Today, in most schools, the “effectiveness” of teachers is measured by their students’ performance on annual state tests. Because of the importance placed on these test results, teachers walk into their classrooms every day focused on preparing their students for the standardized exams that will arrive in the spring (one school I visited this year had a “Countdown to Test Day” poster hung in the entranceway to the school—”34 More Days Until We Dominate on the State Tests!”). Unfortunately, when we focus on preparing students for distant standardized tests, three key problems ensue: (1) Preparing students for a standardized reading test is fruitless, because there is no such thing as a standardized reading test; (2) Standardized testing leads to a narrowing of the curriculum; and (3) Standardized testing leads to the creation of standardized students.

Let’s take a closer look at these three issues.

Hirsch and Pondiscio (2010–2011) argue that there is no such thing as a standardized reading test, because the tests we give our students to measure their ability to read are really not testing their ability to read. Instead, these tests really measure the depth (or lack of depth) of our students’ background knowledge. Here’s an example:

If a baseball fan reads “A-Rod hit into a 6–4-3 double play to end the game,” he needs not another word to understand that the New York Yankees lost when Alex Rodriguez came up to bat with a man on first base and one out and then hit a ground ball to the shortstop, who threw to the second baseman, who relayed to first in time to catch Rodriguez for the final out. If you’ve never heard of A-Rod or a 6–4-3 double play and cannot reconstruct the game situation in your mind’s eye, you are not a poor reader. You merely lack the domain-specific vocabulary and knowledge of baseball needed to fill in the gaps. Even simple texts, like those on reading tests, are riddled with gaps—domain knowledge and vocabulary that the writer assumes the reader knows. (2010-2011, 50)

Students who know baseball would score well in responding to the A-Rod sentence; students who do not know baseball at all would struggle with it. Because there are thirty-five very diverse students sitting in my third-period class, there is no single test devised that accurately assesses their reading abilities without putting some of them at a distinct disadvantage. Any given test will value the background knowledge of some students while disregarding the background knowledge of others. Our children’s reading ability is tested without regard to whether they possess the requisite background knowledge.

To get a sense of how national tests drive the bus, let’s look back at what happened in our schools when NCLB was the flavor du jour. The following findings are cited in Yong Zhao’s World Class Learners:

• Five years after the implementation of NCLB, “over 60% of school districts reported they had increased instructional time for math and English language arts, while 44% reported they had reduced time for other subjects or activities such as social science, science, art and music, physical education, and lunch and/or recess” (Zhao 2012, 38). This amounted to a 32% decrease in the teaching of these subjects. This decrease, of course, had an adverse effect on young readers, as they have to know stuff to read stuff. The less a student knows about history, science, art, and music, the narrower his or her prior knowledge will be.

• A second level of curriculum narrowing occurred within the math and English language arts classes, where most districts narrowed the curricula to what was covered on the state tests (Zhao 2012).

• “Instructional quality and opportunities to access a diverse curriculum deteriorated. Cognitively complex teaching became more basic-skill orientated and students became ultimately less cognitively nimble.” (Zhao 2012, 40)

Clearly, the testing that coincided with NCLB narrowed the curriculum, and in doing so, it also narrowed our students’ thinking. And now a new round of tests have arrived—those designed to measure implementation of the CCSS and of other standards newly adopted by outlier states—and once again it is troubling to consider how these exams are influencing our classrooms. As I write this, for example, I am teaching in New York and our students recently participated in the inaugural administration of CCSS-aligned high-stakes state exams. The students were given reading passages over three days—passages that leaned heavily toward nonfiction, with very little poetry mixed in. Close reading was heavily emphasized.

Because their “effectiveness” is measured by their students’ performance on these exams, it is not hard to predict how the new exams will change how teachers teach. Nonfiction will be disproportionately ramped up, fiction and poetry will be deemphasized, and students will be given a lot of choppy, unconnected close reading practice. As a result, the new tests will narrow the reading curriculum and instruction in a way that is not in the best interest of our children.

Another problem inherent in herding all students toward the same standardized test is that we end up leveling our students to the (often rather low) bar set by the tests. Do we really want to create a generation of “standardized” students? As Tom Newkirk notes in Holding On to Good Ideas in a Time of Bad Ones:

A rationalized, consistent, centralized, uniform system of instruction is incredibly attractive. These systems allow administrators to speak with confidence about the education process and its product. Standardization and standards seem so linguistically close that one shades into another. It may be that there is something aesthetically pleasing in uniform action—the pleasure of watching a drill team, for example. Yet, standardization only leads to sameness, not necessarily quality, and rarely to excellence. (2009, 8–9)

Newkirk is right: Standardization rarely leads to excellence. When the curriculum is narrowed into a sameness, when we adopt a “one size fits all” approach, creativity suffers and students whose talents are not valued by the tests risk being marginalized. At a time of globalization—when it is crucial that we nurture creativity and intellectual risk taking in our students—this latest round of tests is having the opposite effect by standardizing our students. Instead of “racing to the top,” our students are travelling in herds.

