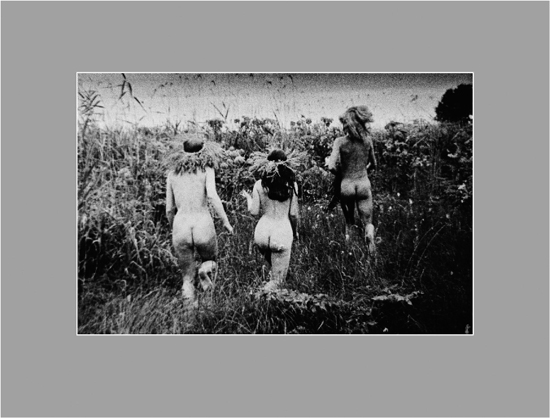

Courtesy: Atis Ieviņš.

In the present article, I will examine performance art in Latvia in the 1970s through the concepts of appropriation and intermediality. I propose that the acts of appropriation resulted, first of all, from the restrictions imposed by the political regime on the upcoming genre of performance art, and, second, from collective actions and participation in joint, hybrid projects. Due to the sociopolitical circumstances, which demanded unconditional conformity to the Soviet regime, performance artists in Latvia operated in a free-thinking community uniting all members in non-hierarchical creative expression and democratic participation. This micro-environment and networking in the cultural periphery ensured certain creative freedom and an opportunity to avoid the internalization of Soviet values best illustrated with two synthetic, ideological constructions – the New Soviet Man and the Homo Sovieticus. This interpretative framework is to be supported with two case studies, the event-based art projects of Andris Grinbergs (b. 1946) and those of Imants Lancmanis (b. 1941) organized in the second public sphere.

The word “appropriation” derives from the Latin appropriare meaning “to make one’s own”. In the arts, appropriation can be unconscious and is almost inevitable, because “almost all artists engage in some sort of appropriation in that they borrow ideas, motifs, plots, technical devices, and so forth from other artists” (Young 2008, p. 4). Appropriation can also be deliberate, because artists can intentionally borrow, copy or alter pre-existing images and objects. A number of artists were intending to question the nature or definition of art itself, as well as rebel against “the modernist notion of originality and its taboo on imitation” (Ambrose et al. 2012, p. 179).

In the 1970s, the agency to re-contextualise an existing artwork, this way giving it a new meaning, was especially pursued by American artists such as Richard Prince, Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger and Jeff Koons – their artwork was even termed appropriation art. In this context, appropriation as a gesture of copying and quoting deconstructs the notion of the original, emanates a sense of déjà vu and is considered a postmodern practice (Krauss 1986, p. 19). The appropriation artists in the West were influenced by several pivotal theoretical texts: the 1934 essay by the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, the 1967 essay by the French theorist Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author”, as well as the 1985 book The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths by the American art critic Rosalind Krauss. The ideas expressed in these texts supported the argument “that there was no such thing as authorship and originality, only unoriginal, endless copying” (Kuspit 2011, p. 240). Consequently, deliberate borrowing and copying were the artistic tools in the West to address such issues as agency, power, creativity and the myth of origin.

However, the appropriation in art in Soviet Latvia in the 1970s was different from the one in the West, and performance art has an especially rich history of the occasions when the works of art or their motives migrated from one author or medium to another. Yet, although the act of borrowing was deliberate, this choice was not rooted in postmodern critical thinking. Rather, the acts of appropriation resulted, first of all, from the restrictions imposed by the political regime on performance art. In a system of ideological commitment and strict art hierarchies, only “traditional” art disciplines, such as painting and sculpture, were considered politically correct and serious, suitable to serve the ideological purpose of the Soviet ideologues. According to Latvian art historian Vilnis Vējš, the Soviet system discriminated against not only specific individuals but entire artistic forms by denying them the status of a professional art or ranking them low in the cultural hierarchy (2010, p. 25). Performance art belonged to these genres and, consequently, existed as a hybrid “in-between” of diverse media, such as photographs, silkscreen prints,1 and paintings. This intermediality was a result of a process of change that performance art underwent in order to adapt to external political factors. All these media were not mere forms of documentation, but intermedia – a “combinatory structure of syntactical elements that [came] from more than one medium but [were] combined into one and [were] thereby transformed into a new entity” (Ox 2011, p. 47). They existed in parallel, echoing and reemploying each other, hybridizing and growing “into forms that [became] effective and convincing media in their own right” (Friedman 2005, p. 61).

