Hunting for Sailors

Restaurant Raids and Conscription of Laborers during World War II

On January 9, 1943, five squads of US government agents ripped through New York’s Chinese community in the middle of the night. Seventy-four sailors from China had recently abandoned the Empress of Scotland, a British naval auxiliary ship, midway through their shipping contracts. To intimidate all Chinese for these men’s insubordination, English diplomats called upon the United States government, a wartime ally, for help. Using UK intelligence, fifteen US immigration agents, two translators, and six police detectives stormed places where Chinese mariners commonly gathered. American officials interrogated fifteen hundred Chinese at restaurants, boardinghouses, association headquarters, clubs, poolrooms, and theaters. The raid failed to recover these men. On January 11, the Empress navigated the Long Island Sound toward the Atlantic with one returnee and four recruits.1 British officials claimed success despite the paltry results. The incident, it turned out, gave England pretense to scare Chinese merchant mariners into obedience. An Englishman who helped hunt for sailors from the Empress enjoyed “leaving the bewildered inhabitants of Chinatown with a vest-pocket notion of what the original Sack of Rome was like.”2

British statesmen justified these tactics as wartime expediencies. English ships shuttled the lion’s share of fuel, food, ammunition, and machinery for the European front across the Atlantic via New York. These private transporters depended on Chinese sailors, far cheaper than unionized Englishmen, for brute manpower. Approximately ten thousand Chinese nationals worked on English ships during World War II. British liners contracted them in East Asian colonies for the lowest-paid and most strenuous tasks. Chinese seamen appealed for better conditions and, when negotiations collapsed, deserted in protest at the port of New York. Instead of granting parity in contract, England sought support from America for coerced service. Agreeing to an extreme approach, the US War Shipping Administration (WSA) and Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) designed the Alien Seamen Program with English interests in mind. The program tasked the INS with tracking and finding mariners who sought better employment on US soil. Captured seamen had the option of reshipping with previous employers or deportation to their home countries. Still, Chinese seamen refused British assignments, and Japan’s wartime control of the Chinese coast forced the INS to hold Chinese deserters indefinitely. In the words of New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, “Internment is paradise to the hell that they have gone through.”3 The Crown, resourceful and desperate, pursued draconian punishments. The British Ministry of War Transportation pushed legislative amendments to US immigration law to deport Chinese to British territories. Under these wartime agreements, England wielded exceptional state power over Chinese nationals within the United States.

England could not will the Chinese into compliance. Chinese sailors benefited from kin networks in New York that helped them disappear and find employment ashore. The earliest Chinese settlers arrived on trading ships in the mid-nineteenth century and parlayed their experiences at sea into viable businesses on land. By the early twentieth century, many mariners-turned-entrepreneurs operated Chinese restaurants or employment brokerages specializing in food service. Former seamen found less-strenuous and better-paying jobs as waiters and cooks. During World War II, when trans-Atlantic assignments risked life and limb and English companies refused adequate compensation, Chinese mariners called upon ex-sailors for assistance. Their supporters built coalitions with local Chinese associations, Chinese diplomats in the United States, the American Civil Liberties Union, and US Seamen’s unions for equal benefits to white seamen. The flash point was shore leave, as we shall see. In the ensuing controversy the Ministry of War Transport relented to shore leave to great regret. Many ships lost a third of their kitchen and engine staffs, who preferred working in restaurants and hotels.4 Captains tightened controls in response, granting a few dozen Chinese leave at a time and refused to issue more until everyone returned. But the damage was done. Once granted, the British could not rescind shore leave without compromising their political position with China and the United States.

During World War II an unexpected game of cat and mouse unfolded in New York’s Chinatown. England played cat, Chinese sailors the elusive prey. In an aggressive and fearsome chase, the Crown expanded its reach through the US government, which lent its immigration apparatus to disciplining low-wage Chinese laborers. This history twists the established narrative of US immigration policy, which emphasizes the synergies between national labor and immigration agendas. The struggle of Chinese seamen against English shipping companies on American terra provides a triangulated framing. State power swelled and national borders hardened through the elaboration of immigration law and bureaucracy during the twentieth century. US federal officials used its muscles to serve foreign policy agendas, amending its laws to resolve the labor conflicts of an allied nation at the expense of laborers from another wartime partner. The INS and WSA walked eyes-wide-open into this arrangement despite warnings from legal experts in the Department of Justice against the political, legal, and ethical quandary. The Chinese seamen’s response to Anglo-US collaboration was equally global, involving coordinated protests in port cities around the globe. This article emphasizes the contradiction of an authority, predicated on national sovereignty. It served multiple national agendas yet was ineffectual at disciplining a transnational migrant network.

