Sikhs owe their spirit of compassion to the Khalsa.

The inspiration for my learning came from the Khalsa.

Our enemies were vanquished by the steadfastness of the Khalsa.

Is it possible that at some point an inner voice might have warned Ranjit Singh that the end of his wondrous life was near? If it did, it seems to have had no effect on him. Seeing the pace he kept until the very end, it is unlikely he would have paid attention to any premonitions. He had already seen off afflictions that might have felled the hardiest. His brush with death from smallpox at the age of six, leaving him scarred and blind in one eye, had not affected his dynamism. He was stricken once more in 1806 by an undiag-nosed illness and again in 1826 with a far more serious one which involved a paralytic stroke. But in less than five years of the latter, his excesses notwithstanding, he was fit enough at fifty to participate, during the ceremonial occasion with Lord Bentinck at Ropar in 1831, in strenuous events such as horsemanship and tent-pegging.

In 1834, at the age of fifty-four, he had another stroke even more serious than the earlier one. But he would not be deterred – perhaps because the most momentous years of his life always seemed to lie ahead of him. Of these, the year 1837 was one of the more significant because of several events that took place – some good and some bad. The first highpoint of that year was the wedding of his favourite grandson Nau Nihal Singh, son of his heir Kanwar Kharak Singh, in March at Amritsar, the celebration of which has already been described. Shortly after this event came a second highpoint, the repulse of a determined Afghan effort to take back Jamrud Fort from the Sikhs – even though the Sikh forces were outnumbered – thanks to the brilliant leadership of Hari Singh Nalwa. But this triumph, by which Jamrud looked to be well fortified against future aggressors, also brought a cruel blow for Ranjit, with the loss of his dear childhood friend Nalwa on the battlefield. Not only had the two known each other all their lives, they had fought against great odds, side by side, in countless battles. The Maharaja ranked Nalwa as one of his most dependable generals, and when news of his death reached him he first sent a contingent which included Prince Kharak Singh and other notables but unable to stay behind rode out himself – a gruelling ride of several hundred miles – to be present at the site of his friend’s death.

Six months after Hari Singh’s death in April 1837 Ranjit Singh’s other great friend Fateh Singh, Sardar of Ahluwalia, died of high fever at Kapurthala. He and Ranjit Singh had formed a formal alliance in 1802 to underscore their friendship and mutual regard for each other. They had exchanged turbans, a practice confined to very special relationships among Sikhs. Fateh Singh had been with Ranjit Singh on his cis-Sutlej expeditions in 1806 and 1807 and had also taken part in the Bhimbar, Bahawalpur, Multan and Mankera campaigns.

Ups and downs between the two had ended in a cemented relationship. In 1825, told that Fateh Singh was building a fort at Kapurthala, Ranjit Singh had summoned him to Lahore for an explanation. Fateh Singh, innocent of the charge but fearing his lands might be confiscated, had fled to the British for help and protection, and on hearing this the Maharaja had sent Faqir Aziz-ud-din to annex the Ahluwalia territories. However, through British intervention matters were settled between the two, and while lands in the Jullundar Doab remained with Fateh Singh those west of the Beas were acquired by the Lahore Durbar. Ranjit Singh then invited Fateh Singh to return, and the mistrust was put aside. Fateh Singh’s bravery and diligence in a number of their joint ventures was publicly acknowledged, and Ranjit Singh was fond of telling his officers that there was no difference between him and the Ahluwalia chief and that the latter’s orders should be obeyed along with his own.1 Fateh Singh’s death hit Ranjit Singh as hard as his other friend’s had done a few months earlier.

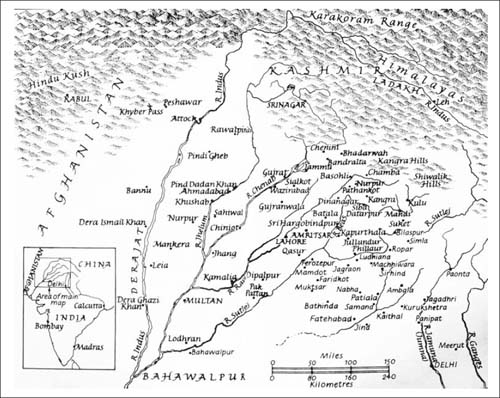

THE SIKH EMPIRE IN 1839, WITH CIS-SUTLEJ TOWNS

Ranjit Singh experienced a third stroke in 1838 during Governor-General Lord Auckland’s visit to Lahore. It was attributed to his robust drinking during the occasion, which came on top of the toll taken by the quantity and strength of his favourite liquor imbibed over the years.