Appropriation in Soviet Latvia occurred as a result of community actions and participation in joint, hybrid projects. Due to the sociopolitical circumstances, which demanded unconditional conformity to the social system, artists in Latvia sought ways to escape the political indoctrination and apathy resulting from the suppression of creative agency. A freethinking community consisting of close acquaintances, friends, and family members was one of the solutions. This micro-environment ensured that through networking in the cultural periphery it was possible to implement certain creative freedoms and avoid the ideological pressure and censorship – and thus to be innovative, inventive, spontaneous and experimental. Performance art particularly attracted many creative individuals of diverse and interdisciplinary backgrounds – fashion designers, theatre actors, film students, painters, writers, poets, musicians, photographers, etc. The process of generating performance was often implemented as “collaborative creation” (Heddon and Milling 2006), uniting all members in non-hierarchical creative expression and democratic participation – something that the political regime undermined. Among these circles of friends, the issues of authorship were not perceived as the violation of copyright; it was the possibility for alternative, autonomous and uncensored action that mattered most.2

A useful theoretical framework to examine Latvian performance art against the choices that the artists had made to create a pseudo-reality, where they did not need to conform to the Soviet ideals, were the synthetic constructions of the New Soviet Man and Homo Sovieticus. These ideological conceptions epitomized the contradictions that performance artists in Latvia had to cope with in every sphere of life: education, work, personal relationships, lifestyle, etc. In the first public sphere, one was expected to be a patriotic Soviet citizen conforming to the ideology and the regime. It implied that one could not obtain information from the sources published in the West, not be engaged in the discipline of performance art or to take photographs of the streets in broad daylight or of naked people in groups. Latvian artists could not dress too provocatively and they could not have any other form of relationship but heterosexual. These and other restrictions of basic human rights and freedoms were crucial reasons why performance artists created a second public sphere, where they sought means and ways to escape repressions, indoctrination and homogenization and to implement their creative agency. From this perspective, performance artists were failures of the Soviet ideologues, because Soviet values were never internalized and the Latvian performance artists never took on the roles of a Homo Sovieticus.

As indicated by Russian sociologist Lev Gudkov, “the concept ‘New Man’ or ‘Soviet Man’ appeared in the 1920s and 1930s as a postromantic version of the subject of historical changes” (2008, p. 13). The socialist society had to be built as an optimistic, classless society by the new human species – Homo Sovieticus. This new man was a significant model for mass orientations and identities. He was the carrier of certain values, qualities, and properties, and, accordingly, of a better future. The Soviet ideologues postulated that the man of the future should place the social and public interest first, and should share the aims and principles of the communist ideology by demonstrating his willingness to sacrifice himself for the sake of “the future of the country,” “the Motherland,” “the Party,” and “the people”. In 1932, Maxim Gorky wrote:

A new type of person is being created in the Soviet Union, his character traits can be determined with no doubt … He feels himself as the creator of the new world, his goals depend on his mind and willpower, and therefore he has no reason for pessimism. He is young not only in terms of his biological age, but also historically. He is a power that has just realized his path [of life], his historical significance. He … is led by a simple and clear doctrine.

(Gorky 1953, p. 289)

In Latvia, too, this ideological plan was implemented, first from 1940 to 1941 and, later, from the end of World War II through the years of the Soviet occupation until 1991, when state independence was restored. As noted by Latvian art historian Elita Ansone, socialism and communism were dogmatic systems with their own mythology based on the hierarchy of signs and symbols, for which, similarly to religion, it was very difficult to find affirmation in real life, therefore literature, cinematography and fine arts were regarded as ideal tools to make the Soviet myths, among them the one concerning a new type of individual, seem believable, fascinating and inspirational (2008, pp. 6–8). The new human type, the positive hero, that the Soviet system was supposed to produce as a result of indoctrination, collectivization, repression and social control had to be healthy, athletic, heterosexual, optimistic, selfless, diligent and patriotic (having a Soviet, rather than a national identity). An article entitled “The New Soviet Man” published in the daily newspaper in Latvia in 1940 praised the New Soviet Man, stating that “conscientiousness, cordiality, excitement and modesty are the main traits that characterize the young Soviet patriots. From their perspective, domesticity, work and heroism are firmly and clearly defined. Each person is included in the collective of all Soviet nations” (Anon. 1940, p. 4). The positive hero was also propagandized by socialist realism in fine arts, leaving behind numerous portraits of cultural workers, excellent labourers, war veterans, athletes, militiamen and representatives of other professions in public service (Ansone 2009, p. 74).

