5

IS NEW ZEALAND THE BEST PLACE IN THE WORLD TO BE A CHILD?

Andrew Becroft

Introduction

IN JANUARY 2018, THE PRIME MINISTER, the Right Honourable Jacinda Ardern, expressed her government’s profound ambition for Aotearoa New Zealand to be the best place in the world to be a child.

I believe that many New Zealanders of my generation grew up convinced that this was already the case. It drew many of us, after stretching our wings for the big OE, to return home to have our own children. Sadly, New Zealand can no longer claim to be a place where all children and young people and their families flourish. Part of my motivation for taking up the role of Children’s Commissioner was to help redress the imbalance.

In this chapter I explore three big issues for New Zealand’s children and young people (those aged under 18). I look at what we can do to reclaim international pride of place in our treatment of and provision for our tamariki. First, however, where might we have gone wrong? And what do we know about our children and the value of childhood now?

The end of the golden weather?

I am a fortunate baby boomer. My friends and I grew up during the 1960s and early 1970s in a settled, prosperous, middle-class neighbourhood, at a time when most communities were homogeneous and much more closely knit. There were few extremes of wealth or hardship. Indeed, and with apologies to Tolstoy, although each unhappy childhood is unique, happy childhoods all look fairly similar.1

On reflection, I realise the privilege I experienced. The truth is that a warm home, food on the table, a caring and loving family, an enjoyable education, and positive community connections and involvement should be normal for all children and families, but some communities have experienced, and continue to experience, real disadvantage. The monocultural tone and structures of state institutions has often placed barriers to access or progress for anyone who does not fit the dominant mind-set. Communities particularly affected have been tangata whenua (both urban and rural) and Pacific peoples.

Fifty years ago, we basked in the somewhat deluded self-image of being clean, green and socially progressive, a land where everyone gets a fair go.

‘We are better than this’, cartoon by Rod Emmerson. Source: The New Zealand Herald, 17 June 2017. NZH-1092507/newspix.nzherald.co.nz.

Although it may once have been so for many of us, I hope it is clear to New Zealanders that it is no longer the case. There has been growing stratification. We must realise that our colonising heritage has sowed the seeds of intergenerational disadvantage for tangata whenua that we are still struggling to redress today. As a result, too many Māori families today struggle with low incomes, increasingly precarious employment, and enormous disadvantage resulting from pressures on housing, wages and education.

The litany of negative statistics for which New Zealand leads (or nearly leads) the world needs no rehearsal, and includes youth suicide, bullying, abuse and neglect. They must be regarded as our ongoing national shame. In bald terms, 70 per cent of children and young people are doing well, and some are doing outstandingly well. But 20 per cent are struggling, and 10 per cent do as badly as — if not worse than — children living in the most disadvantage in comparable OECD countries. How did it reach this point? And why do tamariki and rangatahi Māori disproportionately bear the burden?

Who are New Zealand’s children and young people?

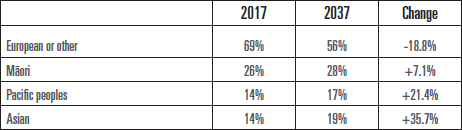

There are 1.1 million children and young people under 18 years old in New Zealand: that’s almost one in four of us (23 per cent). We want the best for all of those children and young people. But lifting child well-being is a significant challenge, and is one which is made particularly difficult for two reasons. First, children, while growing in numbers, will constitute a declining percentage of the overall population, given the growth in the number of senior citizens. The taxpayer dollar will be increasingly stretched to meet the understandable needs of an ageing population. Second, by 2037, Pākehā/European children will only just make up the ethnic majority — and there will be relatively greater growth in the ethnicities that are already disproportionately represented in the most disadvantaged cohorts.

Table 1: Children’s identified ethnicity (0–18 years). Estimated ethnic breakdown of current (2017) and projected New Zealand population (to 2038) based on 2013 census. Source: Statistics New Zealand, August 2017. Notes: (1) Some children identify with more than one ethnicity. (2) Numbers do not total 100% as some children identify with more than one ethnicity.

To prepare for the future, we must acknowledge our past

Some of the current inequalities date back to the British arrival in New Zealand, the alienation of Māori from their land, and attempts to legislate away Māori language and culture. Land and other resources, Māori self-determination and Indigenous identity were eroded in this process. This is an unpalatable but unavoidable truth for all New Zealanders. We have struggled to acknowledge these uncomfortable parts of our history, and to continue to do so is to fail our children.

