Photo: Marinela Koželj.

In her distinguished political memoir, How We Survived Communism and Even Laughed (1993), the Croatian feminist writer Slavenka Drakulić remarked about her experience of Yugoslav state socialism: “In a totalitarian society, one has to relate to the power directly; there is no escape… . politics never becomes abstract. It remains a palpable, brutal force directing every aspect of our lives… . Like a disease, a plague, an epidemic, it doesn’t spare anybody.” Drakulić then followed her metaphor of viral state socialism with a more optimistic decree: “Paradoxically, this is precisely how a totalitarian state produces its enemies: politicized citizens” (1993, p. 17). My contribution to this edition will argue that artists from former Yugoslavia, especially those associated with the New Artistic Practices in the Republics of Croatia and Serbia during the 1970s and 1980s embodied just such enemies for the ways in which they critiqued socialist ideology, attesting to Drakulić’s observation: “To be yourself, to cultivate individualism, to perceive yourself as an individual in a mass society is dangerous. You might become living proof that the system is failing” (ibid., p. 26).

Such living proof was the very matrix of the second (or alternative) public sphere, the topic of this anthology, in which artists were tolerated in Yugoslavia, and which was, as I argue, dependent on the very decisions they made. Deliberating on the notion of “decision,” or choice, as central to the conceptualization and execution of resistance to the state, I focus on the ways in which Yugoslavian artists made art in variegated forms and with subtle modes of ethical commitment and engagement in their time and circumstances. East European art is usually analysed with regards to state repression, and my text is no exception. However, I also approach that authoritarian domination in the context of the artists’ aesthetic determinations, and argue that the emphasis on gender politics and sexuality in conceptual and performance art is to be understood as a mode of opposition.

Like their international colleagues, artists in Yugoslavia were driven to protests by the 1968 “revolt” that philosopher and literary critic Julia Kristeva described as “a violent desire to rake over the norms that govern the private as well as the public, the intimate as well as the social, a desire to come up with new, perpetually contestable configurations” (2002, p. 12). In Yugoslavia such contestable configurations could be understood as a representing of a second public sphere that would be determined by the private albeit political decisions and actions of artists situated within the public. How did these artists’ performance and conceptual works challenge the division between the intimate and the social in Yugoslavia’s brand of socialism? It will be my argument that the artists selected for this essay were interested in raising the intimate sphere – such as confronting gender and sexual norms – to the level of the social and political. By focusing on questions of gender and sexuality in my analysis, I argue that these artists’ experimentation with their own and others’ bodies embodied political acts, as if making a solemn pledge to Walter Benjamin’s decree: “We must wake up from the world of our parents,” (1991, p. 1214)1 or perhaps, “We must stop sleeping in the beds of our parents.”

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s theorization of the multitude negotiates the contemporary possibilities for resistance and the revival of the commons, which they define as “the incarnation, the production, and the liberation of the multitude” (2000, p. 303). The question of decision-making lies at the centre of their argument for such a possibility. They consider decision-making an “act of love,” a “decision to create a new race or, rather, a new humanity” (2004, p. 356), a race that may emerge from “the ontological and social process of productive labor.” Furthermore, they argue, such decision “is an institutional form that develops a common content; it is a deployment of force that defends the historical progression of emancipation and liberation; it is, in short, an act of love” (ibid., p. 351). Anticipating such a view, in “Is It Useless to Revolt?,” Michel Foucault noted already in 1979 that revolt “is how subjectivity … is brought into history, breathing life into it” (1999, p. 134). He further observed in a comment on the question of taking a stand on the Iranian revolution, that it was “a simple choice, but a difficult work” (ibid.). I will argue that such simple choices had the effect of opening up a semi-autonomous sphere, where Kristeva’s “contestable configurations” were possible and probable.

Some may consider my conviction that such decision-making-as-art-in-life is too idealistic, no longer possible, retrograde, or even naïve, especially in light of postmodern theories of undecidability, the death of the author, and the concomitant death of biography, as well as the post–World War II Marxist emphasis on ideology as shaping every aspect of life. The more contemporary regard for the positive aspects of socialism can also be problematic, itself linked to the growing view that state socialism was “not that bad after all.” This latter emotional assessment feeds the resurgence of Marxism in light of the contemporary invasion of privacy, vast repression of student revolts, abject poverty, governmental and corporate corruption, racism and gender inequalities, and media control perpetrated by various iterations of capitalist democracies. Nevertheless, and paradoxically, we live in a time when the very term “resistance” has gained currency in contemporary art, and where the upsurging global biennials regularly include calls for projects that critique social conditions locally and internationally. Thus, the question of what function art can play in addressing repressive politics could not be more acute, and it is especially poignant that many examples throughout this volume come from three to five decades ago and from Eastern and Central Europe.

The artist whose work perhaps best encompasses Kristeva’s “contestable configurations” was Raša Todosijević, who was a leading figure of the Group of Six artists in Belgrade’s Student Cultural Centre (SKC). The SKC in Belgrade became internationally renowned almost immediately after its founding for the conceptual installations and performance actions presented there. Tito founded the SKC in 1968. As a former leader of the Yugoslav Partisans during World War II, a group considered Europe’s most effective anti-Nazi resistance movement, Tito led the country from 1945 until 1980, becoming Yugoslavia’s first President, a dictator known widely as the most benevolent of the East European autocrats. The founding of the SKC took place during what has been termed his “soft dictatorship,” and many interpreted his support of the SKC as a manipulative way to tame the frustrated 1968 counter-culture, especially given that this new cultural centre was housed within the ex-headquarters of the Yugoslav secret police, undoubtedly still wired for surveillance (Marcoci 2012, p. 19).