However, it must be noted that the construction of Homo Sovieticus has not remained constant throughout the period reaching from the 1920s until today. Gudkov writes that the first attempts to provide evidence of the empirical – rather than the ideological – existence of the individual of a fundamentally different type than the ideologues postulated appeared at the end of the 1950s (2008, p. 14). Other interpretations followed in the 1970s and the 1980s, offering parodies or transfigurations of the idea of Soviet Man. Important studies on the existence of the Soviet Man as a sociological phenomenon were carried out in the late 1980s under the supervision of Russian sociologist and political scientist Iurii Levada (2003). This contemporary perspective provides a more critical approach to examine the (de)construction of the Homo Sovieticus.

According to Gudkov, Levada, and other contemporary Russian researchers, the Soviet system did shape a new category of human being, but this new human type was not a strong and convincing role model. On the contrary, it possessed the following features: he was a mass, very average type, someone who had passively adapted to the existing social order by lowering the threshold or his level of needs and demands; the Homo Sovieticus was the “ordinary” man with (intellectual, ethical and symbolic) limitations, who knew no other models and ways of life, because he had to live under conditions of an isolated and repressed society (Gudkov 2010, p. 61). The Homo Sovieticus was not allowed to differ, show initiative, or strive for innovation – he was morally and intellectually paralyzed. According to Gudkov, he did not exercise any control over ruling authority or his own leadership, he was a “supervised man” – supervised by the ruling authorities on all levels of life (ibid., p. 52).

To avoid the adaptation to such a grim model of existence and social reality requiring homogenization, collectivization and intellectual paralysis, artists and creative individuals in Soviet Latvia of the 1970s invented their own “survival strategies”. These personalities intended to escape the regulated atmosphere of Soviet(ized) life, even with the minor gestures of adapting to fashion and having a provocative look, or gatherings in cafes. They established their own micro-environment, immersed in alternative reality (a second public sphere) created out of books, film, music and philosophical conversations: “Reading saved us from the dull reality behind the doors of Kaza,3 [from] the Soviet everyday life – fight for peace, meetings of trade unions, festive demonstrations of May 1st and the October Revolution” (Zvirgzdiņš 2004, n.p.).

Such gatherings, communication and socializing within the community of family, friends or subculture (e.g. hippies) established networks, often leading to nonconformist art activities in the cultural periphery. One example is the Office Group (Biroja grupa, 1971–1974), which was an interdisciplinary artists’ collective founded by the graduates of the National Film Actors Studio.4 The Group did not have any institutional status, formal membership or structural hierarchy. Art, film and theatre enthusiasts with various backgrounds gathered three times a week in an informal atmosphere to collaboratively stage improvisational scenes aiming for alternative and experimental techniques in theatre, mostly focusing on performing without any verbal communication. The corporeal activities were accompanied by poetry readings, painting, discussions on art and semiotics,5 as well as shared passion for Antonioni films. The group had only one public performance – a ritual-like mini-drama without any text or words – at the students’ gathering of the Tartu University in November 1971.6

In the genealogy of performance art in Latvia, the Office Group stands out as one of the first artistic attempts to create a hybrid, interdisciplinary project, where creative individuals from various backgrounds could cooperate to generate a performance as collaborative creation. The element of improvisation and spontaneity was crucial in order to experiment with the narrative structure and acting techniques, whereas the non-hierarchical networking and the notion of democratic participation offered an alternative space for implementing one’s creative agency and practicing the freedom of non-regulated decisions. The Group is also important because it appropriated motives and patterns from various visual arts disciplines and theatre, as well as supporting the idea that there were no strict categories among these trajectories. Consequently, such an approach resonated with the idea of intermediality proposed by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins, who in 1966 described intermedia as art that falls “between media” and proposed that the separation of artistic media into rigid categories is “absolutely irrelevant” (2003, p. 38). To Higgins the happening was the ultimate “intermedium”, “an uncharted land that lies between collage, music and the theater” (ibid., p. 42).

