If we recall Hannah Arendt’s famous statement that power “begins where the public sphere ends” (Arendt 1955, p. 639) and link her words with the generally accepted view that the term “public sphere” is of great importance for the development and the functioning of modern civil societies, it at first seems paradoxical to talk of the public sphere in a state socialist dictatorship like that which had predominated in Poland since the end of the Second World War. In the first years following the end of the war, the mass media had already been gradually organized along the lines of the existing system in the USSR of directed and controlled media and were subject to party control.1 It was their job, among other things, to broker harmony between the rulers and the general public, to extol the successes of the system and to emphasize the satisfaction and the optimism of the citizens of the People’s Republic. At the same time, any information that could even slightly interfere with this image was eliminated (Pepliński 2004, p. 15).2 Any attempts to express dissent in the official mass media were quickly suppressed in these structures. However, this does not mean that only public spheres created by the regime existed. If one understands the public sphere – in state socialist societies as well – not as a monolithic dimension, but instead as a dynamic sphere that allows a multitude of different approaches, one can detect within these regimented structures partial areas of freedom, against which the state certainly took restrictive steps. Examples are illegal publications in the “drugi obieg” (second circulation), pamphlets and performance art, but also strikes and demonstrations which enabled unheard content to be given a hearing in official discourse.

According to Nancy Fraser, these forms of public communication can be called subaltern counter-publics3: Based on their experience that they cannot express their concerns in the ruling public sphere, the protagonists of excluded groups attempt to establish discursive counter-public spaces in order to formulate counter-attitudes and thus to give expression to that which is not heard in the prevalent public sphere. Fraser thus points out that mechanisms of exclusion and the resulting conflicts must be seen as motivation for the creation of public spheres (Fraser 1992).

Thus, as regards the situation in the Polish People’s Republic, one can discern an area of conflict which is reflected in a permanent debate about and negotiation of what can be public and what cannot. I want to address this dynamic in my essay and focus on the historical strike at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk in August 1980. This strike is of considerable importance because the protests in Poland only took on a political dimension with the strike.4 In addition to demanding the reinstatement of the crane driver Anna Walentynowicz, who had been fired shortly beforehand because she campaigned for better working conditions at the shipyard, and demanding pay rises due to rising food prices, those striking in Gdańsk now also made political demands. They drew up twenty-one postulates, which included improvement of working and living conditions, the demand for free and independent unions, and the right to strike and the freedom of expression. Within a few days more and more workers joined the strike in solidarity with the Lenin Shipyard and on 17 August an inter-factory and Poland-wide strike was declared. This collective revolt of the workers and the support for their undertaking by the majority of the population forced the Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza (Polish United Workers’ Party, PZPR) into negotiations with the Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy (Inter-Factory Strike Committee, MKS), which was founded at this time, and ultimately led to the establishment of the trade union Solidarność (Solidarity). Thus, for the first time in the history of real socialism, the ability of opposing groups to negotiate was recognized and a process was initiated that was to gradually bring political change to Poland and other satellite states of the Soviet Union and in 1989 led to peaceful revolution.5

In the following I will therefore investigate how the strikers succeeded – despite the regimented access to mass media – in finding a public sphere for their concerns. In doing so, I will focus on the theatrical dimension of the Gdańsk strike, which I consider to be one of the constitutive strategies, and I will show how this, at first, local public sphere expanded nationally and transnationally.

The sociologists Jürgen Gerhards and Friedhelm Neidhardt have developed a differentiated model of the creation of public spheres, which can be transferred to the creation of counter-publics. They differentiate among three levels of interaction on which public spheres can be constituted (Gerhards and Neidhardt 1991): They consider the most elementary form to be encounters, in which people meet each other on a variety of occasions and communicate with each other, for example, in conversations at work, at the bus stop or in a bar. Encounters on this level occur more or less by chance, are thematically fluctuating and relatively unstructured. The next level is the level of gatherings, which are thematically focused interactions, such as discussion meetings or talks, which are planned by specific organizers (people, groups or organizations); participation in these interactions assumes an interest in the subject. Here, as on the encounter level, interaction takes place between people who are physically present, i.e. the protagonists and the audience are in the same place and can react directly to each other. The number of those taking part in the communication is thus restricted to a specific group of people who are present, meaning that the chance to influence public opinion is relatively small in comparison to communication on the level of the mass media. And it’s this mass media level which Gerhards and Neidhardt state to be the most effective level of the constitution of the public sphere because the technical infrastructure allows it to reach a large audience. Thus, they emphasize: “The subjects and opinions that are articulated on other levels only then also reach the perception of the general public when they are taken up, reported and intensified by the mass media” (Gerhards and Neidhardt 1991, p. 55). Since the audience does not have to be physically present, it becomes more abstract; instead of face-to-face communication, communication conveyed via the media dominates here.

