CHAPTER 11

Effective Care Pathways for

Selective Mutism

Introduction

‘Care pathways’ represent a turning point in ensuring quality and equity of healthcare. By describing how local services will provide for a particular condition, care pathways standardize local practice and inform individuals of the support they can expect to receive.

In 2008, an international consensus-based care pathway of good practice for Selective Mutism (SM) was developed by Keen, Fonseca and Wintgens. The aim was to agree and validate key principles underlying the assessment and management of SM through a consensus process involving international experts, in order to create a local care pathway.

Thirteen recognized experts from North America, Europe and Australia participated in the process and agreement was reached on 11 key principles for an SM care pathway.

The aim of this chapter is to explore how these principles have been applied in the development of SM care pathways in the UK and provide a framework for establishing effective local provision.

As practising speech and language therapists (SLTs) from different NHS Trusts in the North and South of England, the authors have all been involved in developing more robust provision for children with SM. Aware that we were not alone, we invited professionals to share their local care pathways via the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) and contacts with education services who had requested training in SM. We have been greatly encouraged by the various contributions that have been made to this chapter, but are aware that SM remains relatively poorly understood. These children still ‘fall through the gaps’ in terms of service provision, with much debate about professional remit and ownership of the condition. We therefore conclude with a flow diagram, which we recommend as a starting point for teams wishing to develop their own care pathway.

Setting the scene

Effective care planning can only be achieved after general awareness-raising about the existence of SM and long-term implications if left untreated. In the last eight years alone there have been a number of moves in the UK which have significantly raised the profile of SM on a national basis. All have been achieved by a few individuals campaigning together as clinical experts and SMIRA representatives:

1.The RCSLT followed the American Speech–Language–Hearing Association’s lead and included SM within the professional remit of SLTs (RCSLT 2006).

2.SM was added to the NHS Choices A–Z of conditions, giving online access to information and appropriate management of the condition, including the need for education and health services to work in collaboration with families.

3.The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for the treatment of social anxiety disorder included reference to SM, alerting health practitioners to the need to consider SM as an alternative or additional diagnosis.

4.The Communication Trust included SM in the range of speech, language and communication needs that would benefit from their support in securing appropriate management and legislation.

The impact of local awareness-raising initiatives and campaigns for service provision has been greatly enhanced with this national backing.

The international consensus – core recommendations

For the purposes of this chapter we have summarized Keen et al.’s (2008) 11 key principles under five broader headings, each of which will be discussed with specific examples of good practice:

•A multi-modal and multi-agency approach to assessment and intervention with local agreement on the first point of contact for those seeking advice and support.

•Provision of training to educate all involved in identifying and supporting children with SM.

•Access to an individualized intervention programme as soon as SM is identified, with an emphasis on parental involvement in real-life settings.

•Progress determined by improved social functioning.

•Access to a dedicated support group or organization such as the Selective Mutism Information & Research Association (SMIRA).

A multi-modal approach to assessment and intervention

International consensus recommendations (Keen et al. 2008):

Each area should agree a specific service or group of professionals who are the first point of contact to advise educational settings and confirm that a child has SM.

Children with SM must receive a thorough assessment, which considers the possibility of co-existing difficulties such as developmental delay and other communication difficulties. Full consideration must be given to all possible relevant factors such as having English as an additional language and any emotional or behavioural difficulties. If there are found to be other difficulties alongside the SM, additional intervention must be provided as appropriate, as well as specific intervention for the SM.

If a child does not make the expected progress despite provision of an appropriate programme for their SM, it will be important to consider the possibility of co-existing difficulties or factors that may be having an impact. If progress is felt to be hampered by severe levels of anxiety, for example, a therapeutic trial of medication (i.e. SSRIs) may be appropriate. Any such additional intervention should be provided in addition to a behavioural programme and should not replace it.

The first step towards such a multi-modal approach is to create a multi-agency team committed to joined-up thinking about the needs of SM children, with an awareness of each other’s roles and remit. At the heart of SM is a communication difficulty – difficulty talking to or in front of certain people as a result of learned anxiety – but there are often additional considerations such as high sensitivity, communication disorders, co-ordination difficulties, second-language learning and other anxieties. Good practice therefore starts with informal multi-agency discussion, leading to more formal meetings to agree a model based on local networks, resources and expertise, followed by workshops and information days to develop information leaflets, raise awareness and share agreed policy, including specific referral criteria for each agency involved.

