CHAPTER 16

Recovery from Selective Mutism

Testimonies from Families No Longer Affected by SM

Katie’s story

Katie (not her real name) and her mother tell the story of her troubles and eventual recovery in their own words.

My Mum recalls how I was always more reserved than other children – even as a baby I was less adventurous than others. When other parents were talking about how they were always running after their children who just wanted to explore, my Mum would always look down and see me by her feet, scared to leave her side.

I somehow had a fear of people outside the family; at home I was fine but as soon as other people were around things would be different. Obviously I had to go to school though. Some children would cry and try and resist being left but instead my whole body just became numb and my face blank. I didn’t want to be there but just accepted I had no choice. I just went through the motions but it would be like I wasn’t really there. My Mum noticed how I would be really chatty on the way to school and then at a certain point I would just automatically change.

To me, it was natural to be quiet and to retreat into my own little shell. I just remember being so overwhelmed by all these noisy children who wanted to be the centre of attention all the time when I just wanted to sit back and watch from the sidelines.

Mother speaks: Katie always seemed happy and relaxed at home or with people she was familiar with and felt comfortable with but was noticeably different in unfamiliar situations. She particularly seemed overwhelmed by playgroups or school. She didn’t cry but seemed resigned and braced herself. I could tell how tense she was, almost robotic, paralyzed with fear. We hoped she was just shy and would adjust eventually. It wasn’t until I talked to her Year 1 teacher about how unhappy she was at school that she informed me that actually in two terms she had never heard her talk!

Plans to help her integrate and speak in small groups never seemed to be put into action. I did think of asking for professional advice but wasn’t sure who to ask and was concerned about making Katie feel more anxious by being singled out. I was also very aware of the potential for her not talking at school being misunderstood. It broke my heart to see her so isolated and occasionally I would see the same frightened rabbit look and inability to speak in other situations. By the time Katie was five she had three younger siblings and her mutism at school began to become entrenched.

With hindsight I wonder if my inability to help or understand left her feeling abandoned and more frightened, which fills me with remorse and regret.

Katie: How it got noticed

At primary school I always had a few friends who I could almost hide behind. They took me under their wing so I was seen as shy but it didn’t become too noticeable until my family moved and I started a new school. Being the new girl when everyone knew each other was difficult and I soon stood out.

It was at this school that the head-teacher noticed something was wrong and spoke to my parents about it. It was at this time, when I was ten years old, that the label ‘Selective Mutism’ was mentioned. My head-teacher said to my Mum, ‘I don’t want to scare you but she has difficulty speaking in class and I think it might be Selective Mutism. I would suggest that you go and see your doctor.’

After seeing the doctor, I was referred to a psychologist from the Community Health Team. Nothing was ever said to me, but judging by the way they dealt with me, I had the feeling people suspected that I had suffered some kind of trauma which had led me to stop talking. I remember having to take the morning off school to go to see the psychologist every week and it just felt like they were trying to get some kind of secret out of me as to why I wasn’t speaking. I think back then SM wasn’t ever heard of so people didn’t understand it as much as they maybe would today. In my experience, it wouldn’t surprise me if parents could be almost too scared to get proper help as it could look suspicious that their children seemed too scared to speak.

In the end I think the specialist nurse said, ‘It’s just her personality’ and they decided to let it rest. When I went to secondary school they were told everything but just kept the information on file and didn’t really do anything. It was in Year 8 when a teacher rang up my Mum and asked her what she thought about seeing a speech therapist. The speech therapist confirmed I had SM so I finally received an explanation about what was wrong with me. My Mum started to do some research and came across SMIRA.

It was a huge relief to finally understand the problem and to know that it was something I suffered from, not something that was wrong with me. Hearing other people’s stories, I didn’t feel so alone, and hearing how people had ‘got over it’ and lived normal lives made me feel like there was light at the end of the tunnel and things would get better. It felt like a community that it felt good to belong to.

Mother speaks: By the time Katie was ten the problem became more pronounced. I had thought about going to a psychologist but was again very wary that it would be misunderstood as a response to trauma or abuse. A speech therapist didn’t seem appropriate as her speech was very well developed for her age. Eventually I did go to the family doctor but, as I feared, the CAMHS nurse didn’t understand it either. In desperation I took her to various alternative health practitioners to no avail. The eventual diagnosis was a relief and SMIRA was a lifeline.