When I first proposed the idea for this book, I half-jokingly suggested Calm Down as the working title (actually, I had added a couple more words in this proposed title, but we’ll keep it clean here). I had suggested this as a title because of the level of stress teachers are under. When you consider how daunting it is to teach thirty-six anchor language arts standards (ten reading standards, ten writing standards, six listening and speaking standards, and six standards in language conventions) to a classroom of adolescents, is it any wonder that in some schools the teacher dropout rate is actually higher than the student dropout rate (Kain 2011)? I can’t think of another time in my thirty years in the classroom where teaching was as stressful as it is now.

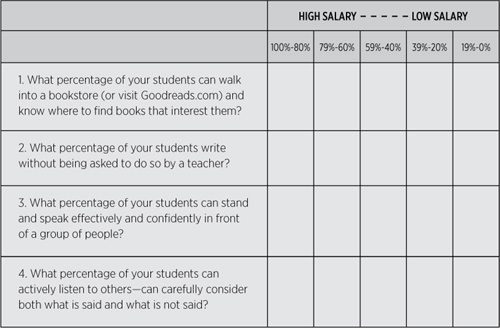

It doesn’t have to be this hard. Allow me to suggest a much simpler approach to measuring a teacher’s effectiveness. Imagine teaching in a school where all this overtesting has been thrown out the window—a place where a teacher’s effectiveness is instead evaluated on four simple criteria:

1. What percentage of your students can walk into a bookstore (or visit Goodreads. com) and know where to find books that interest them?

2. What percentage of your students write without being asked to do so by a teacher?

3. What percentage of your students can stand and speak effectively and confidently in front of a group of people?

4. What percentage of your students can actively listen to others—can carefully consider both what is said and what is not said?

Imagine these four questions forming the rubric that is used to measure a teacher’s effectiveness, and thus, to determine a teacher’s salary. The rubric might look like this:

Ridiculous, right? Perhaps. But let’s pause for a moment and think about how the teaching would change if this rubric were a reality. Let’s look at just one of these questions—What percentage of your students can walk into a bookstore (or visit Goodreads.com) and know where to find books that interest them?—and let’s explore how a question as simple as this would change how reading is taught.

If a teacher’s salary was dependent on the percentage of students who could find interesting books on their own, my bet is that the teacher’s approach would immediately change. How, specifically, would things change? Extensive libraries would be immediately built in every classroom, and as a result, students would have access to a lot more high-interest books. There would be a lot more choice when it came to what students read, and students would be given say in planning and mapping out their reading journeys through the school year. Book talks and book sharing would become a central tenet in all ELA classrooms, and students would discover authors they would have otherwise never encountered. Book club reading would gain higher prominence, and students who were exposed to books they liked would abandon the fake reading practices they have become so expert in. Students would be placed on the pathway to being lifelong readers.

It is also worth noting what would be removed from our classrooms should this question become the criteria for judging a teacher’s effectiveness. Gone would be the worksheets. Gone would be the test prep. Gone would be the ten-week unit where students overanalyze a book to the point of readicide. Gone would be the bubbling in of multiple-choice quizzes and exams. Gone would be the boredom that is generated when all of these numbing teaching practices converge on fragile, reluctant readers.

I can hear the questions being directed to me as you read this: Is this a call for the abandonment of whole-class novels? Will teachers no longer be able to decide what students should read? Will I no longer be able to teach To Kill a Mockingbird? To answer these questions—and more—it might be helpful for us to revisit a proposal I made in Readicide; doing so will better explain the new shift that I am about to advocate in this chapter.

We are living in a time of shifts in education. A focus on NCLB requirements has shifted to the CCSS (or other standards). Classrooms with less diversity are shifting into becoming classrooms with more diversity. Whole-class, blanket instruction is shifting to differentiated instruction. Professional development is shifting from traditional workshops to virtual learning and to social media. Traditional books are being replaced by e-readers. In the face of all this shifting, it is only natural to wonder: How much shift is occurring in the teaching of reading in the middle and high school?

To get a sense of this, let’s return to the shift I advocated in Readicide—the 50/50 Approach—which called for half the reading done in school to be recreational in nature (Gallagher 2009, 117). In the chart that follows, you will find the ten recommendations made in the 50/50 Approach. Next to these recommendations is a scorecard indicating whether these shifts have indeed occurred in our schools.

Of these ten recommendations, seven of them are generally not happening; three of them are spotty at best. In other words, in an age of great shifts in education, very little has shifted when it comes to the teaching of adolescent readers. The teaching of reading remains stuck in a paradigm that doesn’t work, and when students are stuck in a paradigm that doesn’t work, there are dire consequences:

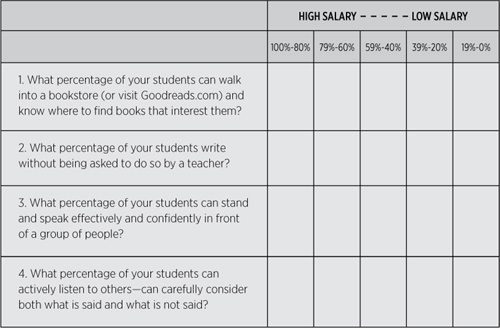

• Here are SAT reading scores since 2002, the year No Child Left Behind was implemented:

Source: National Center for Education Statistics 2013a

• The 2012 and the 2013 SAT reading scores are the lowest scores in thirty years.