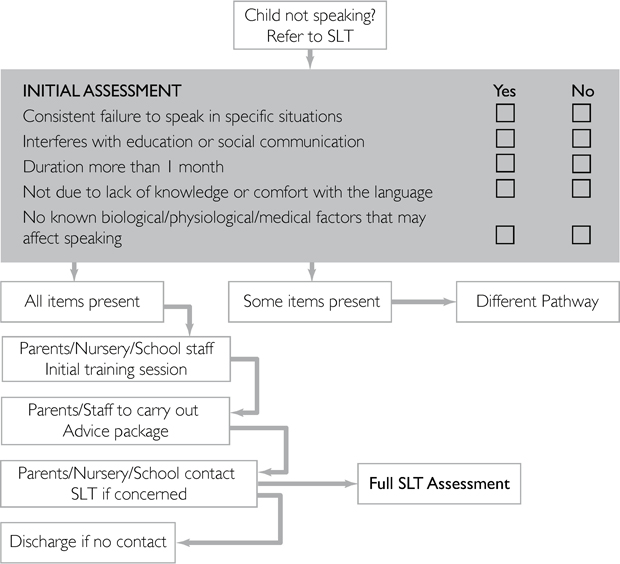

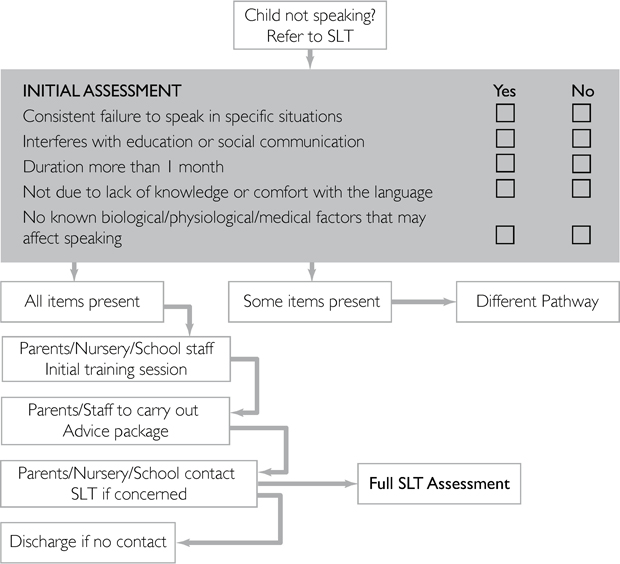

The majority of care pathways we have seen direct initial referrals towards SLTs (see example in Figure 11.1) but Educational Psychologists (EPs) or Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) take the lead in other areas of the UK. Some SLTs only accept referrals when co-morbid speech, language or communication difficulties are suspected (see example in Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.1 East Sussex care pathway: initial identification and referral route

Figure 11.2 Suffolk care pathway: initial intervention and referral routes

Different models are reported to work well in different geographical areas. It does not appear to matter who takes the lead, provided clear referral guidelines are in place with prompt action and agreement regarding how and when other agencies need to be involved. For example, CAMHS may be involved when there are questions around co-morbidity with other mental health difficulties or to address particular issues with family dynamics and parenting. Psychiatric involvement in care pathways seems to be limited to cases where medication is being considered as an adjunct to therapy. One service commented that since the implementation of a joint care pathway involving CAMHS and SLT, medication had not been the chosen treatment option. Another SLT service reported that it had been agreed that CAMHS involvement could usually be avoided with early intervention, but their local CAMHS team provided clinical supervision for more complex cases.

Different practice has also emerged with regard to the nature of the assessment process itself. It would be very unusual for children in the UK to automatically receive a full multi-modal assessment exploring communication, cognition, general development and psychosocial status. The favoured approach is to prioritize consideration of communication and anxiety issues, followed by later referral for cognitive, sensory, physical or other medical issues as indicated by assessment findings, response to intervention and general observation over time.

