Beyond Borders

Remote Control and the Continuing Legacy of Racism in Immigration Legislation

Don’t you see that the man who comes here selects us, And that is what causes our worry and fuss: Our selection of aliens should begin over sea. And not when they enter this land of the free.

—Terence Powderly, Grand Master of Knights of Labor and Commissioner General of Immigration (1892–1902)

It is much easier to refuse a visa than to deny admittance to the suspected person after he has arrived at a port of entry of the United States.

—Secretary of State Robert Lansing to President Woodrow Wilson, August 20, 1919

Controlling immigration to the United States became effective in the 1920s only when the government learned how to stop migrants before they left their home countries, but the US government tried to develop a system of remote control long before that. Immigration authorities created a system of medical inspections, visas, and passports that turned consular offices and shipping companies into frontlines for immigration enforcement. By the 1920s, these extraterritorial boundaries became the most significant obstacle to entry, more daunting for immigrants than the inspection checkpoints at US ports of entry. These overseas inspections could prevent migrants from departing their home countries and thus control immigration flows far more effectively. That the United States secured this international cooperation reflected its growing influence around the world. These practices were not solely a symbol of US imperial reach, however, but of an expanding global system of border security and migration control. Concerns over national security and the regulation of borders pushed countries to enforce migration laws by what political scientist Aristide Zolberg calls “remote control.”1

Remote control refers to the practices and mechanisms to enforce immigration policy beyond the nation’s borders as well as the efforts to outsource enforcement to private companies. Reliance on private companies has expanded and contracted since the late nineteenth century, but the overall trend has been toward greater direct government control over immigration enforcement. While pushing private companies to enforce immigration laws may be read as a sign of state power, it also reflects the inability of the state to enforce its own regulations. As Adam McKeown shows in Melancholy Order, the US government’s efforts to gain control over the visa and documentation process in China, where it first became a regular practice in the mid-nineteenth century, were continuously undermined by Chinese officials and private entrepreneurs.2 The aim of extraterritorial migration control was to be able to track migrants and to distinguish between citizens, legal residents, and inadmissible aliens before they even boarded ships or trains. Passports and other letters of introduction have a longer history, but until there was a centralized state bureaucracy to standardize these documents, they were not useful for tracking and regulating mobility.3 Remote control through medical inspections and certificates of residency for Chinese were thus the primary mechanisms to regulate movement before the standardization of the passport during World War I. By the time of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, remote-control practices had become institutionalized through consulates that were responsible for sorting and selecting immigrants based on national quotas.

Historians of migration who still see the world through national lenses focus on what happens once migrants reach a port of entry. A transnational perspective that allows us to see the entire migratory circuit reveals that exclusion occurs more often before migrants leave their home countries or in third-countries surrounding the intended destination. The extraterritorial enforcement of immigration restrictions emerged in the nineteenth century as a way for countries to keep undesirable migrants from their shores. From World War I through the 1920s, this system of remote control solidified through the internationalization and regimentation of a regime of passports and visas that has now become standard practice around globe. Although the United States was at the forefront in establishing a robust immigration bureaucracy in the late nineteenth century, it was by no means the only country to erect immigration restrictions. The cooperation of countries in controlling the movement of people was a new way of recognizing the sanctity of national boundaries and national sovereignty. While the United States coaxed other countries to comply with its restrictions, those countries often resisted US demands or had their own reasons for implementing restrictionist policies. The global system of migration restriction put in place in the 1920s emerged out of these earlier efforts. The pre- and post-1920s era of migration restriction are inextricably linked and the two periods cannot and should not be seen as distinct phases in US immigration policy history.

Enlisting private transport companies to enforce migration restrictions was central to the emerging new order. From the nineteenth century through the 1920s, the relationship between private transport companies and governments waxed and waned. Although the early outsourcing of inspections in the 1860s and 1870s reflected the inability of government inspectors to get the job done, by the 1920s, the US immigration bureaucracy was robust enough to conduct its own inspections and demand compliance by private companies. The regularization of travel documents and the professionalization of the Foreign Service in the 1920s helped the United States government to gain control over what previously had been a fairly chaotic system of inspections and haphazard travel permissions. It is not a coincidence that the national-origins quota acts emerged in the 1920s. Without a vigorous remote-control bureaucracy in place, it would have been impossible to sort through millions of immigrants before they arrived on US shores.

Migration and borderlands scholars have explored exclusions at the borderline, but they have paid short shrift to the bureaucratic mechanisms of extraterritorial immigration control.4 The large number of migration books with “fence” or “gate” in the title suggests an emphasis on the physical boundary line.5 While such a focus on gates and borders makes intuitive sense, it has obscured the much more important web of global barriers before migrants even set foot on a particular country’s soil. Aristide Zolberg, Adam McKeown, Elizabeth Sinn, Amy Fairchild, and others have highlighted overseas consulates and medical inspections as a site of migration control.6 It is ultimately these extraterritorial measures that created enforceable borders around the nation and helped to form the global order we know today. The nation-state might imagine itself as a coherent territory demarcated by clear borderlines, but it is actually a web of global economic and political relationships. The more powerful the nation, the more potent are its global tentacles.

