13

IS THIS THE FUTURE FOR OUR CITY STREETS?

Patrick Reynolds

A GREAT SPATIAL MIXING IS UNDER WAY: the suburbs are urbanising, getting fuller and more varied, adding more opportunities to work and remain there, and, where this is most successful, developing greater local character. Our city centres are humanising — becoming more pleasant, leafier, varied, filling with residents again — as they, too, expand upwards. The separate and monotonous character of each place that developed into an extreme during the last century is being complicated and unwound.

Supporting this, vehicles everywhere are electrifying: bikes, cars, buses, trains, ferries, even airplanes. Everything will automate (ditto — well, except the bikes). Everything will be shared, certainly all those vehicles, but particularly places, and especially the streets. Walking, biking, scootering will boom. The e-bike is the transformational vehicle of the moment.

The busy peopled city street replacing the fuming traffic-jammed road is at the heart of the solutions to the great environmental, economic, and social challenges of our age. The cities, and the parts of each city, that make this change best and fastest will thrive, and those that cling to the twentieth-century driving and sprawling pattern will stall.

The journey

We look back on the condition of Victorian city streets, all coal smoke and horseshit, carts and chaos, and marvel. It was really like that? Then in the early twentieth century, right up till after the end of World War II, it was different again; these same streets we know today were filled with people in old-style hats and coats, busy with jangly electric trams and just the occasional horse and cart. But now also a few, just a few, of those new-fangled cars. That change must have felt profound; it certainly would have smelt profoundly different.

Then very quickly after the uprooting of the tram tracks that marked every city or town of scale up to the 1950s, the current pattern of vehicle traffic domination — exhaust smoke, engine noise and pedestrian danger — totally took over. All streets became roads, and all belonged to the internal combustion engine.

This should tell us that our cities, even though the present may feel so concrete and permanent, are always changing. The rhythm of this change is not constant, however: both technology and society move on in a subtle interplay, largely incrementally, sometimes more suddenly. So, flipping this exercise, looking forward: what can we see?

It’s clear that our city streets, especially our city centre streets, are about to change profoundly again. We are at the beginning of the process of reversing the last big move; cars and trucks will be but guests instead of masters in this world. Those that are admitted will be silent, non-emitting electric machines, and will be in an environment entirely dominated by people.

Auckland will lead this street-level revolution, in a very unlikely turn of events for those used to the last half-century in this city; a more car-drowned and charmless place is hard to imagine.1 Our biggest city’s sheer size and strong growth rate have flipped it into a new state through the inescapable spatial logic of urban economics: the old sleepy, overgrown provincial town is dead. And although Auckland is now anomalous with not only its own past but also every other place in the country, changes there will help speed similar shifts in our other cities, simply by showing us all that different ways are possible, and work so well.

Below I will largely discuss the urban transformation coming in Auckland because there it is so marked and so clearly under way; but this is also happening elsewhere across the nation. And, while all our cities have their own specific conditions and directions, they will not be immune to the social and technological imperatives of this century.

Form follows transport

The whole Queen Street valley will be car-free, plied only by emergency and delivery and service vehicles, the latter at set times. (Most deliveries in city centres will be by e-cargo bike.) Tens of thousands of people will arrive and depart every hour by underground electric rail, by surface light rail, by ferry at the harbour’s edge, by 100 per cent electric buses, by bikes (both powered and not), and on foot.

Especially on foot. Because this century one form of mobility that’s making a huge comeback is proximity: being there already. The Auckland city centre is the fastest-growing residential area in the nation, expanding at six times the rate of the wider city. There are now around 50,000 inner-city residents, and new apartments are rising everywhere. You can feel this presence on the pavement; space given over to vehicle traffic last century will be taken back by people in this one.

Quite soon, say by the mid-2020s, we will be able to experience this future in good chunks of the city centre. Both Victoria and Quay Street are being halved widthways to expand people space, for walking and cycling, for tree and cafe-table space. Loitering is more valuable this century than motoring. The old fume-choked and vehicle-dominated order will quickly become as foreign an idea as the thought of streets filled with horses and carts.

This is the centuries-old power of the city that got lost in the second half of last century, in the automobile-powered anti-urban sprawl era. The city is well and truly back. And the total removal of the internal combustion engine is going to transform the urban experience. It will return the human voice and the scent of the sea to dominance. Citizens will encounter new and old sounds and smells; there will be much more variety; ‘unplugged’ buskers will be effective again; food providers will advertise by their aromas again. This is the return of streets as public places, not simply as traffic funnels.