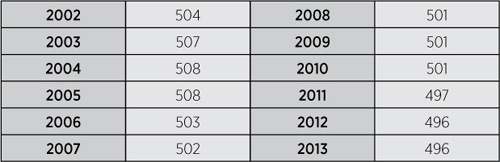

• Many of our college-bound students are not ready for postsecondary studies, even those heading to our most selective universities (see Figure 8.1). At the community college level, as many as 60 percent of students are not prepared for the academic demands that await them.

Figure 8.1 The readiness gap (National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education/SREB 2010)

• One study I cited in Readicide found that there is a “calamitous, universal falling off of reading that occurs around the age of 13” (112). Now, seven years after that study was published, little appears to have changed. According to new statistics released by the Labor Department, teenagers between the ages of fifteen and nineteen are down to reading only four minutes a day (Kurtzleben 2014). This year I have fewer dedicated book readers amongst my students than I have ever had in my thirty-year teaching career. Figure 8.2 shows that, generally speaking, the younger one is, the less likely that he or she is reading very much.

Let’s recap: We are seeing the worst SAT scores in thirty years. A large percentage of students now enter college unprepared for the reading (and other) demands placed upon them. We are seeing fewer dedicated book readers and a continued fall in the amount of time spent reading. And a new set of reading standards that continue to narrow our students’ reading experiences have been thrust upon us.

Figure 8.2 Reading by age group (Kurtzleben 2014)

All of this adds up to the need for us to shift our thinking once again.

In considering where schools have gone wrong in building lifelong readers—and how this may help us to rethink our approach to teaching reading—we should start by looking at what kids are being asked to read in our classrooms. In most secondary schools I have visited, there is only one kind of reading going on: hard reading. Students spend a number of weeks dissecting Hamlet before moving on to wrestle with Beowulf before grappling with whatever core work is lined up next. When students finish “wrestling” with one hard text, another is thrust in front of them. I put “wrestling” in quotation marks because, in reality, many of the students are not actually reading. They are skimming and listening carefully in class. Very little wrestling of difficult text is actually occurring. Worse, many students—including those in our honors classes—are proud that they don’t actually need to read the books. The “one hard book after another” approach, which, again, is predominant, is fertile ground for creating students who fake-read. It is a recipe for killing readers.

Paradoxically, I see another kind of reading going on in schools: reading that is too easy. On my campus, for example, we have a daily, twenty-four-minute, campus-wide reading block during which students are encouraged to self-select books to read recreationally. And what happens when we ask reluctant readers to choose reading material? They often pick the easiest books they can find. This is why I have high school students who read at grade level still spinning their wheels reading A Child Called “It” (Pelzer 1995) or Diary of a Wimpy Kid (Kinney 2007). Reading books that are too easy can have the same deleterious effect on young readers as asking them to read books that are too hard: interest is soon lost and reading becomes a bore.

I have come to believe that most of the reading done in our schools is either too easy or too hard. This is different from the reading that occurs outside the walls of the school building, where most people read somewhere in that zone between “too easy” and “too hard.” This zone is where you and I do most of our reading. And it is in this zone between “too easy” and “too hard” where I propose that most of our students’ reading should be occurring. So how do we move our kids into this new zone of reading?

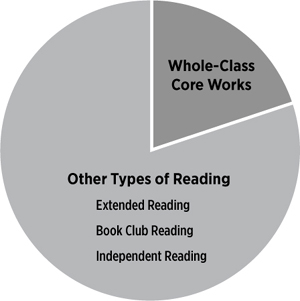

My attempt to move students into the zone of reading between “too easy” and “too hard” begins by replacing the 50/50 Approach I advocated in Readicide with a 20/80 Approach. In short, I am striving for the following kinds of reading for my students (Figure 8.3):

Figure 8.3 The 20/80 Approach

Let’s take a closer look at each section of the 20/80 Approach reading pie.

There is a lot of shifting going on right now around the topic of teaching the whole-class core work. Some people I respect a lot are advocating a severe limiting of, or, in some cases, a complete removal of whole-class core works from the curriculum. Their arguments are many:

• Different students have different interests. One book does not speak to the same thirty students.

• Requiring students to read books that are too hard for them is the central contributing factor in turning kids off to reading.

• Choice is a key motivating factor for young readers. When the teacher chooses the text, motivation suffers.

• Hard reading often shuts down readers and leads to fake reading. “SparkNotes reading” replaces real reading.

• Hard reading often leads to slow reading. If all reading is hard, fluency, and thus, comprehension, will suffer.

• There are tons of worthy books to read. Isn’t it presumptuous of the teacher to decide which one is worthy for all students to read?

• Choosing a classic for students to read perpetuates racism and/or sexism, as most of the canon is made up of dead, white, European, male writers; students need to read more culturally relevant authors and books.