The accretion of restrictive immigration legislation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries culminated in the national-origins quotas in the early 1920s. By this point, what had largely been a domestic system of border inspections had become a massive bureaucracy for sifting immigrants in consular offices around the globe. In this era, if an immigrant made it to US shores, they were almost always guaranteed entry. Undocumented entry of migrants from around the globe across land borders with Canada and Mexico continued in spite of restrictionist laws, but the 1924 act managed to make the country whiter by privileging legal entry of northern and western Europeans. The Hart-Celler Act in 1965 ended national-origins quotas and established hemispheric quotas, but rather than an opening, these new quotas represented a slamming shut of the door on Mexicans and Canadians who composed the vast majority of immigrants from the Americas. In 1976, national quotas were reintroduced with a maximum of twenty thousand for each country. The drastic reduction of legal immigration from Mexico—from an annual two hundred thousand braceros and thirty-five thousand regular admissions for permanent residency during the 1960s to just twenty thousand—created a new surge in unauthorized entrants.7 Border enforcement grew throughout the late twentieth century as gaining a visa from particular countries, especially Mexico, became increasingly difficult. The Hart-Celler Act and the 1976 reform created a false appearance of equality by providing each country with the same quota, but given the historically high levels of immigration from particular countries, formal equality created greater de facto restrictions for countries like Mexico. Discrimination continued under a different guise.

Early Remote Control, 1880s–1920

The 1924 nation-based quota restrictions were the culmination of forty years of experimentation with various forms of ethnic and class-based exclusion. The 1880– 1920 period is crucial to understanding how the mechanisms for managing migration developed. Historians have tended to focus on debarment or deportation, looking at Ellis Island and Angel Island and the US-Mexico border as the principle sites of exclusion, but blocking migrants before they were even able to leave international ports was numerically much more significant. Historian Deidre Maloney calculates that deportations averaged just 1 to 3 percent of the total number of immigrants admitted in any given year during the twentieth century. Throughout the twentieth century, removals or “debarment” before a migrant had officially entered the country far outpaced deportations.8 However, accounting for both deportations and removals still hides an important element in the selection process—that is, prospective migrants denied visas by consuls or prevented from traveling by steamship lines for medical or other reasons. These rejections do not show up in the Bureau of Immigration data. Historian Amy Fairchild calculates that the rejection rate in overseas consulates averaged 5 percent between 1926 and 1930, which she notes was 400 percent greater than the average number of rejections at US ports from 1891 to 1930.9 Evidence from the US consulate in Hong Kong suggests that it preemptively rejected half of all prospective migrants at the beginning of the twentieth century. Although precise numbers are hard to come by for every port of embarkation, it is clear that far more migrants were rejected abroad than in the United States.

Early efforts at remote control were largely ineffective because government officials were not that zealous in enforcing migratory restrictions. Since the midnineteenth century when Europeans began to transport large numbers of Asian contract laborers to plantations around the world, consuls acted as labor recruiters and regulators. These dual functions often caused a conflict of interest. After 1862, for example, US consuls in Hong Kong were charged with assuring that all Chinese departing on US ships were leaving voluntarily, but, beginning in 1875, they also became responsible for enforcing the provisions of the Page Act that banned the immigration of prostitutes and Asian contract laborers. After the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, consular officials in Hong Kong were responsible for issuing the Section 6 certificates that exempted students, merchants and diplomats from restriction. When David Bailey became US Consul in Hong Kong in 1871, he criticized his predecessors’ efforts to prevent American involvement in the coolie trade as a “complete farce.” Eight years later Bailey was accused by his successor of being more interested in collecting fees than enforcing the regulations.10 Remote control was not very effective when consular officers took little interest or had a financial stake in the trade they were supposed to be regulating.

Although the US consuls were ineffective or disinterested in the 1860s and 1870s, by the 1890s, the Immigration Bureau relied on them because they ostensibly had the local knowledge to be able to detect fraud better than immigration officers at US ports. Consul Rounsevelle Wildman in Hong Kong, for example, charged that some of the bureau’s telltale signs to distinguish coolies from merchants made no sense in China. He explained that he checked applicants for the “marks of the coolie,” namely calluses on the shoulder and shabby clothes, to detect fraud. In 1898, Consul Wildman proudly noted that he rejected more than half of visa applicants based on his investigations.11 If Wildman’s statement can be believed, getting past the consul in Hong Kong was roughly twice as hard as getting by immigration inspections at US ports, which averaged a 28 percent rejection rate for Chinese.12 Recriminations between US consuls and the Chinese government over lax regulations of visas finally led to complex procedures in 1896 that required an applicant for emigration to pass through investigations by a local superintendent of customs and then a local viceroy in China before proceeding to a US consul for a visa.13 In her study of Hong Kong as a hub of Pacific migration, Elizabeth Sinn shows how the British had similar problems enforcing their anti-coolie trade measures until they enlisted the Chinese board of directors of the Tung Wah Hospital in the early 1870s to root out corruption.14 The reliance of the British on Chinese merchants to help curb trafficking abuses suggests that they needed local help to enforce their own regulations. Between the 1870s and late 1890s, British and US enforcement of migration controls in China became more effective through the cooperation of the Chinese government and local merchants. Remote control was most effective when foreign governments, local merchants, and transport companies were all working together to enforce migration restrictions. After 1924, it was not only Chinese laborers, those likely to become public charges (in other words, the poor), and those with contagious diseases who had to be screened; every immigrant was vetted. The 1924 restrictions shifted the regulatory bureaucracy into overdrive as millions of prospective immigrants had to be sifted and sorted in consular offices around the globe.