This also means there is more space for trees on every street, because as the city re-intensifies and more of the street is returned to pedestrians and bike riders, the opportunity to green the streets must be taken. We need the environmental heavy lifting that street trees perform — shade and air purification, combating the urban heat island effect — and also their glory and beauty, and the reminder of our natural selves that only a green city can provide.

Because, and in a complete inversion of thinking of the last period, one of the major drivers of urban re-intensification is the urgent need to lower the environmental burden of human living. We have to live more compactly, move around more gently, consume much less of the earth’s surface, and stop burning its buried carbon. This can be achieved only by returning to the compact city, stopping the outward spread of recent centuries, and retrofitting current suburbs with more local amenity, while decarbonising our buildings and the travel between them.2

For those living with a lovely garden in the suburbs this may seem hard to understand; isn’t that greener than living in an apartment? The problem is not at the individual level but when it scales. It is a sad fact that the environmental positives of that individually owned greenery are all undone by the massive waste that is the suburban driving commute, and by the vast, countryside-eating spread of the city that enables us all to live in such a dispersed way. One city block can house as many people as an entire small suburb, and with a much lower carbon footprint. This doesn’t mean that existing suburbs will become just like city centres, but rather that both will grow a bit more like each other; suburbs must become more mixed-use with local walkable employment and amenity, and centres must grow leafier and more appealing while getting taller and fuller. And both will be efficiently interconnected with electric rapid transit.

This transport revolution — literally another turn of the wheel, with the addition of a citywide rapid transit network and a full cycleway network to our existing and largely complete road networks — is vital not only to unclog and purify the city, but also to ensure that access to opportunity is equitably shared among all citizens. So that anyone in any part of the city has equal access to all the employment and education possibilities citywide. If all anyone needs is a train fare or a safe cycle path to access the entire city, we will have both a thriving economy and a fairer one. Richer in every sense.

Forecasting the physical landscape of transport infrastructure, the city’s hardware, is relatively easy because these budgets are already set; we largely know what our cities will be like over the next decade. I will paint this picture later, but first let’s look back on the last major transport revolution in our cities: the birth of the car-centric city after World War II. Because we can understand this pattern better if we see how we got to this point and what, specifically, we are leaving behind.

New order

The war changed everything. In its wake so many things seemed inarguably, even permanently, settled. Technologically, the total superiority of the internal combustion engine and its even sexier new variants, jet and rocket engines, had driven the victory. Oil-burning machines were clearly so powerful, clean, modern and, above all else, American.

One city block can house as many people as an entire small suburb, and with a much lower carbon footprint.

And this, too, was now proven. The United States stood alone and above this ruined world, economically, technologically, but also culturally. It is hard to overstate the moral hegemony the US had acquired by 1945. Its machines were not only better, but also its ideas, its people, its ways of living — or was each better because of the others? Could we, too, through the simple act of imitation, all become rich and strong and good like Americans?

What, perhaps other than Coca-Cola, symbolised this more than the private car? Everything about this device seemed to perfectly express the American ideal. It is for the individual, not the collective, owned and directed by each driver, not restricted to a fixed route or timetable, available in a variety of shapes and colours to project personal taste for those that can afford it. An engine, therefore, both profoundly utilitarian and an expression of superiority and success; perhaps the perfect symbol and natural culmination of the triumph of capitalism. Even though it always relies on publicly funded roads and streets to function, the private car nonetheless seems to be the perfect embodiment of Pax Americana. We all still hear this formation today: Cars = freedom.

Postwar New Zealand cities, like the rest of the world, were largely unready for this. They were small and relatively compact, driven by steam trains and electric trams. City centres were dense and the streets and roads were modest because of the inherent spatial efficiency of these main transport modes; trams and trains can carry a lot of people (and trains freight) on relatively narrow right of ways.

Our cities had spread modestly during the first half of that century, with new suburbs linked through the extension of electric tramways. This was the revolutionary urban transport technology of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, connecting the bungalow and state house suburbs beyond the Victorian inner suburbs.