Nevertheless, the SKC, along with the student cultural centres in Zagreb and Novi Sad, became centres for politically charged and experimental art in Yugoslavia, where artists’ indirect and symbolic criticisms of the state resulted in “some of the most” radical art works in Eastern Europe (ibid., p. 19). The informal Group of Six at the SKC consisted of academically trained artists who sought alternate modes of artistic expression to the socialist modernism taught at the university in Belgrade. The German filmmaker Lutz Becker’s film Kino Beleške (Film Notes) captured the innovation of conceptual and performance art, which located the body as artistic medium at the centre of art and which created a radical atmosphere of experimental artistic production in Belgrade.2 Speaking about the conditions under which he made the film in 1975, Becker noted, “Operating in a sphere of limited tolerance and public indifference” fuelled a certain “energy and internalized aggression” (2006, p. 393), which was fundamental to this new incorporation of the artist’s body.

The artists’ frustrations with the supposed freedom to travel, along with the concomitant repression of independence and critical thinking in the country, fuelled their aggression towards the system, which propagated the idea of independent socialism for the people, who were to be active participants in the formation and longevity of the socialist state. The fact that Tito relaxed the Yugoslav borders with the “red passport,” a pass that provided citizens the opportunity to travel to the West, seemed more than promising, and many artists took advantage of this prospect, unique and singular in the context of East European state socialism (Timotijević 2005, p. 9). However, as Slavko Timotijević, curator and art critic at the SKC, pointed out, Tito opened up the border in order “to release himself from awful social [and international] pressure” and to create a uniquely “enlightened communism (that is, soft totalitarianism)” (ibid.) in the Eastern Bloc. Yet this form of socialism used “hidden strategies and methodology of power, planned total control wrapped in the cover of self-management, democracy and apparent civil freedoms” (ibid.).

Knowing very well that such civil freedoms were nothing but a farce, Rasa Todosijević produced works that encapsulated his tenet: “Our sole treasure is our bodies and our ideas” (Todosijević cited in Sretenović 2001, p. 27). Todosijević saw the body and its subject, the self, as the primary instigator of art, and he believed that “the way in which an artist asks a question about art is a work of art” (ibid., p. 26). But beyond thinking of the individual body, Todosijević presented poignant denunciations of his own gender by conveying exaggerated authoritarian masculinities clashing against the femininity of another body, that of his wife Marinela Koželj. In 1974, when the artist participated in the famous April Meetings for Expanded Media that Dunja Blažević organized at the SKC in Belgrade, Todosijević presented Drinking Water (Pijene Vode), one of the most potent examinations of gender politics in the Yugoslav alternative scene at the time. This work would also be seen by such internationally renowned artists as Joseph Beuys, who participated in that April meeting and who had already met SKC artists and observed their performances at Richard Demarco’s Edinburgh Festival in 1973.

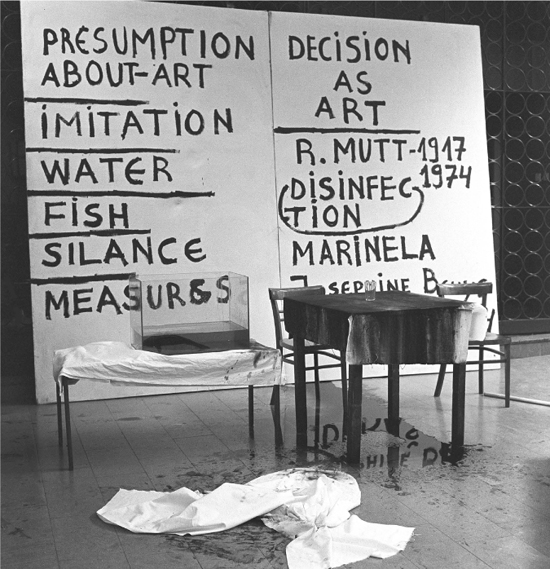

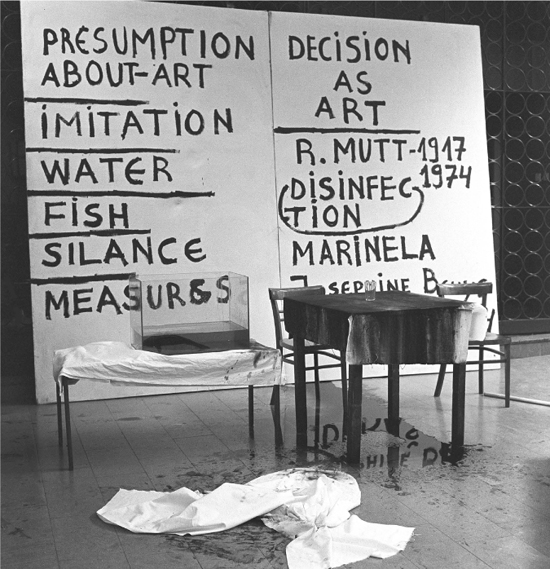

Bearded and bare-chested, Todosijević grabbed a carp weighing “1 kilo and 200 gr. fish” and threw it “in front of the public.” A large white board illustrated with words and phrases written in capital black letters, such as “PRESUMPTION ABOUT – ART” and “DECISION AS ART,” served as the backdrop for this action. Over thirty-five minutes, Todosijević drank 26 glasses of water and attempted “to harmonize the rhythm of swallowing with the rhythm of the dying fish breathing on the floor” (ibid., p. 59). As the fish gasped for its life, needing water to breathe, Todosijević drank water and followed the pace of the animal’s attempts to breathe with the pace of his own swallowing efforts. This soon resulted in Todosijević vomiting water and gasping for oxygen. Prior to the performance, Todosijević had scattered powdered violet pigment on the tablecloth covering the table at which he sat consuming water. The pigment discoloured the white cloth as it became saturated with water and vomit (ibid.). Todosijević continued his action until almost all of the cloth was stained with the violet pigment, and the fish died (ibid.). Marinela Koželj sat next to him with a stoic expression throughout the action.

