4

Understanding the role of heritage tourist experience

A netnographic research in Italy

Introduction

This work investigates the concept of cultural heritage through the visitor’s perception of a tourist experience and in relation to this, how small entrepreneurs of the tourism industry can leverage such a value. We studied heritage in its intangible elements, examining the reports of an online community by means of qualitative analysis.

Firstly, after introducing the concept of the heritage tourist experience, we will focus on its intangible components. Very often the cultural and historical heritage of a place is applied only to material elements such as monuments, museums and landscapes, thus ignoring the importance of its intangible components, which are always present and as much relevant (UNESCO, 1972; Greffe, 2004; De Varine, 2005; Faro Convention, 2005; Vecco, 2010). In particular, the authors pinpoint the intangible elements of the cultural heritage of a specific place that visitors perceive as most significant, analysing the emotional relationship established between them and the tourist.

Since the eighties, holidays are no longer considered just as a mere moment of recreation and rest, but as an opportunity to go through new and authentic experiences connected to the discovery of innovative culinary products, sites linked to important historical events, or customs and traditions of still unknown territories (Sims, 2009). For the heritage tourist, both tangible and intangible local resources are true attractions, interpretable as real motivational factors (Rispoli, 2001). Given the experiential dimension of tourism in general, it becomes crucial for local marketing managers to analyse emotions, feelings and motivations connected to the experiences undergone during the holiday. For these reasons, the research was carried out according to qualitative methods, which were considered more appropriate for the investigation of this phenomenon (Casarin, 2005; Prayag and Ryan, 2011).

In this research the netnographic method developed by Kozinets (2002, 2006) was employed in order to carry out marketing qualitative researches. This method, starting from a solid ethnographic methodological basis, was then readjusted so that the information found in web forums, blogs and online communities could be used for the study of the sentimental relationship built between the consumer and specific products or services. In this work, the authors apply this method to the analysis of the tourist experience, particularly to analyse the concept of heritage through reports freely shared online by the beneficiaries of this experience. To this purpose, travel journals concerning four Italian cities (Florence, Naples, Rome and Venice) were compared to each other. The research has shown to which extent heritage intangible elements are present in the analysed reports, assessing the major role they cover in the motivational process and in the satisfaction of the tourist. In particular, it was shown that some elements have a greater intensity than others, being capable of determining the satisfaction of the entire tourist experience as well as covering a key role in the desire of living that experience again.

Heritage and tourism as a subject of research

According to the definition given in the Cambridge Dictionary, the term heritage is related to “those characteristics belonging to a particular society, such as traditions, languages, or buildings, coming from the past but still determinant nowadays” (Merchant and Rose, 2013:2620). According to Prentice (1993), heritage is classified in respect of the type of attraction it offers, thus conceptualizing its possible subdivision into: (1) natural heritage (Butler and Boyd, 2000); (2) cultural heritage, both immaterial (Butler and Hinch, 1996) and material (Ashworth and Tunbridge, 1999); (3) industrial heritage, regarding the actors of a place that have contributed to its economic development in the past (Graham, 2002); (4) aspects of a place that have a relevant meaning for an individual or for a group of individuals (Lennon and Foley, 1999).

With specific reference to the touristic industry, since the eighties a new type of tourism called heritage tourism (Prentice, 1993) has started to develop. Many authors have addressed several aspects of this phenomenon, from problems concerning the management of heritage sites (Garrod and Fyall, 2000), related marketing activities (Bennet, 1997), destination selection processes (Swarbrooke, 1994), the characteristics of this new type of “heritage tourist” (Richards, 1996), and the dimension of heritage possessed by a particular location (Poria, Butler and Airey, 2003).

For the purpose of this study, it is important to delineate different types of heritage tourism (Gilli, 2009). In the literature two main approaches to define this phenomenon emerged; the first deals with the “objective” dimension of the visit, e.g. a specific destination, monument, historical site etc., considering it as a discriminating factor for defining a touristic experience. Thus, attention is focused on the characteristics that such a touristic “target” should possess (Poria, Butler and Airey, 2003). Contrarily, the second approach concerns a “psychological” dimension, based on motivations and attitudes that drive an individual to visit certain places (Poria, Butler and Airey, 2003). Although motivations are fundamental elements for any form of tourism, in the case of a heritage tourist they are of even greater importance Urry (1995:119); the term “tourist’s gaze” indicates a set of subjective dispositions shown by a person toward a given destination. A relationship between the tourist and the visited place is therefore built by increasing elements such as nostalgia, sense of belonging, identification and search of an identity (Wang, 1999).

In this work we use a psycho-anthropological approach that considers the heritage tourist’s experience with respect to the journey; this is not only characterized by visual experiences concerning historical buildings, areas and landscape (Laws, 1998), but also rather aiming at discovering peculiar lifestyles, values, traditions and traditional events connected to a place’s cultural heritage (Richards, 1996).