Each of these concerns speak to me, but I remain steadfast in believing that whole-class core work instruction remains an important part (20 percent) of my classroom. Here are my responses to each of the preceding concerns:

Though I agree that my students’ interests are varied, I do believe some works are so rich that they merit a whole-class reading. Hamlet, for example, is one of these works. Its themes cut across time, across cultures, across generations. There is something rich to think about in this play for every one of my students. Hamlet explores some pretty serious and relevant questions: What happens to us when we die? What are the ramifications of your actions (or inactions)? What are the consequences of misogyny? How are nations led to ruin? Is revenge ever worthwhile? Is suicide ever a reasonable option? What happens when we are guided by lust instead of by reason?

All students, not just a select few, should have the opportunity to wrestle with the questions embedded in Hamlet. Some works are grand enough to speak to all. Hamlet is one of them.

First, I have always been a little queasy determining if a book is too hard for my students. Readability formulas are sometimes unreliable and are often affected by so many factors—motivation, genre, prior knowledge, syntax—that I sometimes struggle with telling my students they can only read within a predetermined band. That said, it is clear that there are books that are truly too hard for my students to read on their own, and asking them to do so would amount to, as some have suggested, educational malpractice.

But when I teach a whole-class work, I am not asking my students to read hard works on their own. I am asking them to read them alongside me and alongside their classmates. If the work, like Hamlet, is too hard for them to read independently, then I have to design lessons that help fill the gaps created by their reading deficiencies. When teaching Hamlet to students far below reading level, for example, I give them copies of No Fear Shakespeare (SparkNotes 2003), which translates Shakespearean language into modern language. My goal is not to enable students to be able to decipher 400-year-old language; my goal is that my students understand the play well enough to think deeply about what they’ve read. If need be, I provide some students with professional audio recordings so they can listen along as they read. In addition, I show several different film interpretations of key scenes. When deep confusion continues, we stop and revisit key passages in the text, pausing for students to discuss and to write about their thinking. I don’t assign Hamlet; I teach it.

It is counterintuitive, but I think students—with expert guidance from the teacher—should read a few books (and poems and short texts) that are a bit too hard for them. This is how young readers stretch and grow. There are lines in Hamlet I still do not understand, and I have read the play countless times. Does this mean I never should have attempted to read it?

I agree that students are often demotivated when the teacher selects the text that everyone will read. I can remember the trepidation I felt in high school when Hamlet became my required reading. It was hard and confusing, and I am sure I would have rather read something else. But I love Hamlet today because someone made me read it. This is not a bad thing, as there is a greatness in Hamlet that I needed to “discover”—a greatness I never would have encountered had I not been required to read it. This is my job as a teacher of deep literature—to design lessons so that my students can discover this greatness as well. (My thinking here is not simply about Hamlet. I am using that work as a placeholder for all great works of literature.)

That said, there will always be some students who do not like the whole-class text. This also does not concern me, as my job is not to get every student to like the work; my job is to get every student to recognize the value of reading the text. Not every student will adore Hamlet, but I do want every student to take thinking away from the reading of the play that will make him or her smarter about the world in which we live. Or to take another example, you don’t have to like science fiction to get some value from reading science fiction. Some students don’t like reading 1984, but all who read Orwell’s novel learn to understand propaganda techniques and language manipulation—skills they can apply well beyond high school. There is a lifelong value to studying 1984, even if it is not your favorite book or genre.

Asking kids to read hard books is not the problem. Asking them to read only hard books is the problem. If everything they read is hard, eventually they will shut down or resort to fake reading. But remember, in the approach I am advocating here, hard reading makes up only 20 percent of the reading I want my students to do over the course of the year. Most of the reading I will ask them to do is much more likely to be found in the zone between “too easy” and “too hard.”

And one last thought about “SparkNotes reading”: It does not bother me in the least that my students read SparkNotes. I have read them as well over the years, and I have learned from them. I don’t mind if a student reads the To Kill a Mockingbird SparkNotes while concurrently reading the novel. In fact, reading SparkNotes may help the student to enjoy the novel. This lesson was reinforced to me this year when I went to see a production of Twelfth Night on Broadway. Since I had not read the play in many years, can you guess what I did before attending? That’s right. I went online and read the complete synopsis of the play. This “cheating” did not detract from the play I was to see later that evening; on the contrary, it made my “reading” of the play much better.

The reading of SparkNotes does not bother me; what bothers me is when students read only the SparkNotes. These notes should augment the reading of major literary works, not replace the reading of them.

Slow reading is an important skill to cultivate, especially in an age when students are doing a lot of “click and go” reading. All of the scanning and skimming while reading digitally has cognitive neuroscientists worried that humans “seem to be developing digital brains with new circuits for skimming through the torrent of information online. This alternative way of reading is competing with traditional deep reading circuitry developed over several millennia” (Rosenwald 2014).

