2

CAN WE SOLVE THE HOUSING CRISIS?

Leonie Freeman

All Kiwis want is someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work, and something to hope for.

— Norman Kirk

‘NEW ZEALANDERS RANK HOUSING AS THE MOST important issue facing New Zealand.’ This was the lead in the Roy Morgan Research report of February 2017, in which a massive 41 per cent of respondents in the latest poll mentioned government / public policy / housing as their main concern. Housing affordability / increasing house prices and housing shortage / homelessness were the main issues identified, at 15 and 11 per cent, respectively.1 It’s a rare day when housing does not feature prominently in the media.

Much of the focus has been on Auckland’s worsening housing crisis — which is not surprising, as it’s something of a horror story. According to a 2017 Demographia survey, Auckland is the fourth most unaffordable city in the world in which to buy a house.2 And what’s worse, we are barely building enough houses to meet the city’s needs. The Auckland Unitary Plan, ratified in August 2016, states that the city needs 14,000 new houses each year for the next 30 years. In the 12 months to June 2017, we completed 6827 — not even half the required number.

And our housing challenge extends much further. Queenstown is now more expensive to live in than Auckland: wages are lower there, while houses are about the same price, squeezing would-be buyers. The median house price there is now 11.72 times the median annual household income, whereas Auckland is at 9.21. The Demographia survey rates a multiple of 3 or under as affordable. Severely unaffordable is 5 and over. Using this baseline, Wellington, Tauranga and Christchurch are also classified as severely unaffordable.

Housing really matters

Housing is one of the most important staples of our lives. Of course, we have a basic need for shelter, but it goes deeper. It is fundamental to our well-being, our security and stability, our health, as the base from which we raise our families and shape our experience of the world. Housing is at the heart of our communities, too. If we want our communities, our towns and our cities to thrive, grow, remain cohesive, we need to appropriately house all the folk who make a community, including our young, key workers, families and retirees.

Housing is, however, a complex issue. A lot of positions are struck, often stridently, because we are in a ‘housing crisis’ and the debate is understandably a fevered one: It’s the demand side. No, it’s about supply. It’s property prices. No, it’s ownership rates that are falling. Immigration’s at the root of the crisis. No, it’s the investors. It’s the banks. It’s the planning limits placed on city growth … and so on.

Complex problems are not typically susceptible to simple solutions. And New Zealand’s housing issues are neither new nor simple. They can’t be determinatively pinned to one policy, one political party or one council. And let’s remember we have encountered similar headlines often during past decades. They are not even unique to New Zealand cities — many fast-growing cities around the world face a similar set of problems.

As a guide to understanding the shape of our housing policy problem, the housing continuum (Figure 1) was adapted for the New Zealand context by the community housing sector and published by Community Housing Aotearoa in Our Place.3 It illustrates (from left to right) the pathway from homelessness and emergency shelters, through assisted rental or assisted ownership, to private renting and ownership options in the market. This concept provides a way to understand the state of each housing segment, how each is performing (or failing to perform), and how each part of the continuum affects the others.

Figure 1: The housing continuum. Source: Community Housing Aotearoa

In simple terms, our task is to have New Zealanders moving from left to right along the housing continuum towards increasing independence, rather than the other way.

Measuring the crisis

Before we can address the problem, we need to understand where we are with it. Here are a few of the key components.

Housing supply

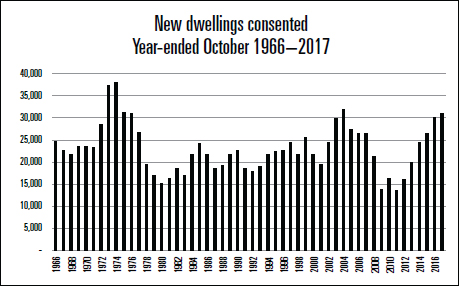

In the year ending October 2017, Statistics New Zealand reported that 30,866 new homes were consented across the country; of these, just over one-third (10,469) were in Auckland.4 This is near levels last seen in 2004, but is still well below the all-time peak seen in 1974. These new homes include stand-alone houses, apartments, townhouses and retirement village units, but exclude non-residential dwellings such as prisons, hospitals and hostels. Of the total consented, 69 per cent (21,194) were for stand-alone homes and 10 per cent (3001) were for apartments.