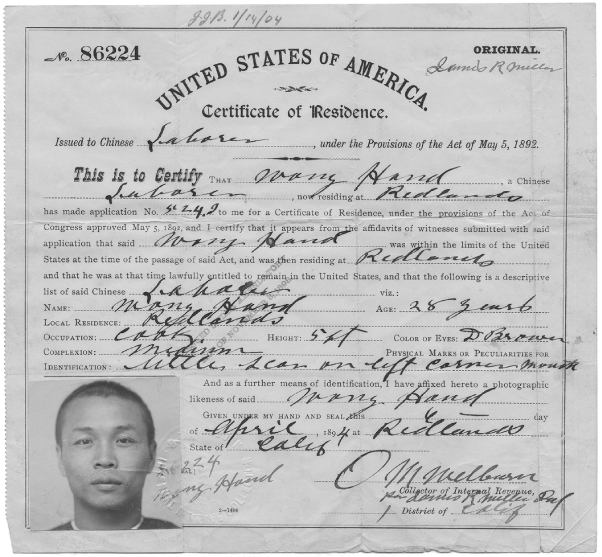

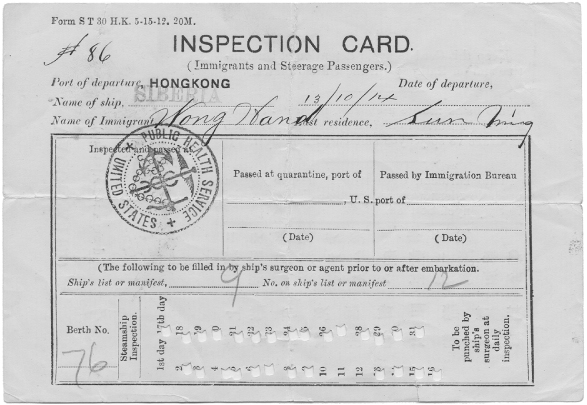

Beyond consular evaluations, the most important method of controlling migration and the first line of defense against unwanted immigrants was the US Public Health Service’s (PHS) overseas inspections. Medical examiners from the United States were stationed in ports in Japan and China as well as in Canada, Cuba, Western Europe, and Russia; their job was to prevent potential immigrants with diseases from boarding vessels headed to the United States. After the federal Quarantine Law of 1893 and a series of agreements with officials in Naples, Italy, and then China and Japan in 1903, PHS officers began inspecting prospective emigrants in foreign ports. Although the US officials did not technically have the power to prevent departure from these ports, they passed lists of diseased immigrants to the steamship companies, who usually rejected them. It was in the interest of the steamship companies to take the PHS officers’ recommendations because the company could be fined $100 for each returned migrant.15 The 1903 Immigration Act solidified this practice, requiring medical examinations abroad before prospective migrants embarked on their journey. For example, in 1914, even though Wong Hand had a certificate of residency dating to 1894 and passed an inspection by a US public health office in Hong Kong, he still underwent thirty-one medical inspections by the ship’s surgeon on the Pacific Mail steamer Siberia while en route to San Francisco (see figures 1 and 2). Without this certificate Wong would have been placed in quarantine upon arrival in San Francisco.16 In 1914 the Surgeon General announced that in Boston authorities noted a marked decrease in the number of immigrants with communicable diseases despite an increase in immigration. He attributed this decrease to the “more careful examination made at the foreign ports of embarkation in order to avoid fines and deportations.”17 Medical inspection abroad was working. After 1924, although there were fixed quantitative quotas for each country (except for the Western Hemisphere and the so-called Asiatic Barred Zone), the qualitative diagnoses of contagious diseases continued to be a major barrier for certain ethnic groups. Although medical diagnoses were supposed to be based in objective science, medical inspectors had racist notions of which bodies would be prone to carry particular diseases.

Medical inspections, like the entire immigration process, were based on racist preferences for white Europeans. PHS officers rejected Asians at much higher rates than they did Europeans, reaching a rejection rate as high as 65 percent in China and Japan compared with only 4 to 6 percent in Naples, Italy.18 The overall rejection rate at US ports from 1908 to 1932 for non-Chinese was only 3 percent, compared with 28 percent for the Chinese.19 Europeans mainly entered through Ellis Island (1892), where only 1 percent were rejected, compared with 18 percent rejection rate at Angel Island, where most Chinese and Japanese arrived.20 The disproportionate rejection of Asians versus Europeans reflects the racism of consular officials and immigration inspectors as well as the racism embedded in immigration laws. Thus, while all consular rejections were greater than those at ports of entry, this differential was even greater for Asians. The point is that if you could manage to make it to U.S soil and were not Asian, you had a fairly good chance of getting through the gate because the main selection process had already taken place in a foreign country. The supposed objectivity of medical exclusions that were perfected in the 1910s and 1920s foreshadowed the apparently nonracialized objective criteria for admission after 1965. In both cases, the outcomes disproportionately targeted nonwhite immigrants.

Figure 1. Wong Hand’s certificate of residence showing that he was a resident of Redlands at the time the 1892 Act, requiring Chinese to carry such identification, was passed. Courtesy of the Asian American Studies Collections, Ethnic Studies Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Figure 2. Wong Hand’s 1914 inspection card indicating that he passed thirty-one medical exams on the voyage from Hong Kong to San Francisco. Courtesy of the Asian American Studies Collections, Ethnic Studies Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In the nineteenth century the bureaucracy for medically inspecting and certifying prospective migrants and determining their eligibility for entry lacked standardization and coherence. The government relied on shipping companies to enforce regulations, making them financially and even criminally liable for bringing in undesirable or unlawful immigrants. As early as the 1837 revision of the alien passenger law, shipping companies were required to post $1,000 bonds for “lunatic, idiot, maimed, aged or infirm” immigrants and to pay a $2 tax to help the state’s efforts to maintain paupers.21 The 1882 Immigration Act levied a fifty-cent tax on all alien passengers for the maintenance and support of the regulatory system, and required shipping companies to assume the transportation costs for any immigrant not permitted to land.22 The 1891 Immigration Act also levied a fine of up to $1,000 and up to a year in prison for smuggling illegal passengers. For all passengers who were found to have arrived unlawfully, with or without the shipping companies’ knowledge, the shipper was fined $300 per immigrant.23 The 1907 Immigration Act also saddled these companies with the cost of return as well as half of the total deportation costs if immigrants became public charges due to preexisting conditions within three years of their arrival.24 By making the shipping companies financially responsible in these ways, the government shifted liability for deportations to private companies. The 1907 Act therefore culminated what had been a slowly evolving shifting of responsibility to private companies for determining eligibility for entry to the United States by assessing the legitimacy of entry documents, performing medical exams, and screening for the long list of excludable categories.25 However, unlike in the 1870s in Hong Kong when the United States relied on steamship companies to enforce migratory regulations because the immigration bureaucracy was undeveloped, by the twentieth century, the US Immigration Bureau outsourced its inspections from a position of relative strength.