Maryanne Wolf, a Tufts University cognitive neuroscientist and the author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, worries “that the superficial way we read during the day is affecting us when we have to read with more in-depth processing” (Rosenwald 2014). Wolf warns of an “eye byte” reading culture where students risk losing the ability to read deeply, and she suggests that educators work hard to cultivate “biliterate” reading brains—brains that can scan and skim as well as read slowly and deeply over extended periods of time. This second skill set—the ability to read slowly and deeply over extended periods of time—is only developed one way: by having students read slowly and deeply over extended periods of time. There are no shortcuts to developing that skill set. Hard reading is the place where the deeper half of the biliterate brain is developed, and the vast majority of my students—most of whom spend most of their reading lives skimming and scanning—need more practice reading cognitively challenging, extended texts.

I am not concerned that the kind of slow, deep reading I am advocating here will have deleterious effects on my students’ overall reading fluency. In fact, I am arguing just the opposite: Students need practice slowing down and really wrestling with text. But it is also important to remember that this kind of deep, slow reading makes up only 20 percent of my students’ proposed reading diet. They will still be reading lots of other kinds of texts at a much brisker pace (more on this later in this chapter). Certainly enough of this other kind of reading will occur so that both their fluency and their comprehension will steadily improve.

If I were a social science teacher teaching an American history class, I certainly would not try to teach every major event in this nation’s history. Doing so would flatten out the curriculum into a coverage approach, and would lead my students into becoming memorizers instead of thinkers. Instead, I would make sure that my students studied in depth specific events that I had selected. For example, I would certainly spend a great deal of time on the Civil War because I believe that students who do not deeply understand the Civil War do not deeply understand American history. I would not leave it to chance that my students would choose the Civil War as a unit of study. On the contrary, an in-depth study of the Civil War would be a nonnegotiable requirement, and I would design a unit that would take all of my students into a deep examination of this seminal event.

Likewise, if I were an art teacher teaching a sculpture class, I would have students study Michelangelo’s David, and we would continue to develop an appreciation of greatness by studying other influential works of sculpture (chosen by me, the teacher). Students would also be given opportunities to branch out and explore other sculptors who they felt were worthy of study, but these explorations would be intertwined with whole-class study of sculptors who had greatly influenced the field.

If I want my students to gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of my content area (in this case, the study of literature), I must select some works that are worthy of whole-class study. Is it presumptuous for me to select which titles are worthy of whole-class attention? Yes, of course! But this is no more presumptuous than the history teacher who selects the Civil War to be studied in depth, or the art teacher who decides that the unit of study will start with Michelangelo’s David and work outward from there. My job is to bring greatness into the classroom and set it in front of the students, and to do this, I have to make a judgment call on what defines “greatness.” Doing so requires me to be presumptuous. In fact, teachers in all content areas are presumptuous, because no teacher can teach everything in his or her content area in one year (or semester). All teachers make serious decisions on what to leave in and what to leave out. All teachers are presumptuous (whether they know it or not).

One last note on this point: I am not advocating that individual teachers be empowered to decide which core books are worthy of whole-class instruction. I have seen too many teachers pick books that are too “light” or, in some cases, books that are inappropriate for the entire class to read. What I am advocating is that members of English departments sit down together and have serious discussions as to what books are worthy of whole-class instruction. These decisions should be team decisions. (For what makes a book worthy of whole-class instruction, read Carol Jago’s With Rigor for All [2011].)

Not all whole-class novels need to emanate from the traditional canon. In my school in California, where my students are predominantly Latino, we studied Rudolfo Anaya’s (1972) Bless Me, Ultima as a whole-class read. In the school where I taught in New York, the students are predominantly African-American, which is one reason they read Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (1994). Again, I would never teach a whole-class novel by any author unless the book was worthy of a deep study, but there are many books outside the traditional canon worthy of whole-class reading.

That said, I am also a proponent of teaching the classics, and there is no denying that a literature class steeped in teaching the classics will favor dead, white, European, male writers. This is another reason why the classics only compose 20 percent of the reading my students will do in a school year. The rest of the reading my students do will give them plenty of opportunity to dive into more culturally relevant authors and books.

The whole-class novel approach discussed in the preceding section still represents reading that is very hard for my students. The goal, however, behind the shift to the 20/80 Approach is to give my students a lot more experience reading in the zone found between “too easy” and “too hard.” This targeted zone comprises three different kinds of reading—extended reading, club reading, and independent reading—which are defined as follows.

“Extended reading” extends a core work and branches students into related readings. If students had just completed 1984, for example, I might put them in groups and suggest one of the following dystopias as their next read. Each group then decides which book it wants to read.

Suggested Extended Reads

Awaken by Katie Kacvinsky (2011)

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak (2006)

Divergent by Veronica Roth (2012)

The Last Book in the Universe by Rodman Philbrick (2000)

Little Brother by Cory Doctorow (2008)

Matched by Ally Condie (2010)

Snow Falling in Spring: Coming of Age in China During the Cultural Revolution by Moying Li (2010)

Escape From Camp 14 by Blaine Harden (2012)

The extended list is suggested: Students have the right to propose other titles they feel would also extend a big idea found in the core work. (For this and other text sets built around core works, search my name at Booksource.com and use “KellyG” as a code to receive a discount. Please note that I do not personally profit from my association with Booksource—all of my proceeds for the sale of these sets are paid in high-interest books, which are then donated to needy schools. I receive no payment.)