According to Gilli (2009) the heritage tourist experience is based on three essential elements: (1) the subject, (2) the interpretation process and (3) the process of active acceptance. The first element indicates the attraction of heritage tourism for a tangible or intangible object that entails the memory of a past, though not referring to a recent past in the temporal sense, but rather in the cognitive sense, triggering a relationship between the object and the visitor (Urry, 1995). The second element refers to the relationship between the object and the visitor, i.e. the process by which the object of the visit conveys its meanings, creating a relationship between the visitor and the visited object (Fyall, 2008). The process of interpretation must therefore be examined in a multidimensional perspective, not only restricted to the transmission of information, but also considered in an educational perspective, emphasizing the relationship between the object and the present world (Tilden, 1977). An interpretation of the touristic experience cannot be regarded as a purely intellectual operation, given its sentimental and emotional implications (Gilli, 2009). In order to experience a heritage, it is not enough that the visitor is “physically” on site, but a participative attitude in the building of a relationship with the object is required, i.e. the tourist must seek an emotional involvement rather than only a staring occasion. Finally, the third element is the acceptance connected to the implicit concept of inheritance hinted at by the word heritage, i.e., a sense of receiving. This process can be studied at three levels (Gellner, 1983): (1) a cognitive level, in which the individual recognizes her/his own role as heir in regard to a particular symbolic object; (2) an affective level, which includes the feeling and desire for identification; (3) a conative level, which directs the individual’s behaviours and consequently this is the actual level of her/his participation.

Thus, the essence of the experience for heritage visitors/tourists is the full immersion in a place/site, with emotional and cognitive features which promote the role of the subject as participant and active user (Brakus, Schmitt and Zarantonello, 2009).

For these reasons, it appears that the heritage tourist differs from the “traditional” one not only for her/his desire to seek and revive the heritage during the holiday, but especially for her/his need to live a multisensory experience, involving visual sensations, sounds, local customs and traditions (Hall and Zeppel, 1990).

Currently, the tourism industry observed a growing demand of typical environments capable of transmitting the history of the place, thus enhancing its traditions, habits, customs and culture. More and more, places where events are hosted, such as wine and food festivals or historical re-enactments, are turned into touristic destinations. This is probably due to an easiness of real-life, social and communicative relationships that strengthen the bonds and the sense of community (Hughes, 1992; Warde and Martens, 2000).

A narrative approach for the heritage tourist experience

The heritage context considers cognitive and affective components as essential variables (Rust and Zahorik, 1993; Boss, 1999; Giese and Cote, 2000; Szymanski and Henard, 2001; Chi and Qu, 2008; Wong and Dioko, 2013; Bansal and Taylor, 2015). The experience of the heritage tourist can hardly be assessed by exclusively quantitative instruments, making it necessary to resort to qualitative techniques in primary or supplementary ways, such as the mixed method approach (Greene, Caracelli and Graham, 1989).

Recalling the perspective of the Consumer Culture Theory (Arnould and Thompson, 2005) and tribalism (Maffesoli, 2004), the focus is shifting more and more on the micro-social context by integrating approaches deriving from anthropology and ethnology (Cova, 2003). These new methods differ from methodologies solely based on questionnaires, classical interviews or focus groups. Following this perspective, an incisive ethnography of consumption should be based on participatory observation as well as on the respect of the interpretative models of the local and personal culture of the consumer (Sherry, 1995). Therefore, the introspective narration produced by the consumer in the form of comments, stories, interviews, journals and videos becomes fundamental. This new narrator role played by the consumer is stimulated by the increasing presence of “self-reflective” individuals, whose insight allows them to tell their stories and explain their actions, thoughts and motivations by the means of words (Cova, 2008). The post-modern ethnography model is therefore based on the use of introspective narration also known as “big stories”. These narratives are intended as life narrations and autobiographical accounts to describe the subjective and inner or collective dimension of the experience of consumption of goods and services (Georgakopolou, 2006). Thus such stories, verbal or not, regarding a lived experience, are keys to get access to the inner sphere of an individual.

The choice of an ethnographic method is also justified for two other orders of reason: an experience, as already expressed, is mainly related to feelings and emotions of a great intensity, fact that distinguishes the tourist experience from a normal daily one; the second concern relates to operations of reworking, rethinking, and framing of what happened into a narration (Carù and Cova, 2008). Accordingly, experiences communicated, explained and shared, through the creation of a narrative, move from one’s own inner sphere to the outside world. A further important aspect is the management of temporality. The story involves a linguistic representation in which events, objects, actors and moods are placed in relation along a time path that requires the distinction between “before” and “after” (Poggi, 2004). In addition to this, a narration involves actions such as the identification and the selection of aspects that turn out to be more meaningful and relevant to the experience itself. Through the identification and selection of experienced events, the narrator manages to convey a sense of reality and simultaneously s/he outlines a logical/emotional order. Through this process, a perceptual and emotional sense can be assigned to experience, because narrated events need and refer to a logical structure of reality that is congruent to the interpretation of the teller (Longo, 2006). Thus, the narration also becomes relevant from a sociological point of view since it can “relate” the individual to the social structure (Jedlowski, 2000), connecting the inner sphere of the teller to the story/experience.

In tourist experiences, narration is at the central stage (McCabe and Foster, 2006). Touristic narration develops a sense of belonging (Bird, 2002), emphasizing its contents. Through it, the individual is able to transmit his own interpretation of what s/he saw and experienced, but at the same time s/he selects the most salient elements of the experiences, thus creating a symbolic construct that forms the heritage tourist experience (McCabe and Stokoe, 2004; McCabe and Foster, 2006; Tussyadiah and Fesenmaier, 2007; Young, 1999).

Several scholars (e.g. Crompton, 1979; Dann, 1981; Baloglu and Uysal, 1996; Poria, Butler and Airey, 2003; Yoon and Uysal, 2005) stress the awareness of the traveller as the trigger of the experiential process of heritage tourism, reflecting the sensitivity of the subject and her/his motivation to visit a particular place rather than others and this also determines the level of participation and enjoyment of the visiting experience (Solomon, Bamossy and Askegaard, 1999; Yoon and Uysal, 2005). Moreover, awareness affects the capacity of perception of the tourist with regards to the heritage of the place. This is because such awareness increases the ability to frame the real level of heritage of a site, a factor that in turn implies a behavioural intention to visit and revisit the site, as well as the interest in visiting similar sites (Clements and Josiam, 1995; Swarbrooke, 1996; Josiam, Smeaton and Clements, 1999; Poria, Butler and Airey, 2003).