This power struggle between the state and private shipping companies played out in Europe in the first decade of the twentieth century as consular officers increasingly exercised their muscle. Fiorello La Guardia, who would later become mayor of New York City, was at the center of that struggle as a young consular agent in Fiume, Hungary (now Rijeka, Croatia). La Guardia arrived in Fiume in 1903 just as a steamship line began offering transportation to New York. Although he was required to certify the health of all passengers and that the ship was free from contagious diseases, there were no specific instructions on how to carry out such inspections. La Guardia decided to hire local physicians to conduct medical exams, a move which ran afoul of the steamship line’s managers, who counted on less rigorous exams. La Guardia retaliated by refusing to issue his certificates of health, a decision that would have resulted in stiff fines once the ship arrived in New York. In the end, the steamship company was forced to accept La Guardia’s inspections and to pay for them.26 La Guardia’s ad hoc diplomacy in Fiume shows not only how the US government was able to extend its legal reach to foreign ports, but also how it made private companies partners in the execution of US immigration policies in the early twentieth century.

Facing the same kinds of pressures at the beginning of the twentieth century, German steamship lines erected elaborate inspection stations in port cities, and the Prussian railways inspected emigrants before they even arrived at the coast.27 In a 1902 investigation of the Hamburg inspection facilities, a US official concluded, “It is entirely clear, although the numbers rejected in America may be small, that this is entirely due to the elaborate precautions which are taken before the emigrants start to prevent the possibility of their rejection.”28 The US Immigration Commission of 1907 discovered that the pre-inspection procedures established by the French, Swiss, Hungarians, and Germans were more effective in preventing unauthorized migrants from boarding ships than were US public health inspectors stationed throughout Europe. Their effectiveness can be attributed to their increased financial interest in not shipping diseased migrants. Once European shippers took responsibility for pre-inspections, they could also more easily be held responsible for returning rejected migrants. Given the effectiveness of private companies in enforcing US immigration laws, the US government preferred out-sourcing preemptive inspections and therefore recalled US public health officers from Japan, Hong Kong, and the Russian port of Libau in 1909.29 However, the privatization of the inspection process required a state strong enough to ensure that the private corporations would take seriously the tasks they were assigned. Privatization, in this instance, was a reflection of growing state power.

The overlapping jurisdiction of private companies and state officials led to disagreements in some cases, especially when steamship companies enforced regulations even more strictly than consular officials. In determining which passengers required medical screening, steamship companies first had to determine whether potential passengers were US citizens or aliens. The transport companies accepted only two forms of proof of citizenship, a passport or court documents indicating citizenship.30 However, before World War I, passports were not in general use, and therefore many US citizens traveled without such documentation. It wasn’t until 1914 that the State Department announced that all US citizens “should” have a passport when traveling abroad. A year later President Wilson issued an executive order indicating that passports were a necessity for those traveling to Europe.31 In 1908 the US consul in Hong Kong, Amos Waldir, complained about the rigidity of steamship companies that resulted in weeks’ delay for a Chinese family with US citizenship who were unable to board a ship because their infant child was placed on the “alien list” and then diagnosed with a trace of trachoma. The consul believed that the family would have been able to prove their citizenship and that of their child to immigration authorities in a US port, but the strict rules in Hong Kong made such verification impossible. Recognizing these difficulties, the consul asked that US authorities affirm his power to make an initial determination of US citizenship. Denying the right to prove their citizenship in a US court was, the consul protested, an “unworthy limitation of American citizenship.”32

In another case, a US-born citizen of Chinese descent was abandoned by her husband in China when he ran off with a second wife. The husband took the passport that listed his wife and their fourteen-year-old daughter as US citizens, both born in the United States. In spite of having the husband’s court papers and other proof of citizenship, they were not able to return to Seattle because the steamship company would not accept their documents. The consul was outraged that this “poor woman” and her daughter, “a cultured product of American school and church,” would be denied their rights as American citizens to return to their country of birth, or even be given the opportunity in Seattle to prove their citizenship status.33 The consul’s emphasis on the family’s Americanization indicated how important cultural assimilation was to claim the benefits of US citizenship. The case also shows the kinds of tensions that emerged between private companies and state officials before the regularization of passports and visas.

These cases reported by the consul in Hong Kong highlighted the immense power that had been placed in the hands of often young and inexperienced medical doctors and low-level steamship employees stationed in foreign ports. The consul was incredulous: “I cannot believe the humane men at the seat of government realize what suffering is caused, what rankling sense of injustice is kindled among the Chinese by gradual growth of the trachoma test, … [in which] an inflammation of the inner eyelid is the heart of the momentous Chinese immigration question.” At the end of his lengthy letter, he called for further investigation of trachoma to consider “not merely the physiological but the humane and political factors that enter in.”34 However, this was not merely a question of physiology versus politics. The physiological diagnosis of the disease itself was a political question, one that had a different answer in Hong Kong, Vancouver, and San Francisco and depended on which doctor one consulted in each of those places. The steamship companies often enforced US restrictions with more zeal than US officers because the companies were responsible for returning inadmissible aliens. For the steamship companies, it was an economic more than a humanitarian question.