A Wartime Labor Crisis

At the start of armed conflict, British shipping companies took a hardline approach against the Chinese. Captains of English liners expected their Chinese crews would disappear in New York if allowed the opportunity. Taking preventive measures, they detained the Chinese onboard under armed guard, paid wages in British pounds instead of US dollars, and held vital personal documents, like passports and sailor’s books. English shipmasters developed these tactics to avoid hefty fines from the Immigration Bureau for runaway sailors. In 1924, US Congressmen raised the penalty from $500 to $1,000 per disappearance, which captains used to justify denying shore leave to the Chinese in New York during World War II. The number of alien sailors detained in US ports skyrocketed, from fewer than one thousand on the eve of war in Europe to more than fourteen thousand three years later. The number of Chinese detainees cannot be disaggregated because the INS lumped together all alien nationals in these figures. Their detentions likely increased disproportionately over this period. In correspondences with US immigration officials, the British insisted on confinement, regardless of how long or under what conditions the Chinese worked at sea. J. F. Delany, INS District Director of Baltimore, worked directly with British diplomats and captains on retention strategies. Delany reported to his superior that English officials blocked all efforts to extend shore leave to the Chinese because of Baltimore’s proximity to New York.5

Effective in the short term but detrimental to British interests in the long run, these sorts of measures eroded any residual willingness among the Chinese to serve. For years, Chinese seamen agitated for improvements with little success. Captains typically paid the Chinese a fraction of salaries paid to whites for the same duties. In 1939, able-bodied Anglo seamen earned £9.6 per month and Chinese seamen of the same rating earned £2.8 per month. The following year, the gap widened when the Ministry of War Transportation granted £5 war-risk bonuses to white sailors. Outraged Chinese sailors in Liverpool demanded the same benefits. The Ministry of War Transport countered with £2. Street demonstrations continued through early 1941, when Liverpool police started jailing protestors and deporting them to China. With central agitators swept out of the picture, the Chinese ambassador stepped in, reaching an agreement with his British counterpart after long and tense negotiations in April 1942. Shipping companies ignored the concessions, though. Many Chinese sailors never saw war-risk bonuses, back pay, or, in case of death, payment to next of kin.6 New York attorney Nathan Shapiro helped them sue for compensation and witnessed repeatedly England’s blatant disregard of legal commitments. Like his clients, he experienced an utter loss of faith, “[The] British Government has done little or nothing since April, 1942 in its negotiations for an agreement with the Chinese government for the improvement of the status of Chinese seamen.”7

After more than a month of false promises, April 1942 was a turning point for Chinese mariners circling the globe under the Union Jack. They could not be quieted after a British shipmaster slayed a Chinese seaman. On April 11, 1942, eleven Chinese sailors approached Captain Rowe for leave and back pay. Their vessel, the SS Silver Ash, berthed in Brooklyn Pier six weeks earlier. Rowe refused, and the disgruntled sailors turned violent. In the scuffle Rowe shot Lin Young Tsai dead. Two weeks later, a grand jury in New York dismissed charges against Rowe, finding his actions justified in the face of armed rebellion. The Chinese allegedly advanced with weapons to his cabin. Hearing shots, white crewmen arrived on scene to defend Captain Rowe. They overpowered and locked the Chinese below deck until New York police arrived. The Chinese sailors claimed a miscarriage of justice, arguing in a later suit that the court failed to properly take their witness statements. What they saw contradicted the court record, and no one spoke their dialect adequately for them to convey their side. In the end, Rowe served no time, while the ten surviving sailors faced charges of disorderly conduct. Lin’s family received no compensation for his death either.8 The outcome sparked global protests. Chinese sailors grounded ships in the British ports of Jamaica, Sri Lanka, and Mauritius. The colonial office of Kolkata, India dispatched a “strong force of police” to silence two thousand to three thousand Chinese marching in the streets. Chinese crews in New York coordinated their walk out with strikers in New Orleans, encouraging them to preserve in their “united” struggle.9

The controversy spiraled out of control, forcing English statesmen to concede on seamen’s rights. The Associated Press cabled news of Lin’s death on the evening wire; major newspapers across the country ran the story the next day.10 The rapid publicity brought labor unions and civil rights organizations on the side of the Chinese. Thomas Christensen and Joseph Curran of the National Maritime Union supported the Chinese at an international conference in June, while a Dutch mariner union established a Chinese branch out of solidarity. On June 23, Edward Ross, chairman and general counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), urged Attorney General Francis Biddle to permit shore leave. Sailors typically enjoyed time ashore while their vessels docked for trade and repair, but the British refused the Chinese that privilege. Ross persuaded Biddle to resolve the issue of race-based wage discrimination and mistreatment of a wartime ally with one policy change. He suggested releasing Chinese sailors on bonds secured through local organizations and with the cooperation of foreign diplomats.11 On the other side of this debate, British shippers argued that the Chinese would disappear on shore leave, but they relented under pressure from high-level diplomats. Consuls General Tsune Chi Yu and Godfrey Haggard ironed out details for a two-month trial on Chinese shore leave. The agreement required Chinese officials to compel crews of China’s commitment to England and for mariners to sign reshipping pledges. The plan rested on the dubious assumption that sailors would not allow China to lose face. On August 5, Consuls Yu and Haggard welcomed sixty-two Chinese arriving on a British freighter to New York.12