Four initial assessment routes are evident:

•Joint assessment involving SLT and Clinical Psychologist (CP). SLT and CP conduct a full assessment jointly or independently, followed by liaison to formulate a diagnosis, consider referral to other agencies and agree a management plan involving either or both services.

•Child-focused assessment with a designated service. SLT, EP, CP or Minority Ethnic Achievement Service assesses the child within the context of their own specialism. Observations and parental interview will ascertain the need for onward referral to other agencies for additional assessment.

•Parent-focused assessment with a designated service. As above but the initial focus is on establishing a diagnosis of SM via comprehensive interviews with parents and other key personnel (e.g. class teacher) rather than conducting a face-to-face assessment with the child. Screening questions are asked to decide if full assessment is indicated for any aspect of the child’s development, but the onus is on implementing appropriate intervention as soon as possible without burdening the child with the additional anxiety of meeting a stranger. Should further assessment prove necessary it may be deferred, as it is recognized that findings are unreliable when children are anxious.

•Unofficial diagnosis and management, with the option of assessment. This approach is only recommended in tandem with a rolling universal training programme (see next section). Participants are provided with guidelines for diagnosis and intervention, with clear criteria for requesting specialist assessment and support. This non-invasive approach allows children to work with the people they see on a day-to-day basis in familiar environments and ensures that specialist time is reserved for more complex cases.

These approaches share the pragmatic view that as long as all aspects of a multi-modal assessment are considered, it is not necessary to conduct a full multi-modal assessment routinely. The approaches differ in scope and timing, each balancing the risk of overlooking relevant contributory factors against the risk of delaying intervention. All approaches have their merits, but we observe that, as general awareness in the community increases, the need to officially diagnose SM decreases.

Provision of training

International consensus recommendations (Keen et al. 2008):

As early identification is key in the successful management of SM, and as it is usually within the pre-school or school setting where the mutism manifests itself, it is important that pre-school and school staff receive training to develop their awareness of how to recognize SM. Awareness-raising training should also present accurate information about what does and doesn’t cause SM, and how it should be managed within the educational setting. As it will often be pre-school or school staff who raise the issue with a child’s parents, it is important that they know how to do this with confidence and sensitivity.

There is also a need for ongoing training and professional development amongst the professionals who will be involved in supporting these pre-school and school staff.

We have received many examples of services engaged in awareness-raising amongst pre-schools, schools and parents. Activities include the distribution of information leaflets to support parents and staff in the early identification and management of SM, and universal training to which all local schools and pre-schools are invited, regardless of whether or not these settings have children with SM on roll. Services have commented that it is through attending these training days that staff realize they do know children with SM or at risk of developing it. This is a very positive impact of training, which will ultimately lead to prevention, as reluctance to speak will not be maintained through inappropriate emphasis on talking (Cline and Baldwin 2004).

Services are also delivering targeted training 3–4 times a year as part of their care pathway, inviting staff and parents of identified children with SM. Some services do not accept referrals for specific casework until interested parties have attended an initial training session and implemented appropriate strategies. This demonstrates to parents and staff that they are integral to helping their child move forward and minimizes waiting time for accessing specialist advice.

Some services combine half- and full-day training sessions, with parents and staff of pre-school children attending only the morning session which focuses on awareness-raising and general environmental modifications. When these attendees leave before the session on formal small-steps interventions, it acts as a powerful reminder that SM can be successfully treated without the need for formal programmes, if identified and supported early enough. In an audit of SM cases carried out in 2013 by East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust (EKHUFT) SLT service, 13 out of 15 children referred as pre-schoolers had overcome their difficulties by their sixth birthday with the support of this training.

Services also recognize the need for training and ongoing clinical supervision amongst the professionals who are taking the ‘expert’ roles for SM – for example, SLTs or psychologists. The Universal SLT service within Kent Community Health NHS Trust (KCHT) conducted a survey amongst its staff in 2013 which revealed a direct correlation between training and confidence levels amongst the therapists. One training tool that has proved to be particularly useful in building confidence amongst professionals is the use of video to demonstrate specific techniques.

Within the UK there is now a framework for SM training for professionals, with University College London hosting a two-day programme each year within the Division of Psychology and Language Sciences. This training is mainly attended by SLTs and psychologists, who cascade the information down to their teams.