In extended reading, students choose what to read, but their choices are limited by the connection to the core work and by the teacher’s recommended reading list (though students can propose other titles).

In club reading, students have choice when it comes to what they will read, but these readings will be done in small-group settings. Here are some central tenets of book club reading:

• Students are grouped. The teacher forms the book club groups after careful consideration of reading abilities and interests, student motivation, gender, and the personalities involved. Students are given some voice in grouping decisions as well, as they are given the opportunity to submit suggested partners (with rationales) to the teacher.

• Choice is the centerpiece. In their book clubs, students choose which books they will read. Sometimes the new selection may extend the reading of the previous selection; other times this is not the case. Often, students are encouraged to pick a book that “pushes back” or counters what they have just read. Sometimes the book chosen is completely disconnected to any previous readings. With these considerations in mind, the students in the small group decide what the next read will be.

• Groups meet regularly. Each group meets three times over the course of reading their book, and those meetings should occur when they have read one-third of the book, when they have read two-thirds of the book, and when they have finished reading the book. These are rough goals, for each group determines its own pacing and due dates. Some students will read faster than required by the due dates. When this happens they are encouraged to revisit and skim the section of reading before the discussion.

• Groups meet over the long haul. The book clubs are not formed until the reading culture of the classroom is established, and this usually does not occur until after the first couple of months of the school year. Once the groups are established, I want students to build reading relationships with one another, which take time to develop. (One disclaimer: occasionally groups may have to be adjusted if a conflict arises that is not readily solvable.)

• There is instruction attached to the book club meetings. Even though students are self-selecting the books to be read, there is still instruction attached to book club meetings. Before each club meeting, a mini-lesson is conducted by the teacher. Some of the lessons may be tied to identifying big ideas in the books. Students might be asked to consider one or more of the following questions: What is worth talking about? What does the author want us to think about? What is a big idea that is hiding in this book? These questions, which can be asked at all three meetings, are designed to encourage students to track their thinking over time, and in doing so, to make them more discerning readers. Other mini-lessons might be designed to enable students to recognize the writer’s craft—to notice the writer’s “moves.” Sometimes light is shined on these moves to help students understand how these moves help readers to uncover the big idea(s). Other times students look at a writer’s moves because doing so leads them to adopt the same moves for their own writing. Recognizing good writing is foundational to creating good writing.

• Student thinking should be made visible. As they read, students capture their thinking in thought logs (composition books), and these logs are brought to each book club meeting to help spur meaningful conversation. Students are also asked to share sentences from the books that exhibit beautiful craft—some of which we will study later as a class.

• Assessment comes in many forms. How does the teacher know if the students are doing their reading and whether or not they are generating meaningful conversations? I recommend the following assessment tools:

Book club notes. The teacher sits in on the students’ club discussions and takes notes, getting a sense of who is deeply contributing to the conversation.

Book club notes. The teacher sits in on the students’ club discussions and takes notes, getting a sense of who is deeply contributing to the conversation.

One-on-one notes. The teacher confers with individual students, again measuring the depth of each student’s participation and thoughtfulness. These conferences are built into SSR time and other times when students are working independently.

One-on-one notes. The teacher confers with individual students, again measuring the depth of each student’s participation and thoughtfulness. These conferences are built into SSR time and other times when students are working independently.

Student thought logs are collected and assessed.

Student thought logs are collected and assessed.

In independent reading, students select books to read on their own. Of course, I do many things to help students “discover” high-interest books. The first, and by far the most important, thing I do is to make sure there are high-interest books in the classroom library, which helps me to match students with the right books. Here are other strategies I use to generate interest in books:

• I begin each class with a Reading Minute—a brief commercial on a book I think my students might read. I read something interesting to them for one minute.

• Students get up in front of the class and share books they are enjoying. After the first month of school, students sign up and conduct the Reading Minutes.

• I keep a large three-ring notebook in the classroom titled “Books We Recommend.” Inside the notebook, there are dividers labeled by genre (e.g., “sports,” “science fiction”). Each section has notebook paper in it, and when a student really likes a book, she creates an entry that lists the author, title, and a brief explanation on why she recommends the book. When a student doesn’t know what book he might read next, he can open the notebook, find his genre of interest, and look up book titles that other students have recommended.

• About once a quarter I conduct a book pass. When students walk in the door, there is a book placed on every desk. Each student reads that book for one minute, then passes it to the next student. In half an hour, each student is exposed to thirty good books. As they sample these books students write the titles of books that interest them in a “Books to Read” list. They can refer to their lists later in the year when they are at a loss on what to read next.

All my students like to read, but they don’t all know it yet. Getting the right book to the right kid at the right time is the key to developing independent readers.

The 20/80 Approach I am advocating in these pages is built on work that came before me—most notably by Richard Allington (2001) in What Really Matters for Struggling Readers and by Penny Kittle (2013) in Book Love. Working from their thinking, I now visualize what a year in the life of a reader might look like in my dream secondary school. Here is a possible week-by-week breakdown of that vision:

Or to think about it in a different form, see the curriculum map depicted in Figure 8.4.

