Figure 11.1 Milan Knížák, Stone Ceremony, 1971.

Courtesy: Milan Knížák.

The Czechoslovakian performance artists who fought for the autonomy of their art and consequently rejected the dominant doctrines of socialist realism and aesthetic conformism were forced to present their works and actions in the second public sphere: in private apartments, ateliers or basements. Today, these art actions are often only available in the form of rudimentary instructions; or they have been preserved for posterity by a single camera, the only witness, as it were.1 In what follows, however, I will discuss art actions and experiments that were performed in deserted natural landscapes, often far away from the cities. In Eastern Europe, many neo-avant-garde artists chose to set up their studios in nature. Equipped with a photographic camera and a few props, they set out into the mountains, visited open fields or went to the sea, where they could work without being disturbed. By making nature, a sphere not fully appropriated by society, the preferred site of their performances, they contributed to a certain blurring of the lines between land art and performance art. In the Western theory and practice, these two genres have been kept apart and are usually discussed as discrete categories in the aesthetics of neo-avant-garde art. Their respective representatives developed different ways of opposing the traditional rules of presenting and exhibiting their artworks. In the East European context, the art critic Elisabeth Jappe talks about a kind of “media nomadism” (1993, p. 67), by which she means a certain mixing of genres, such as action art, land art, concept art, and performance art. As I will try to demonstrate in the following pages, the artistic endeavours of this geo-cultural region defy categorization according to genre-specific characteristics.

One of the remarkable things about these performances in nature is that they evoke traditional motifs of melancholy. By withdrawing from the everyday world and its automatisms, all movements that encourage an escape into nature bare the traces of a politics of the subject that we can describe as melancholic. Thus, the politics of melancholy does not imply an intervention in the concrete political issues of the day. Instead, and paradoxically, it means a kind of dissociation from these issues and from the horizon of expectations created by the state-socialist directives concerning artistic representation and the ideological commitment of the artist. Accordingly, the attachment to nature, which already in the ancient theory of the temperaments (Hippokrates 1936) was defined as a melancholic state of being that creates a kinship with the element of the Earth, indicates a disengagement from social ties, which, as Seneca pointed out, turns out to be a necessarily futile attempt.2 Seneca’s argument that an escape into nature by no means constitutes a return to an ideal state of being will be taken up in the following performance analyses. As we will see, the aesthetic and political dimensions of these performances are closely intertwined with the ideological and social circumstances of their time.3

This melancholic penchant for a sphere that lies outside of the city and culture is best exemplified by an action that was performed collectively, Milan Knízak’s Stone Ceremony (Kamenný obřad, 1971). Accompanied by a group of artists, Knízak turned to the theme of isolation. Every participant built a small circle made out of stones around himself or herself, only to stand still, silent, eyes looking down at the floor.

The melancholic mood of the performance was not simply the effect of an image of people being spatially separated from each other and not engaging in any form of communication. In addition to carrying a literal political message about the exclusion of the non-conformist artist, the deserted landscape, a remote, desolate, isolated scenery of ruins, also brought to mind allegories of vanitas and the futility of the world.4 Quite strikingly, the barren landscape corresponds to a medieval topos of melancholy, namely that of acedia. When actualizing the code of human helplessness in the face of the motionless stagnation of the glaring sun devoid of all signs, Knízak was very much aware of this cultural tradition.

According to the medieval imagination, when humans find themselves out in the daylight and in a natural environment that lacks all movement or rhythm, they are at the risk of being affected by acedia, since, realizing the “inescapable stagnation of all things” (Bader 1990, p. 11), they become world-weary and, despite their intentions to the contrary, are simply unable to get up and do things. “Typically, acedia arises between 10 am and 2 pm, in full daylight”, that is to say, “it is not so much the sun itself but its idleness or apparent idleness that gives rise to acedia. It is a disturbance of rhythm, the disappearance of a rhythmic order as such” (ibid.). Acedia, which is also known as the noonday demon, led the medieval monk to stare into space and was considered a danger that threatens to bring inaction and thus a deadly sin, for it beguiled people into gaping at the motionless sun and surrendering to an existential boredom. This type of unproductive distraction, which made the monks abandon the reading and prayers, threatened to make people neglect their own environment and lose interest in the world.