It was not only the steamship companies, however, that were motivated by economic consideration. The Bureau of Immigration proved adept at relaxing medical standards when employers demanded more labor. When Chinese were prevented from returning to the Philippines, then an American territory, because of their high rates of trachoma, the bureau simply encouraged a “more lenient criteria to diagnose trachoma.”35 The need for Chinese labor in the Philippines trumped the fear that migrants would bring in contagious diseases. It is telling that such lenient criteria were never recommended for passengers bound for the United States. The constant disputes between transport companies, immigration officers, medical inspectors, and consuls encouraged the development of an ostensibly more objective quota system with clearer lines of authority for determining entry eligibility. The 1924 Immigration Act did not eliminate the discretion of border guards, but the onus for determining immigrant admissibility shifted to consuls and a bureaucratic visa requirement.

Consolidating Remote Control: The First World War to the 1920s

A more robust system of inspection developed as a result of fears of enemy infiltration during World War I. On July 26, 1917, a joint order by the US Departments of State and Labor established for the first time a visa requirement for entry to the United States. The next year, the Passport Control Act established executive authority over the entry and exit to the United States by both citizens and foreigners. As Secretary of State Robert Lansing advised President Wilson in 1919, “It is much easier to refuse a visa than to deny admittance to the suspected person after he has arrived at a port of entry of the United States.”36 The result of the new passport, visa, and consular inspection requirements meant that the overwhelming majority of immigrants who arrived in the United States would be admitted based on the documents they carried rather than a bodily inspection.

In 1924, the same year Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, the Rogers Act created the Foreign Service, professionalizing consular posts, establishing a merit-based system for employment, and giving consular officials the task of conducting immigrant inspections. The professionalization of the Foreign Service gave the government more control over its consular officials. It also helped to create more uniform standards to assess citizenship and avoid the kind of conflicts that had emerged earlier in Hong Kong. By 1925, the PHS inspection line at Ellis Island was ended and instead immigrants were given cursory examinations aboard ships to ensure they had proper visas and clean bills of health.37 By 1930, only 5 percent of immigrants arriving in New York were sent to Ellis Island, usually because they were suspected of becoming public charges. The new system of screening immigrants before their arrival was working more efficiently and effectively than ever before. In the first four years of enforcement of the 1924 quota restrictions, only .02 percent of those immigrants arriving with visas were rejected.38 In 1927 the Immigration Service’s Second Assistant Secretary W. W. Husband wrote to the surgeon general, exclaiming that the inspection of immigrants abroad has “proven successful beyond any of our fondest dreams.”39 Although transport companies were still responsible for returning rejected aliens, determining eligibility for entry was increasingly the domain of an expanded US immigration and foreign service bureaucracy.

The ability to control migration into and out of its territory was not only the mark of a modern nation, but it also reflected their global influence in garnering the cooperation of other countries. As historian Donna Gabaccia shows in her book Foreign Relations, migration control was not simply a “domestic matter.”40 Although the United States attempted to pressure other countries to help enforce its restrictive immigration policies, those countries often resisted or passed restrictive legislation for their own domestic reasons. Military interventions gave the United States more leverage over these other countries’ migration policies, but they also had the unintended consequence of creating new migratory streams. In US-occupied Cuba, for example, the US military replicated the Chinese Exclusion Act on the island in 1902 by decree, inhibiting Chinese migration to Cuba (see chapter 2 in this volume). In contrast, the US takeover of the Philippines turned Filipinos into US nationals, which facilitated their migration to the United States by exempting them from the restrictions placed on all other Asians. The 1934 Tydings-McDuffie Act, which paved the way for Philippine independence in 1946, changed the Filipinos’ status for the purpose of immigration and gave them an annual quota of fifty.41

Canada, Cuba, and Mexico represent three different levels of cooperation with the United States regarding Chinese exclusion. Cuba was the most compliant, replicating the US ban on Chinese labor in 1902. Canada cooperated with the American law early on and eventually imposed its own Chinese labor exclusion in 1923. Mexico resisted these policies the most, at least in the late nineteenth century; but by the 1920s Mexico instituted its own form of nationalist immigration restrictions. Although there were varying degrees of willingness to accede to US wishes, by the 1920s the United States garnered hemispheric cooperation to keep Asians out. It would be a mistake, however, only to credit US hegemony with the development of neighboring countries’ immigration policies. Xenophobic movements in Canada, Mexico, and Cuba pressured governments to restrict Asian migration, but in spite of this racial antipathy, business interests often succeeded in keeping the doors open, at least partially and temporarily. In Cuba, for example, plantation owners, many of whom were US citizens, succeeded in securing Chinese workers in 1917 to work in the sugar cane fields.42 The lack of control over the immigration policies of neighboring countries made it difficult for the United States to prevent clandestine entry. After 1924 these clandestine entries through the so-called back doors became a greater concern as thousands of excluded southern and eastern Europeans began using Cuba, Mexico, and Canada as springboards for illegal entry to the United States.

Asian migrants seeking to avoid the draconian American medical inspections took advantage of laxer policies in neighboring countries to gain access to the United States. The different enforcement of medical exclusion in Canada provides a good example. According to Special Immigration Inspector Braun, US medical examiners in Hong Kong rejected 10 to 60 percent of Chinese and Japanese immigrants, whereas Canadian lines rejected a far lower percentage, and they even allowed ill passengers to sail. The result of this discrepancy led many Chinese and Japanese to seek passage on Canadian ships. Braun worried that the lack of vigilance by the Canadian shipping authorities in Hong Kong might allow diseased passengers traveling in steerage to infect healthy passengers.43 Furthermore, Canadian officials handled the arrival of sick passengers differently than American authorities. Migrants who were found to have a disease upon arrival in a US port were immediately deported, “there being no redress and no opportunity to be treated or cured.” Passengers with diseases arriving at Canadian ports, however, were given medical treatment until cured, at which point, Braun stated, the immigrant was “‘railroaded past the Department medical examiner’ and enter[ed] the United States to become a menace to its citizens.”44 Even though the Canadian government allowed US medical examiners to inspect immigrants bound for the United States, this was not sufficient, according to Braun, because the Canadian medical examiner inspected and treated immigrants before the American examiner had a chance to determine their admissibility.45 The differential treatment in neighboring countries often limited the effectiveness of remote-control procedures.