Although all of these three forms of public sphere creation have the inherent potential to articulate dissent, when we consider the process of revolution in Poland it can be seen that here it is precisely the first two levels identified by Gerhards and Neidhardt that played an important role. The encounter level represents the beginning of the process of autonomization and thus the process of creation of a counter-public. Discussions between those in opposition to the government here took place first in private homes, at secret meetings, before they moved on to the next level, the level of public organized events, the gathering level, in the form of protests such as strikes, demonstrations, rallies, etc. If the two sociologists consider protests as a special form of public sphere creation, we can thus state for the Polish case that it was their activation that enabled opposition powers to carve out their own public sphere as an alternative to the official one and thus to receive attention for their concerns and their protest.

What’s special about this level of public sphere creation is the direct and compressed articulation that takes place between people who are physically present. Their specific form of action is direct and collective action in which explicit opinions about a subject can be expressed, whereby a person or a group who were previously not identifiable in a public sphere can consciously and without the aid of mass media achieve visibility with their own voice and their own body. For this reason, this level can be ascribed a theatrical character, because theatrical character consists of the performance potential which is characterized by the fact that an acting person or group deliberately presents itself to others and – in the process – produces signs which it uses to evoke meanings and direct effects.6 This situation can also be observed in the practice of protesting, because those who stand up to express a protest become – in the form of deliberately exhibited actions, which they produce directly using their own body, their own voice and their own creativity, in the eyes of the people that are watching – political subjects and thus protagonists who are consciously acting in front of an audience (Szymanski 2012, p. 23–31; p. 39–51). During the strike in Gdańsk the strikers and their helpers established deliberate actions to inscribe themselves into the public sphere. In the following this aesthetic inscription will therefore be considered in more detail.

The organizers of the strike in Gdańsk sensed from their knowledge of Polish media that their concerns would not find an ear in the state-owned media. At the same time, they also knew from their experience that the reporting – if it took place at all – would be based not on facts, but on news which served the party apparatus and was thus falsified. (Interview with Krzysztof Wyszkowski in March 2009) And they were right. In Trybuna Ludu (People’s Tribune) from 16/17 August 1980 there is only a short comment that there had been walkouts in Gdańsk. One looks in vain in this and the following issues for background information, such as the reason for the strike, the demands, who was behind the strike etc. It was not until the issue dated 20 August that the demands were mentioned briefly and perfunctorily in a single sentence: “The majority of the demands presented concern salary problems, the increasing costs of taking care of family, difficulties concerning day-to-day family life and an inadequate supply of food.” A similar approach to the strike can also be seen in the other mass media, where overall it can be seen that the term “strike” is avoided and instead the term “walkouts” is used.7 It is striking that in all the articles in the mass media there are recurring patterns that refer to hostile powers, which are willing to inflict damage on the Polish People’s Republic, or to large financial losses due to the walkouts. It is suggested again and again that the Polish people are tired of the strikes. For example, in the edition dated 30/31 August, i.e. shortly before the Gdańsk Agreement, Trybuna Ludu printed negative opinions on the walkouts, such as that of a worker from Opole: “We are all longing for a normalization of the situation and an orderly working rhythm in the whole country. The extension of the strike will not lead to any good.” In addition to the presentation of such arguments, the willingness of the government to talk to the strikers and the efforts to respond to the demands of the working class were emphasized.

Thus, in the reporting of the mass media only the voice of the government was heard, only the speeches of the party officials and the opinions dictated from on high were conveyed to the public sphere. The strikers themselves did not get to have their say, their postulates were only reported very perfunctorily and thus the general public was prevented from perceiving them. It is thus understandable that the strikers developed their own strategies to convey their demands to the public; this included establishing various stages and the aesthetic inscription of their demands.

