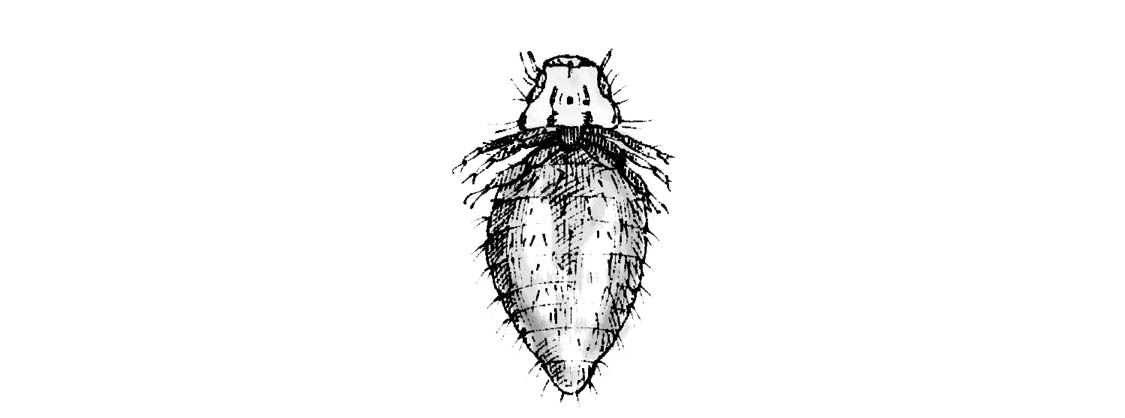

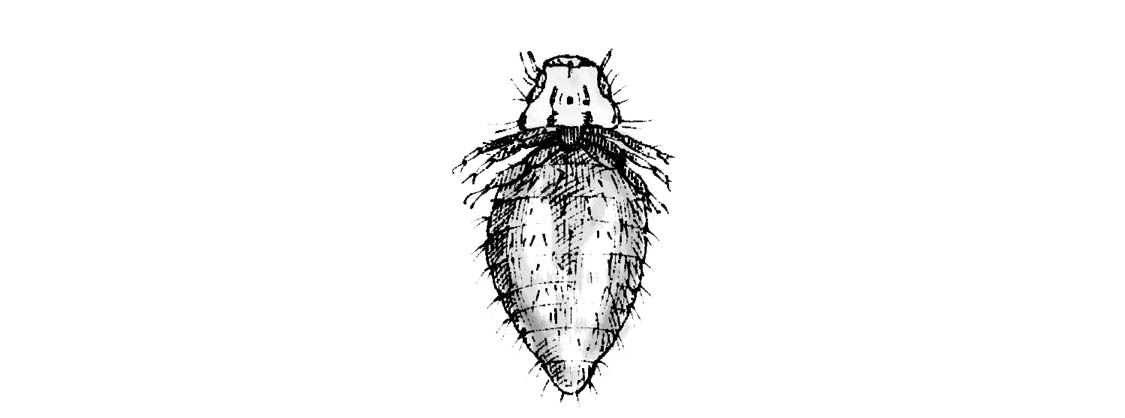

Louse. This is typically what you are looking for.

One of the most important parts of the showing process is the general health of the bird. A weak, sickly-looking bird will not place well even if it is perfectly marked, colored, and of proper size. Judges will carefully evaluate a bird’s overall health, from comb color and texture to the condition of the feathers and legs. Birds that have respiratory problems also tend to have a particularly unpleasant smell that a trained judge can notice rather quickly.

Parasite prevention is crucial during the growing-up period. Waterfowl will nearly always take care of themselves with their constant bathing, but it is still important to check for lice and mites. In all my years, I have seen lice and mites on waterfowl only once, and those birds had been deprived of the ability to bathe daily and keep themselves clean.

Turkeys and guineas will also, in most circumstances, keep themselves clean and bug-free. Occasionally lice will be an issue, but give the birds a good place to dust-bathe and they will, in most cases, take care of the issue.

Chickens have the biggest issue, as lice and mites will find them with little or no difficulty. Periodically check the vent areas and under each wing for signs of lice and mites. The creatures will leave their telltale traces: rough or damaged tissue, missing feathers, and/or egg cases on the feathers.

It is easiest to check for lice by picking up the bird, holding it in one hand, and then carefully parting the feathers around the vent area with the other hand. Look quickly, as the lice will scurry away — they will be a pale, creamy orange color, and they move fast. There are other species of lice that are larger, slower, and various shades of gray. Most lice will leave egg cases that look like gray matted areas in the feathers.

Mites can be of several different species that will in some cases resemble fine grains of pepper. They tend to appear in large masses and will crawl very slowly. The damage they do can be extensive, both to the individual bird and to all members of the flock, and they are harder to kill than the typical louse.