Figure 2: New dwellings consented, 1966–2017. Source: Statistics New Zealand

Houses completed

Just because a home is consented, it doesn’t mean it will actually be built. So how many homes have actually been completed? Here we run into a problem: there is currently no New Zealand-wide measure for completed houses. Statistics New Zealand is in the early stages of trialling some predictive modelling and Auckland Council has started to release statistics of houses completed measured against codes of compliance issued (which gives us the forementioned figure of 6827 houses completed in the year to June 2017).

Housing demand

Demand is influenced by a multitude of factors, including increasing population, the cost of borrowing, exchange rates and house prices. It is difficult to quantify, but a study undertaken by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) in 2017 indicates Auckland’s accumulated housing shortage in 2017 to be as many as 45,000 dwellings.5

Affordable housing

Clearly there’s a shortfall of housing, but it is not being measured in a consistent fashion. In the usual definition of affordable housing, one-third of household income goes towards rent or mortgage.6 One positive policy initiative can be seen in Auckland, where an affordable housing component was scripted into the Special Housing Areas (SHAs) in 2013 as part of the Auckland Housing Accord. The Auckland SHAs were established as an interim measure while the Unitary Plan was under development. There was a target set of 39,000 houses to be consented under the Auckland Housing Accord, with a requirement for about 10 per cent to be affordable. Once this legislation was passed, however, it bumped into a roadblock: there was no coordination between government and council as to either how it would be implemented or how we would know whether it was on track. Predictably, perhaps, in October 2017 a report to the council showed only 3157 houses had been completed in the SHAs during the previous three and a half years, of which just 580 were classified as affordable. Of those, 482 were retained as affordable — most of them destined to be social housing — and 98 made available to the wider public.7

House prices

The Real Estate Institute of New Zealand (REINZ) reported the median house price across New Zealand in December 2017 to be $552,000.8 This showed an increase of 6.2 per cent from the previous year ($520,000 in December 2016). From 1992 to 2017, New Zealand house prices increased at a compounded 6.5 per cent per annum.9 This rate of increase has well outstripped Consumer Price Index (CPI) and wage/income growth levels.

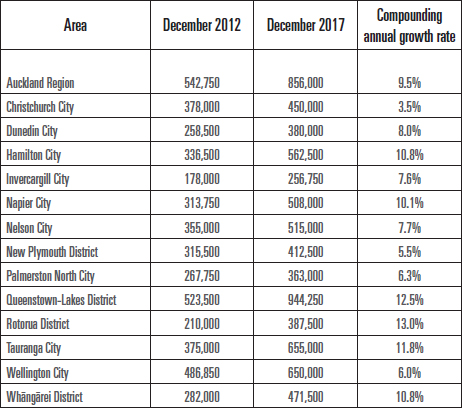

Looking regionally, we can see some extremities among the statistics, as shown in Figure 3. For example, Auckland’s median price in December 2017 sat at $856,000, showing 9.5 per cent per annum compounding growth over the foregoing five-year period. Queenstown Lakes District outstripped Auckland in its growth, showing 12.5 per cent compounding growth in the five-year period and a 2017 median price of $944,250.

Figure 3: Median price at December 2012 and December 2017, and compounding annual growth rates.

Source: REINZ New Zealand House Price Index Report, 18 January 2018

Home ownership and rental levels

In 1991 almost three-quarters (73.8 per cent) of total households lived in a home that they owned.10 In 2017 Statistics New Zealand reported that this has dropped to 63.2 per cent, the lowest rate since 1951. Of the 1.8 million homes in this country, 1.2 million were owner-occupied in December 2016 and 604,900 were rented.

Social housing

There are currently 66,187 social houses. Of these, 4874 are provided by community housing providers, and 61,313 are provided by Housing New Zealand.11 Demand for social housing has been increasing. In the September 2017 Housing Quarterly Report produced by the Ministry of Social Development there were 7327 extant applications for social housing. This was up 554 from the previous quarter. Two-thirds (4908) were classified as Priority A (determined as ‘at risk’) and one-third (2419) as Priority B (‘in serious housing need’).