In this research, we decided to study the heritage tourist experience in four different Italian cities and what intangible components of it emerge and which are most attractive for visitors. In particular, the aim is to uncover elements of the intangible cultural heritage, which are best perceived and remembered during the experience. To this end we will analyse the narrations that visitors share freely and publicly on the web. Since this issue has already been analysed by several studies, mainly through surveys (Yang and Cen, 2011; Chung and Petrick, 2013), it was decided to use the netnographic method. This choice is appropriate for examining this kind of experience for which conventional evaluation methods such as questionnaires turn out to be inadequate to understand the relationship established between the visitor and the visited object (Casarin, 2005; Kelly & Thrift, 2009; Chandralal, Rindfleish and Valenzuela, 2015). To operate a fully ethnographic research, the language used by the tourist should be the unit of analysis (Gobo, 2001), carrying out semi-structured interviews or resorting to the narrative directly produced by individuals (Longo, 2006).

We opted to examine stories written by travellers, containing tourists’ recounts of the most intense moments and sensations experienced during the holiday. Nowadays, thanks to the web and in particular to social media, accessing narrations of individuals is much easier and cheaper than before. Online communities represent new places where research can be carried out (Kozinets, 2002) and the netnography is able to process an enormous set of information contained in the narrations produced and published online by travellers to uncover relationships between the visited object and the elements of the personal experience of the tourist (Tilden, 1977).

Method

The first phase of a netnografic approach consists in data extraction. We performed a web search on Italian blogs, forums and websites, where journeys are the main theme. Further we privileged those presenting complex narrative structures, thus with richer contents to be analysed. The final choice was directed to the blog “Diari di viaggio” (Travelogues) on the website http://turistipercaso.it, as it presented the most comprehensive collection of narrations on travel experience in Italian cities. This blog is characterized by extensive narrations, written with an intimate and introspective style, useful to reveal the feelings and emotions of travellers. Unlike the forum on the same website, the blog section is more flexible with a greater freedom of expression, which encourages users to elaborate on the experience and events of the holidays with a more reflective and personal perspective. Moreover, this virtual space can be interpreted as a virtual community where each user is a traveller and lived such an experience, thereby increasing the accuracy and relevance of the reported information (Ranfagni, Guercini and Crawford Camiciottoli, 2014). Indeed, also from a quantitative perspective, this website seems appropriate given its high rank in search engines, high numbers of visits and the presence of more than 27,000 travel diaries regarding cities all around the world.

After choosing the website, we also targeted four Italian cities, with the aim of identifying the factors of cultural heritage that could better explain differences and similarities between examined cities. The choice fell on Florence, Naples, Rome and Venice. This decision was justified by the fact that these four cities are characterized by a significant artistic, historical and material heritage. Furthermore, these are the cities with the highest number of stories, allowing to perform a research with a significant data sample.

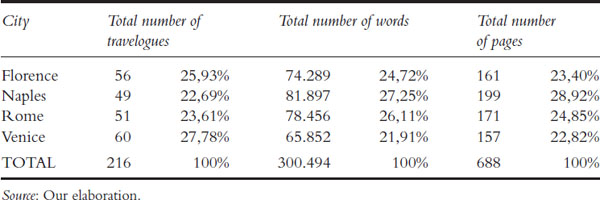

We decided to employ a total amount of 216 travelogues distributed among the four cities, which has been extracted and transcribed. Although the website managers perform a primary quality control on the published travelogues, eliminating those not relevant nor focusing on travel experiences, we paid particular attention to the quality of the travelogues, excluding those that were not suitable for the purposes of the research or those not rich enough. The following table (Table 4.1) illustrates the characteristics of the research sample; the number of pages has been calculated with line spacing 1.5 and font size 12.

The second phase, data coding, was initially carried out manually in order to perform a basic exploration of the data, and then move onto Nvivo software for an accurate coding analysis (Saldaña, 2012). This software is specifically designed to assist the researcher in qualitative analyses, facilitating the management of large masses of data both for reading and querying. Practically, data analysis touched two aspects: (1) the identification of heritage intangible factors that occur more frequently in the dataset, using a checklist; and (2) the identification of emotional references in respect of the visited place that emerged spontaneously from the stories. For the coding analysis, it is important to stress the results obtained. First a set of elements generally called categories represent conceptual issues/objects to classify a text, while the quotes (or codes) – portions of text that are expressions of the categories – are used to form homogeneous groups of recursive concepts in all the travelogues (Neuendorf, 2002).

Subsequently, in the third phase, two of the authors who were not involved in the process of classification and codification, independently verified the goodness of the classifications conducted. This step was able to verify the internal and external reliability of the coding process. A random sample of quotations and categories were selected and presented to independent authors. The authors independently linked them together to simulate the early stages of the work, but without carrying out a further codification. This step was necessary to ensure greater accuracy and an impartial data analysis process as suggested by the most recent literature on this subject (Kozinets, 2015).

Finally, in the fourth phase, always referring to the literature on the ethnographic method (Altheide, 1987; Worthington and Whittaker, 2006), textual analysis (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008) and the netnographic method (Kozinets, 2015), the authors have rounded up to assess if other macro-categories might emerge from the grounded analysis, performing the task of verifying the saturation of concepts.

