3

BEING A LENDER NOT A BORROWER: THE BOND MARKET

“Debt is one person’s liability, but another person’s asset.”

—Paul Krugman, American economist

As you saw in Chapter 2, investing in stocks has considerable upside. It sounds exciting because you’re a part owner of a firm. Bonds sound dull and boring by comparison, more like an investment your parents might own. Many people share this view about bonds. The truth is quite different – many types of bonds are available to fit diverse investment styles. Perhaps surprisingly, the bond market is much larger than the stock market. Although bonds don’t get the same amount of media attention as stocks, they can provide steady income and are usually considered safer investments than stocks. Savvy investors realize the benefits of bonds, which are a good complement to equities in their investment portfolio.

“Simply put, investors should own less equities, more bonds, more global investments, more cash and more dry ammunition.”

Mohamed El-Erian

As an analogy, many Americans are homeowners but struggle to pay their mortgages. If you are a homeowner with a mortgage, you’ve probably thought about all that interest you’re paying to the bank. The interest you pay is the return the bank earns for lending the funds. Furthermore, the loan uses your house as collateral to protect the bank’s investment in case of foreclosure. Therefore, the bank is in a relatively safe position and sits back and collects its payments. In the worst case, it has collateral against its investment. If you can get a deal like this then lending doesn’t sound too bad, does it? Well, that’s exactly how the bond market works. As a bond investor, you’re lending money to companies, governments, and other entities and receiving interest and the return of principal on your loan. Savvy investors know it pays to be the banker!

Many types of bond investments are available, ranging from very safe to very risky. The level of risk is directly related to the quality of the borrower, also known as the issuer. Safe borrowers issue low-risk bonds with a low interest rate and riskier borrowers issue riskier bonds with a higher interest rate. Therefore, savvy investors diversify the bond portion of their portfolios by choosing from a broad, global array of sectors, each offering a distinct risk/return profile. Investing in a single bond usually requires more funds than investing in a single share of stock due to a bond’s higher price. So, most investors invest indirectly into a bond portfolio through a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) as discussed further in Chapter 5. Bonds are also a cornerstone of retirement plans and pensions plans because they provide steady income.

This chapter explains how the bond market works and discusses some basics of bond investing. There are many bond sectors available, but this chapter focuses mainly on investing directly in government and corporate bonds. Although bonds are less risky than stocks, they still have risks just like if you lend money to a friend who may forget (or choose not to remember) to pay you back. Not all borrowers repay their loans. You may have received a US government savings bond when you were a kid, now it’s time to learn about the grown-up version.

3.1. WHAT IS A BOND AND ITS MAJOR CHARACTERISTICS?

Bonds, also called fixed income, are a special type of loan. A bond issuer borrows money from the lender for a specific time period with a set repayment schedule. The amount borrowed is called the principal (face, maturity, or par value) and the interest paid is called the coupon. The term “coupon” is from the 1800s when bondholders had a coupon book. At the appropriate time, they would tear out the coupon and mail it to the issuer to receive payment. Although payments are made electronically now, the interest payment is still referred to as a coupon payment. Each bond has a stated principal, maturity, and coupon rate (interest rate). The most common denomination of bonds is $1,000. Additionally, issuers typically pay the coupon every six months. In this respect, bonds are similar to mortgages and auto loans where the lender knows in advance the number of payments, payment amount, and when they will occur. Thus, a bond investor usually receives a fixed coupon payment every six months over the bond’s life and then receives the principal at maturity.

“Don’t forget: Bankers may not mature, but debt matures.”

Lloyd Blankfein

Consider the following example. Walmart issues a 30-year, 8%, semi-annual bond at par. The investor lends the par value ($1,000) today to Walmart in exchange for the bond and expects to receive 60 payments (30 years × 2 payments per year) of $40 (8% ÷ 2 × $1,000) every six months for 30 years. After 30 years, the bond matures and Walmart returns the par value ($1,000) to the investor (lender). Since the largest cash flow occurs at the end of the bond’s life, the bond payment structure is called a bullet. In contrast, mortgages and auto loans are amortizing loans, which are loans that repay the amount borrowed (principal) over time. Due to the bullet structure of most bonds, they’re considered non-amortizing loans.

An important feature of bonds is that bondholders have priority over shareholders. Therefore, issuers pay coupons to bondholders before they pay dividends to shareholders. In the event of bankruptcy, the issuer’s assets are liquidated and distributed to bondholders first, although funds are probably insufficient to pay all bondholders. Some bonds are secured by specific assets called collateral, but most bonds are unsecured.