In some areas of the UK, professionals have set up local interest groups to provide peer supervision and continuing professional development. One example of this is a SLT-led Kent-wide interest group, which has also been attended by professionals from specialist teaching services, CAMHS and child health. It should not be forgotten that, although each agency’s primary focus will be on supporting children and families, practitioners also need support to share the responsibility of case-management in an area which can be intellectually and emotionally draining for all concerned.

Access to individualized intervention programmes in real-life settings

International consensus recommendations (Keen et al. 2008):

SM needs to be treated as soon as it is identified in order to minimize anxiety for the child, their family and their teachers. Early intervention is more likely to be effective and will reduce the need for more lengthy and complex interventions with older children. Treatment strategies need to be implemented in the day-to-day settings where SM occurs, for example in the child’s home, pre-school or school setting, and monitored via frequent planning meetings. Mutism may be perpetuated by the behaviours and responses of family and teachers and generates negative feelings in the adults involved; parents and school staff should therefore be involved in the intervention process, supported by specialist clinicians or advisors.

Although far from standard practice, many services across the UK are now providing comprehensive packages of care for children with SM and their families.

Common themes which emerge are:

•Confidence in the evidence-based behavioural principles embraced by The Selective Mutism Resource Manual (Johnson and Wintgens 2001).

This practical guide helps parents and professionals reduce children’s anxiety and gradually increase their comfort with talking. The KCHT survey which involved 48 SLTs treating a total of 123 children with SM indicated that these techniques were 91 per cent successful in extending the child’s talking circle, increasing to 96.5 per cent successful if the SLT had attended a full training day. When the techniques were not successful, it was noted that the manual guidance had not been followed (e.g. intervention sessions were inconsistent or infrequent) or that the situation was complicated by the long-standing nature of the SM and the mental health status of the student or parent.

•A focus on early intervention and prevention.

Services are aware that by dispelling the myth that it is safe to wait for young children to ‘outgrow’ SM, the need for more costly or extended intervention at a later date will be reduced. Various initiatives are in place to provide early years settings with appropriate management techniques to support all quiet children as soon as reluctance to speak is noted (see Johnson and Jones 2012). Posters in general practitioner (GP) and health centre waiting rooms, information leaflets on Trust websites and training sessions for early years workers are used to encourage early referral.

•An emphasis on environmental adaptation as a precursor and backdrop to individual treatment programmes.