Chinese sailors used these freshly won rights to damage English shipping. British diplomats stipulated that they would retract shore-leave privileges if the Chinese refused to reship. Government officials called this act a “desertion,” even though merchant mariners worked as civilians on private shipping missions. The Chinese abandoned their assignments anyway. The United Kingdom lost twice as many sailors after the concession. From September through December 1942, 250 Chinese left sixteen British ships at US ports. Diplomatic historian Meredith Oyen notes that Chinese disappeared en masse, instead of one by one. Because captains relegated them to kitchens and engine rooms, these wholesale departures crippled entire departments and, consequently, grounded ships in port. Vessels traveled in armed convoys across the Atlantic as protection against U-boat attacks. Short-handed ships missed scheduled convoys. Chinese desertions vexed the Atlantic mission, delaying fifty-one Allied ships. The backlog removed five ships temporarily from transoceanic service.13 Once taken for granted as cheap, subservient laborers, Chinese sailors suddenly wielded outsized power. Oyen writes, “Chinese sailors unexpectedly put the success of the entire supply operation, and by extension the war, in jeopardy.” Because so much rested on Chinese willingness, England plied enormous resources to the problem. T. T. Scott directed the British Shipping Mission office in Washington, DC. “The amount of time I and others consume on this problem is amazing,” he complained to his superior in London. “I breathe, eat and sleep Chinese.”14

To evade England’s watchful eye, the Chinese counted on friends and family for help disappearing ashore. Since the mid-nineteenth century, Chinese mariners had been jumping ship in New York, establishing a robust community by World War II. Ex-seamen lived separately from other Chinese, forming their own associations and businesses. New York’s Chinese population at mid-century was small (fewer than twenty thousand) but fractured along regional lines. Most Chinese came from Taishan, a mountainous county lying southwest of Hong Kong. Sailors typically traced their roots to Dapeng, a peninsula west of the British colony. In the tight urban economy of New York’s Chinatown, regional groups helped only their own.15 According to a British intelligence report, the Tai Pun (Dapeng) Association operated branches in major seaports to help members find temporary employment. Kong Bo, for example, jumped ship in New York early in the war. He vigorously encouraged other Dapengese to follow his example. The British intercepted a letter in which he promised a relative working for Blue Funnel, a Liverpool based transport company, “hundreds of dollars a month.” “All you need is [to] come up to Tai Pun Benevolent Association,” he instructed, “there will be someone to lead you to my apartment.”16 The British reported that the Dapengese assisted anyone without question. The president of a Tai Pun Association in Hong Kong proudly invoked a family metaphor to describe their devotion: “Because we belong to one Dapeng family. We know each other.”17

The work that Kong Bo promised was likely at a Chinese restaurant. Twentieth-century Chinese mariners often traded their sailing uniforms for chefs’ garb. The restaurant industry expanded rapidly in New York, reaching 18,927 licensed businesses and several thousand informal eateries by 1920. Chinese restaurants occupied a narrow but persistent slice of New York’s food industry. According to Fong Wing Kee, a steward in the British merchant marines, ex-sailors secured work for a nominal finder’s commission. Taking a don’t-ask–don’t-tell approach, managers hired the Chinese without learning immigration statuses and shielded them from suspicious INS agents. Hotels and restaurants paid Chinese seamen $32 a week, which was double their earnings at sea. When INS agents went looking for deserters, they searched first in hotel and restaurant kitchens. For this reason, the hunt for Empress of Scotland deserters started at Chinese restaurants. District Director of New York W. F. Watkins “commenced a systematic search,” using information about native origins to identify three large restaurants in Manhattan and several minor operations in Jersey City.18

In the spirit of “one Dapeng family,” ex-seamen employed people from their native regions. Ho Ping, for example, was a resourceful and talented cook who started two restaurants within fifteen years of arriving in New York. In 1929 he opened his first restaurant with a distant cousin, who went by Jimmie Ho. Both men came to New York as mariners and learned the restaurant business through kinsmen. Taishanese men dominated New York’s food-service industry and would only hire Taishanese. The Hos established restaurants in Brooklyn to stake out a corner of New York as Dapengese territory. Five years after their first restaurant opened, the cousins recruited two new partners for a second eatery.19 Because they worked with and hired relatives, the Hos’ success enriched the Dapengese community and created alternative opportunities for maritime people.

As physical locations, Chinese restaurants doubled as addresses to look up help. Sailors who planned to jump ship carried the business cards of restaurants to sea. Before leaving Liverpool, Chung Wing Kee got You Gee’s contact information in Jacksonville, Florida. Chung decided to desert after nearly dying on assignment. Germans torpedoed his ship, and his British shipper granted him only three days’ rest. Finding the schedule inhumane, Chung contacted You Gee, who ran a Chinese restaurant in Jacksonville. Chung and four other sailors wanted to reach New York. Agreeing to smuggle them into the country, You Gee met the party at the dock, drove them to a hiding place and arranged train tickets. In another case, Lee Choy and Lee Joe rendezvoused at Tung Kee Restaurant in New York’s Chinatown. The restaurant provided a place for the men to plot and carry out escape. Lee Choy arrived on the British steamship Pyndarius on March 8, 1942, before the Chinese won shore leave. The captain permitted Lee Choy a few hours to shop in Chinatown under armed guard. Lee Joe was once a sailor and felt obligated to help the Dapengese escape. Lee Choy reached Lee Joe at Lin Fong restaurant, where he cooked; they agreed to meet. Lee Joe arrived with a pocket full of cash to bribe the guard. He offered $500 to let his friend walk free.20