3.2. HOW DO BONDS AND LOANS DIFFER?

Bonds and loans are both considered debt but have several important differences. They’re both borrowings from different sources. Loans are direct borrowings from a single lender, typically a bank like Wells Fargo or Bank of America. Bonds are borrowings from many bondholders. Loans are private arrangements with little disclosure about the terms and are considered private debt. By contrast, bonds are considered public debt. Therefore, much more information is available about the lending relationship including the amount, interest rate, timing, seniority, collateral (if any), and restrictions known as covenants. In the event of financial trouble, negotiating with a single bank is much easier than with many bondholders who don’t know each other. Finally, investors can generally buy bonds, but not loans, as investments.

3.3. WHY INVEST IN BONDS?

“Every portfolio benefits from bonds; they provide a cushion when the stock market hits a rough patch.”

Suze Orman

In short, bonds provide safety and predictability in the form of capital preservation. They’re attractive investments because of the steady stream of coupons. Since bonds have higher priority than equity, they’re less likely to drop in value as much as stocks can. Thus, investors view bonds as relatively safe investments. For certain bonds issued by municipalities, known as municipal (muni) bonds, the interest is tax-exempt.

Bonds tend to move in the opposite direction of stocks and provide diversification to the investor. For example, during periods of economic expansion, bond prices tend to decline while stock prices tend to rise as investors are competing for capital. When stocks rally and the risk seems justified, some investors move out of bonds and into stocks, driving stock prices up further. In some circumstances, stocks and bonds can go up at the same time. Furthermore, since bonds have maturity dates, they enable investors to time their investments with anticipated expenses or purchases.

3.4. WHO ARE THE PRIMARY ISSUERS OF BONDS?

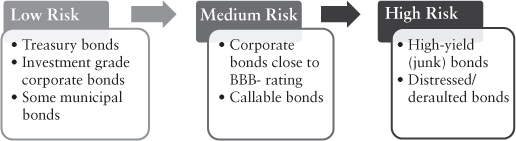

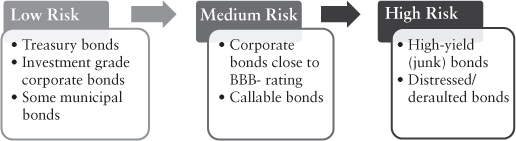

The three main issuers of bonds are federal governments, local governments, and corporations. In the United States, the largest and most frequent issuer of bonds is the US Treasury whose securities are referred to as Treasury bonds, Treasury securities, or simply Treasuries. State, city, and local municipalities also issue bonds called public finance or munis for short. Bonds issued by governments, such as Canada or the United Kingdom, are known as sovereign bonds. In fact, most of the world’s governments issue some type of bonds. These sovereign bonds may be issued in the issuer’s domestic currency or in some other currency ($US is common). Finally, corporations issue bonds to fund their growth initiatives and perhaps repay (refinance) higher interest (more expensive) debt. Figure 3.1 shows the level of riskiness associated with various types of bonds.

Figure 3.1. Risk Level of Various Types of Bonds

This figure shows the risk level of different bond classifications.

3.5. WHO ARE THE MAJOR INVESTORS IN BONDS?

Because the standard par value of most bonds is $1,000 and corporations and governments often raise funds in the millions or billions of dollars, institutional investors are the primary investors in bonds. Institutional investors are large investors such as pension funds, insurance companies, and mutual funds. These investors manage large sums of capital and are big enough to dedicate the time and resources to researching and monitoring bond investments. They also have long time horizons. Institutional investors watch their investments closely and may sell the bonds in their portfolios before they mature.

Individuals also either invest in bonds directly through a broker or buy parts of them indirectly through a mutual fund or ETF. Wealthy individuals often buy muni bonds because of their tax advantages. As individuals get closer to retirement, they often sell stocks and buy bonds because bonds are more stable in value and provide higher income. Thus, bonds are often associated with retired persons who depend on stable cash flows (interest payments) and want to avoid stock market volatility. Savvy investors needing income would rather relax on the beach with steady coupons than worry about stock market crashes.

3.6. WHAT ARE THE RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH BOND INVESTING?

Although bonds are safer than stocks, they still involve various types of risk. The most important risks are default risk (credit risk), interest rate risk, liquidity risk, reinvestment risk, and inflation risk.

“Successful investing is about managing risk, not avoiding it.”

Benjamin Graham

Credit risk. The most obvious risk, as with all loans, is getting repaid. As you’d expect, the chance of default always exists. In the event of default, the investor doesn’t receive the remaining coupons or the par value. However, some borrowers are extremely reliable, like the US Treasury, so market participants consider Treasury securities as a proxy for a risk-free security. Some companies, such as Sears and Toys “R” Us, have declared bankruptcy and won’t be paying back all of their loans. Foreign governments have also defaulted on their obligations. Since 2012, Argentina, Venezuela, Greece, and other countries have reneged on paying back their loans.

“It’s sort of like a teeter-totter; when interest rates go down, prices go up.”