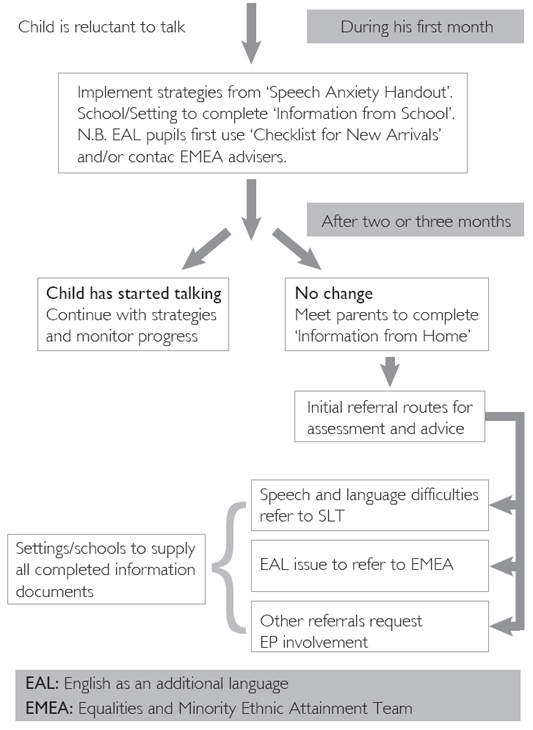

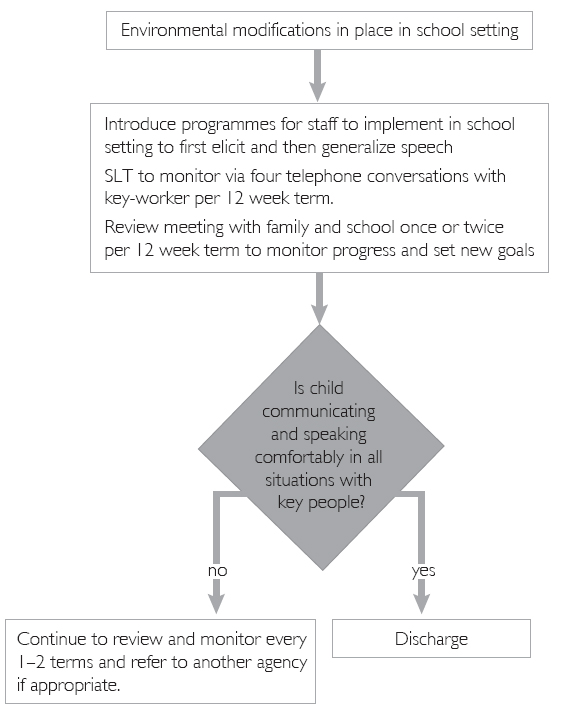

It is recognized that treatment programmes will be ineffective while the child experiences general anxiety or specific anxiety about talking. It is therefore essential to aim for safe, loving and stable home and school environments, and look specifically at adult behaviour that may be maintaining fear or avoidance of talking. ‘Creating the right environment’ is a powerful but low-key intervention which usually effects an immediate reduction in anxiety levels, enabling the child to benefit fully from individual rapport-building or treatment sessions (see example in Figure 11.3). Here the focus of intervention is to help families and early years staff modify their own interaction with the child, so that the child feels under no pressure to communicate but experiences many positive and enjoyable associations with communication. Avoidance is not an option! Rather, parents and staff facilitate participation by making activities more manageable for the child and responding positively to non-verbal communication, until the child feels more comfortable about talking. This is accompanied by desensitization to speaking in public using voice-activated toys and recording devices, for example, and by setting up situations where the child can talk to their parents or friends without fear of being directly questioned by other people present.

Figure 11.3 Extract from EKHUFT care pathway

•Recognition that specialists are usually best placed to advise on the planning and delivery of intervention programmes, rather than working directly with the child.

Taking a consultative rather than hands-on role reflects expert opinion that children with SM will only overcome their fear of talking if they gradually face the fear in the social situations where the fear occurs. It is not uncommon to find that children with SM are able to talk to outside professionals in a clinic setting, enabled by the comforting presence of their parent, the removal of an audience, and the clinician’s skill in reducing anxiety by only gradually increasing the communication expectations. Continuing to work with a clinician in a clinic setting has very limited value for the child with SM, as it adds only one new person to their talking circle – a person who plays no part in their day-to-day life.

Eliciting speech with one individual is only the start of the process. Children need support to generalize to a range of people, activities and settings and to use their speech at a functional level to meet their needs. Only adults who see the child on a day-to-day basis are in a good position to facilitate this generalization process; the same adults who are well placed to build rapport, secure the child’s trust and be the first person the child talks to in the school setting. Furthermore, adults who are already in frequent contact with the child can provide support over a protracted period of time on a ‘little but often’ basis which is far more effective than lengthy or infrequent individual sessions (Johnson and Wintgens 2001). They have greater flexibility than outside professionals when it comes to managing the practicalities of delivering a school-based programme, and by taking on the role of key-worker they free the child from the potential stress of engaging with a stranger in an unfamiliar environment. Such commitment to children with SM would not be possible without goodwill, training and ongoing specialist support, but we can be proud that in the UK the resource for this form of service delivery is generally found by schools following the SEN Code of Practice.

However, it can be advantageous for outside professionals to invest time in developing a relationship with the child and eliciting speech by ‘sliding-in’ as the child talks to a conversational partner (usually the parent). They can provide the family with a model to imitate when ‘sliding-in’ a friend or family member that the child does not talk to. Using first-hand knowledge of the child’s anxiety and comfort triggers, they can repeat the ‘sliding-in’ process with a school-based member of staff who will take over as key-worker for the generalization phase. Very importantly, they will gain true understanding of the skills and emotional control that are required to be an effective key-worker, improving their effectiveness and confidence as a consultant and support for school-based staff in the future.

Regular support to maintain momentum and quickly address any issues that arise is essential. This is best achieved through multi-agency review meetings and individual e-mail or telephone contact, as demonstrated in Figure 11.4. Review meetings are deemed most effective if embedded in existing educational policy for multi-agency liaison and individual target-setting.