The medical exams themselves were also subject to interpretation, leading to vastly different rates of rejections in Hong Kong, United States, and Canadian ports. The US consul in Hong Kong provided data on trachoma rejections on six British and American ships that had recently sailed to show how much easier it was for Chinese to enter Canada than the United States. Consul Waldir reported that migrants who entered through Vancouver and were tested for trachoma were rejected at a rate of less than 3 percent, whereas 30 percent of passengers heading to San Francisco were rejected in Hong Kong before they could even depart.46 Given these odds, it is not hard to understand why Chinese or Japanese preferred traveling through Canada rather than directly to a US port. Furthermore, the 30 percent rejection rate in Hong Kong was almost double the rejection rate at Angel Island, making it twice as difficult a barrier to overcome in the exclusion apparatus.47 By the early twentieth century, therefore, most Asians were excluded from the United States while still in Asia. Remote control was not ancillary to immigration restriction; it was the main mechanism for exclusion.

Centralizing and Extending Remote Control, 1924–1965

Remote control mechanisms had been slowly developing since the 1880s, and they accelerated during the First World War, but the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act represented the solidification of these practices as the primary means of immigration control. By the 1920s, inspections and visa denials became the principal mechanism for exclusion, but after 1924 this process became institutionalized, and the Department of State officially assumed the role of gatekeeper. The 1921 Quota Act created chaos. Immigrants were counted as they arrived at ports of entry, which encouraged steamship operators to race to port to land their passengers before quota limits had been reached. In the debate over the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, members of Congress argued that the system of enforcing quota at ports was unwieldy and brought “hardships.” Instead, Congress enacted a new system for “enforcement of the numerical limitation not by counting immigrants upon their arrival, but by counting ‘immigration certificates’ issuable at American consulates overseas.”48 Furthermore, the 1924 immigration act gave consular officials the power to deny visas that was almost absolute. The Secretary of State or the Attorney General could overturn a consular officer decision, but the decision could not be appealed by an applicant or reviewed by the courts.49 Consular officers had more unchecked power than any other US official, including the president, whose decisions were ultimately reviewable by the Supreme Court.

The remote-control system that emerged in the 1924–1965 period used immigration regulations to further US objectives. During World War II, for example, the United States pressured thirteen Latin American countries to arrest 4,085 Germans, 2,264 Japanese, and 288 Italians who were suspected of being “enemy aliens.”50 Some of the supposed “enemy aliens” were naturalized citizens of the Latin American countries where they resided and were suspects simply because of their ancestry. There are even cases of German and Italian Jews who had escaped concentration camps being interned in alien enemy camps in Panama and the United States.51 With the collaboration of these Latin American countries, principally Peru and Panama, thousands of civilians were rounded up and shipped to detention camps in Texas, New York, and other locations around the country. These preemptive detentions were part of a secret plan to exchange US prisoners of war for Japanese, Germans, and Italians. The internees were not technically prisoners of war, but they were held in detention centers run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service after being declared “illegal aliens.” Even though they were forcibly taken from Latin America and had their passports seized, the US authorities declared their entry unauthorized. During and after the war many were repatriated to Japan and Europe.52 This most extreme form of remote control in which the US government apprehended foreign citizens in other countries, incarcerated them in US camps, and then deported them as part of a prisoner exchange program shows the extent to which the United States used civilian detention and deportation as a tool of war. Remote control that began as an effort to police the borders of the nation had become by the mid-twentieth century a projection of US military might around the globe.

A Century of Remote Control

The mechanisms of remote control that were established in the early twentieth century and reinforced during the 1924–1965 period have only grown stronger in the ensuing century. In recent years, the United States has detained and tortured enemy aliens beyond the territorial limits of the nation. Since 2001 the Central Intelligence Agency’s “extraordinary rendition” program and Guantanamo Bay’s prison camp in Cuba demonstrate how the United States extends its military strength through remote control.53 By 2016, US immigration officers were posted in fifteen locations in six foreign countries (Canada, Ireland, the United Arab Emirates, Bermuda, Aruba, and the Bahamas) to prescreen passengers headed to the United States. These preclearance procedures covered more than 15 percent of travelers to the United States; the government wants to expand the program by 2024 to cover 33 percent of inbound passengers.54

The 1965 Hart-Celler Act ended discriminatory national-origins quotas, but discriminatory visa-issuing practices continued, although more hidden from the public eye. In an immigration bureaucracy obsessed with data collection, the fact that there are no easily accessible data that reveal the rejection rate for immigrant visas by country points to one of the ways discrimination remains invisible. In 2013, consular officials initially rejected more than half of the immigrant visa applications (close to 290,000 out of a total of 473,000 applications that were approved). In most of those cases, applicants rectified the causes for denial and their visas were eventually approved, leaving about 95,000 rejections for the year. The final rejection rate was therefore about 17 percent.55 In that same year, 204,000 aliens arriving at land, sea, and air ports of entry were deemed inadmissible.56 Thus almost a third of immigrant exclusions occurred in consular offices and not at the borders. The rejection rates for nonimmigrant tourist and business visas in 2015 show a huge variation by country, with some countries having no rejections (Andorra and Lichtenstein) and others having 85 percent of applications rejected (Federated States of Micronesia).57 Although there are many factors that may be considered in approving a tourist visa, these wildly different outcomes suggest that visitors from some countries are more welcome in the United States than others. And these data do not even account for those who visit from countries in the Visa Waiver Program for whom no visa is even required, including Austria, France, Germany, and Switzerland. People entering under the Visa Waiver Program composed nineteen million or 40 percent of overseas visitors in 2013.58

Today, consulates continue to be the frontlines of immigration control, issuing more than 530,000 immigrant visas along with almost eleven million nonimmigrant visas in 2015.59 Under Trump, visa denials appear to have increased, but the nonreviewability by courts of individual visa decisions is not a new development.60 In 2015 the Supreme Court reaffirmed in Kerry v. Din the absolute right of consular officers to deny visas, even to a spouse of an American citizen, without needing to provide evidence to back up their reasoning. As Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia put it bluntly, “There is no due process to her [the spouse] under the Constitution.”61 Although the new visa quotas may have eliminated the overtly racist national-origins quotas from the 1920s, the visa process continues discrimination through a series of decisions by consular officials that are not subject to appeal or judicial review and that are at the heart of a system of remote control that the United States has built over a century.