Findings

The objective dimension of the touristic experience

The initial step was to define heritage-intangible categories so related quotations could be identified in the travelogues. For the creation of these categories we used a descending approach (or closed checklist approach), which implies that categories are defined in advance, regardless of the structure of the text. In this case we employed the widely accepted classification proposed by Kelly and Thrift (2009), who classifies the cultural heritage in built, natural and living. Since our goal is to identify intangible heritage factors, we discarded the built and natural variables and focused our attention on the variables of the macro-category “living heritage” that refers to the heritage that is socially embedded in the place visited. Once categories were defined, the real analysis and encoding began. During this process stories were manually analysed line by line. After identifying the portions of text referring to the elements of the living heritage, those were then linked to categories. In the following paragraph we describe categories together with some examples of associated quotations (see Table 4.4).

The “craftmanship” category refers to all the typical economic activities of artisan nature that are history-imbued. The “songs and typical local music” category identifies particular musical traditions of a place or of a community that embody its history and customs. The “local community” category refers to all aspects of the daily life that distinguishes a place. “Festivals, typical local events, religious events” refer to recurring events such as festivals and local celebrations that become typical when they are fuelled by the local community. “Typical local language” pertains to languages and dialects of a given local community. The “typical markets and shops” category refers instead to those local commercial activities not directly related to artisanal production. Finally, the last category, “local wine and food traditions” includes the entirety of gourmet products and food-related events that characterize the culinary tradition of a given area. Table 4.2 indicates the different categories and examples of quotations linked to them.

Table 4.3 summarizes quantitative information identified during the encoding of the travelogues about quotations from the previously mentioned categories. The first value, in brackets, refers to the number of travelogues in which quotations related to a specific category have been identified. The second number instead indicates the number of identified quotations. Finally, the percentage shows the “relative weight” of each category (number of quotations related to the specific categories on the overall number of identified quotations). Analysing further this information, the category of food and wine traditions has the highest number of quotations in all three cities.

The stories concerning the visits to the city of Venice have the highest values in the categories of craftsmanship and festivals and typical local events. This high value of the craftsmanship category in Venice may be justified by a thriving industry related to craftsmanship productions, e.g. the laces of Burano or the hand-blown glass of Murano. As for the festival and local events category, Venice can boast a worldwide-known event: the Carnival of Venice. Florence has the highest number of quotations concerning typical markets and shops. Rome displays high values with regards to the interaction with the local community; it also has high levels of quotations about religious events, due to the presence of the Vatican State. Naples offers a larger number of quotations in the categories relating to language, local community and food and wine traditions. Finally, the values concerning the music and songs category are generally very low; slightly higher values are recorded in Naples.

| Category | Quotations |

|---|---|

Craftsmanship |

“We really dunked into an unknown Florence by appreciating the various scents of soaps of an old pharmacy, tea flavours, masks and handcrafted objects, smells and tastes. We really had the feeling of living in a different reality!” [Florence] “Obviously you cannot refuse to visit any of the many shops, feel the smells, hear the sounds, observe unique items. All your senses are involved in this magic”. [Naples] “The demonstration really leaves everyone breathless, glass craftsmen manage to create their work handling for some instants heated glass balls, then leaving them in the oven and transforming them into objects that we all know well! It’s wonderful, a really unique experience!” [Venice] |

Songs and typical local music |

“In Venice, in the calmness of its alleys, the silent furrow of Gondolas interrupted from time to time by the bells of some church, by the orchestras of St. Marco Square and by the street artists, all of this bring us into a distant mysterious world, almost magic and dreamlike”. |

Local community |

“Yet it has its own charm and it must be visited at least once in a lifetime. For the pleasure of getting lost in its narrow alleys and then find a person willing to help you to find your way”. [Naples] “It has much more to offer, it has its people, it has the majesty and the wonder that you can feel while walking and speaking with strangers as if they were your friends”. [Naples] “It was exactly how we expected it to be: congested and crowded alleys full of noisy people, elegant buildings, chaotic traffic, horns used without economy”. [Rome] |

Festival, typical local events, religious events |

“From the first steps we immediately notice that the atmosphere is different, masked people coming out from everywhere, those who choose their own animal (lions, tigers, crocodiles, wolves), those who choose the mask of some Venetian Lord of the 18th century, and those who decide to play the barbarians. In Venice, also the rowers are masked! There really is the desire to have fun and forget about the problems of this crisis for just one day”. [Venice] “Around the Basilica you can find banquets of sweets, toys for children and candles, that are lighted all day long by believers in the churches, the Candelèta de la Madona Benedeta (edit: the candle-light event for the Holy Virgin). Despite the strangers, this is a truly Venetian festival and deserves to be experienced at least once!” [Venice] “An emotional pause even for a non-Catholic like me: this is the place where you can regularly see the warmth and the brotherhood of the people of this city, that reunite with great charm during the ceremony of the Holy Blood liquefaction”. [Naples] “So in Venice you can really say that there is a continuous feast!!! No coincidence that the artists from all around the world come to this city for inspiration”. [Venice] |

Typical local language |

“to make it a pleasant evening there were also the waiters and Bobo (edit: the owner) himself with their jokes in Tuscan dialect, who took the mick out of us but always within the limits of amusement, especially if you have sense of humour”. [Florence] “It’s very strange to see Venice at this hour of the day, you can finally hear people speaking in dialect”. [Venice] “The Neapolitan atmosphere surrounds us, with sounds, colours, flavours” [Naples] |