The deserted landscape, with its constant, unchanging and rhythmless atmosphere, was considered particularly dangerous for the medieval melancholy. Thus, it is not the night but the sun-drenched midday landscape that threatens to lure people into inactivity, as the preacher Qoheleth says: “I have seen all the things that are done under the sun; all of them are meaningless, a chasing after the wind” (Goebel 2003, p. 449).5 The fact that, since the late Middle Ages, the accidious state of mind became detached from its religious context and was consequently removed from the catalogue of vices is largely due to Petrarch’s semantic re-evaluation of acedia, which paved the way for an amalgamation of accidious and melancholic discourses that continued into modernity, and which at the same time provides a link to Milan Knízak’s Stone Ceremony. This fascination with the sun and its stagnation returns in a number of Eastern European landscape actions highlighting the political significance of the topos: as Petrarch pointed out, when people are seized by the monotony of nature, they experience a sweet world-weariness that can be turned into creativity (ibid. pp. 460–462), whose efficiency, however, can only be recognized beyond the social realm.

From the perspective of conceptual history, acedia and melancholy acquire overlapping meanings in Walter Benjmain’s analysis of the baroque tragic hero,6 or, according to Adorno (1991) and Heidegger (Theunissen I996, pp. 28–29), become coextensive in modernity. They are characterized by the slowing down of time, which becomes duration and opens up a sphere in which there is freedom not to act or to dissent, and not in the framework of so-called leisure time, which is regulated and spent in accordance with the norms established by society. So, instead of the religious ideas related to medieval faith, Knízak’s accidious landscape of bodies negotiates the experience of tiredness, the lack of variation, and “the unreadability of the world” (ibid., p. 15) which, as Dave MacQuarrie has shown (2012), are anxieties of modern and contemporary culture. In Stone Ceremony, we are confronted with an image of reluctance, which, as we will see, keeps oscillating between an apolitical attitude and subversion.

Due to the unreadability of the world and the experience of melancholy it gives rise to, in these remote natural landscapes Knízak can focus on himself and the regularities inherent in the state of nature. Losing oneself in the observation of nature is the point of many of Milan Maur’s performances, such as the ones in which he threw himself in a river to be taken by its currents or followed the whimsical flutter of butterflies and then charted these random paths of movement. On 9 May 1988, about one and a half decades after Knízak’s Stone Ceremony and twenty years after the Prague Spring, he decided to follow the sun, from sunrise till nightfall, in an effort to get closer to it (On May 9, 1988 I walked from dawn to dusk, following the sun [9. května 1988 šel od úsvitu do soumraku za sluncem]). The route, which has been marked on a map, documents Maur’s daily choreography that led the artist from the city into the countryside and forced him to ignore the streets and pathways and their predetermined courses of movement. Submission to nature and its rules and using the sun not only as the source of light but also as the primary organizer of artistic statements are precisely what the performative experiments collected in this chapter have in common. They draw inspiration from a cosmic monotony in order to overcome social constraints.

When a group of Slovakian action artists decided to set up their easels in nature, as it were, this was a result of concrete political events that had happened in that country (Bátorová 2009, pp. 21–50). The decisions made at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party in 1956 led to a relaxation of restrictions in the cultural sphere of Slovakia, and even artists who emancipated themselves from socialist realism were allowed to exhibit their works freely. After the Prague Spring, however, this liberal cultural politics changed and neo-avant-garde artists were marginalized. As art historian Zuzana Bartošová argues, the artists of the 1970s should not be described as “alternative” but rather as “unofficial”, given the cultural political circumstances of the period (2005, p. 5). Due to the new conditions of production in the country, they were only able to present their work in front of a limited audience. Against this backdrop, withdrawing into nature was for many artists a “solution for realizing projects of intimate nature, which were later made available to the public through various forms of documentation” (Bátorová 2009, pp. 100–101).