Chinese restaurants dotted the eastern seaboard and provided a literal escape route leading to New York. Ho C. Lui organized a path from Jacksonville, Florida, to New York City using restaurants as safe houses. He was a food-service veteran and built an expansive network of industry colleagues along the Atlantic coast. Top Hat Restaurant in Fayetteville, North Carolina, Hing Far Law Restaurant in Washington, DC, and Golden Pheasant Restaurant in Philadelphia were just three locations in a thick address book, places where Ho hid runaway sailors. These businesses served as stopping points in what a US immigration official cheekily called the “underground railway for Chinese.” When aspiring deserters arrived in a US seaport, they took shelter at local Chinese restaurants, while Ho arranged the logistics via correspondence. He also helped the Chinese cover their paths. He instructed them in how to avoid detection by shipping companies and advised planting fake intelligence to throw investigators off their trail. Other Chinese designed similar, though simpler, operations.21

While the Chinese preferred safer jobs on land, restaurant work did not necessarily appeal to them more than maritime duties. Their chief complaint aimed at racism. British seamen treated them with open contempt, which the Chinese refused to tolerate anymore. After weeks at sea, the racial antagonism threatened to erupt in violence. An English engineer remarked that he “expected to slide down the ladder some night into the engine room with a knife blade between his shoulders.” The engineer attempted to explain conditions on the SS California Standard to an INS inspector. Twenty-nine of thirty-two Chinese crewmen left the engine room. The desertions made sense to the inspector. He observed Chinese and British sailors brimming with suspicion, anger, and resentment toward one another. From his survey of work relations, he gathered that English officers slept with “guns strapped on or within easy reach.” Nathan Shapiro, the New York lawyer, urged a simple solution: he promised that Chinese seamen would return if they were treated like British seamen instead of coolies.22 To the Chinese the wage differences reflected how little England valued them. The Chinese Nationalist Daily and China Daily News printed this open letter from a seaman to the Chinese Consul General in New York:

We left our families behind to serve on Allied ships because we wanted to do our share to gain final victory, but British and Dutch ships distinguish between the white race and the yellow and are prejudiced against us. … The object of arrest is apparently to force us to continue working like slave for low wages, with delayed salaries … by imprisonment … inhuman acts such as these do not differ from Axis dictatorial brutality.23

They protested for equal pay as evidence of changed attitudes. British captains agreed with the diagnosis: “It may be that the Chinese had for too long been regarded as a source of cheap labor.”24

The Chinese were not alone in their opinions. Sailors of all nationalities refused to sail with England because of problems on ship. Historians typically attribute the higher rates of desertion to the U-boat threat. With the United States joining the Allies in 1942, Hitler committed fully to the U-boat strategy, adding to his fleet thirty new submarines each month. Germans sank one million tons of Allied shipping in August and September 1942 alone.25 While fear of death certainly played a factor, deserters described English shippers as terrible employers. Thomas Christensen of the National Maritime Union surveyed alien seamen held by the INS. The Bureau caught and detained sailors who overstayed their shore leaves on Riker’s Island until they accepted new assignments. Christensen interviewed two-thirds of imprisoned sailors in search of causes and solutions to the desertion patterns, none of whom were Chinese. Their responses revealed a systemic problem with English companies. The interviewees said they would reship with any company but UK lines, with more than half preferring imprisonment. Life on Riker’s Island was no vacation either. Christensen observed intolerable conditions. Detainees slept directly on metal bedframes, received no medical treatment for routine and emergency conditions, and suffered malnourishment. Some interviewees lost forty pounds over three months. Many interviewees noted bitterly that German and Italian prisoners, enemy aliens of the state, and convicted criminals lived better than INS detainees. Still, they refused to work for the British.26