Another way in which the equal treatment of countries for visa slots results in disproportionate restriction on particular countries can be seen by analyzing immigrant visa wait lists generated by applicants at consular posts. The family-sponsored visa quota for 2016 was 226,000, and 140,000 for employer-sponsored visas, but each country is limited to fewer than 26,000 visas per year. For Mexico, with over 1.3 million people on the wait list, it would take fifty-two years to clear the backlog, assuming no new applicants registered. The top fifteen countries with the largest waitlists are all in Latin America and Asia.62 Given the impossibility of garnering a visa in a reasonable amount of time, millions of Mexicans and others were forced to enter illegally or overstay their visas. And many of them end up incarcerated and deported. These developments build on a long history of remote control and discrimination that the US government created at the end of the nineteenth century and consolidated during the 1924–1965 period.

Remote-control efforts at consular posts around the world erect formidable walls to legal entry, walls that are much higher for Mexico than, say, for England. When remote-control efforts fail to keep unwanted migrants out, immigration authorities deploy a punitive detention and deportation system that targets black and brown men. Although on the face of it our immigration quotas stopped favoring white northern Europeans in 1965, we can see the same Johnson-Reed Act de facto discrimination occurring today in terms of immigration enforcement. In recent years, just four countries accounted for more than 90 percent of detentions and removals: Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.63 The 1965 immigration act did not end racist immigration restrictions; it merely shifted them onto the terrain of visa application lines and immigration enforcement practices. President Donald Trump’s proposal, when he was the Republican presidential nominee, to ban all Muslim immigrants and his insinuation that Mexican immigrants are “rapists” and criminals suggests that outright racist immigration legislation is a real political possibility in our day. Although district courts on both coasts have declared Trump’s blanket ban on six Muslim-majority countries unconstitutional, a narrower ban has passed Supreme Court muster.64 The faces of the half a million immigrants in detention graphically demonstrate that racism continues in the Hart-Celler era. These incarcerated migrants are the ones who slipped through in spite of remote control. What we do not see are the millions of other potential migrants who remain trapped in their countries or in refugee camps around the world because of the effectiveness of remote control. If we could see these people, the racism of our immigration system would become crystal clear.

Notes

1. Aristide R. Zolberg, A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (New York: Harvard University Press, 2006), 9.

2. Adam McKeown, Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), ch. 8.

3. There is a rich literature on the history of the passport that describes this simultaneous development of a global order and national migration control. See, particularly, John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000); see also Craig Robertson, The Passport in America: The History of a Document (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

4. Two great volumes on US-Mexico and US-Canadian borderlands history that do not deal with extraterritorial enforcement of borders are: Samuel Truett and Elliott Young, eds. Continental Crossroads: Remapping the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands History (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2004), and Benjamin H. Johnson and Andrew R Graybill, eds. Bridging National Borders: Transnational and Comparative Histories (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2010). For a history of Chinese exclusion in Canada, see Lisa Rose Mar, Brokering Belonging: Chinese in Canada’s Exclusion Era, 1885–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010). For a history of Chinese exclusion in Mexico, see Roberto Chao Romero, The Chinese in Mexico, 1882–1940 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2010). Two excellent histories of US immigration restrictions that focus on the US borders over global barriers are Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004) and Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

5. Libby Garland, After They Closed the Gates: Jewish Illegal Immigration to the United States, 1921–1965 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2014); Lee, At America’s Gates; Claire Fox, The Fence and the River: Culture and Politics of the U.S.-Mexico Border (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999); Andrew Gyory, Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

6. McKeown, Melancholy Order; Elizabeth Sinn, Pacific Crossing: California Gold, Chinese Migration and the Making of Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013); and Zolberg, A Nation by Design.

7. Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 261.

8. Deirde M. Maloney, National Insecurities: Immigrants and U.S. Deportation Policy Since 1882 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 8–9.

9. Amy L. Fairchild, Science at the Borders: Immigrant Medical Inspection and the Shaping of the Modern Industrial Labor Force (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 261.

10. Sinn, Pacific Crossing, 241–43.

11. McKeown, Melancholy Order, 218, 224–28.

12. Lee, At America’s Gates, 141.

13. McKeown, Melancholy Order, 226–27.

14. Sinn, Pacific Crossing, 243–48.

15. Fairchild, Science at the Borders, 58.

16. Zolberg, A Nation by Design, 229.

17. Rupert Blue, Annual Report of the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service for 1914 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1915), 203.

18. Fairchild, Science at the Borders, 59.

19. Lee, At America’s Gates, 141. The rejection rate for South Asians reached over 54 percent between 1911 and 1915. Erika Lee and Judy Yung, Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 158.

20. Roger Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882, 1st ed. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 25.

21. Kunal M. Parker, “State, Citizenship, and Territory: The Legal Construction of Immigrants in Antebellum Massachusetts,” Law and History Review 19, no. 3 (2001): 610.

22. US Congress, “1882 Immigration Act, 47th Congress Sess. I, Chap. 376 Stat. 214,” (Washington, DC: GPO, 1882), 214–15.