The Victorians, being the truest proponents of laissez-faire, allowed every aspect of life — industry, commerce, education, play, even waste disposal — to occur all at once and wherever. The disadvantages of this in an age of fairly toxic industrial practices and coal-fired energy led to the city beautiful movement — the urge to get away from the chaos and unpleasantness of the unregulated Victorian city. To move families away and apart to clean and green new pastures: the suburb. The tramway suburbs were conceived in this light; leafy, airy, separate.

This also of course fitted neatly with the ever-present industry of land speculation; the problem, however, was not a want of cheap land, but rather the need to efficiently connect these new areas to the old centres of industry, commerce, and society; the urbs to which these areas are sub. In New Zealand as in Britain and the United States, the first new dormitory suburbs were made possible by tramways and railways (cable-cars, too, in Wellington and San Francisco). And we can still see how these transport technologies shaped these places. Railway-oriented development is clearly patterned by a clustering around stations, but tramway suburbs are characterised by several more subtle features, which have left them with a timeless desirability.

First is the street layout. Trams, or streetcars, needed to run on coherent linear routes, which called for an orthogonal-grid street pattern (called ‘Jeffersonian’ in the US) wherever possible; it’s most visible in Christchurch, Whanganui, the isthmus in Auckland, but generally not easy to deliver on New Zealand’s folded topography. And yet even over difficult terrain this makes for a great interconnected street pattern for any sort of movement technology.

Then there are the stops: more frequent and less dominating than train stations, but still visible today by the extant cluster of several two- or three-storey shops with living above, built right up to the pavement to provide shelter and commerce for the traveller. It is these that saved the new suburbs from being monotone bedroom ’burbs. Even today, so many are still neighbourhood-enriching shops, cafes, and bars.

Thirdly, the streets are all connected by walkways. Semi-secret now, these were all carefully placed to ease connection by foot, especially to tram stops but also schools and shops and parks. So while they remain relatively low-density detached-house suburbs, these tram-built ’burbs are still at core successfully mixed-use, connected, and above all highly walkable.

Before the war, cars crept gradually into this world. Limited to the wealthy minority, they simply added an additional layer of mobility for those who could afford it. And because first the Great Depression, then the war, limited vehicle numbers to usually the local doctor, lawyer, and occasional successful businessman, both the exclusivity and (especially) the effectiveness of the mode were maintained. The car retained all its desirability through scarcity, and the roads and streets were kept efficient because most people were still riding the trams and trains. In fact, Auckland in the late 1940s, with its widespread and frequent tram system (‘Always a tram in sight’), reported the world’s highest proportion of public transport users in any first-world city.

Then came the revolution. From the late 1940s all across the world almost every city had widespread tramways and almost every city ripped them up. Only a handful retained them, most notably Melbourne and Toronto, always through quirks of local politics and public outcry, but even in these places their systems shrank back or were no longer extended until late last century when they became valued again.

No New Zealand city retained its tramway. The forces at work here were the same as everywhere: with rising car traffic the trams were blamed for the increasing traffic congestion; they were seen as old-fashioned (‘Streetcars are as obsolete as the horse and buggy’ — Toronto, 1966), criticised for being ‘inflexible’, which is to say un-car-like, and attacked by well-connected motorists’ groups and the growing automobile industry. What ultimately sealed their fate was the fact that everywhere the systems had not been invested in through the privations of (again) the Depression and war, and all were due major upgrades to vehicles and systems alike.

Even though Auckland’s trams, for example, were still extremely effective and running at an operating surplus, the need for major public investment doomed them in the face of the not-unreasonable idea that their market could be served just as well, if not better, by ‘modern’ diesel buses. But the removal of the tramways through 1949–56, and their replacement with buses, led to an immediate collapse in public transport use, one that has been described as ‘the largest decline in public transport patronage recorded over this period in any large city in the world’.3 Partly this was to do with the spread of car ownership, which began to accelerate in the 1950s as a result of increased availability and investment in motorways, but it was also because the buses did not have priority on the streets like the trams before, instead becoming ever more delayed behind ever more cars.

Slowly we discovered our road and street networks straining under the burden of taking every tramload of people and expecting them all to find space to drive a car, especially into the city. But by then it was too late — or rather, the growing mass of vehicles just underlined further that this was the future. In every year from 1946 until the oil crisis of the 1970s the price of crude oil fell, and the postwar economic boom expanded the number of households and businesses able to buy a car.