Bill Gross

Interest rate risk. Another important risk for bond investors is interest rate risk or price risk. One advantage of bonds is the predictability of the coupons – investors receive the same amount every payment period because the coupon rate is fixed. However, when interest rates in the economy change so do bond prices. For example, when interest rates rise, new bond issues have a higher coupon payment and are thus more attractive than existing (previously issued) bonds with lower coupons. To adjust, existing bond prices must fall. Thus, bond prices change because of interest rate changes in the economy. This creates capital gains or capital losses in the bond market.

“Inflation is taxation without legislation.”

Milton Friedman

Inflation risk. The fixed coupon feature is also a disadvantage as the purchasing power of the fixed coupons decreases over time with inflation. Inflation is the general increase in prices most commonly measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Imagine you receive a 5% raise but inflation is 3%. Your increase in real purchasing power (adjusting for inflation) is only 2 percentage points. Still, 2 percentage points is better than nothing, but it’s much less than the 5% raise. The same holds true with fixed coupons.

“Liquidity is oxygen for a financial system.”

Ruth Porat

Liquidity risk. An additional risk to consider is liquidity risk. Liquidity measures the ability to sell an asset quickly without much loss of value. For example, equity securities are highly liquid (online trades are completed in less than one second), while real estate is illiquid (even quick real estate transactions take weeks or months). As a general rule, equities are more liquid than bonds. Bonds trade less often and trade in greater denominations. Therefore, if you need to sell your bonds quickly, you may have to accept a lower price for the quick transaction. Although the lower price is fair for the party buying the bonds, it hurts your bottom line when selling your bonds. If you hold bonds until maturity, then liquidity risk is not a concern. As a final note, bond mutual funds and ETFs are much more liquid than individual bonds.

“In investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable.”

Robert Arnott

Reinvestment risk. Bond investments tend to have very long horizons. Therefore, the coupons that are received may have to be reinvested at potentially less attractive rates. Since interest rates vary, the return the investor receives on the coupons is unknown. This uncertainty in future interest rates illustrates reinvestment risk. Of course, reinvestment risk is more important when the par value is received since it’s a much larger amount than the coupons. However, investors who use the coupons as they’re received don’t face reinvestment risk until receiving the principal.

Additional risks. Bondholders face other risks, particularly if the bond has special features. For example, the bond may pay coupons in a foreign currency, which would have to be exchanged for US dollars. The coupons may increase or decrease with interest rates and become less predictable. You can exchange some bonds, called convertible bonds, for common stock. Other bonds, referred to as callable bonds, may be retired early. Novice investors should avoid investing in such bonds until they have gained more investing experience.