The effects of some of these inequalities were mitigated by the safety net of income, housing, education and employment support provided by the state from the 1930s onwards. Social initiatives such as milk in schools, free university education and social housing all gave us a sense of being part of a country where everyone was looked after.

The share-market crash in 1987 and the so-called Mother of all Budgets in 1991, which dealt a major blow to benefit levels, marked the start of a rapid and significant growth in child inequality and disadvantage.2 The economic reforms begun in the 1980s had also opened the door to an individualistic view of achievement in which a person’s value to society was measured by their economic productivity. Less value was placed on child-rearing, voluntary work, or any of the other roles in society that contributed to cohesive communities where we looked out for each other.

As former prime minister Sir Jim Bolger said in an interview with Guyon Espiner in April 2017:

Do I believe that the gap between those who have and those who have not at the moment is too big? Yes …. [Neo-liberal policies] have failed to produce economic growth, and what growth there has been has gone to the few at the top … There has never been such a concentration of wealth in the top 1 per cent, in fact half of 1 per cent, than there is in the world today. So, demonstrably, that model needs to change.3

The significant systemic failure resulting from the rapidly changing and heavily restructured New Zealand since the 1980s has exacerbated the over-representation of tangata whenua and Pacific peoples in hardship statistics. Many have overlooked this systemic cause of hardship, and have instead blamed it on poor individual choices and irresponsible parenting. Lack of understanding of this system failure encourages ongoing ignorance, blame, and an absence of empathy: ‘If they would only work harder, pull themselves up, make better decisions, and stop complaining, they (and their families and children) could overcome their economic and social deprivation.’ This attitude has to change.

I see this, for example, in some of the rhetoric around youth justice. Young offenders are often characterised as hooligans, thugs, or disrespectful and irresponsible rule-breakers. Indeed, most young people break the law (even in small ways) at some stage while growing up and as their frontal lobe develops, and it is right that they be held to account and encouraged to accept responsibility for their offending. But for serious and persistent young offenders, it is more often the case that they are a symptom and product of a disadvantaged, dislocated and damaging environment.4 They have been victimised before they create victims: abused before they abuse. Family, education, their communities and state intervention have all failed them. And in many cases, the families themselves have been failed.

Over the past three decades, our youth justice system has tried to steer young people away from greater involvement in crime and offered more constructive, community-based solutions — not so much diversion from crime as diversion to a better path. There is recognition that young people, once in the system, too often see themselves as criminals. The system itself too readily views them as participants in the so-called ‘justice pipeline’. This labelling, regrettably, has a high risk of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy,5and the pipeline metaphor implies bleak prospects for breaking out of an apparently inevitable trajectory of adverse life outcomes. In the words of a New Zealand professor of psychology based in the United States, Terrie Moffitt, ‘The professional nomenclature may change, but the faces remain the same as they drift through successive systems aimed at curbing their deviance: schools, juvenile-justice programs, psychiatric-treatment centers, and prisons.’6

The architecture and core principles of the New Zealand youth justice approach are sound, and are recognised internationally as world-leading. However, we need to shift our thinking in order to make real progress in addressing the underlying causes of crime, particularly structural poverty, high rates of childhood abuse and neglect, intergenerational disadvantage and trauma, educational failure, lack of employment opportunities, broader socio-economic disadvantage, and unidentified neuro-developmental disorders.

If people deny child poverty and relative disadvantage in this country, it is perhaps because, in their minds, New Zealand is still the idyllic place of their childhood. However, if we want our children and young people to live in healthy families and enjoy the opportunities of past generations, we need to recognise the reality of New Zealand in 2018, following decades of underinvestment in the environment, towns, regions, and in families and children. We stand in stark contrast to a country like Sweden, which prioritises and focuses on children in legislation and policies in a way that New Zealand easily could, but does not. Our Parliament does not use child impact statements prior to passing legislation; families and child support are less prioritised; and those in child-caring roles are less valued and assisted.

If people deny child poverty and relative disadvantage in this country, it is perhaps because, in their minds, New Zealand is still the idyllic place of their childhood.