One of the first stages during the strike in Gdańsk was a digger that the initiators of the strike chose as a stage on which to announce the course of the strike to the workers and to select the strike representatives. This stage was also used by the shipyard director, Klemens Gniech, who asked the strikers to return to work and promised them that he would take care of the negotiations between the management and the representatives of the workers. He had almost convinced the majority of them, when “Lech Wałęsa appeared … behind the manager” – as Jerzy Borowczak, a Gdańsk shipyard worker remembers – and said: “Do you still recognize me? I toiled here in the shipyard for ten years and I still feel like a shipyard worker because I have the trust of the workforce. I have now been unemployed for four years.” (Wałęsa 1987, p. 120) Wałęsa, who lost his job as an electrician at the shipyard because of his oppositional behavior, used a megaphone to appeal to the workers gathered there to continue the strike. His appearance on this digger prompted thunderous applause amongst the audience and saved, as Timothy Garton Ash notes, the strike from collapse. (Ash 2002, p. 43)

The digger-stage mentioned here conforms to the spatial arrangement of the classical idea of a stage that we are familiar with from the theatre: a raised place on which the protagonist acts while the audience below him watches. Lech Wałęsa and Klemens Gniech stood on the digger during their discussion and were thus in a raised position. The spectators, the striking workers, surrounded these two protagonists and looked up to them. This type of stage creation using large or high objects can be seen all over the shipyard throughout the whole course of the strike. Thus, not only diggers, but also electric trucks, tables, chairs and even the shoulders of comrades served as stages. Nevertheless, the establishment of these stages only reached a limited public sphere, the public sphere of those who were in front of the particular stage in the shipyard. Thus, for example, Wałęsa’s discussion with Gniech on the digger only reached those people who were on site and who attended the discussion. In order to reach a larger counter-public, to inform the people about the real reasons for the strike and the real demands, and thus to break through the lies of the mass media, it was necessary to use other tactics.

One obvious course would have been to go on a protest march through the town, drawing attention to themselves and using banners and shouted slogans to proclaim the reasons for the strike. However, they decided to dispense with such a course due to bad experiences in the past: On 14 December 1970, there were spontaneous strikes and demonstrations in the coastal towns of Gdańsk, Szczecin, Gdynia and Elblag because of dramatic increases in the price of staple foods. The strikers asked the government in vain to enter into negotiations with them and finally took to the streets of their towns to put pressure on the government. On 16/17 December, the protests escalated and there were bloody skirmishes between the army and militia units and the strikers, in the course of which people died.8 Therefore, leaving the shipyard did not seem an appropriate strategy to the strikers in 1980. It was thus necessary to use a different tactic to conquer the public sphere outside the shipyard. Two types of stage creation can be identified as particularly successful here: One functioned visually and the other, in contrast, aurally.

