1

WHAT WILL CLIMATE CHANGE DO TO OUR ECONOMY?

Rod Oram

HERE IN NEW ZEALAND WE WASH AWAY each year some 200 million tonnes of topsoil, the lifeblood of our economy’s primary sector, thanks to the way we use our land. The eroded soil clogs up our streams, rivers, estuaries and shallow coastal waters, smothering their ecosystems, which are crucial parts of our own life-support system.

We aren’t the worst offenders. Worldwide, we humans move more of the Earth’s surface each year than do natural processes because of the way we farm, quarry, build and reshape our environment in myriad ways.

This is truly the Anthropocene, the geological epoch in which humankind is the greatest driver of planetary change, as geologists concluded in their international congress in 2016. Natural phenomena dramatically shaped all earlier geological times in the planet’s 4.5-billion-year history to date. Of course, we too are a natural phenomenon. But we are fundamentally different from all others. We choose to do what we do. Unlike dinosaurs, we have some control over our destiny; and how we take responsibility or not for the Anthropocene now and over the next few decades will determine everything about our life on Earth, for good and ill. Since there’s no place on the planet to hide from this, even here on these specks of land at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, our life and economy will change radically here, too, in Aotearoa New Zealand. We will be much better off actively shaping our future rather than following passively in the wake of the tsunami of change.

Now we have an economy that fails to pay many a reasonable wage or meet their material needs; that is driven by unsustainable debt, production and consumption; that rapidly degrades our ecosystem on which we depend, as documented by Environment Aotearoa 2015, the government’s first comprehensive evaluation of our ecosystem. On our current trajectory, all those will get worse. But again, we are not alone. Those are the characteristics of the global economy, albeit we give our own expression to them, such as the rapid expansion of dairy farming and international tourism.

In the future, should we choose, we can have an economy that provides a high standard of living in financial and physical terms, in deeply sustainable ways; and we can do so in ways that make sense for who we are as a diverse nation founded on Treaty of Waitangi principles, for the nature of our land and oceans, and for our destiny as a distinctive, tiny country in a teeming world hungry for inspiration and innovation.

Our guide will be the planet itself, hence our need to own up to the Anthropocene. Geologists will decide over the next few years the starting date of the Anthropocene. As with their delineation of all other geological eras and epochs, they are looking for a worldwide geological marker of abrupt change that will be identifiable to intelligent life forms millions of years from now, as we have identified previous change-points. The strong front-runner is the decade or so after the detonation of the first nuclear device in 1944. The fallout of human-made radioisotopes, and subsequent explosions before the air-borne testing of nuclear weapons was banned, blanketed the Earth, creating an ideal geological marker.

The previous epoch, the Holocene, began around 11,700 years ago. Back then, Homo sapiens numbered some 2 million to 4 million people — mostly hunter-gatherers. But once the climate stabilised at the start of the Holocene, they began quickly to settle down and domesticate plants and animals, enabling longer life and faster population growth. Today, we so-named ‘wise men and women’ now number some 7.5 billion people. But we humans have only been sowing these seeds of destruction since the start of the industrial revolution 250 years ago. That’s only a scintilla of time in the life of the planet. And, astonishingly, it is only in the past 50 or 60 years that our human activity has increased so enormously that it has become planet-changing.

This Great Acceleration, with a base year of 1950, was first named in 2004 in the work of the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP). ‘The second half of the twentieth century is unique in the entire history of human existence on Earth. Many human activities reached take-off points sometime in the twentieth century and have accelerated sharply towards the end of the century. The last 50 years have without doubt seen the most rapid transformation of the human relationship with the natural world in the history of humankind,’ wrote Will Steffen and colleagues at the Stockholm Resilience Centre.1

Their work on the IGBP identified 12 socio-economic trends, and the rapid growth of them since 1950. These include human population, economic activity, urban populations, energy use, fertiliser consumption, large dams, water use, transport and international tourism. Then they showed the impact of those on 12 Earth system trends, such as: atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane (the three key climate-changing greenhouse gases); surface temperature; ocean acidification; marine fish harvesting and shrimp aquaculture; nitrogen flows to coastal zones (as a result of our use of artificial fertilisers to grow food); tropical forest loss; the rise in land domesticated; and terrestrial biosphere degradation. And the Great Acceleration has quickened since, as Steffen and colleagues reported in a 2015 paper updating their original work.2