All indications are that Ranjit Singh’s inner voice finally appeared to have convinced him around 20 June 1839 that the end was near. He confided his concern to his foreign minister Fakir Aziz-ud-din, to whom he also conveyed his wish that Kharak Singh should succeed him, with the Dogra Dhian Singh as his prime minister. On 21 June he ordered all his superior officers, European and Indian, to be assembled in his presence and take the oath of allegiance to the heir apparent, his son Kanwar Kharak Singh; this ensured that, contrary to general expectation, he succeeded smoothly and without opposition to his father’s throne.2 The following day Ranjit Singh became unconscious but rallied and went for a short outing in his litter, always available for such occasions. A British medic, Dr Steele, came from Ludhiana to treat him, but nothing much could be done. On 23 June he again went out early in the morning to the Baradari Gardens, but after giving detailed instructions about the dispensing of charities he again became unconscious – after four hours or so to be his usual self again.

His condition became increasingly serious over the next two days, and on 26 June, sensing that his time had finally come, he had passages from the Granth Sahib recited to him as he bowed deeply before the holy book. He then asked that the Koh-i-noor diamond be donated to the Hindu temple of Jagannathpuri in Orissa on the Bay of Bengal. Surprisingly, the Dogra Dhian Singh who was not in favour of the wish told Ranjit Singh that Prince Kharak Singh should be put in charge of doing this. The Koh-i-noor was sent for, but after a lot of excuses the dying ruler was told that it was in the Amritsar treasury. Dhian Singh’s view was supported by the Sardars, to whom possession of the diamond signified the independence of the Sikh kingdom; it was after all a favourite saying of the Maharaja’s that whoever owned it would be the ruler of the Punjab.3 If this last wish of Ranjit Singh’s had been carried out the Koh-i-noor would still be in India and not a possession of the British crown. During the last few days of his life Ranjit Singh gave away large amounts of cash and sundry items to a number of charities. His gifts ranged from richly caparisoned elephants, horses and cows to jewellery, gems, gold vessels and his personal weapons.

There is a moving account of Ranjit Singh’s last hours by C.H. Payne. Although he had managed to recover from yet another stroke, he had lost the power of speech, ‘and a curious and interesting sight it was now to behold the fast dying monarch, his mind still alive; still by signs giving his orders; still receiving reports; and, assisted by the faithful Fakeer Azeezoodin, almost as usual attending to affairs of state. By a slight turn of his hand to the south, he would inquire the news from the British secretary; by a similar turn to the west, he would demand tidings from the invading army; and most anxious was he for intelligence from the Afghan quarter.’4 Clearly, the Lion was still the supreme arbiter of his natural habitat.

The end came on 27 June at five in the afternoon. As the cortège made its way through the capital to the cremation ground, the grief and lamentations of the crowds left no one in any doubt as to what Ranjit Singh had meant to them. He was the personification of a ruler who had earned the respect and love of many of his subjects, not through intimidation or the arrogance of power but by earning their goodwill through his unending concern for them, in which he never faltered. Prayers were said for him by all communities; his subjects knew that at no other time had people of all religious faiths had the liberty to live their lives according to their beliefs, and their grief was truly heartfelt.

The culmination of this day of great emotional upheavals came when four of Ranjit Singh’s wives and seven maids burnt themselves on the funeral pyre. His wife Rani Guddan, daughter of Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra, placed his head in her lap as the flame was applied to the sandalwood bier. Sati was not the custom among Sikh women, and the only previous exception known had occurred in 1805, in the town of Booreeah, on the death of the chief Rae Singh, when his widow had rejected a handsome provision in land, preferring a voluntary sacrifice of herself.5 On 30 June the ashes of the Lion of the Punjab were placed in jewelled urns and taken in a state procession via Amritsar to Hardwar, where some were immersed in the River Ganges and then the rest were taken to Lahore to be placed in a samadhi or mausoleum to this great ruler which was built next to the fort – a place he had loved and the seat of his power.