Naturally looking to our new American overlords for guidance (‘America’s most faithful disciple’),4 the chosen answer to this problem was an all-in commitment to a brave new world of dedicated motorways and car-parking structures, and to gift every existing piece of carriageway over to private car users. All while defunding and managing down our railways, and even those new buses, to near-oblivion.

This became the single-minded direction of all transport policies for the rest of the last century and into the current one. The 1955 Master Transport Plan used photographs of wide American freeways and clover-leaf intersections on bright sunny days and contrasted them with gloomily shot tram-filled Auckland city streets to great effect. It is still orthodox to consider that ‘transport policy = road-building’, and this was enshrined into funding policy; New Zealand is still the only country other than the US that ring-fences transport taxes for transport use (which quickly became understood specifically as road-building). And when it comes to transport choices, what we fed grew; New Zealand now has one of the highest rates of car ownership in the world.

Transport investment decisions always have urban form consequences. The Auckland Harbour Bridge created the North Shore suburbia in both fact and pattern. Because it is a road-only bridge, the new suburbs built in its wake are entirely on an auto-dependent pattern, hard (but not impossible) to now retrofit with alternative modes. The same goes for east Auckland over the Tamaki River, and the rest of the new suburbs built after the war. There was not even a right of way reserved for possible future rapid transit systems, so total was the belief in a car-only future.

Just a decade later, in 1965, more American consultants were hired to guide us, but this time they advised a ‘balanced’ rapid transit and motorway system, now that the folly of the imbalanced approach was already patently obvious. But the way our institutions were now set up there was no funding source for half of the programme, so the rail/bus rapid transit part of the De Leuw Cather plan was ignored while motorway expansion continued; this included the construction of the southern hemisphere’s biggest urban motorway interchange, Spaghetti Junction, which led to the complete physical severance of the city centre from its inner suburbs.

This worked as far as it went, but by end of century it had well and truly hit its limits. The need to revive an effective transit system in order to relieve this huge investment became all too clear as Auckland succumbed to the inevitable outcome of such an all-in car-only policy: the urban cancer of traffic congestion.

Additionally, the consequences of over half a century of this monotone policy is a monotonous world. Auto-dependent suburbs, like the tram-built suburbs before them, come with their own pattern language. Gone is the grid; the swooping cul-de-sac is king now, with no more compact two-storey corner shops and very few pedestrian short-cuts. What little amenity there is has been placed at driving distance and supplied with acres of parking — including, ironically, the gym and, unbelievably, the pub. The car not only conquers distance, but also enforces it.

The result is large swathes of dormitory zones, pepperpotted with enormous shopping centres, set back and separated from their communities by oceans of tarmac, all served by multi-lane highways and intersections uncrossable on foot. And this, too, created a cultural shift.

Auto-dependency is a very precise phrase. It describes a culture of addiction. People cannot imagine executing even the simplest of tasks in these areas without first grabbing their car keys. And this is not because of love or desire, as expressed in the inane observation that ‘Kiwis just love their cars’; it is because of design, because of policy. These new suburbs are incredibly difficult to use outside of a car. There’s nowhere safe to ride a bike, no efficient transit service, not even anywhere close by to walk to.

Furthermore, a key outcome of dependency is compulsive behaviours. These areas generate the most change-resistant politics, characterised by wildly overblown reactions to any plan to remove a car-parking space, or even add more movement options for the direct benefit of both locals and drivers. These reactions speak of irrational fears, of the addict concerned only about the fix.

This model comes arm-in-arm with appalling rates of death and serious injury from crashes, an epidemic of the diseases of inactivity, such as diabetes, and, for such a low population, wastefully high levels of traffic congestion. Economists estimate the annual cost of traffic deaths and serious injuries in Auckland at around $1.3 billion — about the same figure they come to for the cost of congestion. These are huge burdens imposed by our drive-only city planning decisions.

So now we are confronted with the paradox of trying to spread the freedom the car offers individually to everyone for all journeys; but driving is great until everyone is doing it. It worked so well, and was so direct and desirable, when most people were still on the spatially efficient trams and trains. Now that everyone drives, for every journey, it’s a bust. And traffic sure is democratic: we all get stuck in the same congestion, because we are that congestion. The six-lane Pakuranga Highway is the busiest non-motorway road in the country, uncrossable by foot, often maddening to use in a vehicle, without relief from any alternative. Destined to choke itself to death, it’s a monument to the naivety of postwar planning.