These socio-economic trends and Earth system impacts feed on each other. ‘In a shrinking world, seemingly unrelated events can be links in the same chain of cause and effect. Nature, politics, and the economy are now interconnected,’ Johan Rockström, director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre, writes in his book Big World, Small Planet. ‘The web of life is fully connected, encompassing all of the planet’s ecosystems, and every link in the chain matters.’

A fundamental factor in this acceleration is an exponential expansion of human technological prowess. Technologies are combining to deeply disrupt our existing knowledge and practices. We are reinventing computing, energy, medicine, biology, food, farming, transport, education, work, space exploration and almost any other area of life we can imagine, even democracy itself. Getting to grips with these vast issues of utter unsustainability is daunting. One of the most helpful frameworks for doing so is the Planetary Boundaries work of Rockström, Steffen and their colleagues in Stockholm. They have calculated the ‘safe place for humanity’ within nine biophysical parameters. Once human activity passes these thresholds, or tipping points, there is a risk of irreversible and abrupt environmental change.

Our biggest global overshoots so far are loss of biodiversity, excessive phosphorus and nitrogen flows, and climate change. How we use land and grow food are the key drivers of the first two, and to a great extent the third also. Globally, agriculture, forestry and land use account for 21 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, the second-largest source after electricity and other forms of power (37 per cent) and ahead of transport (14 per cent).3

Can we continue the way we’re going? For a long while, we’ve seen the tell-tale signs we can’t.

We exemplify some of these planet-changing dynamics in our own way here in Aotearoa New Zealand. Since 1985, which was about when we began working on our current framework of environmental legislation, two species in particular have enjoyed spectacular growth: humans have increased by 40 per cent to 4.6 million; and milked cows by 120 per cent to 5 million. Both species have been highly productive. The human economy has grown six-fold to $240 billion in current dollar terms; and milk volume has trebled to 21 billion litres. Both urban and rural economies have boomed, putting increasing pressure on the ecosystem. The population of Auckland, for example, has grown by 75 per cent to 1.5 million since 1985.

Can we continue the way we’re going? For a long while, we’ve seen the tell-tale signs we can’t. Only in 2015, however, did Parliament finally pass the Environment Reporting Act. We were the last country in the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to initiate a comprehensive system of data collection and analysis to measure regularly the health of its ecosystem. The first report, Environment Aotearoa 2015, laid bare the damage we were doing to land, water, air and seas, and to the diverse species that depend on them, as we ourselves do.

Then in 2017, the OECD delivered its own verdict in its once-a-decade report on our environmental performance:

New Zealand’s growth model … has started to show its environmental limits, with increased GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions, freshwater contamination and threats to biodiversity. Addressing GHG emissions from agriculture, and especially dairy farming, should remain a priority … [along with] the need to further explore the economic opportunities that more sustainable uses could yield. Developing a long-term vision for a transition towards a low-carbon, greener economy would help New Zealand defend the ‘green’ reputation it has acquired at an international level.4

Moreover, this exploitation and degradation of our ecosystem to produce commodity products has impoverished us in many other ways. We languish at twenty-fifth in the OECD’s rankings of the 35 developed countries in GDP per capita terms, while our unaffordability of homes, our homeless population, our educational disparities, and our youth suicide rates rank among the highest in the OECD. This is our paradox of poverty amid plenty. Bar oil producers, we have per capita the highest stock of natural capital in the world; and ours is a world of ever-scarcer resources. Yet we’re struggling economically and environmentally.

This is our own local expression of a global economic system in deep trouble. Rapid advancements in technology and trade have benefited many people in developing and developed countries. But they are greatly distorting economic systems, triggering massive corrections, in particular the Global Financial Crisis and the Euro Crisis in recent years.