The Office Group was also a very influential and crucial factor in the career of Grinbergs as a performance artist, because it inspired and encouraged him to work in an interdisciplinary direction, exploring the trajectories of alternative lifestyle and broadening the traditional boundaries of arts. It was during the Office Group period (August 1972) when his first happening The Wedding of Jesus Christ (Jēzus Kristus kāzas) took place.7 Grinbergs, his wife, friends and photographers went to Carnikava Beach where they engaged in an improvised wedding ritual that lasted for two days. There were a lot of organisational and preparatory works before the happening, as attested by various props such as antique crockery, wine, candles, a metal bed, as well as costumes and various accessories such as crowns of roses and necklaces of rowans made in advance.

The title The Wedding of Jesus Christ was borrowed or appropriated from the famous rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar (1973) that Grinbergs managed to watch before it was being prohibited in Latvia. According to Grinbergs, the title did not have any religious implications, because he was against religion, considering it to be a violation of self-determined human spirit – the iconic figure of Christ served as a mere decoration (Grinbergs cited in Kļaviņa 2011, p. 255). As American art historian Mark Allen Svede points out, the act of appropriation was manifested in the allegorical application of the religious figure. The denigration of the symbolic value could possibly be, on the one hand, decoded as blasphemous in the Christian context, and on the other hand, as anti-ideological in atheist contexts: “The Wedding of Jesus Christ was successful on a number of levels: religion turned into a modern aesthetic spectacle … and religion was made apocryphal through joyful eroticization” (Svede 1994, n.p.). Moreover, this performance and the resulting accompanying images also place Grinbergs in the history of mediatized performance art, since the image of Christ was appropriated as early as 1898, when American photographer Fred Holland Day presented himself as Christ in a photographed performance The Seven Words. Such games of representation within the photographic medium acknowledge the symbiotic relationship between photography and performance resulting in intermediality, as well as emphasizing the subversion, re-invention and innovation that are integral components of appropriation in the artistic discourse.

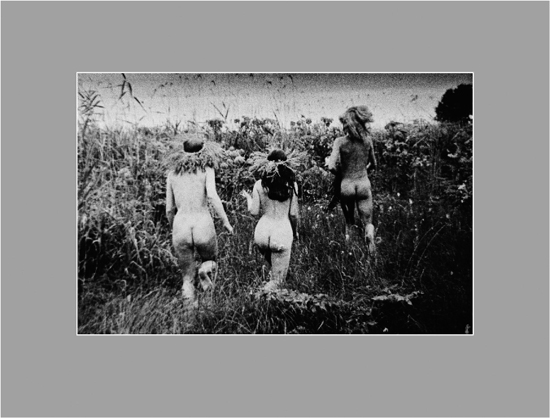

Courtesy: Atis Ieviņš.

Furthermore, it was not only the figure of Christ perceived as anti-ideological in the Soviet context. Nudity, a self-evident norm and a form of liberation in all happenings of Grinbergs, was a prominent element of creation, too, since the totalitarian body of Homo Sovieticus needed to be freed from all restrictions and ideological burdens. To the artist the body was “the only zone of freedom” (Grinbergs cited in Kļaviņa 2011, p. 257). Nudity, inspired by the hippie movement’s alternative lifestyle, was also a form of protest against prevailing puritanical attitudes: “Sexual revolution … was a protest against the system. If you didn’t belong to yourself, all your thoughts were regulated, and the only [thing] that you had was your body – with it you could do anything you wanted” (Grinbergs cited in Landorfa 1999, pp. 22–23). Consequently, the combination of collective actions involving “indecent”, irrational behaviour and nudity, explorations of shifting and changing identity in hybrid non-ideological projects, as well as references to the Bible and Western culture was something that could only be implemented in the second public sphere – uncontrolled by the KGB’s panoptic sight and uninhabited by the Homo Sovieticus.