Both new suburbs and new highways exhibit a version of the ‘boiling frog’ metaphor in their life cycles. Both start out relatively clear — the new suburb still with something of the countryside it replaces about it, and the highway free-flowing to begin with — but their very success becomes their dysfunction. Additionally, all this driving out in the new suburbs never stays there; the freedom to drive demands access all areas, including the old tram-built suburbs, the even denser and entirely pre-car Victorian ones, and the city centre itself. This has led to massive retrofitting of motorways through established areas, with wholesale demolition and division of places and communities.

There is, however, a solution to these problems. And it doesn’t involve destroying what’s good about the last century’s world, but augmenting it with what’s currently missing. And not only that, but we’re actually doing it.

Revolution through evolution

‘Most people,’ said Bill Gates, ‘overestimate what they can do in one year and underestimate what they can do in ten years.’ This is absolutely true of cities, too.

Just because most change is incremental doesn’t mean for a moment that change ain’t a-comin’. Rather, I argue that we are in the midst of change as significant as that of the immediate postwar era; we are at one of those big hinge moments. Outside of natural disasters and wars (and the extraordinary recent Chinese urban explosion), even profound change is mostly incremental; over one year little appears to happen, but over ten, many gradual changes can add up to a lot.

Looking at the approved and funded transport infrastructure programme for Auckland, we can see how the city is currently in a phase of both accelerating growth and, even more interestingly, morphological change: it is plainly obvious that we will have an entirely transformed city by as early as the end of the 2020s. The completion of the City Rail Link will suddenly make Auckland something it has never been: a metro city. It will radically transform access to the biggest and fastest-growing concentration of jobs in the entire country (i.e. the city centre), especially for the people living in the west and south who most need this opportunity. People all along the Western Line will effectively be moved 20 minutes closer to the city centre, congestion-free. Truly transformational.

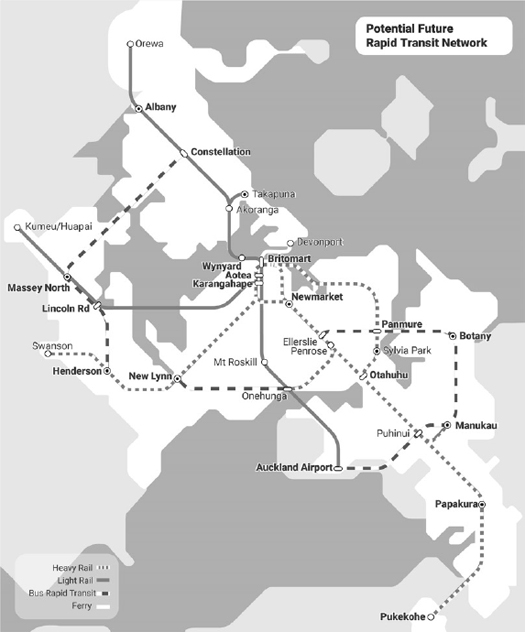

Along with light rail in Queen Street stretching up the length of Dominion Road and through Mangere, the combined capacity of these two systems will more than satisfy all the current and future growth in trip demand throughout the areas they reach. There’s also the coming North Western Rapid Transit system, likely to be light rail too, and the Eastern Busway, which speeds Pakuranga, Howick, and Botany people to the Panmure train station to join the improved rail network. Elsewhere on the rail system a dedicated shuttle from Manukau City via Puhinui Station will speed rail users directly to the airport, and the line south is being electrified at least to Pukekohe. Over the Harbour Bridge the Northern Busway is being extended within the decade with new stations and more right of way. Later in the 2020s work will have to begin on changing this system into a higher-capacity rail system with its own dedicated harbour crossing, just to cope with the sheer numbers using it. This, too, will most likely be modern light rail too, connecting to existing system at Wynyard Point and offering a direct trip from deep up the North Shore all the way to the airport.

Potential Future Rapid Transit Network. Map by Auckland Transport Alignment Project.

With these two separate but converging rail systems of similar capacities, and associated bus, ferry, and bike networks, Auckland will soon have a completely different shape, tone, and attractiveness. It will evolve from a city where car use is mandatory to one where the alternatives for so many more journeys are so good that driving becomes optional for more people at more times.