Intrigued by the possibilities of the artistic exploration of nature, Michal Kern decided to spend several years on observing and aesthetically capturing the processes of a landscape in a close-up with no perspective. The Slovakian artist grew up close to nature and, after completing his studies in painting, the surrounding landscape served as his only atelier. Equipped with a white canvas or a mirror, he would go and search for images in the middle of the Slovakian forest, trying to reproduce the fragmentary reflection of shadows of a sunny landscape on the two-dimensional surface or to capture it in a calculated photographic moment. In Searching a Shadow (Hl’adanie tieňa) from 1980, we see the cast shadow of a bough captured as a temporary trace on a white canvas positioned horizontally in the grass. What the viewer is presented with is a double framing of a snippet of nature, which, on the one hand, by means of the sunlight, temporarily inscribes itself on an apparently randomly placed white surface while, on the other hand, being exposed to a light-sensitive photographic emulsion as an artificially highlighted fragment of nature.

While the monochrome play of reflexes keeps disappearing without a trace as soon as the sun retreats, and thus the medium of classical representation remains blank and infinitely reusable, Kern’s photographs capture the fleeting encounters between light and surface, artistic framework and state of nature.7 What is remarkable about this procedure is the double application of the photographic principle, which underlines the media-reflexive dimension of Kern’s photographic performances.

As is well known, the first commercial photo album, published in 150 copies, was created in 1846 by Henry Fox Talbot, whose minimal definition of photography as the “Pencil of Nature” foregrounds the physical recording of traces, which is a result of the inscription of light on a two-dimensional surface. In the foreword to his album, Talbot points out that the principle of the mechanical reproduction of images goes hand in hand with the artist’s diminishing power to shape the artwork: the plates are “wholly executed by the new art of Photogenic Drawing, without any aid whatever from the artist’s pencil” (Talbot 1844, p. 89). In this sense, Talbot absolutizes the phenomenon of natural light, which, as technology became more and more prevalent in the arts and the sciences, and the camera obscura, the magic lantern or photography became ever more common, developed into an essential, generative constitutive element of the indexical production of images.

When Kern sets out to visit sunny, dreary landscapes where, after finding refuge from the noonday sun under the trees, he exposes his canvases to nature’s uncontrollable play of lights, he gives up his status as homo generator and limits his artistic control to the selection of the photographic moments that freeze the unpredictable shadow formations. His attitude can be seen in relation to the accidious disposition; his chosen setting is nature at midday and he condenses its monotony through two-dimensional framings. In the melancholic setting, in which artistic control reaches its limits, Kern captures traces of shadows in accidental pictures that seem rather unspectacular. Thus, he subscribes to an aesthetic of chance, the history of which begins with Lucretius’s didactic poem De Rerum natura and is equally represented by Andrea Mantena’s cloud pictures, Marcel Duchamp’s Stoppages and John Cage’s musical compositions.8 These artists are connected by the intention to give up their position as the autonomous creator, to lose their artistic control and thus to explore a production principle that lies beyond artistic will.

In the photographic performance Double Reflection (Dvojité zrkadlenie, 1978), this artistic programme is radicalized. In it, Kern even gave up control over the exact placing of his “canvas”. First, he noticed potential images on the reflecting surface of a lake and placed a square mirror on it. Losing the control over the spatial determination of the floating reflection surface, Kern’s photography framed a picture in the picture that mirrors nature in nature, linking the sky and the water and relating them to each other. Despite the seemingly unspectacular reflections, Kern’s struggle to find a motif is led by an urgent conceptual question that concerns the classical definition of the image as such and helps to overcome it. According to the art historian Horst Bredekamp, who even to this day insists on a definition of the image formulated by the 15th century artist and mathematician Leon Battista Alberti, “we can speak of an image (simulacrum) once the objects of nature, such as a root system, show the slightest traces of human processing. As soon as a natural formation shows signs of human interference, it fulfils the definition of the image” (Bredekamp 2010, p. 34). In accordance with this definition, Kern rejects the idea that the visual arts are inherently concerned with human artefacts and dismisses the concept of the original artist as a genius who creates art out of himself. At the same time, however, through the individual photographic documents, he does produce artworks that provide access to his critical and short-lived art practice.

The simultaneous subversion and intensification of aesthetic framings returns in other land art projects of the period, which, while taking place in the absence of an audience, acquired the status of an artwork due to their documentation. Thus, the photographic performances that take place in nature show the paradoxes inherent in the melancholic politics of representation in which the fading of artistic intention turns out to be an intentional act and which reflects the boundaries of the creative will in art. They demonstrate that the melancholic withdrawal of the self is an ambivalent gesture because this melancholic disposition does not entail a disappearance, it only entails a turning away. The melancholic politics of representation that the Czechoslovakian performance artists espouse relativizes the status of a strong “subject” as homo generator or homo politicus (Steinlein 2003, p. 156), but at the same time makes clear that these artists do not withdraw completely, they express their absence in society, they leave traces behind, disrupt the aesthetic consensus, and critically subvert the ideas of social functionality and efficiency.