We need to shift what we value in our society. We need to move from individual to collective action, from a purely economic view of well-being to a holistic one, and to valuing children, not just for their future potential, but for the taonga they are. Many children and young people have individual agency and the capacity to contribute now. All of these shifts would have tangible implications for their lives. Rhodes scholar, law graduate and author Max Harris has suggested that our public discourse and policy-making needs to put a greater focus on the values of care, community and creativity,7 and has outlined some real steps to achieve that. His is a clarion call on behalf of a new generation.

We need to strengthen the institutions that prioritise the collective good, such as community centres, churches, libraries, trade unions and sports clubs. We also need to promote those values in other institutions, including local government, business and Parliament.

It is exciting to recognise that some of the solutions will come from children and young people themselves. For example, in 2015 Waimarama Anderson and Leah Bell petitioned for national commemoration of the New Zealand Land Wars, and we now have an annual day to mark this. This highlights the need for us as adults to spend time listening to young people.

The importance of being … a child

At the Office of the Children’s Commissioner, we are committed to making New Zealand a place where all children and young people thrive. It is easy, yet too simplistic, to see children and young people as potential adults, and to consider childhood important only in laying the foundations for a contributing adulthood. But we believe that they have the inherent right to a happy childhood because they have value now, in their own right, irrespective of their future benefit to society.

While it is crucial to keep children safe and secure, and provide them with good healthcare and education, childhood should also be a time of innocent joy and fun experienced through activities, friends and play. Let children be children, for as long as possible. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (the Children’s Convention) of 1990 protects these as the inherent right of all children and young people. Stating them in the convention is important, because children and young people don’t have the same ability to influence society and the decisions made about them, and few of these rights are protected anywhere else.

Challenges for children and young people

This lack of influence is a main reason why we have a Children’s Commissioner in New Zealand: as a champion, an advocate and a watchdog for children. In particular, we want to help address some specific challenges that face children and young people. Three issues above all are pressing: child poverty, supporting tamariki Māori, and children’s rights.

1. Child poverty

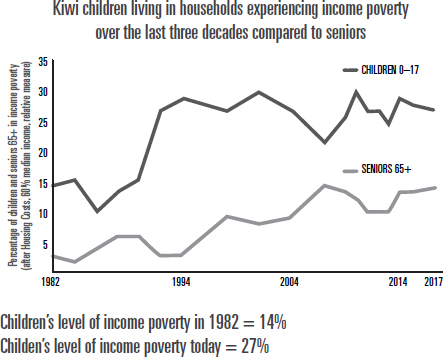

Child poverty is a relatively recent, yet fundamental and far-reaching issue in New Zealand. As Figure 1 shows, the biggest increase has been since the late 1980s. The latest data shows that 27 per cent (290,000) of all children and young people live in households earning less than 60 per cent of the median income, and 6 per cent (70,000) lack nine or more internationally agreed essential items for everyday life from a list of 17 such items. These include regular meals with meat or other protein, shoes in good condition, warm, dry housing, and the family’s ability to regularly pay essential bills. What is not shown in the graph is that Māori and Pacific children disproportionately carry the burden, with rates twice that of Pākehā children.

The impact of poverty is not just the stress of enduring financial and material hardship. There are many flow-on effects, such as children having fewer outings with parents or family holidays, and being unable to participate in activities like sports or music. This lack of opportunity can reduce childhood to a place of narrow horizons and limited enjoyment, and decreases the potential for these children to thrive in education and in their communities. In 2012, the Children’s Commissioner’s Expert Advisory Group on Solutions to Child Poverty observed:

These differential outcomes, as well as the neurological responses to growing up in poverty, mean that childhood poverty can leave life-time scars, with reduced employment prospects, lower earnings, poorer health, and higher rates of criminal offending in adulthood. It need not be this way; nor should such outcomes be tolerated.8

In my time as Children’s Commissioner, it has become apparent that all roads lead back to child poverty and material disadvantage. Poverty alone does not cause adverse life outcomes, because many poor families do well against the odds, but it is inextricably associated with them. Living in a household under such circumstances can take a toll, and it is well documented that the stress of poverty can lead to bad decisions, such as taking on problem debt, drinking, or taking drugs to alleviate uncertainty, stress and shame.