Figure 11.4 Extract from Ealing Hospital NHS Trust care pathway

•Recognition that SM is rarely restricted to the school setting.

Much of the available literature around SM focuses on school as the main setting where children do not speak, and indeed the child’s school is the favoured setting in UK care pathways for regular review meetings. However, the information leaflets developed as part of each care pathway emphasize that intervention should also extend to home and community settings. Parents may be advised to invite classmates home, for example, or to facilitate natural talking in public by retreating slightly from onlookers rather than offering a willing ear for whispered communications. They may need examples of how to be positive – for example, ‘He’ll be able to talk if you make comments rather than asking questions and let him join in his own time’ or ‘She does it a different way’ – rather than speaking negatively in front of their children – for example, ‘He won’t talk’ or ‘She can’t do that.’

Best practice involves reaching agreement on targets and strategies for both home and school at each review meeting, particularly as our own clinical experience indicates that getting ‘stuck’ in one setting impinges on progress in other settings. A meeting or phone conversation between parents and their designated contact before the review meeting may well be valued and productive. One care pathway includes a termly group meeting for parents, mediated by a specialist SLT. The success of this is put down to the inspiration and emotional support provided by the participants, rather than the resident ‘expert’. The focus is the child’s inclusion in family life and the local community; popular themes include: ‘letting go’ and facilitating independence; helping children manage anxiety rather than eliminating it through avoidance; and the transition to secondary school.

Older children tend to benefit from a mentor rather than parent to support them in achieving targets in their local community – these should be planned according to the student’s personal goals and priorities, be this following a chosen interest or career, using the telephone, shopping or travelling independently, or making friends. This is an area which does not seem to be well developed in current care pathways but we know of individual cases where this mentor role has been taken on by school-based support staff, SLTs, CAMHS workers or staff from local government/careers guidance initiatives. All avenues should be fully explored at a multi-agency review meeting.

Many parents talk of a particular individual or organization in the community that showed real understanding of SM and enabled their child to gradually participate and eventually shine in a particular area of interest or skill. As confidence and freedom of expression increased, there was a ripple effect into other social situations. We feel this is an area that has so far been relatively unexplored, with scope for investigating local opportunities such as charities, youth groups, clubs and volunteer agencies, with the aim of developing a local network of informed individuals and organizations who are willing and able to provide support to young people in the community.

Progress determined by improved social functioning

International consensus recommendations (Keen et al. 2008):

The key criterion for considering that the child with SM is making progress is improved social function. This is demonstrated by an observable increase in non-verbal and verbal communication within a widening range of people and locations, accompanied by decreased social anxiety (as expressed by the child or evident through their demeanour).

The simple act of speaking is not an adequate measure of the child’s progress towards being a spontaneous communicator who initiates interaction with others. There is a danger that ‘she’s talking now’ can be reported and seen as progress away from the child’s mutism, only to find that in fact the child is speaking under sufferance and quietly answering questions with a single word. This is not an indication that the child is any less anxious about the act of speaking or has become a more confident communicator.

In short, a talking child is not necessarily one that is communicating happily, freely and effectively. An ability to meet a widening range of communicative demands through non-verbal and verbal means is, however, a measure of success.

In keeping with the consensus recommendations, we note that checklists are being used to record not only who a child talks to, but whether the child can, for instance, gain a teacher’s attention, express their need for the toilet, contribute to discussions, ask for help, report their experiences (such as unfavourable comments from others), or make choices at school lunch time. Does the child participate in group activities at school and in the community as a valued team member? Such information reveals as much about the knowledge and attitude of others as about the ability of the child to communicate, and provides a focus for education and intervention as well as a means of assessing and monitoring progress. Much of this is captured in the Selective Mutism Questionnaire (SMQ) (Bergman et al. 2008), which provides a measure of verbal communication and comfort in school, family and community settings.

The discharge criteria that accompany each care pathway are a clear indication that support services are using measures of social functioning to determine progress, as illustrated in Figures 11.3 and 11.4. It is a valuable exercise for services to identify discharge criteria in this way, recognizing that older children (late referrals) are likely to complete their recovery after discharge. Nonetheless, personal targets around participation and independence will be of greatest value to teenagers and give them a taste of what they can achieve with a fresh start in a new setting.