Many people have suffered. In 25 advanced economies two-thirds of households experienced flat or falling real incomes between 2005 and 2014, according to analysis by the McKinsey Global Institute in 2016. Some 540 million were affected, which helps explain the polarisation of politics, the shattering of societies and the backlash against immigrants in the United States and most countries in Europe.

Since many of these bewildering issues feed on each other, understanding the interdependence between them is the first step for societies seeking to work out how to respond. One guide to the linkages is the Global Risks Report produced each year by the World Economic Forum. Its latest iteration identifies 13 major risks. The biggest are climate change, rising income and wealth disparity, increasing polarisation of societies, and rising cyber-dependency, followed by degraded environments, rising urbanisation, growing middle classes in developing countries, ageing populations, increasing nationalist sentiment, changing landscape of international governance, shifting power, rising geographic mobility, and rising chronic diseases.

From these factors, the report maps a range of interconnections and impacts such as the adverse consequences of technological advancement, unemployment, fiscal crises, extreme weather events, food and water crises, large-scale involuntary migration, failure of critical infrastructure and state collapse or crisis. ‘Globally, people are enjoying the highest standards of living in human history. And yet acceleration and interconnectedness in every field of human activity are pushing the absorptive capacities of institutions, communities and individuals to their limits. This is putting future human development at risk,’ the report concludes.

Rightly, it makes no attempt to offer detailed prescriptions for progress. Diverse peoples will find the ways that are right and best for them to respond, at every scale of society from intensely local to expansively global, as we will in Aotearoa New Zealand. But it asserts that we humans cannot deal with the challenges ‘either sequentially or in isolation’, adding: ‘Multi-stakeholder dialogue remains the keystone of the strategies that will enable us to build a better world.’5

Given this is a big topic and a short essay, I’ll simply offer a set of goals, a concept for achieving them, and a quote.

First, the goals are the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by member countries in September 2015. Formally known as Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, it is a set of 17 global goals with 169 targets between them.

The Global Goals for Sustainable Development

- No poverty

- Zero hunger

- Good health and well-being

- Quality education

- Gender equality

- Clean water and sanitation

- Affordable and clean energy

- Decent work and economic growth

- Industry, innovation and infrastructure

- Reduced inequalities

- Sustainable cities and communities

- Responsible consumption and production

- Climate action

- Life below water

- Life on land

- Peace and justice, strong institutions

- Partnerships for the goals

That sounds monstrously bureaucratic. But there is no doubting the wisdom and practicality of the goals. Crucially, they are starting to focus the strategies and energies of countries, governments, multilateral institutions, multinational companies, civil society organisations and many other players down to a very local level. Here, for example, Rotorua Lakes Council, representing a district of just 65,280 people, signed up two years ago to the cities programme in the United Nations’ Global Compact. Within that, it is using the SDGs to help it with its long-term planning.

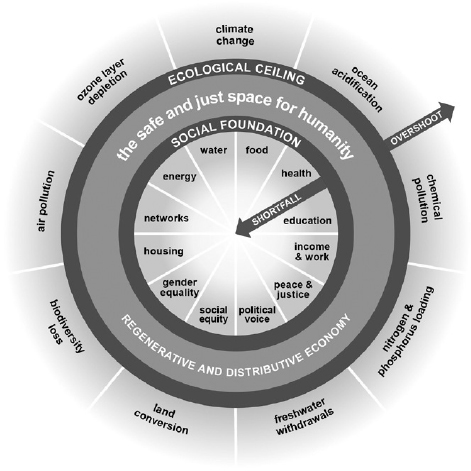

Clearly, humankind will fall far, far short of those goals by 2030 if we merely tweak what we do now. So, second, here’s a concept for how we can bring about transformative change, and fast. It’s the work of Kate Raworth, a British economist. Starting as a whiteboard doodle of two circles Kate drew in an Oxfam staff meeting in the UK a few years back, she has developed it into a powerful, insightful and encouraging body of work in her latest book published in 2017: Doughnut Economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist.6 Her central concept is simply illustrated:

Doughnut concept. Source: Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist

The outer circle is the ecological ceiling — the nine planetary boundaries of the Stockholm Resilience Centre. The inner circle is the social foundation — 12 fundamentals such as education, political voice, energy and food — that people have to have if they are to flourish and contribute to changing their communities and, as communities, contribute to global progress. Between the ceiling and floor is ‘the safe and just space for humanity’, enabled by a ‘regenerative and distributive economy’.