Child Poverty Trends Over Time

Income-related child poverty rates are much higher now than in the 1980s

Figure 1: Percentages of children and seniors experiencing income poverty 1982–2017 (After Housing Costs, 60% median income, relative measure). Source: Child Poverty Monitor 2017. The Child Poverty Monitor is a partnership project between the Children’s Commissioner, the JR McKenzie Trust and Otago University. www.childpoverty.co.nz.

Have we lost some of our capacity for empathy in this country? Do we lack the ability to imagine how we would react in similar poverty?

At the time of writing, proposed child poverty reduction legislation is before Parliament. Child poverty is an issue so important that the prime minister has taken it on as her own newly created portfolio. Measures and targets can help monitor progress towards this important goal. I am hopeful that we will see a significant drop in the child poverty statistics in the next few years, and certainly by 2030. This is the goal encapsulated in the first of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) signed by New Zealand, along with 192 other countries, in 2015 in New York. Yet it and all the SDGs remain largely unknown and rarely referred to within this country. As night follows day, when we see this goal achieved, we should also see a commensurate decline in all of the unacceptable statistics that mark New Zealand out as a leader in childhood adversity.

In 2012, the Expert Advisory Group made 78 comprehensive recommendations which encompass realistic solutions to poverty. While many of these recommendations have been partially addressed, in an ad hoc way, there has been no comprehensive plan to implement them.

2. Supporting tamariki Māori to thrive

Me huri kau koe i ngā whārangi o neherā; ka whakatuwhera i tētahi whārangi hōu mō ngā mea o te rā nei, mō āpōpō hoki.

You must turn over the pages of the past; you must open a new page for the things of today and tomorrow.

—Sir James Carroll

Another inescapable challenge is how best to support the 25 per cent of children and young people who identify as Māori. Many, in fact most, Māori children do well. We need to be very careful not to make negative generalisations. But too many of our tamariki Māori are represented in the 30 per cent of children and young people who experience real adversity. Our existing systems — including education, healthcare and protection, and youth justice — simply do not sufficiently support them to thrive. To rectify this situation, we must address the underpinning structures that help perpetuate it.

I do not presume to speak for Māori. What I can do is pass on the views of Māori leaders and practitioners who speak to me and to our office. The future of Māori children and young people is bound up with the future of their communities. Government’s role is to empower and resource Māori communities, whānau, hapū and iwi to determine and drive the solutions that work for them.

We have a sad legacy of state intervention, resulting in the removal of Māori children and young people from their whānau, hapū and iwi and their subsequent placement in Pākehā institutional environments. There, they lost their identity and, in far too many cases, experienced the very abuse and neglect that they were removed from their families to avoid. This stemmed from a fundamental ignorance of the place of the child in Māori society. Misplaced faith in the effectiveness of a monocultural system applying monocultural solutions to Māori children and their families enabled the state to perpetuate intergenerational harm. And in recent years many Māori children were placed with hapū or iwi, but too often without the necessary support and assistance — again leading to repeated abuse and unacceptable life outcomes.

The Royal Commission of Inquiry into Historical Abuse in State Care, established in early 2018, will comprehensively hear the stories of survivors. Among other things, the commission will suggest steps to prevent further such abuse in the future.

In 1988 the seminal report Puao-te-Ata-tu (Day break) identified that the systems for the care and protection of children and the responses to child offending were regarded as state-dominated and disempowering for Māori families, children and young people.9 In particular, it found that Indigenous Māori culture had been marginalised, with whānau, hapū and iwi effectively shut out from decision-making about their own children.

This report ultimately led to the ground-breaking, and in some senses revolutionary, Children, Young Persons and Their Families Act 1989. The legislation gave a clear signal that whānau, hapū and iwi were the best agents to improve the well-being of their tamariki. These three groups constituted the ‘powerhouse’ of Māoridom to which resources and responsibility had to be shifted. But the reality did not, and still does not, match the vision. We missed a golden opportunity for a revolution to transform the lives of Māori children and young people.

An example was the introduction of family group conferences (FGCs), to be used where children and young people were in need of care or protection, or when they had (allegedly) offended against criminal law. The purpose and the vision was that the state would stand aside, and family, whānau and, where invited, hapū, iwi and family groups would be given responsibility and power to make decisions. The vision never fully eventuated. In particular, hapū and iwi were not often meaningfully invited, involved or resourced to do so. Similarly, the system did not adequately embrace the Māori Urban Authorities movement.

