatskog performansa. 1st ed. Zagreb: Bijeli Val.

Miles, M. (2009). Public Spheres. In: A. Harutyunyan, K. Hörschelmann, M. Miles, eds., Public Spheres After Socialism. 1st ed. Chichago; London: Intellect Books, pp. 133–150.

Negt, O. and Kluge A. (1993). Public Sphere and Experience. Toward an Analysis of Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere. 1st ed. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press.

Pejić, B. (2006). Public Cuts. In: U. Jurman, ed., Sanja Iveković: Public Cuts. 1st ed. Ljubljana: Zavod P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E., pp. 11–34.

Piotrowski, P. (2011). In the Shadow of Yalta. The Avant-Garde in South-East Europe from 1945 to 1989. 1st ed. London: Reaktion Books.

Šuvaković, M. (2003). Art as a Political Machine: Fragments on the Late Socialist and Postsocialist Art of Mitteleuropa and the Balkans. In: A. Erjavec, ed., Postmodernism and the Postsocialist Condition. Politicized Art in Late Socialism. 1st ed. Berkley: University of California Press, pp. 90–135.

Virno, P. (2007). A Grammar of the Multitude. For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).