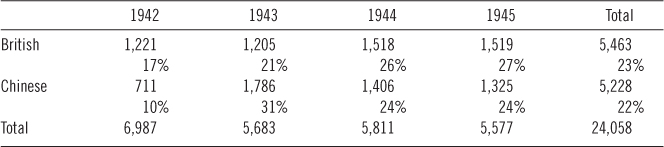

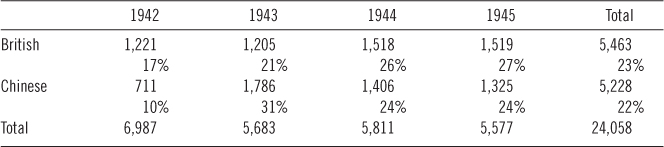

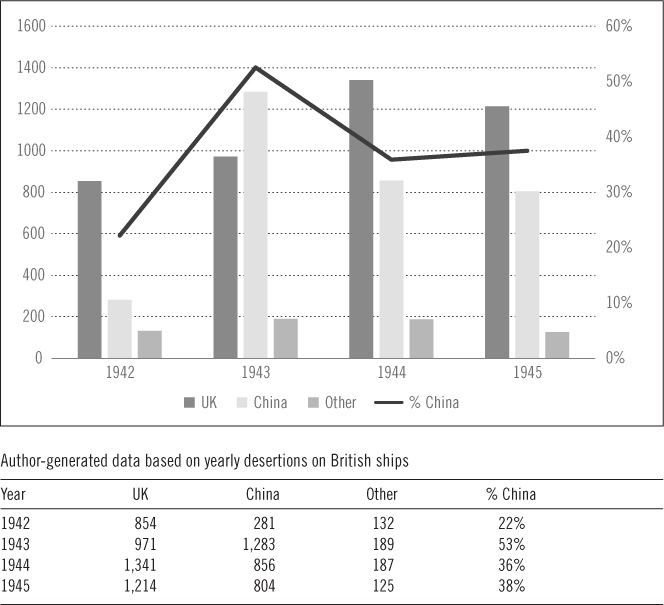

Consequently, sailors of every nationality left or refused missions from England. English sailors, in fact, held the dubious honor of leading the pack (see table 1). Desertion at US ports peaked in 1942, rising 50 percent over the previous year, from 4,661 to 6,987. Overall desertions fell below six thousand after June 1942, but British shipping continued to suffer. Desertions from England doubled the next year and averaged twenty-three hundred per year until the armistice. Between the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and German surrender in April 1945, 30 percent of desertions by foreign nationals in the United States left English ships (see figure 1).27 While British shipping suffered acutely from desertions, Chinese seamen do not deserve all the credit.

Faced with untenable labor unrest, England called upon allies to press mariners into service. Every detainee Christensen interviewed wanted a spot in the US merchant marines. American transporters paid the highest wages among Allied nations. In peacetime, sailors commonly found alternative employment during calls to port, which they colloquially called “floating.” The practice allowed seamen to negotiate between shippers for better wages. Arguing that floating harmed wartime shipping, the British orchestrated a pact with other Allied nations called the Alien Seamen Program. Signed in May 1942 by England, the United States, China, and several major shipping nations, the agreement allowed England to preserve its labor practices without losing to other shippers. It limited jobs on US ships to citizens of the United States or its territories and legally bound seamen to their last employer. The INS agreed to deport insubordinate seamen using an antiquated section of the 1917 Immigration Act, and created a new unit in each district office to handle seamen cases. New York, the highest-traffic port, dedicated ten special agents to inspect the crews of every incoming vessel, register arrivals by name, nationality, birthdate, and rating, and check for missing individuals when ships departed. The US government also footed the bill for finding and imprisoning deserters. In New York, where desertions were highest, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia gave part of county prisons on Riker’s Island to the program. English officials placed their bet on the intolerable conditions and threat of deportation to change opinions.28

Table 1. British and Chinese Desertions in the United States, 1942–1945

Source: Calculated from tables “Alien seamen deserted at American seaports, by nationality and flag of vessel and districts,” year ended June 30, 1942, 1943, 55854/370R, RG 85, Archive I; Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Washington, DC: GPO, 1944; 1945), 99; 7.

Figure 1. Desertions on British Ships by Nationality, 1942–1945

Source: Calculated from tables “Alien seamen deserted at American seaports, by nationality and flag of vessel and districts,” year ended June 30, 1942, 1943, 55854/370R, RG 85, Archive 1; Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Washington, DC: GPO, 1944; 1945), 99; 7.

Britain essentially won license to reinstate indentured servitude at sea. Three bodies of laws regulated alien seamen’s right of contract in the United States: British maritime statues, international treaties, and US immigration laws. English law defined “floating” as a criminal offense. Sailors signed to British ships faced punishments of hard labor and wage deductions for breaking their contracts. An 1892 treaty with Great Britain obligated US immigration officials to find, arrest, and deport deserters to stand trial before their home authorities. In 1915 the US legislature passed the La Follette Seamen’s Act, which rescinded those statues and decriminalized desertion in the United States.29 Passed during World War I, the act generated concern among congressmen, who worried that sailors would desert, so they incorporated registration and inspection requirements in the 1917 Immigration Act, along with a deportation provision for overstaying shore leave. The Alien Seamen Program resurrected the deportation clause, defining that refusing employment in wartime constituted a violation of US immigration law. The program forced sailors employed by England during World War II to accept British shipping conditions once again, which were utterly dismal.

US and British officials understood the Alien Seaman Program to target the Chinese above other nationalities. Edward J. Shaughnessy, the special assistant to the Commissioner General of Immigration, admitted that England sought cheap labor in the Chinese. “[It] is a well-known fact,” he wrote, “that because of the very low rate of wages paid to Chinese seamen, foreign steamship companies would probably be hesitant in discontinuing their employment.”30 Not everyone at the INS agreed with the course of action. Edward J. Ennis moved through the ranks as general counsel at the Justice Department to become director of the Alien Enemy Control Unit. He expressed reservations to the British positions, calling it “bad even for the war effort to use the power of this Government to sustain the substandard conditions on British naval auxiliaries for Chinese seamen by such a new regulation.” Agreeing with Ennis, Jack Wasserman produced an elaborate report characterizing US immigration law as the “whipping post for foreign government.” Wasserman served on the Board of Immigration Appeals, which made deportation rulings. His time administering the Alien Seamen Program embittered him. He concluded, “It is one thing to cooperate with foreign governments in furtherance of the war effort” but “quite another to cater to foreign self-interest that interferes with our own best interests.”31 For Ennis and Wasserman, carrying out the Alien Seaman Program on England’s behalf betrayed China and threatened US postwar politics in East Asia. They stood in the minority.