Almost three decades on from the original Act, FGCs have still not reached their full potential. There are pockets of excellent practice and some outstanding examples, and FGCs are now ingrained in youth justice and care and protection. However, there is too much inconsistent practice, a lack of proper resourcing, frequently inadequate preparation, patchy training of coordinators, insufficient whānau and victim attendance at FGCs, and limited attempts to identify and invite appropriate hapū and iwi and wider family members. The original vision was not supported by practice, and the hoped-for change withered on the vine.10

In my experience, failings in the way that state institutions interact with tangata whenua and Pacific peoples are all too common. We are a long way from a utopia that is founded on the underlying bicultural relationship between Māori and the Crown and which is operating in the context of a multicultural present. If Martians landed in New Zealand tomorrow and observed that over 60 per cent of our youth justice and care and protection population was Māori, but were dealt with by a predominantly Pākehā system, they might well conclude there was no intelligent sign of life on Earth!

As Children’s Commissioner, I am committed to holding government agencies to account in their partnership obligations under te Tiriti as they deal with tamariki Māori.

Māori are not problems to be solved, we are potential to be realised.

—Rangatahi, Ngā Manu Kōrero, 2017

The changes that Puao-te-Ata-tu called for were not limited to social welfare. However, the report was certainly damning in its assessment of how tangata whenua were treated by what was concluded to be a racist system that paid no heed to cultural considerations. It called for change in housing, health, education and employment. We are struggling to see these widespread recommendations realised even now.

Puao-te-Ata-tu should be essential reading for anyone in the public sector. It was shocking enough to have the level of institutional racism exposed then. Have things improved significantly since? The report’s very first recommendation bears repeating:

To attack all forms of cultural racism in New Zealand that result in the values and lifestyle of the dominant group being regarded as superior to those of other groups, especially Māori, by:

(a) providing leadership and programmes which help develop a society in which the values of all groups are of central importance to its enhancement; and

(b) incorporating the values, cultures and beliefs of the Māori people in all policies developed for the future of New Zealand.

When addressing the well-being of tamariki Māori, much more consideration and respect need to be given to a Māori world-view and how state decisions can enhance the mana of the child. We cannot afford to wait another 30 years for this to happen.

There’s a taniwha in my river. People say it’s a log, but I know it’s a taniwha.11

The development of the new Oranga Tamariki, Ministry for Children and its enabling legislation presents a second chance for a revolution, to make a real shift towards whānau, hapū and iwi involvement and responsibility for the well-being of their tamariki. This will mean properly resourcing iwi and giving them the opportunity to build local responses for tamariki Māori who might otherwise be taken into state care. Only then will we see the heralding light of the new dawn — te totara wahinga i waenganui o te po raua ko te awatea — promised so many years ago in Puao-te-Ata-tu.

Ka pū te ruha, ka hao te rangatahi.

As the old net is laid aside, a new net is remade.

3. Children’s rights

At the time of writing, New Zealand had signed the Children’s Convention 25 years ago. It is the most signed document in history, ratified by 192 countries. It is also an exciting document that, even today, still speaks powerfully. It is a charter of guaranteed entitlements that all children and young people deserve, and which, when faithfully applied and upheld, will ensure that our children and young people flourish, prosper and thrive.

The convention is often summarised as containing four broad child rights categories:

- Protection from all forms of cruelty, abuse and neglect.

- Provision of all services and supports for life, survival and development.

- Participation in decisions that affect them, and having their voices and views heard.

- Promotion of their best interests and well-being, and ensuring all rights are upheld.

If the Children’s Convention were to be fully implemented in New Zealand, decisions and policies would always be made in the best interests of children and their well-being — irrespective of identity, appearance, gender, sexual orientation, culture, religion, language, disability or socio-economic status. All children and young people would benefit significantly, but especially those in the most disadvantaged 30 per cent.

It is worth noting that talk of child rights can cause tension and anxiety for Māori and Pacific people’s communities. This is because the immediate inference is that children should be individualised and seen as separate from their whānau, hapū and iwi or their aiga. But this is to do a disservice to the convention. Many of the convention’s articles squarely place the child within the context of the family and uphold the child’s right to family life wherever possible.