Two essential themes in Todosijević’s complex art are decisive to an understanding of this action: the question of religion and its relation to art and politics, and the classic position of the male artist as perpetrator. Todosijević’s killing of the fish, a symbol of Christ, resonates with Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation that “God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him!” (2001, p. 120) For Nietzsche, God does not have a place in modern society, and society caused his obliteration. Next Nietzsche asks, “Do we not ourselves have to become gods merely to appear worthy of it?” (ibid.). Given this context, I ask: might one then see Todosijević’s performance as a commentary on the abandonment of God, and his subsequent silence, in socialist and (more broadly) modern society?3 In addition, Todosijević’s decision to kill the fish as art could be said to enact Nietzsche’s idea that the artist comes closest to the truth of life, and takes the place of – or imitates – God by taking the life of the fish. Todosijević enhanced this religio-philosophical context by using the colour purple, which is one of the six original liturgical colours used in the Eastern Orthodox Church (the others being white, green, red, blue, and gold), followed by black vestments and in some places, scarlet orange or rust.

Under state socialism, such art actions turned the studio, or an alternative art space (like SKC), into a sanctuary, a second public sphere where artists could express the symbolism of dissidence that was more often than not misunderstood by the state, and where the artist functioned with the aura of a priest and even a healer.4 In addition, totalitarianism mythologized the East European male artist as a genius, as Serbian curator and art critic Jelena Vesić observed in her introduction to PRELOM’s exhibition SKC in ŠKUC: The Case of Students’ Cultural Centre in the 1970s. She wrote that “‘critical art’ created inside the Socialist state can only be the representation of an individual rebel in totalitarian society stereotypically represented through the skinny body of the [male] performer in the gloomy alternative (art) space” (Vesić 2008, p. 4). Todosijević embodied every aspect of this myth including placing a woman, Marinela Koželj, in the passive role of observer and observed.

Photo: Marinela Koželj.

In Drinking Water, Todosijević also placed the compliant Koželj strategically in front of the right side of the board featuring the phrases and names: DECISION AS ART; R. MUTT – 1917; DISINFECTION 1974; MARINELA; JOSEPHINE BEUYS; T. D. RASA. Neatly dressed and calm, Koželj provided a visual manifestation of balance and reason, in stark contrast to the vomiting God-like artist and the dying fish. Viewers could find solace in Koželj’s personification of the norm (seated, calm, dressed), but also empathize with her painful position as a witness prevented from intervening. She was the concrete manifestation of the “stability” in Todosijević’s battle and its “disinfection.” Todosijević placed Marcel Duchamp in the same role for having initiated the concept of the readymade in 1913 with the Bicycle Wheel, or when he famously signed a urinal R. Mutt in 1917. Indeed, Todosijević’s indebtedness to Duchamp, and perhaps even his female double, Rrose Sélavy, had become evident two years earlier when the artist exhibited Marinela in Drangularium, the first SKC exhibition (also curated by Blažević in 1972). Inspired by Arte Povera’s emphasis on “found objects,” Marinela represented just such an object, and she became a standard feature in most of Todosijević’s early actions, including Drinking Water. Todosijević used her to fill the absence of women artists in the SKC exhibition space, and more broadly, in the history of art, at the same time as he objectified her. In this regard, Todosijević’s battle with water begs a feminist examination.

In her book Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche, published in 1980, the French feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray began to examine how water, as an uncontrollable and immeasurable substance – like the silence of God – has always been understood through the phallic emphasis on solidity and containment driven by a fear of fluidity, i.e. the fear of women. “But (I) no longer wish to return into you,” Irigaray wrote to Nietzsche in Marine Lover. “As soon as I am inside, you vomit me up again” (Irigaray 1991, p. 12). Irigaray’s insights help point out that in his art action, Todosijević consumed and purged himself of water, signifying the patriarchal impossibility of understanding women’s experiences. His decision to face death as art, and become God-like, speaks to Irigaray’s exclamation to Nietzsche: “And what a struggle that impossible choice wages within you! To be or not to be only one, isn’t that still your dilemma? And you have invented no grammar other than the one that creates the gods – that makes you god” (ibid., p. 66).

Todosijević embodied this “impossible choice” by evoking the female as witness, whose sensitivity mediates his violence, disinfects presumptions about art, and inspires the male artist to feminize himself, in the multiple forms of what Todosijević described on his wall text as “Josephine Beuys” (Joseph Beuys’s anima),5 Marcel Duchamp (doubled in Rrose Sélavy), and Todosijević’s own feminine mirror image, Marinela. Is it any wonder then that exactly in the same period as Irigaray was writing Marine Lover, Todosijević orchestrated his most infamous performance series, in which the artist would receive no answer to his question (and the title of a long series of actions): Was ist Kunst? (1977–1978). In this powerful series, the artist incessantly whispered, grunted, screamed, begged, whined, and asked the question “Was ist Kunst?! (What is Art?!)” while looking at the impassive Marinela (his partner/double and representative of women). Despite his plea for an answer, Marinela ignored Todosijević’s screams and remained silent. It would take another woman to scream in response. Irigaray would reproach Nietzsche’s silence, his apparent inability to hear and to answer, by asking:

Are you waiting for me to scream out so loudly in distress that the wall of your deafness is broken down? For me to call you out farther than the farthest recesses you frequent? Out of your circle? … Endlessly, you turn back to that enigmatic question, but you never go on, you leave it still in the dark: who is she? Who am I? How is that difference marked?

(Irigaray 1991, p. 12 and 67)

Such a text illuminates Todosijević’s struggle, both with water and with the question of the identity of art. The battle was as much with himself as it was an encounter with the ethical and aesthetic dilemmas of art and its role in society, all played out within the public space of the SKC. Todosijević always decides – in art – to remain the patriarch, the villain, the provocateur, as if following Nietzsche’s decree: “We have also to be able to stand above morality – and not just to stand with the anxious stiffness of someone who is afraid of slipping and falling at any moment, but also float and play above it!” (Nietzsche 2001, p. 105). Todosijević took just such risks, without the guilt that Nietzsche insists gets in the way of creative genius (ibid.). The SKC served as the very space where such provocation without guilt was possible, a second public sphere where an artist like Todosijević could display the violence, failures, and struggles of his masculinity, all the while using his body to elevate the intimate relationship with his partner and his art to the public realm.