Homelessness

Much about the level of homelessness depends on your definition, but all indications are that it is growing. An Otago University study released in 2016 found that the ‘severely housing deprived’ or homeless population in New Zealand was around 41,200.12 This definition includes people sleeping rough, living in cars or garages, or living in emergency or temporary shelters. This figure has grown over the past three census periods. The number of people ‘without habitable accommodation’ is lower, at around 4200. Auckland Council in 2017 released statistics suggesting there are around 24,000 homeless in Auckland alone.

SO IF WE DON’T RESOLVE THE HOUSING CRISIS, the future for our cities, and our country as a whole, looks bleak. It’s a future of rampant house prices, people living in cars and garages, more congestion, housing supply at a trickle, and many of our people — our young in particular — losing all hope of owning a home. And if this bleak future sounds familiar, that’s because it has already arrived.

What makes our housing crisis so complex and so intractably difficult to solve? To begin to answer this, we need to remember that the development of housing is a long-term venture that is not easily reversible and, generally, has an economic life of at least 50 years. Small developments can take a couple of years, while large-scale housing developments may take at least 10 years from start to finish. Accordingly, long-term decisions and long-term commitments are required. This means we have to ensure that all of the parties, from policy-makers to infrastructure providers, including developers, construction companies, key consultants and planners, are aligned in a common direction with common objectives.

At present, however, no framework exists that enables or encourages this to occur. And when you overlay the long-term conditions of development over the short-term nature of local and central government, it’s difficult to achieve the consistency, commitment and direction required for everyone to ‘scale up’ (i.e. build bigger developments to house more people) and commit to the levels required.

There is plenty of talk about getting the public and private sectors working well together so we can gain some traction. But talk is cheap — and although point-scoring is a well-understood aspect of the political process, unfortunately it doesn’t get houses built!

Looking back

Human Rights Commissioner David Rutherford was quoted recently at the August 2017 Auckland Housing Summit. He said:

Since 1948, New Zealand governments have promised internationally over and over again to deliver adequate houses to all New Zealanders. The latest was in 2015 when the government supported the United Nations Global Agenda, which included Target 11.1. This was ‘by 2030, to ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing’. Despite that, no side has yet delivered adequate housing to all New Zealanders. And here we all sit today, still facing what feels like an insurmountable challenge. The reality is that it will likely take longer than any single New Zealand government’s term in power to deliver adequate housing for all New Zealanders. Our housing issues last much longer than any parliamentary term.13

Seventy years ago, we as a country made a commitment to properly house our citizens. Seventy years on, we have still not managed it.

We can look to the ‘days of old’ and see them as more idyllic, less problematic. To be sure, it was a simpler world and expectations were more modest in the days of the ‘Pavlova Paradise’, when mass house-building by the government presented many opportunities for families to own their own home. But how accurate is it to frame mid-century New Zealand as a golden age of housing?

There can be no doubt that housing was a key focus after World War II. But the end of the 1940s saw a backlash against state housing — then the proposition being touted by an increasingly unpopular Labour Government — as the mainstream form of housing tenure. National won a landslide victory in 1949. They emphasised home ownership as a pre-eminent aspiration of all New Zealanders. The Kiwi dream was defined as owning your own home, and state housing was now seen as fit for those unable to afford to house themselves.

Instead of building a large number of state houses, as the Labour Government had done, National increased the state’s investment in home ownership.14 (Later Labour continued the thrust.) They encouraged builders and land developers to take up the challenge and build more houses; introduced State Advances Corporation 3 per cent loans; provided the option for state tenants to buy their own homes; and promulgated the Group Building Scheme, which included restrictions on size of housing and guaranteed purchase of housing for builders if they built six or more houses. The state house design was used by many builders as the standard house design of the times; some prefabrication was introduced to help increase supply and, to answer concerns over urban sprawl, multi-unit and higher-density housing was also encouraged. (Note that this was also a period of huge demographic change for New Zealand. Some 225,000 immigrants came to the country, and the overall population would rise from 1.7 million in 1945 to 3.1 million in 1975.)

Seventy years ago, we as a country made a commitment to properly house our citizens. Seventy years on, we have still not managed it.

In her book Building the New Zealand Dream, historian Gael Ferguson observed: ‘The housing policies implemented over the two decades from 1949 were remarkably successful’, and the statistics back this up. The rate of home ownership went from 61.2 per cent of all households in 1951 to 69 per cent in 1966. The number of houses built each year increased. Building consents peaked in 1974, and the total number of completed units in 1975 reached 34,400 — the highest figure since the war.