Sticktight fleas, which typically gather around the eye, can be a problem in some of the warmer areas of the country. I have no personal experience with these creatures, but the friends I know who have to deal with them indicate they are very hard to manage.

The best way to control mites is to find a spray that works, and gently, and on a regular basis, do a maintenance check and spray as needed. There are a number of good sprays on the market, and many more are constantly becoming available. Use care and make sure you read the directions as to how toxic each product is. Most important, do not overuse. It is also a good idea to alternate between two types to keep the parasites from developing resistance.

As a natural approach to control lice and mites, and to a lesser degree sticktight fleas, fill a large metal tub with woodstove ashes or diatomaceous earth, or a combination of the two. Place the bird in the tub so it can sit in the material and fluff it up into its feathers. This will be somewhat effective for a large infestation, but it is far more effective when done before the mites and lice become thick and plentiful on the bird.

An increasing variety of sprays is available, ranging from all-natural ones to those that contain harsh chemicals. You have to decide which approach you are most comfortable with and which one works to eradicate the pests from your flock.

Louse. This is typically what you are looking for.

If you are able to carry over birds and show year-old or older birds in hen and rooster classes, another parasite you may encounter is the scaly leg mite. These obnoxious creatures spend their lives making both chicken and owner miserable — not that they get into the owner’s skin, but the frustration from dealing with them brings on a great deal of stress. Though tiny, they can cause great damage to the bird they choose to live on, burrowing into its leg and creating large, crusty areas. Eventually they can kill the bird.

For years, the only commercial treatments available for the mites were for caged birds, and the prices were not user-friendly for poultry raisers. At last there are several commercial remedies for sale at lower prices. The old standby homemade recipe still works great, however: mix 50 percent raw linseed oil or motor oil and 50 percent kerosene, then, wearing gloves, use a paintbrush to paint it on the chicken’s legs. Raw linseed has become hard to obtain, so I have switched to using motor oil in place of raw linseed oil, and that is just as effective.

Scaly leg mites. These are usually a problem only in birds older than 1 year.

Internal pests are rarely a problem for most exhibitors, but this can be an issue for free-range fowl and those raised on soil where previous flocks were raised. Things to watch for include poor feather development and thin birds without much energy.

If this becomes a problem, you will need to use a deworming medicine. These can be harsh, and your birds will need a nutritional boost following such a treatment. It is always best to add a probiotic or vitamin supplement once you have wormed poultry.

There are a few things to watch out for with each species of poultry, but waterfowl require the most attention, as you need to watch for proper wing development. Too rich a feed (that is, too high a protein level) will cause major feather and wing development issues in young ducks and especially young geese. Watch that the feathers are forming properly and the bone structure beneath is sturdy enough to carry the feathers; if they get so large they weigh the bird’s wings down, the bird can get airplane wing or angel wing. This condition will end the bird’s chance to become a show champion.

Other waterfowl issues to watch for involve the feet. Waterfowl raised on concrete or gravel will have rough feet, which in some cases develop raw, red sore spots that will also decrease show potential. These birds do best when they are given a good balanced diet, can walk on grass or soft soil, and are allowed to be in the water frequently.

Foot issues in waterfowl. These are the feet of a bird that needs softer landscaping and a more balanced diet to keep its feet in better condition — for its health and comfort, and also for showing.

Turkeys and guineas are a bit more of a challenge for the show person. Heritage turkeys grow slowly, and you need a good four months prior to the show for them to look their best. (Three months is okay but not ideal.) Commercial strains of turkeys for meat classes will require less time but have additional issues. They require a high-protein ration of feed and frequent cleaning of their living area, more so than do the heritage birds.

Commercial turkey strains tend to sit down a lot and do not move around and roost the way the heritage types do. Heritage turkeys will start flying around at a young age and like to roost when they are 3 to 4 weeks old. Roosting keeps birds cleaner and more show-worthy. Commercial strains of turkeys rarely (if ever) roost and therefore spend most of their time with their breast area next to the floor.

Unlike heritage turkeys, which have solid, dry stools, commercial strains tend to have a liquid and messy stool, so more ends up on the bird. This means if you are showing a commercial meat pen of turkeys, you must have excellent maintenance skills, frequently changing the bedding as they age and the show draws closer. Improper maintenance will result in poor feather development on the chest and a dirty overall appearance.

When showing commercial meat turkeys and modern commercial broilers, the same advice applies to both: keep raising the feeder a bit as they age so that they constantly have to move around and don’t get in the habit of sitting while they eat. This not only helps keep them slightly cleaner, but it also encourages better muscle development and proper feather growth on the chest.

Guineas are a breeze when it comes to preparation. Give them a dry, clean place and spend some time with them to calm them down. These birds also usually remain pest-free.