To Grinbergs the body-focused anthropocentric art eventually became an instrument to explore his own identity, especially in terms of sexuality, which was always floating between heterosexual, homosexual and bisexual trajectories. With this liminal identity – a state of in-between-ness and ambiguity – Grinbergs risked violating the criteria of Homo Sovieticus. Therefore, his performance venues had to be transferred to a depoliticized space distanced from the Soviet reality: on Carnikava beach, in Mazirbe boat junkyard, in his own apartment. These geographically and culturally peripheral locations were partly necessary to avoid legal repercussions, because in the Latvian SSR homosexuality was criminalized, with a penalty of up to five years in prison. Moreover, the power structures could use the evidence of homosexuality to force the respective individuals to cooperate with the Council of Ministers of the Latvian SSR’s Committee for State Security (the KGB) (Lipša 2017).

Since Grinbergs was married,8 had a son and worked as an arts teacher for children with learning difficulties, he probably did not cause any suspicions in terms of his open sexual orientation. However, it can be questioned whether the legitimate form of kinship associated with a heterosexual marriage was for Grinbergs not a form of gender performance, in order to adapt to the homophobic Soviet rule.9 This phenomenon of double life is well characterized by the artist himself: “Of course, I have often thought that the entire life is a theatre and all that we get depends on how good we play our roles. Where is that place one can be real? This double life continues endlessly” (Grinbergs cited in Meistere 1992, p. 2). Thus, it can be suggested that for Grinbergs the second public sphere provided a certain asylum, which allowed him to avoid the distortion of his personality and identity, or even to prevent legal consequences and imprisonment for not meeting the discriminatory ideals of the Homo Sovieticus. Performance art provided time and space, where Grinbergs could feel “authentic” and “autonomous” as an artist. He has repeatedly emphasised that he has always preferred the life of an outsider as opposed to being part of the Soviet art system, creating commissioned and conformist artwork and exhibiting it in the official museum or gallery space. This strategy also helped him to avoid the internalization of Soviet values, which were epitomised by the ideological construction of Homo Sovieticus.

Another example of intermediality and appropriation that resulted in a collaborative performance project involved the artist Imants Lancmanis, his family and friends. Lancmanis was a graduate of the Department of Painting at the State Art Academy of the Latvian SSR. In 1972 he began to work as a Deputy Director of the Rundāle Palace, a baroque palace built in 1736 and suffering serious damage in 1919 during the Latvian War of Independence, as well as through the Soviet period. The restoration of the venue became the lifetime project and passion of Lancmanis. However, the palace was not only a place of work, it was also a playground to implement immersive site-specific and “total” art10 projects, where experimental and carnivalesque collaborative creations could be organised.

Between 1971 and 1984 Lancmanis and his friends organised 12 themed balls and carnivals, devoted to different topics, such as the Roman Empire, Rococo period, the UFO, the 1905 Revolution, etc. These events required that different motives and styles were appropriated either from a certain culture, aesthetics or historical events and personae. The fact that even historically accurate crockery was made to ensure as authentic aesthetic experience as possible illustrates that the slightest detail was carefully calculated in these balls. Being a combination of so many mutually related elements, these process-based events were properly choreographed multimedial works of art, hybrid environments with staged ceremonies and rituals, costumes, props, scenography, lighting, and music, which were aimed at entangling spectators in multi-sensory experiences and creating a surreal, alternative reality made as a stark contrast to the dull and obedient world of Homo Sovieticus.

By creating such a large-scale interdisciplinary and site-specific work involving research and preparation as well as improvisation, Lancmanis performatively re-invented and de-contextualized an architectural structure:

Rundāle interested me as an opportunity to “re-create” a world which no longer exists, actually this is what I wish to do in my paintings as well: to conjure up a world that either is no longer there or has never existed, except in my mind; to make it so tangible and detailed that people would believe such a world could exist. Rundāle gives you a chance to “re-create” the palace, the environment and park in total; every room you enter takes you to a different era. That’s what I like about Rundāle – the huge installation that it has become. That is indeed the right word. It is a large, but very consistent and conceptually directed installation. That is at the foundation of what I like about it, that people say that Rundāle is a living palace.