Lending, too, peaked in 1961, when 52 per cent of all residential buildings completed were funded by the state. By 1972 this had declined to 28 per cent, as concerns increased over a serious imbalance in New Zealand’s terms of trade and our national budget came under significant constraint. In any case, by the mid-1960s the Holyoake Government was arguing that the housing problem was over, and it accordingly reduced direct investment in housing. Since the 1980s, despite our larger and richer population, building rates have never matched those levels. As a result there is an annual shortfall, and it is growing.

My parents: a case study

My parents, Alice and Garry Freeman, featured in these statistics. (It’s important to recognise the numbers stand for real people.)

My parents in 1962, just before they married.

They were both teachers — Mum came off a farm out in the boondocks of Gisborne, and Dad had grown up in Laingholm, Auckland; his own father had been injured in the war. There was no family money on either side, but buying a house and establishing roots was a key objective for them both.

That was their dream, and they were able to buy something because there was a massive construction programme under way, driven by the government of the time.

Scrimping and saving, they put together the £500 deposit ($21,500 in today’s dollars, adjusted by CPI).15 They got a 3 per cent loan from State Advances to buy a new house, and they borrowed the money from the insurance company to buy the land. This got them a three-bedroom house on a quarter-acre section in Konini Road, Titirangi, Auckland. It had no garage, no carport, no paths, no driveways, and no carpet, curtains or insulation. Dad told me it was two years before they put down carpet, and over time he concreted the driveway and paths himself, bit by bit.

Now I’m not advocating that this is the standard to which houses should generally be considered ready for sale — but it was actually a pretty good house and, more importantly, it was the product of a comprehensive, collective programme of action designed to sustain strong and stable communities. (The section has been subdivided since, and the house extended a number of times.)

My parents’ house in Titirangi, Auckland.

So they had a house. Mum stopped working as three kids came along. Dad took on a second job: driving taxis. Money was tight, as it was for everyone in the neighbourhood. But we were part of a community, and we felt we were all in it together. Dad taught at Titirangi Primary, and Mum — when she went back to work — was at Kelston School for the Deaf. We put down roots, went to school and had a stable foundation on which to grow. We were there until we moved to Christchurch when I was 11.

My parents’ story — and the impact for the good it had on all our lives — is one of the main reasons I have been so vocal on the importance of fixing our housing crisis. The key issue to me is this: teachers today would struggle to buy a house in many places in New Zealand. In fact a recent survey showed that 64 per cent of all new teachers had given up hope of ever owning their own home in Auckland.16 And yet, Auckland City has a fundamental and inexorable need of key workers such as teachers (as well as police, nurses, and many others).

My experience growing up in what really was a golden age (in some respects, at least) informs my conviction that we need a society where young families can aspire to be part of a community and buy a house if they choose. Equally important, I want a city and a country where renting is affordable and secure — because more and more of us are finding ourselves in the position of having to rent. It’s clear we should be doing much, much better.

Looking beyond the local

Bad as the housing situation in New Zealand is, we shouldn’t fool ourselves that we are unique (nor that we have to conjure up unique solutions). It is a universal truth that providing decent affordable housing is fundamental to the well-being of people and the smooth functioning of economies. However, being able to meet the housing need, in developing and advanced economies alike, is proving a huge challenge for many cities around the world. It may not be much of a comfort to know we have companions in misfortune, but it is a fact that we are not alone in having to confront and solve a housing crisis.

To put our experience in a wider context, let us consider three factors. First of these is the cost of housing. Housing costs — factoring in items such as mortgage/rent, gas, electricity, water, furniture or repairs — take up a large share of the household budget and represent the largest single expenditure for many individuals and families. New Zealand households on average spend 26 per cent of their gross adjusted disposable income on keeping a roof over their heads. This is the highest in the OECD, where the average is 21 per cent.17

A second factor is rising house prices. The International Monetary Fund analyses real house price growth in 63 countries around the world.18 In 2017 New Zealand had the fifth-highest real house price increase, at 12.4 per cent. This was behind only Hong Kong (13.9), the Philippines (14.2), Iceland (15.5) and Serbia (19.5). At the other end of the spectrum are countries where house prices have been dropping — Brazil (-16.7), Ukraine (-14.1) and Russia (-9.2).