3.7. WHAT IS A CREDIT RATING AND WHAT DOES IT INDICATE?

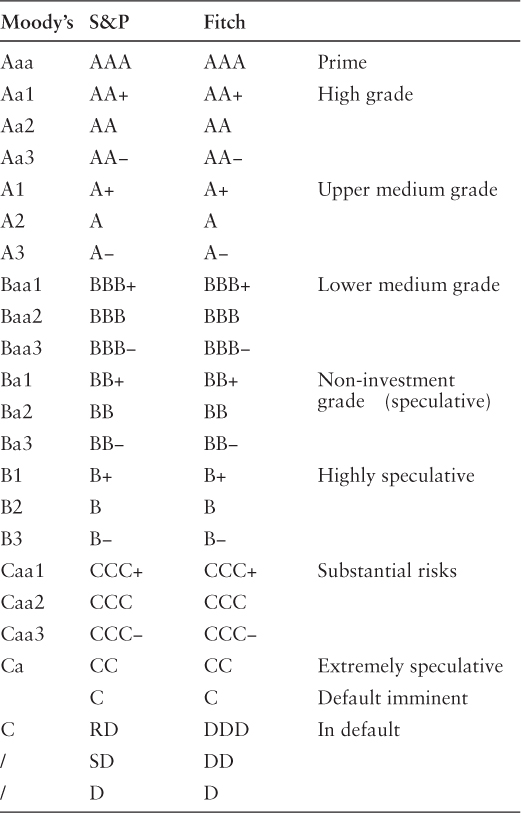

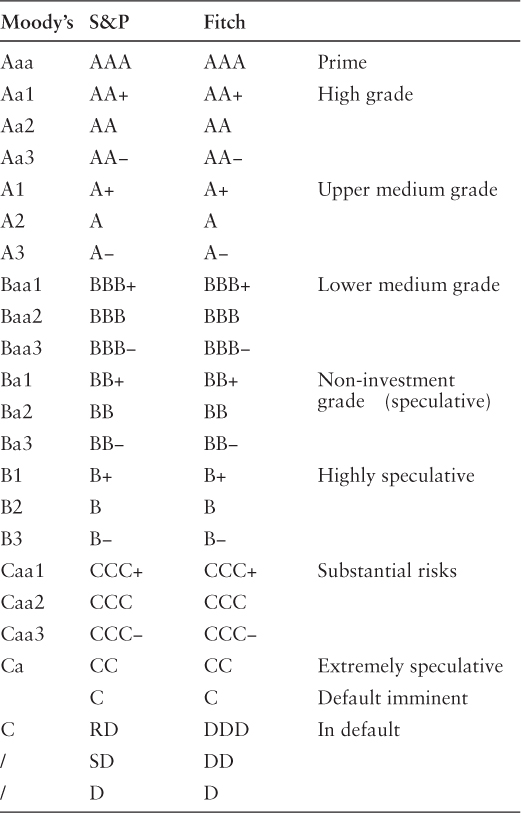

Credit ratings for bonds are like credit scores for individuals – the higher the credit rating (or score), the more creditworthy the borrower. Credit ratings give the investor an idea of how likely a bond is to default. There are three major credit rating agencies − Standard and Poor’s (S&P), Moody’s, and Fitch Ratings – and about 30 smaller ones. These companies review the financial statements, economic outlook, and other factors to determine the assigned rating. The ratings are similar to grades on an exam: A is better than B, and B is better than C, and no one wants a D (default). Each rating can be notched up or down slightly (± for S&P and Fitch, 1 and 2 for Moody’s). For practical purposes, their rating systems are highly similar and presented in Table 3.1. S&P and Moody’s use the same ratings, while Moody’s is very close. For example, Aa1 is same as AA+. Ratings of BBB− or higher are considered “investment grade” with a low chance of default, while ratings below BBB− are considered “speculative,” “high yield,” or “junk.” The rating agencies provide publicly available ratings for corporate borrowers, sovereign borrowers, and municipal borrowers. Although the ratings are imperfect, they’re general indicators of a bond’s default risk and they’re free! Savvy investors should review the credit rating before investing in any bond.

Table 3.1. Credit Ratings

The bond ratings used by the Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, and Fitch are presented below.

3.8. WHAT IS THE TREASURY YIELD CURVE AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

In simple terms, yield is the interest rate or return on a loan or bond. A yield curve is a graph of the relation between interest rates (yields) and maturity dates (length of a loan). You’re probably aware of different interest rates for mortgages, credit cards, student loans, and advances against your paycheck. The most important interest rate is the rate at which the US Treasury borrows because it’s the lowest interest available at each maturity since the US government is assumed to always pay its debts. This so-called Treasury yield curve serves as a benchmark to compare against other interest rates.

You should be aware of the four basic shapes of the yield curve.

Normal yield curve. The most common yield curve shape, called normal, is upward sloping. That is, longer loans (maturities) require higher interest rates to compensate for the additional risk.

Flat yield curve. The yield curve may be flat for brief periods of time, implying that the borrowing rate for each maturity is about the same.

Inverted yield curve. The yield curve may be inverted (downward sloping), indicating that short-term rates are higher than long-term rates. An inverted yield curve usually indicates high short-term inflation and forecasts an economic slowdown or recession in the future.

Humped yield curve. The yield curve may be hump-shaped (think of an inverted “U” shape) with lower rates in the short term and long term.

3.9. HOW DO CHANGES IN INTEREST RATES AFFECT BOND PRICES?

Bond prices and interest rates have an inverse relation. When interest rates increase, bonds prices fall, and when interest rates fall, bond prices typically rise. Why? Think about the relation in this way. Imagine you invest $1,000 today and buy a bond at par that pays a 5% annual coupon and matures in 10 years. Suppose that on the next day, interest rates rise to 6%. If you had waited, you could have invested your money and earned an additional 1 percentage point. It may not seem like much, but over the bond’s life, the 1 percentage point difference in interest rates translates into higher returns. To sell your 5% bond, you would have to provide a discount to the buyer to offset the advantage of the new 6% bonds. When interest rates increase, bonds fall in value because they’re now less attractive relative to other bonds in the market, which will be issued with higher coupons. Yet, when interest rates fall, existing bonds become more attractive because they provide higher interest over the bond’s life.

3.10. HOW DO YOU INVEST IN BONDS?

Like equities, bonds are first issued through an initial public offering, but such bond offerings don’t get nearly the attention that stocks do. In fact, Treasury bonds are issued on a regular basis and so frequently that the Treasury has an auction method in place. Only large institutions known as primary dealers that buy millions of dollars of Treasury securities participate at this stage. These dealers submit competitive bids where the winner receives an allocation of bonds with the highest price (i.e., lowest interest rate). This system might seem strange that the winner pays the most, but the Treasury’s goal is to pay the lowest interest rates. Alternatively, investors can submit noncompetitive bids and accept the rate determined at the auction. After issuance, these bonds trade in secondary markets where smaller investors can buy them. In contrast, an investment bank helps corporations issue bonds. The investment bank helps line up buyers in the premarket and receives a fee for its services. Individual investors can buy the bonds in the secondary market through a broker or online trading platform.