The Slovakian land art and performance artist Ľubomír Ďurček, who also performed his actions all by himself and made them accessible to the public only by means of photographic recording, pursued similar artistic aims. Intrigued by the possibilities of transposing nature’s regularities onto the white surface of the picture, in 1984 he delved into the dilemma of putting on paper the horizon, a natural phenomenon that is impalpable, untouchable and can only be perceived from a distance. It is for good reason that the horizon as a supposed mark of a distant contact surface between the sky and the earth or the water is a recurring motif in utopias. It suggests that there is a place where the mundane and the ethereal touch each other, which de facto does not exist.9 By letting one half of a white sheet of paper submerge under water and then photographing the half-wet paper, Ďurček was trying to capture on a piece of paper that point of the horizon where “the water” and “the white sky” converge, and to represent the unbridgeable gap between them literally, through the principle of indexicality: his paper is divided by a clear line separating the dry upper part and the lower half which had been deformed into a wavelike shape. The photographic idea is manifest in Horizon as well, but instead of the light, it is the water that inscribes itself on the surface.

The action Horizon (Horizont, 1984) provides a lucid demonstration of the extent to which the genres of performance art, land art, painting, photography and concept art have been woven together in Kern’s und Ďurček’s work and aesthetically unified in their artistic practice. The unifying force was the intention to overcome the powerful tradition of representation and to create a direct connection with the thing represented.10 In brief, without aggressively testing the limits of cultural censorship and explaining their withdrawal from society in the sphere of figural representation, which is necessarily shaped by ideological factors, they combined their practices of isolation with moments of the photographic “theatricalization” of nature. These forms of articulation are apolitical only at first sight. For the melancholic gestures have a critical dimension: the oppressed artists find spaces that cannot be censored, places where they are free to become productive and communicate in unusual ways.

From today’s perspective, the action artists who set up their studios in nature can be seen as related to the institutional critique that appeared in the United States at the same time. Artists such as Michael Heizer, Dennis Oppenheim or Robert Smithson left their galleries mainly because they felt that the traditional exhibition spaces were framing their aesthetic interests in a limiting way, which paved the way for land art (Sayre 1989, pp. 211–245). The so-called white cube – that is the white, quadrangular gallery space – reminded them of the rigid structures of the square frame that they also associated with the canvas. Therefore, they sought to expand the possibilities of exhibiting their art by abandoning the regime of two-dimensionality and the tradition of hanging pictures vertically on walls, and adopted a three-dimensional and spatially unrestricted field of compositional possibilities. For them the gallery was a hermetically closed white frame. As the concept artist Brian O’Doherty argues,

a gallery is constructed along laws as rigorous as those for building a medieval church. The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off. Walls are painted white. The ceiling becomes the source of light… . The art is free, as the saying used to go, “to take on its own life.” … Modernism’s transposition of perception from life to formal values is complete. This, of course, is one of modernism’s fatal diseases.

(O’Doherty 1976, p. 25)

Against the backdrop of the restrictions that the museum imposes on art and which to a large extent predetermine and, according to O’Doherty, delimit the possibilities of both the exhibition and the reception of art, the land art artists discovered nature as an “open space” but without any idyllic projections or idealization of the countryside. We can see that their efforts had a lot in common with the Eastern European actions performed outdoors. While embracing nature, neither the “Western” nor the “Eastern” artists had any romanticizing projections or idyllic hopes of a return to a pre-social, paradisiacal primal state. But unlike North American land art, Knížák’s, Kern’s or Ďurček’s actions in nature are not only concerned with showing the restrictive character of the white gallery as an exhibition space or critiquing the art market, but also, and to a larger extent, with the possibilities of presenting art in its political environment. To put it simply, while the abandonment of their ateliers corresponds to the Western aesthetic trends of land art, it cannot be discussed separately from the conditions of production in Eastern Europe and their ideological context.