23. US Congress, “1891 Immigration Act, 51st Congress, Sess. II Chap. 551; 26 Stat. 1084,” (Washington, DC: GPO, 1891), 1084–85.

24. Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door, 43–45; Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization, Department of Commerce and Labor, Immigration Laws and Regulations of 1907 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1910); US House, “An Act to Regulate Immigration,” ed. 1st Session 47th Congress (Washington, DC: GPO, 1882), 214–215; US House, “An Act to Regulate Immigration.”

25. Department of Commerce and Labor, Immigration Laws and Regulations of 1907, 5.

26. Fairchild, Science at the Borders, 60–61.

27. Ibid., 61.

28. McKeown, Melancholy Order, 112–13.

29. Ibid., 113.

30. Amos P. Waldir, American Consulate-General, Hong Kong, to Asst. Sec. of State, July 24, 1908, NARA, RG 85, entry 9, 51881/85, box 275, p. 1–2.

31. Torpey, Invention of the Passport, 117–18. Robertson, Passport in America, 186.

32. Waldir to Asst. Sec of State, July 24, 1908, 3–4.

33. Ibid., 8–9.

34. Ibid., 9–10.

35. E. Carleton Baker, Vice Consul, Amoy, to W. W. Rockhill, American Minister, Peking, April 30, 1908, NARA, RG 85, entry 9, 51881/85, box 275.

36. Robert Lansing, Secretary of State, to President Woodrow Wilson, August 20, 1919, in Woodrow Wilson, “Continuance of the Passport-Control System,” (Washington, DC: Government Printing House, 1919), 3–4.

37. Fairchild, Science at the Borders, 258, 272.

38. Robertson, Passport in America, 187, 205.

39. Fairchild, Science at the Borders, 258.

40. Donna R. Gabaccia, Foreign Relations: American Immigration in Global Perspective (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2012), 50, 13.

41. Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 101.

42. Young, Alien Nation, ch. 6.

43. Digest and Comment upon Report of Immigrant Inspector Marcus Braun, October 9, 1907, NARA, RG 85, entry 9, 51630/44F, box 115, p. 29.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid., 17.

46. Trachoma, an infection of the eye that can cause blindness if not treated, was found primarily in poor communities with an inadequate water supply. The statistics that Consul Waldir lists yields an average rejection rate of 27 percent for six ships sailing May–July 1908, with some ships rejecting as many as 43 percent and others as few as 15 percent. Waldir to Asst. Sec of State, July 24, 1908, 6–7.

47. Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door, 25. Fairchild, Science at the Borders, 59–60.

48. House Report No. 350 accompanying H.R. 7995, 68th Congress, as cited in Abba P. Schwartz, “The Role of the State Department in the Administration and Enforcement of the New Immigration Law,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 367 (1966): 96.

49. Ibid., 98.

50. Jan Jarboe Russell, The Train to Crystal City: FDR’s Secret Prisoner Exchange Program and America’s Only Family Internment Camp during World War II (New York: Scribners, 2015), xix.

51. Russell W. Estlack, Shattered Lives, Shattered Dreams: The Disrupted Lives of Families in America’s Internment Camps (Springville, Utah: Bonneville, 2011), 83, 162. Memorandum, British Legation, Panama City, February 10, 1942, National Archives Record Administration (NARA), RG 389, A1466J, box 13, Paolo Ottolenghi, 2–3.

52. C. Harvey Gardiner, Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981), ch. 8.

53. Monica Hakimi, “The Council of Europe Addresses CIA Rendition and Detention Program,” American Journal of International Law 101, no. 2 (2007); A. Naomi Paik, Rightlessness: Testimony and Redress in U.S. Prison Camps since WWII (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

54. US Customs and Border Protection, “Preclearance Expansion: FY2016 Guidance for Prospective Applicants,” https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2016-May/FY16_Preclearance_Guidance_Feb2016_05%2016%2016_final_0.pdf.

55. This rejection rate was calculated by combining two different data sets. The USCIS data lists all immigrant visas issued by foreign posts, and the Department of State’s Visa Office indicates the total number of applications that were rejected and the rejections that were overcome. US Department of State, “Table 1: Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Visas Issued at Foreign Service Posts Fiscal Years 2011–2015,” https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/AnnualReports/FY2015AnnualReport/FY15AnnualReport-TableI.pdf; see also US Department of State, “Report of the Visa Office 2013,” (2013).

56. Office of Immigration Statistics, “Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2013,” Department of Homeland Security, 2014, table 3.

57. US Department of State, “Adjusted Refusal Rate—B-Visas Only by Nationality, Fiscal Year 2015,” https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/Non-Immigrant-Statistics/RefusalRates/FY15.pdf. The “adjusted” refusal rates undercount actual rejections because only the final determination within a calendar year is counted. A person may be rejected twice and gain admission on a third application, but these data will only count the final determination.

58. Lisa Seghetti, “Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of Entry” (Congressional Research Service, 2015), 9.

59. State, “Table 1: Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Visas Issued at Foreign Service Posts Fiscal Years 2011–2015.”

60. Dara Lind, “The Art of Denial,” Vox, March 31, 2017, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/3/31/14985324/visa-denial-why-trump-change-vetting.

61. Kerry v. Din 576, US 15 (2015).

62. These quotas exclude immediate family members. United States Department of State, “Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-Sponsored and Employment-Based preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2015,” https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/Immigrant-Statistics/WaitingList/WaitingListItem_2017.pdf

63. Security, “2015 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics,” table 34.

64. Michael D. Shear and Adam Liptak, “Supreme Court Takes Up Travel Ban, and Allows Parts to Go Ahead,” New York Times, June 26, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/26/us/politics/supreme-court-trump-travel-ban-case.html?_r=0.