Many individuals buy bonds indirectly through a mutual fund or ETF. These structures provide liquidity and diversification to the investor. The investor has a claim to a fraction of many bonds based on a proportionate share of the underlying bond pool. Fees are associated with mutual funds and ETFs, but the ease of buying and selling far outweighs these costs for small investors.

3.11. HOW DO YOU MEASURE A BOND INVESTMENT’S RETURN?

Measuring a bond’s return can be tricky because the investor periodically receives fixed coupons and a bond’s price changes almost every day. Additionally, a bond is a multi-period investment because it pays interest payments every six months, but it’s customary to report returns on an annual basis. Two common measures of bond returns are current yield and yield to maturity (YTM). Current yield is the annual coupon divided by the bond’s price, which represents the short-term percentage return on the investment. For example, if an investor purchased a bond for $980 with annual coupon rate of 6%, the current yield would be $60/$980 = 6.1%. Savvy investors recognize that a bond’s price can change daily but approaches par value by maturity, so it’s not the most accurate measure. That is, the current yield in each year can change.

“It all comes down to interest rates. As an investor, all you’re doing is putting up a lump-sum payment for a future cash flow.”

Ray Dalio

The YTM is a more common method. The name almost tells it all. YTM is the promised return (yield) if the bond is held until maturity and redeemed for par value. If the investor sells the bond before maturity, the bond defaults, or the issuer calls the bond, then the bond’s actual return is likely to differ from its YTM. You should note, however, that YTM is an approximation of the bond’s return. Why? This method assumes the coupons received are reinvested at the same rate, namely the YTM, over the investment horizon, which is highly unlikely because interest rates often change. Basically, the YTM calculation assumes the yield curve is flat. Nevertheless, the YTM is quoted frequently and captures the essence of a bond’s return if held to maturity.

3.12. WHAT ARE BOND QUOTES AND HOW DO YOU READ THEM?

A bond quote denotes the current price of the bond. Although this seems like a simple concept, several ways are available to quote a bond’s price. First, bonds are often quoted as a percent of par value ($1,000). So, a bond trading at 99 is really 99% of par value or $990. In this case, the bond is called a discount bond because it is priced less than its par value. A bond trading at 105.5 has a price of $1,055 and is called a premium bond because its price is at a premium to par. Second, a bond may be quoted based on its yield. Therefore, a bond with a YTM of 4% is expected to return 4% per year assuming a constant reinvestment rate as discussed in the previous question. This quotation method is simple and intuitive but does not indicate the current price, maturity, or coupon. Third, bond prices may be quoted as a spread relative to a benchmark. The most common benchmark to use is a maturity-matched US Treasury. Suppose a 5-year corporate bond is quoted with a spread of 120 basis points where 100 basis points = 1%. This quote indicates that the corporate bond has a yield of 1.2% (120 basis points) higher than a 5-year US Treasury. If the 5-year Treasury’s yield is 1.7%, the corporate bond is yielding 2.9%.

3.13. HOW DO BONDS TRADE?

Unlike the exchanges where many stocks trade, no centralized location exists for bond trading. Bonds usually trade over-the-counter, which is a loosely connected market of dealers who communicate electronically. The market is similar to a large, online garage sale where the sellers are bond dealers or trading desks of major investment banks. A few bonds and bond-related products trade on stock exchanges. Although the trading volume for Treasury securities is high, the trading of corporate and muni bonds is comparatively sparse. For individual investors whose purchases are relatively small, using a broker or online trading platform is sufficient.

3.14. WHAT ARE THE TAX LIABILITIES OF BOND INVESTMENTS?

Answering this question can be tricky because different investors face their own unique tax situations. In fact, certain institutions such as foundations, endowments, and not-for-profits don’t pay taxes. But, in general, investors pay taxes on the coupons received, and this amount is considered ordinary income. An investor who sells a bond before maturity may incur additional taxes. Suppose you buy a bond at a discount due to rising interest rates for $900 and then sell it for $950 two years later. This transaction is considered a capital gain (sold above the purchase price) and taxes are due on the $50 difference. If the capital gains tax rate is 20%, you would owe $10 (= 20% of the $50 gain). In the United States, capital gains taxes are lower than taxes on ordinary income. Alternatively, if you sell the bond for $860, you would experience a capital loss (sold below the purchase price). The $40 loss would reduce taxable income in the year of the sale and would lower your tax bill by $8 (= 20% of the $40 loss).

“The avoidance of taxes is the only intellectual pursuit that still carries any reward.”

John Maynard Keynes

Of more importance is the coupon tax treatment because a major reason for buying a bond is to receive steady, predicable interest payments. Unfortunately, the coupons are taxed at the investor’s marginal tax rate, which is often higher than the capital gains rate. However, you should be aware of two noteworthy exceptions:

Treasury bonds are exempt from state and local taxes but are taxable for federal purposes.