Typical markets and shops |

“the streets of the city centre are very typical, with their fruit shops (cedars were incredible!) and obviously limoncello (edit: traditional liquor obtained from lemons) of all types, it seems to have stepped back in time!” [Naples] “In the centre, in addition to stalls and local markets, there are shops of all kinds and for all needs, like the boutiques of major Italian brands such as Patrizia Pepe, Armani, Prada, Coveri or Dolce&Gabbana. You can find shoes and leather goods boutiques like Ferragamo but also antiques, books, food and wine. So, nothing’s missing”. [Florence] |

Local wine and food traditions |

“Florence has an incredible variety of taverns and typical restaurants of all kinds and for all budgets”. [Florence] “There are so many Bacari (edit: traditional taverns) where Venetians stop especially at lunch and where you can taste the cicchetti, that is to say having small portions of polenta, fish, fried vegetables, creamed cod, sardines in sauce and many other delicacies, together with a glass of Venetian wine”. [Venice] “One thing that we immediately want to point out about Naples is its sweets: the pastiera, the sfogliatella, but especially the Babà that we discover with amazement to be really tasty”. [Naples] |

Source: Our elaboration.

The psychological dimension of the touristic experience

Whereas in the previous data analysis we used a closed checklist to define categories for cataloguing purposes, such a decision seemed not proper for a more complex analysis focused on psychological and attitude elements.

In this third phase of research, we did not follow a “descending” approach again for the definition of macro-categories concerning the evaluation of the experience lived by the visitor; instead we employed an “ascending” approach (without checklist) of grounded type (Charmaz, 2014). In line with this, categories are not defined a priori, but they are identified and defined during the process of encoding of the text, according to the information that emerged during its analysis. The authors decided on this approach as the literature on ethnographic methodology (Altheide, 1987; Worthington and Whittaker, 2006; Timmermans and Tavory, 2007; Charmaz, 2014) and netnographic methodology (Kozinets, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2015) recommends letting data emerge naturally from the textual context without using checklists that could influence the discovery of elements that are already naturally embedded in context (Charmaz and Mitchell, 2001).

Furthermore, such an exploratory approach is proper for several aspects: (1) the ethnographic method, specifically netnographic in this research, is not just a tool of analysis of “aseptic” frequencies or correlations; rather it is an interpretative approach to a context. After having validated the variables already present in the literature, we decided to disregard the use of closed checklists in accordance with the previously mentioned literature; (2) the fact that the literature on our specific topic is not sufficiently vast nor specific enough to allow a precise use as a set of pre-established variables; our interpretative results confirmed the goodness of this choice; and (3) psychological aspects that influence the selection of a destination are a personal and inner expression of the traveller, possible with an infinite number of patterns (Ulusoy, 2015); therefore we considered to be a limitation the use of closed checklists for this inquiry, as a matter of fact preventing emergent patterns to be fully analysed (Angrosino, 2007). Table 4.4 highlights the main categories emerged from the process, along with examples of associated quotations.

| Macro-categories | Quotations |

|---|---|

References to the uniqueness of the visited city |

“It is something more than discovering the usual Italian art city. Florence charms and fascinates with the splendour of its squares, with the magnificence of its museums, with the romance of the walks along the Arno river with its beautiful Ponte Vecchio”. “It conveys a pleasant sensation, and after waiting many years to visit it, I understand now the saying ‘see Naples and die’. It is true: to see and to appreciate its authenticity makes you just think that you can’t find a place like that elsewhere in the world”. “Venice is beautiful because it is different from all other cities. To make a small and almost insignificant example: when you ask for directions, people don’t tell you the corner, but the bridge to be taken. It really is a special reality that catches you and never lets you go”. |

Desire, intention to return |

“We vowed to return, because Florence needs to be enjoyed bit by bit”. “and so we promise ourselves that next time our tour will start again from here …” “Goodbye Venice, see you soon magic city!” “Hopefully we will be able to come back and enjoy again the same pleasant atmospheres we experienced”. |

Sensation of reliving the past |

“A dip into the Neapolitan culture and at the same time a journey back in time, among family-run pastry shops, unforgettable sfogliatelle and babà [edit: traditional fresh bakery products], and fish shops where you can see eels and capitoni [edit: large eels] splashing around small tanks”. |

Source: Our elaboration.

The three identified categories do not relate so much to specific physical objects or material entities, but rather to feelings, impressions and psychological elements that are naturally associated with an experience. Obviously, the identified components include both positive and negative judgments about the recounted experience and this proves the goodness of the approach, allowing for a greater level of “authenticity” in reconstructing the experiences (Hosany, 2012). Looking at the quotation the emotional connection of the teller with the recounted experience is evident, and considering that these travelogues have been written ex post they should report only feelings and events of a greater intensity.

Data inserted in Table 4.6 are those that emerged from the encoding process concerning the quotes in which the visitor-narrator expresses her/his sentimental and affective considerations in regards to the place. The table reports the same information of the previous data analysis (Table 4.3), i.e. the number of travelogues related to a specific category, the number of identified quotations, and the “relative weight” of each category. For a better explanation of the percentages, a graphic representation (Figure 4.1) has been also presented, and Table 4.5 shows the cumulative number of travelogues and quotations divided into macro-categories (regardless of the city to which they referred).

According to their values, Naples and Rome are perceived as the cities that most involve the visitor from a sentimental point of view. This grounded analysis has highlighted that the most recurring immaterial heritage element in the travelogues is the desire and the intention to return to visit the city. The detection of this element shows that in heritage tourism a positive tourist experience seems to be linked to the desire and the intention to return to the place. Other researches in the tourism field (Beerli and Martin, 2004; Qu, Kim and Im, 2011; Giraldi and Cesareo, 2014) get to the same conclusion by demonstrating that positive experience is often associated with the perception of a positive image of the place; however, these other studies never identified the immaterial components connected to the heritage, a task that was carried out in the sixth phase of this work. It is also interesting to note that a negative sensation associated with this type of tourism concerns the perception that the city is no longer the same.