Access to a dedicated support group or organization

International consensus recommendations (Keen et al. 2008):

Educational and nursery (pre-school) professionals and parents should have access to the resources available from appropriate support groups (e.g. in the UK, the Selective Mutism Information & Research Association, SMIRA) as soon as SM is identified.

Given the relatively recent rise in interest and understanding about SM amongst professionals in health and education, parents are often left to their own devices when it comes to investigating and managing their children’s mutism. Dedicated websites such as SMIRA are often their first ‘port of call’ and provide not only the vital information they need but also the peer support they were unable to find from friends and family. Even when parents are lucky enough to find local services with the time and expertise to support their child, many comment that it is the day-to-day access to internet chat-rooms hosted and moderated by organizations such as SMIRA that become their ‘lifeline’.

We have found that services working with SM typically refer parents and other professionals to SMIRA via their training packages and advice leaflets. Group training sessions for parents have also provided a valuable forum for parents to share their experiences.

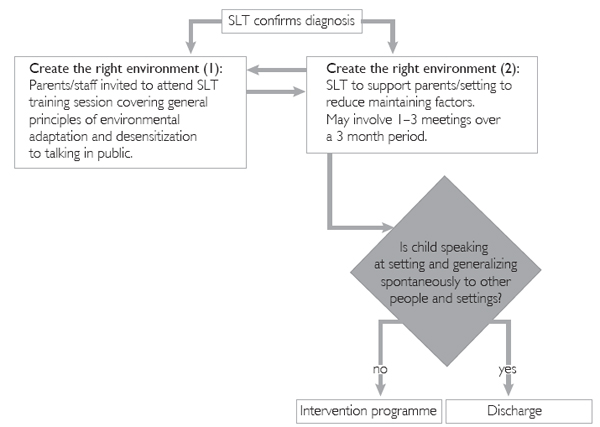

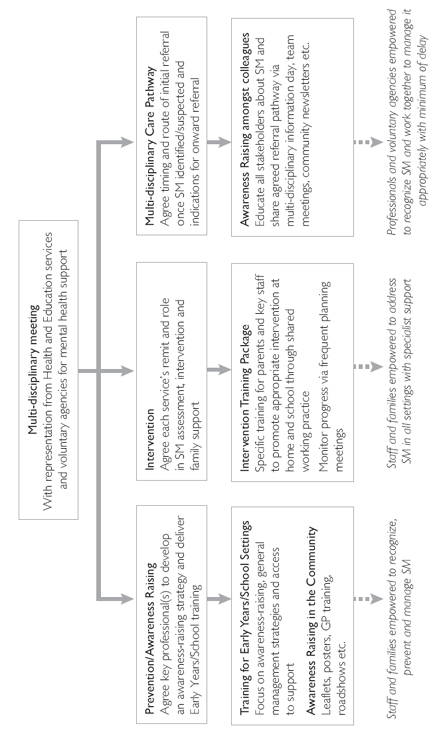

In conclusion

The SM care pathways in use and under development in the UK demonstrate a high level of consistency with the internationally agreed principles set out in 2008 by Keen, Fonseca and Wintgens. We recognize that each locality will vary in terms of which professionals are best placed to support children with SM, and recommend a flexible approach in applying the key principles as set out in Figure 11.5. Ultimately, we would like to see multi-agency care pathways in place so that every child with SM is steered without delay towards appropriate support, regardless of where the child lives and whom the family first approaches for advice. We hope this chapter will encourage readers to consider how they can become more involved in service provision for these children, regardless of their professional background and place of work, leading to collaboration between local services and organizations to agree a unified approach for recognition and management of SM.

Figure 11.5 Multi-agency application of international consensus recommendations

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to our contributors from Ceredigion County Council, Ealing Hospital NHS Trust, East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust, East Sussex Children’s Integrated Therapy Service, Hywel Dda Health Board, Kent Community Health NHS Trust, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust, Suffolk Community Healthcare, Suffolk County Council, Swindon Borough Council, Wirral Community NHS Trust and York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.