In my view, New Zealanders have little understanding of the Children’s Convention. We do not take it sufficiently seriously, and it is seldom part of policy discussion. For instance, senior government personnel have said to me: ‘Does the convention really have any relevance to New Zealand?’ Or, ‘We do pretty well for our children, don’t we? Is there anything that it can really help us with?’ And, more worryingly still, ‘Isn’t the convention mainly for less developed countries such as Somalia, Bhutan or Mongolia? Isn’t that where it is really important?’ Frankly, such views are not open to us, as a solemn signatory of such an important international instrument.

As the statutory monitor of the convention’s implementation in New Zealand, it is no overstatement to say that to date it has been largely seen here as irrelevant. Compliance is often accidental, and ‘retrofitted’ to align with policy or statutory changes which were never originally introduced to comply with the convention.

As I realised when I attended New Zealand’s fifth examination by the Committee on the Rights of the Child in September 2016, other countries take the convention much more seriously than we do. Ultimately, faithful application of the convention in New Zealand will ensure better decisions about how we treat children and young people, and the services we provide for them. For example, article 12 provides that:

States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.12

If this requirement were ingrained in government departments (and community groups), there would be a significant change in the way we make decisions: for example, in education, health and housing policy, and in the way we respond to child poverty. In short, children and young people’s voices need to be heard in our country to influence our responses. As eloquently stated by a young student in an alternative education unit, ‘I am a library: quiet but filled with knowledge — it’s dumb [that I’m not asked].’ 13

Our office urges all agencies that deal with children and young people to assess any direct or indirect impact of any decisions affecting those children and young people. Whenever there is a likely impact, there is an obligation to seek out children’s voices, listen to them, factor their views into decision-making and report back to them about any decisions made.

In the course of our work, we regularly reach out to schools and community groups throughout New Zealand to ask children and young people about issues that are important to them. We do this not only as part of my statutory role, but also because it is the right of every child to have their say. We fundamentally believe that decisions about children and young people should always be informed by their views. And it is worth observing that the quality of government policy-making and operational practice invariably improves as a result.

One radical way of ensuring that child rights are protected, children’s voices heard, and proper focus is given to their needs could be to give 16- and 17-year-olds the right to vote. Some countries have already moved in this direction, including Scotland, Austria, Brazil and Argentina. Such a fundamental change would require a national discussion. At the same time, ‘civics’ education would need to be introduced into every classroom.

All the evidence shows that voting that starts early becomes a habit for life. At the last election, the 18–29 age group had the lowest voter turnout of all age groups. We need to think of ways to change this trend and encourage children and young people to better participate in our democracy. One 15-year-old girl recently told me that in fact she should have two votes to my one. ‘I am twice as invested in the future as you grey-haired old men,’ she said. (There was obviously no problem with her eyesight!)

In short, New Zealanders need to be much more enthusiastic and positive about child rights.

Rising to the challenge

So, are we going to be the best country in the world for a child to grow up in? In my view, we are at something of a crossroads. The challenge is particularly acute for central government, local government and community agencies, both in the policy decisions they make and how policy is turned into action. It is an inescapable challenge. How we meet it will have intergenerational consequences.

Frankly, there has never been a better opportunity to rise to this challenge. New Zealand is not experiencing war or any other external crisis. We are a relatively privileged, sophisticated nation living in a time of peace and, ironically, rising national prosperity. There will never be a better time to undo the structural and systemic damage of the past. If our generation does not try to leave the world in better shape than we found it, then who will?

This challenge is far from unattainable. It begins with a change in mind-set, and a determination, in our own family lives and communities, to prioritise children. As parents, grandparents, uncles and aunties, are we making sufficient effort to invest in the lives of our children? Does at least one family meal a day take place together at the dinner table? And is that modern-day electronic heroin, the small screen, sometimes turned off? Take note: when we ask children and young people who they most want to talk to about their concerns, they tell us that it is their parents and whānau. It might be surprising, although possibly reassuring, for most local politicians to know that they are second on the list!

At the last election, the 18–29 age group had the lowest voter turnout of all age groups.

At the government end of possible responses, let us see some significant structural change and a clear shift in economic support towards children. We would then expect to see child well-being rates clearly improve within three to five years.