(Lancmanis cited in Lindenbauma 2011, pp. 176–177)

As a director of an institution, Lancmanis was responsible for the restoration works of the Palace, but as an artist, he used the site as environment to create a parallel world, where, by wearing masks and costumes of different historical personae and periods, he, his family and friends could, paradoxically, drop the masks of Homo Sovieticus. Grinbergs had a very similar approach: “I dressed my models and created an environment, where they could express themselves and which could to some degree ‘rip’ them out of their masks, turn them into live human beings, containing more than you see on an everyday basis” (Grinbergs cited in Meistere 1992, p. 2). It shows that the regime was unable to paralyze artistic agency, and that through the art in the second public sphere the artists sought ways to pursue autonomous, uncensored action on the fringes of the official culture. In doing so, both artists, unknowingly and intuitively, displayed the main features of performance art: the body of the artist as the material, form and content interplay, blurred boundaries between art and life, experiential immediacy and the dematerialization of the artwork, prevalence of process and human subject over product, as well as the presentational modes of action in real time over representational, commodified objects.

As regards the definitions of appropriation, Iain Boyd Whyte’s interpretation of appropriation from the perspective of translation theory offers a useful approach to the phenomenon, even in the arts:

Translation can be interlingual – from one language to another; intermedial – from one medium to another; and intercultural – from one culture to another. In every case, when the object signified moves across language, medium, or culture, original meanings and restraints are loosened or shed entirely and the motif is emancipated, allowing it to take on whatever role it might fancy in the new context.

(Ambrose et al. 2012, p. 185)

Intermedial appropriation is the feature that characterizes performance art in Latvia in the late Soviet period, too. Not only did artists appropriate different motifs and styles based on aesthetics, but performance art itself underwent a process of change and turned into a hybrid consisting of different media in order to emerge in the first public sphere – although in “camouflaged” forms, such as exhibition catalogues, book covers, photographs, paintings or interior design objects. The character of intermedia can be seen in the case of Grinbergs, who always had his performances documented via photography. Among the participants in his artistic actions there were always professional photographers, capturing events with snapshot-like aesthetics. For Grinbergs, photography was the most essential medium in his performance: “How did I start making those photos? They are my unrealized paintings. I could not draw, write or express myself well enough in music, yet I had ideas” (Grinbergs cited in Meistere 1992, p. 2) that needed to take shape in an experimental, uncommon form.

Grinbergs’s performances were mostly photographed by Jānis Kreicbergs, who was a well-known fashion photographer in the first public sphere. When off-duty, Kreicbergs often joined Grinbergs and together they created a hybrid work of art, which transformed from a process-based, one-time action into a fine art object becoming easily transportable and adaptable. Kreicbergs appropriated the plots, characters and aesthetics from Grinbergs’s happenings and presented the resulting images as a new and original work of art. He did so because he never considered himself only a photographer invited to document the process-based events under a strict guidance of an authoritarian director. Instead, Kreicbergs saw performances as a collaborative project with an element of spontaneity and improvisation. They provided him with an opportunity to produce free creative expression. Similar acts of appropriation occurred in the case of photographer Atis Ieviņš, who experimented with merging painting and photography. This way he produced several silkscreen prints by appropriating Grinbergs’s performances – the outcome was presented as serigraphy. Whereas the wedding of Lancmanis was appropriated by a prominent Latvian painter Maija Tabaka, who created the large-scale painting Wedding at Rundāle (Kāzas Rundālē, 1974), based on a photograph of Lancmanis’s wedding.11 These and other instances of performance art and its parallel (inter)media, which occurred as a result of hybridization and adaptation, illustrate that intermediality and appropriation were integral parts of performance art in Latvia allowing it to migrate from one author and medium to another, also crossing the boundaries between the first and the second public sphere.

Figure 10.2 Cave Paintings (Alu zīmējumi), 1973/1974, Atis Ieviņš’ Private Archive.

Courtesy: Atis Ieviņš.