Figure 4.1 Histogram of visitors’ quotations with regards to the visited city

Source: Our elaboration.

| Macro-categories | Number of travelogues | Number of identified quotations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

References to the uniqueness of the visited city |

30 |

22,56% |

44 |

27,50% |

Desire, intention to return |

78 |

58,65% |

89 |

55,63% |

Sensation of reliving the past |

20 |

15,04% |

22 |

13,75% |

TOTAL |

133 |

100% |

160 |

100,00% |

Source: Our elaboration.

Ultimately, a further important fact emerging from the analysis of the travelogues that can easily be noticed from Table 4.6 concerns the desire to return. In fact, 58.65% of travelogues show at least one quote about the desire to return to the visited city in order to deepen or relive the experience. This element has persuaded the researchers to analyse in the sixth part of the work the motivations that drove individuals to return to a place already visited.

Implication for the “motivation to return”

From the last analysis, the one interesting result is the intention and the desire of the writer to visit the city again in the future.

Therefore, we focused on seeking causal relations between the values related to intangible heritage elements regarding the relationship between the visitor and the visited city. The occurrence of such an intense desire to return to visit a place prompted the authors to investigate what were the factors related to the desire to return for the sake of reviving or deepening one’s experience.

The analysis of the values of the quotations of these travelogues showed that some categories had a greater intensity. It was therefore assumed that these categories had more weight within the visitor’s motivational process. Table 4.7 summarises the categories used for the detection of the tourist’s desire and motivation to return.

As it can be noticed, those who want to return to visit the city are motived by elements such as wine and food products (53,93 %), local markets and shops (26,97 %) and typical events or festivals (19,10 %).

Collected data show that the main motivation for the tourists who wish to return is the desire to relive the positive experience generated by the contact with typical local wine and food products. As pointed out by the literature, heritage tourism is related to the presence of gastronomic opportunities, as these are capable of conveying the history of the place thus enhancing traditions, practices and culture. Food and wine festivals contribute to form tourist destinations where it is easier to find and live social and communicative relationships that strengthen the bonds and the sense of community (Warde and Martens, 2000). A further important reason in relation to the desire to return is the pleasure to relive the experience generated by the contact with typical local economic realities (local markets, craftsmanship), despite the smaller number of quotations compared to the first motivation.

| Motivations to return | Number of quotations | Percentage value |

|---|---|---|

Reliving the positive experience generated by the contact with typical local wine and food products |

48 |

53,93% |

Reliving the positive experience generated by the contact with typical local economic realities |

24 |

26,97% |

Reliving the positive experience generated by the contact with typical local events |

17 |

19,10% |

TOTAL |

89 |

100% |

Source: Our elaborations.

Wine and food traditions and typical economic realities represent the most important motivations for the desire to return, and it is interesting to notice how both motivations are connected with emotional and personal involvement, combined with the feeling of taking part in the visited place (Hall and Zeppel, 1990).

An important result of this research is to have highlighted the main reasons behind the desire to relive the tourist experience. In fact, the chapter allows entrepreneurs who are concerned with heritage tourism to understand how the presence of typical wine and food products and typical local economic realities has a positive impact on the tourist experience evaluation and on the desire to return.

These facts are important to raise awareness both in the cities dealt with by the study (Florence, Naples, Rome and Venice) and in other tourist destinations. This work is in fact able to increase the knowledge of drivers and relevant reasons for the purposes of the evaluation of intangible elements of the heritage tourist experience. Tourist destinations can be considered as a set of different offers available for the visitor (Buhalis, 2000), which, often due to the large number and various types of operators require a greater coordination with respect to development and marketing policies (Buhalis, 2000). This function of coordination is often carried out by public institutions that play a key role in territory development policies thanks to local marketing actions, although not controlling the different operators in the area (Golinelli and Simoni, 2011).

It is crucial to fully understand what the interests and the feelings of the visitors are in order to produce a more detailed and clear segmentation of tourism demand. Such segmentation allows local marketing managers to carry out more targeted marketing operations, catching the attention of a wider and more heterogeneous public of potential visitors.

Conclusions

In this work, heritage tourism experiences in four different Italian cities have been analysed by means of netnographic research, which allowed the analysis of stories available on the web. This research took advantage of the traveller’s attitude to narrative (McCabe and Foster, 2006), searching in travelogues for information that can be used to understand how individuals evaluate the tourist experience as a whole. In this chapter, holidays are not considered just as a simple set of goods and services provided to visitors, but they are examined in an experiential context. Through the story, the visitor-narrator describes activities and events that characterized her/his holidays, but s/he also communicates and shares thoughts, desires, sentimental and emotional motivations and assessments regarding the place. Thanks to the introspective dimension of the examined stories it was possible to find out not only what elements of living heritage (intangible patrimony) left a deeper mark on the visitor, but also what are to be considered the real motivational factors for future visits. This shows that for a significant number of tourists a positive experience of heritage tourism is characterized by the capacity to create the desire or intention of coming back.

This study also highlighted the emotional, sentimental and critical element of the tourist experience in the texts, with reference to its intangible elements. It was thus possible to examine the process of interpretation thanks to which the visited object conveys its meaning by creating a relationship with the visitor pro-actively engaged by micro-entrepreneurs (Fyall, 2008).

As emerged from the research, intangible elements have a considerable relevance, becoming veritable attractions like those of tangible nature such as monuments, museums and landscapes.