His final resting place is very near to the samadhi of Guru Arjan Dev, which Ranjit Singh had built with deep veneration for the fifth Guru. As was customary, the architectural form of his own samadhi was influenced by the Hindu and Islamic forms prevalent in those times. The material used was red sandstone in the main structure, with very little marble. Under the central vault and beneath a carved canopy of marble is the symbolic urn also in marble beneath which Ranjit Singh’s ashes lie. There are several stone and marble memorials beneath this vault to commemorate his wives and maids who immolated themselves on his pyre. In the increasing chaos which overtook the realm, the Durbar’s functionaries found little time to assemble the most sensitive designers and craftsmen to design a truly memorable memorial for one of the most exceptional men of the age.

Ten years later Joseph Cunningham was to sum up what he had stood for from the age of ten onwards. ‘Ranjit Singh found the Punjab a waning confederacy, a prey to the factions of its chiefs, pressed by the Afghans and the Marathas, and ready to submit to English supremacy. He consolidated the numerous petty states into a kingdom, he wrested from Kabul the fairest of its provinces, and he gave the potent English no cause for interference. He found the military array of his country a mass of horsemen, brave indeed, but ignorant of war as an art, and he left it mustering fifty thousand disciplined soldiers, fifty thousand well-armed yeomanry and militia, and more than three hundred pieces of cannon for the field.’6

Ranjit Singh attributed his own achievements to the grace of the Sikh scriptures. This acknowledgement of the wisdom of the Gurus and his unquestioning acceptance of the authority of the Granth Sahib were in many ways a radical departure from the prevailing practice of his time – and indeed long before it. In other countries, particularly Western, in any conflict between the monarch and the church, even senior members of the clergy were often overruled in favour of the monarchical view. In marked contrast to this, the absolute ruler of the Sikh state had once accepted a sentence of public lashing pronounced by the Golden Temple’s clergy for a transgression it had viewed with disfavour even if the sentence was never carried out.

It is all the more surprising, therefore, that given the extent of his reverence for the tenets of Sikhism Ranjit Singh openly flouted one of them by setting himself up as a monarch with absolute authority over the affairs of the state and over all Sikhs resident in it. He thereby ignored the republican tradition which Guru Gobind Singh had established.

The tenth Guru had left no room for any ambiguity regarding the republican underpinnings of the Sikh religion. ‘Wherever there are five Sikhs assembled who abide by the Guru’s teachings,’ he had told his followers, ‘know that I am in the midst of them … Read the history of your Gurus from the time of Guru Nanak. Henceforth the Guru shall be the Khalsa and the Khalsa the Guru. I have infused my mental and bodily spirit into the Granth Sahib and the Khalsa.’7 Another verse by him conveys this message:

The Khalsa is a reflection of my form,

The Khalsa is my body and soul,

The Khalsa is my very life.

Ranjit Singh made the grievous mistake of ignoring the essential meaning of these words, which unequivocally spell out the purpose of the Khalsa and that its goals should be reached through the collective will of its constituents. For each member of the Khalsa to survive and fulfil the aim of his life, he had to view his fellow religionists as representing the Gurus – and in particular the tenth Guru, Gobind Singh, who had founded the Khalsa – as his ‘form’, as his ‘body and soul’, as his ‘very life’. To try to dominate the Khalsa was tantamount to trying to dominate the Guru. Decisions had to be arrived at by members of the Sikh faith, collectively and by mutual consent, not by diktat.

Monarchs, since they are by definition sole and absolute rulers, are anathema to the ideals of a faith – like the Sikh – which requires equal representation in all major decisions. For such decisions a large gathering of the Sikhs – a Sarbat Khalsa – would pass a gurmatta or a collective resolution on the course to be taken. This is what was done in 1760 and 1765 when the Khalsa assembled at the Durbar Sahib to decide on annexing Lahore from the Afghans. The panj piyare, the five chosen ones, could also take decisions on behalf of the panth, the Sikh community.