Breaking the year down into a week-by-week schedule brings good news and bad news. On one hand, it is very helpful to see an overview of what a reading year looks like, but, on the other hand, I share this knowing my students will not fit perfectly into a cookie-cutter schedule. (What happens, for example, to the kid who wants to read a really long book—a book that cannot be finished in a three-week time frame?) In reality, a one-size-fits-all schedule does not fit all. Obviously, adjustments have to be made based on interactions with students. Given these limitations, however, I still think it is important to begin the school year with the “big picture” roadmap of my students’ reading journeys in mind.

Figure 8.4 A suggested reading curriculum map

For most secondary schools—and for many elementary schools as well—this proposed reading schedule is a very different paradigm for how to build readers. So different, in fact, that I suggest this school might be called Nirvana High School. To make this dream a reality, decision makers in our schools will have to think very differently. As I write this, for example, I am teaching at the Harlem Village Academies in New York, and I am fortunate enough to be in a school system that is willing and flexible enough to make sure it provides significant funding so that book clubs can occur. By the time you read this, however, I will be back teaching in a large urban district in California, and I anticipate that making the shift towards 20/80 reading will be much more problematic, if not initially impossible. Why? The obstacles are many:

• The philosophy behind the teaching of reading will need to change—for both teachers and administrators.

• Schools will have to rethink how money is allocated. It will be necessary to spend less on the acquisition of whole-class works; conversely, more money will have to be allocated for the purchasing of book club titles. At my school, for example, ELA only gets funding to buy books every five to seven years. If the money is not spent wisely, it is a long wait before the opportunity for reform returns.

• Money will need to be set aside so that teachers can build extensive classroom libraries.

• School librarians will need to rethink how they order books. Instead of buying one or two copies of a given title, multiple copies of specific titles will need to be ordered.

Given these obstacles, it is very likely that—due to the constraints of my school system—I will not be teaching this year in the 20/80 paradigm I am advocating in these pages. If, for example, I don’t have immediate funding to purchase books for my students’ book clubs, then book clubs will not immediately happen. Unfortunately, the way reading is taught in our schools is deeply entrenched and hard to change, but this doesn’t mean we should accept the status quo. What this does mean is that we should begin working diligently toward changing the paradigm, which, as you read this, is what I am doing.

Remember, the 20/80 Approach to the teaching of reading comes from answering the first question posed on my four-question rubric for evaluating teacher effectiveness: What percentage of your students can walk into a bookstore (or visit Goodreads.com) and know where to find books that interest them? As this chapter has illustrated, thinking about this question has deeply changed my approach to the teaching of reading.

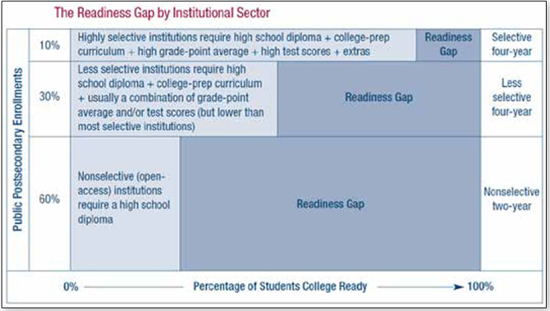

I now invite you to consider what other ways your practice would change if the other three questions posed on the proposed rubric of teacher effectiveness actually played a part in determining the level of your salary. In the left column of the following chart, you will find the three remaining questions; each of them, in turn, generate new questions worth thinking deeply about (found on the right).

REMAINING TEACHER-EFFECTIVENESS QUESTIONS |

NEW QUESTIONS WORTH THINKING DEEPLY ABOUT |

What percentage of your students write without being asked to do so by a teacher? |

• If your salary were contingent on developing independent writers, how would this change your approach to the teaching of writing? • What would your students’ writing journey look like over the course of the year? • What role would writing groups play in your classroom? • How would the use of models—from both professional writers as well as from you, their teacher—help your students to build their writing skills? • How would choice factor into your students’ writing lives? • How would your grading practices change? |

What percentage of your students can stand and speak effectively and confidently in front of a group of people? |

• If your salary were contingent on developing effective and confident speakers, how would this change your approach to teaching speaking skills? • Would you create more opportunities for students to practice their speaking skills? If so, when? How? Where? • What would your students’ public speaking journey look like over the course of the year? • How would the use of models—from both professional speakers as well as from you, their teacher—help your students build their speaking skills? • How would you assess a speaker’s “effectiveness” in a way that motivates your students to want to continue to develop their public speaking skills? |

What percentage of your students can actively listen to others—can carefully consider both what is said and what is not said? |

• If your salary were contingent on developing students who were active listeners, how would this change your curriculum? • How would you deepen the active listening skills in your students? • When and where would you give your students more opportunity to strengthen their listening skills? • How would you get students to carefully consider what is not being said? • How would you assess a listener’s “effectiveness” in a way that would encourage him or her to continue to sharpen his or her listening skills? |

With the four-question rubric for evaluating teacher effectiveness in mind, let me share a sample unit from my classroom.