The democratic attitude of building a community and practicing sexual freedom, both important features of the Latvian art of the second public sphere, were contrary to the image of the ideal socialist individual, or Homo Sovieticus. The positive hero of the Soviet ideology was expected to demonstrate obedience, trust in the superior authorities, discipline, and responsiveness to the commands of the regime. These values were needed to ensure the continuity of the totalitarian regime:

The qualities of the positive hero could be best explained in terms of the requirements of a totalitarian society, which desires to maximize control over its citizens. Patriotism and Party-mindedness, antiindividualism, … acceptance of subordination, unquestioning loyalty to leaders, lack of genuine initiative, obedience, adaptability, susceptibility to shame – all these are qualities, which facilitate control over the individual.

(Hollander 1983, p. 49)

However, performance artists proved the opposite: the regime was unable to silence their creative expression, individualism and initiative, and, consequently, they never turned into Homo Sovieticus.

Intermediality and appropriation in performance art in Latvia in the late socialist period were not only important counter-cultural side effects of ruling sociopolitical circumstances, but also the results of individual efforts to establish a community and micro-environment where democratic principles of freedom of expression, participation, initiative and non-hierarchical work relationships could be implemented. Performance art adapted to the given social reality by hybridizing into different media and managing to appear in the first public sphere in a “camouflaged” form, that is in photographs, paintings and printed canvases. This process of metamorphosis and intermedial appropriation demonstrated the unique symbiotic relationship between a process-based art and a fine art object without presupposing the superiority, authenticity, originality or authority of either mode. Such joint collaborative projects and networking in the second public sphere ensured that the artists could express their creative agency while remaining immune to the ideological pressure, indoctrination and homogenization epitomized by the synthetic constructions of the New Soviet Man and the Homo Sovieticus.

1Silkscreening is a printing technique that allows printing images repeatedly on a single canvas. The machine-like look and the lack of artist’s touch was especially appealing to Andy Warhol, who produced most of his iconic works in this technique.

2It is interesting to note that pantomime – which is akin to performance art in that it is body-based and process-based – could exist officially and, in fact, was very popular all over the USSR. It was praised by the Soviet ideologues as a kind of Soviet Esperanto – a language, which all Soviet brotherly nations could understand without words.

3The most famous cafe in Riga in the 1970s, a meeting place for the Soviet counter-culture.

4The National Film Actors Studio was established in 1965. Research on the Office Group has been carried out by Latvian art historian Vilnis Vējš, available on CD-ROM, the Contemporary Art Centre of Latvia.

5Lectures given in 1969 by the Tartu University professor Yuri Lotman.

6The most important legacy of the Group would have been the experimental “self-portrait” short films made in 1972. Unfortunately, through an incident with the Committee for State Security (KGB) only two of these films survived. Due to the previous records of Andris Grinbergs’s activities, in January 1974, the KGB started to show interest in the Group’s activities: Ivars Skanstiņš received a notice to come to the KGB office for an interrogation, Juris Civjans’s film was “borrowed” and never returned. In fear of repression, Mudīte Gaiševska cut out “compromising” shots from her film, and Eižens Valpēters’s film was mysteriously lost, while he was working as a renovator at the Rundāle Palace. In January 1974, the Office Group ceased its activities and gatherings.

7Participants: Andris Bergmanis, Irēna Birmbauma, Māra Brašmane, Ināra Eglīte, Mudīte Gaiševska, Aija Grinberga, Andris Grinbergs, Inta Jaunzema (Grinberga), Ninuce Kaupuža, Ingvars Leitis, Ināra Podkalne, Sandrs Rīga, Ivars Skanstiņš, Eižens Valpēters.

8His wife Inta Grinberga was a frequent participant in Grinbergs’ performances.

9Grinbergs talks openly about his sexuality and queerness only in the interviews after 1992, when homosexuality was decriminalized in Latvia.

10The idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk – that is, a total artwork – was prophetically envisioned by Richard Wagner as the integration of traditional disciplines into a unified work with the aim of intensifying the audience’s experiences of art.

11This painting was also crucial in Tabaka’s own development as an artist, since it was “the beginning of [her] art theatre, system of images and autonomy that was referred to as the Theatre Of Madame Tabaka” (original emphasis; Blaua 2010, p. 85).