Still not satisfied, England cut a path through American immigration law to punish Chinese further. By early 1942, Japan controlled China’s coast, rendering a major component of the Alien Seamen Program unenforceable in Chinese cases. British diplomats disingenuously cried foul. T. T. Scott directed the British Shipping Mission office in Washington, DC. He complained vociferously to US counterparts, “It is just maddening to think that we must put all this extra work on our fine seamen so that John Chinaman can make his contribution to the war effort by washing dishes or underwear in Chinatown.”32 Scott and other members of the British embassy persuaded the WSA and INS to make Chinese deportations possible. Marshall Dimock, director of the War Shipping Administration, supported changing US immigration laws. Dimock testified before the Senate Committee on Immigration and Naturalization of the favoritism that present circumstances bestowed to the Chinese. “There is no reason in justice or diplomacy” to excuse the Chinese, as “[our] very survival makes it imperative that any and all seamen who desert their post of duty should be deportable.”33 The British wanted all seamen deported to Liverpool, where they would join standing labor pools for reshipment. A US court denied the option, declaring deporting the Chinese to the United Kingdom illegal. The final bill allowed deportation to India for conscription into the Chinese army.34

As the bill neared President Roosevelt’s desk, Scott giddily wrote his superior officer in London, “We shall have secured the biggest concession over the Chinese problem we could hope for.” He dedicated himself to seeing the law fully implemented. Demanding the INS “put ginger into their activities,” he asked for a “constant trickle of Chinese deportees.” Scott predicted that the Chinese would soon learn to fear England, “Every time a few Chinese are whisked away the news spread around Chinatown and among the other detainees on Ellis Island and the Chinese will begin to think … that the Americans [and British] really mean business.”35 The British shipping lines concocted wild theories so US officials would scrutinize the Chinese. Playing on fears of Axis infiltration, a captain for the Anglo-Saxon shipping company alleged that German spies organized Chinese seamen protests. The spies spoke fluent Chinese and socialized with Chinese seamen in New York’s Chinatown.36 The prodding worked. US officials pursued Chinese seamen disproportionately to other nationalities. The INS arrested nearly three thousand Chinese through the Alien Seamen Program, but only two thousand British seamen, the worst offenders to the Allied shipping efforts.37

Scott also pursued strategic displays of British power. The INS carried out raids for Empress of Scotland deserters on Scott’s bidding. Scott chose them because they protested in Liverpool before the Empress set sail, which, in his eyes, called for a harsh lesson. Four hundred Chinese had clashed with city police officers in the streets.38 In New York the protest leaders resumed their demands, calling upon the Chinese to publicly denounce the British. Shipping lines maintained lists of agitators and asked Scott to deport them back to England. They were spreading subversive, anti-British ideas among the local Chinese population. Scott handed over these lists to the INS, insisting their capture would end their Chinese labor problems. On January 5, 1943, the eve of the Empress’s departure, INS seamen agents ransacked Chinese residences and businesses. The INS detained roughly fifty-five hundred Chinese over two sweeps.39 British terror did not end there. The Empress of Scotland returned to New York two months later, and Scott prepared for a second raid before it landed. For several days, undercover INS and police agents identified two hundred sites for a “thorough frisk” and gave license to “ransack other spots in the course of the raid.” The agents did not capture the deserters, but London was pleased that desertions slowed in New York after this grand display.40

Conclusion

What should strike historians of nations and empires is the British effort to carry colonial labor regimes into the nation-state era. Through the wartime seamen policies, the Allies made non-US merchant mariners prisoners of their employers and expanded the ability of nation-states to control laborers beyond their borders. The British, however, used imperial coercion over citizens of another nation. Chinese resisted the British attempt to interpolate them into colonial servitude. In The Trouble with Empire, Antoinette Burton flags dissent and disruption as constitutive of empire. Not only was labor agitation and rebellion routine rather than exceptional, the struggle to discipline and govern produced the colonial practices that sustained British power.41 British officials treated the Chinese as colonial subjects, but the Chinese succeeded at evading British control via extensive Chinese social networks. Meredith Oyen credits the Chinese government with actively defending the rights of Chinese sailors abroad in a role that would have been more effectively filled by international seamen unions, had there been solidarity across racial lines.42 Its efforts neither brought about parity with white sailors nor halted Chinese desertion, because Chinese officials in the United States and the United Kingdom worked at cross purposes.43 To be certain, Chinese sailors also lacked confidence in the Chinese government to resolve their conflict with the British. Instead they placed full trust in their kinsmen, who supported their struggle in every way possible. This broad and empathetic network allowed Chinese seamen to engage in sustained and effective protest throughout the war.

The story here, then, is not so much British imperial power in the making, but the ability of transnational communities to check that power. During World War II, when Chinese desertion reached a disturbing milestone, the British worked tirelessly to extend its rule of law into Chinese restaurants of New York with the aid of the US government. In this game of cat and mouse, however, Chinese seafarers were clever prey. They understood their value to the war effort and leveraged the empathy of New York’s Chinese community, Chinese statesmen posted in the East Coast, and the wider American public to correct longstanding British mistreatment of Chinese seamen. While they never gained economic parity with Anglo seamen or tempered the racism on British ships, they organized enough momentum to improve work conditions more than all previous efforts. Moreover, their social networks and businesses survived this episode of imperial incursion on land. At the far reaches of empire, Chinese restaurants were only temporarily under the will of the British Crown. This period of colonial control nevertheless reveals expansive migrant networks that existed to counter the unchecked tyranny of imperial power upon its subjects.