The main limitation of the study is that a qualitative analysis implying a manual codification of the texts could be a problem in case of a very large data sample analysis, where the cognitive biases of the researcher might affect the study. However, these biases could be limited in compliance with all the instructions provided by the methodological literature on the subject. Furthermore, this research was limited to the cluster of Italian tourists travelling to Italy, representing the perception of the examined elements only from the perspective of these subjects.

In future researches, the objective will not be limited to analysing the travelogues of Italian travellers in Italy, but it will also expand on foreign tourists who visited Italy, in order to define more targeted marketing policies by exploiting efficiently and effectively the multitude of information that individuals freely share on the web.

References

Altheide, D.L. (1987). Reflections: Ethnographic content analysis. Qualitative Sociology, 10(1): 65–77.

Angrosino, M. (2007). Doing Ethnographic and Observational Research. London: Sage.

Arnould, E.J. & Thompson, C.J. (2005). Consumer culture theory (CCT): Twenty years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4): 868–882.

Ashworth, G.J. & Tunbridge, J.E. (1999). Old cities, new pasts: Heritage planning in selected cities of Central Europe. GeoJournal, 49(1): 105–116.

Baloglu, S. & Uysal, M. (1996). Market segments of push and pull motivations: A canonical correlation approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 8(3): 32–38.

Bansal, H.S. & Taylor, S. (2015). Investigating the relationship between service quality, satisfaction and switching intentions. In Proceedings of the 1997 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference, pp. 304–313. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Beerli, A. & Martin, J.D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3): 657–681.

Bennet, M. (1997). Heritage marketing: The role of information technology. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 3(3): 272–280.

Bird, S.E. (2002). It makes sense to us: Cultural identity in local legends of place. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 31(5): 519–547.

Boss, J.F. (1999). La contribution des élément du service à la satisfaction des clients. Revue Française du Marketing, (171): 115–128.

Brakus, J.J., Schmitt, B.H. & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3): 52–68.

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1): 97–116.

Butler, R.W. & Boyd, S.W. (2000). Tourism and parks – a long but uneasy relationship. In Butler, R.W & Boyd, S.W. (eds.) Tourism and National Parks: Issues and Implications, pp. 4–11. Chichester: Wiley.

Butler, R.W. & a cura di Hinch, T. (1996). Tourism and Indigenous Peoples. London: International Thompson Business Press.

Carù, A. & Cova, B. (2008). Small versus big stories in framing consumption experiences. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 11(2): 166–176.

Casarin, F. (2005). La soddisfazione del turista tra ricerche quantitative e qualitative. Sinergie, (66): 113–135.

Chandralal, L., Rindfleish, J. & Valenzuela, F. (2015). An application of travel blog narratives to explore memorable tourism experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 54(4): 419–429.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

Charmaz, K. & Mitchell, R.G. (2001). Grounded Theory in Ethnography, Handbook of Ethnography. London: Sage.

Chi, C.G.Q. & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29(4): 624–636.

Chung, J.Y. & Petrick, J.F. (2013). Measuring attribute-specific and overall satisfaction with destination experience. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 18(5): 409–420.

Clements, C. & Josiam, B. (1995). Role of involvement in the travel decision. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 1: 337–348.

Cova, B. (2003). Il Marketing Tribale. Milano: Il Sole 24 Ore.

Cova, B. (2008). Marketing tribale e altre vie non convenzionali: quali ricadute per la ricerca di mercato? Micro & Macro Marketing, 17(3): 437–448.

Crompton, J.L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4): 408–424.

Dann, G.M. (1981). Tourist motivation an appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(2): 187–219.

De Varine, H. (2005). Le radici del futuro: il patrimonio culturale al servizio dello sviluppo locale. Bologna: Clueb.

Elo, S. & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1): 107–115.

Faro Convention. (2005). Council of Europe framework convention on the value of cultural heritage for society. Available at: http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/EN/Treaties/Html/199.htm [Accessed December 04, 2015].

Fyall, A. (2008). Managing Visitor Attractions. London: Routledge.

Garrod, B. & Fyall, A. (2000). Managing heritage tourism. Annuals of Tourism Research, 27(3): 682–702.

Gellner, E. (1983). Nations and Nationalism. Oxford: Basic Blackwell.

Georgakopolou, A. (2006). Thinking big with small stories in narrative and identity analysis. Narrative Inquiry, 1(1): 122–130.

Giese, J.L. & Cote, J.A. (2000). Defining consumer satisfaction. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1(4): 1–22.

Gilli, M. (2009). Autenticità e interpretazione nell’esperienza turistica. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Giraldi, A. & Cesareo, L. (2014). Destination image differences between first-time and return visitors: An exploratory study on the city of Rome. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(4): 197–205.

Gobo, G. (2001). Descrivere il mondo. Teoria pratica del metodo etnografico in sociologia. Roma: Carrocci.

Golinelli, C.M. & Simoni, M. (2011). La relazione tra le scelte di consumo del turista e la creazione di valore per il territorio. Sinergie, (66): 237–257.

Graham, B. (2002). Heritage as knowledge: Capital or culture? Urban Studies, 39(5–6): 1003–1017.

Greene, J.C., Caracelli, V.J. & Graham, W.F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed- method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3): 255–274.

Greffe, X. (2004). Is heritage an asset or a liability? Journal of Cultural Heritage, 5(3): 301–309.

Hall, C.M. & Zeppel, H. (1990). Cultural and heritage tourism: The new grand tour? Historic Environment, 7(4): 86–98.

Hosany, S. (2012). Appraisal determinants of tourist emotional responses. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3): 303–314.