Raworth lays out seven big shifts we need to make:

- From defining progress as GDP growth, which is an exceptionally narrow economic metric that excludes social and environmental outcomes, to defining it as ‘meeting the needs of all within the means of the planet’.

- From narrowly defining the economy as a self-contained market to seeing it embedded in, contributing to and dependent on society and the ecosystem.

- From fixating on the ‘rational economic man’ to appreciating and responding to the diversity of human behaviours, which include interdependence, reciprocity, and adaptability to the people and circumstances around us.

- From simple supply–demand equilibrium in markets to the dynamic complexity of economies, societies and ecosystems.

- From the flawed hope that growth will reduce inequalities to ensuring that all people share in the means of creating wealth and receive their fair share of the rewards.

- From believing that growth will enable us to clean up the mess we’ve made to redesigning our use of natural resources, our products, service and economies so they contribute to the regeneration of the ecosystem.

- From addiction to endless growth to creating economies that thrive and deliver for people and the planet without necessarily growing.

In 1960, Article 1a of the OECD’s founding constitution read: ‘The aims of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development shall be to promote policies designed to … achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries.’ Today, Raworth argues, its goal should instead be ‘to create regenerative and distributive economies that enable humanity to thrive, whether or not they grow’.

These towering but enlivening goals, and this daunting but empowering framework, can guide us, here and abroad, on the long, hard road to deep sustainability. To embolden us on the journey, here is a confronting but compelling quote from Roy Scranton’s book Learning to Die in the Anthropocene:

The greatest challenge we face is a philosophical one: understanding that this civilization is already dead. The sooner we confront our situation and realize that there is nothing we can do to save ourselves, the sooner we can get down to the difficult task of adapting, with mortal humility, to the new reality.7

Many of us Kiwis want to progress, as do billions of other people around the world. We want to be wealthier in all senses of the word, economically, socially, culturally and environmentally. But we know we won’t achieve those reasonable goals by working the way we do now. Conversely, very few people believe life is as good as it gets and will continue this way for decades and generations to come.

To progress, we need a new civilisation, as Scranton argues. That sounds extremely radical. In essence, though, our civilisation is what we believe and how we behave, both of which are informed by our past, reinforced by our present and shaped by our hopes for the future. If we change one central aspect of our civilisation, our relationship with nature, we will find our cultural and societal strengths will enable us to transform this good-in-parts but unsustainable civilisation to one that is better and sustainable.

In everything we do we need to ask ourselves: how do we work with nature, not against it? If we figure that out, we will give the ecosystem, our life-support system, a chance to regenerate, and thus be more resilient and abundant. Ecosystems, though, don’t revert; they evolve. Aotearoa will not go back to a sparsely populated land blanketed by native trees, inhabited by a cacophony of native birds and surrounded by seas teeming with life. Hopefully, though, it will evolve into an hospitable ecosystem in which, say, 7 million or 8 million of us live well within its limits by mid-century.

We will have no hope, however, if we fail to play our role locally in helping people globally arrest climate change. On current global emissions trends we’re heading for rises of at least 5 °C in temperature and many metres in sea level, or more, causing devastating deterioration of the global ecosystem.

Our nation’s contributions to the global challenge of ensuring some 10 billion people are living well by 2050 vastly exceeds our tiny proportion of emissions. We have already made a highly significant one. New Zealand helped break the decades-long deadlock in global climate negotiations by suggesting each country make its own Intended Nationally Determined Contribution. This became the organising principle for the Paris climate agreement in 2015, signed by 195 of the 197 nations on the planet.

We can help ourselves, and the rest of humankind, a great deal more. We have much at stake. Arguably, we are more dependent on our natural environment for earning our living and maintaining our lifestyle than any other developed country. Not only is the ecosystem critical to the primary sector, which accounts for only one-seventh of our economy, but it also enriches many other sectors, such as tourism, creative, marine, education, biological and life sciences, in addition to the way it defines who we are as a people, and how and where we live in the South Pacific.