Municipal bonds are tax-exempt from federal taxes and tax-exempt if purchased from the state of residence. For this reason, munis are sometimes referred to as “triple tax free” investments.

Overall, the tax treatment for bonds is more complicated than for stocks. For example, an investor may buy a bond while working (high tax bracket) but collect coupons and principal while retired (lower tax bracket). Furthermore, consider that an individual may be better off purchasing a low-yielding municipal bond that is tax-exempt compared to a higher yielding corporate that is taxable. This statement is particularly important for those who face a higher marginal tax bracket. Savvy investors try to minimize their tax bill. For example, a taxable investor is considering a 5% taxable corporate bond and a 4% municipal bond. If the investor’s tax rate is 24%, then the after-tax yield on the corporate bond is 3.8% (= 5% × (1 − 24%)) which is lower than the 4% municipal bond yield. Therefore, the municipal bond provides the higher after-tax return despite the lower nominal yield.

3.15. WHAT HAPPENS IF A BOND DEFAULTS?

A bond is considered in default if the issuer misses a coupon payment, fails to repay principal, or files for bankruptcy. Although you may occasionally hear about a bailout by the Federal government, don’t count on that! Bonds that default still trade but at a steep discount to par, such as 20 cents on the dollar. Sophisticated investors called vultures or distressed debt investors may buy the bonds on the cheap hoping for a recovery or restructuring. However, ordinary investors must be patient. They must wait for the assets to be liquidated (Chapter 7 bankruptcy) or for the debt to be restructured (Chapter 11 bankruptcy), which often involves the bankruptcy court. In other words, the recovery amount is uncertain and could take years. In some cases, the issuer may replace defaulted debt with new equity shares or with new bonds but, in either case, the value would be less than the original debt.

3.16. WHAT ARE CALLABLE AND CONVERTIBLE BONDS?

Two notable characteristics of some bonds are call and convertible features. These features are a type of embedded option, which is a bond component that usually gives the issuer or the bondholder the right to take some action against the other party. The terms and conditions involving callable bonds and convertible bonds are found in the bond indenture, which is a legal and binding contract between a bond issuer and the bondholder.

Callable bonds. A callable bond is a debt instrument that gives the issuer the right to repurchase the debt before its maturity at a prespecified price and date. If the issuer calls a bond, then investors must give up their bonds and receive the prespecified call price, usually the par value plus a small premium such as one year of interest payments. Callable bonds are a more sophisticated type of bond where the issuer has the right or option, but not the obligation, to retire the bond before its normal maturity. Because this right to pay off the debt is valuable to the issuer, investors usually require a higher interest rate to compensate them for buying these riskier callable bonds.

Callable bonds usually have a period of call protection in which the issuer can’t call the bond. During this period, investors earn higher interest rates. Why would an issuer want to call a bond? The bond issuer would do it for the same reason that a homeowner would refinance a mortgage – that issuer or homeowner wants to reduce the size of the payments. When interest rates fall, the bond issuer would prefer to pay the lower interest rate. A callable bond gives the issuer the opportunity to refinance the borrowings if interest rates decline. Recall the earlier discussion on reinvestment risk. Investors in callable bonds face reinvestment risk because an issuer is likely to call the bonds after interest rates sufficiently drop. The issuer can then issue new bonds with lower coupons than the called bonds.

Convertible bonds. A convertible bond is another example of a nonstandard bond. These bonds are hybrid instruments between debt and equity because they offer the downside protection of a bond with the upside potential of a stock. A convertible bond is a financial instrument that gives the investor the right or option to exchange the bond for a prespecified number of shares in the issuing company. Like a regular bond with no special features, convertible bonds pay interest and mature at a predefined date. When the company’s stock price underperforms, investors in a convertible bond still benefit from the stability of the bond itself, receiving regular coupons and principal at maturity. However, when the stock increases, the ability to convert the bond into shares offers investors an upside opportunity beyond a regular bond.

Why would a company issue convertible bonds? For many issuers of convertible bonds, access to the normal bond markets may be difficult or may require prohibitively expensive interest rates. The most common issuers of convertible bonds are start-up companies and other younger firms that are focused on growing revenues and need capital to support their growth initiatives. Issuing standard or straight bonds would require regular interest payments (usually at high rates given the company’s unproven cash generation capabilities), which the company may be reluctant to undertake. Although convertible bonds pay interest, the interest rate is typically lower than the prevailing rate at the time of issuance because the company is simultaneously offering investors the chance to participate in its potential upside via equity.