Hughes, G. (1992). Tourism and the geographical imagination. Leisure Studies, 11(1): 31–42.

Jedlowski, P. (2000). Storie comuni: la narrazione nella vita quotidiana. Milano: Pearson.

Josiam, B.M., Smeaton, G. & Clements, C.J. (1999). Involvement: Travel motivation and destination selection. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 5(2): 167–175.

Kelly, C. & Thrift, R.K. (eds.) (2009). Heritage. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, pp. 91–97. Oxford: Elsevier.

Kozinets, R.V. (1998). On netnography: Initial reflections on consumer research investigations of cyberculture. Advances in Consumer Research, 25(1): 366–371.

Kozinets, R.V. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(1): 61–72.

Kozinets, R.V. (2006). Click to connect netnography and tribal advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(3): 279–288.

Kozinets, R.V. (2015). Netnography: Redefined. London: Sage.

Laws, E. (1998). Conceptualizing visitor satisfaction management in heritage settings: An exploratory blueprinting analysis of Leeds Castle, Kent. Tourism Management, 19(6): 545–554.

Lennon, J.J. & Foley, M. (1999). Interpretation of the unimaginable: The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C., and dark tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 38(1): 46–50.

Longo, M. (2006). Sul racconto in sociologia. Letteratura, senso comune, narrazione sociologica. Nómadas. Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas, 14(2): 210–223.

Maffesoli, M. (2004). Il tempo delle tribù: il declino dell’individualismo nelle società postmoderne. Milano: Guerini e Associati.

McCabe, S. & Foster, C. (2006). The role and function of narrative in tourist interaction. Annals of Tourism and Cultural Change, 4(3): 194–215.

McCabe, S. & Stokoe, E.H. (2004). Place identity in tourist’ accounts. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3): 601–622.

Merchant, A. & Rose, G.M. (2013). Effects of advertising-evoked vicarious nostalgia on brand heritage. Journal of Business Research, 66(12): 2619–2625.

Neuendorf, K.A. (2002). The Content Analysis Guidebook. London: Sage.

Poggi, B. (2004). Mi racconti una storia? Il metodo narrativo nelle scienze sociali. Roma: Carrocci.

Poria, Y., Butler, R. & Airey, D. (2003). The core of heritage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1): 238–254.

Poria, Y., Butler, R. & Airey, D. (2004). Links between tourists, heritage, and reasons for visiting heritage sites. Journal of Travel Research, 43(1): 19–28.

Prayag, G. & Ryan, C. (2011). The relationship between the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors of a tourist destination: The role of nationality – an analytical qualitative research approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(2): 121–143.

Prentice, R.C. (1993). Tourism and Heritage Attractions. London: Routledge.

Ranfagni, S., Guercini, S. & Crawford Camiciottoli, B. (2014). An interdisciplinary method for brand association research. Management Decision, 52(4): 724–736.

Richards, G. (1996). Production and consumption of European cultural tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2): 261–283.

Rispoli, M. (2001). Prodotti turistici evoluti: casi ed esperienze in Italia. Torino: Giappichelli.

Rust, R.T. & Zahorik, A.J. (1993). Customer satisfaction, customer retention, and market share. Journal of Retailing, 69(2): 193–215.

Saldaña, J. (2012). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (Vol. 14). London: Sage.

Sherry, J.F. (1995). Contemporary Marketing and Consumer Behavior. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sims, R. (2009). Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(3): 321–336.

Solomon, M., Bamossy, G. & Askegaard, S. (1999). Consumer Behaviour: A European Perspective. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall Europe.

Swarbrooke, J. (1994). The future of the past: Heritage into the 21th century. In Seaton, A.V. (ed.) Tourism: The State of Art, pp. 222–229. Chichester: Wiley.

Swarbrooke, J. (1996). Understanding the tourist: Some thoughts on consumer behaviour research in tourism. Insights, (November): 67–76.

Szymanski, D.M. & Henard, D.H. (2001). Customer satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 2(1): 16–35.

Tilden, T. (1977). Interpreting Our Heritage. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Timmermans, S. & Tavory, I. (2007). Advancing Ethnographic Research through Grounded Theory Practice, Handbook of Grounded Theory. London: Sage.

Tussyadiah, I.P. & Fesenmaier, D.R. (2007). Interpreting tourist experiences from first person stories: A foundation for mobile guides. The 15th European Conference on Information System, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen.

Ulusoy, E. (2015). Revisiting the netnography: Implications for social marketing research concerning controversial and/or sensitive issues. In Marketing Dynamism & Sustainability: Things Change, Things Stay the Same, pp. 422–425. London: Springer International Publishing.

UNESCO. (1972). Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO.

Urry, J. (1995). Lo sguardo del turista. Roma: Edizioni SEAM.

Vecco, M. (2010). A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 11(3): 321–324.

Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2): 349–370.

Warde, A. & Martens, L. (2000). Eating Out: Social Differentiation, Consumption and Pleasure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wong, I.A. & Dioko, L.D.A. (2013). Understanding the mediated moderating role of customer expectations in the customer satisfaction model: The case of casinos. Tourism Management, 36: 188–199.

Worthington, R.L. & Whittaker, T.A. (2006). Scale development research a content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(6): 806–838.

Yang, J., Gu, Y. & Cen, J. (2011). Festival tourists’ emotion, perceived value, and behavioral intentions: A test of the moderating effect of festivalscape. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 12(1): 25–44.

Yoon, Y. & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1): 45–56.

Young, M. (1999). The social construction of tourist place. Australian Geographer, 30(3): 373–389.