After having made unusual use of the canvas as a temporary reflection surface beyond artistic fixation, in Touch (Dotyk, 1982) Michal Kern searched for opportunities to create a connection with nature. In it, we see him touching the surface of the water, generating many concentric circles of waves and thus blurring the horizontal reflection of the surrounding scenery of the forest. This gesture of touching epitomizes the minimality of Kern’s connections with the natural landscape, which at the same time uncover revealing asymmetries. The touch does not promise the restoration of a lost unity with nature, but makes us aware of an insurmountable separation which subverts the romantic illusion of a harmonious bodily contact: “Indeed, contact does not carry out any fusion or any identification, nor even any immediate contiguity. Once more we have to dissociate touch from what common sense and philosophical sense are forever according it, namely, immediacy – as evidence itself, as the first axiom of a phenomenology of touch” (Derrida 2005, p. 119). As we contemplate Kern’s minimal intervention in the water surface that produces waves that spread out in space and have uncontrollable consequences, we realize that his touch creates differences instead of fusions, diffuse fields of force instead of harmonious congruence. In this sense, the movement of his hand approaching the water surface reflects Rousseau’s idea about the lost relationship between man and nature and thus the fictional character of the idyllic state of nature which, according to Rousseau, “no longer exists, which perhaps never existed, which probably never will exist” (1964, p. 91). While the photography suggests that the countryside is beyond social construction and control, the aestheticization and artistic articulation of nature imply a distortion. Consequently, nature cannot be shown in its own autonomous reality.

The performance photography Traces in the Sand (Stopy v piesku, 1976) shows a similarly ephemeral intervention in nature, and renders concrete the dilemma of the underground artist, which at the time was understood metaphorically, in a literal form: how is it possible to leave traces outside the official public sphere? Kern leaves a footprint that will soon be erased by rain and wind, but which is captured photographically and preserved as a tiny modification of the environment or a microscopic land art action, as it were.

No matter how lasting or fleeting Kern’s footprints were, we should remember that in the Eastern Bloc the artistic interventions in the natural landscape were rarely motivated by ecological considerations. Since the reports about the continued deterioration of air and water quality were not published behind the Iron Curtain and industrialization was portrayed as a process with only positive consequences, the ecological disaster would rarely become the subject of artistic reflection (Fowkes 2015, pp. 16–19). Instead, these artists were fascinated by nature as a place of work and material for their artistic endeavours, and, in accordance with Alberti’s definition of the image, tried to make minimal changes to nature and its laws.

The impetus to make minimal changes to nature was at the core of the work of the Czech performance artist Jiří Kovanda. In xxx. I carry some water from the river in my cupped hands and release it a few meters downriver. . . (xxx. Vodu z reky prenáším v dlaních o nekolik metru dál po proudu …, 1977), an absurd direction is carried out in all seriousness. Kovanda set an unachievable goal for himself. By trying to accelerate the river’s flow speed, he aimed to intervene in a natural process. He took some water in his hands, ran downstream and then threw a few drops of water back in the river. The image of obsessive work whose result is continually delayed leading to failure is an explicit allusion not only to the mythical figure of Sisyphus, but also to the unnecessary and irrational production directives of the socialist planned economy in which human work was measured by the visible (and often wasteful) effort rather than by efficiency. This motivic superimposition of socialist work and the Sisyphus myth became a leitmotif in the entire Eastern Bloc (Seidensticker and Wessels 2001), but above all in the GDR. In literature and performance art, Sisyphus, who was too smart for his own good and is condemned to forever rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, only to have it fall back in the valley again, was a symbol of the worker who had to devote himself to the realization of the communist utopia and suppress the melancholic certainty of its impossibility.