The freedom this extends to so many more people, and the opportunities for improved place quality all over the wider city, cannot be overstated. Really this is revolutionary, particularly compared to the late 2000s at the start of the SuperCity, or even more startlingly different from the mid-1990s, when we had no rapid transit, no Britomart, no busway, our lowest ever public transport use, and a vapid and near-moribund city with a weak centre.

Techno

Will this future be all autonomous flying cars and other futuristic machines? Or just more of the same vehicles, only fancier? Technology changes are always a significant influence on transport patterns and urban form, but separating which ones are likely, imminent, and transformative from those that are merely a smokescreen of evaporating wishes is not easy — especially as there is a veritable industry of techno-boosterism creating a kind of highly seductive distraction from more likely futures. Why think about currently available solutions for real problems when we can just wish them away with techno-fantasy?

To properly identify which new technologies will likely stick we need also look at trend-defining pressures from outside of the technology world: demographic, economic, and environmental dynamics that are likely to fit with some new or renewed technology to make it irresistible. True change occurs through a triangulation of present conditions, new pressures, and new opportunities. New technologies do need actual problems to address in order to stick.

A good current example of this is the 1) employment and living boom in city centres, plus 2) the need for environmentally positive, healthy, and spatially efficient movement systems, meeting 3) the rise of new compact battery technology; creating the e-bike boom. This cycling revival (which of course comprises both new and old technology) then drives political demand for safe-cycling infrastructure, changing city streetscapes the world over. Conversely, an example of a perfectly good technology that didn’t take because it addressed a non-existent problem is the Segway.

So it is important that discussions around new technology move beyond new hardware, such as new cars, because often these aren’t a technology revolution, merely an evolution of the last phase. I find talk of driverless cars ‘solving congestion’ to be absurd: other cars cannot be the solution to the problem of too many cars. There are plenty of ways that driverless cars could make congestion far worse. For example, we currently are mostly alone in our cars, with average occupancy at around 1.1 people per vehicle; true free-range bot-cars could lower this ratio to below one! Empty zombie cars nipping about to pick us up, or being sent on errands. Net result: clogged streets and kerbside pick-up and drop-off car battles.

It doesn’t have to be like this, of course; it is more likely, in my view, that the current trend of removing cars — driverless or otherwise — from busy centres will continue, especially as we add efficient transit options and safe cycleways to serve them. The proven economic, environmental, and social advantages of walkable dense centres is too valuable to waste on traffic now. So I expect the most effective new technologies to be ones that support this trend.5

Rather than all of us using driverless cars to access busy city centres, we are much more likely to use them to solve what’s known as the first mile/last mile problem: to connect to the new rapid transit stations and expand the reach of that new network. This will swish us over longer distances to or between centres and cities. We will do this because it will be cheaper and faster than each of us being in our separate little box, stuck in congestion of our making.

There have been driverless train systems in cities across the world for many decades, and this technology is next likely to spread to buses, as the driver is about half the cost of operating a bus, so the technology cost can be recovered. (Also, any vehicle operating on a fixed route will be easier to make work with this technology.) So driverless tech is likely to make existing transit services better and more cost-effective.

But technology also offers something other than just new vehicles.

The great city hack

A real technology revolution, a real disruption to the problems our current set-up creates, would really help us leave our cars behind, or at least leave them at home more often. And there is a clear model for what that looks like. It’s called MaaS: mobility as a service.

This is the move from each of us owning our own movement device, usually a car, to us using a variety of movement systems that we mostly don’t own. This may still be mostly cars, but it seems much more likely that once we start to gain the benefits from this model we will slide happily between different modes, leaving driving and congestion behind more often.

The ultimate benefit for many will be not having to own a car at all, or at least households being able to function well with fewer cars. The city that runs on private cars is shockingly expensive and inefficient. Our cars are, on average, parked 96 per cent of their lives. The nation spends about $5 billion in taxes and rates every year on land transport infrastructure, mostly roads, and we, the users, then spend another three times this, around $15 billion a year, buying, insuring, repairing, and fuelling them. Additionally, a dizzying amount of land is lost to more productive use by being reserved to store them several times over; where we work, shop, play, and live.

Unlocking even some of this cost by building viable transport alternatives and processes is urgent, not only because the drive-only city is unsustainable and failing through congestion and sprawl, but also because it will save everyone time and money. Replacing the annual $7 billion-plus we spend on imported liquid fuels for cars with home-grown electricity offers a huge economic benefit to us individually and collectively. The power companies are extremely keen to supply more electrons for transport use, and we have plenty of potential capacity to generate all we need for this.