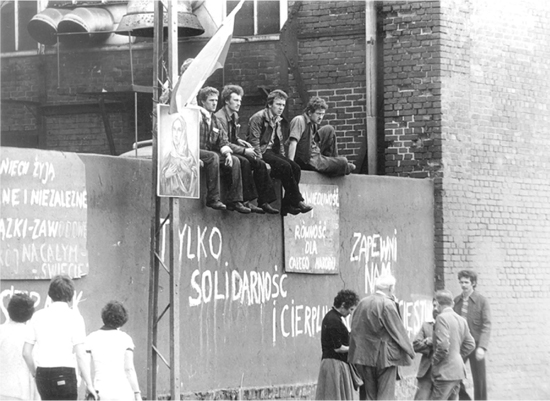

The shipyard compound was separated from the world outside the factory by walls and fences. What was originally constructed as a demarcation element to separate the interior of the workspace from the outside space of the city played a connecting role in the days of the August strike. The walls and fences were used as a stage to make public what was happening inside. They permitted the protagonists to make contact with the outside world using the simplest methods. Thus, for example, the strikers wrote their twenty-one postulates on large boards and fixed them to the outside of the factory walls and fences. In this way, all those passing by the shipyard could learn the aims of the strike, which had been concealed or only perfunctorily reported by the mass media. The journalist Irena Dryll remembers: “I was there when they were hung up. The postulates themselves were on large wooden boards. Young people hung them up … and in such a way that they were visible from afar. It was a moving occasion because everyone could sign their name under the postulates” (Miller 2005, p. 75). As can be seen from this quotation, the boards did not just have an informative function, but were also performative, as per John L. Austin’s definition, because they were capable of prompting actions (Austin 1962). They encouraged passersby to place their signature under the demands, thus demonstrating their support. In this way, a community was also formed by the act of signing and was presented outwards in the form of solidarity. Since the state observed all actions and registered all acts of opposition, it goes without saying that such an action was not without danger. And yet the number of signatures grew daily and with them the publicizing of the postulates. In addition, the strikers also wrote various slogans on the walls, such as “The strike is under way!” (“Strajk trwa!”), “Long live free and independent trade unions and peace all over the world!” (“Niech żyją Wolne i Niezależne Związki Zawodowe i Pokój na całym świecie!”) or “Only with solidarity and patience is our victory guaranteed!” (“Tylko solidarność i cierpliwość zapewni nam zwycięsto!”).9 In this way the strikers were reacting to false reports that they had allegedly ended the strike and also it allowed them to communicate with the world outside the shipyard.

But it was not only pedestrians passing directly by the walls and fences who could be reached by this kind of public sphere creation and obtain information about the strike. Since part of the walls and fences were located near railway tracks, all travelers coming to or leaving Gdańsk could likewise see all this information. In this way, despite the capping of the telephone connections which had been ordered by the party leadership to prevent communication between Gdańsk and other cities, it was possible to convey news about the strike and the postulates of the strikers to train passengers, thus guaranteeing that they were disseminated throughout the whole of Poland. In this way the direct and, initially, local public sphere could be expanded to a national one. This kind of transmission of information proved to be very successful, as the contemporary witness Zenon Kwoka confirms, in particular because by this means other factories outside Tricity10 heard of the events, whereupon they sent delegates to Gdańsk and thus joined those striking there. (Interview with Zenon Kwoka in March 2009) Zbigniew Gach, who was one of the train passengers, describes his view of the situation as the train approached the shipyard:

We approached the Gdańsk Shipyard station. Nearly all the passengers in the train compartment looked towards the shipyard. They craned their necks to soak up every detail. The train was also going slower. On the concrete screen that separated the shipyard from the Polish Navy street, small groups of men with helmets and berets were sitting on the roofs of the shipyard sheds. They gesticulated, waved to the train passengers and made the letter “V” with their fingers. On the walls … there blazed painted slogans: “We are with the people, the people with us, we shipyard workers will not give up! Long live justice!”

(Miller 2005, p. 45f.)

This statement clearly shows that not only the slogans acted as players on the wall and fence stages, but that the strikers themselves also acted on them and on the roofs of shipyard sheds and the walls. Using their bodies and their voices they were able to draw the attention of those outside. In addition to appearances in small groups, individual players also used these stages to communicate with those gathered outside the gates and to inform them in detail about the course of the strike. In this context, we might mention Lech Wałęsa, for example, who – as Krzysztof Wyszkowski points out – displayed a special performative talent during the days of the strike and appeared again and again in different contexts (Interview with Krzysztof Wyszkowski in March 2009). It is evident from the observation logs of the state security service on the strike that Wałęsa, who was recorded here under the pseudonym “Wół” (ox), spoke to those gathered outside the gates several times a day and reported the news about the strike to them. His appearance on 20 August is recorded as follows:

In his short appearance, the supporting actor with the pseudonym “Wół” informed the people that there were around 270 delegates from different factories in the shipyard. And that there was no disagreement within the Inter-Factory Strike Committee. In addition, he issued the information that the delegate conference, in which the delegates would report on the current situation in their factories, would begin at 9 o’clock.

