PROPER CARE OF THE PREGNANT COW IS IMPORTANT for healthy offspring and future reproductive ability of the cow. The pregnant cow needs adequate nutrition to provide for the developing fetus, and she needs vaccinations against diseases that could harm it.

Most cows calve in spring, so they go through winter while pregnant. What you feed and how much will be determined by the severity of the winter and the cows’ stage of pregnancy during coldest weather. If cows are in the crucial final trimester of gestation and weather is still cold, you must feed adequately to provide proper nutrition not only for body warmth and maintenance but also for the demands of the rapidly growing fetus, the cow’s milking ability after she calves, and her fertility after calving.

Cows too thin at calving take longer to recover and start cycling. They may be late to rebreed, with lower conception rates than cows in moderate to good condition at calving. If a cow is short-changed on nutrition before calving, the malnourishment can adversely affect the weaning weight of her calf. Fall is a good time to carefully evaluate the condition of spring-calving cows. Watch them closely through winter to make sure your feeding is on target. It is very difficult to “pick up” a cow’s weight after she calves and is nursing, since the demands of lactation require good nutrition; she puts the extra energy into milk instead of body weight. It also takes energy to cycle and come back into heat. Reproduction will not occur if a cow is too thin. Mother nature considers reproduction a luxury that can occur only after a cow’s other needs are met with adequate nutrients to maintain her own body weight and supply enough milk for her present calf.

To get good ability to breed back quickly yet avoid excessive feed costs, evaluate body condition closely at least 60 days before calving and again at calving so you can make feed adjustments. Each body condition score is equivalent to 60 to 80 pounds (27–36 kg). A fat cow with body condition score 7 can coast along on poorer feeds and even lose about 140 pounds (63.5 kg) of weight (down to score 5) without detrimental effects, whereas cows with body condition score 3 need to gain 140 pounds (63.5 kg) before calving if you expect them to rebreed.

EVALUATING BODY CONDITION

Evaluate body condition when cows are put through a chute where you can get your hands on them to feel the fat covering shoulders, ribs, hips, and tail head. They may not be as fat as they appear, especially if long hair covers ribs and shoulders. The hand is better than the eye for judging fat cover. Cows are generally scored as follows: 1–3 is thin; 4–6 is moderate; and 7–9 is fat. The most healthy and fertile cows (and most able to properly feed their calves) are generally those with body condition scores between 4 and 7.

Body Condition Score

1. Emaciated; no fat can be felt along backbone or ribs

2. Very thin; some fat along backbone, none on ribs

3. Thin; fat along backbone, slight amount on ribs

4. Borderline; some fat over ribs

5. Moderate; fat cover over ribs feels spongy

6. Good; spongy fat over ribs and some around tail head

7. Fleshy; spongy fat over ribs and around tail head

8. Fat; large fat deposits over ribs, around tail head, below vulva

9. Obese; vast fat cover (may have breeding and calving problems)

You do not want cows losing a lot just before or after calving. Even though they have the same body condition at calving, the cow gaining weight is better programmed for fertility and reproduction than the cow losing weight. Each 10 percent of body weight lost before calving can delay the first heat period by about 19 more days.

Green pasture supplies all the nutrient requirements of the pregnant or lactating cow except salt (and certain minerals, if your region is short), so your task is easier when calving after green grass is plentiful.

Any cow on green pasture during summer won’t be short on vitamin A, but if pastures were dry and brown in fall or summer she may need supplemented vitamin A during the last part of gestation or during early lactation.

Salt should always be provided since it is the one mineral never found in natural feeds and forages. Calcium is important to the pregnant cow, and even more crucial during lactation. It is well supplied by good-quality forages such as grass and hay. Some beef cows wintered on mature grasses or crop residues may need phosphorus. This mineral is most important to the pregnant cow in the last 2 or 3 months before calving and the first 3 months afterward (until she is rebred). Trace minerals are crucial for a strong and healthy immune system.

During the last 2 months the fetus makes 70 to 75 percent of total growth, needing extra nutrients. The last 50 days of gestation are most crucial for the fetus. If a calf is born weak and small due to undernourishment of the cow, it may not be strong enough to get up and nurse in time to gain benefits from colostrum (the cow’s first milk) — and the colostrum may be low in antibody protection because of poor condition of the cow.

Health care for beef cows includes an adequate vaccination program on a regular schedule. Some vaccines should be given during pregnancy, and others should only be given to open cows. Certain live-virus vaccines can cause a cow to abort if given during pregnancy. Many serious cattle diseases can be prevented by vaccination. Some can be prevented with calfhood vaccinations, but most require an annual or semiannual booster shot to keep the cow’s immunity strong throughout her lifetime. Talk with your veterinarian and become familiar with proper procedures for vaccination, which vaccines to give, and what time of year (and in what part of the cow’s reproduction cycle) they should be given.

If you have just a few cows, they are probably all in the same pen or pasture. This works fine unless one or two are heifers or young cows that need extra or higher-quality feed. Find a way to feed the young ones separately. If you don’t have space to put them in a separate pen, let them into the corral once a day for special feeding — alfalfa hay, grain, or pellets.

Pregnant yearlings and two-year-olds that have weaned off their first calves are still growing and need more energy and protein than mature cows. An old, thin cow may need pampering also. If your older cow is having trouble maintaining her weight, put her with the young ones so she can benefit from the special feeding program. Effects of cold weather on nutritional requirements are covered in chapter 6.

Some diseases cause abortions if you fail to vaccinate your cows. One is leptospirosis. Vaccinate all cows annually for this; many vets recommend twice-yearly vaccination. This vaccine is safe to give during pregnancy. Vaccinations are discussed more fully in chapter 7; check with your vet to make sure your pregnant cow is adequately protected against diseases that might affect her unborn calf.

Certain vaccines stimulate a cow to create antibodies against diseases that cause serious problems in newborn calves — such as diarrhea caused by rotavirus, coronavirus, or E. coli bacteria, or enterotoxemia caused by C. perfringens. If you vaccinate the cow 2 to 4 weeks before calving, she will develop antibodies and her colostrum will contain a rich supply. This gives the calf temporary protection from these diseases if he nurses immediately after birth; many antibodies from colostrum are absorbed directly into his bloodstream.

You may not have a problem with scours if you have a clean place for cows to calve and an uncontaminated pasture for cows with baby calves. But if you bring in cattle with intestinal infections, you may soon have diarrhea in young calves unless you vaccinate cows in late pregnancy. Vaccination cannot prevent all types of scours, but in some cases it can be helpful. Your veterinarian can diagnose various types of diarrhea in calves and may recommend vaccinating cows before calving.

Vaccinate in series. If the cows have never been vaccinated for these problems, they may require a series of two injections, a few weeks apart, to stimulate adequate antibody production. In following years a single booster shot will be adequate if given 2 weeks or more before calving. With one type of vaccine, the first dose should be given 6 to 8 weeks or more ahead of calving, at least 2 weeks before the second dose. The second dose should be given 2 to 4 weeks before calving.

Check your records to see when you put the bull with the cows and when they might begin to calve. First-calf heifers, or any purchased cows that have not had the vaccine in previous years, should receive their first dose 3 to 4 weeks ahead of the precalving booster shot (or about 6 to 8 weeks before calving). Write on your calendar when to give this early shot to your heifers and when to give the booster shot to the whole herd (2 weeks before the beginning of calving season).

After you vaccinate, count 45 to 50 days from the actual vaccination date and make a note on your calendar to revaccinate if certain cows in your herd have not yet calved by then and need another booster shot. The actual timing (and whether you need to give one or two doses) may vary, depending on the brand and type of vaccine. Read the labels and check with your veterinarian to figure out the most appropriate type of vaccine for your herd and the proper timing of injections for optimum antibody production in colostrum.

VITAMIN A SHOTS

Vitamin A is essential for healthy epithelial tissue (the membrane that lines internal organs of the body). If cows are deficient in vitamin A, calves may not be strong and healthy at birth. Severe deficiency may result in calves being born dead. If feed is dry from drought, bleached by too much moisture, or more than 2 years old, it may not contain enough vitamin A. This can be resolved by giving pregnant cows an injection of vitamin A a few weeks before calving. Keep an eye out, however. Some cows have adverse reactions to this injection.

Many things can go wrong in pregnant cows. Some result in abortion, birth defects, calving difficulty, or subsequent infertility. Some of these problems are uncommon and you may never encounter them, but knowing about them may enable you to prevent them or to properly treat a cow if they ever do happen.

Abortion is the expulsion of a premature live fetus before it reaches a viable stage of life, or expulsion of a dead fetus at any stage of gestation. Many early abortions take place without being noticed; the embryo or fetus isn’t large enough to be easily seen.

In the cow, abortions before the fifth month often have little external sign and are seldom followed by retained placenta. But abortions after the fifth month are often accompanied by retained placenta; the cow fails to shed the fetal membranes for several days after losing the fetus. Thus late-term abortions are more noticeable; the cow has membranes hanging from the vulva.

Most abortions occur during the last trimester, but it’s not always easy to determine the cause. Some abortions of unidentified cause are due to hormone imbalances or steroid release within the body due to stress. The stockman usually blames a fall on ice or fighting and being knocked around by other cows. Any severe stress can trigger release of hormones that start premature labor. Usually when a cow aborts after injury, it is stress (from pain, inflammation, etc.) that triggers the abortion rather than injury itself; the uterus and its fluids cushion the fetus well and protect it from trauma, even if the cow herself is seriously injured. Most abortions are due to some other cause.

An injection of dexamethasone during late pregnancy often causes the cow to go into labor, and the calf is born too early to survive. Dexamethasone is sometimes given to reduce swelling, inflammation, and pain from injury or disease, snakebite, or other problems. Never give dexamethasone to any pregnant cow, especially in the last trimester of gestation.

High fever may also result in abortion, as can poisons, such as iodine. Sodium iodide (sometimes given intravenously to treat bony lump jaw) should not be given to a pregnant cow. Flushing out an abscess with iodine solution may also be unwise. It is better to play it safe and use a less toxic disinfectant or antiseptic solution.

Eating moldy hay or silage can also cause abortions. Some types of mold are most deadly to the fetus during the third through seventh months of gestation, whereas molds of the aspergillus family usually cause abortion during the last trimester. Molds are thought to cause between 3 and 10 percent of all abortions in cattle. If feed is moldy, it should not be fed to pregnant cows.

Most late-term abortions are caused by infections. Under normal conditions, about 1 out of every 200 cows will abort for some reason or another, and this is no cause for alarm. But if abortion rate in a herd rises above 1 or 2 percent of the herd, there is a chance that infection or disease is involved. Some diseases can be prevented through vaccination and some cannot.

The most common cause of abortion in cattle worldwide is Bang’s disease (brucellosis), except in countries where it has been controlled by vaccination. Incidence of brucellosis in cattle in the United States was 11.5 percent in 1935 but dropped to less than 0.5 percent by 1970 with diligent vaccination. Because of the threat to human health, a rigorous program to eliminate the disease in cattle was begun as soon as a vaccine was developed for cattle. In humans, brucellosis causes undulant fever with recurring symptoms of fatigue, fever, chills, weight loss, body aches, and chronic cases with arthritis, emotional disturbances, and attacks of the central and optic nervous systems.

Humans get brucellosis from infected animals or imported dairy products. Natural hosts are cattle, hogs, goats, bison, and elk. Bang’s in U.S. cattle has been nearly eradicated by vaccination of heifers but will never be completely eliminated as long as there are problems in wildlife. Bison and elk in Yellowstone Park, for instance, carry the disease and pose a threat to livestock whenever they come out of the park and mingle with cattle or contaminate cattle pastures.

Brucellosis in cattle causes abortion in the last trimester of pregnancy and a subsequent period of infertility. Do not buy females that didn’t have their calfhood vaccinations (unless you live in a brucellosis-free state where vaccination is not required), and vaccinate all heifer calves within the proper age limit (before 10 months of age). Brucellosis is preventable, but as long as wildlife continue to harbor it there will always be some risk.

The most common cause of infectious abortion in cattle today in the United States is leptospirosis, caused by bacteria that affect many kinds of animals as well as humans. The bacteria are spread by urine of sick and carrier animals contaminating feed and water. The bacteria enter the cow through breaks in the skin on feet and legs when walking in contaminated water or through nose, mouth, or eyes by contact with contaminated feed, water, or urine. About 70 percent of infected cows show very little sign of sickness, whereas about 30 percent may show fever, loss of appetite, reduced milk production, jaundice, anemia, or difficulty breathing. In severe cases, the cow may die. Young cattle are usually more severely affected than adults. After recovery from the acute period of illness, the animal sheds bacteria in urine for several months, remaining a source of infection for other animals.

Lepto bacteria affect unborn calves; if a pregnant cow gets lepto during the last half of gestation, she will likely abort 1 to 3 weeks after recovering from the acute stage of the disease. Even if the cow did not appear sick, she may abort. Incidence of lepto abortions in an exposed herd may vary from 5 to 40 percent of the cows, depending on number of susceptible cows in the last half of gestation. Abortions from lepto often cause infection of the uterus and retained placenta, but cows usually recover and breed again. Not all infected cows abort. Sometimes a cow gives birth to a live, weak calf that dies within a few days.

A vaccine against five of the most common types of lepto that cause abortion in cows is available, and another vaccine for one of the other types that’s not in the five-way product. These vaccines provide immunity for about 6 months. For good protection, cows should be vaccinated twice a year, since lepto can cause abortion at any stage of pregnancy.

Another cause of third-trimester abortions is infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR, often called red nose), caused by the Herpes virus and similar to rhinopneumonitis in horses and Herpes simplex in humans. It often causes upper respiratory disease with fever; depression; lack of appetite; nasal discharge; reddened nasal membranes; coughing; ulcers in the nose, throat, and windpipe; and sometimes secondary pneumonia. IBR is also an immunesuppressant, which makes cattle vulnerable to other diseases.

If a cow is pregnant the virus may infect the fetus and cause abortion. Abortions from IBR may occur anytime during gestation but are most common during the second half. In a herd outbreak, more than half the cows may abort, depending on the number of susceptible cows in advanced pregnancy. Cows may or may not show signs of respiratory disease; often the only evidence of IBR in adult cattle is aborted fetuses. Abortions may occur several days or even weeks after the actual infection.

Another cause of abortion is bovine virus diarrhea (BVD). It causes abortion or mummification of the fetus (the fetus dies but is not expelled and remains encapsulated in the uterus) or calves carried full term but born with abnormalities (eye lesions, partial hairlessness, etc.). The BVD virus can also inhibit a cow’s immune system and make her susceptible to other infections such as lepto or IBR, even though she may have been vaccinated against them. The cow aborts from another infection because her immune system is so depressed from BVD that she has no immunity. Many outbreaks of lepto, IBR, clostridial diseases, and other problems are due to BVD infections that prevent development of immunity from vaccinations.

Intranasal vaccination (sprayed up the nostril rather than injected into muscle) can halt an epidemic of IBR but may not be effective immediately in stopping abortions, since some fetuses have already been infected and can be aborted after vaccination. The intranasal vaccine is safe for pregnant cows or calves nursing pregnant cows, whereas injected modified live-virus vaccine may cause cows to abort. Abortions due to vaccination usually occur 2–10 weeks after the injection. The best approach is to vaccinate the cows each year when they are not pregnant (after calving, before rebreeding) and to vaccinate young stock at weaning time to start building immunity. If calves are vaccinated while still nursing their mothers, intranasal or killed vaccine should be used. Otherwise the live-virus infection (given to the calf to stimulate his antibodies against the disease) may be transmitted from calf to cow and the cow may abort.

The best way to prevent this is to vaccinate all heifers at 9 to 10 months of age so they develop immunity against the BVD virus. In many herds, it may also be necessary to give all cows an annual vaccination with modified live virus after calving and before rebreeding. You can also give killed vaccines after a cow is pregnant. Discuss this with your veterinarian.

Other diseases that cause abortions include listeriosis, from a bacterium carried by rodents and other animals. It can also be present in silage. There is no way to prevent this disease by vaccination, but it is not very common.

Some abortions are caused by venereal diseases. Vibriosis can be transmitted at the time of breeding from an infected bull. The infection causes death of the embryo early in pregnancy. Often the embryo dies so early that the cow returns to heat and you think she didn’t conceive, but in some cases the fetus is carried for a few months and then aborted. Generally the cow develops immunity and is able to rebreed later and carry a calf, but it means she will calve much later in the season than you planned.

Many abortions have no detectable cause. But if a cow aborts, try to determine the cause so that if it is due to infectious disease you can vaccinate or change your management program to prevent further incidents. Your vet can send the freshly aborted fetus (if you find it) to a diagnostic laboratory; in some cases blood samples from the aborting cow, or the placental membranes themselves, can be analyzed.

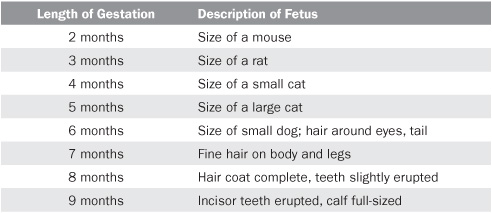

CHARACTERISTICS OF ABORTED FETUS TO DETERMINE AGE

This bacterial disease can be prevented by vaccinating cows and not using infected bulls. It is spread from an infected cow to susceptible cows by the bull, who becomes infected himself. Bulls can be carriers for many years. If you have cows in a community pasture, vaccinate them. If you start your herd with healthy cows, use only virgin bulls, and never have them bred by someone else’s bulls, then you won’t have to worry about this venereal disease. If you are buying, borrowing, or leasing a bull that has already been used on cows, make sure that he is not infected with vibriosis.

Another disease that causes abortion is trichomoniasis, spread by infected bulls. This disease occasionally causes late-term abortions, but more often the cow aborts in the first 90 days. Usually no visible sign of abortion is present when the fetus is this tiny. The cow is infected at breeding, aborts later, and may or may not breed back. A bull can be checked by a veterinarian to see if he is infected. The best way to protect your herd is to use only virgin bulls or bulls that have been tested and found free of trichomoniasis.

Toxins in certain plants can cause abortions. Locoweed can cause abortions or birth defects, as can several types of lupine and broomweed (thread-leaf snakeweed). A common cause of abortion is cows eating ponderosa pine needles. Ponderosa pine grows in all states west of the Great Plains and in western Canada. Cattle may eat needles when hungry or cold, when seeking shelter among pine trees during storms or being herded through timber, when grazing around the trees, or when being fed hay on top of fallen needles.

Abortion may occur as early as 48 hours after a cow eats pine needles, but some cows abort as late as 2 weeks after. Just a few needles can be enough to cause abortion. A cow might deliver a live calf if near the end of her pregnancy. Cows aborting after eating pine needles retain the placenta. Weak uterine contractions, excessive bleeding, and incomplete dilation of the cervix may complicate some abortions; the fetus may not be properly expelled. Some cows develop toxemia and die before or shortly after the abortion unless given prompt treatment. Some may have a bloody discharge but don’t abort. They may later give birth to small, weak calves, or have little or no colostrum when they calve.

Sometimes a poison or plant eaten during pregnancy results in birth defects rather than abortion. One example is lupine. This wildflower blooms early and the blooms stay on into summer. Some species are harmless, but others contain poisonous alkaloids that cause deformities in unborn calves if eaten by cows between 40th and 90th day of gestation. Four of the most common poisonous species are silky lupine, tailcup, and velvet and silvery lupine. The calves are born with crooked legs, twisted spine, cleft palate, or other skeletal defects. Some are so malformed they cannot be born and must be delivered by caesarean section or cut in pieces to be removed from the cow. Some survive, but others are so deformed they must be humanely destroyed.

Lupine grows on foothills and mountain pastures in every western state. Poisonous species are dangerous to livestock from the time they start growing in spring until they dry up in the fall. The seeds can be toxic in late summer or fall. Abortions can also occur at any stage of gestation if a cow eats too much lupine. Lupine can be safely grazed after pods have released their seeds.

Usually a cow carries her calf to term with no problems. But occasionally something kills the fetus and it is not expelled. When a fertilized egg or embryo dies early in gestation, it is absorbed in the uterus and the only sign of loss is a slight discharge from the cow’s vagina. The cow recovers and resumes her heat cycles.

Serious infection in the uterus may occur when the fetus dies after the first trimester and is not expelled. The cow may start discharging pus or fragments of the rotting fetus. If you notice a pus discharge or decayed tissues being expelled, have your vet examine the cow. The cow’s system has tried to abort a dead fetus, but the cervix did not dilate enough for it to pass through, or the fetus was in an abnormal position and could not come through.

If the cervix opens when the fetus dies, bacteria enter the uterus and the dead fetus is invaded by the pathogens and begins to decay. Usually the cow shows signs of intermittent straining for several days and develops a foul-smelling discharge. She may have a fever and go off feed. She will need antibiotics, and the decaying fetal material may have to be removed by your vet. If the rotting tissues can be safely removed and the infection cleared up, she may recover and rebreed after a few months. But a serious infection from this type of abortion can be fatal to the cow, so do not delay in calling your vet if you suspect a problem.

Fetal death after the first trimester does not always result in abortion or decomposition. If the cervix does not open and infection does not enter the uterus, the fetus does not decay. The uterus reabsorbs the placental and fetal fluids; the fetus dries out and mummifies. This sometimes happens with twins. One dies and mummifies and the other continues to develop. The live calf is usually born normally when it reaches full term, and the mummified twin is discovered at that time.

More commonly the dead calf is a single (not a twin), and due to a hormonal imbalance the uterus continues on as if pregnant (the cervix does not open; the dead fetus is not expelled). The uterus contracts and tightly encloses the fetus. The longer the condition exists, the drier, firmer, and more leatherlike the fetus becomes.

The mummified fetus may remain in the uterus for months beyond normal gestation time or be expelled shortly before or near the expected end of the pregnancy. If you ever have a cow that seems pregnant (she is bred and ceases her heat cycles) but approaches calving time with no evidence of being ready to calve, or goes past her due date with no evidence of readiness (no udder development, no relaxation of vulva, etc.), have her examined by your veterinarian. If she has a mummified fetus, the vet can induce labor to expel it.

Hydrops amnii — production of too much fluid around the fetus — occasionally occurs in pregnant cows. The cow may become large in the belly long before calving time. This condition is sometimes due to a genetic abnormality resulting in a defective fetus. In a severe case the cow does not survive unless the pregnancy is terminated early. If you ever have a cow that “looks like she has triplets” well before her due date, have her examined by your veterinarian. She may continue to produce too much fluid around the calf, with her abdomen becoming so large that she cannot get around. In some cases labor must be induced and the thickened fetal membranes manually broken.

Prolapse of the vagina is a more common problem in pregnant cows than in open cows. This occurs a few weeks or even a month or more before calving. Some cows, especially Herefords, have a structural weakness that allows part of the vagina to prolapse during late pregnancy. This is an inherited problem. Some bulls sire daughters that prolapse easily, and they may pass this tendency to their offspring.

The main cause of vaginal prolapse is pressure and weight of the large uterus in late pregnancy. When the cow is lying down (especially if her hind end is slightly downhill), this pressure may cause vaginal tissue to prolapse. She may pass manure while lying there and strain a few times, and the tissue bulges out.

A mild prolapse — a bulge the size of an orange or grapefruit — usually goes back in when the cow gets up. But if she prolapses each time she lies down or strains while lying there, the tissue may be forced out farther. Just the presence of a small prolapse may stimulate the cow to strain, making the situation worse. She has a mass of tissue bulging out, becoming damaged, dirty, and possibly infected.

The vaginal wall is not a sterile environment, so infection is not the primary concern. The problem is that once these tissues are turned inside out, blood supply from the prolapsed area becomes restricted, making the tissue swell. The longer it is outside the body, the more it swells and the harder it is to put back in. If the cow is near calving, this swelling may make birth more difficult. A vaginal prolapse should be replaced as soon as possible, even though the immediate condition is not life-threatening.

Some heavily pregnant cows strain when passing manure or from irritation of a mild prolapse, making a small problem into a larger one. If the prolapse is large — the size of a volleyball — the bladder may become involved; the cow cannot urinate until the prolapsed tissue is pushed back inside. She may strain to urinate, aggravating the problem more.

If the tissue has been prolapsed several hours or longer, it will be covered with manure. It should be washed before being pushed back in, or irritation from contamination will cause inflammation and infection. Restrain the cow in a chute. Wash the prolapsed tissue very gently with warm water and a mild disinfectant like Nolvasan or even Ivory soap. Rinse it thoroughly, then push it in. If the prolapse has been out for more than a day before you noticed it, the tissues may be dry and dirty, and harder to clean up and push back in.

Vaginal prolapse

Do not mistake the bulge of pink vaginal tissue for an amnion sac, especially some dark night when you are checking the ready-to-calve cows. The amnion is a thin membrane filled with clear fluid, encasing the calf being born. If you are in the habit of slicing this sac (to prevent suffocation of the newborn in instances where the sac does not break), make sure of what you are slicing!

Some cows repeatedly prolapse the vagina every calving season during late pregnancy, even after the tissues are replaced. To correct this chronic problem, put stitches across the vagina to hold it in after you’ve cleaned up the protruding ball of tissue and pushed it back. If you are hesitant to try this, have your vet do it. He will use a large, curved suture needle and umbilical tape (wide cloth “string”); it is less likely to pull out than regular suture thread.

Stitches should be anchored in haired skin at the sides of the vulva. This skin is thick and tough and won’t tear out as easily as the skin of the vulva. It is also less sensitive — less painful to the cow when stitches are put in. It takes at least three cross-stitches to keep the vulva safely closed so the inner tissue cannot prolapse if she strains. The cow can urinate through the stitches, but the vulva cannot open enough to prolapse.

If the cow is stitched, watch her closely as her time comes to calve. Stitches must be removed when she starts labor or she will tear them out or have difficulty calving. When she goes into labor, stitches can be cut and pulled gently out. Cut them with surgical scissors, tin snips, a very sharp knife — whatever you have on hand to cut them quickly and easily without poking the cow.

Once she has calved, the pressure that caused the prolapse will no longer exist and she generally won’t have any more problems until late in the next pregnancy. Most stockmen cull a cow once she has prolapsed. If she is a gentle cow, not difficult to work with, and has really good calves, you might decide to keep her and put up with the yearly nuisance. But offspring from such a cow should never be kept for breeding, because they will probably inherit this structural weakness.

After washing the prolapsed tissue and pushing it back in, place several stitches across the vulva opening. Use umbilical tape to anchor the sutures in the haired skin alongside the vulva. The sutures will prevent recurrence of the prolapse.