A better example of, and engagement with, Irigaray’s question of just how that difference between men and women is marked was the subject of another artist, from Zagreb, a city with an even longer and more illustrious avant-garde tradition and certainly the most powerful feminist artist of the period, Sanja Iveković. Iveković vehemently resisted and systematically undermined patriarchal containment and exposed misogyny in politics, advertisement, history, art and visual culture, and brought even more forcefully to the forefront the tension between public and private space. Zagreb, like Belgrade, was an important centre for experimental art in Yugoslavia, and Iveković was a leading artist in a scene primarily dominated by men. In Practice Makes a Master (Übung Macht den Meister, 1982), the artist wore a little black business or cocktail dress, high heels, and a white plastic bag over her head. She repeatedly collapsed and got up again while one of Marilyn Monroe’s songs from the movie Bus Stop played, along with “the jarring clamor of guns and other machines from video games, recorded by the artist in New York the previous year” (Iveković 2008, p. 134; Iveković 2009). As Tom Holert observed, Iveković became a “performing body – defaced, decapitated,” but a body that “speaks, though deprived of a voice [that] incorporates the secret of a somewhat obscene … knowledge of violence directed against women” (2008, p. 27). As one without facial identity and despite her effort to gain control over herself, Iveković performed as one unable to communicate, a silenced woman struggling to stand.

Battling with the gruelling mechanisms of subjugation while embodying them, Iveković could be said to have demonstrated a principle later articulated by Judith Butler when she noted that “the moment in which choice is impossible, the subject pursues … subordination as the promise of existence.” Such a “pursuit is not a choice, but neither is it necessity,” Butler continued, as “subjection exploits the desire for existence, where existence is always conferred from elsewhere; it marks a primary vulnerability to the Other in order to be” (1997, pp. 20–21). In continually getting up and falling, Iveković exposed one’s susceptibility to the vicious forces of violence. By enacting these conditions in-and-as art, Iveković broke through the constraints of Butler’s “impossible choice” and bore witness to women’s subjugation and forced conformity, as well as the self-negation that such psychic and bodily events impose from within.

Three years earlier, she performed her now infamous work Triangle (Trokut). Seated on the balcony of her apartment during a visit to Zagreb by President Tito in 1979, Iveković deliberately provoked the attention of security personnel on top of the roofs surrounding her apartment, officers that she assumed would observe her with binoculars and alert the police that something was amiss on her balcony. Reading a book, sipping whiskey in an American T-shirt, and gesticulating as if masturbating, she incited the police to make her leave the balcony and stop her disgraceful behaviour. This intentional “act of disobedience,” as Branka Stipančić called it (1998a, p. 59), disclosed the Yugoslavian government’s security measures forbidding citizens from viewing the President from their windows or balconies. But Iveković inverted the gaze, confronting the watchdogs of the state with her own calculated measures of surveillance to expose their fear of a female threatening their control by ignoring the President, reading a book on Marxism, drinking whiskey in broad daylight, and pleasuring herself.6 It took less than eighteen minutes for the police to intervene and stop her private act in a public, highly politicized, and surveyed space.

She also featured issues of how public space invades private lives in her 60-minute multimedia performance Between Us (Inter Nos, 1978).7 Iveković situated herself in a room separated from the audience where, facing a TV screen, her actions were recorded by a video camera pointed at her and the television. One at a time, visitors could enter another room in which a television transmitted the images from the video camera recording Iveković’s actions, thereby allowing each visitor to see her interaction with the simultaneous recording of their own facial expressions and body movements. Iveković caressed and kissed their televised faces on the screen while participants concurrently interacted with her video image. Similar to the intimate mechanics of a dance with a stranger, the artist and participants found themselves leading one another in an intimate, quasi-romantic and erotic interaction, fittingly accompanied by a recording of Claude Debussy’s “Clair de Lune,” a composition based on Paul Verlaine’s 1869 poem of the same name.

The physical separation of Iveković from the visitors, “speaks of isolation, of being closed in, and demonstrates an effort to break through,” according to Stipančić. It also depends on the mediation of video, which served as both “a hindrance to and a channel of communication” (1998a, p. 59). The performance suggests how the limits of communication rely on structures of performance that hinge on “an interplay of subjectivities established and transmitted in body gestures, systems, and relations” (Stiles 1992, p. 96) mediated by objects. In other words, the performance was plagued by the absence of actual intimacy, rendering the geographic and psychic distance between two people palpable while also the sense of proximity equally nullified intimacy.

Strikingly, Iveković’s performance evoked relations that exceeded hetero-normative affection and intimacy. For during the performance, she kissed, touched and embraced another woman, who willingly participated in this intimate exchange of suggested bodily contact. Inter Nos, mediated by the screen and dependent on an imagined haptic encounter, took effect in a confined and simultaneously secured closeted space of each room, safe from public intervention. At the same time, it was also a space that was public by the nature of being an art event: the public had access to such exchanges of intimacy, and these experiences were then raised to the sphere of culture and art. Iveković’s action could be said to have initiated moments when, as Jill Dolan suggests, “audiences feel themselves allied with each other” and the public (2005, p. 2). Moreover, Iveković’s actions call to mind José Esteban Muñoz’s understanding of queer futurity in which alternative political and social relations can pose utopian possibilities for society and art (2009). As such, the private sphere of touch, interrupted by the screens of artist’s multi-medial mode of communication, incited the blurring of social and political barriers that so vigorously discipline interpersonal and public relations.

The Croatian performance artist Vlasta Delimar most explicitly broke the boundaries between the personal and the public by embodying and performing the illicit desires of women, and challenging the paradigms of normative sexuality while paradoxically resisting alliance with feminism. Like performance artist Tomislav Gotovac, Delimar is renowned in Croatia, but ignored internationally. Quoting Marina Gržinić’s identification of Eastern Europe as the “second world” (2011, p. 27), I would like to suggest that unlike Marina Abramović and Sanja Iveković, Delimar is the “second world’s” least desirable export to the West. Her work has been left out of most exhibitions on performance and other kinds of art from Eastern Europe and especially the Balkans, with the exception of Bojana Pejić’s exhibition Gender Check (2009). Delimar was also omitted from the art group IRWIN’s book East Art Map (2006) and Piotrowski left her out of In the Shadow of Yalta (2009). She does not appear in other important surveys of the region. Why? I propose that, similar to the reception of Carolee Schneemann, Delimar has been charged with producing pornographic, narcissistic, exhibitionist work that is too sexually explicit. Unlike Schneemann, Delimar never identified herself as a feminist. Indeed, she has been called a “miso-feminist,” especially because her art openly proclaims a desire and love for men, and therefore has often been interpreted as misogynist. Such negative appellations ignore or purposefully reject the unprecedented ways in which Delimar confronted female sexuality not only in Croatia but also in the region.