Even though he held these guiding principles of Sikh beliefs in high regard, Ranjit Singh failed to foresee the disastrous consequences his monarchy would have on the Sikh state. He had, obviously, hoped that his successors would be as skilful as he in warfare, statesmanship and general qualities of leadership and would ensure the continuity and growth of the Sikh empire he had built with such confidence and skill. This was not to be. But he also ignored the fact that ‘it is the self-respect, the awareness of his own ultimate significance in the creation of God, which imparts to a Sikh of Guru Gobind that Olympian air and independence which fits ill with a totalitarian or autocratic monarchical system of organization of power’.8

In his well-researched book Parasaraprasna, the Sikh scholar Kapur Singh, in a chapter ‘How a “Sikh” Is Knighted a “Singh”‘, graphically recreates the momentous events which took place at Anandpur Sahib on 30 March 1699, when Guru Gobind Singh created the Khalsa and provided a new dynamic for a fledgeling faith. One of the cardinal conditions underscored for observance by all new entrants into the Khalsa was that its members must henceforth clear their minds of all previous traits, beliefs, superstitions, loyalties and such and believe solely and exclusively in one formless and unchanging god who dwells in each human being.

’Your previous race, name, genealogy, country, religion, customs and beliefs, your subconscious memories and pre-natal endowments, samskaras, and your personality-traits have today been burnt up and annihilated. Believe it to be so, without a doubt and with the whole of your heart. You have become the Khalsa, a sovereign man today, owing allegiance to no earthly person, or power. One God Almighty, the Timeless, is the only sovereign to whom you owe allegiance.’9

How deeply this idea is ingrained in the minds of Sikhs can be judged by the degree to which they have always asserted themselves in whatever task they have undertaken, whether on the battlefield, in occupations requiring a tough physique such as agriculture or, more recently in industry, transport and much else. So it is not difficult to understand why the monarchical idea thrust on them did not succeed after Ranjit Singh’s death and why, when the monarchy collapsed, it brought down with it everything he had built with such flair and faith in his own sense of destiny.

The Gurus had underscored the importance of giving practical form and substance to an idea, not leaving it as an idea in the abstract. That is how Sikhism became a live and vibrant reality. They wanted every Sikh to have a practical bent. In this context Ranjit Singh’s contribution was the specific form he gave to a commonwealth of the Sikhs. Before him the misls and other groups of Sikhs had more often than not been in conflict with each other. He forged them all together and gave them a sense of pride and power because of the inspiration they received from their religious beliefs.

The resilience and ruggedness of the Sikh faith and its followers, and their resolve and spirit of independence, were and are continuously nurtured by the Guru Granth Sahib and its evocative, balanced, rational and realistic view of life. It has sustained the Sikhs in the past and will continue to do so in the future. Not long after Ranjit Singh’s death even the British acknowledged the quality of principled self-confidence he saw in them. In a letter to Ellenborough, Henry Hardinge, his successor as governor-general, wrote: ‘The Sikh soldiers are the finest men I have seen in Asia, bold and daring republicans.’ His letter is dated 19 March 1846 – less than three years before the end came for the Sikh empire.

Ranjit Singh achieved his goals because of his uncanny understanding of how to handle the Khalsa’s sense of pride and independence and how to motivate each individual to strive for his goals whatever the odds. His iron will inspired his men, held them together and brought out the best in them. He needed men of talent and experience in his government, and because Sikhs accounted for a very small percentage of Punjab’s population he had no hesitation in bringing in anyone of merit, whatever his background or faith, to serve the state. He was confident that in the final count he could control them. In the execution of this policy, however, he allowed a split to open up between the phenomenal achievements of his lifetime and his inability to ensure continuity after his death.

After extending Punjab’s borders into far-away lands, breaking the Afghan stranglehold on India and knitting together the many culturally diverse religious, ethnic and linguistic groups in his realm, Ranjit Singh diluted the sustainability of what he had created. Had the hill Dogras Dhian Singh and Gulab Singh – whom he raised ‘almost from the gutter’, as Kapur Singh puts it, to the highest positions in his realm – been the only ones of their ilk, Ranjit Singh’s legacy might conceivably have survived. But there were others whose true capacities for bringing down the edifice their sovereign had built were revealed only after his death, and among these the two that stand out are Tej Singh, an ‘insignificant Brahmin of the Gangetic-Doab’, in Kapur Singh’s words, and another Brahmin, Lal Singh; after Ranjit Singh’s death the last two were promoted to the top commands of the Sikh army.