(IPN GD 0046/364 t. 1, k. 111)

It is clear from this report that Wałęsa not only conveyed news about the strike, such as when something would take place or what had taken place, but that he also attempted to correct the lies spread by the mass media, such as the rumor about an alleged dispute within the Committee. In addition, Wałęsa used his appearances to encourage the audience in crisis situations: As when, for example, the strikers and their supporters outside the shipyard no longer believed that victory was possible or when fear of a military attack threatened to break their will, he was able to use song to bring about a reversal. Then he climbed on to the stage – the aforementioned wall, a digger or an electric truck or a table – and began, amplified by a megaphone or a microphone, depending on what he had to hand, to sing a well-known song. Sometimes it was the Polish national anthem, sometimes an old, patriotic hymn, such as God Save Poland. The crowd suddenly quieted down, looked up at Wałęsa, stood up and sang along with him.11 Timothy Garton Ash describes one of Wałęsa’s appearances as follows:

Yet as he sings he is transformed: no longer is he the feisty little electrician in ill-fitting trousers, the sharp talker with many human weaknesses; … now he stands up straight, head thrown back, arms to his sides, strangely rigid and pink in the face, like a wooden figure by one of the naive sculptors from the Land of Dobrzyn where he was born.

(Ash 2002, p. 64)

All these acts increased the general public’s interest in the strike. While at the beginning only a few people came to the shipyard, over the course of the strike the numbers increased, as can be seen in the observation logs of the Polish state security service. The observing officials estimated that there were approximately 150 people at the shipyard on the morning of 15 August (IPN GD 0046/364 t. 1, k. 93); at 10 pm on the same day there were already twice as many (IPN GD 0046/364 t. 1, k. 94). In contrast, during the negotiations with the government representatives, the officials recorded – depending on the day – between 1000 and 3000 people (IPN GD 0046/364 t. 1, k. 117 and k. 139). In particular during the masses held at the shipyard crowds of people streamed to the shipyard to take part and thus to demonstrate their solidarity with the strikers.12 Ewa Juńczyk explains this phenomenon by the fact that going to the shipyard, at that time, represented something like the primary civic duty (Tage der Solidarität 2005, p. 91). And, during those days, this civic duty acquired the name “solidarity”.

In addition to this visual creation of a counter-public using people’s own bodies, a public sphere was also produced with aural means, because the transparency of the events in the shipyard and the resulting opportunity for as many people as possible to participate was important to the leaders of the strike. (Interview with Krzysztof Wyszkowski in March 2009.) This was of particular significance in the negotiations with the representatives of the government. The room that had been selected by the Gdańsk strike leaders for the discussion with the party officials in August 1980 was quite small with space for only a limited number of people. And although it was not in a raised position and did not draw attention by means of any other exposed feature, it acted as a stage.

Its distinctiveness can be described by means of two features: the first of these was visual. The whole wall that separated this room from the lobby was made of glass, and thus permitted all those who were in the lobby to be able to directly see what was happening in the room: Every movement, every facial expression of the participating actors could thus be followed live. Those in the lobby were mainly foreign journalists, but the discussions could be observed not just from the lobby, but also through the few windows of the negotiation room that faced the shipyard compound. Although the windows were very small, they permitted some of the strikers to follow the negotiations visually. Bogusław Turek describes this as follows: “I will never forget the faces of the workers who were glued to the windows of the negotiation room. Exhausted, unshaven and filthy they watched the events, full of hope that it would all turn out in their favor” (Miller 2005, p. 138).

Behind these strikers were hundreds more of their colleagues, and every day more and more people stood outside the gates – all of them also eager to follow the negotiations. It was here that the second characteristic of the room proved to be useful: its connection to the factory’s radio communication system and the microphones that the strikers had finally won the right to have after negotiations with the shipyard manager. Thus, every word that was spoken in the negotiation room could be transmitted live by means of loudspeakers out of the negotiation room, and not just as far as the lobby, but to the whole premises of the Lenin Shipyard, and even beyond the factory gates. Lech Wałęsa observed this as follows:

In one of its first resolutions, the strike committee demanded access to the shipyard’s radio communication system. We knew that it was in our interest to make public all the discussions and negotiations… . The shipyard’s loudspeaker system included all departments and production halls.