Katie: Bad experiences

Growing up, I remember hearing the phrase ‘your school days are the best days of your life’ and just thinking ‘WHAT?!’ Many people have fond memories of their school days and can reminisce with their school friends about all the fun they had, but this is something that I just can’t relate to. My school days were in fact the worst days of my life.

Every day was filled with dread, loneliness and panic. I remember being too scared to sleep, as I knew what was waiting for me when I woke up. I would sometimes set my alarm for three hours before I actually needed to wake up just so I had time to mentally prepare myself for the day ahead.

Nobody ever wanted to be paired up with me in class and I was always last to be picked for everything. For example, if there were three of us in the group someone would say ‘but there are only two of us, because we have Katie’, as if I didn’t count as a person.

Unsympathetic teachers made it even more difficult. I remember listening to a teacher praising a student after being paired with me (who was horrible to me and kicked up a fuss because she had to work with me), saying she knew how hard it was for someone to have to work with ‘someone like that’ (meaning me, as if I was being difficult). A PE teacher even shouted at me in front of the entire class, telling me I was ‘letting everyone down’.

Teachers would say things like ‘I know you don’t like speaking but…’ as if I had an attitude problem and was doing it on purpose. I found that really insulting and upsetting as I tried every day to speak normally but just couldn’t. To me, it was like telling someone with hearing problems that they don’t like to listen or someone with sight problems that they just weren’t really looking.

I always had to look out for myself because people would treat me how they wanted because they knew I wouldn’t tell anyone or fight back.

Naturally I struggled with oral exams in language subjects. Once at school I had revved myself up for ages in preparation for a speaking assessment in German, only to not be called in to the exam. It was assumed that I would not be taking part, even though I had done all the work and preparation as nobody had told me I wouldn’t be doing the exam. It annoyed me that I was just ignored and pushed to one side and it was frustrating as I knew I was as capable as anyone else. I think in larger schools it is easy to just focus on a few people – the clever ones or the ones who cause trouble. The ones in between who don’t cause any trouble are sometimes forgotten. In my last school I was supported a little bit more as my teacher recognized that I was perfectly able in other areas. However, when it came to my GCSEs I was excused from the oral assessments in English and German as it would have brought my final grade down unfairly. This time, however, I was actually informed that I would not be taking part and it was my choice rather than a decision that had been made for me.

When I was younger, the hardest part of all was that I didn’t know what was wrong with me – nobody understood, not even myself – and I couldn’t work out how to fix it. I was just stuck. I felt like the only person in the world that had this problem, which made it more isolating and lonely. In some ways I envied other people’s problems as they could talk to other people about their issues. Nobody seemed to be able to empathize with me.

I spent most of my time at school by myself, being ignored by most people or having someone talk to me just because they were told to, when I could tell that they didn’t want to.

Altogether I attended five different schools before I went to college. Every time I started a new school I always told myself ‘this time it will be different’ and ‘when I make a fresh start I will start speaking and be normal and make friends’. But it never got any easier.

Katie: Different techniques used

Throughout my childhood it felt like I had tried everything possible to ‘cure’ my SM. I was taken to a homeopath, a cranial osteopath and a child hypnotherapist. I took medication such as Prozac and was offered bribes and rewards. The students at school were even given presentations about my problem in an attempt to help them understand and encourage them to include me and support me. But nothing really seemed to work.

Mother speaks: It was always rather obvious that as it was school where Katie was unable to speak it was in that environment that help should be given. Unfortunately, this never really happened. There was a limit to what we could do at home.

I remember when Katie was learning to swim; no amount of encouragement, pressure or rewards enabled her to find her confidence in the water. One day when we were in the pool with her brother and sisters and I left her to splash around I caught her out of the corner of my eye swimming a very elegant front crawl, completing almost a length of the pool. I always knew that Katie would be okay and would develop her social confidence as she had done in the water. Development should not be treated as a race. Looking back, I think it is about finding a balance between pressure and encouragement, not panicking but not giving up either. I remain full of regret that I was unable to find the appropriate resources to help her or help her myself when she was younger.

No one would know if they met Katie now what she has suffered. I know people are drawn to her quiet confidence. She is trustworthy, loyal, genuine, compassionate and has many and varied interests. Although her confidence can be knocked quite easily, she has developed a resilience and confidence that many would envy. Essentially, Katie confronted and resolved her problem through her own determination. However, involvement with SMIRA was the turning point and we are very grateful to everyone involved for their help and support.