The cost of transport lands disproportionately on the poor. Transport poverty is the flipside of the housing unaffordability coin. It is cripplingly expensive to have to live with no money; the only available housing in Auckland is now at the fringes of the city (now that inner-city value has been rediscovered).6 The lack of good transit alternatives usually means every member of the household needs a car, and the lack of capital means that money for these cars is typically borrowed, often at usurious rates. Cars are, of course, depreciating assets. People are often only one crash or breakdown away from transport system–induced immobility, unemployment, and further poverty. And all along the way being forced to make horrible choices — like sacrificing food money for gas, or giving up their homes entirely and living in their cars. So auto-dependent cities are inequitable cities. Being able to choose to use a car when it suits is a great freedom, but a greater freedom is the ability to choose to not have to drive at all times and for every journey.

The world over, the great city problem is the misalignment of economic costs and benefits. This is especially the case with transport. For example, whenever we drive a car in a city we impose huge burdens on every other citizen: we foul the air they breathe, we hog the public realm we call streets, we delay them in their attempts to get places, or the goods they need, or even that ambulance that their very existence depends on; sometimes we even maim or kill them.

Conversely, everyone who chooses to jump on a train or a bike instead frees up those same streets for others, improves their own well-being so they will be less likely to be a burden on public health services, refrains from consuming fossil fuels that are cooking the whole biosphere, and, especially the bike users, is much happier.7

But the challenge is that these costs and benefits are not there directly in financial form for each citizen, helping to guide their choices. We do of course collect rates and taxes and use some of that money to fund the positive things — building bike lanes, or subsidising transit — and to mitigate the bad outcomes, but this is very imprecise, and at a remove from the choices we make.

Imagine if there were a way we could reward that transit user or bike rider precisely in proportion to the wider value they offer, and charge the car user accurately for their burdens on others? Not in a punitive way; simply accurately. The value creators earning credits, the consumers spending them. This would be sure to change behaviours.

To me this is the city hack that will best fit the coming new transit and cycling infrastructure. After all, we only need a relatively small mode shift from driving to the alternatives to largely de-stress and humanise our streets and our habits. Even a 10 per cent shift from current levels would make a profound reduction in traffic delay and take a big bite out of our proposed road-widening/extending expenditure. And, properly done, this gamification of urban travel choices is likely to shift more than that. Every cost-conscious user — every kid, teen, student, elderly person, for starters — will be highly incentivised to shift and earn credits.

And everyone who chooses or needs to still drive will have the true cost of that to pass on or balance with other positive choices; tradies and delivery companies will have quicker journeys to trade off against the charge. This, of course, needs to come with the massive upgrade of the quality, quantity and spread of the alternatives, or it will lead to unfair outcomes for lower-income households. System design is critical here. And so is data privacy. But new technology does offer the hope for solutions along these lines.

To really be equitable and effective, the system needs to know exactly how everyone is using the city and when. This already happens to an alarming degree for those with smart phones, but in a problematic way. That data is extremely valuable to some users, including unscrupulous ones, as we have seen recently. The tech challenge is to be able to collect this data, but also to leave the control of it solely with the individual, not with private companies, or even transit agencies.

We know that these ideas around the social contract are being worked on, but how well and how soon they may become current and accepted is hard to say. We do know we need new movement options now if we are to shift away from the status quo. New technology to help us make better transport choices can work only if the options are there to be chosen. Happily, as we have seen, that will indeed soon be the case in Auckland. Can it also spread across urban New Zealand?

Beyond Auckland

Wellington, long New Zealand’s most urbane city, is waking up its urban soul again after a long period of trying hard to compete in the auto age. The city is intensifying again, and the pressure is on to wrestle back those streets for people, and to break the terminus of the train station by extending light rail past the hospital to the airport, while also adding a bike lane network. Wellington’s spectacularly restrictive topography has always given it an intensity beyond its size, so it is good to see the city embracing that pattern again rather than trying to ignore it.

Cycling is also Christchurch’s great opportunity. This once world-leading riding city could regain that status once more, and great work is being done there. But otherwise it is of course dealing with the earthquakes that devastated its centre, and the rebuild that reinforced a particularly extreme edge-city pattern: malls, sprawl, and driving. Until housing returns at scale to the centre, our second city will remain firmly suburban.