The third factor is home ownership. Rates vary considerably around the world, but, based on the International Home Ownership comparison provided by Trading Economics, some places report home ownership rates greater than 90 per cent — among them Singapore, China and Romania. At the other end of the spectrum, with home ownership rates below 55 per cent, we see Austria, Germany, Hong Kong and Switzerland. New Zealand sits just below Australia and above the United Kingdom and United States.19

But let’s take a step back. Why are we so concerned about owning our own property in the first place? Look at economies like Germany. They feel much less compulsion to buy a property, mainly because the German government controls the rental market so that a family can securely rent a home for decades. Much of the rental stock is owned by large investment organisations with a long-term hold policy.

In New Zealand, this is not the case. The majority of rental stock in New Zealand is owned by ‘Mum and Dad’ investors, each owning fewer than five properties. We do not have the large institutional investors in the residential sector similar to those found in countries such as Germany. Current tenancy legislation tends to encourage shorter, more flexible tenancies. It is rare to see fixed-term tenancies longer than 12 months in New Zealand. Current legislation does offer the ability to sign longer-term fixed contracts, such as three or five years, but this is not common.

Much of the drive for home ownership, therefore, is driven by a quest for security and stability, as well as the need to put down roots and be part of a community. Or perhaps because so many nineteenth-century New Zealand settlers hoped to build a society free of the vagaries and oppression of their homelands, the drive to ownership far surpasses that in parts of Europe. Then again, maybe the reason lies in an insecurity complex born out of the Great Depression, with later ‘chill’ reminders like the Global Financial Crisis propelling a belief that security of tenure entails owning our own home. Or we could dig back further to Britain, where home ownership has long been viewed as a mark of economic progress, encapsulated in the saying that ‘a man’s home is his castle’ — echoed in the National Government’s vision back in 1949 of a ‘property-owning democracy’. Whatever the motivation, it would seem that the urge for ownership is in our DNA.

Looking forward

So it’s not a black-or-white issue of everyone owns or everyone rents. It’s about choice, and about enabling people to buy a home if that is their aim. Every aspiration begins with a vision, a goal and a passion. I recall John F. Kennedy at the start of the 1960s stating in his inaugural address that America would put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. At the time, the United States didn’t have the technology or materials to do it. But the goal focused a nation.

We are at a crossroads, and we have a decision to make. We can continue with the status quo. Or we can set the audacious goal — more prosaic, perhaps, but at least as vital as a man on the moon — of fixing our country’s housing crisis.

I want to ask you to suspend your disbelief for a moment and come on a trip with me into the future of Auckland, to paint a picture of where we are heading if we keep doing what we are doing now. Imagine that the year is 2030. Most of us are using driverless cars, or the rapid transport light rail that was announced as an election sweetener late in 2017. Most of our key workers — teachers, nurses, administrators, police officers — share the train with us, but they come in from further out on the lines: Helensville, Pokeno, Whāngārei. We will still live in a beautiful city, with enviable natural resources of harbours, beaches and bush. We got that part right and learned to look after it!

Good housing is directly related to better health and education outcomes, better justice outcomes, better economic outcomes and better communities.

The population of Auckland is now over 2 million — about 40 per cent of the national population. The city has its new Convention Centre, many new high-grade hotels, a modern skyline featuring new residential apartments and office towers. We go about our business as best we can, but nonetheless something niggles away, something that is out of balance, because we believe in fair play and looking out for each other.

You could argue that we have plenty of great things to distract us from that. As the holders of the America’s Cup we have continued to develop a world-class urban environment reshaped with people-oriented streetscapes, laneways, public squares and parks. We are even gearing up to defend the Rugby World Cup men’s and women’s again next year, here in Auckland.

Mobile technology means we can do anything, anywhere, with tiny devices; many of us are wearing smart eyewear, live-streaming to connect with people in all parts of the globe. Medical advancements, robotics and artificial intelligence have meant the loss of many jobs, but have also created many other new opportunities.

The one factor that has changed little is housing. The industry has become more fragmented and there remains no overall leadership on the issue. The game-playing and finger-pointing between local and central government have continued, to the detriment of the city. In 2017, we realised we had broken the social contract we had with our people. We said to each other that if we worked hard, educated and looked after our children, paid our taxes and accommodated ourselves to New Zealand life, we could expect a safe, dry, secure, affordable house to live in. A place to call home.