Our responsibilities extend far beyond our small islands and their coastal waters to the vast oceans around us. The United Nations, under its Law of the Sea, entrusts us with the fourth largest Exclusive Economic Zone on the planet. These 4,083,744 square kilometres of ocean, which is some 15 times our land area, have the highest level of endemic species and relatively the least degraded waters on the planet. In addition to the south in Antarctica, we have long taken a leading role in exploration and science, and governance under the Antarctic Treaty, which came into effect in 1961, and its related agreements.

We’re working on many of these great issues at a very high level under the 11 National Science Challenges initiated by the Key Government. Of these 10-year programmes, seven focus directly on ecosystem resilience (land and water, biodiversity, sustainable seas, high value nutrition, urban environment, natural disasters, Antarctica and the Southern Ocean), while three (childhood, healthy lives and ageing well) are greatly influenced by the health of the ecosystem, and one (science for technological innovation) is intently focused on ensuring we have the capability to turn this knowledge into vigorous new areas of sustainable economic activity.

Arguably, we are more dependent on our natural environment for earning our living and maintaining our lifestyle than any other developed country.

Meanwhile across Aotearoa New Zealand, there is growing awareness of the damage we’re doing to the ecosystem, the grave danger of ignoring that, and the abundant opportunities for responding in ways beneficial to it and us. This is increasingly matched by actions, both in campaigns for change and the development of ways to work more sustainably.

Examples of the former include Generation Zero’s push for a Zero Carbon Act, and the work of 350.org.nz, WWF, Greenpeace and other advocacy groups. Examples of the latter include the work of the Sustainable Business Network on helping small companies devise regenerative business models, and the Sustainable Business Council on getting major corporates to pledge to bigger (but not yet sufficient) commitments to reduce their carbon emissions. In addition, some major corporates are showing strong leadership, such as the commitment to carbon-neutral farming by 2025 by Landcorp, our largest corporate farmer and a State Owned Enterprise, as well as commitments from Air New Zealand and Z Energy in transport, and Vector and Mercury in electricity.

Much more is happening, too, at the flax-roots. To cite just two examples: Envirohub, the Bay of Plenty environment centre, has been running its annual Sustainable Backyards programme since 2006. The 2018 version offered more than 140 events in March, tying in over the month with annual one-day world celebrations of wildlife, forests, water and Earth Hour, when people host events, turn off their lights for an hour, and clamour for climate change action.

And Ngāi Tūhoe have built the first Living Building in the country. Its Te Kura Whare in Taneatua meets the very demanding international design and performance standards for being self-sufficient for electricity and water. Rightly, this beautiful building looks nothing like Living Buildings elsewhere in the world. It is very much a Tūhoe expression of who they are as a people, and of their home in the life of the ecosystem of Te Urewera. Even more significant was Tūhoe’s insistence in negotiations with the government on the granting of legal personhood for the Urewera National Park as the basis of a new structure and relationship for taking care of it. Building on these and other initiatives, Tūhoe are working on twenty-first-century expressions of iwi life in their communities and economic activity within ‘the living system of nature’, in their words.

These are just a few glimpses of the significant changes under way in many aspects of our lives and economic activity across Aotearoa New Zealand. Over the next few years and decades, ‘the shift from the old economy to a new, low-emissions economy will be profound and widespread, transforming land use, the energy system, production methods and technology, regulatory frameworks and institutions, and business and political culture’. This insight came not from an idealistic futurist but from the New Zealand Productivity Commission in its August 2017 Issues Paper on a low-emissions economy. The National-led Government had tasked the commission to identify economic pathways to that vital goal just months before it lost power. It was arguably the most practical of the very few steps on climate change taken by a government that had largely neglected climate change during its nine years in power. Worse, and irresponsibly, it had pushed a range of policies in agriculture, energy, transport and the built environment that had aggravated climate change.

The Productivity Commission’s final report was due out in late June 2018, after the deadline for this essay. It was certain to be a detailed, insightful, practical and encouraging document, judging by the commission’s work to date and the range of engaged, positive and ambitious submissions from organisations and individuals in business, local government, science, academia, health and civil society generally.