This is why the Child Well-being Strategy, which at the time of writing is foreshadowed in proposed legislation before Parliament, is so important. For the first time, there will be an obligation to create an overarching plan for all New Zealand children, targeting those in specified forms of need and disadvantage. I hope the strategy would also include a clear and comprehensive set of measures by which to judge child well-being improvements. This is exactly the challenge laid down by the United Nations in 2016 when it last reviewed how well New Zealand was fulfilling its commitment to the Children’s Convention.14 There have also been promising signals with the creation of Oranga Tamariki and the introduction of a specific child poverty reduction Bill.

The challenges in this chapter call for bold action. But are the suggested solutions so revolutionary? In my view, they should be considered no more than the application of first principles. Children’s commissioners don’t often talk in the language of revolution. But if our current treatment of some children is so far removed from these fundamental principles, then maybe a revolution is required. It would hardly be without precedent.

Each of us will approach this issue with our own value systems and world-views. About 2000 years ago, a man with no children of his own, but who had charismatic community influence, said: ‘Permit the children to come to me; do not hinder them.’ As many will know, those words of Jesus Christ, recorded in Matthew’s Gospel, were a revolutionary approach to a group in the community (children) who were marginalised and of low priority, even back then. Those words still challenge us today.

As Children’s Commissioner, I have a privileged opportunity to try to ensure that our children are properly valued, flourish and thrive, so that New Zealand truly is the best place in the world for a child to grow up. I feel a huge sense of responsibility. But, of course, the challenge is for all of us. I hope we can meet it.

1 ‘All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ From: Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina (1878).

2 P. Carpinter (2012). History of the Welfare State in New Zealand. Wellington: New Zealand Treasury. Retrieved 14 February 2018 from www.treasury.govt.nz/government/longterm/externalpanel/pdfs/ltfep-s2-03.pdf.

3 Radio New Zealand (2017). The Negotiator — Jim Bolger: Prime minister 1990–97. Retrieved 26 February 2018 from https://www.radionz.co.nz/programmes/the-9th-floor/story/201840999/the-negotiator-jim-bolger.

4 K. McLaren (2000). Tough is Not Enough — Getting Smart about Youth Crime. A review of research on what works to reduce offending by young people. Wellington: Ministry of Youth Affairs. Retrieved 14 February 2018 from www.youthaffairs.govt.nz/documents/resources-and-reports/publications/tough-is-not-enough-2000-nz-.pdf.

5 Alison Cleland and Khylee Quince (2014). Youth Justice in Aotearoa New Zealand: Law, policy and critique. Wellington: LexisNexis NZ.

6 T. E. Moffitt (1996). Adolescence-limited and Life-course Persistent Offending: A complementary pair of developmental theories, in Terence P. Thornberry (ed.), Advances in Criminological Theory: Developmental theories of crime and delinquency. London: Transaction Press, pp. 11–54.

7 Max Harris (2017). The New Zealand Project. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books.

8 Children’s Commissioner’s Expert Advisory Group on Solutions to Child Poverty (2012). Evidence for Action: Solutions to child poverty in New Zealand. Retrieved 14 February 2018 from www.occ.org.nz/assets/Uploads/EAG/Final-report/Final-report-Solutions-to-child-poverty-evidence-for-action.pdf.

9 Ministerial Advisory Committee on a Maori Perspective for the Department of Social Welfare (1988). Puao-te-ata-tu (Daybreak). Wellington: Department of Social Welfare. Retrieved from https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/archive/1988-puaoteatatu.pdf.

10 Office of the Children’s Commissioner (OCC) (2017a). Family Group Conferences: Still New Zealand’s gift to the world? Reflections by Judge Andrew Becroft, Children’s Commissioner; OCC (2017b). Fulfilling the Vision: Improving family group conference preparation and participation. Retrieved 26 February 2018 from http://www.occ.org.nz/publications/reports/state-of-care-2017-family-group-conferences/.

11 In the children’s book Taniwha, by Robyn Kahukiwa (Auckland: Penguin Books, 1987), the child develops a meaningful connection with his culture.

12 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Retrieved 23 March 2018 from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx.

13 Office of the Children’s Commissioner & New Zealand School Trustees Association (2018). Education Matters To Me: Key insights. Retrieved 14 February 2018 from www.occ.org.nz/publications/reports/education-matters-to-me-key-insights/.

14 United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (2016). Concluding Observations on the Fifth Periodic Report of New Zealand, CRC/C/NZL/CO/5.