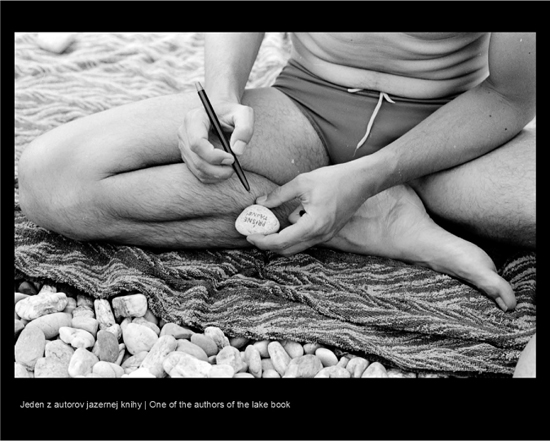

In the August of 1978, excited by the idea of a microscopic intervention in the state of nature, a group of Slovakian artists11 went to a nature reserve south of Bratislava, where they first documented some improvisations, like spraying water or throwing stones about, and then wrote on the stones that were lying about with a pen, writing the book of nature, as it were. The title of the action (Lake Book [Jazerá kniha]) evokes an Augustinian idea from late antiquity according to which nature has become a secret code that awaits decipherment. The assumption about a book of nature that speaks in secret signs is an explicit reference in this collective performance. But contrary to the history of the motif, which includes the Romantic tradition, this art action is not about reading the “book of nature”, but about helping to write and develop it. Thus, nature is not regarded as some untouched primal state, but as a reciprocal relationship between man and landscape. The collective work on the book of the lakescape manifests the intention to overcome the melancholic experience of the “world’s unreadability”, that is to reach an “anti-accidious” (Bader 1990, p. 61) state. In the discursive history of melancholy, reading and writing are considered remedies, even if these intellectual activities lead to a dialectic of creative will and the experience of its boundaries, and thus inevitably change into a melancholic experience. For both reading and writing lead to the disillusionment of the melancholiac, so much so that “all readability can only be seen against the background of much vaster unreadability” (ibid., p. 64).

For some artists, the excitement of these actions derived also from challenging nature’s unreadability and showing its capacity for storing history. To conclude this overview of the politics of melancholy espoused by performance artists who tried to render their withdrawal from everyday life visible through microscopic or ephemeral traces, I would like to briefly consider the actions of Prague artist Zorka Ságlová, who turned Czechoslovakian fields into massive tableaux of memory, highlighting the historical resonances and stratifications of the landscape. Ságlová created temporary monuments to individual episodes from the history of her homeland. Homage to Gustav Oberman (Pocta Gustavu Obermanovi, 1970) took place in the nature reserve Bransoudov, halfway between Prague and Brno. Ságlová used the snowscape as a venue for representing the historical war ruins of her country, which has been occupied and set ablaze many times.12 The action consisted in filling twenty-one bags with petrol, arranging them in a circular pattern and, with the help of friends, setting them alight after sunset. Full of connotations of destruction and a revolutionary new beginning, the powerful light effects evoked a “monumental and fascinating” (Jindřich Chalupecký cited in Fowkes 2015, p. 205) landscape of ruins, which reminded the viewer of a concrete historical event. On the one hand, Ságlová made a reference to the legend of Gustav Oberman, a shoemaker who, during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, kept running up and down the mountainside spitting fire as a sign of his resistance and would not stop even when the soldiers were about to attack him. And on the other hand, Ságlová’s tableau of flames evoked a more recent occupation of the country in the wake of the crushing of the Prague Spring and a series of self-immolation protests that followed the occupation. These are echoes of history, which in Ságlová’s action were coupled with a melancholic feeling caused by the fact that one was not allowed to relate to one’s own history. For the action was centred around the image of a cemetery of unburied victims, which brought into focus those secret but not completely erasable “ruins” that, according to Jean Claire, prevent us from coming to terms with the past. A landscape of ruins is not a residue of the past. It haunts the order of the present and manifests a “never-ending grief at a world lost forever” (Clair 2006, p. 352). Thus, Ságlová’s monument to remembrance can be related to many episodes from the history of global destruction, such as the burning of Berlin or Moscow, London or Dresden, which, performed in nature, can be commemorated in a short-lived monument to history.13 Ságlová historicizes the landscape and shows its hidden scars, and thus creates a space for reflection beyond the time regime of a modernistic, and above all real socialist, emphasis on the present. The field at night, suddenly lit up by the blazing flames, expresses the melancholy of the flight from the present and leads Ságlová into the complex temporal dimensions of the past. These temporal dimensions cannot be precisely identified, but they extend beyond the present, lying “between elsewhere and elsewhen” (Goebel 2003, p. 480).

Courtesy: Ľubomír Ďurček.