Katie: The cure

I think in a way I knew that while I was at school I would never be able to talk normally and be part of the group. I did feel like everything would be so much easier once I left and that my life would start, so I used my time at school to get the best grades I could and as much experience as I could.

Sure enough, when I started college I began speaking to people. On my first day I was lucky enough to start speaking to someone who quickly became one of my best friends. As she was so chatty, confident and easy to talk to, she made friends quickly and her friends became my friends. Although I was still shy, lacked confidence and found it hard to speak up in classes, I found myself gaining more confidence and making more friends as time went on. Unlike school, I felt no pressure to start talking, it was just expected that I was normal and spoke to people and nobody made a big deal out of it when I did.

There were a couple of people at college who knew me from school and I was scared they would tell people how I used to be, which would prevent me from talking. I remember this happening at secondary school – I was speaking to someone in the first few days (or trying to) and the girl on the other side just turned round and said ‘she doesn’t talk’ and the other girl kind of gave me a funny look and thought I was weird. Sure enough, I couldn’t seem to talk to her.

University was the same, I started off a little shy and apprehensive but I grew in confidence and went on to join lots of groups and societies and even did a bit of public speaking, which made me feel quite proud.

Katie: The present

Looking back, I spent the first 18 years of my life in silence and isolation, suffering from something that made my life extremely difficult in a lot of ways. However, I now see this as my past and not something that will define me or affect my future. Because this is something that I suffered from when growing up, it is hard to tell what my life would be like if I didn’t have it.

I try to stay positive and think about what I’ve gained from struggling with SM. As I missed out on the social side of school, I was determined to do well academically. I focused a lot of my energy and creativity into art and some people recognized my talent, which boosted my confidence a little. Because of my past experiences I think I have gained a lot of compassion and sensitivity towards other people.

I think it’s made me more grateful for normal little things other people take for granted. I remember my first few weeks of college, talking and laughing with my new friends, just feeling so happy and so lucky to finally fit in.

I think there is a part of me that will always be a little bit shy and lack confidence in certain situations, but I know that this is okay and this is ‘normal’. Most people suffer with confidence at some point in their lives, and if not, they are suffering with something else.

I want anyone else suffering from the same thing to know that things will be okay, no matter how long it goes on for and no matter how impossible it seems to be to ever be ‘normal’.

Mina’s story

Alice and Mina (not her real name) tell the story of how SMIRA and peers at school helped her recovery from SM.

Fourteen-year-old Mina appealed in writing to a mentor who was luckily employed at her secondary school. She had been performing well in all school subjects where speech was not needed but was not able to talk to teachers or peers. She really wanted to overcome her problem and was brave enough to make the first approach. The mentor had heard of SMIRA and contacted the charity for advice. It was clear that Mina was suffering from SM and could be helped.

Mina’s father explained that his daughter could talk to most, though not quite all, of their extended family at home, so it seemed that a ‘Circle of Friends’ approach (Taylor 1997) might well succeed, especially if personal contact was maintained with SMIRA through Alice Sluckin.

With encouragement from the school in the shape of drinks and biscuits, a support group was set up and several girls from Mina’s class volunteered to join. Alice and the school mentor were also members of the group. Meetings were only held once a month and Mina still did not talk, but mutual disclosure of how they felt about being at school and why certain topics interested them seemed to bring the girls closer. Mina was no longer isolated at break times and began to look much happier. Mina was able to hold lively ‘conversations’ with Alice by means of writing her replies and remained in regular contact.

Then careful thought was given to the question of ‘work experience’ and the school staff were able to arrange placement at a nursery. After a few weeks Mina began to talk to the nursery children and then the staff. It was during this period that she also began speaking to Alice and the school mentor.

The compulsory oral elements of public exams in both English and French were the next big hurdles, but the school came up with the idea that it would be helpful for the ‘circle of friends’ to be present in the exam room. This was allowed and Mina spoke audibly and passed.

This was a successful but slow programme of support and hard work for all concerned. It had taken two and a half years to get from silence to confident speech. However, the value can be seen in the fact that transfer to Sixth Form College went smoothly and Mina then progressed to university where she is now studying her chosen subject.

It is a measure of the school’s involvement and understanding that a decision was taken to award Mina a special prize for having overcome her fear of talking.

The story from Mina’s point of view in her own words

It’s been five years since I fully overcame SM. I am now 21 and currently doing a university degree. I am happy, talkative and my confidence has increased throughout the years. It all started back in nursery. I don’t know exactly how it started. Was it because someone had said something to me? It all remains a mystery.