3.17. WHAT ARE GREEN BONDS?

A green (climate) bond is a bond that tries to improve efficiency and support environmental initiatives. These bonds raise funds to improve the energy efficiency of existing structures (brownfield developments), build new, sustainable infrastructure (greenfield developments), develop clean transportation, sustainable agriculture, and other similar initiatives. Green bonds often have tax incentives such as tax credits and/or tax exemptions. This market segment has been growing rapidly and allows the investor not only to earn a return but also to make an environmental contribution.

3.18. WHAT ARE TREASURY INFLATION-PROTECTED SECURITIES?

Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) are Treasury bonds that compensate the investor for changes in inflation over the bond’s life. A primary concern for bond investors is that inflation reduces the purchasing power of future coupons and principal. TIPS change the value of the principal over time depending on inflation. This inflation-adjusted principal affects the size of the coupons and the payment at maturity.

“Inflation is as violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hit man.”

Ronald Reagan

3.19. WHAT ARE ASSET-BACKED SECURITIES?

Asset-backed securities are pooled investments based on mortgages, auto loans, student loans, credit card receivables, and similar items. These pools issue bonds based on the inflows to the pool called the collateral. An important feature of these pools is that the cash flows are often carved into different tranches, each with its own risk and return. A tranche, which is French for slice, is a group of similar bond instruments within a larger debt issue. Each part or tranche is characterized by a unique set of features such as maturity, interest (coupon) rate, and interest payment date to suit the needs of different investors. Although the total risk to the pool is unchanged by tranching, investors can buy into the higher-rated (safer, low return) or lower-rated (riskier, high return) tranches as they desire. The largest segment of this market is based on mortgages where the primary issuers are Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae), Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac). Because these investments have their own unique risk factors, they are best left to experienced investors.

As you’d expect, these pooled instruments are less transparent and harder for investors to analyze relative to fixed coupon bonds. They require more faith in the issuer and credit rating agencies to perform their due diligence. Unfortunately, the financial crisis of 2007–2009 was partly a result of underestimating the risk of these securities. The recession that ensued affected the overall economy and prompted new regulations including the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, or more simply Dodd-Frank. Dodd-Frank imposed sweeping changes in financial regulation to protect consumers and investors and restrict the speculative investments by banks.

“Forced to confront a reptile or an international financial crisis, I’ll take the reptile every time.”

Alexandra Petri

3.20. HOW DO YOU INVEST IN A PORTFOLIO OF BONDS?

Answering this question mainly depends on the amount of funds available to invest. Large institutional investors with considerable capital can research and identify bond issues that they deem attractive. Individual investors with a relatively small amount of money to invest are much more likely to buy a proportionate share of a pool of bonds using a bond mutual fund or bond ETF. Most 401(k) and 403(b) plans offer a bond option, which is likely a bond mutual fund. For more experienced investors, many bond funds and ETFs invest in a narrow part of the fixed income market. You can invest in short- or long-term government bonds, short- or long-term municipal bonds, investment grade corporate issuers, speculative issuers, or issuers in a particular sector such as transportation. For example, a savvy investor living in California might seek a bond mutual fund that focuses on municipal bonds from California. Thus, the interest income from the mutual fund would be tax-exempt from both federal and state income taxes. You can diversify into sovereign debt or bonds with more risk and hopefully return such as convertible bonds.

3.21. WHAT ARE SOME BOND INVESTING STRATEGIES?

As you might expect, various bond investing strategies are available. Here are a few of them.

Buy-and-hold strategy. The most common strategy for many investors is the long-term buy-and-hold strategy. Because the investor intends to buy the bond and hold it until maturity, this “set-it-and-forget-it” approach barely qualifies as a strategy. Yet, it’s appropriate if you plan to spend the coupons as received, which makes sense for retirees who want predictable income. When the bond matures and the issue returns the principal, you are likely to buy another bond and repeat the process. However, you are still exposed to both reinvestment risk and inflation risk because the coupons buy less over time.

Laddered strategy. A variation on the buy-and-hold strategy is a laddered strategy. Here, you divide your investment into bonds with different maturities such as those maturing every five years. You spend the coupons as received but reinvest the principal on maturing bonds more frequently. This approach reduces reinvestment risk by spreading out the purchases over time.

Barbell strategy. The barbell strategy is a simplified ladder strategy where the total bond principal is divided into two maturities (short and long). The short-term bonds periodically mature and need to be replaced. This strategy is relatively easy to implement and smooths out the reinvestment risk from buying the bonds all at once.

Other bond strategies. Many other strategies are best left to more sophisticated investors such as distressed debt, credit trades, and yield curve (duration) trades. With a distressed debt strategy, investors look for bankrupt companies and buy bonds in hopes of a recovery or reorganization. A credit trade is where an investor sells a bond before a company is downgraded or experiences poor performance. Similarly, an investor may buy a bond before a company is upgraded or experiences strong performance. Finally, an investor may buy or sell a bond ahead of expected changes in interest rates. For example, if interest rates are expected to rise, an investor would want to sell long maturity bonds that are exposed to high interest rate risk and buy short maturity bonds. As previously mentioned, these are more advanced bond strategies. Novices should keep their strategy simple.