In light of these analyses, the escape movements that sought liberation from the consolidated patterns of behaviour imposed by urban civilization can be understood as an attempt to enter a sphere that is neither idyllic, nor a place for creating a parallel society, but which can be used for alternative forms of communication, historical recollections, and aesthetic experiments. The melancholy of monotonous landscapes, be it in sunlight or at night, together with their well-known scenery lacking in variation and the temporary connections or discursive interactions with elements of nature range from illegible writing on stones to an eerie tableau of flames in the twilight dusk. The natural landscape emerges as a protected domain of the second public sphere, which is beyond the control of state surveillance and allows artists to take a step back from day-to-day politics. In it, the neo-avant-gardists of Eastern Europe found a place for a temporary escape and a departure, for a halt and a new beginning.

1In this respect, the photographic performances that did not take place in front of a live audience can be seen as related to what Philip Auslander calls “theatrical modes of performance documentation” (Auslander 2012).

2Seneca’s verdict in his Letter 104 underlines this futility: “tecum sunt quae fugis [you have to fly]” (Seneca cited in Goebel 2003, p. 456).

3In Czechoslovakia, just as in all neighbouring countries, the establishment of a totalitarian system of government was accompanied by a number of repressive measures such as the disempowerment of individuals, the nationalization of their properties, and the restriction of the freedom of speech. After Stalin’s death, the political supremacy of the party remained intact in all spheres of life. These circumstances as well as the decades of supply shortages and economic difficulties led to the events of the Prague Spring in 1968, which was an attempt at democratization “from below”. However, after the troops of the Warsaw Pact had marched in and radical changes in the party leadership had been implemented, it became clear that “socialism with a human face” and liberal values, which had been proclaimed in this country, would have to remain a utopia. The Prague Spring was a real watershed that separated a hopeful period of democratization from the subsequent period of depression and scepticism. This periodization is reflected in the performative arts: Milan Knížák, the most important representative of the first generation of Czechoslovakian performance art, showed a great interest in playful actions in the streets or in factory halls, which, like the American happenings, celebrated the emergence of an egalitarian society “outside of” society and aimed at a temporal escape from the existing orders of sociability. After 1968, the aesthetics of Czechoslovakian performance art changed radically. After the bloody showdown of the Prague Spring and a series of public self-immolations, which started with the suicide of the philosophy student Jan Palach in Wenceslas Square on 19 January 1969, performance artists such as Petr Štembera or Jan Mlčoch made self-harm the central strategy for expressing their melancholic politics of isolation. In basements and other secret private spaces, they carried out auto-aggressive actions, which can be seen as the sedimentation of their failed attempts at establishing connection with the outside world in their own body. Correspondingly, we see an increased number of performances carried out in nature and thus beyond the scope of what was allowed.

4On the tradition of melancholic landscapes and their conventional motifs see Schmidt 1994, pp. 111–114.

5English translation from the New International Version of the Bible.

6“In the inert mass [of the stone] there is a reference to the genuinely theological conception of the melancholic, which is to be found in one of the seven deadly sins. This is acedia, dullness of the heart, or sloth“ (Benjamin 2003, p. 134).

7Maja Fowkes also emphasizes this logic behind the performances in nature: “Whether they found their expression in performance, public art, land art, or conceptual projects, their works bore the characteristics of the concurrent tendency to dematerialize the art object, and therefore left no material or physical remains of their activities in the natural environment, but ensured their presence in art history through photographic documentation and archival materials“ (2015, p. 264).

8Cf. Horst Bredekamp: “Die Wiederkehr des état d’imaginaire. Sammeln aus der Perspektive des Gottesblicks“, talk given at the conference Die Zukunft der Wissensspeicher: Forschen, Sammeln und Vermitteln im 21. Jahrhundert at the Nordrhein-Westfälischen Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Künste (Düsseldorf, March 5–6, 2015).

9For a discussion of horizon as a utopian motif see Koschorke 1990.

10Kern und Ďurček share this fascination with indexicality with a number of American neo-avant-garde artists. Cf. Krauss 1977.

11It was a collaboration among Peter Bartoš, Ľubomír Ďurček, Stano Filko, Vladimír Havrilla and Juraj Mihálik. Cf. Daniel Grúň: “Performative Exhibitions and Artists’ Communities in the 1970s and ’80 in (Czecho)Slovakia”, talk given at the conference Performing Arts in the Second Public Sphere, Berlin, Mai 9–11, 2014.