Below are some of the ways in which key sectors of the economy can use this transition to low emissions to greatly improve their contributions to the environmental, economic and societal well-being of Aotearoa. Please note that these are my suggestions which, in some respects, go beyond the recommendations of the Productivity Commission.

Looking first at agriculture: three virtually pollution-free, new food technologies pose the greatest competitive threat to our conventional agriculture worldwide. The first, cellular agriculture in pharmaceutical-grade facilities, grows meat from stems cells and produces synthetic versions of milk. The second, contained agriculture, grows conventional plants indoors in LED-lit, airponic-fed systems. The third uses plant materials to produce close approximations of meat. All three technologies are developing fast, thanks to their attraction to high-tech venture capitalists in Silicon Valley and elsewhere. The first is only a few years away from limited commercial sale, the other two are already available in small quantities, mainly in the United States.

There’s no way to judge yet whether consumers will treat these alternative proteins as niche or mass products. Either way, though, they will put pressure on conventional farming to reduce its adverse environmental impact. Governments, too, will be pushing for big changes in farming practices, because they are large contributors globally to greenhouse gas emissions, land and ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss.

Similarly, it’s only possible now to indicate broadly how our farmers and food companies should respond. The dairy and red-meat sectors will have to massively ramp up their research and development to reduce their animals’ greenhouse gases, which account for almost half the country’s entire emissions; most farmers will have to shift from, say, a dairy monoculture to diversified land use, such as adding some crops and forestry, or work with their neighbours to achieve the same end across their farms.

Such deep innovation must be spurred by including agriculture in the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), and by new legislated mechanisms we will likely see soon from the Labour-led Government to drive our transition to net zero emissions by 2050. Farmers also need funding for big new areas of research: for example, for measuring, managing and certifying farming practices that increase the carbon sequestered in soil. Then farmers can be rewarded in the ETS for capturing carbon this way, which improves their soil health, plant productivity, farm emissions profiles, and farm economics.

In these broad ways, agriculture will make big cuts in its emissions, thereby helping us meet our international climate commitments, according to analysis by London-based Vivid Economics. They did this research first for GLOBE-NZ, an all-party group of backbench MPs, and later for the Productivity Commission. In the process, farming should become more profitable, resilient and sustainable.

Forestry will play a major role, too, thanks to trees sequestering carbon. But the sector has to rise to four big challenges. First, planting many more natives in permanent forests, and many more natives and other species in harvestable forests, and drastically fewer radiata pine, which is an inferior timber in terms of its structural and rot-resistance qualities. Second, producing far more engineered and structural building materials from wood to help displace carbon-intensive steel and cement. Third, help develop international systems for measuring and certifying such carbon sequestration, so forest owners can benefit in the ETS. Fourth, making a big push to use biomass for industrial heat and for converting into liquid fuels, thereby displacing fossil fuels.

Such strategies would enable us to achieve the immensely difficult task of reducing our emissions from the rural side of our economy to net carbon zero (allowing for some sequestration), or even carbon negative (sequestering more than we produce).

But the other half of our emissions, those mainly from the urban economy, are almost as difficult to reduce. Here are some of the best strategies:

Energy: Move fast to convert our electricity distribution to a smart grid incorporating greater two-way electricity flows, thanks to local renewable generation from photovoltaic panels, small-scale wind and hydro, energy trading and battery storage. We would then benefit more quickly from changing technology and economics, particularly for the increasing substitution of electricity for oil and diesel in transport and for coal in some industrial processes, while also increasing the resilience of the grid.

Urban design: The carbon footprint of our cities is large. Auckland’s, for example, is 7 tonnes per person per year, and the council’s goal is to cut it to 3 tonnes by 2040. But Copenhagen, for example, is already at 2.5 tonnes, and plans to be carbon neutral by 2025. So we need significantly better urban design and transport systems, far higher energy-efficiency standards, and building codes for all new and existing commercial, industrial and residential buildings.