We believed that was important in 2017. We knew it was important, because we knew then that housing isn’t just about shelter from the wind and rain. Good housing is directly related to better health and education outcomes, better justice outcomes, better economic outcomes and better communities. For all that, since 2017 we have continued to deliver the housing supply at the same rates. This means we have gone from a shortage of 35,000 houses in 2017 to over 130,000 in 2030. (Two Hamiltons’ worth of housing development needed to be crammed into Auckland by 2030 — so said the CEO of Auckland Transport, David Warburton, in 2017. But we didn’t listen.)

Core Logic estimates the average Auckland house price in 2030 is now nearly $3 million — an astonishing 19 times the average household income. This affordability ratio has pushed Auckland off the chart by international standards. Home ownership has continued to drop, and now fewer than half of all Aucklanders own their own home.

Ghettos unlike anything we have seen before in New Zealand have become embarrassingly common. Homelessness has escalated, and the need for social housing and other support services has increased dramatically. There are now 500,000 households in Auckland who cannot afford even the median rent. This is up from 120,000 in 2017.

The social impact has been huge. With the widening gap between the haves and the have-nots, communities have been decimated and many are in decay. On one side we see more gated enclaves and the ever-burgeoning paraphernalia of security, while on the other we see boarded-up windows and wrecked cars in front yards. Auckland is becoming more like the cities overseas we never wanted to be. People who came here to escape failing, violent cities are packing up and heading off again in search of safety.

In 2030 we have a critical shortage of key workers in Auckland — our teachers, our nurses, our police. We are even starting to see in Auckland what San Francisco experienced in 2015, where critical key workers live in mobile RVs outside their place of work. And the chances are, to reach their workplaces they have to manoeuvre around homeless people living in the doorways.

That’s a dystopian, but not at all implausible, vision of the future — just 12 years hence. It is not where I want to live. Most New Zealanders feel the same. So what to do?

Organising to innovate

If we want to solve these challenging social sector issues, then we need to see fundamentally greater support for organisations that create scalable, sustainable and systems-changing solutions and results. Innovation is a way of thinking. It is not about doing an old thing in a new way, but about creating a new way to do something new, or a new way to do something better.

However, this also creates the greatest challenge for many people, because so many of us are wary of new processes, new approaches. We are uncomfortable with the unfamiliar — whether it is new technology, social media, disciplined planning, measuring results, holding ourselves accountable, or stepping up and showing bold leadership. Furthermore, the existing players in any sector have resources, processes, partners and business models designed to support the status quo. This makes it difficult and unappealing for them to challenge the prevailing way of doing things. Organisations, in short, are set up to support their existing business models, and because implementing a simpler, less expensive, more accessible product or service could sabotage their current offerings, it’s almost impossible for them to disrupt themselves. This is the reason why most disruptive innovations come from outside the ranks of the established players.

I believe there is a way to resolve this crisis. In my solution, which I launched in October 2016, the initial focus has been on Auckland, but it can be applied throughout New Zealand.20 My solution is based on an approach often described as ‘collective impact’. Put simply, this is a structure for solving complex and seemingly intractable large-scale social problems. It involves bringing together all the players who have a stake in the issue to work towards the same goal, agreeing on the plan to get there, and rigorously monitoring it to ensure it stays on track.

My favourite model of a successful collective-impact project is close to home (although there are plenty of international examples, too). The People’s Project in Hamilton set an ambitious goal back in 2014: to end homelessness in the central city by the end of 2016. They have achieved remarkable success. I’m convinced that, having researched a wide range of collective-impact projects around the world, this is the approach that will work in Auckland, where so many other approaches are clearly failing.

In my planned solution, a small entity — typically a not-for-profit — acts as a central place of information, vision and coordination. It ‘joins the dots’ and provides the framework for everyone to work as partners, to bring through innovations and ideas, and to sort out blockages. It creates a unified vision that embraces all of the stakeholders, and maps out key activity areas and clear responsibilities. It’s also about reporting, so that everything is transparent and everyone is aware of how things are going. This enables the public to come on the journey as well.

In short, it is a new way of working together.