Ambrose, K. et al. (2012). Appropriation: Back Then, In Between, and Today. The Art Bulletin. 94(2), pp. 166–186. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/23268310 (Accessed June 13, 2017).

Anon. (1940). Jaunais padomju cilvēks. Jaunais Komunārs, 103, p. 4.

Ansone, E., ed. (2009). Padomjzemes mitoloģija: Muzeja raksti 1. 1st ed. Riga: Latvijas Nacionālais mākslas muzejs.

Blaua, L. (2010). Maija Tabaka. Spēle ar dzīvi. Riga: Jumava.

Friedman, K. (2005). Intermedia: Four Histories, Three Directions, Two Futures. In: H. Breder and K. Busse, eds., Intermedia: Enacting the Liminal. 1st ed. Dortmund: Schriften zur Kunst, pp. 51–61.

Gorky, M. (1953). O starom i novom cheloveke. In: M. Gorky, Sobranie sochinenii. 1st ed. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo khudozhestvennoi literatury, p. 289.

Gudkov, L. (2008). “Soviet Man” in the Sociology of Iurii Levada. Sociological Research, 47(6), pp. 6–28.

Gudkov, L. (2010). Conditions Necessary for the Reproduction of “Soviet Man”. Sociological Research, 49(6), pp. 50–99.

Heddon, D. and Milling, J. (2006). Devising Performance. 1st ed. Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Higgins, D. (2003). Intermedia. In: L. Moren, ed., Intermedia: The Dick Higgins Collection at UMBC. 1st ed. Baltimore: University of Maryland, pp. 38–42.

Hollander, P. (1983). The Many Faces of Socialism: Comparative Sociology and Politics. 1st ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Kļaviņa, A. (2011). Andris Grinbergs [interview]. In: H. Demakova, ed., The Self. Personal Journeys to Contemporary Art: The 1960s – 80s in Soviet Latvia. 1st ed. Riga: Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Latvia, pp. 246–263.

Krauss, R. E. (1986). The Originality of the Avant-Garde. In: R. E. Krauss, ed., The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, pp. 1–41.

Kuspit, D. (2011). Some Thoughts About the Significance of Postmodern Appropriation Art. In: R. Brilliant and D. Kinney, eds., Reuse Value. Spolia and Appropriation in Art and Architecture from Constantine to Sherrie Levine. 1st ed. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 237–250.

Landorfa, S. (1999). Dzīve ir tik garšīga! [interview with Andris Grinbergs]. Privātā dzīve, 30(2), pp. 22–23.

Levada, I. A. (2003). Homo Post-Sovieticus. Russian Social Science Review, 44(1), pp. 32–67.

Lindenbauma, L. (2011). Interview with Imants Lancmanis. In: H. Demakova, ed., The Self. Personal Journeys to Contemporary Art: The 1960s – 80s in Soviet Latvia. 1st ed. Riga: Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Latvia, pp. 164–181.

Lipša, I. (2017). Homosexuals and Suppression Mechanisms in the Latvian SSR: The Context of the Soviet Baltic Republics (the 1960s–1980s). Latvijas Vēstures Institūta Žurnāls, 2(103).

Meistere, U. (1992). Interview [with Andris Grinbergs]. Atmoda atpūtai, 3, p. 2.

Ox, J. (2011). Intersenses/Intermedia: A Theoretical Perspective. Leonardo, 34(1), pp. 47–48.

Svede, M. A. (1994). Hippies, Happenings and Homoeroticism: Latvian Performance Art’s Opening Act [Available at the Dodge Collection Archive at the Zimmerli Museum, New Brunswick, USA].

Vējš, V. (2010). Performing Arts. In: V. Vējš, ed., And Others. Movements, Explorations and Artists in Latvia 1960–1984. 1st ed. Riga: Contemporary Art Centre, p. 25.

Young, J. O. (2008). Cultural Appropriation and the Arts. 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

Zvirgzdiņš, J. (2004). Par “Kazu”. Studija. Available at: www.studija.lv/?parent=1479 (Accessed April 28, 2016).