Notes

1. W. F. Watkins to Herman R. Landon, January 9 and 11, 1943; Edward J. Shaughnessy to Earl G. Harrison, January 6, 1943, 56084/639, RG 85, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (Archives 1).

2. P. C. Devine, Memorandum to M. Borer, March 31, 1943, MT 9/4370, National Archives of the United Kingdom (Archives 1).

3. La Guardia to Cordell Hull, January 18, 1843, folder Chinese Seamen, box 3410, Mayor La Guardia Papers, NYC Municipal Archives (LGA).

4. T. T. Scott to Edward Shaughnessy, February 29, 1944, 55854/370V (Archives 1).

5. J. F. Delaney to Edward J. Shaughnessy, December 31, 1942; January 4, 1943, 56084/639; “Alien seamen arrived and departed,” year ended June 30, 1939, 1942, 55854/370R (Archives 1); Anna Pegler-Gordon, “Shanghaied on the Streets of Hoboken: Chinese Exclusion and Maritime Regulation at Ellis Island,” Journal for Maritime Research 16, no. 2 (2014): 236–37; Meredith Leigh Oyen, “Fighting for Equality: Chinese Seamen in the Battle of the Atlantic, 1939–1945,” Diplomatic History 38, no. 3 (2014): 532–33; Arnold W. Knauth, “Alien Seamen’s Rights and the War,” American Journal of International Law 37, no. 1 (1943): 77, 79.

6. Tony Lane, The Merchant Seaman’s War (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1991), 15, 162–64.

7. Shapiro to Department of Justice, February 15, 1943, 56084/639 (Archives 1).

8. “Raw Deal Handed Chinese Seamen,” The Pilot, ca. 1943, 56084/639 (Archives 1); Harry Howard, “Chinese Seamen’s Flight Shows Exclusion Act Should Be Repealed,” reel 213, vol. 2460, Archives of the American Civil Liberties Union, Princeton University (ACLU); Lane, Merchant Seaman’s War, 167; People v. Rowe, 36 NYS 2d 980 (1942).

9. Adolph A. Berle to Fiorello La Guardia, January 21, 1943, folder Chinese Seamen; Minutes, J. Megson, May 4, 1942; Captain J. Milhench to Misters A. Holt & Co., April 4, 1942, CO 323/1818/21 (TNA); J. B., “Extract from Survey No. 45 of Activities of Germans, Italians and Japanese in India for the Week Ending December 26, 1942,” January 1, 1943, WO 208/410 (TNA); Lo Hoi to Lam Chap, May 5, 1942, 55854/370F (Archives 1); Nathan Shapiro to Herman Landon, Jan. 8, 1943, 56084/639 (Archives 1).

10. Atlanta Constitution; Baltimore Sun; Chicago Tribune; Los Angeles Times; Washington Post, April 12, 1942.

11. New York Tribune, May 10; June 14, 1942; Ross to Biddle, Jun 23, 1942, 55854/370F (Archives 1).

12. New York Times, August 5, 1942; Earl Harrison to District Director of Ellis Island, November 25, 1942, 56084/639 (Archives 1).

13. Calculated from tables “Alien Seamen deserted at American seaports, by nationality and flag of vessel and districts,” year ended June 30, 1942, 1943, 55854/370R (Archives 1); Lane, Seamen’s War, 167; Dimock’s Speech to the Senate Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, April 1, 1943, 55854/370P (Archives I); Oyen, “Fighting for Equality,” 526–27.

14. Scott to N. A. Guttery, April 3, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA).

15. John Kuo Wei Tchen, New York before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776–1882 (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 76–81; Philip A. Kuhn, Chinese among Others: Emigration in Modern Times (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2008), 107–14, 125–26; Gregor Benton and Edmund Terence Gomez, The Chinese in Britain, 1800-Present: Economy, Transnationalism, Identity (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 49–50; Li Minghuan, “We Need Two Worlds”: Chinese Immigrant Associations in a Western Society (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1999), 143–419; US Bureau of the Census, 1950, Population, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1952), 56.

16. “Former Chinese Seaman Planning for His Relative to Jump Ship in New York,” April 1943, 56084/639 (Archives 1).

17. Minghuan, “We Need Two Worlds,” 144.

18. Report of Police Commissioner Enright, February 25, 1918, 9, box 81, USFA, Hoover Institution, Stanford University; Interview of Fong Wing Kee, June 22, 1943; Interview of Captain Merser and Officer Riches, May 31, 1943; F. B. A. Rundall to N. A. Guttery, October 16, 1944, MT 9/4370 (TNA); Report of Inspector W. F. Schlaar, December 15, 1915, 53775/149A (Archives 1).

19. Interrogation of Ho Ping by Timothy J. Molloy, December 5, 1939, 172/74 (NARA NY); Report on Ho Sang by Timothy J. Molloy, December 12, 1939; Interrogation of Ho Sang by Timothy J. Molloy, December 12, 1939, 172/75, RG 85, National Archive and Records Administration, New York (NARA NY); W. F. Watkins to Herman R. Landon, January 11, 1943, 56084/639 (Archives 1).