Ljiljana Kolešnik characterizes Delimar’s work as “intuitive feminism” with “its specific and open sexual coloration … a unique phenomenon in our country that had no parallel even then, and there is none today” (1997, pp. 197–201). Reducing Delimar’s artistic approach to “coloration,” however, ironically typifies the ways in which her rigorous critique of sexuality is frequently not taken seriously. Delimar had no trepidation about the circulation of her images and the titillating possibility that she might be touched and played with through the metonym of her photographs. She even proclaimed in the title of one work, I Love Dick (Volim Kurac, 1982). Photographed with naked men holding their penises in her hands, Delimar frequently exhibited sexually explicit acts both in performance and two-dimensional works. Her unapologetic proclamation of loving the penis, sex, and pleasure ran counter to some feminist theoretical and political interventions that considered such imagery to belong to the objectification of women. However, drawing on much earlier works by Schneemann that opened the aesthetic door to women throughout the world to not only be the image but to make it, such as in Schneemann’s ground-breaking photographic essay Eye Body (1963), her happening Meat Joy (1964) and her film Fuses, (1964–1967), Delimar freely displayed her heterosexual desire and pleasure to the world, images that resulted in fascination, accusations of impropriety, laughter in the art world, and exclusion from the histories of art.8

What many of those laughing missed was how she assaulted totalitarian, nationalist, and religious foundations in Yugoslavia. While feminists like political scientist Sabrina Petra Ramet could write in 1995 “Yugoslavia did not, of course, speak of overthrowing socialism,” but instead emphasized “the need to overthrow patriarchy and of the failure of socialism to do so,” (1995, p. 226) Delimar had already produced a vehement critique of patriarchy and the state in Fuck Me (Jebite Me) in 1981, when the artist invited everyone to penetrate her: men, women, the state, religion, socialism, feminists, anti-feminists, etc. For the verb Jebite indicates the plural of “fuck,” while the golden crucifix of the Catholic Church pictured between her breasts, and her strategic placement of a miniature roundel of a church, emerging as a red phallic architectural object on top of her vagina, all point to the collusion of the church and state in the control of women’s bodies. For Miško Šuvaković, Delimar’s work represented a “break-through in the representation of Catholic ‘sin’ with all of its otherwise invisible ideological folds, promises, and prohibitions” (2003, p. 68).

Such criticism of the church took place within the context of Tito’s so-called unified Yugoslavia, a state in which citizens were not allowed to celebrate their own national heritage openly, and to do so had already caused arrests by the 1970s, most famously that of Franjo Tuđman, who later became the leader of Croatian nationalism and the first president of a newly independent Croatia in 1992. National identity in the republics of the former Yugoslavia was deeply tied to religious convictions and constructed “narratives of suffering,” as Ivan Vejvoda has described them (1996, p. 20). This was true especially following Tito’s death in 1980, when uprisings in all the republics indicated a return to religious and ethnic divisions. In fact, in 1981, a massive rape controversy emerged in the Yugoslav media when “Albanian men allegedly began vindictively raping Serbian women,” and the media framed the discussion around those rapes as “interethnic” rather than what Sabrina Petra Ramet calls “intersexual” events (1995, p. 229).9

In her political and psychic aesthetic intervention, Delimar called the hidden patriarchy of totalitarian, nationalist, socialist, and religious institutions alike to account for themselves. Covering her eyes in Fuck Me signified the ways in which the state and church blind(ed) women to their violent corporeal abuses. As Rebecca Schneider has argued about feminist performance, “Something very different is afoot when a work does not symbolically depict a subject of social degradation, but actually is that degradation, terrorizing the sacrosanct divide between symbolic and the literal” (1997, p. 28). Such a view requires consideration of whether or not Delimar embodied “social degradation.” Considering that the phrase “fuck me” also implies to cheat, betray, or victimize someone, an invitation to be “screwed,” meaning deceived and oppressed, summons the perpetrators to display themselves. Moreover, the artist’s frequent references to dicks, fucking, being fucked, smelling genitals, and blood protruding from vaginas, further evokes the experience of millions of women who have undergone the psychic death of rape, and the thousands that, because of their religious and ethnic backgrounds, would encounter such traumatic events during the Balkan wars of the 1990s. Thus does Delimar symbolically depict subjects of social degradation rather than actually degrade herself. Instead, she is the author of a metaphorical image of defilement – one that has public resonance, but which is metonymically conveyed through her private body.

Homoeroticism and the reconfiguration of masculinity as critiques of the political system became most pronounced with Sven Stilinović, who embodied an alternate masculinity as a mode of rebellion. His artist colleague and friend, Vlado Martek, described Stilinović as a “solid anarchist (his well known maxim: either all or none),” the “boyfriend of many girls,” and a “particularly cool person” (1998, p. 10). Sven Stilinović’s pedigree as an anarchist derived in no small measure from the photographs he exhibited of himself accompanied with texts by such figures as the libertarian socialist and self-proclaimed anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, as well as by the Marquis de Sade and others like Karl Marx. In his 1980 Untitled (Bound Figure), Stilinović is shown sitting on a chair bare-chested with his legs, hands, and neck bound with a rope and his mouth taped shut but staring straight at the camera. The caption for the photograph is a quote from Marx:

In the same way in which he produces his own production for his negation and for his punishment, and in which he produces his own product for the loss of a product which does not belong to him, he also produces the ownership of the one who does not produce, the ownership of the production and a product. In this way, work is alienated from the worker and at the same time appropriated by a stranger to whom this work does not belong.