(Wałęsa 1987, p. 166)

Thus, everyone who was on the shipyard premises had the chance to be present at the negotiations – to follow the events on the stage, if not visually, then aurally. For this reason, we can speak of a threefold audience for the negotiations: 1. the journalists present in the lobby, 2. the workers on the premises of the shipyard and 3. those who were patiently waiting outside the factory gates. The dialogues, i.e. the speeches and responses of the groups of protagonists involved were followed by the whole audience, as is documented in the film Robotnicy ’80. Here one can see the absolute attention that accompanied the negotiations, the concentrating faces of the workers all over the shipyard who did not want to miss a single word, because what the government negotiators said, any concession that they made, was of great importance to everyone. Thus, we can agree with Wałęsa’s statement that “Our strike took place with the curtains open” (Miller 2005, p. 167). This theatrical strategy ultimately also allowed the strikers to exert pressure on the government, because the transparency of the negotiations, the fact that every resolution could be heard live by a large crowd of people and thus could no longer be retracted, distorted or denied without obviously appearing to be a lie was able to stop the party officials’ tactics of deception – at least for the period of the Gdańsk negotiations at the Lenin Shipyard.

Foreign reporters13 in particular proved to be a valuable support here, enabling the events to be made public across local and national borders. Despite the difficult conditions, because the telecommunications with the town were disrupted and the transmission of their observations to their home countries now and then required a great degree of creativity, they reported to the whole world without the restrictions of censorship and thus, by means of the creation of a transnational public sphere, they were able to help to exert pressure on the Polish government. For example, the reporter for ARD was Peter Gater, who, according to Der Spiegel (The Mirror), provided “German television with strike reports of a rare intensity” (Anon. 1980, p. 99). His uncensored reports and interviews were broadcast by many European and US television stations. While the faces of Lech Wałęsa or Anna Walentynowicz were not well-known in Poland at this time, nearly everyone outside the Iron Curtain knew them (Anon. 1980, p. 99).

In summary, it can be noted that during the Gdańsk strike in August 1980 the public sphere in the People’s Republic of Poland, which was dominated by the Communist regime, was able to be penetrated with the aid of visual and aural stage creation and thus a counter-public could be constituted. In this way, it was possible for the strikers to bring themselves, the reasons for their strike and their demands into the public sphere, to inform their fellow citizens and to expose the deficits in the reporting of the official mass media. This began a process which could expand from a direct and local public sphere to a national one and finally – with the help of foreign journalists – to a transnational public sphere.

1The Central Office for Control of the Press, Publications and Public Events (Główny Urząd Kontroli Prasy, Publikacji i Widowisk, GUKPPiW) was already established in 1946 to censor and homogenize the media landscape. It formulated the directives of the PZPR as guidelines for the sectors, which were under its jurisdiction. In the beginning, the GUKPPiW was primarily responsible for legitimizing the accession to power of the Communist Party; it was later more focused on the field of propaganda (Pepliński 2004, p. 15).

2It should, however, be kept in mind that the performance of the censorship was dependent on the stability of the central organization of the PZPR: In times in which there was unity and stability within the party, the control of the mass media was implemented effectively. In contrast, in times of crisis, the system began to falter (Paczkowski 1997, pp. 33–34).

3Nancy Fraser developed her concept in a critical discussion with the bourgeois conception of public sphere by Jürgen Habermas.

4The first large strikes and demonstrations in Poland took place in 1956; there was further large-scale unrest in 1968, 1970 and 1976. For the history of strikes and demonstrations in Poland, see Paczkowski 2003.

5For more on the upheaval in Poland in 1989 see, for example, Ash 2002; Kühn 1999. A comparative overview is offered by Schelényi and Schelényi 1994.

6For more on the concept of theatricality to which I refer, see e.g. Fischer-Lichte 2004 and Szymanski-Düll 2016.

7This is connected to the fact that, for Marx and Engels, strikes served as a means for the assertion of the working class and its interests in capitalism and were seen as preparation for the emancipation of the working class. In a socialist state, in which emancipation was theoretically available to the worker, it was thus not appropriate for the rulers to speak of a strike because that would mean admitting that there were flaws in the system. For the term “strike” see Lösche 2008, pp. 558–559.

8For more on the unrest in 1970, see, among others, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej 2009; Danowska 2000.

9See the relevant photographs in the illustrated book by Trybek 2000, pp. 40–43.

10Gdańsk, Gdynia and Sopot are called Tricity.

11The songs and their effects are recorded in precise detail in the observation logs of the state security service (IPN Gd 0046/364/1 Sierpień ’80).

12On the theatricality of religious acts and the significance of Catholicism during the Gdańsk strike in August 1980, see Szymanski 2012, pp. 103–155.

13Polish journalists were also present during the strike. However, they were in a difficult situation because their attempts to report on the strike failed due to censorship regulations or targeted technical faults, such as switching off fax machines and telephones. In this context, some of the journalists published a declaration in which they took a stand against the system and distanced themselves from it, revealing its manipulation of the public sphere of the media. The declaration states “We Polish journalists who are present in the Gdańsk coastal region during the strike declare that much of the information printed so far, and especially the commentary, does not correspond to the actual events. This situation promotes disinformation. The current blocking of the telephones and the lack of possibilities to publish material that portrays an accurate picture of the situation are deeply painful to us and do not allow us to properly fulfill our professional obligations” (KARTA 2005, p. 67).

Anon. (1980). Daß ihr da seid. Der Spiegel, 35, pp. 99–101.

Archive Material Institute of National Remembrance, Gdansk: IPN Gd 0046/364.

Arendt, H. (1955). Elemente und Ursprünge totaler Herrschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Europäische Verlagsanstalt.

Ash, T. G. (2002). The Polish Revolution. Solidarity. 2nd ed. London: Yale University Press.

Austin, J. L. (1962). How to Do Things with Words. 1st ed. London: Oxford University Press.

Danowska, B. (2000). Grudzień 1970 roku na Wybrzeżu Gdańskim. Przyczyny, przebieg, reperkusje. Pelpin: Bernardinum.

Fischer-Lichte, E. (2004). Theatralität als kulturelles Modell. In: Erika Fischer-Lichte et al., eds., Theatralität als kulturelles Modell. 1st ed. Tübingen; Basel: Francke, pp. 7–26.

Fraser, N. (1992). Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actual Existing Democracy. In: C. Calhoun, ed., Habermas and the Public Sphere. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA; London: MIT Press, pp. 109–142.

Gerhards, J. and Neidhardt, F. (1991). Strukturen und Funktionen moderner Öffentlichkeit: Fragestellungen und Ansätze. In: S. Müller-Doohm and K. Neumann Braun, eds., Öffentlichkeit Kultur Kommunikation. Beiträge zur Medien und Kommunikationssoziologie. 1st ed. Oldenburg: BIS, pp. 31–89.

Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. (2009) Gdańsk Grudzień ’70. Rekonstrukcja, dokumentacja, walka z pamięcią. 1st ed. Gdańsk: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej.

KARTA. (2005). Tage der Solidarität. 1st ed. Warsaw: KARTA.

Kühn, H. (1999). Das Jahrzehnt der Solidarność. 1st ed. Berlin: BasisDruck.

Lösche, P. (2008). Streik. In: D. Nohlen and F. Grotz, eds., Kleines Lexikon der Politik. 2nd ed. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, pp. 558–559.

Miller, M., ed. (2005). Kto tu wpuścił dziennikarzy. 1st ed. Warsaw: Rosner i Wspólnicy.

Paczkowski, A. (2003). Strajki, bunty, manifestacje jako “polska droga” przez socjalizm. 1st ed. Poznan: Poznanskie Tow. Przyjaciol Nauk.

Pepliński, W. (2004). Censura jako instrument propagandy w PRL. In: P. Semków, ed., Propaganda w PRL. Wybrane problem. 1st ed. Gdańsk: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, pp. 14–21.

Schelényi, I. and Schelényi, B. (1994). Why Socialism Failed: Toward a Theory of System Breakdown – Causes of Disintegration of East European State Socialism. Theory and Society, 23, pp. 211–231.

Szymanski, B. (2012). Theatraler Protest und der Weg Polens zu 1989. Zum Aushandeln von Öffentlichkeit im Jahrzehnt der Solidarność. 1st ed. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Szymanski-Düll, B. (2016). Theatralität als Methode – Eine Perspektive aus der Theaterwissenschaft. In: S. Coelsch-Foisner and T. Heimerdinger, eds., Theatralisierung. 1st ed. Heidelberg: Winter, pp. 53–67.

Trybek, Z. (2000). Oni Tworzyli Solidarność. 1st ed. Gdańsk: Trybek, Chmielecki.

Wałęsa, L. (1987). Ein Weg der Hoffnung. 1st ed. Vienna; Hamburg: Zsolnay.