3.22. WHY DO COMPANIES HAVE MANY BOND ISSUES?

Remember that companies issue bonds to raise capital, which they can use to fund various projects, buyback outstanding shares, or pay off older loans or bonds with higher interest rates or coupon rates. Thus, a firm may issue bonds at different points in time for many reasons. Managers may also issue bonds when rates are low even if they don’t immediately need the funds. Savvy investors realize that managers know more about their firm than do outsiders and may use this flexibility to borrow funds and make decisions strategically. Consider events at companies like Apple that are issuing bonds even though they have plenty of cash on their balance sheets. This seems puzzling – why borrow when a company already has sufficient cash? But the reason is subtle – multinational corporations like Apple make considerable profits from overseas sales but rather than bring the cash back to the United States and pay taxes, they choose to leave these funds overseas. Thus, the firm issues bonds to have access to the cash and pay low interest rather than pay high taxes.

3.23. WHAT COMMON MISTAKES DO INVESTORS MAKE WHEN INVESTING IN BONDS?

“I would never be 100 percent in stocks or 100 percent in bonds or cash.”

Harry Markowitz

Bond investors face several pitfalls. Perhaps the most important mistake is to underestimate the risk in corporate bonds. The US government, despite its very large debt level and budget deficit, is unlikely to default. However, even the most profitable companies can fall on hard times like Sears, General Electric, and Ford – all former titans of industry. Return of principal is not guaranteed! Additionally, if investors rely too much on bonds, their portfolio may not keep up with inflation or, at the very least, their purchasing power decreases. So, investors should be mindful to balance bonds with equities to allow for some growth in the portfolio. The tax liabilities associated with bonds are more complex based on the issuer (Treasury, muni, or corporate), size of coupon, state of residence, current income (retired or working), and other factors. Savvy investors should consult a tax expert for appropriate planning. Finally, although market experts generally consider bonds safe investments, sudden increases in interest rates can cause a bond’s price to drop considerably. But by holding bonds to maturity, they eventually return their par value.

3.24. WHAT ARE SOME INVESTMENT SITES TO HELP LEARN MORE ABOUT BOND INVESTING?

Here are some websites that provide information about bond investing.

Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (http://www2.investinginbonds.com/) is a nonprofit industry association whose mission is to strengthen financial markets and to build trust and confidence in the financial industry.

Investopedia (https://www.investopedia.com) is a leading web source of financial content that focuses on general investing, financial education, and analysis.

The Motley Fool (www.fool.com) is a financial services company that provides financial advice for investors through various stock, investing, and personal finance services.

Seeking Alpha (https://seekingalpha.com) offers a crowd-sourced content service for financial markets including articles and research covering a broad range of topics including bonds, stocks, ETFs, and investment strategies.

Investing.com provides useful up-to-date information on bond market fundamentals for the United States and foreign markets (https://www.investing.com/rates-bonds/).

The US Treasury Department provides a wealth of user-friendly data on yield curves, bond auctions, and related information (https://home.treasury.gov/services/bonds-and-securities).

The US Securities and Exchange Commission maintains the investor.gov. website (https://www.investor.gov) that provides unbiased information to help you evaluate your investment choices and protect against fraud.

3.25. TAKEAWAYS

As an investor, you will likely want to balance growth (stocks) with income (bonds) particularly as you approach and enter retirement. Therefore, bonds play an important role in your long-term financial plan. Although bonds are generally safer than stocks, they still face default risk, liquidity risk, reinvestment risk, and interest rate risk. The amount of risk depends on the issuer and current economic conditions. Thus, you need to keep your eyes wide open when evaluating the various risks associated with investing in bonds. Purchasing individual bonds has a higher per unit cost than equities because of the high par value. Despite the availability of different types of bonds, fewer strategies and choices are available than in equity markets for individual investors. The easiest way to gain exposure to the bond market is through bond mutual funds or bond ETFs. Taxes are a more important concern for bonds than stocks because you receive the coupons periodically. Your investing strategy and tax status are likely to shift as your financial situation, experience, and goals change. Here are some important lessons from this chapter.

Learn the language of bonds before investing because they’re an important part of a diversified portfolio.

Buy bonds through mutual funds and ETFs because single bonds are less liquid than stocks particularly for individual investors.

Remember that bond prices move in the opposite direction of interest rates.

Adopt a bond strategy that fits your needs. Although the simplest bond strategy is a buy-and-hold strategy, ladders and barbells are other common strategies that enable you to reduce reinvestment risk.

Be aware that the tax liabilities of bonds are more complex than stocks.

Understand that bond credit ratings estimate the borrower’s creditworthiness.

Avoid underestimating the risk of corporate bonds and the impact of inflation’s purchasing power risk.