(Milovac 2002, p. 88)10

Presenting himself in Untitled (Bound Figure) as the embodiment of Marx’s text, the artist exhibits himself punished and silenced, yet also in the process of producing his own labour from which he is simultaneously alienated. His aesthetic labour does not belong to him and, in an ironic twist, he has appropriated it from Marx, who himself has been appropriated by the socialist state that punishes and silences its citizens. This is a picture of the proverbial Ouroboros, the snake that bites its own tail as a metaphor for self-reflexivity and/or eternal return. But in this case, the return is the endless submission to Marx’s analysis of labour, ownership, the stranger as the state that appropriates the artist as its own. Stilinović’s smile as he gazes into the camera is inscrutable. But his smile suggests that the artist’s visual exegesis has not only appropriated Marx to reveal his theory as itself appropriated and abused, punished, and silenced by its authoritarian socialism, but also has triumphed in having understood and objectified this process, all the while being forced to submit to it while simultaneously transforming it – through his control of his aesthetic labour – into a vision of pride and self-regulation.

In her discussion of the work, Stipančić surmised: “The emphasis is on the autonomy of the individual as opposed to the state, as well as on resistance to all the forces within a person that deprive them of their right to arrange their life according to their own needs.” Stipančić added that Stilinović “highlight[s] rebellion as a natural creative negation which abolishes all alienation and stresses the innate dignity of human beings and their wish to fully assert themselves in action” (1998b, pp. 103–104). Equating such self-castigating representations of a male artist with the defence of human dignity points to how decision as art deeply undermined the estrangement of some artists by attending to how they individually resisted their bodies being owned by the state. Such attention to corporeality by a few artists in Zagreb led them to investigate socially suppressed aspects of sex and gender, and artists like Sven Stilinović linked their work to desire manifest in a range of forbidden sexualities.

Stilinović’s consistent attention to and emphasis on the interconnections among sex and violence, and their imbrications in the socialist hegemony determining even the ideological foundations of sexuality itself in the East, suggest a nascent visual discourse that anticipated queer politics, a Western term coined in the late 1980s to describe sexual politics that challenged or subverted hetero-normative conceptions of both male and female sexuality. In Svengun (Svenpištolj, 1984–1986), Stilinović lies naked on a bed with a beautiful white rose in his hands. The artist’s large flaccid penis rests on his leg, a phallic image magnified by a disproportionately large collaged photograph of a gun glued on top of the photograph that points not at the artist but at the photographs framed on the wall above him. By exposing himself as vulnerable, alone, languid, and feminized with a rose (Olympia or Odalisque-like), yet dominated by large phallic gun pointed at art (possibly his own art) hanging on the wall above his reclining body, and also by making himself available to the sexual imagination of both men and women, Stilinović not only disturbed but also threatened the naturalized image of the heroic, self-contained, invulnerable Balkan male.

As such, Untitled (Bound Figure) and Svengun undermined the hyper-masculinity associated with the Balkan region. Georg Schöllhammer associated such male figures as fictions of the “unique ideal of masculinity” borrowed from “the unknown, imaginary ‘West’” which served as an “ideal anti-type,” comprised of “dandyism, social waywardness and rebellious, adolescent gestures” (Schöllhammer 2009, p. 140). Calling the West “unknown” is an exaggeration, as artists in Eastern Europe had access to and were familiar with the work and personae of such artists as Andy Warhol, and Stilinović’s self-representation was certainly informed by such artistic discourses. In addition, Schöllhammer’s emphasis on disobedience recalls the strong interest by both Eastern and Western leftist artists in the eroticized figures of such groups as the Baader-Meinhof (Red Army Faction) in Germany, whose sexual openness and radical politics added to their fame and public fascination. That allure persists today, evinced in Uli Edel’s blockbuster film, The Baader Meinhof Complex (2008), and Bruce LaBruce’s Raspberry Reich (2004), a pornographic and queer parody of the Red Army Faction. The beginning scene in LaBruce’s Raspberry Reich, for example, shows a male character in front of a huge Che Guevara poster, stroking and licking a long phallic gun. Sven Stilinović’s Untitled (Bound Figure) of 1980, as well as his Svengun of 1984–1986, anticipated the types of images in LaBruce’s film by some two decades. These works also paralleled the rise of the gay rights movement in Slovenia at the time, such as the founding of the non-governmental gay rights organization Magnus in 1984, as well as alternative artist and music groups like Laibach and Borghesia, which embraced the celebration of leather culture and other forms of non-normative or (what were considered) deviant sexual desires, and which could thrive within the second public sphere.

During this same period in the early to mid-1980s, Stilinović appeared naked on the cover of Zagreb’s newspaper Studentski List (Student List). What makes this photograph so volatile is that he is sitting with the artist Radomir Radovanović,11 and resting his hand on Radovanović’s thigh. Radovanović, in turn, tenderly touches Stilinović’s shoulder. A red triangle strategically covers Stilinović’s penis, but the semiotic implications of the colour are all too clear: they signal the patriarchal authority of state socialism, writ large as homophobic, and, more dangerous for the artist, are suspended in his art. For the “boyfriend of many girls” keeps his eyes closed and is relaxed while the erect triangle points to another man, suggesting a homosexual relationship between them.12

This photograph was created, in part, to advertise the exhibition Collective Act (Kolektivni Akt), organized by Davor Matičević, an openly gay curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, who announced on the cover of Studentski List:

We are taught the stories and legacies of the ancient stones that nurtured a cult of the body. Because of this tradition today, tourists besiege Greece. However, at the present time, nothing of this sort seems interesting to the audience with regard to the relation of the (male) artist as – model (nude) – work; and two thousand years later, we still deal with the discovery of something that once was “normal.”

(Cover of Studentski List, 1981)

Figure 13.2 Cover of Studentski List, 1981.

Photo: Mijo Vesović, Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb, Archive.

This exhibition undermined the paucity in socialist art of representations of nude male bodies with genitals exposed, as well as the veritable taboo on representations of homosexuality.13 In the socialist context, images of men were characteristically portrayed as partisan fighters, communist officials, or stylized rigid caricatures of nude male figures in Greco-Roman art. Presenting the image of the eroticized interaction of two men on the cover of the newspaper was tantamount to advocating for a feminized, homoerotic, overt East European male archetype with its origins in the ancient art of Greece.