At home, I was like any other child – laughing, playing with my toys, watching kids’ programmes and talking to my family – but at nursery, I was a completely different person. I wasn’t able to socialize, talk, laugh. I was constantly anxious, and my face and body language were expressionless. This was due to my social anxiety disorder SM. It was not because I didn’t want to talk. I really did want to talk and make friends, smile and laugh, but anxiety took over, which prevented me from being myself. I was not only anxious at nursery, but outside my home wherever I went, such as shops or my cousins’ houses. The list can go on.

I felt like an alien whenever I walked into a classroom. There was always someone who would either say something about me or whisper something about me during class. Some people would even come up to me and ask why I didn’t talk. It made me feel anxious and I hated myself when people came up to me and asked why I didn’t talk. I felt anxious and self-conscious and I hated myself for it. I hated the fact that I was afraid to speak. I hated the fact that I was unable to stand up for myself. Most nights I went to bed crying because it seemed as if SM was taking over my life. Even talking to my grandmother and some of my aunties and uncles was impossible.

The three words that irritated me the most were ‘She can’t talk’. I used to hear this almost every day at school. I wanted to say ‘I can talk’, but unfortunately I was unable to due to my severe anxiety. I used to ask myself every day, ‘Why me?’ ‘Why does this happen to me?’ I blamed myself because it was my fault that I didn’t talk. It was my fault that I was getting bullied. Everything was my fault. But now looking back, I realize it wasn’t my fault as I couldn’t help the way I was. In an unusual way, I’m glad I had SM, as it has transformed me into a wiser person and it has made me believe that nothing is impossible if you put your mind into it. It has also taught me to never judge someone, as you don’t know what happens behind closed doors.

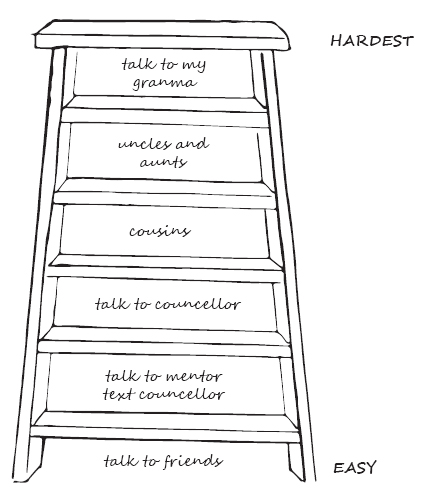

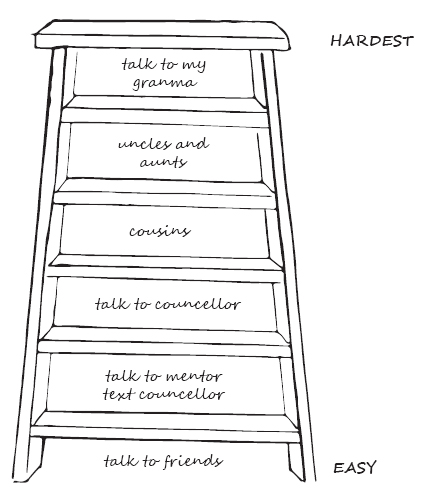

My friends and family, especially my father, supported me and understood my anxiety. There was also the SMIRA counsellor, Alice, who helped me overcome my anxiety. She was very helpful and gave great advice and techniques. The technique that helped me most was setting realistic targets from easiest to hardest. It was like stepping up a ladder every time I accomplished each target, the ladder to success (Figure 16.1).

Figure 16.1 The ladder to success

Also, knowing that there were other people out there with SM made me feel less of an alien. I was not the only person in the world with this disorder. Reading inspirational stories about others overcoming SM motivated me into overcoming my anxiety. Even though not everyone believed that I would overcome it, I had faith in myself that I would, no matter how long it would take. In contrast to my outer appearance – timid, anxious and shy – there was strength, faith and motivation on the inside.

Advice I would give to people who suffer from SM is: never give up, because you will overcome it, however long it takes. It can take months, or even years, but you WILL overcome it.

Remind yourself that you are not the only one going through this, and that, when you accomplish each target – no matter how small – it is a step closer to success. Believe in yourself, have faith and, though this may be easier said than done, try your best not to let other people’s comments bring you down. If they have a problem, it’s theirs, not yours. You are you and if anyone decides to judge you then they are not worthy of your time.

Don’t ever lose hope. You can beat SM.