To suggest that Ranjit Singh was not a good judge of men is unfair to him. He made sure that the men he chose from different faiths, beliefs and persuasions served him well. His personality and iron will ensured that his writ would prevail throughout his empire, no matter how far the territories of the Sikh state extended, and seldom in his lifetime did anyone have the courage to cross his path.

Although the terms ‘kingdom’ and ‘empire’ have been used freely throughout this book they jar with the republican ideal of the Sikh faith. Guru Gobind Singh, foreseeing the pull that India’s feudal traditions, nurtured further by its caste system, would exert on Indian minds conditioned to accept hierarchies, emphasized his idea of an ‘aristocracy’. It could not be by right of birth. ‘Such an aristocracy [had to be] dedicated and consciously trained … an aristocracy … grounded in virtue, in talent and in the self-imposed code of service and sacrifice, an aristocracy of such men should group themselves into the Order of the Khalsa.’10 The translator of Guru Gobind Singh’s concept of ‘an aristocracy’ appears to have used this word unwittingly, whereas meritocracy is what Guru Gobind Singh always emphasized as the ideal of the Khalsa. The same ideal was to prove central to secularism, too.

Ranjit Singh did in fact follow the injunction of Guru Gobind Singh by creating a meritocracy based on virtue and talent and dedication. However, the distinction between an aristocracy defined not by ‘right of birth’ but by its ‘self-imposed code of service and sacrifice’ is soon lost when upstarts with unearned titles of princes and such usurp the rights of those who have virtue and talent but are humble by birth. This is precisely what happened after Ranjit Singh’s death, and it is not surprising that the Khalsa started to revolt:

The Khalsa is never a satellite to another power,

they are either fully sovereign or

in a state of war and rebellion.

A subservient coexistence they never accept.

To be fully sovereign and autonomous is

their first and last demand.11

The truth of this became evident within months of Ranjit Singh’s death. When his sons and their wives, nephews and senior functionaries of the Durbar vengefully turned against each other, the army, too, was inevitably, and irresponsibly, drawn into political decision-making. ‘Such a right is not inherent in the concept of the Khalsa,’ as one of the present authors has written elsewhere. ‘Furthermore, whilst Ranjit Singh’s leadership qualities had kept the army in line, its restiveness against his weak successors was now evident and when it spilt over, a major shift occurred from the political system created by the Gurus, in which rights had been invested in the entire Khalsa community, and not just the army. The manner of the army’s assertiveness, though not directed at the state, damaged the state’s cohesiveness since it lacked the discipline with which the Khalsa had closed its ranks against all adversaries in the past. This time it was divided both against itself and against others; an antithesis to the concept of a united Khalsa.’12

The qualities of spirituality, self-discipline and unlimited self-confidence which the Khalsa had introduced into the Indian mosaic were fatally subverted at this time, a process aided and abetted by the elites of India’s older religious faiths, led by Hinduism and Islam, which had always at heart resented the vigorous self-assertiveness of the Sikhs. The end result was the weakening of the great legacy of the Khalsa’s founding principles, of a magnificent and unprecedented state. This was the ultimate price paid for Ranjit Singh’s error of judgement in departing from a key founding principle of his religion and creating a monarchy, even though he never behaved like most despotic monarchs have done through the ages.

Monarchical rule had been habitual during the most significant periods in Indian history, whether Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, Mughal or British. The fountainhead of power was the sovereign, not the people. If the people were restless, the rulers knew how to repress them. Those who were benign and ruled justly did so out of inner convictions, not because they were compelled to by the tenets of their faith. The emergence of the Sikh faith, committed to the republican democratic tradition, was a rare event in an environment in which authority was exercised arbitrarily and decisions in statecraft were whimsical more often than wise.

Another point to note is that whilst all great religions have waged wars against each other in attempts to establish their primacy, the Sikhs never fought wars to establish the supremacy of their faith. Their wars were fought to restore the sovereignty of their country, not the right of their religion to dominate people of other denominations. Ranjit Singh’s critics, who rightfully criticize his monarchical bent, give him little or no credit for the even-handedness with which he applied the secular principle to the Sikh state. This quality of the man stood out in barbaric times. If the Sikh faith still has vitality and vigour, despite the setbacks it suffered as a consequence of his mis-step in establishing a monarchy, it is because the Gurus, unlike Ranjit Singh’s critics, took into account human foibles and frailties.