The works of Todosijević, Iveković, Delimar, and Stilinović surveyed here explicate the artists’ political commitment to placing the private within the political realm of the public, pushing the intimate into the social by way of decision as art within the second public sphere. What then does “decision as art” mean for former Yugoslavia? And how does it square with performance? I would like to return Drakulić’s observation that totalitarianism resulted in the “politicisation of citizens” in socialist Yugoslavia. As my analysis has shown, this process of politicisation, while violent and oppressive, also produced generations of artists who understood that making art is a political decision that bears real life consequences, anticipating much of institutional critique in contemporary art today, both in the East and in the West. The title of my essay, “Decision as Art: Performance in the Balkans,” references the central leitmotiv of Rasa Todosijević’s actions throughout the 1970s. Performance art bore a special affinity to various forms of political resistance in Eastern Europe, the incorporation of the body as art represented the “transformation of figurative representation into embodied presentation” (Stiles 1992, p. 91). Such embodiment was a political decision for the artists, who, under the constant spectre of the state, made informed and courageous decisions to question and deconstruct what art can and should be, and what we, as people, can do to resist the normative parameters of social relations, civic engagement, and political consciousness.

I have argued that such decisions as art resulted in critiques of totalitarian ideologies, socialist, democratic, and religious alike, all built on, and emblematic of, patriarchal constructions of being. While Todosijević’s battle with water embodied the struggle of the East European male artist under totalitarianism, his performance also raised the question of another spectre: that of the East European woman who is silenced and expressionless. Iveković, on the other hand, struggled with and against political and artistic forms of patriarchy. She, along with artists like Vlasta Delimar, exposed the operative mechanisms of relationality and sexual mores under socialism, pushing for alternative models of engagement and sociality with their own bodies and actions. In his implied queerness, Stilinović’s work undermined patriarchy by breaking through social taboos of Balkan masculinity, a decision informed by anarchist critiques of normative sexuality and its links to state oppression, as well as the appropriation of Marxist theories and artistic labour by the state.

Perhaps then these artists’ decisions to make art, to take control of their lives, to offer up their private bodies as forms of interventions and resistance to disciplining measures of nations and states, to view decision itself as a form of art that could generate an alternative space, one of decided political struggle and civil courage, attests to Foucault’s proclamation in 1979: “It is always necessary to watch out for something, a little beneath history, that breaks with it, that agitates it; it is necessary to look, a little behind politics, for that which ought to limit it, unconditionally. After all, it is my work. I am neither the first nor the only one to be doing it. But I have chosen to do it” (1999, p. 134). In this essay, I hope to have joined such thinkers in “doing it,” in looking “behind politics” for that which did, indeed, limit it: decision as art.

1This quote was brought to my attention by Susan Buck-Morss (2002, p. 209).

2Lutz Becker had screened his film “Art and Revolution” at the SKC in 1973, which drew a large audience and became an important subject of discussion. Two years later, Becker returned to make his film about the SKC-artist. See Lutz Becker (producer/director), Kino Beleške (Film Notes), 16mm b&w, 45 mins. With: Zoran Popović (assistant); Dragomir Zupanc and Dunja Blažević (project leaders), 1975. The following people participated: Dunja Blažević, Dragomir Zupanc, Jasna Tijardović, Raša Todosijević, Biljana Tomić, Ješa Denegri, Goran Đorđević, Marina Abramović, Slavko Timotijević, Bojana Pejić, Neša Paripović, Goran Trbuljak, and Zoran Popović. A copy of this film can be viewed at the SKC archive in Belgrade.

3The five letters in Greek that form the famous “Ichthys” stand for “Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter, i.e., Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour.” This definition is taken from “Catholic Encyclopedia” in New Advent, available at www.newadvent.org/cathen/06083a.htm (Accessed June 29, 2017).

4Lóránd Hegyi discussed this phenomenon within the Central European context, noting: “The impracticability of expressing radical avant-garde strategies in the public sphere gave rise to the myth of the avant-garde as victim with the cult following of a secret and proscribed mysterious religion that could only survive in the underground” (1999, p. 32).

5Joseph Beuys had sent Todosijević a letter which he signed “Josephine Beuys.” Todosijević also distributed pamphlets in 1973 at the Edinburgh festival with “Josephine Beuys” written on them, supposedly in protest against the fame of Beuys.

6Cf. British Marxist sociologist Bottomore (1964).

7Produced by MultiMedia Centre (MultiMedia Centar), Zagreb, December 23, 1978. Iveković’s description: “The installation consists of two rooms connected by two closed TV circuits without an audio link, and an entrance space where a direct transmission takes place for the audience. During the entire action the artist is shut in the first room, invisible to the audience. Visitors enter the second room one at a time. A private dialogue develops between the visitor and the artist, as the artist interacts with the visitor’s screen image, provoking their reaction. Concurrently, the audience receives only participant’s image” (Ilić and Rohmberg 2008, p. 100).

8This is true for both Delimar and Schneemann. It took decades for Schneemann to be recognized, and she still has not had a retrospective.

9By 1987, Serbia would pass a law that increased the 5-year penalty to 10 years for non-Serbs who had raped Serbian women.

10Artwork reproduced with quote in Milovac 2002, p. 88. The quote comes from an unknown translation of Karl Marx, “Estranged Labour” from his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844.

11Although difficult to decipher given the position of the body, Janka Vukmir confirmed that the other artist on the cover is Radomir Radovanović. Conversation with the author, June 15, 2013.

12Ivana Bago confirmed that at the time, Sven Stilinović was known for his attractiveness to both men and women and that there was much speculation about his sexual orientation. Bago in conversation with the author, June 14, 2013.

13Klaus Theweleit’s groundbreaking examination of male sexuality and its homosexual implications in fascism, Männerphantasien (1977) was translated as Male Fantasies into English in 1987 and published by the University of Minnesota Press.