12For an extensive description of the action see Fowkes 2015, pp. 205–206.

13The main motif in Ságlová’s Laying Out Napkins near Sudomer (Kladení plín u Sudoměře, 1970), an homage to the Czech Hussite Wars, arose from a similar politics of memory. This time, Ságlová visited a field north of Prague to re-enact a legendary battle at its original scene. The Hussites, as the legend has it, laid textile napkins on the field, so that the horses of the occupiers would get entangled in them and the soldiers fall off the horses. Allegedly, this ploy helped the Hussites to victory.

Adorno, Th. W. (1991). Free Time. In: Th. W. Adorno, ed., The Culture Industry. Selected Essays on Mass Culture. 1st ed. London; New York: Routledge, p. 155.

Auslander, P. (2012). The Performativity of Performance Documentation. In: A. Jones and A. Heathfield, eds., Perform, Repeat, Record. Live Art in History. 1st ed. Bristol; Chicago: Intellect, pp. 47–58.

Bader, G. (1990). Melancholie und Metapher. Eine Skizze. 1st ed. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Bartošová, Z. (2005). Neoficiálna slovenská výtvarná scéna sedemdesiatych a osemdesiatych rokov 20. Storočia [dissertation manuscript submitted at Univerzita Palackého, Olomouc].

Benjamin, W. (2003). The Origin of German Tragic Drama. 1st ed. London; New York: Verso.

Bredekamp, H. (2010). Theorie des Bildakts. Frankfurter Adorno-Vorlesungen 2007. 1st ed. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Clair, J. (2006). Die Melancholie der Ruinen. In: J. Clair, ed., Melancholie. Genie und Wahnsinn in der Kunst. 1st ed. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, pp. 350–353.

Derrida, J. (2005). On Touching – Jean-Luc Nancy. 1st ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Euringer-Bátorová, A. (2009). Aktionskunst in der Slowakei in den 1960er Jahren. Aktionen von Alex Mlynárčik. 1st ed. Berlin: LIT.

Fowkes, M. (2015). The Green Bloc. Neo-avant-garde Art and Ecology Under Socialism. Budapest; New York: CEU Press.

Goebel, E. (2003). Schwermut/Melancholie. In: K. Barck et al., eds., Ästhetische Grundbegriffe. Historisches Wörterbuch, Vol. 5. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Metzler, pp. 446–486.

Hippokrates v. K. (1936). Die Natur des Menschen. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Hippokrates.

Jappe, E. (1993). Performance – Ritual – Prozeß. Handbuch der Aktionskunst in Europa. 1st ed. Munich; New York: Prestel.

Koschorke, A. (1990). Die Geschichte des Horizonts. Grenze und Grenzüberschreitung in literarischen Lanschaftsbildern. 1st ed. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Krauss, R. (1977). Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America. Part 2. October, 4(3), pp. 58–67.

MacQuarrie, D. (2012). Acedia: The Darkness Within (and the Darkness of Climate Change). 1st ed. Bloomington: AuthorHouse.

O’Doherty, B. (1976). Inside the White Cube. Artforum, 14(7), pp. 24–30.

Rousseau, J.-J. (1964). The First and Second Dialogues. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Sayre, H. M. (1989). The Object of Performance. The American Avant-Garde Since 1970. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schmidt, H. (1994). Melancholie und Landschaft. Die psychotische und ästhetische Struktur der Naturschilderungen in Georg Büchners “Lenz”. 1st ed. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Seidensticker, B. and Wessels, A., eds. (2001). Mythos Sisyphos. Texte von Homer bis Günter Kunert. 1st ed. Leipzig: Reclam.

Steinlein, R. (2003). Ästhetizismus und Männlichkeitskrise. Hugo von Hofmannsthal und die Wiener Moderne. In: C. Benthien and I. Stephan, eds., Männlichkeit als Maskerade. Kulturelle Inszenierungen vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. 1st ed. Cologne: Böhlau, pp. 154–177.

Talbot, W. H. F. (1844). The Pencil of Nature. 1st ed. London: Longman.

Theunissen, M. (1996). Vorentwürfe von Moderne. Antike Melancholie und die Acedia des Mittelalters. 1st ed. Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter.