Seasons of the Saeculum

Time is cyclical, a series of interlocking circles that follow the same pattern year after year, century after century. The moon waxes and wanes every month as it goes through its phases—first quarter, full, last quarter, new—predictably and regularly. The Wheel of the Year turns. While the cycle manifests itself differently in different climates, it follows the same pattern year after year. For example, in ancient Egypt there was the season of the inundation, followed by planting and growth, followed by harvest, followed by the dry season waiting for the flood again.1 In temperate climates we experience spring and planting, summer and growth, autumn and harvest, winter and cold. The wheel turns on and on, year after year, century after century.

There is also a larger wheel, the wheel of human life, which is composed of four phases of life. The Romans called these pueritia (childhood), iuventus (youth), virilitas (maturity), and senectia (old age). According to Roman writers, these phases correspond with the seasons. We are children in springtime, are filled with the passions of youth in summer, grow to maturity in autumn, and grow old with the year in winter. The wheel of our lives turns just as the Wheel of the Year does, and unless we die young and untimely, we will experience all four seasons.

However, there is an even larger wheel that the Romans called “the Great Wheel,” or the saeculum, the wheel of generations, and its cycle is about eighty years long. Society has seasons too. There is a new beginning in the aftermath of a crisis in Spring, the growth of new institutions and ideas in Summer, overreach and conflict in Autumn, and a new crisis coming to a head in Winter. This is a pattern we see over and over again. If we live a long life, eighty years or more, we will live through each season and return to the season of our birth.

Each generation is born in a particular season, and that shapes how they experience the Great Wheel. For example, a person who is born in Spring enters the world when the crises have been resolved, when people are optimistic about the future, and when life seems safe and stable for most people. Their young adulthood is in Summer, when exciting new ideas can be explored and freedom is the greatest good. The last two Spring-born generations, the Baby Boomers and the Missionary Generation born in the late Victorian period, had this experience.

However, someone who is born in Autumn has a very different experience. They are born when shadows are lengthening, when the world is seeming an increasingly fragmented, combative, and unsafe place. The Crisis era, Winter, hits them in young adulthood, calling on them to be the heroes and rebuilders. The last two Autumn-born generations, the Greatest Generation and the Millennials, had this experience.2

In other words, each person who lives a long life sees all four seasons but at different points in their life, which makes their lived experience extremely different. This chart illustrates this:

|

Generation |

Youth |

Adulthood |

Maturity |

Old Age |

|

Spring-born |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

Winter |

|

Summer-born |

Summer |

Autumn |

Winter |

Spring |

|

Autumn-born |

Autumn |

Winter |

Spring |

Summer |

|

Winter-born |

Winter |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

So who are you? The oldest generation living today is the Greatest Generation, born from 1905 to 1925. This is the generation that fought World War II and built the new, shining Tomorrowland America of the 1950s. They were Autumn-born in the last saeculum. In 2020, the youngest of them are 95 years old.

The next generation, and the first still highly influential in public life in 2020, is the Silent Generation, born from 1926 to 1942. Too young for World War II and too old to be hippies, this is the generation of Nancy Pelosi, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Bernie Sanders. The youngest of this generation are 78 in 2020, and their influence is waning. They are the Winter-born generation born during the last crises, the Great Depression and World War II.

They are followed by the Baby Boomers, born 1943–1960. In 2020 this is the generation that holds the most power, including Donald Trump, Elizabeth Warren, and Chief Justice John Roberts. Spring-born, they came of age in the 1960s and 1970s.

Next comes Generation X, born 1961–1980. Their influence is rising as they enter their most powerful years. Summer-born, they came of age in the darkening years of the 1980s and 1990s. In 2020 the oldest are 59 and the youngest 40.

After them come the Millennials, born 1981 to perhaps 2001. (The dividing line between Millennials and Homelanders isn’t clear yet.) In 2020 they will all have come of age, with the youngest about 19 and the oldest 39, passing the Baby Boomers as the largest voting bloc. Autumn-born, they have always known a darkening world.

Last are the Homelanders, born 2002 or since. They are born in the Winter of this current crisis and are children and teenagers in 2020.

As we reach the climax of this current Crisis era, each generation has a unique role to play. The Silent are the elder statesmen and the seasoned community leaders. The Baby Boomers precipitate the crisis and have leadership roles on all sides. They set the parameters of the conflict. Generation X provides the practical, on-the-ground, day-to-day expertise. They end the conflict. The Millennials fight the conflict. They are the young participants. The Homelanders are mostly too young to be part of the conflict, but they are shaped by it for their dominant role as the wheel turns, in their season of Summer.

The Seasons of the Great Wheel

The Great Wheel, like the Wheel of the Year, is divided into octaves. These are approximately ten years long, the full circle of the wheel being approximately eighty years—the length of a human life. We are all familiar with the basic diagram of the Wheel of the Year as it’s commonly presented in Paganism today:

We travel around the wheel clockwise, experiencing each season in its turn. There is no way to skip a season or to turn the wheel backward and return to a previous season without going all the way around the wheel.

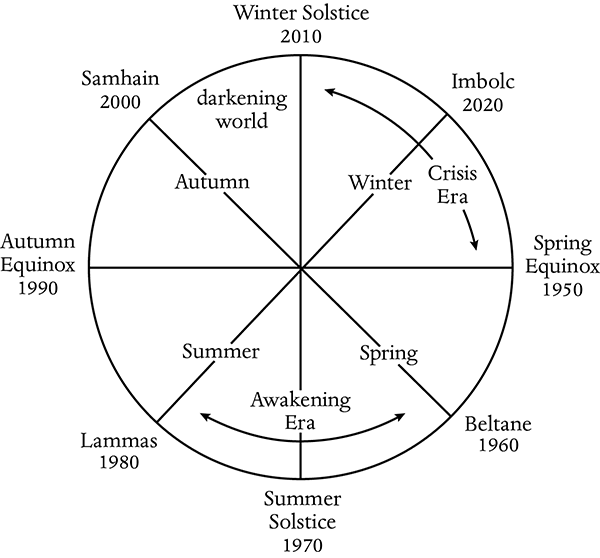

The Great Wheel applies this concept to the Great Wheel of the Saeculum. In Spring, society has big plans and is optimistic and sees enormous growth. In Summer some of those plans come to fruition and others become sources of conflict as ideologies emerge that would lead society in different directions. The apparent consensus of Spring is broken. In Autumn growth slows, creating a dimmer mood as the conflicts become more apparent. In Winter those conflicts erupt into a crisis, often into actual war by the end of the era. There are winners and losers. Conflicts are resolved, conclusions are reached, and the cycle begins again.

If we mapped the seasons of the great year, the diagram of the last eighty years would look like this:

In 1950 we stood at Spring Equinox. World War II was over, the economy was booming, and we stood at the beginning of a long optimistic period in American history, when it seemed like science and law could make tomorrow better than today. Bigger, brighter, faster—there was nothing we couldn’t do!

1960 brought us President Kennedy’s promise to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade, and the sixties were a wild ride from the pastel-Chanel-suit-and-pillbox-hat beginnings to Woodstock and the Vietnam War —the season of Beltane in all its fire.

By 1970 Summer was upon us in earnest, hot and ripe with conflicts that erupted to disrupt the American high and slowly, ever so slowly, begin our turn to the dark of the year. The summer’s longest day is at midsummer. After that we were already descending, though it may not have been apparent.

1980 was our Lammas, the first harvest and a ripe, rich time. Conflicts brewed beneath the surface, but our national institutions seemed strong and our power infallible.

Fall Equinox came in 1990 with riches being reaped by many and those who were left behind being easy to ignore because Yuppies and Babies on Board dominated the national consciousness.

2000 brought us Samhain, a turn to the dark. Seasons don’t always arrive precisely on the date, but Samhain truly began on September 11, 2001. Our national season of Winter had begun.

2010 was our Winter Solstice, when it became clear that we were in the midst of Winter and that storms would surely overtake us soon. Conflicts of all kinds dominated the national discourse.

In 2020 we stand at Imbolc with the worst of this Winter’s storms ahead and Spring still distant beyond the horizon. This is where we are.

Ekpyrosis and Rebirth

Just as each year in the Wheel of the Year experiences winter, so does each cycle of the great year experience saecular Winter. This is, quite simply, a time of crisis. Every eighty years we pass through what the Classical Greeks called ekpyrosis, a destruction by fire that then allows for rebirth and the growth of new things. This is not like the Christian concept of apocalypse, which is about disasters that signify the end of the world. Ekpyrosis is the mechanism by which the world ends and begins anew.

Imagine a volcanic eruption like the eruption of Mount St. Helens in the state of Washington in 1980. Thousands of tons of superheated ash and rock were released, blowing debris into the stratosphere. The shockwave leveled forests. The cloud of ash overwhelmed everyone in its way, including scientists taking pictures of the event, their cameras recovered later to show that they kept filming even as they were overtaken. Nearly sixty people were killed. Fifteen hundred elk and five thousand deer died, as well as twelve million fish and countless smaller animals. The crater left behind was two miles wide, and ash fell from Seattle to Spokane. Photos taken afterward show a complete wasteland, a desert of ash marked with the skeletons of burned trees. It seemed impossible that the beautiful forest could ever return.3

Arriving just a few days after the eruption, ecologist Charlie Crisafulli saw nothing but destruction. He said, “It looked like everything had been destroyed, that all vestiges of life had been snuffed out.” 4 And yet as he investigated, he saw that the high lakes had been protected by ice, their plants and animals still alive beneath the surface. Ants scurried through the ash. Moss survived and spread over downed trees. A gopher emerged from its burrow, having literally ridden out the eruption in its underground bunker.