Becker, L. (2006). Art for an Avant-Garde Society Belgrade in the 1970s. In: IRWIN, ed., East Art Map: Contemporary At and Eastern Europe. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 390–400.

Benjamin, W. (1991). Das Passagen-Werk. In: R. Tiedermann, ed., Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. 5. 1st ed. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, pp. 40–1060.

Bottomore, T. (1964). Elites and Society. 1st ed. London: Watts.

Buck-Morss, S. (2002). Dreamworld and Catastrophe. The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Butler, J. (1997). The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjugation. 1st ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Dolan, J. (2005). Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater. 1st ed. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Drakulić, S. (1993). How We Survived Communism and Even Laughed. 1st ed. New York: HarperPerennial.

Foucault, M. (1999). Is It Useless to Revolt? In: J. R. Carrette, ed., Religion and Culture by Michel Foucault. 1st ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 131–134.

Gržinić, M. (2011). Linking Theory, Politics, and Art. In: Z. Kocur, ed., Global Visual Cultures: An Anthology. 1st ed. Malden, MA: Wiley, pp. 27–34.

Hart, M. and Negri, A. (2000). Empire. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hart, M. and Negri, A. (2004). Multitude. 1st ed. New York: Penguin Books.

Hegyi, L. (1999). Central Europe as a Hypothesis and a Way of Life. In: H. Lóránd et al., eds., Aspects/Positions: 50 Years of Art in Central Europe. 1st ed. Vienna: Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, pp. 9–42.

Holert, T. (2008). Face-Shifting. Violence and Expression in the work of Sanja Iveković. In: N. Ilić and K. Rohmberg, eds., Sanja Iveković. Selected Works. 1st ed. Barcelona: Fundacio Antoni Tapies, pp. 26–33.

Ilić, N. and Rohmberg, K., eds. (2008). Sanja Iveković. Selected Works. 1st ed. Barcelona: Fundacio Antoni Tapies.

Irigaray, L. (1991). Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche. 1st ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

IRWIN, ed., (2006). East Art Map: Contemporary At and Eastern Europe. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA; London: The MIT Press.

Iveković, S. (2008). Übung Macht den Maister (Practice Makes a Master, 1982). In: N. Ilić and K. Rohmberg, eds., Sanja Iveković. Selected Works. 1st ed. Barcelona: Fundacio Antoni Tapies, p. 134.

Iveković, S. (2009). Practice Makes a Master [Event information]. Available at: www.moma.org/visit/calendar/events/13792 (Accessed May 29, 2017).

Kolešnik, L. (1997). Intuitivni feminizam Vlaste Delimar. Quorum, časopis za književnost, 13(4), pp. 197–201.

Kristeva, J. (2002). Revolt, She Said. An Interview by Philippe Petit. In: S. Lotringer, ed., Semiotext(e). Foreign Agents Series. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA; London: MIT Press.

Marcoci, R. (2012). Art in Transitional Times, Post-1945, 1968, and 2000 in the Former Yugoslavia. In: R. Marcoci, ed., Sanja Iveković: Sweet Violence. 1st ed. New York: Museum of Modern Art, pp. 9–33.

Martek, V. (1998) Rococo Biographies. In: J. Vukmir, ed., Grupa Šestorice Autora, 1st ed. Zagreb: SCCA, pp. 10–11.

Milovac, Th., ed. (2002). The Misfits: Conceptualist Strategies in Croatian Contemporary Art. 1st ed. Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art.

Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The Politics and Performance of Queer Futurity. 1st ed. New York: NYU Press.

Nietzsche, F. (2001). The Gay Science. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ramet, S. P. (1995). Social Currents in Eastern Europe: The Sources and Consequences of the Great Transformation. 1st ed. Durham: Duke University Press.

Schneider, R. (1997). The Explicit Body in Performance. 1st ed. London; New York: Routledge.

Schöllhammer, G. (2009). “Was ist Kunst, Marinela Koželj?” (1976). In: B. Pejić, ed., Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe. Cologne: Walter König, pp. 137–142.

Sretenović, D. (2001). Was ist Kunst? Art As Social Practice. 1st ed. Belgrade: Geopoetika.

Stiles, K. (1992). Survival Ethos and Destruction Art. Discourse: Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture, 14(2), pp. 74–102.

Stipančić, B. (1998a). Body Language in Croatian Art. In: Z. Badovinac, ed., The Body and the East: From the 1960s to the Present. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA; London: MIT Press, pp. 58–61.

Stipančić, B. (1998b). This is Not My World. In: J. Vukmir, ed., Grupa Šestorice Autora. 1st ed. Zagreb: SCCA, pp. 96–100.

Šuvaković, M. (2003). You Can’t Find a Woman, Can You? An Essay on Performers’ Theme-Questioning of Politics, Body and Sex in Vlasta Delimar’s Deed. In: M. Šuvaković et al., eds., Vlasta Delimar: Monografija Performans. 1st ed. Zagreb: Areagrafika, pp. 67–72.

Theweleit, K. (1977). Männerphantasien. 1st ed. Frankfurt am Main: Roter Stern.

Timotijević, S. (2005). Shortcuts Through Serbian Contemporary Art History. In Remek Dela Savremene Umetnosti U Srbiji od 1968. Do Danas/Masterpieces of Contemporary Art in Serbia from 1968 until Today. 1st ed. Novi Sad: Contemporary Art Museum, pp. 5–15.

Vejvoda, I. (1996). Yugoslavia 1945–91 – from Decentralisation Without Democracy to Dissolution. In: D.A. Dyker and I. Vejvoda, eds., Yugoslavia and After: A Study in Fragmentation, Despair and Rebirth. 1st ed. London: Longman, pp. 9–27.

Vesić, J. (2008). “New Artistic Practice” in Former Yugoslavia: From Leftist Critique of Socialist Bureaucracy to the Post-Communist Artifact in Neo-Liberal Institution Art. In: Prelom kolektiv and ŠKUC Gallery, eds., SKC in ŠKUC: The Case of Students’ Cultural Centre in 1970s: SKC and Political Practices of Art. 1st ed. Ljubljana: ŠKUC Gallery, pp. 4–5.