Fascinatingly, both Hamilton and Tauranga suddenly face very interesting opportunities as a result of the Auckland spillover. People escaping the overheated Auckland property market have added all sorts of growth pressures to these two cities, and this is stimulating a rethink.

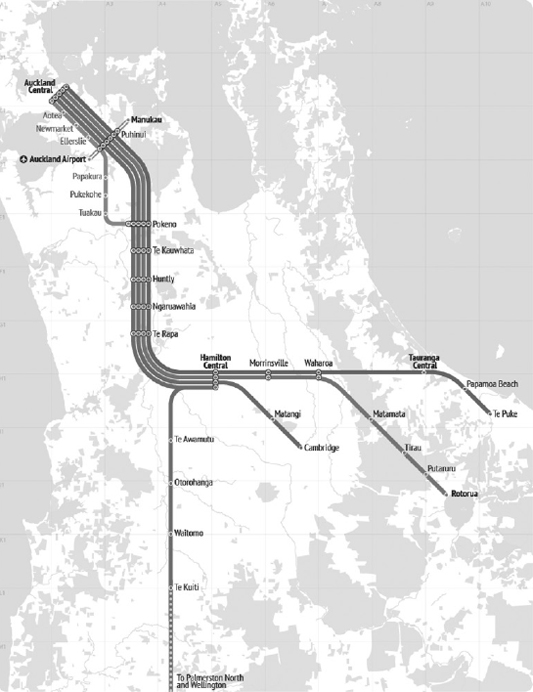

A regional network of rapid intercity rail lines to connect the peoples and economies of the upper North Island. Source: Greater Auckland

Tauranga is more constrained by its setting than its current development pattern belies, and would benefit enormously from adding to its extensive, and traffic-inducing, motorways with a simple but efficient and effective rapid transit network — in particular by exploiting the natural spine of Cameron Road across to The Mount one way and Papamoa the other. This would enable new patterns for growth on a less resource- and capital-hungry model.

The change that’s most exciting for Hamilton has even more to do with its big sister up State Highway 1. The coming return of intercity passenger trains between these two cities, and beyond into the Bay of Plenty, offers both a chance to help fix Hamilton’s long-struggling city centre, and to shape a better, more compact development pattern in satellite towns outside the cities. Hamilton’s centre desperately needs both a focus and a desirable way of accessing it without bringing more cars. A city centre rail station can be that point and the start of that change.

And instead of all the towns on the Hamilton–Auckland corridor just spreading in formless farm-eating sprawl, an effective rail service can enable a good satellite town–country lifestyle at an affordable price. Different members of these households could work and study in either city without having to suffer the unpredictable and soul-sapping highway commute each day and without the financial burden of buying more cars than is necessary. This simple revival, done properly, could be transformational for delivering desperately needed new housing and shaping better, more sustainable development.

Conclusion

Transport infrastructure is merely an enabler, a means to an end; however, especially in cities, it is also an incredibly powerful one. It can and does proscribe so much of our existence; shapes so much of our world, our possibilities, the quality and even the length of our lives. And we now stand at the beginning of a great shift that should enable a much more vibrant, productive, and sustainable urban realm, one that both supports, and more evenly spreads, increased prosperity and well-being.

Cities that are right-shaped for the demands of this century.

Relatively soon we will look back on our currently car-drenched and exhaust-filled streets as unthinkably backward and unbearable. This set-up, this invention of the second half of the twentieth century, the auto-dependent dispersed city, is in fact already dead; it just doesn’t know it yet.

1 Paul Mees & Jago Dodson (2001). An American Heresy: Half a century of transport planning in Auckland. Presented to NZ Geographical Society & Australian Institute of Geographers conference, University of Otago, Dunedin.

2 David Owen (2009). Green Metropolis: Why living smaller, living closer, and driving less are the keys to sustainability. New York: Riverhead (a Penguin imprint).

3 Mees & Dodson (2001).

4 Ibid.

5 Jeff Speck (2012). Walkable City: How Downtown can save America, one step at a time. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

6 Alan Ehrenhalt (2012). The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City. New York: Knopf.

7 Charles Montgomery (2013). Happy City: Transforming our lives through urban design. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.