There are four key steps to the plan. We start with a vision, because without a clear sense of where we are going, we are rudderless. We create a structure, an organisational framework that can be used to implement the initiative. We build a housing framework: we can’t conceptualise a ‘fix’ for the housing crisis when we are overwhelmed and confused by the sheer number of parts — housing demand, market influences, the policy/regulatory environment, and so on — that make up the housing jigsaw. We need a method of making sense of this jigsaw, so that by seeing clearly where we are, we can move strategically to where we intend to be. And finally we draw up a unified action plan. It’s true that if you fail to plan, you plan to fail. The last step, therefore, is about accountability and ensuring we deliver on our promises and get things done. Accountability is shared, but there is differentiated responsibility.

If we commit to this framework, I believe some spectacular results can be achieved. They include:

- 420,000 new homes by 2045, with 125,000 by 2025 — 50 per cent of them classified as ‘affordable’;

- 3000 more social housing places by the end of 2018;

- an end to homelessness in central Auckland by 2022;

- improved tenure options for renters and tenants;

- home ownership levels across Auckland restored to 65 per cent by 2025.

The 2017 Auckland Housing Summit was the first step in getting the property sector groups together with the focus on fixing the problem. In early 2018, as I write this, we now have all of the parties — including the new government and council — at the table for the first time. It could be another false dawn. We’ve had plenty of those! But I am hopeful that it represents a fresh drive to solve our housing crisis. The clock is ticking.

Nothing could be more important if we are to avoid turning Auckland into a Tale of Two Cities and New Zealand into a Tale of Two Countries. Inequality is today’s hot-button issue. It was also yesterday’s. The nineteenth-century British prime minister and novelist Benjamin Disraeli pointed eloquently to the growing discrepancy between rich and the poor in an observation that resonates to this day:

Two nations between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts, and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets … The rich and the poor.21

For the sake of all New Zealanders, whether they are house-rich or house-poor, we must, as a minimum, commit to the goal of adequately housing the population by 2030. Nothing less will do.

1 Roy Morgan Research (2017). Most Important Problems Facing New Zealand in 2017, Finding No. 7128, 27 February. Retrieved from http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/7128-most-important-problems-facing-new-zealand-february-2017-201702271519.

2 Demographia (2017). 13th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, 23 January. Retrieved from http://demographia.com/media_rls_2017.pdf.

3 See http://www.communityhousing.org.nz/housing-continuum/.

4 Statistics New Zealand (2017). Building Consents Data — October 2017. Retrieved from www.stats.govt.nz.

5 Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (2017). Briefing for the Incoming Minister of Housing and Urban Development. Wellington, MBIE, p. 14.

6 Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved from http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/nz-social-indicators/Home/Standard%20of%20living/housing-affordability.aspx.

7 https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/97736731/section-prices-doubled-as-initiative-worked-to-boost-affordability.

8 REINZ Monthly Property Report, 18 January 2018. Retrieved from https://reinz.co.nz/public-archive-2018.

9 REINZ New Zealand House Price Index Report, 18 January 2018. Retrieved from https://reinz.co.nz/public-archive-2018.

10 http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=11779664.

11 September 2017 Housing Quarterly Report — Ministry of Social Development.

12 Kate Amore, Severe housing deprivation in Aotearoa/New Zealand 2001–2013, He Kainga Oranga / Housing & Health Research Programme Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11908336.

13 Leonie Freeman, Robyn Phipps, Anna Crosbie, Paul Gilberd, Kitty Rothschild, Collecting Minds, Collective Action: A report on the findings from the Auckland Housing Summit, 1 August 2017. Retrieved from www.aucklandhousingsummit.co.nz/report.

14 Gael Ferguson (1994), Building the New Zealand Dream. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

15 Reserve Bank Inflation Calculator. Retrieved from https://rbnz.govt.nz/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator.

16 http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11894085.

17 OECD Better Life Index (2017). Retrieved from http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/housing/.

18 International Monetary Fund, Global Housing Watch. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/external/research/housing/.

19 Trading Economics Home Ownership Rate. Retrieved from https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/home-ownership-rate.

20 The details of this solution can be found on my website, www.thehomepage.co.nz.

21 From Disraeli’s 1845 social-commentary novel Sybil, or The Two Nations.