Above all, to make our towns and cities memorable and attractive in an increasingly homogenised world, we need to create a uniquely Kiwi expression of urbanism, one that reflects the rebuilding of our relationship in town and country with our unique ecosystems and landscapes.

Carbon-neutral tourism: It takes the burning of large quantities of fossil fuel to get our millions of tourists here, and home afterwards. Biofuels and electric and hybrid planes will solve the problem in coming decades; until then, we should devise first a voluntary scheme and later a compulsory one whereby visitors offset all of their travel emissions by buying carbon credits in native bush restoration projects here. The sums are surprisingly modest. For example, a British visitor flying economy class and enjoying a long camper-van trip around the country, perhaps visiting ‘their’ regeneration project on the way, would need to spend some $200 on some 8 tonnes of carbon credits, at current prices.

In these and all other areas of our economy, our intent focus on making sure everything we do works with nature, not against it, will be made possible by exponential progress in science and technologies – the so-called fourth industrial revolution, defined by advances in artificial intelligence, big data, robotics, novel materials, biotechnology and nanotechnology.8

We cannot take for granted our urgently needed transformation. It requires us to achieve an unprecedented speed of change, scale of change and complexity of change we have never come within cooee of before. To do so, we have to be a confident, ambitious, learning and inclusive nation so everyone can contribute to and benefit from becoming deeply sustainable. Above all, three attributes are essential to us as a nation: a common sense of what we need to do, a common purpose as to how we will do it, and common wealth from sharing the rewards widely.

For the journey, Allen Curnow offers us hope and courage in a poem he wrote in 1942, an earlier time of great crisis and conflict in the world. Commemorating the tercentenary of Abel Tasman’s brief but bloody encounter with Aotearoa, he begins by stating how simple it was then to find new lands: ‘Simply by sailing in a new direction You could enlarge the world.’ But it is his last four stanzas that speak to our nation and world today:

But now there are no more islands to be found

And the eye scans risky horizons of its own

In unsettled weather, and murmurs of the drowned

Haunt their familiar beaches —

Who navigates us toward what unknown

But not improbable provinces? Who reaches

A future down for us from the high shelf

Of spiritual daring? Not those speeches

Pinning on the Past like a decoration

For merit that congratulates itself,

O not the self-important celebration

Or most painstaking history, can release

The current of a discoverer’s elation

And silence the voices saying,

‘Here is the world’s end where wonders cease.’

Only by a more faithful memory, laying

On him the half-light of a diffident glory,

The Sailor lives, and stands beside us, paying

Out into our time’s wave

The stain of blood that writes an island story.9

1 W. Steffen, A. Sanderson, P. D. Tyson, et al. (2004). Global Change and the Earth System: A planet under pressure. The IGBP Book Series. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 131.

2 W. Steffen, W. Broadgate, L. Deutsch, et al. (2015). The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The great acceleration. Anthropocene Review, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 81–98. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2053019614564785?journalCode=anra.

3 Francesco Tubiello, Mirella Salvatore, Alessandro F. Ferrara, et al. (2015). The Contribution of Agriculture, Forestry and other Land Use Activities to Global Warming, 1990–2012. Global Change Biology, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 2655–2660. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12865/abstract.

4 Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2017). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: New Zealand 2017. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268203-en.

5 Klaus Schwab and Børge Brende (2018). Preface, in the Global Risks Report 2018. Retrieved from http://reports.weforum.org/global-risks-2018/preface-2/.

6 Kate Raworth (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Cornerstone, p. 384.

7 Roy Scranton (2015). Learning to Die in the Anthropocene. San Francisco: City Lights Books, p. 23.

8 The fourth industrial revolution is encapsulated in recent progress in artificial intelligence (AI), biotechnology, nanotechnology, 3D printing, etc. It follows the first (of 250 years ago), the second (roughly 1870–1914, based around steel, oil and electricity), and third (the Digital Revolution, ongoing since the 1980s).

9 Allen Curnow (2017). ‘Landfall in Unknown Seas’, in Elizabeth Caffin and Terry Sturm (eds), Allen Curnow: Collected Poems. Auckland: Auckland University Press. Copyright Tim Curnow; reproduced with permission.