Within a year, wildflowers bloomed, forests transformed into meadows, birds came to eat the seeds, and pollinators thrived. Alder and willow seedlings began to grow where huge fir trees once had.

Twenty years later, young hardwood trees began to make groves, attracting elk and deer. The streams and lakes once again teemed with fish. Chipmunks, squirrels, and songbirds were plentiful.5

Now, nearly forty years later, the big trees are coming back. There’s a forest again, albeit not yet an old-growth forest, but it has understory plants like lily of the valley and animals like foxes drawn by the plentiful wildlife. Once again the elk thrive. The giant fir trees are saplings coming up through the understory.

This is ekpyrosis. There is disaster and then recovery. The new thing isn’t exactly like the old thing, but new things grow surprisingly quickly. The world ends and then begins. This is as true of societies as it is of forest ecosystems. Just as the natural geologic cycle drives the eruption of volcanoes, the cycle of the saeculum drives the rebirth of human societies.

This is the map of our past and our present. In order to understand how we move forward from here, we need to look back at previous great years. If you want to know what February is like, the best way to know is to examine your experience of previous Februaries. The best way to understand what happens next in the great year is to examine our experience of previous saecula. However, because the cycle of the great year is eighty years long, most of us have not experienced the season we are in before.

However, others have. Other generations that share the same birth position on the Great Wheel as us have stood in the same season. Their experiences can guide us, just as a mariner on unfamiliar seas is guided by the charts and notes of those who sailed this way before. Let’s take a quick look back at how the previous saecula have worked and how each generation’s role has developed. (A much more thorough and complex treatment of each octave of the Great Wheel can be found in my book, The Great Wheel, in which I go deeply into each season of the great year and how it is experienced and expressed by each generation.)

The scholars William Strauss and Neil Howe exhaustively examined these cycles in American history in their book, Generations, which I encourage you to read if you are interested in an in-depth look at the historical cycles. However, to sum up their work briefly, we can see this cycle at work if we simply look at the dates.

In 1945 World War II ended, the end of a Crisis era that had convulsed the world. Eighty years earlier, in 1865, the Civil War ended, concluding another Crisis era. Eighty-two years earlier, the Treaty of Paris of 1783 ended the American Revolution. Strauss and Howe continue back more or less in eighty-year increments. In 1692 the Salem Witch Trials ended a Crisis era that determined whether the American colonies would be a Puritan state or not. In 1588 the Armada Crisis concluded England’s wars with Spain, determining whether the dominant power and culture in North America would be English or Spanish.6 Since the early modern era, these cycles of ekpyrosis and rebirth have been apparent in American life.

Now it’s time for that part of the cycle again. Count eighty years forward from 1945 and you reach 2025. The upheavals we are experiencing are not unnatural or unprecedented. They are a natural part of the cycle of history, of the Great Wheel.

This makes the times we live in no less dangerous! The Spanish Armada, the Salem Witch Trials, the Civil War, World War II—all were critical, dangerous moments that changed the lives of millions. We are deep in Winter, about to pass through the fire of ekpyrosis, with the time of new growth and rebirth still some years away. How do we live in these times?

This book seeks to answer that question, first by examining how our ancestors did it, then by providing positive steps that we can take now and in the next few years, and lastly by helping us create the institutions and circumstances that will allow us to weather the storms and find our way safely to port.

1. deTraci Regula, The Mysteries of Isis (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 1996).

2. William Strauss and Neil Howe, Generations (New York: Morrow and Company, 1991).

3. Robert I. Tilling, Lyn Topinka, and Donald A. Swanson, “Eruptions of Mount Saint Helens: Past, Present, and Future,” United States Geological Survey, 2002, https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/7000010.

4. Charlie Crisafulli, “35 Years after Mount St. Helens Eruption, Nature Returns,” interview by Michael Casey, CBS News, May 18, 2015, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/35-years-after-mt-st-helens-eruption-nature-returns/.

5. Michael Casey, “35 Years after Mount St. Helens Eruption, Nature Returns,” CBS News, May 18, 2015, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/35-years-after-mt-st-helens-eruption-nature-returns/.

6. Strauss and Howe, Generations.