20. Examination of Chung Wing Kee, June 10, 1943, 56151/316, Archives I; Examination of Lee Choy, March 19, 1942; Examination of Lee Joe, March 18, 1942, 173/813, NARA NY.

21. Special Report by Samuel Auerbach, April 23, 1942; Special Report by Louis Wienckowski, April 27, 1943; J. R. Espinosa to Edward J. Shaughnessy, December 15, 1943, 55854/370F (Archives 1).

22. Irving F. Wixon to Edward J. Shaughnessy, January 7, 1943 (Archives 1); Shapiro to O’Laughlin, January 25, 1943, 56084/639 (Archives 1 / TNA).

23. Anonymous, January 27, 1943, Memorandum: Grievances of Chinese Seamen Now in the United States, March 31, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA).

24. Interview of Captain Merser, June 6, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA).

25. Terry Hughes and John Costello, The Battle of the Atlantic (New York: Dial, 1977), 9, 224–26.

26. Christensen to La Guardia, October 15, 1942, folder Alien Seamen, box 3375 (LGA).

27. Calculated from tables “Alien Seamen deserted at American seaports, by nationality and flag of vessel and districts,” year ended June 30, 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943, 55854/370R (Archives 1); Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Washington, DC: GPO, 1944), 99; Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Washington, DC: GPO, 1945), 75.

28. Instruction No. 75: The Alien Seaman Program, June 29, 1942, 55854/370F (Archives 1); Circular 44: British and Other Allied Seamen in the United States, April 9, 1942, 55854/370I, Archives I; Silvester Pindyck, “The Allied Seamen Program at New York,” INS Monthly Review 2, no. 1 (July 1944): 3–6. Marshall Dimock to Fiorello H. La Guardia, August 2, 1942; Lemuel B. Schofield to Fiorello H. La Guardia, April 2, 1942, folder Alien Seamen.

29. Conrad Hepworth Dixon, “Seamen and the Law: An Examination of the Impact of Legislation on the British Merchant Seaman’s Lot, 1588–1918” (PhD diss., University College London, 1981), 24–25, 207; Knauth, “Alien Seamen’s Rights.”

30. Edward J. Shaughnessy to Lemuel Schofield, July 8, 1942, 56084/639 (Archives 1).

31. Memorandum by Ennis, March 31, 1943, 55854/370P (Archives 1); Jack Wasserman, “Administration of the Alien Seaman Program,” ca. 1944, 55854/370R (Archives 1).

32. Scott to James F. O’Loughlin, April 23, 1943, 55854/370P (Archives 1).

33. Dimock’s Speech to the Senate Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, April 1, 1943, 55854/370P (Archives 1).

34. Minutes of Meeting between N. A. Guttery, Dr. Kuo, Mr. Dao, ca. January 1943; 78 Cong. Rec. H89,51 (daily ed. March 23, 1943) (statement of Reps. Schiffler, Marcantonio, and Michener); Lane, Merchant Seaman’s War, 156, 162–65.

35. Scott to Guttery, March 5, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA); “Alien Seamen Deserted from Vessels Arriving in American Seaports, for Year Ended June 30, 1942,” September 21, 1942, 55854/370R (Archives 1); “Alien Seamen Deserted from Vessels Arriving in American Seaports, for Year Ended June 30, 1943,” September 19, 1932, 55854/370R (Archives 1); T. T. Scott to Marshall Dimock, October 10, 1942; March 5, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA).

36. Interview with Captain van de Kooi, May 15, 1943; N. A. Guttery to J. R. Hobhouse, H. W. Rowbottom, and Richard Snedden, March 23, 1943; T. T. Scott to N. A. Guttery, March 5, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA).

37. Edward J. Shaughnessy to W. J. Zucker, February 6, 1946, 55854/370Z (Archives 1).

38. A. F. G. Ayling to W. C. Kneale, November 29, 1943; F. J. Hopwood to H. W. Rowbottom, August 30, 1944; T. T. Scott to Marshall Dimock, Mar. 5, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA); Lane, Merchant Seaman’s War, 165–67.

39. W. F. Watkins to Herman Landon, January 9 and 11, 1943; Edward J. Shaughnessy to Earl G. Harrison, January 6, 1943, 56084/639 (Archives 1).

40. W. F. Watkins to Herman Landon, January 11, 1943, 56084/639 (Archives 1); P. C. Devine, Memorandum to M. Borer, March 31, 1943; Note to W. C. Kneale, July 9, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA).

41. Antoinette Burton, The Trouble with Empire: Challenges to Modern British Imperialism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

42. Oyen, “Fighting for Equality.”

43. In negotiations, Chinese foreign minister T. V. Soong sided with the British, supporting deportation to India to punish deserters and requiring consuls in the United States to stand by a weak agreement he made with British on Chinese wages. N. A. Guttery to T. T. Scott, February 9, 1943; July 13, 1943; Minutes of Telephone Conversation between N. A. Guttery to Dr. Kuo, February 12, 1943; T. T. Scott to N. A. Guttery, March 5, 1943, MT 9/4370 (TNA); Viscount Halifax to Foreign Office, July 15, 1943, CAB 122/772 (TNA).