Length: Three weeks

Note: Though this is technically a three-week unit, it will not necessarily fit exactly into a three-week period. The unit might be woven around other things that are going on in the class. If, for example, my students meet in book clubs on Mondays and in their writing groups on Thursdays, this unit will take more than three weeks to complete, even though the total teaching time remains fifteen days.

This unit is centered on an essential question: What makes a poem great?

If students are to gain an appreciation of poetry, they have to read a lot of poems. To ensure this, I begin by surrounding kids with numerous poetry books and I have them go on exploratory reading journeys. I want to make sure they are exposed to all kinds of poetry: narrative, haiku, free verse, elegies, ballads, epics, sonnets, spoken poetry, and so forth (for a list of high-interest poetry books, go to kellygallagher.org and click on “Kelly’s Lists” under the “Resources” tab).

In this unit, students will be creating poetry logs that chart their discoveries and their thinking. I distribute small composition books, and as they read through a number of poems, I require them to collect some that spark an interest. I ask them to copy the poems into their logs. Alongside their selections I ask students to share their thinking in written reflections.

While students are reading and reflecting on their poems throughout the week, I start every class period with a brief mini-lesson that helps them to read poetry more critically. For example, I might do a mini-lesson on recognizing the author’s use of metaphor, and how the use of metaphor deepens the reader’s understanding of the poem. Or we might study a poet’s decision making when it came to determining line breaks. Or we might study how punctuation is manipulated to create meaning. Mini-lessons are layered throughout the week to help my students become more discerning as they break out and read more poetry on their own.

By the end of the first week I want to see evidence that my students have gone on a deep poetry swim and that they have given rich thought to the poetry they have selected and studied.

After they’ve read poems for a week, I ask students to zero in on something worthy of deeper study. For example, one student might choose a genre of poetry worth delving deeply into (e.g., spoken poetry). Another student might latch on to a specific poet (e.g., Nikki Giovanni or Billy Collins) to study in greater depth. During this second week, students are asked to find something specific and to drill deeper.

As was the case in the first week, students continue collecting poems and writing reflections in their logs, but these collections and reflections now occur within the specific areas they’ve chosen to study. To prod my students to dig deeper, I may give them some of the following questions to consider: What makes this poet (or genre) worthy of study? Can you identify the “greatness” of this poet (or genre)? What makes this poet (or genre) distinct? Why has this poet (or poem) stood the test of time?

As students conduct this second week of deeper study, I continue to weave in mini-lessons to help deepen their understanding and appreciation.

The emphasis now shifts into having my students emulate the excellent poetry they have encountered. If, for example, a student has studied spoken poetry, she is asked to write spoken poems. If another student studied narrative poetry, he is asked to write narrative poems. Emulation becomes the work of this week.

Of course, as the teacher, my mini-lessons shift this week into a modeling mode. I, too, pick a poet (or genre) and do some emulation in front of my students, thinking out loud as I do so. I go, and then they go.

There are two culminating activities to the unit. First, we revisit the essential question (“What makes a poem great?”), and students consider the question through the lens of their three-week poetry study. And second, we end by placing the “author’s chair” in the front of the room, and each student sits in front of the class and shares an original poem.

Consider for a moment what I did in the poetry unit of study. I designed lessons that were student centered and in which kids did the exploring and the heavy lifting. I surrounded them with good books and mentor texts. I created an environment where students both read and wrote a lot of poems. I wove in a number of mini-lessons that deepened their understanding and appreciation of poetry. I built in lots of choice for the students, for I believe all students like to learn when given an opportunity to explore their own interests. And I made sure there was an oral component as well by creating an environment where lots of poetry was spoken and where lots of poetry was heard. Woven together, this poetry unit felt more like a celebration of poetry—a unit where kids left my class looking forward to reading poetry again later in life.

Now take a moment and consider what I did not do in this unit of study. I did not sit down and sweat over thirty-six Common Core anchor standards. I did not plan with any distant state test items in mind. I did not create a checklist to see which standards I covered. I did not distribute a single worksheet focused on strengthening my students’ skills. I did not administer multiple-choice quizzes to prepare them for the exams in the spring (in fact, I didn’t give them any quizzes). I did not, as Billy Collins (1988) warns, have them tie poems to chairs and torture confessions out of them. Most importantly, I did not drill the love of poetry out of them.

Did this poetry unit address many of the current Common Core ELA standards? Certainly. But it is also important to note that this unit moved beyond the current standards by asking my kids to do things that are not measured by CCSS-aligned exams. This unit was not designed with the CCSS (or other newly adopted standards) in mind. Instead, I designed the unit with one question in mind: What is in the best interest of my students? The answer to that question sometimes aligns with the latest standards and testing movements; often, however, it does not. So let me finish this book by reminding you that rich language arts instruction is steeped in what works—regardless of the current political winds—and what works is often found in the answer to the question I hope all of us will continue to ask: “What is in the best interest of my students?”